Los Alamos Primer

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

The Los Alamos Primer is a printed version of the first five lectures on the principles of nuclear weapons given to new arrivals at the top-secret Los Alamos laboratory during the Manhattan Project. The five lectures were given by physicist Robert Serber in April 1943. The notes from the lectures which became the Primer were written by Edward Condon.

History

The Los Alamos Primer was composed from five lectures given by the physicist Robert Serber to the newcomers at the Los Alamos Laboratory in April 1943, at the start of the Manhattan Project. The aim of the project was to build the first nuclear bomb, and these lectures were a very concise introduction into the principles of nuclear weapon design. Serber was a postdoctoral student of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the leader of the Los Alamos Laboratory, and worked with him on the project from the very start. The five lectures were conducted at April 5, 7, 9, 12, and 14, 1943; according to Serber, between 30 and 50 people attended them. Notes were taken by Edward Condon; the Primer is just 24-pages-long. Only 36 copies were printed at the time.[1]

Serber later described the lectures:[1]

Previously the people working at the separate universities had no idea of the whole story. They only knew what part they were working on. So somebody had to give them the picture of what it was all about and what the bomb was like, what was known about the theory, and some idea why they needed the various experimental numbers.

In July 1942, Oppenheimer held a "conference" at his office at Berkeley. No records were preserved, but the Primer arose from all the aspects of bomb design discussed there.[1]

Content

The Primer, though only 24-pages-long, consists of 22 sections, divided into chapters:[1]

- Preliminaries

- Neutrons and the fission process

- Critical mass and efficiency

- Detonation, pre-detonation, and fizzles

- Conclusion

The first paragraph states the intention of the Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II:[1]

- The object of the project is to produce a practical military weapon in the form of a bomb in which the energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission.

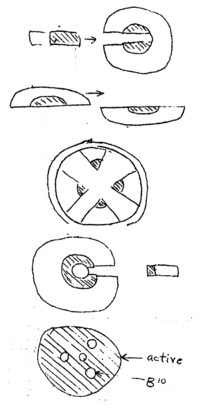

The Primer contained the basic physical principles of nuclear fission, as they were known at the time, and their implications for nuclear weapon design. It suggested a number of possible ways to assemble a critical mass of uranium-235 or plutonium, the most simple being the shooting of a "cylindrical plug" into a sphere of "active material" with a "tamper"—dense material which would reflect neutrons inward and keep the reacting mass together to increase its efficiency (this model, the Primer said, "avoids fancy shapes"). They also explored designs involving spheroids, a primitive form of "implosion" (suggested by Richard C. Tolman), and explored the speculative possibility of "autocatalytic methods" which would increase the efficiency of the bomb as it exploded.

According to Rhodes,

Serber discussed fission cross sections, the energy spectrum of secondary neutrons, the average number of secondary neutrons per fission (measured by then to be about 2.2), the neutron capture process in U238 that led to plutonium and why ordinary uranium is safe (it would have to be enriched to at least 7 percent U235, the young theoretician pointed out, 'to make an explosive reaction possible'). The calculations Serber reported indicated a critical mass of metallic U235 tamped with a thick shell of ordinary uranium of 15 kilograms: 33 pounds. For plutonium similarly tamped the critical mass might be 5 kilograms: 11 pounds. Tamper always increased efficiency: it reflected neutrons back into the core and its inertia...slowed the core's expansion and helped keep the core surface from blowing away. So there might be a third basic component to their atomic bomb besides nuclear core and confining tamper: an initiator - a Ra + Be source or, better, a Po + Be source, with the radium or polonium attached perhaps to one piece of the core and the beryllium to the other, to smash together and spray neutrons when the parts mated to start the chain reaction. The immediate work of experiment, Serber concluded, would be measuring the neutron properties of various materials and mastering the ordnance problem - the problem, that is, of assembling a critical mass and firing the bomb.[2]

The Primer became designated as the first official Los Alamos technical report (LA-1), and though its information about the physics of fission and weapon design was soon rendered obsolete, it is still considered a fundamental historical document in the history of nuclear weapons. Its contents would be of little use today to someone attempting to build a nuclear weapon, a fact acknowledged by its complete declassification in 1965.[3]

In 1992, an edited version of the Primer with many annotations and explanations by Serber was published with an introduction by Richard Rhodes, who previously published The Making of the Atomic Bomb. The 1992 edition also contains the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, written in 1940 in England.[3][4]

Reception

The physicist Freeman Dyson, who knew Serber, Oppenheimer, and other participants of the Manhattan Project, called the Primer a "legendary document in the literature of nuclear weapons". He praised "Serber's clear thinking", but harshly criticized the Primer's publication, writing "I still wish that it had been allowed to languish in obscurity for another century or two." Acknowledging that it was unclassified in 1965, and that it can't be useful to any bomb designer from 1950, Dyson still thinks that such publication can be dangerous:[3]

There is nothing here that would have been technically useful to a Russian bomb designer in 1950 or to an Iraqi bomb designer in 1990. But the primer contains much more than technical information. It conveys a powerful message that bomb designing is fun. The primer succeeds all too well in recreating the Los Alamos mystique, the picture of this brilliant group of city slickers suddenly dumped into the remotest corner of the Wild West and having the best time of their lives building bombs. It helps to perpetuate the myth. ... This is what I mean by seduction-the myth, unfortunately containing an element of truth, that building bombs is a wild, consciousness-raising adventure.

Dyson compared bomb-building with LSD synthesis: "Nuclear weapons and LSD are both highly addictive. Both have been manufactured extensively by bright young people seduced by a myth and searching for adventure. Both have destroyed many lives and are likely to destroy many more if the myths are not dispelled. ... Books that present either LSD or nuclear bombs as a romantic adventure can be a danger to public health and safety."[3]

His article, titled "Dragon's Teeth", reflects another analogy he uses in his criticisms:[3]

We are here confronting an ethical dilemma that is at least 350 years old, the same dilemma that John Milton confronted in his historic battle for the freedom of the press in 17th-century England. Milton in his famous appeal with the title "Areopagitica", addressed to the English parliament in 1644, conceded to his enemies the point that books "are as lively and as vigorously productive as those fabulous dragon's teeth, and being sown up and down, may chance to spring up armed men." He conceded that the risks of letting books go free into the world could be lethal as well as irreversible. He argued that the risks must still be accepted, because the censorship of books was the greater evil. He lost the argument, and in his day the censors prevailed. In our day, the censors have lost their grip, but the ethical dilemma remains. Books have not lost their power to spring up armed men, to seduce and to destroy. The fact that this primer was declassified 26 years ago does not mean that we can spread it over the world without some responsibility for the consequences.

Dyson concludes his review writing: "With luck, this charming little book will be read only by elderly l physicists and historians, people who can appreciate its elegance without being seduced by its ma"[3]

Other reviews, however, were more favorable. John F. Ahearne writes that the book "remains mathematical", and that it can be useful to young scientists: "the insight to be gained from reading Serber's lucid descriptions of how to analyze complex events by using first approximations. Serber was speaking in many cases to a group of experimentalists who, as one of the experimental group leaders is noted as saying, found "a qualitative argument was more convincing than any amount of fancy theory." A good physicist should be able to get an approximate answer to any complex question using what he or she carries around in the head, the well known "back of the envelope" calculation."[5]

Paul W. Henriksen praised the book, writing that "one will be even more impressed with the magnitude of the effort to build an atomic bomb to try to end World War II". He notes that the "annotated version is fascinating in several respects. It is a rare instance in which one of the contributors to a historical event has gone back and explained his work, its importance, and the mistakes that were made at the same time." He also notes that the book is "one of the few books to deal at all with the technical side of the bomb project."[6]

Matthew Hersch writes that the book has "power to amaze", and that "The Los Alamos Primer is a work bound to be read differently by different generations ... [it] is a rich text that peers into a moment of innovation that had global consequences."[7]

Frank A. Settle also finds the primer to be unique in style and context, and sees it as "a significant contribution to the technical and scientific history of this important period."[4]

Publication history

- Serber, Robert (1992). The Los Alamos primer: the first lectures on How to build an atomic bomb. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07576-5.

- Serber, Robert; Rhodes, Richard (2020). The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb, Updated with a New Introduction by Richard Rhodes (1 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-34417-4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvw1d5pf.

Literature

Articles

- "Revisiting The Los Alamos Primer". Physics Today 70 (9): 42–49. 1 September 2017. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3692.

- "A physicists guide to The Los Alamos Primer". Physica Scripta 91 (11): 113002. 1 November 2016. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/91/11/113002.

Editions

- The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb (Updated). University of California Press. 2020. ISBN 978-0-520-37433-1.

- The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb. University of California Press. 1992. ISBN 978-0-520-07576-4.

Original

- The Los Alamos Primer, 1943, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Los_Alamos_Primer.pdf, retrieved 1 January 2024

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Reed, B Cameron (12 October 2016). "A physicists guide to The Los Alamos Primer". Physica Scripta 91 (11): 113002. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/91/11/113002. ISSN 0031-8949. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0031-8949/91/11/113002. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. pp. 460–464. ISBN 9781451677614.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Dyson, Freeman J. (1992). "Dragon's Teeth". Science 256 (5055): 388–389. ISSN 0036-8075. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2877089. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Settle, Frank A. (1992). "Review of The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures On How to Build an Atomic Bomb.". The Journal of Military History 56 (4): 710–711. doi:10.2307/1986188. ISSN 0899-3718. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1986188. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ Ahearne, John F. (1993). "Review of The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build An Atomic Bomb". American Scientist 81 (1): 87–88. ISSN 0003-0996. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29774827. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ Henriksen, Paul W. (1993). "Review of The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb". Isis 84 (3): 607–608. ISSN 0021-1753. http://www.jstor.com/stable/235709. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ Hersch, Matthew (1 March 2021). "Robert Serber. The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb" (in en). Isis 112 (1): 209–210. doi:10.1086/713798. ISSN 0021-1753. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/713798. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

External links

- LANL (2023-07-19). "The Los Alamos Primer". https://discover.lanl.gov/publications/national-security-science/2023-summer/the-los-alamos-primer/.

|

KSF

KSF