Perturbation theory

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

| Differential equations |

|---|

|

| Classification |

| Solution |

In mathematics and applied mathematics, perturbation theory comprises methods for finding an approximate solution to a problem, by starting from the exact solution of a related, simpler problem.[1][2] A critical feature of the technique is a middle step that breaks the problem into "solvable" and "perturbative" parts.[3] In perturbation theory, the solution is expressed as a power series in a small parameter .[1][2] The first term is the known solution to the solvable problem. Successive terms in the series at higher powers of usually become smaller. An approximate 'perturbation solution' is obtained by truncating the series, usually by keeping only the first two terms, the solution to the known problem and the 'first order' perturbation correction.

Perturbation theory is used in a wide range of fields, and reaches its most sophisticated and advanced forms in quantum field theory. Perturbation theory (quantum mechanics) describes the use of this method in quantum mechanics. The field in general remains actively and heavily researched across multiple disciplines.

Description

Perturbation theory develops an expression for the desired solution in terms of a formal power series known as a perturbation series in some "small" parameter, that quantifies the deviation from the exactly solvable problem. The leading term in this power series is the solution of the exactly solvable problem, while further terms describe the deviation in the solution, due to the deviation from the initial problem. Formally, we have for the approximation to the full solution a series in the small parameter (here called ε), like the following:

In this example, would be the known solution to the exactly solvable initial problem, and the terms represent the first-order, second-order, third-order, and higher-order terms, which may be found iteratively by a mechanistic but increasingly difficult procedure. For small these higher-order terms in the series generally (but not always) become successively smaller. An approximate "perturbative solution" is obtained by truncating the series, often by keeping only the first two terms, expressing the final solution as a sum of the initial (exact) solution and the "first-order" perturbative correction

Some authors use big O notation to indicate the order of the error in the approximate solution: [2]

If the power series in converges with a nonzero radius of convergence, the perturbation problem is called a regular perturbation problem.[1] In regular perturbation problems, the asymptotic solution smoothly approaches the exact solution.[1] However, the perturbation series can also diverge, and the truncated series can still be a good approximation to the true solution if it is truncated at a point at which its elements are minimum. This is called an asymptotic series. If the perturbation series is divergent or not a power series (for example, if the asymptotic expansion must include non-integer powers or negative powers ) then the perturbation problem is called a singular perturbation problem.[1] Many special techniques in perturbation theory have been developed to analyze singular perturbation problems.[1][2]

Prototypical example

The earliest use of what would now be called perturbation theory was to deal with the otherwise unsolvable mathematical problems of celestial mechanics: for example the orbit of the Moon, which moves noticeably differently from a simple Keplerian ellipse because of the competing gravitation of the Earth and the Sun.[4]

Perturbation methods start with a simplified form of the original problem, which is simple enough to be solved exactly. In celestial mechanics, this is usually a Keplerian ellipse. Under Newtonian gravity, an ellipse is exactly correct when there are only two gravitating bodies (say, the Earth and the Moon) but not quite correct when there are three or more objects (say, the Earth, Moon, Sun, and the rest of the Solar System) and not quite correct when the gravitational interaction is stated using formulations from general relativity.

Perturbative expansion

Keeping the above example in mind, one follows a general recipe to obtain the perturbation series. The perturbative expansion is created by adding successive corrections to the simplified problem. The corrections are obtained by forcing consistency between the unperturbed solution, and the equations describing the system in full. Write for this collection of equations; that is, let the symbol stand in for the problem to be solved. Quite often, these are differential equations, thus, the letter "D".

The process is generally mechanical, if laborious. One begins by writing the equations so that they split into two parts: some collection of equations which can be solved exactly, and some additional remaining part for some small . The solution (to ) is known, and one seeks the general solution to .

Next the approximation is inserted into . This results in an equation for , which, in the general case, can be written in closed form as a sum over integrals over . Thus, one has obtained the first-order correction and thus is a good approximation to . It is a good approximation, precisely because the parts that were ignored were of size . The process can then be repeated, to obtain corrections , and so on.

In practice, this process rapidly explodes into a profusion of terms, which become extremely hard to manage by hand. Isaac Newton is reported to have said, regarding the problem of the Moon's orbit, that "It causeth my head to ache."[5] This unmanageability has forced perturbation theory to develop into a high art of managing and writing out these higher order terms. One of the fundamental breakthroughs for controlling the expansion are the Feynman diagrams, which allow perturbation series to be written down diagrammatically.

Examples

Perturbation theory has been used in a large number of different settings in physics and applied mathematics. Examples of the "collection of equations" include algebraic equations,[6] differential equations (e.g., the equations of motion[7] and commonly wave equations), thermodynamic free energy in statistical mechanics, radiative transfer,[8] and Hamiltonian operators in quantum mechanics.

Examples of the kinds of solutions that are found perturbatively include the solution of the equation of motion (e.g., the trajectory of a particle), the statistical average of some physical quantity (e.g., average magnetization), the ground state energy of a quantum mechanical problem.

Examples of exactly solvable problems that can be used as starting points include linear equations, including linear equations of motion (harmonic oscillator, linear wave equation), statistical or quantum-mechanical systems of non-interacting particles (or in general, Hamiltonians or free energies containing only terms quadratic in all degrees of freedom).

Examples of systems that can be solved with perturbations include systems with nonlinear contributions to the equations of motion, interactions between particles, terms of higher powers in the Hamiltonian/free energy.

For physical problems involving interactions between particles, the terms of the perturbation series may be displayed (and manipulated) using Feynman diagrams.

History

Perturbation theory was first devised to solve otherwise intractable problems in the calculation of the motions of planets in the solar system. For instance, Newton's law of universal gravitation explained the gravitation between two astronomical bodies, but when a third body is added, the problem was, "How does each body pull on each?" Newton's equation only allowed the mass of two bodies to be analyzed. The gradually increasing accuracy of astronomical observations led to incremental demands in the accuracy of solutions to Newton's gravitational equations, which led several notable 18th and 19th century mathematicians, such as Lagrange and Laplace, to extend and generalize the methods of perturbation theory.

These well-developed perturbation methods were adopted and adapted to solve new problems arising during the development of quantum mechanics in 20th century atomic and subatomic physics. Paul Dirac developed quantum perturbation theory in 1927 to evaluate when a particle would be emitted in radioactive elements. This was later named Fermi's golden rule.[9][10] Perturbation theory in quantum mechanics is fairly accessible, as the quantum notation allows expressions to be written in fairly compact form, thus making them easier to comprehend. This resulted in an explosion of applications, ranging from the Zeeman effect to the hyperfine splitting in the hydrogen atom.

Despite the simpler notation, perturbation theory applied to quantum field theory still easily gets out of hand. Richard Feynman developed the celebrated Feynman diagrams by observing that many terms repeat in a regular fashion. These terms can be replaced by dots, lines, squiggles and similar marks, each standing for a term, a denominator, an integral, and so on; thus complex integrals can be written as simple diagrams, with absolutely no ambiguity as to what they mean. The one-to-one correspondence between the diagrams, and specific integrals is what gives them their power. Although originally developed for quantum field theory, it turns out the diagrammatic technique is broadly applicable to all perturbative series (although, perhaps, not always so useful).

In the second half of the 20th century, as chaos theory developed, it became clear that unperturbed systems were in general completely integrable systems, while the perturbed systems were not. This promptly lead to the study of "nearly integrable systems", of which the KAM torus is the canonical example. At the same time, it was also discovered that many (rather special) non-linear systems, which were previously approachable only through perturbation theory, are in fact completely integrable. This discovery was quite dramatic, as it allowed exact solutions to be given. This, in turn, helped clarify the meaning of the perturbative series, as one could now compare the results of the series to the exact solutions.

The improved understanding of dynamical systems coming from chaos theory helped shed light on what was termed the small denominator problem or small divisor problem. It was observed in the 19th century (by Poincaré, and perhaps earlier), that sometimes 2nd and higher order terms in the perturbative series have "small denominators". That is, they have the general form where , and are some complicated expressions pertinent to the problem to be solved, and and are real numbers; very often they are the energy of normal modes. The small divisor problem arises when the difference is small, causing the perturbative correction to blow up, becoming as large or maybe larger than the zeroth order term. This situation signals a breakdown of perturbation theory: it stops working at this point, and cannot be expanded or summed any further. In formal terms, the perturbative series is a asymptotic series: a useful approximation for a few terms, but ultimately inexact. The breakthrough from chaos theory was an explanation of why this happened: the small divisors occur whenever perturbation theory is applied to a chaotic system. The one signals the presence of the other.

Beginnings in the study of planetary motion

Since the planets are very remote from each other, and since their mass is small as compared to the mass of the Sun, the gravitational forces between the planets can be neglected, and the planetary motion is considered, to a first approximation, as taking place along Kepler's orbits, which are defined by the equations of the two-body problem, the two bodies being the planet and the Sun.[11]

Since astronomic data came to be known with much greater accuracy, it became necessary to consider how the motion of a planet around the Sun is affected by other planets. This was the origin of the three-body problem; thus, in studying the system Moon–Earth–Sun the mass ratio between the Moon and the Earth was chosen as the small parameter. Lagrange and Laplace were the first to advance the view that the constants which describe the motion of a planet around the Sun are "perturbed", as it were, by the motion of other planets and vary as a function of time; hence the name "perturbation theory".[11]

Perturbation theory was investigated by the classical scholars—Laplace, Poisson, Gauss—as a result of which the computations could be performed with a very high accuracy. The discovery of the planet Neptune in 1848 by Urbain Le Verrier, based on the deviations in motion of the planet Uranus (he sent the coordinates to Johann Gottfried Galle who successfully observed Neptune through his telescope), represented a triumph of perturbation theory.[11]

Perturbation orders

The standard exposition of perturbation theory is given in terms of the order to which the perturbation is carried out: first-order perturbation theory or second-order perturbation theory, and whether the perturbed states are degenerate, which requires singular perturbation. In the singular case extra care must be taken, and the theory is slightly more elaborate.

In chemistry

Many of the ab initio quantum chemistry methods use perturbation theory directly or are closely related methods. Implicit perturbation theory[12] works with the complete Hamiltonian from the very beginning and never specifies a perturbation operator as such. Møller–Plesset perturbation theory uses the difference between the Hartree–Fock Hamiltonian and the exact non-relativistic Hamiltonian as the perturbation. The zero-order energy is the sum of orbital energies. The first-order energy is the Hartree–Fock energy and electron correlation is included at second-order or higher. Calculations to second, third or fourth order are very common and the code is included in most ab initio quantum chemistry programs. A related but more accurate method is the coupled cluster method.

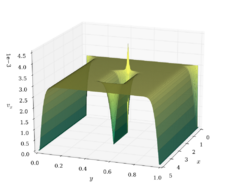

Shell-crossing

A shell-crossing (sc) occurs in perturbation theory when matter trajectories intersect, forming a singularity.[13] This limits the predictive power of physical simulations at small scales.

See also

- Boundary layer

- Cosmological perturbation theory

- Deformation (mathematics)

- Dynamic nuclear polarisation

- Eigenvalue perturbation

- Homotopy perturbation method

- Interval finite element

- Lyapunov stability

- Method of dominant balance

- Order of approximation

- Perturbation theory (quantum mechanics)

- Structural stability

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Bender, Carl M. (1999). Advanced mathematical methods for scientists and engineers I : asymptotic methods and perturbation theory. Steven A. Orszag. New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4757-3069-2. OCLC 851704808. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/851704808.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Holmes, Mark H. (2013). Introduction to perturbation methods (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-5477-9. OCLC 821883201. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/821883201.

- ↑ William E. Wiesel (2010). Modern Astrodynamics. Ohio: Aphelion Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-145378-1470.

- ↑ Martin C. Gutzwiller, "Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem", Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 589 – Published 1 April 1998

- ↑ Cropper, William H. (2004), Great Physicists: The Life and Times of Leading Physicists from Galileo to Hawking, Oxford University Press, p. 34, ISBN 978-0-19-517324-6.

- ↑ "L. A. Romero, "Perturbation theory for polynomials", Lecture Notes, University of New Mexico (2013)". http://math.unm.edu/~lromero/2013/class_notes/poly.pdf.

- ↑ Sergei Winitzki, "Perturbation theory for anharmonic oscillations", Lecture notes, LMU (2006)

- ↑ Michael A. Box, "Radiative perturbation theory: a review", Environmental Modelling & Software 17 (2002) 95–106

- ↑ Bransden, B. H.; Joachain, C. J. (1999). Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 443. ISBN 978-0582356917.

- ↑ Dirac, P.A.M. (1 March 1927). "The Quantum Theory of Emission and Absorption of Radiation". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 114 (767): 243–265. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0039. Bibcode: 1927RSPSA.114..243D. See equations (24) and (32).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Perturbation theory. N. N. Bogolyubov, jr. (originator), Encyclopedia of Mathematics. URL: http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Perturbation_theory&oldid=11676

- ↑ King, Matcha (1976). "Theory of the Chemical Bond". Journal of the American Chemical Society 98 (12): 3415–3420. doi:10.1021/ja00428a004.

- ↑ Rampf, Cornelius; Hahn, Oliver (2021-02-01). "Shell-crossing in a ΛCDM Universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 501: L71–L75. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slaa198. ISSN 0035-8711. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2021MNRAS.501L..71R.

External links

- van den Eijnden, Eric. "Introduction to regular perturbation theory". http://www.cims.nyu.edu/~eve2/reg_pert.pdf.

- Chow, Carson C. (23 October 2007). "Perturbation method of multiple scales". Scholarpedia 2 (10): 1617. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.1617.

- Alternative approach to quantum perturbation theory Martínez-Carranza, J.; Soto-Eguibar, F.; Moya-Cessa, H. (2012). "Alternative analysis to perturbation theory in quantum mechanics". The European Physical Journal D 66 (1): 22. doi:10.1140/epjd/e2011-20654-5. Bibcode: 2012EPJD...66...22M.

|

KSF

KSF