Relationship between mathematics and physics

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

The relationship between mathematics and physics has been a subject of study of philosophers, mathematicians and physicists since antiquity, and more recently also by historians and educators.[2] Generally considered a relationship of great intimacy,[3] mathematics has been described as "an essential tool for physics"[4] and physics has been described as "a rich source of inspiration and insight in mathematics".[5]

In his work Physics, one of the topics treated by Aristotle is about how the study carried out by mathematicians differs from that carried out by physicists.[6] Considerations about mathematics being the language of nature can be found in the ideas of the Pythagoreans: the convictions that "Numbers rule the world" and "All is number",[7][8] and two millennia later were also expressed by Galileo Galilei: "The book of nature is written in the language of mathematics".[9][10]

Before giving a mathematical proof for the formula for the volume of a sphere, Archimedes used physical reasoning to discover the solution (imagining the balancing of bodies on a scale).[11] From the seventeenth century, many of the most important advances in mathematics appeared motivated by the study of physics, and this continued in the following centuries (although in the nineteenth century mathematics started to become increasingly independent from physics).[12][13] The creation and development of calculus were strongly linked to the needs of physics:[14] There was a need for a new mathematical language to deal with the new dynamics that had arisen from the work of scholars such as Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton.[15] During this period there was little distinction between physics and mathematics;[16] as an example, Newton regarded geometry as a branch of mechanics.[17] As time progressed, the mathematics used in physics has become increasingly sophisticated, as in the case of superstring theory.[18] Unconventional connections between the two fields are found all the time as in 1975 Wu–Yang dictionary, that related concepts of gauge theory with differential geometry.[19]

Physics is not math

Despite the close relationship between math and physics, they are not synonyms. In mathematics objects can be defined exactly and logically related, but the object need have no relationship to experimental measurements. In physics, definitions are abstractions or idealizations, approximations adequate when compared to the natural world. For example, Newton built a physical model around definitions like based on observations, leading to the development of calculus and highly accurate planetary mechanics, but later this definition was superseded by improved models of mechanics.[20]

Philosophical problems

Some of the problems considered in the philosophy of mathematics are the following:

- Explain the effectiveness of mathematics in the study of the physical world: "At this point an enigma presents itself which in all ages has agitated inquiring minds. How can it be that mathematics, being after all a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality?" —Albert Einstein, in Geometry and Experience (1921).[21]

- Clearly delineate mathematics and physics: For some results or discoveries, it is difficult to say to which area they belong: to the mathematics or to physics.[22]

- What is the geometry of physical space?[23]

- What is the origin of the axioms of mathematics?[24]

- How does the already existing mathematics influence in the creation and development of physical theories?[25]

- Is arithmetic analytic or synthetic? (from Kant, see Analytic–synthetic distinction)[26]

- What is essentially different between doing a physical experiment to see the result and making a mathematical calculation to see the result? (from the Turing–Wittgenstein debate)[27]

- Do Gödel's incompleteness theorems imply that physical theories will always be incomplete? (from Stephen Hawking)[28][29]

- Is mathematics invented or discovered? (millennia-old question, raised among others by Mario Livio)[30]

Education

In recent times the two disciplines have most often been taught separately, despite all the interrelations between physics and mathematics.[31] This led some professional mathematicians who were also interested in mathematics education, such as Felix Klein, Richard Courant, Vladimir Arnold and Morris Kline, to strongly advocate teaching mathematics in a way more closely related to the physical sciences.[32][33]

See also

- Pure mathematics

- Applied mathematics

- Theoretical physics

- Mathematical physics

- Non-Euclidean geometry

- Fourier series

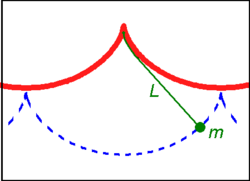

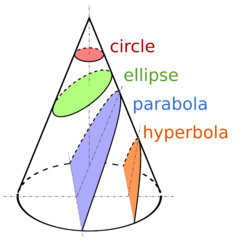

- Conic section

- Kepler's laws of planetary motion

- Saving the phenomena

- Positron § History

- The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences

- Mathematical universe hypothesis

- Zeno's paradoxes

- Axiomatic system

- Mathematical model

- Hilbert's sixth problem

- Empiricism

- Logicism

- Formalism

- Mathematics of general relativity

- Bourbaki

- Experimental mathematics

- History of Maxwell's equations

- Philosophy of mathematics § Platonism

- History of astronomy

- Why Johnny Can't Add

References

- ↑ Jed Z. Buchwald; Robert Fox (10 October 2013). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Physics. OUP Oxford. pp. 128. ISBN 978-0-19-151019-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=1SxoAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA128.

- ↑ Uhden, Olaf; Karam, Ricardo; Pietrocola, Maurício; Pospiech, Gesche (20 October 2011). "Modelling Mathematical Reasoning in Physics Education". Science & Education 21 (4): 485–506. doi:10.1007/s11191-011-9396-6. Bibcode: 2012Sc&Ed..21..485U.

- ↑ Francis Bailly; Giuseppe Longo (2011). Mathematics and the Natural Sciences: The Physical Singularity of Life. World Scientific. pp. 149. ISBN 978-1-84816-693-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=7-dGHyIyI-AC&pg=PA149.

- ↑ Sanjay Moreshwar Wagh; Dilip Abasaheb Deshpande (27 September 2012). Essentials of Physics. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.. pp. 3. ISBN 978-81-203-4642-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=-DmfVjBUPksC&pg=PA3.

- ↑ Atiyah, Michael (1990). "On the Work of Edward Witten". International Congress of Mathematicians. Japan. pp. 31–35. http://www.mathunion.org/ICM/ICM1990.1/Main/icm1990.1.0031.0036.ocr.pdf.

- ↑ Lear, Jonathan (1990). Aristotle: the desire to understand (Repr. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 232. ISBN 9780521347624. https://archive.org/details/aristotledesiret0000lear/page/232.

- ↑ Gerard Assayag; Hans G. Feichtinger; José-Francisco Rodrigues (10 July 2002). Mathematics and Music: A Diderot Mathematical Forum. Springer. pp. 216. ISBN 978-3-540-43727-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=bjsD8ClsFKEC&pg=PA216.

- ↑ Al-Rasasi, Ibrahim (21 June 2004). "All is number". King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals. http://faculty.kfupm.edu.sa/math/irasasi/Allisnumber.pdf.

- ↑ Aharon Kantorovich (1 July 1993). Scientific Discovery: Logic and Tinkering. SUNY Press. pp. 59. ISBN 978-0-7914-1478-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=vMFc43w0FfEC&pg=PA59.

- ↑ Kyle Forinash, William Rumsey, Chris Lang, Galileo's Mathematical Language of Nature .

- ↑ Arthur Mazer (26 September 2011). The Ellipse: A Historical and Mathematical Journey. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 5. ISBN 978-1-118-21143-4. Bibcode: 2010ehmj.book.....M. https://books.google.com/books?id=twWkDe1Y9YQC&pg=SA5-PA28.

- ↑ E. J. Post, A History of Physics as an Exercise in Philosophy, p. 76.

- ↑ Arkady Plotnitsky, Niels Bohr and Complementarity: An Introduction, p. 177.

- ↑ Roger G. Newton (1997). The Truth of Science: Physical Theories and Reality. Harvard University Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-674-91092-8. https://archive.org/details/truthofscienceph00newt.

- ↑ Eoin P. O'Neill (editor), What Did You Do Today, Professor?: Fifteen Illuminating Responses from Trinity College Dublin, p. 62.

- ↑ Timothy Gowers; June Barrow-Green; Imre Leader (18 July 2010). The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Princeton University Press. pp. 7. ISBN 978-1-4008-3039-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZOfUsvemJDMC&pg=PA7.

- ↑ David E. Rowe (2008). "Euclidean Geometry and Physical Space". The Mathematical Intelligencer 28 (2): 51–59. doi:10.1007/BF02987157.

- ↑ "String theories". Four Peaks Technologies. http://www.particlecentral.com/strings_page.html.

- ↑ Zeidler, Eberhard (2008-09-03) (in en). Quantum Field Theory II: Quantum Electrodynamics: A Bridge between Mathematicians and Physicists. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-85377-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pk9yyC239scC&q=dictionary.

- ↑ Feynman, Richard P. (2011). "Characteristics of Force". The Feynman lectures on physics. Volume 1: Mainly mechanics, radiation, and heat (The new millennium edition, paperback first published ed.). New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02493-3. https://www.feynmanlectures.caltech.edu/I_12.html.

- ↑ Albert Einstein, Geometry and Experience.

- ↑ Pierre Bergé, Des rythmes au chaos.

- ↑ Gary Carl Hatfield (1990). The Natural and the Normative: Theories of Spatial Perception from Kant to Helmholtz. MIT Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-262-08086-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=JikeeDbYeUQC&pg=PA223.

- ↑ Gila Hanna; Hans Niels Jahnke; Helmut Pulte (4 December 2009). Explanation and Proof in Mathematics: Philosophical and Educational Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-4419-0576-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=3bLHye8kSAwC&pg=PA29.

- ↑ "FQXi Community Trick or Truth: the Mysterious Connection Between Physics and Mathematics". http://fqxi.org/community/essay/rules.

- ↑ James Van Cleve Professor of Philosophy Brown University (16 July 1999). Problems from Kant. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-534701-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=6WHAgt-Mg1AC&pg=PA22.

- ↑ Ludwig Wittgenstein; R. G. Bosanquet; Cora Diamond (15 October 1989). Wittgenstein's Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics, Cambridge, 1939. University of Chicago Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-226-90426-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=d4YUZVq1JSEC&pg=PA96.

- ↑ Pudlák, Pavel (2013). Logical Foundations of Mathematics and Computational Complexity: A Gentle Introduction. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 659. ISBN 978-3-319-00119-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=obxDAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA659.

- ↑ "Stephen Hawking. "Godel and the End of the Universe"". http://www.hawking.org.uk/godel-and-the-end-of-physics.html.

- ↑ Mario Livio (August 2011). "Why math works?". Scientific American: 80–83. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-math-works/.

- ↑ Karam; Pospiech; & Pietrocola (2010). "Mathematics in physics lessons: developing structural skills"

- ↑ Stakhov "Dirac’s Principle of Mathematical Beauty, Mathematics of Harmony"

- ↑ Richard Lesh; Peter L. Galbraith; Christopher R. Haines; Andrew Hurford (2009). Modeling Students' Mathematical Modeling Competencies: ICTMA 13. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4419-0561-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jj5tfi2594kC&pg=PA14.

Further reading

- Arnold, V. I. (1999). "Mathematics and physics: mother and daughter or sisters?". Physics-Uspekhi 42 (12): 1205–1217. doi:10.1070/pu1999v042n12abeh000673. Bibcode: 1999PhyU...42.1205A.

- Arnold, V. I. (1998). "On teaching mathematics". Russian Mathematical Surveys 53 (1): 229–236. doi:10.1070/RM1998v053n01ABEH000005. Bibcode: 1998RuMaS..53..229A. http://pauli.uni-muenster.de/~munsteg/arnold.html. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- Atiyah, M.; Dijkgraaf, R.; Hitchin, N. (1 February 2010). "Geometry and physics". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 368 (1914): 913–926. doi:10.1098/rsta.2009.0227. PMID 20123740. Bibcode: 2010RSPTA.368..913A.

- Boniolo, Giovanni; Budinich, Paolo; Trobok, Majda, eds (2005). The Role of Mathematics in Physical Sciences: Interdisciplinary and Philosophical Aspects. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 9781402031069.

- Colyvan, Mark (2001). "The Miracle of Applied Mathematics". Synthese 127 (3): 265–277. doi:10.1023/A:1010309227321. http://www.colyvan.com/papers/miracle.pdf. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- Dirac, Paul (1938–1939). "The Relation between Mathematics and Physics". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 59 Part II: 122–129. http://www.damtp.cam.ac.uk/events/strings02/dirac/speach.html. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Feynman, Richard P. (1992). "The Relation of Mathematics to Physics". The Character of Physical Law (Reprint ed.). London: Penguin Books. pp. 35–58. ISBN 978-0140175059.

- Hardy, G. H. (2005). A Mathematician's Apology (First electronic ed.). University of Alberta Mathematical Sciences Society. http://www.math.ualberta.ca/mss/misc/A%20Mathematician%27s%20Apology.pdf. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- Hitchin, Nigel (2007). "Interaction between mathematics and physics". ARBOR Ciencia, Pensamiento y Cultura 725. http://arbor.revistas.csic.es/index.php/arbor/article/viewFile/115/116. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- Harvey, Alex (2012). "The Reasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Physical Sciences". General Relativity and Gravitation 43 (2011): 3057–3064. doi:10.1007/s10714-011-1248-9. Bibcode: 2011GReGr..43.3657H.

- Neumann, John von (1947). "The Mathematician". Works of the Mind 1 (1): 180–196. (part 1) (part 2).

- Poincaré, Henri (1907). The Value of Science. New York: The Science Press. http://www3.nd.edu/~powers/ame.60611/poincare.pdf.

- Schlager, Neil; Lauer, Josh, eds (2000). "The Intimate Relation between Mathematics and Physics". Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. 7: 1950 to Present. Gale Group. pp. 226–229. ISBN 978-0-7876-3939-6. https://archive.org/details/scienceitstimesu0000unse/page/226.

- Vafa, Cumrun (2000). "On the Future of Mathematics/Physics Interaction". Mathematics: Frontiers and Perspectives. USA: AMS. pp. 321–328. ISBN 978-0-8218-2070-4.

- Witten, Edward (1986). "Physics and Geometry". Proceedings of the International Conference of Mathematicians. Berkeley, California. pp. 267–303. http://www.mathunion.org/ICM/ICM1986.1/Main/icm1986.1.0267.0306.ocr.pdf. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- Eugene Wigner (1960). "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences". Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics 13 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1002/cpa.3160130102. Bibcode: 1960CPAM...13....1W. http://www.dartmouth.edu/~matc/MathDrama/reading/Wigner.html. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

External links

- Gregory W. Moore – Physical Mathematics and the Future (July 4, 2014)

- IOP Institute of Physics – Mathematical Physics: What is it and why do we need it? (September 2014)

|

KSF

KSF