Premelting

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

Premelting (also surface melting) refers to a quasi-liquid film that can occur on the surface of a solid even below the bulk material's melting point (). The thickness of the film is temperature ()-dependent. This effect is common for all crystalline materials. Premelting shows its effects in frost heave, and, taking grain boundary interfaces into account, maybe even in the movement of glaciers.

Considering a solid-vapour interface, complete and incomplete premelting can be distinguished. During a temperature rise from below to above , in the case of complete premelting, the solid melts homogeneously from the outside to the inside; in the case of incomplete premelting, the liquid film stays very thin during the beginning of the melting process, but droplets start to form on the interface. In either case, the solid always melts from the outside inwards, never from the inside.

History

The first to mention premelting might have been Michael Faraday in 1842 for ice surfaces.[1] He compared the effect which holds a snowball together to that which makes buildings from moistured sand stable. Another interesting thing he mentioned is that two blocks of ice can freeze together. Later Tammann (1910) and Stranski (1942) suggested that all crystals might, due to the reduction of surface energy, start melting at their surfaces.[2][3] Frenkel strengthened this by noting that, in contrast to liquids, no overheating can be found for solids.[4] After extensive studies on many materials, it can be concluded that it is a common attribute of the solid state that the melting process begins at the surface.[5]

Theoretical explanations

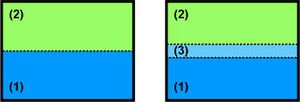

There are several ways to approach the topic of premelting, the most figurative way might be thermodynamically. A more detailed or abstract view on what physics is important for premelting is given by the Lifshitz and the Landau theories. One always starts with looking at a crystalline solid phase (fig. 1: (1) solid) and another phase. This second phase (fig. 1: (2)) can either be vapour, liquid or solid. Further it can consist of the same chemical material or another. In the case of the second phase being a solid of the same chemical material one speaks of grain boundaries. This case is very important when looking at polycrystalline materials.

Thermodynamical picture for solid gas interface

In the following thermodynamical equilibrium is assumed, as well as for simplicity (2) should be a vaporous phase.

The first (1) and the second (2) phase are always divided by some form of interface, what results in an interfacial energy . One can now ask whether this energy can be lowered by inserting a third phase (l) in between (1) and (2). Written in interfacial energies this would mean:

If this is the case then it is more efficient for the system to form a separating phase (3). The only possibility for the system to form such a layer is to take material of the solid and "melt" it to a quasi-liquid. In further notation there will be no distinction between quasi-liquid and liquid but one should always keep in mind that there is a difference. This difference to a real liquid becomes clear when looking at a very thin layer (l). As, due to the long range forces of the molecules of the solid material the liquid very near the solid still "feels" the order of crystalline solid and hence itself is in a state providing a not liquid like amount of order. As considering a very thin layer at the moment it is clear that the whole separating layer (l) is too well ordered for a liquid. Further comments on ordering can be found in the paragraph on Landau theory.

Now, looking closer at the thermodynamics of the newly introduced phase (l), its Gibbs energy can be written as:

| , |

where is the temperature, the pressure, the thickness of (l) corresponding to the number or particles in this case. and are the atomic density and the chemical potential in (l) and . Note that one has to consider that the interfacial energies can just be added to the Gibbs energy in this case. As noted before corresponds so the derivation to results in:

Where . Hence and differ and can be defined. Assuming that a Taylor expansion around the melting point is possible and using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation one can get the following results:

- For a long range potential assuming and :

- For short range potential of the form :

Where is in the order of molecular dimensions the specific melting heat and

These formulas also show that the more the temperature increases, the more increases the thickness of the premelt as this is energetically advantageous. This is the explanation why no overheating exists for this type of phase transition.[5]

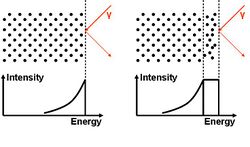

Lifshitz theory: Complete and incomplete premelting

With the help of the Lifshitz Theory on Casimir, respectively van der Waals, interactions of macroscopic bodies premelting can be viewed from an electrodynamical perspective. A good example for determining the difference between complete and incomplete premelting is ice. From vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) frequencies upwards the polarizability of ice is greater than that of water, at lower frequencies this is reversed. Assuming there is already a film of thickness on the solid it is easy for any components of electromagnetic waves to travel through the film in the direction perpendicular to the solid surface as long is small. Hence as long as the film is thin compared to the frequency interaction from the solid to the whole film is possible. But when gets large compared to typical VUV frequencies the electronic structure of the film will be too slow to pass the high frequencies to the other end of the liquid phase. Thus this end of the liquid phase feels only a retarded van der Waals interaction with the solid phase. Hence the attraction between the liquid molecules themselves will predominate and they will start forming droplets instead of thickening the film further. So the speed of light limits complete premelting. This makes it a question of solid and surface free energies whether complete premelting occurs. Complete surface melting will occur when is monotonically decreasing. If instead shows a global minimum at finite than the premelting will be incomplete. This implies: When the long range interactions in the system are attractive than there will be incomplete premelting — assuming the film thickness is larger than any repulsive interactions. Is the film thickness small compared to the range of the repulsive interactions present and the repulsive interactions are stronger than the attractive ones than complete premelting can occur. For van der Waals interactions Lifshitz theory can now calculate which type of premelting should occur for a special system. In fact small differences in systems can affect the type of premelting. For example, ice in an atmosphere of water vapour shows incomplete premelting, whereas the premelting of ice in air is complete.

For solid–solid interfaces it cannot be predicted in general whether the premelting is complete or incomplete when only considering van der Waals interactions. Here other types of interactions become very important. This also accounts for grain boundaries.[5]

Landau theory

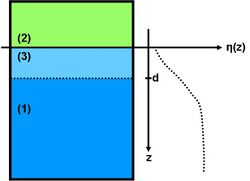

Most insight in the problem probably emerges when approaching the effect form Landau Theory. Which is a little bit problematic as the melting of a bulk in general has to be considered as a first order phase transition, meaning the order parameter jumps at . The derivation of Lipowski (basic geometry shown in fig.2) leads to the following results when :

Where is the order parameter at the border between (2) and (l), the so-called extrapolation length and a constant that enters the model and has to be determined using experiment and other models. Hence one can see that the order parameter in the liquid film can undergo a continuous phase transition for large enough extrapolation length. A further result is that what corresponds to the result of the thermodynamical model in the case of short range interactions. Landau Theory does not consider fluctuations like capillary waves, this could change the results qualitatively.[6]

Experimental proof for premelting

There are several techniques to prove the existence of a liquid layer on a well-ordered surface. Basically it is all about showing that there is a phase on top of the solid which has hardly any order (quasi-liquid, see fig. order parameter). One possibility was done by Frenken and van der Veen using proton scattering on a lead (Pb) single crystal (110) surface. First the surface was atomically cleaned in [UHV], because one obviously has to have a very well ordered surface for such experiments. Then they did proton shadowing and blocking measurements. An ideal shadowing and blocking measurements results in an energy spectrum of the scattered protons that shows only a peak for the first surface layer and nothing else. Due to the non ideality of the experiment the spectrum also shows effects of the underlying layers. That means the spectrum is not one well defined peak but has a tail to lower energies due to protons scattered on deeper layers which results in losing energies because of stopping. This is different for a liquid film on the surface: This film does hardly (to the meaning of hardly see Landau theory) have any order. So the effects of shadowing and blocking vanish what means all the liquid film contributes the same amount of scattered electrons to the signal. Therefore, the peak does not only have a tail, but also becomes broadened. During their measurements Frenken and van der Veen raised the temperature to the melting point and hence could show that with increasing temperature a disordered film formed on the surface in equilibrium with a still well ordered Pb crystal.[7]

Curvature, disorder and impurities

Up to here, an ideal surface was considered, but going beyond the idealized case there are several effects which influence premelting:

- Curvature: When the surface considered is not planar but exhibits a curvature premelting is affected. The rule is that whenever the surface is concave, viewed from the solid's perspective, then premelting is advanced. The fraction by which the thickness of the liquid film increases is given by , where r is the local radius of the curved surface. Therefore, it is also plausible that premelting starts in scratches or in corners of steps and hence has a flattening effect.

- Disordered solids: As disorder in the solid increases its local free energy, the local chemical potential of the disordered solid lies above the chemical potential of the ordered solid. In thermodynamic equilibrium the chemical potential of the premelted liquid film has to be equal to that of the disordered solid, so it can be concluded that disorder in the solid phase causes the effect of premelting to increase.

- Impurities: Consider the case of the depression of the ice melting temperature due to dissolved salt. For premelting the situation is far more difficult than one would expect from that simple statement. It starts with the Lifshitz theory which was roughly sketched above. But now the impurities cause screening in the liquid, they adsorb on the border between solid and liquid phase and all those effects make a general derivation of impurity effects impossible to state here. But it can be said that impurities have a great effect on the temperature from which on premelting can be observed and they especially affect the thickness of the layer. This however does not mean that the thickness is a monotone function in the concentration.[5]

Ice skating

The friction coefficient for ice, without a liquid film on the surface, is measured to be .[8] A comparable friction coefficient is that of rubber or bitumen (roughly 0.8), which would be very difficult to ice skate on. The friction coefficients needs to be around or below 0.005 for ice skating to be possible.[9] The reason ice skating is possible is because there is a thin film of water present between the blade of the ice skate and the ice. The origin of this water film has been a long-standing debate. There are three proposed mechanisms that could account for a film of liquid water on the ice surface:[10]

- Pressure Melting: James Thomson suggested as early as 1849 that expansion of water as it freezes implied that ice should melt upon compression. This idea was exploited by John Joly as a mechanism for ice skating, arguing that the pressure on the skates could melt ice and thereby create a lubricating film (1886).

- Premelting: Previously, Faraday and Tyndall had argued that the slipperiness of ice was due to the existence of a premelting film on the ice surface, irrespective of pressure.

- Friction: Bowden instead argued that heat generated from the ice skates moving, melts a small amount of ice under the blade.

While contributions from all three of these factors are usually in effect when ice skating, the scientific community has long debated over which is the dominating mechanism. For several decades it was common to explain the low friction of the skates on ice by pressure melting, but there are several recent arguments that contradict this hypothesis.[10] The strongest argument against pressure melting is that ice skating is still possible below temperatures under -20 °C (253K). At this temperature, a great deal of pressure (>100MPa) is required to induce melting. Just below -23 °C (250K), increasing the pressure can only form a different solid structure of ice (Ice III) since the isotherm no longer passes through the liquid phase on the phase diagram. While impurities in the ice will suppress the melting temperature, many materials scientists agree that pressure melting is not the dominant mechanism.[11] The thickness of the water film due to premelting is also limited at low temperatures. While the water film can reach thicknesses on the order of μm, at temperatures around -10 °C the thickness is on the order of nm. Although, De Koning et al. found in their measurements that the adding of impurities to the ice can lower the friction coefficient up to 15%. The friction coefficient increases with skating speed, which could yield different results depending on the skating technique and speeds.[9] While the pressure melting hypothesis may have been put to rest, the debate between premelting and friction as the dominant mechanism still rages on.

See also

References

- ↑ Faraday, Michael (1933). Faraday's Diary. IV. London, England: Bell and Sons. p. 79 (entry for September 8, 1842). https://archive.org/stream/faradaysdiarybei00fara_2#page/78/mode/2up.

- ↑ Tammann, G. (1910). "Zur Überhitzung von Kristallen" (in German). Zeitschrift für physikalische Chemie, Stöchiometrie und Verwandtschaftslehre 68 (3): 257–269. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x030529763&seq=269.

- ↑ Stranski, I. N. (July 1942). "Über den Schmelzvorgang bei nichtpolaren Kristallen" (in German). Naturwissenschaften 30: 425–433.

- ↑ Frenkel, J. (1946). Kinetic Theory of Liquids. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 136–156.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Dash, J.G.; Rempel, A.; Wettlaufer, J. (2006). "The physics of premelted ice and its geophysical consequences". Rev Mod Phys 78 (3): 695. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.78.695. Bibcode: 2006RvMP...78..695D.

- ↑ Lipowski, R. (1982). "Critical Surface Phenomena at First-Order Bulk Transitions". Phys. Rev. Lett. 49 (21): 1575–1578. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.49.1575. Bibcode: 1982PhRvL..49.1575L.

- ↑ Frenken, J.W.M. c; Van Der Veen, JF (1985). "Observation of Surface Melting". Phys. Rev. Lett. 54 (2): 134–137. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.134. PMID 10031263. Bibcode: 1985PhRvL..54..134F. https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/71364/Physical_Review_Letters_54oe1985oe134.pdf?sequence=1.

- ↑ Bluhm, H.; T. Inoue; M. Salmeron (2000). "Friction of ice measured using lateral force microscopy". Phys. Rev. B 61 (11): 7760. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.61.7760. Bibcode: 2000PhRvB..61.7760B. https://zenodo.org/record/1233739.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 De Koning, J.J.; G. De Groot; G.J. Van Ingen Schenau (1992). "Ice friction during speed skating". J Biomech 25 (6): 565–71. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(92)90099-M. PMID 1517252.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Why is Ice slippery? Rosenberg. pdf

- ↑ Colbeck, S.C. (1995). "Pressure melting and ice skating". Am J Phys 63 (10): 888–890. doi:10.1119/1.18028. Bibcode: 1995AmJPh..63..888C.

- Dimanov, A.; Ingrin, J. (1995). "Premelting and high-temperature diffusion of Ca in synthetic diopside: An increase of cation mobility". Physics and Chemistry of Minerals 22 (7): 437–442. doi:10.1007/BF00200321. Bibcode: 1995PCM....22..437D..

External links

- [1] Surface melting, Israel Institute of Technology

- [2] Robert Rosenberg: Why is Ice Slippery?; Physics Today, December 2005 (press release; journal article at DOI: 10.1063/1.4936299 requires subscription)

- [3] Kenneth Chang: Explaining Ice: The Answers Are Slippery; The New York Times, February 21, 2006 (requires subscription)

|

KSF

KSF