Fin (extended surface)

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

In the study of heat transfer, fins are surfaces that extend from an object to increase the rate of heat transfer to or from the environment by increasing convection. The amount of conduction, convection, or radiation of an object determines the amount of heat it transfers. Increasing the temperature gradient between the object and the environment, increasing the convection heat transfer coefficient, or increasing the surface area of the object increases the heat transfer. Sometimes it is not feasible or economical to change the first two options. Thus, adding a fin to an object, increases the surface area and can sometimes be an economical solution to heat transfer problems.

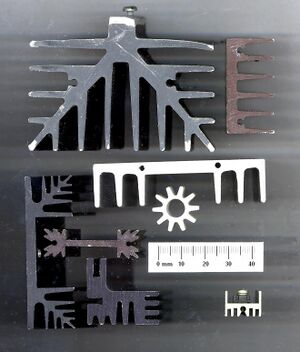

One-piece finned heat sinks are produced by extrusion, casting, skiving, or milling.

General case

To create a tractable equation for the heat transfer of a fin, many assumptions need to be made:

- Steady state

- Constant material properties (independent of temperature)

- No internal heat generation

- One-dimensional conduction

- Uniform cross-sectional area

- Uniform convection across the surface area

With these assumptions, conservation of energy can be used to create an energy balance for a differential cross section of the fin:[1]

Fourier’s law states that

where is the cross-sectional area of the differential element. Furthermore, the convective heat flux can be determined via the definition of the heat transfer coefficient h,

where is the temperature of the surroundings. The differential convective heat flux can then be determined from the perimeter of the fin cross-section P,

The equation of energy conservation can now be expressed in terms of temperature,

Rearranging this equation and using the definition of the derivative yields the following differential equation for temperature,

- ;

the derivative on the left can be expanded to the most general form of the fin equation,

The cross-sectional area, perimeter, and temperature can all be functions of x.

Uniform cross-sectional area

If the fin has a constant cross-section along its length, the area and perimeter are constant and the differential equation for temperature is greatly simplified to

where and . The constants and can now be found by applying the proper boundary conditions.

Solutions

The base of the fin is typically set to a constant reference temperature, . There are four commonly possible fin tip () conditions, however: the tip can be exposed to convective heat transfer, insulated, held at a constant temperature, or so far away from the base as to reach the ambient temperature.

For the first case, the second boundary condition is that there is free convection at the tip. Therefore,

which simplifies to

The two boundary conditions can now be combined to produce

This equation can be solved for the constants and to find the temperature distribution, which is in the table below.

A similar approach can be used to find the constants of integration for the remaining cases. For the second case, the tip is assumed to be insulated, or in other words to have a heat flux of zero. Therefore,

For the third case, the temperature at the tip is held constant. Therefore, the boundary condition is:

For the fourth and final case, the fin is assumed to be infinitely long. Therefore, the boundary condition is:

Finally, we can use the temperature distribution and Fourier's law at the base of the fin to determine the overall rate of heat transfer,

The results of the solution process are summarized in the table below.

| Case | Tip condition (x=L) | Temperature distribution | Fin heat transfer rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Convection heat transfer | ||

| B | Adiabatic | ||

| C | Constant Temperature | ||

| D | Infinite Fin Length |

Performance

Fin performance can be described in three different ways. The first is fin effectiveness. It is the ratio of the fin heat transfer rate () to the heat transfer rate of the object if it had no fin. The formula for this is:

where is the fin cross-sectional area at the base. Fin performance can also be characterized by fin efficiency. This is the ratio of the fin heat transfer rate to the heat transfer rate of the fin if the entire fin were at the base temperature,

in this equation is equal to the surface area of the fin. The fin efficiency will always be less than one, as assuming the temperature throughout the fin is at the base temperature would increase the heat transfer rate.

The third way fin performance can be described is with overall surface efficiency,

where is the total area and is the sum of the heat transfer from the unfinned base area and all of the fins. This is the efficiency for an array of fins.

-

Aluminium heat sink with low efficiency cooling fins

-

Aluminium heat sink with high efficiency cooling fins.

Inverted fins (cavities)

Open cavities are defined as the regions formed between adjacent fins and stand for the essential promoters of nucleate boiling or condensation. These cavities are usually utilized to extract heat from a variety of heat generating bodies. From 2004 until now, many researchers have been motivated to search for the optimal design of cavities.[2]

Uses

Fins are most commonly used in heat exchanging devices such as radiators in cars, computer CPU heatsinks, and heat exchangers in power plants.[3][4] They are also used in newer technology such as hydrogen fuel cells.[5] Nature has also taken advantage of the phenomena of fins. The ears of jackrabbits and fennec foxes act as fins to release heat from the blood that flows through them.[6]

References

- ↑ Lienhard, John H. IV; Lienhard, John H. V. (2019). A Heat Transfer Textbook (5th ed.). Mineola, NY: Dover Pub.. http://web.mit.edu/lienhard/www/ahtt.html.

- ↑ Lorenzini, G.; Biserni, C.; Rocha, L.A.O. (2011). "Geometric optimization of isothermal cavities according to Bejan's theory". International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 54 (17–18): 3868–3873. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2011.04.042.

- ↑ "Radiator Fin Machine or Machinery". FinTool International. http://www.fintool.com/. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ↑ "The Design of Chart Heat Exchangers". Chart. Archived from the original on 2006-10-11. https://web.archive.org/web/20061011191257/http://www.chart-ind.com/app_ec_he_design.cfm. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ "VII.H.4 Development of a Thermal and Water Management System for PEM Fuel Cells". Guillermo Pont. http://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/progress05/vii_h_4_pont.pdf. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ↑ Hill, R.; Veghte, J. (1976). "Jackrabbit ears: surface temperatures and vascular responses". Science 194 (4263): 436–438. doi:10.1126/science.982027. PMID 982027. Bibcode: 1976Sci...194..436H.

- Incropera, Frank; DeWitt, David P.; Bergman, Theodore L.; Lavine, Adrienne S. (2007). Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer (6 ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–168. ISBN 978-0-471-45728-2. https://archive.org/details/fundamentalsheat00incr_869.

|

KSF

KSF