String field theory

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

| String theory |

|---|

|

| Fundamental objects |

| Perturbative theory |

| Non-perturbative results |

| Phenomenology |

| Mathematics |

String field theory (SFT) is a formalism in string theory in which the dynamics of relativistic strings is reformulated in the language of quantum field theory. This is accomplished at the level of perturbation theory by finding a collection of vertices for joining and splitting strings, as well as string propagators, that give a Feynman diagram-like expansion for string scattering amplitudes. In most string field theories, this expansion is encoded by a classical action found by second-quantizing the free string and adding interaction terms. As is usually the case in second quantization, a classical field configuration of the second-quantized theory is given by a wave function in the original theory. In the case of string field theory, this implies that a classical configuration, usually called the string field, is given by an element of the free string Fock space.

The principal advantages of the formalism are that it allows the computation of off-shell amplitudes and, when a classical action is available, gives non-perturbative information that cannot be seen directly from the standard genus expansion of string scattering. In particular, following the work of Ashoke Sen,[1] it has been useful in the study of tachyon condensation on unstable D-branes. It has also had applications to topological string theory,[2] non-commutative geometry,[3] and strings in low dimensions.[4]

String field theories come in a number of varieties depending on which type of string is second quantized: Open string field theories describe the scattering of open strings, closed string field theories describe closed strings, while open-closed string field theories include both open and closed strings.

In addition, depending on the method used to fix the worldsheet diffeomorphisms and conformal transformations in the original free string theory, the resulting string field theories can be very different. Using light cone gauge, yields light-cone string field theories whereas using BRST quantization, one finds covariant string field theories. There are also hybrid string field theories, known as covariantized light-cone string field theories which use elements of both light-cone and BRST gauge-fixed string field theories.[5]

A final form of string field theory, known as background independent open string field theory, takes a very different form; instead of second quantizing the worldsheet string theory, it second quantizes the space of two-dimensional quantum field theories.[6]

Light-cone string field theory

Light-cone string field theories were introduced by Stanley Mandelstam[7][8] and developed by Mandelstam, Michael Green, John Schwarz and Lars Brink.[9][10][11][12][13] An explicit description of the second-quantization of the light-cone string was given by Michio Kaku and Keiji Kikkawa.[14][15]

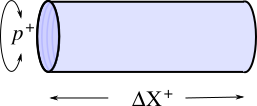

Light-cone string field theories were the first string field theories to be constructed and are based on the simplicity of string scattering in light-cone gauge. For example, in the bosonic closed string case, the worldsheet scattering diagrams naturally take a Feynman diagram-like form, being built from two ingredients, a propagator,

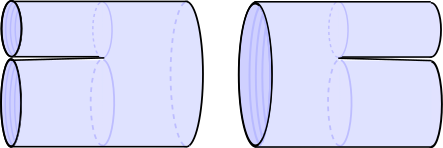

and two vertices for splitting and joining strings, which can be used to glue three propagators together,

These vertices and propagators produce a single cover of the moduli space of -point closed string scattering amplitudes so no higher order vertices are required.[16] Similar vertices exist for the open string.

When one considers light-cone quantized superstrings, the discussion is more subtle as divergences can arise when the light-cone vertices collide.[17] To produce a consistent theory, it is necessary to introduce higher order vertices, called contact terms, to cancel the divergences.

Light-cone string field theories have the disadvantage that they break manifest Lorentz invariance. However, in backgrounds with light-like Killing vectors, they can considerably simplify the quantization of the string action. Moreover, until the advent of the Berkovits string[18] it was the only known method for quantizing strings in the presence of Ramond–Ramond fields. In recent research, light-cone string field theory played an important role in understanding strings in pp-wave backgrounds.[19]

Free covariant string field theory

An important step in the construction of covariant string field theories (preserving manifest Lorentz invariance) was the construction of a covariant kinetic term. This kinetic term can be considered a string field theory in its own right: the string field theory of free strings. Since the work of Warren Siegel,[20] it has been standard to first BRST-quantize the free string theory and then second quantize so that the classical fields of the string field theory include ghosts as well as matter fields. For example, in the case of the bosonic open string theory in 26-dimensional flat spacetime, a general element of the Fock-space of the BRST quantized string takes the form (in radial quantization in the upper half plane),

where is the free string vacuum and the dots represent more massive fields. In the language of worldsheet string theory, , , and represent the amplitudes for the string to be found in the various basis states. After second quantization, they are interpreted instead as classical fields representing the tachyon , gauge field and a ghost field .

In the worldsheet string theory, the unphysical elements of the Fock space are removed by imposing the condition as well as the equivalence relation . After second quantization, the equivalence relation is interpreted as a gauge invariance, whereas the condition that is physical is interpreted as an equation of motion. Because the physical fields live at ghostnumber one, it is also assumed that the string field is a ghostnumber one element of the Fock space.

In the case of the open bosonic string a gauge-unfixed action with the appropriate symmetries and equations of motion was originally obtained by André Neveu, Hermann Nicolai and Peter C. West.[21] It is given by

where is the BPZ-dual of .[22]

For the bosonic closed string, construction of a BRST-invariant kinetic term requires additionally that one impose and . The kinetic term is then

Additional considerations are required for the superstrings to deal with the superghost zero-modes.

Witten's cubic open string field theory

The best studied and simplest of covariant interacting string field theories was constructed by Edward Witten.[23] It describes the dynamics of bosonic open strings and is given by adding to the free open string action a cubic vertex:

- ,

where, as in the free case, is a ghostnumber one element of the BRST-quantized free bosonic open-string Fock-space.

The cubic vertex,

is a trilinear map which takes three string fields of total ghostnumber three and yields a number. Following Witten, who was motivated by ideas from noncommutative geometry, it is conventional to introduce the -product defined implicitly through

The -product and cubic vertex satisfy a number of important properties (allowing the to be general ghost number fields):

- Cyclicity :

- BRST invariance :

For the -product, this implies that acts as a graded derivation

- Associativity

In terms of the cubic vertex,

In these equations, denotes the ghost number of .

Gauge invariance

These properties of the cubic vertex are sufficient to show that is invariant under the Yang–Mills-like gauge transformation,

where is an infinitesimal gauge parameter. Finite gauge transformations take the form

where the exponential is defined by,

Equations of motion

The equations of motion are given by the following equation:

Because the string field is an infinite collection of ordinary classical fields, these equations represent an infinite collection of non-linear coupled differential equations. There have been two approaches to finding solutions: First, numerically, one can truncate the string field to include only fields with mass less than a fixed bound, a procedure known as "level truncation".[24] This reduces the equations of motion to a finite number of coupled differential equations and has led to the discovery of many solutions.[25][26] Second, following the work of Martin Schnabl [27] one can seek analytic solutions by carefully picking an ansatz which has simple behavior under star multiplication and action by the BRST operator. This has led to solutions representing marginal deformations, the tachyon vacuum solution[28] and time-independent D-brane systems.[29]

Quantization

To consistently quantize one has to fix a gauge. The traditional choice has been Feynman–Siegel gauge,

Because the gauge transformations are themselves redundant (there are gauge transformations of the gauge transformations), the gauge fixing procedure requires introducing an infinite number of ghosts via the BV formalism.[30] The complete gauge fixed action is given by

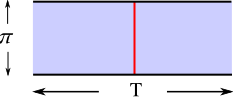

where the field is now allowed to be of arbitrary ghostnumber. In this gauge, the Feynman diagrams are constructed from a single propagator and vertex. The propagator takes the form of a strip of worldsheet of width and length

There is also an insertion of an integral of the -ghost along the red line. The modulus, is integrated from 0 to .

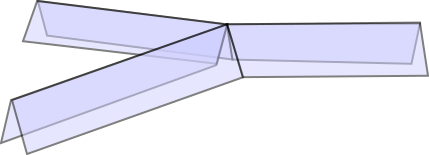

The three vertex can be described as a way of gluing three propagators together, as shown in the following picture:

In order to represent the vertex embedded in three dimensions, the propagators have been folded in half along their midpoints. The resulting geometry is completely flat except for a single curvature singularity where the midpoints of the three propagators meet.

These Feynman diagrams generate a complete cover of the moduli space of open string scattering diagrams. It follows that, for on-shell amplitudes, the n-point open string amplitudes computed using Witten's open string field theory are identical to those computed using standard worldsheet methods.[31][32]

Supersymmetric covariant open string field theories

There are two main constructions of supersymmetric extensions of Witten's cubic open string field theory. The first is very similar in form to its bosonic cousin and is known as modified cubic superstring field theory. The second, due to Nathan Berkovits is very different and is based on a WZW-type action.

Modified cubic superstring field theory

The first consistent extension of Witten's bosonic open string field theory to the RNS string was constructed by Christian Preitschopf, Charles Thorn and Scott Yost and independently by Irina Aref'eva, P. B. Medvedev and A. P. Zubarev.[33][34] The NS string field is taken to be a ghostnumber one picture zero string field in the small Hilbert space (i.e. ). The action takes a very similar form to bosonic action,

where,

is the inverse picture changing operator. The suggested picture number extension of this theory to the Ramond sector might be problematic.

This action has been shown to reproduce tree-level amplitudes and has a tachyon vacuum solution with the correct energy.[35] The one subtlety in the action is the insertion of picture changing operators at the midpoint, which imply that the linearized equations of motion take the form

Because has a non-trivial kernel, there are potentially extra solutions that are not in the cohomology of .[36] However, such solutions would have operator insertions near the midpoint and would be potentially singular, and importance of this problem remains unclear.

Berkovits superstring field theory

A very different supersymmetric action for the open string was constructed by Nathan Berkovits. It takes the form[37]

where all of the products are performed using the -product including the anticommutator , and is any string field such that and . The string field is taken to be in the NS sector of the large Hilbert space, i.e. including the zero mode of . It is not known how to incorporate the R sector, although some preliminary ideas exist.[38]

The equations of motion take the form

The action is invariant under the gauge transformation

The principal advantage of this action is that it free from any insertions of picture-changing operators. It has been shown to reproduce correctly tree level amplitudes[39] and has been found, numerically, to have a tachyon vacuum with appropriate energy.[40][41] The known analytic solutions to the classical equations of motion include the tachyon vacuum[42] and marginal deformations.

Other formulations of covariant open superstring field theory

A formulation of superstring field theory using the non-minimal pure-spinor variables was introduced by Berkovits.[43] The action is cubic and includes a midpoint insertion whose kernel is trivial. As always within the pure-spinor formulation, the Ramond sector can be easily treated. However, it is not known how to incorporate the GSO- sectors into the formalism.

In an attempt to resolve the allegedly problematic midpoint insertion of the modified cubic theory, Berkovits and Siegel proposed a superstring field theory based on a non-minimal extension of the RNS string,[44] which uses a midpoint insertion with no kernel. It is not clear if such insertions are in any way better than midpoint insertions with non-trivial kernels.

Covariant closed string field theory

Covariant closed string field theories are considerably more complicated than their open string cousins. Even if one wants to construct a string field theory which only reproduces tree-level interactions between closed strings, the classical action must contain an infinite number of vertices [45] consisting of string polyhedra.[46][47]

If one demands that on-shell scattering diagrams be reproduced to all orders in the string coupling, one must also include additional vertices arising from higher genus (and hence higher order in ) as well. In general, a manifestly BV invariant, quantizable action takes the form[48]

where denotes an th order vertex arising from a genus surface and is the closed string coupling. The structure of the vertices is in principle determined by a minimal area prescription,[49] although, even for the polyhedral vertices, explicit computations have only been performed to quintic order.[50][51]

Covariant heterotic string field theory

A formulation of the NS sector of the heterotic string was given by Berkovits, Okawa and Zwiebach.[52] The formulation amalgamates bosonic closed string field theory with Berkovits' superstring field theory.

See also

- Conformal field theory

- F-theory

- Fuzzballs

- List of string theory topics

- Little string theory

- Loop quantum gravity

- Relationship between string theory and quantum field theory

- String cosmology

- Supergravity

- The Elegant Universe

- Zeta function regularization

References

- ↑ Sen, Ashoke (1999-12-29). "Universality of the tachyon potential". Journal of High Energy Physics 1999 (12): 027. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/1999/12/027. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 1999JHEP...12..027S.

- ↑ E. Witten, "Chern–Simons gauge theory as a string theory", Prog. Math. 133 637, (1995)

- ↑ E. Witten, "Noncommutative tachyons and string field theory", hep-th/0006071

- ↑ Gaiotto, Davide; Rastelli, Leonardo (2005-07-25). "A paradigm of open/closed duality Liouville D-branes and the Kontsevich model". Journal of High Energy Physics 2005 (7): 053. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2005/07/053. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2005JHEP...07..053G.

- ↑ Hata, Hiroyuki; Itoh, Katsumi; Kugo, Taichiro; Kunitomo, Hiroshi; Ogawa, Kaku (1986). "Manifestly covariant field theory of interacting string I". Physics Letters B (Elsevier BV) 172 (2): 186–194. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(86)90834-8. ISSN 0370-2693. Bibcode: 1986PhLB..172..186H.

- ↑ Witten, Edward (1992-12-15). "On background-independent open-string field theory". Physical Review D 46 (12): 5467–5473. doi:10.1103/physrevd.46.5467. ISSN 0556-2821. PMID 10014938. Bibcode: 1992PhRvD..46.5467W.

- ↑ Mandelstam, S. (1973). "Interacting-string picture of dual-resonance models". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 64: 205–235. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(73)90622-6. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1973NuPhB..64..205M.

- ↑ Mandelstam, S. (1974). "Interacting-string picture of the Neveu-Schwarz-Ramond model". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 69 (1): 77–106. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(74)90127-8. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1974NuPhB..69...77M. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/73m8j1dz.

- ↑ Green, Michael B.; Schwarz, John H. (1982). "Supersymmetric dual string theory: (II). Vertices and trees". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 198 (2): 252–268. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(82)90556-9. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1982NuPhB.198..252G.

- ↑ Green, Michael B.; Schwarz, John H. (1983). "Superstring interactions". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 218 (1): 43–88. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(83)90475-3. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1983NuPhB.218...43G.

- ↑ Green, Michael B.; Schwarz, John H.; Brink, Lars (1983). "Superfield theory of type (II) superstrings". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 219 (2): 437–478. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(83)90651-x. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1983NuPhB.219..437G.

- ↑ Green, Michael B.; Schwarz, John H. (1984). "Superstring field theory". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 243 (3): 475–536. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(84)90488-7. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1984NuPhB.243..475G.

- ↑ Mandelstam, Stanley (1986). "Interacting-String Picture of the Fermionic String". Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement (Oxford University Press (OUP)) 86: 163–170. doi:10.1143/ptps.86.163. ISSN 0375-9687. Bibcode: 1986PThPS..86..163M.

- ↑ Kaku, Michio; Kikkawa, K. (1974-08-15). "Field theory of relativistic strings. I. Trees". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 10 (4): 1110–1133. doi:10.1103/physrevd.10.1110. ISSN 0556-2821. Bibcode: 1974PhRvD..10.1110K.

- ↑ Kaku, Michio; Kikkawa, K. (1974-09-15). "Field theory of relativistic strings. II. Loops and Pomerons". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 10 (6): 1823–1843. doi:10.1103/physrevd.10.1823. ISSN 0556-2821. Bibcode: 1974PhRvD..10.1823K.

- ↑ D'Hoker, Eric; Giddings, Steven B. (1987). "Unitarity of the closed bosonic Polyakov string". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 291: 90–112. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(87)90466-4. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1987NuPhB.291...90D.

- ↑ Greensite, J.; Klinkhamer, F.R. (1987). "New interactions for superstrings". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 281 (1–2): 269–288. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(87)90256-2. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1987NuPhB.281..269G.

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan (2000-04-15). "Super-Poincare covariant quantization of the superstring". Journal of High Energy Physics 2000 (4): 018. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2000/04/018. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2000JHEP...04..018B.

- ↑ M. Spradlin and A. Volovich, "Light-cone string field theory in a plane wave", Lectures given at ICTP Spring School on Superstring Theory and Related Topics, Trieste, Italy, 31 Mar – 8 Apr (2003) hep-th/0310033.

- ↑ W. Siegel, "String Field Theory Via BRST", in Santa Barbara 1985, Proceedings, Unified String Theories, 593;

W. Siegel, "Introduction to string field theory", Adv. Ser. Math. Phys. 8. Reprinted as hep-th/0107094 - ↑ Neveu, A.; Nicolai, H.; West, P. (1986). "New symmetries and ghost structure of covariant string theories". Physics Letters B (Elsevier BV) 167 (3): 307–314. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(86)90351-5. ISSN 0370-2693. Bibcode: 1986PhLB..167..307N. https://cds.cern.ch/record/164099.

- ↑ Belavin, A.A.; Polyakov, A.M.; Zamolodchikov, A.B. (1984). "Infinite conformal symmetry in two-dimensional quantum field theory". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 241 (2): 333–380. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(84)90052-x. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1984NuPhB.241..333B. https://cds.cern.ch/record/152341.

- ↑ Witten, Edward (1986). "Non-commutative geometry and string field theory". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 268 (2): 253–294. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(86)90155-0. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1986NuPhB.268..253W.

- ↑ Kostelecký, V. Alan; Samuel, Stuart (1989-01-15). "Spontaneous breaking of Lorentz symmetry in string theory". Physical Review D (American Physical Society (APS)) 39 (2): 683–685. doi:10.1103/physrevd.39.683. ISSN 0556-2821. PMID 9959689. Bibcode: 1989PhRvD..39..683K.

- ↑ Zwiebach, Barton (2001). "Is the String Field Big Enough?". Fortschritte der Physik (Wiley) 49 (4–6): 387. doi:10.1002/1521-3978(200105)49:4/6<387::aid-prop387>3.0.co;2-z. ISSN 0015-8208. Bibcode: 2001ForPh..49..387Z.

- ↑ Taylor, Washington; Zwiebach, Barton (2004). "Strings, Branes and Extra Dimensions". World Scientific. pp. 641–670. doi:10.1142/9789812702821_0012. ISBN 978-981-238-788-2.

- ↑ Schnabl, Martin (2006). "Analytic solution for tachyon condensation in open string field theory". Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 10 (4): 433–501. doi:10.4310/atmp.2006.v10.n4.a1. ISSN 1095-0761.

- ↑ Fuchs, Ehud; Kroyter, Michael (2011). "Analytical solutions of open string field theory". Physics Reports 502 (4–5): 89–149. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2011.01.003. ISSN 0370-1573. Bibcode: 2011PhR...502...89F.

- ↑ Erler, Theodore; Maccaferri, Carlo (2014). "String field theory solution for any open string background". Journal of High Energy Physics (Springer Nature) 2014 (10): 029. doi:10.1007/jhep10(2014)029. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2014JHEP...10..029E.

- ↑ Thorn, Charles B. (1989). "String field theory". Physics Reports (Elsevier BV) 175 (1–2): 1–101. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(89)90015-x. ISSN 0370-1573. Bibcode: 1989PhR...175....1T.

- ↑ Giddings, Steven B.; Martinec, Emil; Witten, Edward (1986). "Modular invariance in string field theory". Physics Letters B (Elsevier BV) 176 (3–4): 362–368. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(86)90179-6. ISSN 0370-2693. Bibcode: 1986PhLB..176..362G.

- ↑ Zwiebach, Barton (1991). "A proof that Witten's open string theory gives a single cover of moduli space". Communications in Mathematical Physics (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 142 (1): 193–216. doi:10.1007/bf02099176. ISSN 0010-3616. Bibcode: 1991CMaPh.142..193Z. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1104248494.

- ↑ Preitschopf, Christian R.; Thorn, Charles B.; Yost, Scott (1990). "Superstring field theory". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 337 (2): 363–433. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(90)90276-j. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1990NuPhB.337..363P. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/7241635.

- ↑ Aref'eva, I.Ya.; Medvedev, P.B.; Zubarev, A.P. (1990). "New representation for string field solves the consistency problem for open superstring field theory". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 341 (2): 464–498. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(90)90189-k. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1990NuPhB.341..464A.

- ↑ Erler, Theodore (2008-01-07). "Tachyon vacuum in cubic superstring field theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2008 (1): 013. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2008/01/013. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2008JHEP...01..013E.

- ↑ N. Berkovits, "Review of open superstring field theory", hep-th/0105230

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan (1995). "Super-Poincaré invariant superstring field theory". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 450 (1–2): 90–102. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(95)00259-u. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1995NuPhB.450...90B.

- ↑ Michishita, Yoji (2005-01-07). "A Covariant Action with a Constraint and Feynman Rules for Fermions in Open Superstring Field Theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2005 (1): 012. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2005/01/012. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2005JHEP...01..012M.

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan; Echevarria, Carlos Tello (2000). "Four-point amplitude from open superstring field theory". Physics Letters B (Elsevier BV) 478 (1–3): 343–350. doi:10.1016/s0370-2693(00)00246-x. ISSN 0370-2693. Bibcode: 2000PhLB..478..343B.

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan (2000-04-19). "The tachyon potential in open Neveu-Schwarz string field theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2000 (4): 022. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2000/04/022. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2000JHEP...04..022B.

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan; Sen, Ashoke; Zwiebach, Barton (2000). "Tachyon condensation in superstring field theory". Nuclear Physics B 587 (1–3): 147–178. doi:10.1016/s0550-3213(00)00501-0. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 2000NuPhB.587..147B.

- ↑ Erler, Theodore (2013). "Analytic solution for tachyon condensation in Berkovits' open superstring field theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2013 (11): 7. doi:10.1007/jhep11(2013)007. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2013JHEP...11..007E.

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan (2005-10-27). "Pure spinor formalism as an N= 2 topological string". Journal of High Energy Physics 2005 (10): 089. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2005/10/089. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2005JHEP...10..089B.

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan; Siegel, Warren (2009-11-05). "Regularizing cubic open Neveu-Schwarz string field theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2009 (11): 021. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2009/11/021. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2009JHEP...11..021B.

- ↑ Sonoda, Hidenori; Zwiebach, Barton (1990). "Covariant closed string theory cannot be cubic". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 336 (2): 185–221. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(90)90108-p. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1990NuPhB.336..185S.

- ↑ Saadi, Maha; Zwiebach, Barton (1989). "Closed string field theory from polyhedra". Annals of Physics (Elsevier BV) 192 (1): 213–227. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(89)90126-7. ISSN 0003-4916. Bibcode: 1989AnPhy.192..213S.

- ↑ Kugo, Taichiro; Suehiro, Kazuhiro (1990). "Nonpolynomial closed string field theory: Action and its gauge invariance". Nuclear Physics B (Elsevier BV) 337 (2): 434–466. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(90)90277-k. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1990NuPhB.337..434K.

- ↑ Zwiebach, Barton (1993). "Closed string field theory: Quantum action and the Batalin-Vilkovisky master equation". Nuclear Physics B 390 (1): 33–152. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(93)90388-6. ISSN 0550-3213. Bibcode: 1993NuPhB.390...33Z.

- ↑ Zwiebach, Barton (1990-12-30). "Quantum Closed Strings from Minimal Area". Modern Physics Letters A (World Scientific Pub Co Pte Lt) 05 (32): 2753–2762. doi:10.1142/s0217732390003218. ISSN 0217-7323. Bibcode: 1990MPLA....5.2753Z.

- ↑ Moeller, Nicolas (2007-03-12). "Closed bosonic string field theory at quintic order: five-tachyon contact term and dilaton theorem". Journal of High Energy Physics 2007 (3): 043. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2007/03/043. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2007JHEP...03..043M.

- ↑ Moeller, Nicolas (2007-09-26). "Closed bosonic string field theory at quintic order II: marginal deformations and effective potential". Journal of High Energy Physics 2007 (9): 118. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2007/09/118. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2007JHEP...09..118M.

- ↑ Berkovits, Nathan; Okawa, Yuji; Zwiebach, Barton (2004-11-16). "WZW-like Action for Heterotic String Field Theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2004 (11): 038. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2004/11/038. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2004JHEP...11..038B.

|

KSF

KSF