Proximity effect (superconductivity)

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

Proximity effect or Holm–Meissner effect is a term used in the field of superconductivity to describe phenomena that occur when a superconductor (S) is placed in contact with a "normal" (N) non-superconductor. Typically the critical temperature of the superconductor is suppressed and signs of weak superconductivity are observed in the normal material over mesoscopic distances. The proximity effect is known since the pioneering work by R. Holm and W. Meissner.[1] They have observed zero resistance in SNS pressed contacts, in which two superconducting metals are separated by a thin film of a non-superconducting (i.e. normal) metal. The discovery of the supercurrent in SNS contacts is sometimes mistakenly attributed to Brian Josephson's 1962 work, yet the effect was known long before his publication and was understood as the proximity effect.[2]

Origin of the effect

Electrons in the superconducting state of a superconductor are ordered in a very different way than in a normal metal, i.e. they are paired into Cooper pairs. Furthermore, electrons in a material cannot be said to have a definitive position because of the momentum-position complementarity. In solid state physics one generally chooses a momentum space basis, and all electron states are filled with electrons until the Fermi surface in a metal, or until the gap edge energy in the superconductor.

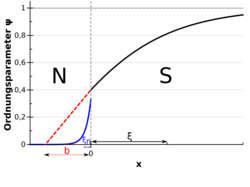

Because of the nonlocality of the electrons in metals, the properties of those electrons cannot change infinitely quickly. In a superconductor, the electrons are ordered as superconducting Cooper pairs; in a normal metal, the electron order is gapless (single-electron states are filled up to the Fermi surface). If the superconductor and normal metal are brought together, the electron order in the one system cannot infinitely abruptly change into the other order at the border. Instead, the paired state in the superconducting layer is carried over to the normal metal, where the pairing is destroyed by scattering events, causing the Cooper pairs to lose their coherence. For very clean metals, such as copper, the pairing can persist for hundreds of microns.

Conversely, the (gapless) electron order present in the normal metal is also carried over to the superconductor in that the superconducting gap is lowered near the interface.

The microscopic model describing this behavior in terms of single electron processes is called Andreev reflection. It describes how electrons in one material take on the order of the neighboring layer by taking into account interface transparency and the states (in the other material) from which the electrons can scatter.

Overview

As a contact effect, the proximity effect is closely related to thermoelectric phenomena like the Peltier effect or the formation of pn junctions in semiconductors. The proximity effect enhancement of is largest when the normal material is a metal with a large diffusivity rather than an insulator (I). Proximity-effect suppression of in a spin-singlet superconductor is largest when the normal material is ferromagnetic, as the presence of the internal magnetic field weakens superconductivity (Cooper pairs breaking).

Research

The study of S/N, S/I and S/S' (S' is lower superconductor) bilayers and multilayers has been a particularly active area of superconducting proximity effect research. The behavior of the compound structure in the direction parallel to the interface differs from that perpendicular to the interface. In type II superconductors exposed to a magnetic field parallel to the interface, vortex defects will preferentially nucleate in the N or I layers and a discontinuity in behavior is observed when an increasing field forces them into the S layers. In type I superconductors, flux will similarly first penetrate N layers. Similar qualitative changes in behavior do not occur when a magnetic field is applied perpendicular to the S/I or S/N interface. In S/N and S/I multilayers at low temperatures, the long penetration depths and coherence lengths of the Cooper pairs will allow the S layers to maintain a mutual, three-dimensional quantum state. As temperature is increased, communication between the S layers is destroyed resulting in a crossover to two-dimensional behavior. The anisotropic behavior of S/N, S/I and S/S' bilayers and multilayers has served as a basis for understanding the far more complex critical field phenomena observed in the highly anisotropic cuprate high-temperature superconductors.

Recently the Holm–Meissner proximity effect was observed in graphene by the Morpurgo research group.[3] The experiments have been done on nanometer scale devices made of single graphene layers with superimposed superconducting electrodes made of 10 nm Titanium and 70 nm Aluminum films. Aluminum is a superconductor, which is responsible for inducing superconductivity into graphene. The distance between the electrodes was in the range between 100 nm and 500 nm. The proximity effect is manifested by observations of a supercurrent, i.e. a current flowing through the graphene junction with zero voltage on the junction. By using the gate electrodes the researches have shown that the proximity effect occurs when the carriers in the graphene are electrons as well as when the carriers are holes. The critical current of the devices was above zero even at the Dirac point.

Abrikosov vortex and proximity effect

Here is shown, that a quantum vortex with a well-defined core can exist in a rather thick normal metal, proximized with a superconductor.[4]

See also

- Physics:Andreev reflection – Scattering process at the normal-metal-superconductor interface

- Physics:Josephson effect – Quantum physical phenomenon

References

- ↑ Holm, R.; Meissner, W. (1932). "Messungen mit Hilfe von flüssigem Helium. XIII". Z. Phys. 74 (11–12): 715. doi:10.1007/bf01340420. Bibcode: 1932ZPhy...74..715H.

- ↑ Meissner, H. (1960). "Superconductivity in contacts with interposed barriers". Phys. Rev. 117 (3): 672–680. doi:10.1103/physrev.117.672. Bibcode: 1960PhRv..117..672M.

- ↑ Heersche, H.B. (2007). "Bipolar Supercurrent in Graphene". Nature 446 (7131): 56–59. doi:10.1038/nature05555. PMID 17330038. Bibcode: 2007Natur.446...56H.

- ↑ Stolyarov, Vasily S.; Cren, Tristan; Brun, Christophe; Golovchanskiy, Igor A.; Skryabina, Olga V.; Kasatonov, Daniil I.; Khapaev, Mikhail M.; Kupriyanov, Mikhail Yu. et al. (11 June 2018). "Expansion of a superconducting vortex core into a diffusive metal". Nature Communications 9 (1): 2277. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04582-1. PMID 29891870. Bibcode: 2018NatCo...9.2277S.

- Superconductivity of Metals and Alloys by P.G. de Gennes, ISBN 0-201-40842-2, a textbook which devotes significant space to the superconducting proximity effect (called "boundary effect" in the book).

|

KSF

KSF