Matter wave

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 28 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 28 min

| Part of a series on |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

| [math]\displaystyle{ i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} | \psi (t) \rangle = \hat{H} | \psi (t) \rangle }[/math] |

Matter waves are a central part of the theory of quantum mechanics, being half of wave–particle duality. All matter exhibits wave-like behavior. For example, a beam of electrons can be diffracted just like a beam of light or a water wave.

The concept that matter behaves like a wave was proposed by French physicist Louis de Broglie (/dəˈbrɔɪ/) in 1924, and so matter waves are also known as de Broglie waves.

The de Broglie wavelength is the wavelength, λ, associated with a particle with momentum p through the Planck constant, h: [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = \frac{h}{p}. }[/math]

Wave-like behavior of matter was first experimentally demonstrated by George Paget Thomson and Alexander Reid's transmission diffraction experiment,[1] and independently in the Davisson–Germer experiment,[2][3] both using electrons; and it has also been confirmed for other elementary particles, neutral atoms and molecules.

Introduction

Background

At the end of the 19th century, light was thought to consist of waves of electromagnetic fields which propagated according to Maxwell's equations, while matter was thought to consist of localized particles (see history of wave and particle duality). In 1900, this division was questioned when, investigating the theory of black-body radiation, Max Planck proposed that the thermal energy of oscillating atoms is divided into discrete portions, or quanta.[4] Extending Planck's investigation in several ways, including its connection with the photoelectric effect, Albert Einstein proposed in 1905 that light is also propagated and absorbed in quanta,[5]:87 now called photons. These quanta would have an energy given by the Planck–Einstein relation: [math]\displaystyle{ E = h\nu }[/math] and a momentum vector [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \left|\mathbf{p}\right| = p = \frac{E}{c} = \frac{h}{\lambda} , }[/math] where ν (lowercase Greek letter nu) and λ (lowercase Greek letter lambda) denote the frequency and wavelength of the light, c the speed of light, and h the Planck constant.[6] In the modern convention, frequency is symbolized by f as is done in the rest of this article. Einstein's postulate was verified experimentally[5]:89 by K. T. Compton and O. W. Richardson[7] and by A. L. Hughes[8] in 1912 then more carefully including a measurement of Planck's constant in 1916 by Robert Millikan[9]

De Broglie hypothesis

When I conceived the first basic ideas of wave mechanics in 1923–1924, I was guided by the aim to perform a real physical synthesis, valid for all particles, of the coexistence of the wave and of the corpuscular aspects that Einstein had introduced for photons in his theory of light quanta in 1905.—de Broglie[10]

De Broglie, in his 1924 PhD thesis,[11] proposed that just as light has both wave-like and particle-like properties, electrons also have wave-like properties. His thesis started from the hypothesis, "that to each portion of energy with a proper mass m0 one may associate a periodic phenomenon of the frequency ν0, such that one finds: hν0 = m0c2. The frequency ν0 is to be measured, of course, in the rest frame of the energy packet. This hypothesis is the basis of our theory."[12][11]:{{{1}}}[13][14][15][16] (This frequency is also known as Compton frequency.)

To find the wavelength equivalent to a moving body, de Broglie[5]:214 set the total energy from special relativity for that body equal to hν: [math]\displaystyle{ E = \frac{mc^2}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}} = h\nu }[/math]

(Modern physics no longer uses this form of the total energy; the energy–momentum relation has proven more useful.) De Broglie identified the velocity of the particle, v, with the wave group velocity in free space: [math]\displaystyle{ v_\text{g} \equiv \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial k} = \frac{d\nu}{d(1/\lambda)} }[/math]

(The modern definition of group velocity uses angular frequency ω and wave number k). By applying the differentials to the energy equation and identifying the relativistic momentum: [math]\displaystyle{ p = \frac{mv}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}} }[/math]

then integrating, de Broglie arrived as his formula for the relationship between the wavelength, λ, associated with an electron and the modulus of its momentum, p, through the Planck constant, h:[17] [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = \frac{h}{p}. }[/math]

This is a fundamental relation of the theory.—Louis de Broglie, 1929 Nobel Lecture[18]

Schrödinger's (matter) wave equation

Following up on de Broglie's ideas, physicist Peter Debye made an offhand comment that if particles behaved as waves, they should satisfy some sort of wave equation. Inspired by Debye's remark, Erwin Schrödinger decided to find a proper three-dimensional wave equation for the electron. He was guided by William Rowan Hamilton's analogy between mechanics and optics (see Hamilton's optico-mechanical analogy), encoded in the observation that the zero-wavelength limit of optics resembles a mechanical system – the trajectories of light rays become sharp tracks that obey Fermat's principle, an analog of the principle of least action.[19]

In 1926, Schrödinger published the wave equation that now bears his name[20] – the matter wave analogue of Maxwell's equations – and used it to derive the energy spectrum of hydrogen. Frequencies of solutions of the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation differ from de Broglie waves by the Compton frequency since the energy corresponding to the rest mass of a particle is not part of the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation. The Schrödinger equation describes the time evolution of a wavefunction, a function that assigns a complex number to each point in space. Schrödinger tried to interpret the modulus squared of the wavefunction as a charge density. This approach was, however, unsuccessful.[21][22][23] Max Born proposed that the modulus squared of the wavefunction is instead a probability density, a successful proposal now known as the Born rule.[21]

The following year, 1927, C. G. Darwin (grandson of the famous biologist) explored Schrödinger's equation in several idealized scenarios.[24] For an unbound electron in free space he worked out the propagation of the wave, assuming an initial Gaussian wave packet. Darwin showed that at time [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] later the position [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] of the packet traveling at velocity [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] would be [math]\displaystyle{ x_0 + vt \pm \sqrt{\sigma^2 + (ht/2\pi\sigma m)^2} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] is the uncertainty in the initial position. This position uncertainty creates uncertainty in velocity (the extra second term in the square root) consistent with Heisenberg's uncertainty relation The wave packet spreads out as show in the figure.

Experimental confirmation

Matter waves were first experimentally confirmed to occur in George Paget Thomson and Alexander Reid's diffraction experiment[1] and the Davisson–Germer experiment,[2][3] both for electrons.

The de Broglie hypothesis and the existence of matter waves has been confirmed for other elementary particles, neutral atoms and even molecules have been shown to be wave-like.[25]

The first electron wave interference patterns directly demonstrating wave–particle duality used electron biprisms[26][27] (essentially a wire placed in an electron microscope) and measured single electrons building up the diffraction pattern. Recently, a close copy of the famous double-slit experiment[28]:{{{1}}} using electrons through physical apertures gave the movie shown.[29]

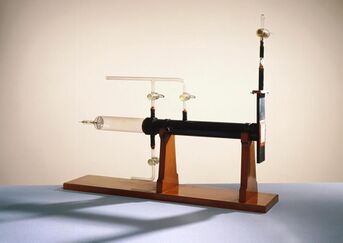

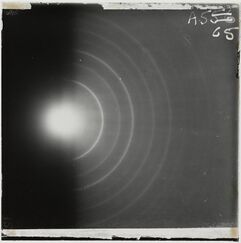

Electrons

In 1927 at Bell Labs, Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer fired slow-moving electrons at a crystalline nickel target.[2][3] The diffracted electron intensity was measured, and was determined to have a similar angular dependence to diffraction patterns predicted by Bragg for x-rays. At the same time George Paget Thomson and Alexander Reid at the University of Aberdeen were independently firing electrons at thin celluloid foils and later metal films, observing rings which can be similarly interpreted.[1] (Alexander Reid, who was Thomson's graduate student, performed the first experiments but he died soon after in a motorcycle accident[30] and is rarely mentioned.) Before the acceptance of the de Broglie hypothesis, diffraction was a property that was thought to be exhibited only by waves. Therefore, the presence of any diffraction effects by matter demonstrated the wave-like nature of matter.[31] The matter wave interpretation was placed onto a solid foundation in 1928 by Hans Bethe,[32] who solved the Schrödinger equation,[20] showing how this could explain the experimental results. His approach is similar to what is used in modern electron diffraction approaches.[33][34]

This was a pivotal result in the development of quantum mechanics. Just as the photoelectric effect demonstrated the particle nature of light, these experiments showed the wave nature of matter.

Neutrons

Neutrons, produced in nuclear reactors with kinetic energy of around 1 MeV, thermalize to around 0.025 eV as they scatter from light atoms. The resulting de Broglie wavelength (around 180 pm) matches interatomic spacing. In 1944, Ernest O. Wollan, with a background in X-ray scattering from his PhD work[35] under Arthur Compton, recognized the potential for applying thermal neutrons from the newly operational X-10 nuclear reactor to crystallography. Joined by Clifford G. Shull they developed[36] neutron diffraction throughout the 1940s. In the 1970s a neutron interferometer demonstrated the action of gravity in relation to wave–particle duality in a neutron interferometer.[37]

Atoms

Interference of atom matter waves was first observed by Immanuel Estermann and Otto Stern in 1930, when a Na beam was diffracted off a surface of NaCl.[38] The short de Broglie wavelength of atoms prevented progress for many years until two technological breakthroughs revived interest: microlithography allowing precise small devices and laser cooling allowing atoms to be slowed, increasing their de Broglie wavelength.[39]

Advances in laser cooling allowed cooling of neutral atoms down to nanokelvin temperatures. At these temperatures, the de Broglie wavelengths come into the micrometre range. Using Bragg diffraction of atoms and a Ramsey interferometry technique, the de Broglie wavelength of cold sodium atoms was explicitly measured and found to be consistent with the temperature measured by a different method.[40]

Molecules

Recent experiments confirm the relations for molecules and even macromolecules that otherwise might be supposed too large to undergo quantum mechanical effects. In 1999, a research team in Vienna demonstrated diffraction for molecules as large as fullerenes.[41] The researchers calculated a de Broglie wavelength of the most probable C60 velocity as 2.5 pm. More recent experiments prove the quantum nature of molecules made of 810 atoms and with a mass of 10123 Da.[42] As of 2019, this has been pushed to molecules of 25000 Da.[43]

In these experiments the build-up of such interference patterns could be recorded in real time and with single molecule sensitivity.[44] Large molecules are already so complex that they give experimental access to some aspects of the quantum-classical interface, i.e., to certain decoherence mechanisms.[45][46]

Traveling matter waves

Waves have more complicated concepts for velocity than solid objects. The simplest approach is to focus on the description in terms of plane matter waves for a free particle, that is a wave function described by [math]\displaystyle{ \psi (\mathbf{r}) = e^{ i \mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{r}-i \omega t }, }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r} }[/math] is a position in real space, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{k} }[/math] is the wave vector in units of inverse meters, ω is the angular frequency with units of inverse time and [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] is time. (Here the physics definition for the wave vector is used, which is [math]\displaystyle{ 2 \pi }[/math] times the wave vector used in crystallography, see wavevector.) The de Broglie equations relate the wavelength λ to the modulus of the momentum [math]\displaystyle{ |\mathbf{p}| = p }[/math], and frequency f to the total energy E of a free particle as written above:[47] [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \lambda = \frac {2 \pi}{|\mathbf{k}|} = \frac{h}{p}\\ & f = \frac{\omega}{2 \pi}= \frac{E}{h} \end{align} }[/math] where h is the Planck constant. The equations can also be written as [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \mathbf{p} = \hbar \mathbf{k}\\ & E = \hbar \omega ,\\ \end{align} }[/math] Here, ħ = h/2π is the reduced Planck constant. The second equation is also referred to as the Planck–Einstein relation.

Group velocity

In the de Broglie hypothesis, the velocity of a particle equals the group velocity of the matter wave.[5]:214 In isotropic media or a vacuum the group velocity of a wave is defined by: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v_g} = \frac{\partial \omega(\mathbf{k})}{\partial \mathbf{k}} }[/math] The relationship between the angular frequency and wavevector is called the dispersion relationship. For the non-relativistic case this is: [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(\mathbf{k}) \approx \frac{m_0 c^2}{\hbar} + \frac{\hbar k^2}{2m_{0} }\,. }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ m_0 }[/math] is the rest mass. Applying the derivative gives the (non-relativistic) matter wave group velocity: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v_g} = \frac{\hbar \mathbf{k}}{m_0} }[/math] For comparison, the group velocity of light, with a dispersion [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(k)=ck }[/math], is the speed of light [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math].

As an alternative, using the relativistic dispersion relationship for matter waves [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(\mathbf{k}) = \sqrt{k^2c^2 + \left(\frac{m_0c^2}{\hbar}\right)^2} \,. }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v_g} = \frac{\mathbf{k}c^2}{\omega} }[/math] This relativistic form relates to the phase velocity as discussed below.

For non-isotropic media we use the Energy–momentum form instead: [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{v}_\mathrm{g} &= \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial \mathbf{k}} = \frac{\partial (E/\hbar)}{\partial (\mathbf{p} /\hbar)} = \frac{\partial E}{\partial \mathbf{p}} = \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{p}} \left( \sqrt{p^2c^2+m_0^2c^4} \right)\\ &= \frac{\mathbf{p} c^2}{\sqrt{p^2c^2 + m_0^2c^4}}\\ &= \frac{\mathbf{p} c^2}{E} . \end{align} }[/math]

But (see below), since the phase velocity is [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}_\mathrm{p} = E/\mathbf{p} = c^2/\mathbf{v} }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \mathbf{v}_\mathrm{g} &= \frac{\mathbf{p}c^2}{E}\\ &= \frac{c^2}{\mathbf{v}_\mathrm{p}}\\ &= \mathbf{v} , \end{align} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] is the velocity of the center of mass of the particle, identical to the group velocity.

Phase velocity

The phase velocity in isotropic media is defined as: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v_p} = \frac{\omega}{\mathbf{k}} }[/math] Using the relativistic group velocity above:[5]:{{{1}}} [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v_p} = \frac{c^2 }{\mathbf{v_g}} }[/math] This shows that [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v_{p}}\cdot \mathbf{v_{g}}=c^2 }[/math] as reported by R.W. Ditchburn in 1948 and J. L. Synge in 1952. Electromagnetic waves also obey [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v_{p}}\cdot \mathbf{v_{g}}=c^2 }[/math], as both [math]\displaystyle{ |\mathbf{v_p}|=c }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ |\mathbf{v_g}|=c }[/math]. Since for matter waves, [math]\displaystyle{ |\mathbf{v_g}| \lt c }[/math], it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ |\mathbf{v_p}| \gt c }[/math], but only the group velocity carries information. The superluminal phase velocity therefore does not violate special relativity, as it does not carry information.

For non-isotropic media, then [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}_\mathrm{p} = \frac{\omega}{\mathbf{k}} = \frac{E/\hbar}{\mathbf{p}/\hbar} = \frac{E}{\mathbf{p}}. }[/math]

Using the relativistic relations for energy and momentum yields [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}_\mathrm{p} = \frac{E}{\mathbf{p}} = \frac{m c^2}{m \mathbf{v}} = \frac{\gamma m_0 c^2}{\gamma m_0 \mathbf{v}} = \frac{c^2}{\mathbf{v}}. }[/math] The variable [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] can either be interpreted as the speed of the particle or the group velocity of the corresponding matter wave—the two are the same. Since the particle speed [math]\displaystyle{ |\mathbf{v}| \lt c }[/math] for any particle that has nonzero mass (according to special relativity), the phase velocity of matter waves always exceeds c, i.e., [math]\displaystyle{ | \mathbf{v}_\mathrm{p} | \gt c , }[/math] which approaches c when the particle speed is relativistic. The superluminal phase velocity does not violate special relativity, similar to the case above for non-isotropic media. See the article on Dispersion (optics) for further details.

Special relativity

Using two formulas from special relativity, one for the relativistic mass energy and one for the relativistic momentum [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} E &= m c^2 = \gamma m_0 c^2 \\[1ex] \mathbf{p} &= m\mathbf{v} = \gamma m_0 \mathbf{v} \end{align} }[/math] allows the equations for de Broglie wavelength and frequency to be written as [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} &\lambda =\,\, \frac {h}{\gamma m_0v}\, =\, \frac {h}{m_0v}\,\,\, \sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}} \\[2.38ex] & f = \frac{\gamma\,m_0 c^2}{h} = \frac {m_0 c^2}{h\sqrt{1 - \frac{v^2}{c^2}}} , \end{align} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ v=|\mathbf{v}| }[/math] is the velocity, [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma }[/math] the Lorentz factor, and [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] the speed of light in vacuum.[48][49] This shows that as the velocity of a particle approaches zero (rest) the de Broglie wavelength approaches infinity.

Four-vectors

Using four-vectors, the de Broglie relations form a single equation: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{P}= \hbar\mathbf{K} , }[/math] which is frame-independent. Likewise, the relation between group/particle velocity and phase velocity is given in frame-independent form by: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{K} = \left(\frac{\omega_0}{c^2}\right)\mathbf{U} , }[/math] where

- Four-momentum [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{P} = \left(\frac{E}{c}, {\mathbf{p}} \right) }[/math]

- Four-wavevector [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{K} = \left(\frac{\omega}{c}, {\mathbf{k}} \right) }[/math]

- Four-velocity [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{U} = \gamma(c,{\mathbf{u}}) = \gamma(c,v_\mathrm{g} \hat{\mathbf{u}}) }[/math]

General matter waves

The preceding sections refer specifically to free particles for which the wavefunctions are plane waves. There are significant numbers of other matter waves, which can be broadly split into three classes: single-particle matter waves, collective matter waves and standing waves.

Single-particle matter waves

The more general description of matter waves corresponding to a single particle type (e.g. a single electron or neutron only) would have a form similar to [math]\displaystyle{ \psi (\mathbf{r}) = u(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{k})\exp(i\mathbf{k}\cdot \mathbf{r} - iE(\mathbf{k})t/\hbar) }[/math] where now there is an additional spatial term [math]\displaystyle{ u(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{k}) }[/math] in the front, and the energy has been written more generally as a function of the wave vector. The various terms given before still apply, although the energy is no longer always proportional to the wave vector squared. A common approach is to define an effective mass which in general is a tensor [math]\displaystyle{ m_{ij}^* }[/math] given by [math]\displaystyle{ {m_{ij}^*}^{-1} = \frac{1}{\hbar^2} \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial k_i \partial k_j} }[/math] so that in the simple case where all directions are the same the form is similar to that of a free wave above.[math]\displaystyle{ E(\mathbf k) = \frac{\hbar^2 \mathbf k^2}{2 m^*} }[/math]In general the group velocity would be replaced by the probability current[50] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{j}(\mathbf{r}) = \frac{\hbar}{2mi} \left( \psi^*(\mathbf{r}) \mathbf \nabla \psi(\mathbf{r}) - \psi(\mathbf{r}) \mathbf \nabla \psi^{*}(\mathbf{r}) \right) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \nabla }[/math] is the del or gradient operator. The momentum would then be described using the kinetic momentum operator,[50] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{p} = -i\hbar\nabla }[/math] The wavelength is still described as the inverse of the modulus of the wavevector, although measurement is more complex. There are many cases where this approach is used to describe single-particle matter waves:

- Bloch wave, which form the basis of much of band structure as described in Ashcroft and Mermin, and are also used to describe the diffraction of high-energy electrons by solids.[51][34]

- Waves with angular momentum such as electron vortex beams.[52]

- Evanescent waves, where the component of the wavevector in one direction is complex. These are common when matter waves are being reflected, particularly for grazing-incidence diffraction.

Collective matter waves

Other classes of matter waves involve more than one particle, so are called collective waves and are often quasiparticles. Many of these occur in solids – see Ashcroft and Mermin. Examples include:

- In solids, an electron quasiparticle is an electron where interactions with other electrons in the solid have been included. An electron quasiparticle has the same charge and spin as a "normal" (elementary particle) electron and, like a normal electron, it is a fermion. However, its effective mass can differ substantially from that of a normal electron.[53] Its electric field is also modified, as a result of electric field screening.

- A hole is a quasiparticle which can be thought of as a vacancy of an electron in a state; it is most commonly used in the context of empty states in the valence band of a semiconductor.[53] A hole has the opposite charge of an electron.

- A polaron is a quasiparticle where an electron interacts with the polarization of nearby atoms.

- An exciton is an electron and hole pair which are bound together.

- A Cooper pair is two electrons bound together so they behave as a single matter wave.

Standing matter waves

The third class are matter waves which have a wavevector, a wavelength and vary with time, but have a zero group velocity or probability flux. The simplest of these, similar to the notation above would be [math]\displaystyle{ \cos(\mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{r} - \omega t) }[/math] These occur as part of the particle in a box, and other cases such as in a ring. This can, and arguably should be, extended to many other cases. For instance, in early work de Broglie used the concept that an electron matter wave must be continuous in a ring to connect to the Bohr–Sommerfeld condition in the early approaches to quantum mechanics.[54] In that sense atomic orbitals around atoms, and also molecular orbitals are electron matter waves.[55][56][57]

Matter waves vs. electromagnetic waves (light)

Schrödinger applied Hamilton's optico-mechanical analogy to develop his wave mechanics for subatomic particles[58]:{{{1}}} Consequently wave solutions to Schrödinger's equation share many properties with results of light wave optics. In particular, Kirchhoff's diffraction formula works well for electron optics[28]:{{{1}}} and for atomic optics.[59] The approximation works well as long as the electric fields change more slowly than the de Broglie wavelength. Macroscopic apparatus fulfill this condition; slow electrons moving in solids do not.

Beyond the equations of motion, other aspects of matter wave optics differ from the corresponding light optics cases.

Sensitivity of matter waves to environmental condition. Many examples of electromagnetic (light) diffraction occur in air under many environmental conditions. Obviously visible light interacts weakly with air molecules. By contrast, strongly interacting particles like slow electrons and molecules require vacuum: the matter wave properties rapidly fade when they are exposed to even low pressures of gas.[60] With special apparatus, high velocity electrons can be used to study liquids and gases. Neutrons, an important exception, interact primarily by collisions with nuclei, and thus travel several hundred feet in air.[61]

Dispersion. Light waves of all frequencies travel at the same speed of light while matter wave velocity varies strongly with frequency. The relationship between frequency (proportional to energy) and wavenumber or velocity (proportional to momentum) is called a dispersion relation. Light waves in a vacuum have linear dispersion relation between frequency: [math]\displaystyle{ \omega = ck }[/math]. For matter waves the relation is non-linear: [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(k) \approx \frac{m_0 c^2}{\hbar} + \frac{\hbar k^2}{2m_{0} }\,. }[/math] This non-relativistic matter wave dispersion relation says the frequency in vacuum varies with wavenumber ([math]\displaystyle{ k=1/\lambda }[/math]) in two parts: a constant part due to the de Broglie frequency of the rest mass ([math]\displaystyle{ \hbar \omega_0 = m_{0}c^2 }[/math]) and a quadratic part due to kinetic energy. The quadratic term causes rapid spreading of wave packets of matter waves.

Coherence The visibility of diffraction features using an optical theory approach depends on the beam coherence,[28] which at the quantum level is equivalent to a density matrix approach.[62][63] As with light, transverse coherence (across the direction of propagation) can be increased by collimation. Electron optical systems use stabilized high voltage to give a narrow energy spread in combination with collimating (parallelizing) lenses and pointed filament sources to achieve good coherence.[64] Because light at all frequencies travels the same velocity, longitudinal and temporal coherence are linked; in matter waves these are independent. For example for atoms, velocity (energy) selection controls longitudinal coherence and pulsing or chopping controls temporal coherence.[59]:{{{1}}}

Optically shaped matter waves Optical manipulation of matter plays a critical role in matter wave optics: "Light waves can act as refractive, reflective, and absorptive structures for matter waves, just as glass interacts with light waves."[65] Laser light momentum transfer can cool matter particles and alter the internal excitation state of atoms.[66]

Multi-particle experiments While single-particle free-space optical and matter wave equations are identical, multiparticle systems like coincidence experiments are not.[67]

Applications of matter waves

The following subsections provide links to pages describing applications of matter waves as probes of materials or of fundamental quantum properties. In most cases these involve some method of producing travelling matter waves which initially have the simple form [math]\displaystyle{ \exp(i \mathbf{k}\cdot \mathbf{r} - i\omega t) }[/math], then using these to probe materials.

As shown in the table below, matter wave mass ranges over 6 orders of magnitude and energy over 9 orders but the wavelengths are all in the picometre range, comparable to atomic spacings. (Atomic diameters range from 62 to 520 pm, and the typical length of a carbon–carbon single bond is 154 pm.) Reaching longer wavelengths requires special techniques like laser cooling to reach lower energies; shorter wavelengths make diffraction effects more difficult to discern.[39] Therefore, many applications focus on material structures, in parallel with applications of electromagnetic waves, especially X-rays. Unlike light, matter wave particles may have mass, electric charge, magnetic moments, and internal structure, presenting new challenges and opportunities.

| matter | mass | kinetic energy | wavelength | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron | 1/1823 Da | 54 eV | 167 pm | Davisson–Germer experiment |

| Electron | 1/1823 Da | 5×104 eV | 5 pm | Tonomura et al. [68] |

| He atom, H2 molecule | 4 Da | 50 pm | Estermann and Stern[69] | |

| Neutron | 1 Da | 0.025 eV | 181 pm | Wollan and Shull[70] |

| Sodium atom | 23 Da | 20 pm | Moskowitz et al.[71] | |

| Helium | 4 Da | 0.065 eV | 56 pm | Grisenti et al.[72] |

| Na2 | 23 Da | 0.00017 eV | 459 pm | Chapman et al.[73] |

| C60 fullerene | 720 Da | 0.2 eV | 5 pm | Arndt et al.[41] |

| C70 fullerene | 841 Da | 0.2 eV | 2 pm | Brezger et al.[74] |

| polypeptide, Gramicidin A | 1860 Da | 360 fm | Shayeghi et al.[75] | |

| functionalized oligoporphyrins | 25000 Da | 17 eV | 53 fm | Fein et al.[76] |

Electrons

Electron diffraction patterns emerge when energetic electrons reflect or penetrate ordered solids; analysis of the patterns leads to models of the atomic arrangement in the solids.

They are used for imaging from the micron to atomic scale using electron microscopes, in transmission, using scanning, and for surfaces at low energies.

The measurements of the energy they lose in electron energy loss spectroscopy provides information about the chemistry and electronic structure of materials. Beams of electrons also lead to characteristic X-rays in energy dispersive spectroscopy which can produce information about chemical content at the nanoscale.

Quantum tunneling explains how electrons escape from metals in an electrostatic field at energies less than classical predictions allow: the matter wave penetrates of the work function barrier in the metal.

Scanning tunneling microscope leverages quantum tunneling to image the top atomic layer of solid surfaces.

Electron holography, the electron matter wave analog of optical holography, probes the electric and magnetic fields in thin films.

Neutrons

Neutron diffraction complements x-ray diffraction through the different scattering cross sections and sensitivity to magnetism.

Small-angle neutron scattering provides way to obtain structure of disordered systems that is sensitivity to light elements, isotopes and magnetic moments.

Neutron reflectometry is a neutron diffraction technique for measuring the structure of thin films.

Neutral atoms

Atom interferometers, similar to optical interferometers, measure the difference in phase between atomic matter waves along different paths.

Atom optics mimic many light optic devices, including mirrors, atom focusing zone plates.

Scanning helium microscopy uses He atom waves to image solid structures non-destructively.

Quantum reflection uses matter wave behavior to explain grazing angle atomic reflection, the basis of some atomic mirrors.

Quantum decoherence measurements rely on Rb atom wave interference.

Molecules

Quantum superposition revealed by interference of matter waves from large molecules probes the limits of wave–particle duality and quantum macroscopicity.[76][77]

Matter-wave interfererometers generate nanostructures on molecular beams that can be read with nanometer accuracy and therefore be used for highly sensitive force measurements, from which one can deduce a plethora or properties of individualized complex molecules.[78]

See also

- Bohr model

- Compton wavelength

- Faraday wave

- Kapitsa–Dirac effect

- Matter wave clock

- Schrödinger equation

- Theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation

- Thermal de Broglie wavelength

- De Broglie–Bohm theory

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Thomson, G. P.; Reid, A. (1927). "Diffraction of Cathode Rays by a Thin Film" (in en). Nature 119 (3007): 890. doi:10.1038/119890a0. ISSN 0028-0836. Bibcode: 1927Natur.119Q.890T.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Davisson, C.; Germer, L. H. (1927). "Diffraction of Electrons by a Crystal of Nickel". Physical Review 30 (6): 705–740. doi:10.1103/physrev.30.705. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1927PhRv...30..705D.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Davisson, C. J.; Germer, L. H. (1928). "Reflection of Electrons by a Crystal of Nickel" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 14 (4): 317–322. doi:10.1073/pnas.14.4.317. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 16587341. Bibcode: 1928PNAS...14..317D.

- ↑ Kragh, Helge (2000-12-01). "Max Planck: the reluctant revolutionary". https://physicsworld.com/a/max-planck-the-reluctant-revolutionary/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Whittaker, Sir Edmund (1989-01-01). A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity. 2. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26126-3.

- ↑ Einstein, A. (1917). Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung, Physicalische Zeitschrift 18: 121–128. Translated in ter Haar, D. (1967). The Old Quantum Theory. Pergamon Press. pp. 167–183. https://archive.org/details/oldquantumtheory00haar.

- ↑ Richardson, O. W.; Compton, Karl T. (1912-05-17). "The Photoelectric Effect". Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)) 35 (907): 783–784. doi:10.1126/science.35.907.783. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17792421. Bibcode: 1912Sci....35..783R. https://zenodo.org/record/1448080.

- ↑ Hughes, A. Ll. "XXXIII. The photo-electric effect of some compounds." The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 24.141 (1912): 380–390.

- ↑ Millikan, R. (1916). "A Direct Photoelectric Determination of Planck's "h"". Physical Review 7 (3): 355–388. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.7.355. Bibcode: 1916PhRv....7..355M.

- ↑ de Broglie, Louis (1970). "The reinterpretation of wave mechanics". Foundations of Physics 1 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1007/BF00708650. Bibcode: 1970FoPh....1....5D.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 de Broglie, Louis Victor. "On the Theory of Quanta". https://fondationlouisdebroglie.org/LDB-oeuvres/De_Broglie_Kracklauer.pdf.

- ↑ de Broglie, L. (1923). "Waves and quanta". Nature 112 (2815): 540. doi:10.1038/112540a0. Bibcode: 1923Natur.112..540D.

- ↑ Medicus, H.A. (1974). "Fifty years of matter waves". Physics Today 27 (2): 38–45. doi:10.1063/1.3128444. Bibcode: 1974PhT....27b..38M.

- ↑ MacKinnon, E. (1976). De Broglie's thesis: a critical retrospective, Am. J. Phys. 44: 1047–1055.

- ↑ Espinosa, J.M. (1982). "Physical properties of de Broglie's phase waves". Am. J. Phys. 50 (4): 357–362. doi:10.1119/1.12844. Bibcode: 1982AmJPh..50..357E.

- ↑ Brown, H.R.; Martins (1984). "De Broglie's relativistic phase waves and wave groups". Am. J. Phys. 52 (12): 1130–1140. doi:10.1119/1.13743. Bibcode: 1984AmJPh..52.1130B. http://repositorio.unicamp.br/jspui/handle/REPOSIP/79307. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ McEvoy, J. P.; Zarate, Oscar (2004). Introducing Quantum Theory. Totem Books. pp. 110–114. ISBN 978-1-84046-577-8.

- ↑ Louis de Broglie – Nobel Lecture. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2023. Fri. 2 Jun 2023. <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1929/broglie/lecture/>

- ↑ Schrödinger, E. (1984). Collected papers. Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn. ISBN 978-3-7001-0573-2. See the introduction to first 1926 paper.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Schrödinger, E. (1926). "An Undulatory Theory of the Mechanics of Atoms and Molecules" (in en). Physical Review 28 (6): 1049–1070. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.28.1049. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1926PhRv...28.1049S. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRev.28.1049.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Moore, W. J. (1992). Schrödinger: Life and Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-0-521-43767-7.

- ↑ Jammer, Max (1974). Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics: The interpretations of quantum mechanics in historical perspective. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-471-43958-5. https://archive.org/details/philosophyofquan0000jamm.

- ↑ Karam, Ricardo (June 2020). "Schrödinger's original struggles with a complex wave function" (in en). American Journal of Physics 88 (6): 433–438. doi:10.1119/10.0000852. ISSN 0002-9505. Bibcode: 2020AmJPh..88..433K. http://aapt.scitation.org/doi/10.1119/10.0000852.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles Galton. "Free motion in the wave mechanics." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 117.776 (1927): 258–293.

- ↑ Arndt, Markus; Hornberger, Klaus (April 2014). "Testing the limits of quantum mechanical superpositions" (in en). Nature Physics 10 (4): 271–277. doi:10.1038/nphys2863. ISSN 1745-2473. https://www.nature.com/articles/nphys2863.

- ↑ Merli, P. G., G. F. Missiroli, and G. Pozzi. "On the statistical aspect of electron interference phenomena." American Journal of Physics 44 (1976): 306

- ↑ Tonomura, A.; Endo, J.; Matsuda, T.; Kawasaki, T.; Ezawa, H. (1989). "Demonstration of single‐electron buildup of an interference pattern". American Journal of Physics (American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT)) 57 (2): 117–120. doi:10.1119/1.16104. ISSN 0002-9505. Bibcode: 1989AmJPh..57..117T.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Principles of Optics. Cambridge University Press. 1999. ISBN 978-0-521-64222-4.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Bach, Roger; Pope, Damian; Liou, Sy-Hwang; Batelaan, Herman (2013-03-13). "Controlled double-slit electron diffraction". New Journal of Physics (IOP Publishing) 15 (3): 033018. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/15/3/033018. ISSN 1367-2630. Bibcode: 2013NJPh...15c3018B. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1367-2630/15/3/033018.

- ↑ Navarro, Jaume (2010). "Electron diffraction chez Thomson: early responses to quantum physics in Britain" (in en). The British Journal for the History of Science 43 (2): 245–275. doi:10.1017/S0007087410000026. ISSN 0007-0874. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0007087410000026/type/journal_article.

- ↑ Mauro Dardo, Nobel Laureates and Twentieth-Century Physics, Cambridge University Press 2004, pp. 156–157

- ↑ Bethe, H. (1928). "Theorie der Beugung von Elektronen an Kristallen" (in de). Annalen der Physik 392 (17): 55–129. doi:10.1002/andp.19283921704. Bibcode: 1928AnP...392...55B. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/andp.19283921704.

- ↑ John M., Cowley (1995). Diffraction physics. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-82218-6. OCLC 247191522.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Peng, L.-M.; Dudarev, S. L.; Whelan, M. J. (2011). High energy electron diffraction and microscopy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960224-7. OCLC 656767858.

- ↑ Snell, A. H.; Wilkinson, M. K.; Koehler, W. C. (1984). "Ernest Omar Wollan". Physics Today 37 (11): 120. doi:10.1063/1.2915947. Bibcode: 1984PhT....37k.120S.

- ↑ Shull, C. G. (1997). "Early Development of Neutron Scattering". in Ekspong, G.. Nobel Lectures, Physics 1991–1995. World Scientific Publishing. pp. 145–154. https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1994/shull-lecture.pdf.

- ↑ Colella, R.; Overhauser, A. W.; Werner, S. A. (1975). "Observation of Gravitationally Induced Quantum Interference". Physical Review Letters 34 (23): 1472–1474. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.34.1472. Bibcode: 1975PhRvL..34.1472C. https://www.rpi.edu/dept/phys/Courses/PHYS6510/PhysRevLett.34.1472.pdf.

- ↑ Estermann, I.; Stern, Otto (1930). "Beugung von Molekularstrahlen". Z. Phys. 61 (1–2): 95. doi:10.1007/bf01340293. Bibcode: 1930ZPhy...61...95E.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Adams, C.S; Sigel, M; Mlynek, J (1994). "Atom optics". Physics Reports (Elsevier BV) 240 (3): 143–210. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(94)90066-3. ISSN 0370-1573. Bibcode: 1994PhR...240..143A.

- ↑ Pierre Cladé; Changhyun Ryu; Anand Ramanathan; Kristian Helmerson; William D. Phillips (2008). "Observation of a 2D Bose Gas: From thermal to quasi-condensate to superfluid". Physical Review Letters 102 (17): 170401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.170401. PMID 19518764. Bibcode: 2009PhRvL.102q0401C.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Arndt, M.; O. Nairz; J. Voss-Andreae; C. Keller; G. van der Zouw; A. Zeilinger (14 October 1999). "Wave–particle duality of C60". Nature 401 (6754): 680–682. doi:10.1038/44348. PMID 18494170. Bibcode: 1999Natur.401..680A.

- ↑ Eibenberger, Sandra; Gerlich, Stefan; Arndt, Markus; Mayor, Marcel; Tüxen, Jens (14 August 2013). "Matter–wave interference of particles selected from a molecular library with masses exceeding 10000 amu" (in en). Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 15 (35): 14696–700. doi:10.1039/c3cp51500a. ISSN 1463-9084. PMID 23900710. Bibcode: 2013PCCP...1514696E.

- ↑ "2000 atoms in two places at once: A new record in quantum superposition" (in en-us). https://phys.org/news/2019-09-atoms-quantum-superposition.html.

- ↑ Juffmann, Thomas (25 March 2012). "Real-time single-molecule imaging of quantum interference". Nature Nanotechnology 7 (5): 297–300. doi:10.1038/nnano.2012.34. PMID 22447163. Bibcode: 2012NatNa...7..297J.

- ↑ Hornberger, Klaus; Stefan Uttenthaler; Björn Brezger; Lucia Hackermüller; Markus Arndt; Anton Zeilinger (2003). "Observation of Collisional Decoherence in Interferometry". Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 (16): 160401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.160401. PMID 12731960. Bibcode: 2003PhRvL..90p0401H.

- ↑ Hackermüller, Lucia; Klaus Hornberger; Björn Brezger; Anton Zeilinger; Markus Arndt (2004). "Decoherence of matter waves by thermal emission of radiation". Nature 427 (6976): 711–714. doi:10.1038/nature02276. PMID 14973478. Bibcode: 2004Natur.427..711H.

- ↑ Resnick, R.; Eisberg, R. (1985). Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei and Particles (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-87373-0. https://archive.org/details/quantumphysicsof00eisb.

- ↑ Holden, Alan (1971). Stationary states. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-501497-6.

- ↑ Williams, W.S.C. (2002). Introducing Special Relativity, Taylor & Francis, London, ISBN:0-415-27761-2, p. 192.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Schiff, Leonard I. (1987). Quantum mechanics. International series in pure and applied physics (3. ed., 24. print ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-085643-1.

- ↑ Metherell, A. J. (1972). Electron Microscopy in Materials Science. Commission of the European Communities. pp. 397–552.

- ↑ Verbeeck, J.; Tian, H.; Schattschneider, P. (2010). "Production and application of electron vortex beams" (in en). Nature 467 (7313): 301–304. doi:10.1038/nature09366. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 20844532. Bibcode: 2010Natur.467..301V. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature09366.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Efthimios Kaxiras (9 January 2003). Atomic and Electronic Structure of Solids. Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–69. ISBN 978-0-521-52339-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=WTL_vgbWpHEC&pg=PA65.

- ↑ Jammer, Max (1989). The conceptual development of quantum mechanics. The history of modern physics (2nd ed.). Los Angeles (Calif.): Thomas publishers. ISBN 978-0-88318-617-6.

- ↑ Mulliken, Robert S. (1932). "Electronic Structures of Polyatomic Molecules and Valence. II. General Considerations". Physical Review 41 (1): 49–71. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.41.49. Bibcode: 1932PhRv...41...49M. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRev.41.49.

- ↑ Griffiths, David J. (1995). Introduction to quantum mechanics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-124405-4.

- ↑ Levine, Ira N. (2000). Quantum chemistry (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-685512-5.

- ↑ Schrödinger, Erwin (2001). Collected papers on wave mechanics: together with his Four lectures on wave mechanics (Third (augmented) edition, New York 1982 ed.). Providence, Rhode Island: AMS Chelsea Publishing, American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-3524-1.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Adams, C.S; Sigel, M; Mlynek, J (1994-05-01). "Atom optics" (in en). Physics Reports 240 (3): 143–210. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(94)90066-3. Bibcode: 1994PhR...240..143A.

- ↑ Schlosshauer, Maximilian (2019-10-01). "Quantum decoherence" (in en). Physics Reports 831: 1–57. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2019.10.001. Bibcode: 2019PhR...831....1S. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0370157319303084.

- ↑ Pynn, Roger (1990-07-01). "Neutron Scattering – A Primer". https://www.ncnr.nist.gov/summerschool/ss16/pdf/NeutronScatteringPrimer.pdf.

- ↑ Fano, U. (1957). "Description of States in Quantum Mechanics by Density Matrix and Operator Techniques" (in en). Reviews of Modern Physics 29 (1): 74–93. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.29.74. ISSN 0034-6861. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/RevModPhys.29.74.

- ↑ Hall, Brian C. (2013), "Systems and Subsystems, Multiple Particles" (in en), Quantum Theory for Mathematicians, Graduate Texts in Mathematics (New York, NY: Springer New York) 267: pp. 419–440, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7116-5_19, ISBN 978-1-4614-7115-8, https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4614-7116-5_19, retrieved 2023-08-13

- ↑ Hawkes, Peter W.; Hawkes, P. W. (1972). Electron optics and electron microscopy. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-85066-056-2.

- ↑ Cronin, Alexander D.; Schmiedmayer, Jörg; Pritchard, David E. (2009-07-28). "Optics and interferometry with atoms and molecules" (in en). Reviews of Modern Physics 81 (3): 1051–1129. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.81.1051. ISSN 0034-6861. Bibcode: 2009RvMP...81.1051C. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/52372.

- ↑ Akbari, Kamran; Di Giulio, Valerio; García De Abajo, F. Javier (2022). "Optical manipulation of matter waves". Science Advances 8 (42): eabq2659. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq2659. PMID 36260664. Bibcode: 2022SciA....8.2659A. https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/sciadv.abq2659.

- ↑ Brukner, Časlav; Zeilinger, Anton (1997-10-06). "Nonequivalence between Stationary Matter Wave Optics and Stationary Light Optics" (in en). Physical Review Letters 79 (14): 2599–2603. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.2599. ISSN 0031-9007. Bibcode: 1997PhRvL..79.2599B. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.2599.

- ↑ Tonomura, Akira; Endo, J.; Matsuda, T.; Kawasaki, T.; Ezawa, H. (1989). "Demonstration of single‐electron buildup of an interference pattern". American Journal of Physics 57 (2): 117–120. doi:10.1119/1.16104. Bibcode: 1989AmJPh..57..117T. https://pubs.aip.org/aapt/ajp/article-abstract/57/2/117/1040594/Demonstration-of-single-electron-buildup-of-an.

- ↑ Estermann, I.; Stern, O. (1930-01-01). "Beugung von Molekularstrahlen" (in de). Zeitschrift für Physik 61 (1): 95–125. doi:10.1007/BF01340293. ISSN 0044-3328. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01340293.

- ↑ Wollan, E. O.; Shull, C. G. (1948). "The Diffraction of Neutrons by Crystalline Powders". Physical Review (American Physical Society) 73 (8): 830–841. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.73.830. Bibcode: 1948PhRv...73..830W. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRev.73.830.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Philip E.; Gould, Phillip L.; Atlas, Susan R.; Pritchard, David E. (1983-08-01). "Diffraction of an Atomic Beam by Standing-Wave Radiation". Physical Review Letters 51 (5): 370–373. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.51.370. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.51.370.

- ↑ Grisenti, R. E.; W. Schöllkopf; J. P. Toennies; J. R. Manson; T. A. Savas; Henry I. Smith (2000). "He-atom diffraction from nanostructure transmission gratings: The role of imperfections". Physical Review A 61 (3): 033608. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.61.033608. Bibcode: 2000PhRvA..61c3608G.

- ↑ Chapman, Michael S.; Christopher R. Ekstrom; Troy D. Hammond; Richard A. Rubenstein; Jörg Schmiedmayer; Stefan Wehinger; David E. Pritchard (1995). "Optics and interferometry with Na2 molecules". Physical Review Letters 74 (24): 4783–4786. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.4783. PMID 10058598. Bibcode: 1995PhRvL..74.4783C.

- ↑ Brezger, B.; Hackermüller, L.; Uttenthaler, S.; Petschinka, J.; Arndt, M.; Zeilinger, A. (February 2002). "Matter–Wave Interferometer for Large Molecules" (reprint). Physical Review Letters 88 (10): 100404. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.100404. PMID 11909334. Bibcode: 2002PhRvL..88j0404B. http://homepage.univie.ac.at/Lucia.Hackermueller/unsereArtikel/Brezger2002a.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ↑ Shayeghi, A.; Rieser, P.; Richter, G.; Sezer, U.; Rodewald, J. H.; Geyer, P.; Martinez, T. J.; Arndt, M. (2020-03-19). "Matter-wave interference of a native polypeptide" (in en). Nature Communications 11 (1): 1447. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15280-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 32193414.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Fein, Yaakov Y.; Geyer, Philipp; Zwick, Patrick; Kiałka, Filip; Pedalino, Sebastian; Mayor, Marcel; Gerlich, Stefan; Arndt, Markus (December 2019). "Quantum superposition of molecules beyond 25 kDa" (in en). Nature Physics 15 (12): 1242–1245. doi:10.1038/s41567-019-0663-9. ISSN 1745-2481. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-019-0663-9.

- ↑ Nimmrichter, Stefan; Hornberger, Klaus (2013-04-18). "Macroscopicity of Mechanical Quantum Superposition States". Physical Review Letters 110 (16): 160403. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.160403. PMID 23679586. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.160403.

- ↑ Gerlich, Stefan; Fein, Yaakov Y.; Shayeghi, Armin; Köhler, Valentin; Mayor, Marcel; Arndt, Markus (2021), Friedrich, Bretislav; Schmidt-Böcking, Horst, eds., "Otto Stern's Legacy in Quantum Optics: Matter Waves and Deflectometry" (in en), Molecular Beams in Physics and Chemistry: From Otto Stern's Pioneering Exploits to Present-Day Feats (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 547–573, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-63963-1_24, ISBN 978-3-030-63963-1

Further reading

- L. de Broglie, Recherches sur la théorie des quanta (Researches on the quantum theory), Thesis (Paris), 1924; L. de Broglie, Ann. Phys. (Paris) 3, 22 (1925). English translation by A.F. Kracklauer.

- Broglie, Louis de, The wave nature of the electron Nobel Lecture, 12, 1929

- Tipler, Paul A. and Ralph A. Llewellyn (2003). Modern Physics. 4th ed. New York; W. H. Freeman and Co. ISBN:0-7167-4345-0. pp. 203–4, 222–3, 236.

- Zumdahl, Steven S. (2005). Chemical Principles (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-37206-5. https://archive.org/details/chemicalprincipl00zumd.

- An extensive review article "Optics and interferometry with atoms and molecules" appeared in July 2009: https://web.archive.org/web/20110719220930/http://www.atomwave.org/rmparticle/RMPLAO.pdf.

- "Scientific Papers Presented to Max Born on his retirement from the Tait Chair of Natural Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh", 1953 (Oliver and Boyd)

External links

- Bowley, Roger. "de Broglie Waves". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham. http://www.sixtysymbols.com/videos/debroglie.htm.

|

KSF

KSF