Timeline of fluid and continuum mechanics

Topic: Physics

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

Short description: None

This timeline describes the major developments, both experimental and theoretical understanding of fluid mechanics and continuum mechanics. This timeline includes developments in:

- Theoretical models of hydrostatics, hydrodynamics and aerodynamics.

- Hydraulics

- Elasticity

- Mechanical waves and acoustics

- Valves and fluidics

- Gas laws

- Turbulence modeling

- Plasticity and rheology

- Quantum fluids like Bose–Einstein condensates and superfluidity

- Microfluidics

Prehistory and antiquity

- Before 3000 BC – Civilization starts by settling around rivers, coast and lakes.

- 3000 BC – Irrigation techniques develop in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.[1] Indus Valley Civilisation develops city-wide drainage systems and toilet systems.[1] Egyptians develop reed boats.

- 2300 BC – Construction of the Nahrawan Canal.[1]

- 2000–1500 BC – First dams constructed in India to control water.[1]

- 1700 BC – Windmill are used in Babylonia to pump water.

- 14th century BC – Water clock are developed in Egypt under the reign of Amenhotep III. Clepsydra water clock design is developed in ancient Greece.[1]

- 6th century BC – Theodorus of Samos invents the water level. Ancient Rome's drainage system is designed during the reign of Tarquinius Priscus. Rome's Cloaca Maxima is constructed by lining a river bed with stone. Tunnel of Eupalinos is constructed in Samos.[1]

- 4th century BC – Mencius describes how to measure an elephant using displacement of water. Development of rain gauges in India.[1] Aqua Appia first Roman aqueduct is built in Rome.[1]

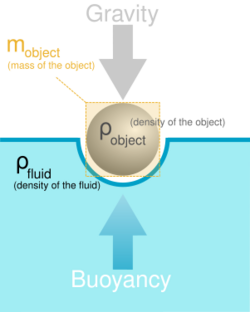

- 3rd century BC – Archimedes published On Floating Bodies describing the general principle for buoyancy and hydrostatics. Archimedes develops Archimedes' screw for water extraction.[1]

- 2nd century BC – The aqueduct Aqua Tepula and Aqua Marcia aqueducts are completed in Rome.[1] Zhang Heng of Han dynasty designs the first known seismoscope.[2][3][4]

- 1st century BC – Frontinus publishes his treatise De aquaeductu on Roman water engineering. Hero of Alexandria makes a series of experiments and devices with fluids, including the aeolipile steam device and wind harnessing devices.

Middle ages

- 8th–13th century – Arab Agricultural Revolution

- 725 – Northumbrian monk Bede publishes The Reckoning of Time, which includes a quantitative description of the influence of the moon and the sun over the tides.

- c. 850– Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi (Albumasar) publishes his Kitab al-madkhal al-kabir recording the Moon position and tides, he recognizes that there are two tides in day.[5]

- 850 – The Book of Ingenious Devices is published by the Banū Mūsā brothers, describing a number of early automatic controls using fluid mechanics.[6][7]

- 1206 – Ismail al-Jazari invented water-powered programmable automata/robots and water music devices.[8]

Renaissance

- 1432 – Portuguese develop caravels for long-distance ocean travel.[1]

- 1450 –Nicholas of Cusa publishes his experiments with fluids in Idiota de staticis experimentis, including the first proposal to measure air moisture using wool.

- 1480-1510 – Leonardo da Vinci develops the first sophisticated parachute, the first descriptions of capillary action, and the first turbine water wheels designs.[1]

- 1586 – Simon Stevin publishes De Beghinselen des Waterwichts ("Principles on the weight of water") on hydrostatics. He first details the hydrostatic paradox.[9]

- 1596 – Galileo Galilei produces the first (Galileo) thermometer.[1]

17th century

- 1619 – Benedetto Castelli published Della Misura dell'Acque Correnti ("On the Measurement of Running Waters"), one of the foundations of modern hydrodynamics.[10]

- 1619 – William Harvey provides first model of the human circulatory system.[1]

- 1624 – Jan Baptist van Helmont coins the term "gas".[1]

- 1631 – René Descartes first describes the principle of the mercury barometer.

- 1643 – Evangelista Torricelli provides a relation between the speed of fluid flowing from an orifice to the height of fluid above the opening, given by Torricelli's law. He also builds a mercury barometer and does a series of experiments on vacuum.[1]

- 1650 – Otto von Guericke invents the first vacuum pump.[1]

- 1653–1663 Blaise Pascal establishes Pascal's law of hydrostatics.

- 1662-1678 – Robert Boyle and Edme Mariotte independently discover a gas law that describes the relationship between pressure and volume given by Boyle's law (or Boyle-Mariotte's law).

- 1678 – Robert Hooke publishes Hooke's law describing linear deformation of a spring.

- 1687 – Isaac Newton publishes Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), introducing the Newton's laws of motion of classical mechanics.[11] He also introduces the concept of Newtonian fluid.

18th century

- 1713 – Antoine Parent introduces the concept of shear stress.[12]

- 1714 – Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit develops the mercury-in-glass thermometer along the Fahrenheit temperature scale.[1]

- 1718–1719 – James Jurin writes the law of capillary action, known as Jurin's law.

- 1727 – Leonhard Euler introduces linear elasticity and the Young's modulus.[12]

- 1732 – Henri Pitot discovers how to measure the pressure from the speed of a fluid using a Pitot tube.[13]

- 1738 – Daniel Bernoulli publishes Hydrodynamica discussing the mathematical relation between pressure and velocity of fluids according to Bernoulli's principle.[1]

- 1742 – Anders Celsius designs a thermometer with the Celsius scale.

- 1744 – Euler introduces the concept of deformation and strain.[12]

- 1747 – Jean le Rond d'Alembert's formula for the solutions of the wave equation in a string gets published.[14]

- 1752 – D'Alembert show an inconsistency of treating fluids as inviscid incompressible fluids, known as d'Alembert's paradox.

- 1757 – Euler introduces the Euler equations of fluid dynamics for incompressible and non-viscous flow. He also introduces the mathematical model for buckling.[12]

- 1764 – James Watt develops his steam water condenser leading to efficient steam engines.[1]

- 1765 – Jean-Charles de Borda experiments with whirling arm experiments. He corrects the available theories of air friction.[15]

- 1766 – de Borda publishes "Mémoire sur l'Écoulement des Fluides par les Orifices des Vases" on hydraulics and resistance of fluid through orifices. He comes up with Borda–Carnot equation.

- 1768 – Antoine de Chézy provides a semi-empirical formula for resistance of open channel flow, described by Chézy formula.[1]

- 1775 – Pierre-Simon Girard invents the water turbine.[1]

- 1776 – Charles Bossut, supervised by the Marquis de Condorcet and d'Alembert, publishes Nouvelles expériences sur la resistance de fluides, a report on a series experiments to test currents theories of hydraulics.

- 1775-76 – Pierre-Simon Laplace introduces the mathematical theory for tidal forces on oceans.[16]

- 1779 – Pierre-Louis-Georges du Buat publishes Principes de l'hydraulique ("Principles of hydraulics"), with semiempirical equations for the flow of water through pipes and open channels.[17][18]

- 1780 – Jacques Charles discover a gas law that describes the relationship between temperature and volume, given by Charles's law.

- 1782 – The Montgolfier brothers invent the hot air balloon.[1]

- 1785 – First theories of friction are introduced by Charles-Augustin de Coulomb.[19]

- 1787 – Ernst Chladni, publishes his experiments on vibrational modes of thin solid surfaces, describing the Chladni patterns created using a violin bow, based on previous experiments by Hooke.

- 1797 – Giovanni Battista Venturi discovers the Venturi effect.[20]

- 1799 – George Cayley introduces modern fixed wing-machines and identifies three important factors for flying machines: thrust, lift, drag, and weight.

19th century

- 1801 – Robert Fulton develops the first submarine.[1]

- 1805-1806 – The development of Young–Laplace equation by Thomas Young and improved by Laplace.[21]

- 1808-1809 – Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac describes the law of combining gases.

- 1811–1812 – Amedeo Avogadro and André-Marie Ampère independently discover a gas law relating volume and quantity of gas, given by Avogadro's law (or Avogadro-Ampère's law).

- 1821 – Claude-Louis Navier introduces viscosity in to Euler equations of fluids.

- 1821 – Sophie Germain wins a contest of the French Academy of Sciences for providing a partial theory for the vibration of an elastic surfaces.[22]

- 1827 – Augustin-Louis Cauchy introduces the Cauchy stress tensor and the concept of stress in elasticity.[23][12]

- 1827 – Robert Brown (botanist, born 1773), identifies the Brownian motion of pollen grains suspended in water.

- 1831– Michael Faraday first describes vibrational modes in liquids, known as Faraday waves.[24][25]

- 1831-1833– Thomas Graham first studies the diffusion in gases.[26]

- 1834 – Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron unifies many of the empirical gas laws into the ideal gas law.

- 1834 – John Scott Russell first describes the observation of solitary waves.

- 1837 – George Green find the minimal number of elastic moduli.[12]

- 1838-40 – Gotthilf Hagen and Jean Léonard Marie Poiseuille study laminar flow, independently establishing Hagen–Poiseuille equation.[1]

- 1841 – George Biddell Airy publishes the first correct formulation of Airy wave theory of water waves.[27]

- 1842 – Christian Doppler introduces the Doppler effect.

- 1842 – James Prescott Joule discovers magnetostriction, the first magnetomechanical effect.[28]

- 1842-1850 – Stokes completes the equations of motions of fluids, now referred as Navier–Stokes equations. He also extends Airy wave theory to non-linear Stokes wave theory.[29]

- 1852 – Heinrich Gustav Magnus describes the Magnus effect.[30][31]

- 1855 – Lord Kelvin calculates the thermodynamics work and energy due to elastic deformation.[12]

- 1855 – Adolf Eugen Fick publishes Fick's laws of diffusion.

- 1857 – Henry Darcy studies flow through porous media, leading to the discovery of Darcy's law.[32]

- 1857 – Rudolf Clausius introduces the first model for the kinetic theory of gases.[33]

- 1859 – W. H. Besant introduces an equation for the dynamics of bubbles in an incompressible fluid.[34]

- 1860 – James Clerk Maxwell introduces the Maxwell distribution of velocity of classical gas molecules.

- 1863 –Hermann von Helmholtz publishes Sensations of Tone on the physics of sound perception.

- 1864 – August Toepler invents Schlieren photography.

- 1865 – Lord Kelvin introduces the Kelvin material model for viscoelasticity.[35]

- 1856 – Carlo Marangoni studies the tears of wine, now explained by the Marangoni effect.

- 1867 – Helmholtz works on Helmholtz's theorems for vortex dynamics.

- 1867 – James Clerk Maxwell introduces the Maxwell material model for viscoelasticity.

- 1868–1871 – Helmholtz and Kelvin study and develop the theory of the Kelvin–Helmholtz instability.[36]

- 1870 – William Rankine develops an equation for the study of shock waves.

- 1871 – Francis Herbert Wenham designs and builds the first wind tunnel.[37][38]

- 1872-1877 – Joseph Valentin Boussinesq introduces the concept of turbulence in forms of eddy viscosity, as well as Boussinesq approximation for water waves and Boussinesq approximation for buoyancy.[1]

- 1873 – Johannes Diderik van der Waals introduces the Van der Waals equation.[39]

- 1883 – Osborne Reynolds demonstrates the transition and differences between laminar and turbulent pipe flow.[1]

- 1885 – Lord Rayleigh predicts the existence of Rayleigh surface waves.[40]

- 1885 – Helmholtz describes the concept of Helmholtz resonance.[41]

- 1887 – Pierre Henri Hugoniot based on the work of Rankine, introduces the Rankine–Hugoniot conditions to model shock waves.

- 1887 – First models of supersonic waves by Ernst Mach.[42] He introduces the concept of Mach number.

- 1888 – First commercial Venturi tube by Clemens Herschel.[43]

- 1888-1890 – Independently, Henry R. A. Mallock and Maurice Couette find the mathematical solution for the Couette flow.[44]

- 1889 – Robert Manning produces Manning's formula for open channel flow.[1]

- 1893 – Carl Barus develops the theory of the die swell in complex fluids.

- 1895 – Diederik Korteweg and Gustav de Vries (1895) rediscover the Korteweg–De Vries equation first treated by Boussinesq and introduce the idea of soliton solutions.[45][46]

20th century

- 1902 – Martin Kutta discusses the air flow through an airfoil using the Kutta condition.

- 1903 – The Wright brothers carry the first successful manned airplane flight.[1]

- 1903 – Walther Ritz introduces the Ritz method to study beam theory and Chladni figures.[47]

- 1905 – First theory of dislocations by Vito Volterra.

- 1905-1906 – First successful theories of Brownian motion by Albert Einstein and Marian Smoluchowski, supporting the atomic theory of matter.

- 1906 – Richard Dixon Oldham identifies the separate arrival of p-waves, s-waves and surface waves on seismograms and found the first clear evidence that the Earth has a central core.[48]

- 1908 – Paul Richard Heinrich Blasius introduces the concept of boundary layer.[1]

- 1908 – Experimental confirmation of the theories of Brownian motion by Jean Baptiste Perrin.

- 1910:

- Harry Fielding Reid put forward the elastic rebound theory for earthquakes.[49]

- Lord Rayleigh introduces the concept of Rayleigh flow.[50]

- Nikolay Zhukovsky introduces the Joukowsky transform and the Kutta–Joukowski theorem based on the work of Kutta.

- Carl Wilhelm Oseen solves the Stokes' paradox by introducing Oseen's approximation.[51]

- 1911 – Augustus Edward Hough Love predicts the existence of Love surface waves.[52]

- 1915–1916 – Frederick W. Lanchester comes up with the Lanchester's laws, a set of differential equations that were practical for flying combat.

- 1915-1917 – George Barker Jeffery[53] and Georg Hamel[54] introduce the equations of Jeffery–Hamel flow.

- 1916 – Horace Lamb coins the term "vorticity".[55]

- 1916 – Eugene C. Bingham studies Bingham plastics

- 1916-1923 – Lord Rayleigh, and later G. I. Taylor describe Rayleigh–Taylor instability.

- 1917 – Lamb introduces Lamb waves, generalizing Rayleigh's wave theory for thin metal plates.

- 1918 – Ludwig Prandtl develops theory of flow over airplane wings.[1]

- 1919 – Jacob Bjerknes established the bases the Norwegian cyclone model.[1]

- 1920 – Nikola Tesla patents the Tesla valve, opening the field of fluidics.[56]

- 1920 – Bingham coins the term rheology from a suggestion by a colleague, Markus Reiner.[57]

- 1921 – Theodore von Kármán introduces the turbulence model of Von Kármán swirling flow, and phenomena like Kármán vortex street.[58]

- 1921 – Alan Arnold Griffith develops his theory of fracture mechanics.[59]

- 1922 – Supersonic wind tunnel is invented in National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom).

- 1926 – Einstein solves the tea leaf paradox.

- 1925 – Jakob Ackeret publishes the theory of supersonic airfoils.

- 1926 – Erwin Madelung relates quantum mechanics with hydrodynamics through his quantum hydrodynamics equations, known as Madelung equations.

- 1931 – Sylvia Skan and Victor Montague Falkner introduce the equations for the Falkner–Skan boundary layer.[60]

- 1932 – The concept of quantum of sound (phonons) is introduced by Igor Tamm.

- 1937 – Superfluidity is discovered in helium-4 by Pyotr Kapitsa[61] and independently by John F. Allen and Don Misener.[62]

- 1938 – Philip Saffman and G. I. Taylor publish on Saffman–Taylor instability.[63]

- 1937 – Lev Landau introduces Landau theory of phase transitions.

- 1940-1941 – László Tisza and Landau introduce the two-fluid model for helium.

- 1941 – Landau introduces the concept of second sound in condensed matter.[64]

- 1942 – First magnetohydrodynamics descriptions of plasma by Hannes Alfvén. He also introduced the idea of Alfvén waves.[65][66]

- 1948 – Milton S. Plesset improves on Rayleigh and Bessant equations for the dynamics of bubbles by including surface tension according to Rayleigh–Plesset equation.[67]

- 1941 – Andrey Kolmogorov introduces his detailed theory of turbulence.

- 1947– Karl Weissenberg introduces the Weissenberg effect in non-Newtonian fluids.

- 1950 – James G. Oldroyd introduces the Oldroyd-B model of viscoelasticity.[68]

- 1944 – Lewis Ferry Moody plots Darcy–Weisbach friction factor against Reynolds number for various values of relative roughness, leading to the first Moody chart.[1]

- 1961 – Eugene P. Gross[69] and Lev Pitaevskii[70] introduce Gross–Pitaevskii equation for the condensation of bosons.

- 1963 – Alex Kaye describes the Kaye effect in viscoelastic liquids.

- 1972 – David Lee, Douglas Osheroff and Robert Coleman Richardson discovered two phase transitions of helium-3 along the melting curve, which were soon realized to be the two superfluid phases.

- 1990 – first micro total analysis system (μTAS) for microfluidics by Andreas Manz (fr).[71]

- 1995 – The first Bose–Einstein condensate is produced by Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman at the University of Colorado at Boulder NIST–JILA lab, in a gas of rubidium atoms cooled to 170 nanokelvins (nK).[72] Shortly thereafter, Wolfgang Ketterle at MIT produced a Bose–Einstein condensate in a gas of sodium atoms.

21st century

- c. 2000 – Development of droplet-based microfluidics.[73][74]

- 2003 – Deborah S. Jin and her collaboration produce the first fermionic condensate.[75]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 Rosentrater, Kurt; Balamuralikrishna, Radha (2005). "Essential highlights of the history of fluid mechanics". 2005 Annual Conference: 10–579. https://peer.asee.org/essential-highlights-of-the-history-of-fluid-mechanics.pdf.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1959). Science and Civilization in China, Volume 3: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 626–635. Bibcode: 1959scc3.book.....N.

- ↑ Dewey, James; Byerly, Perry (February 1969). "The early history of seismometry (to 1900)". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 59 (1): 183–227. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/topics/eqsci-history/early-seismometry.php.

- ↑ Agnew, Duncan Carr (2002). "History of seismology". International Handbook of Earthquake and Engineering Seismology. International Geophysics 81A: 3–11. doi:10.1016/S0074-6142(02)80203-0. ISBN 978-0-12-440652-0. Bibcode: 2002InGeo..81....3A.

- ↑ McMullin, Ernan (2002-02-01). "The Origins of the Field Concept in Physics" (in en). Physics in Perspective 4 (1): 13–39. doi:10.1007/s00016-002-8357-5. ISSN 1422-6944. Bibcode: 2002PhP.....4...13M. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00016-002-8357-5.

- ↑ Koetsier, Teun (2001), "On the prehistory of programmable machines: musical automata, looms, calculators", Mechanism and Machine Theory (Elsevier) 36 (5): 589–603, doi:10.1016/S0094-114X(01)00005-2.

- ↑ Kapur, Ajay; Carnegie, Dale; Murphy, Jim; Long, Jason (2017). "Loudspeakers Optional: A history of non-loudspeaker-based electroacoustic music". Organised Sound (Cambridge University Press) 22 (2): 195–205. doi:10.1017/S1355771817000103. ISSN 1355-7718.

- ↑ Professor Noel Sharkey, A 13th Century Programmable Robot (Archive), University of Sheffield.

- ↑ Gaukroger, Stephen; Schuster, John (2002-09-01). "The hydrostatic paradox and the origins of Cartesian dynamics". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 33 (3): 535–572. doi:10.1016/S0039-3681(02)00026-2. ISSN 0039-3681. Bibcode: 2002SHPSA..33..535G. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0039368102000262.

- ↑ "Benedetto Castelli - Biography" (in en). https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Castelli/.

- ↑ Newton, Isaac; Chittenden, N. W.; Motte, Andrew; Hill, Theodore Preston (1846). Newton's Principia: The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. University of California Libraries. Daniel Adee. http://archive.org/details/newtonspmathema00newtrich.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 "Mechanics of solids - Stress, Strain, Elasticity | Britannica" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/science/mechanics-of-solids/History.

- ↑ Anderson, John David (1998) (in en). A History of Aerodynamics: And Its Impact on Flying Machines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66955-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=1OeCJFJY3ZYC.

- ↑ D'Alembert (1747) "Recherches sur la courbe que forme une corde tenduë mise en vibration" (Researches on the curve that a tense cord [string] forms [when] set into vibration), Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles lettres de Berlin, vol. 3, pages 214-219. See also: D'Alembert (1747) "Suite des recherches sur la courbe que forme une corde tenduë mise en vibration" (Further researches on the curve that a tense cord forms [when] set into vibration), Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles lettres de Berlin, vol. 3, pages 220-249. See also: D'Alembert (1750) "Addition au mémoire sur la courbe que forme une corde tenduë mise en vibration," Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles lettres de Berlin, vol. 6, pages 355-360.

- ↑ "Early Developments in Aerodynamics". https://www.centennialofflight.net/essay/Theories_of_Flight/early_aero/TH3.htm.

- ↑ "Short notes on the Dynamical theory of Laplace". 20 November 2011. http://www.preservearticles.com/2011112017524/short-notes-on-the-dynamical-theory-of-laplace.html.

- ↑ Eckert, Michael (2021). "Pipe flow: a gateway to turbulence" (in en). Archive for History of Exact Sciences 75 (3): 249–282. doi:10.1007/s00407-020-00263-y. ISSN 0003-9519.

- ↑ Saint-Venant, Barré de (1866) (in fr). Notice sur la vie et les ouvrages de Pierre-Louis-Georges, comte Du Buat, colonel du génie... auteur des "Principes d'hydraulique". L. Danel. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb30059610j.

- ↑ Popova, Elena; Popov, Valentin L. (2015-06-01). "The research works of Coulomb and Amontons and generalized laws of friction" (in en). Friction 3 (2): 183–190. doi:10.1007/s40544-015-0074-6.

- ↑ Kent, Walter George (1912). An appreciation of two great workers in hydraulics; Giovanni Battista Venturi ... Clemens Herschel. University of California Libraries. London, Blades, East & Blades. http://archive.org/details/appreciationoftw00kentrich.

- ↑ Robert Finn (1999). "Capillary Surface Interfaces". AMS. http://www.ams.org/notices/199907/fea-finn.pdf.

- ↑ Case, Bettye Anne; Leggett, Anne M. (2005). Complexities: women in mathematics. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11462-0.

- ↑ Cauchy, Augustin (1827) (in French). Exercices de mathematiques. National Library of Naples. http://archive.org/details/bub_gb_o6hCzbAYX7cC.

- ↑ Faraday, M. (1831) "On a peculiar class of acoustical figures; and on certain forms assumed by a group of particles upon vibrating elastic surfaces", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (London), vol. 121, pp. 299–318. "Faraday waves" are discussed in an appendix to the article, "On the forms and states assumed by fluids in contact with vibrating elastic surfaces". This entire article is also available on-line (albeit without illustrations) at "Electronic Library" .

- ↑ Others who investigated "Faraday waves" include: (1) Ludwig Matthiessen (1868) "Akustische Versuche, die kleinsten Transversalwellen der Flüssigkeiten betreffend" (Acoustic experiments concerning the smallest transverse waves of liquids), Annalen der Physik, vol. 134, pp. 107–17; (2) Ludwig Matthiessen (1870) "Über die Transversalschwingungen tönender tropfbarer und elastischer Flüssigkeiten" (On the transverse vibrations of ringing low-viscosity and elastic liquids), Annalen der Physik, vol. 141, pp. 375–93; (3) John William Strutt (Lord Rayleigh) (1883), "On the crispations of fluid resting upon a vibrating support," Philosophical Magazine, vol. 16, pp. 50–58; (4) Thomas Brooke Benjamin and Fritz Joseph Ursell (1954), [1]"The stability of the plane free surface of a liquid in vertical periodic motion" Proceedings of the Royal Society A, vol. 225, issue 1163.

- ↑ Diffusion Processes, Thomas Graham Symposium, ed. J.N. Sherwood, A.V. Chadwick, W.M.Muir, F.L. Swinton, Gordon and Breach, London, 1971.

- ↑ Craik (2004).

- ↑ Lee, E W (1955-01-01). "Magnetostriction and Magnetomechanical Effects". Reports on Progress in Physics 18 (1): 184–229. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/18/1/305. Bibcode: 1955RPPh...18..184L. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0034-4885/18/1/305.

- ↑ Stokes (1847).

- ↑ G. Magnus (1852) "Über die Abweichung der Geschosse," Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, pages 1–23.

- ↑ G. Magnus (1853) "Über die Abweichung der Geschosse, und: Über eine abfallende Erscheinung bei rotierenden Körpern" (On the deviation of projectiles, and: On a sinking phenomenon among rotating bodies), Annalen der Physik, vol. 164, no. 1, pages 1–29.

- ↑ "Darcy's law | Groundwater Flow, Permeability & Hydraulics | Britannica" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/science/Darcys-Law.

- ↑ See:

- Maxwell, J.C. (1860 A): Illustrations of the dynamical theory of gases. Part I. On the motions and collisions of perfectly elastic spheres. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 4th Series, vol.19, pp.19-32. [2]

- Maxwell, J.C. (1860 B): Illustrations of the dynamical theory of gases. Part II. On the process of diffusion of two or more kinds of moving particles among one another. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 4th Ser., vol.20, pp.21-37. [3]

- ↑ Besant, W. H. (1859). "Article 158". A treatise on hydrostatics and hydrodynamics. Deighton, Bell. pp. 170–171. https://archive.org/details/atreatiseonhydr01besagoog/page/n182/mode/2up.

- ↑ "IV. On the elasticity and viscosity of metals" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 14: 289–297. 1865-12-31. doi:10.1098/rspl.1865.0052. ISSN 0370-1662. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspl.1865.0052.

- ↑ Matsuoka, Chihiro (2014). "Kelvin-Helmholtz Instability and Roll-up" (in en). Scholarpedia 9 (3). doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.11821. ISSN 1941-6016. Bibcode: 2014SchpJ...911821M.

- ↑ Wragg, David W. (1973). A Dictionary of Aviation (first ed.). Osprey. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-85045-163-4.

- ↑ Note:

- That Wenham and Browning were attempting to build a wind tunnel is briefly mentioned in: Sixth Annual Report of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain for the Year 1871, p. 6. From p. 6: "For this purpose [viz, accumulating experimental knowledge about the effects of wind pressure], the Society itself, through Mr. Wenham, had directed a machine to be constructed by Mr. Browning, who, he was sure, would take great interest in the work, and would give to it all the time and attention required."

- In 1872, the wind tunnel was demonstrated to the Aeronautical Society. See: Seventh Annual Report of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain for the Year 1872, pp. 6–12.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize in Physics 1910" (in en-US). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1910/waals/biographical/.

- ↑ [4] "On Waves Propagated along the Plane Surface of an ElasticSolid", Lord Rayleigh, 1885

- ↑ von Helmholtz, Hermann (1885). On the sensations of tone as a physiological basis for the theory of music (Second English ed.). London: Longmans, Green, and Co.. p. 44. https://archive.org/details/onsensationston00unkngoog. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ "Aerospaceweb.org | Ask Us - Ernst Mach and Mach Number". https://aerospaceweb.org/question/history/q0149.shtml.

- ↑ "Apparatus fro continuously measuring flow rate of fine material flowing through transport pipe". International Journal of Multiphase Flow 11 (6): I. 1985. doi:10.1016/0301-9322(85)90034-5. ISSN 0301-9322.

- ↑ Lueptow, Richard (2009-11-21). "Taylor-Couette flow" (in en). Scholarpedia 4 (11): 6389. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.6389. ISSN 1941-6016. Bibcode: 2009SchpJ...4.6389L.

- ↑ Korteweg, D. J.; de Vries, G. (May 1895). "XLI. On the change of form of long waves advancing in a rectangular canal, and on a new type of long stationary waves". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 39 (240): 422–443. doi:10.1080/14786449508620739. https://zenodo.org/record/1431215.

- ↑ Darrigol, O. (2005), Worlds of Flow: A History of Hydrodynamics from the Bernoullis to Prandtl, Oxford University Press, p. 84, ISBN 978-0-19-856843-8, https://archive.org/details/worldsofflowhist0000darr/page/84

- ↑ Leissa, A. W. (2005-11-04). "The historical bases of the Rayleigh and Ritz methods". Journal of Sound and Vibration 287 (4): 961–978. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2004.12.021. ISSN 0022-460X. Bibcode: 2005JSV...287..961L. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022460X05000362.

- ↑ "Oldham, Richard Dixon". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 10. Charles Scribner's Sons. 2008. p. 203.

- ↑ "Reid's Elastic Rebound Theory". United States Geological Survey. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/regional/nca/1906/18april/reid.php.

- ↑ Dover, ed (1964). Scientific papers of Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt). 5. pp. 573–610. https://archive.org/stream/scientificpapers05rayliala#page/n593/mode/2up.

- ↑ Batchelor, G. K. (2010). An Introduction to fluid dynamics. Cambridge mathematical library (14. print ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66396-0.

- ↑ A.E.H. Love, "Some problems of geodynamics", first published in 1911 by the Cambridge University Press and published again in 1967 by Dover, New York, USA.

- ↑ Jeffery, G. B. "L. The two-dimensional steady motion of a viscous fluid." The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 29.172 (1915): 455–465.

- ↑ Hamel, Georg. "Spiralförmige Bewegungen zäher Flüssigkeiten." Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung 25 (1917): 34–60.

- ↑ Truesdell, C. (1954). The kinematics of vorticity (Vol. 954). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- ↑ Adamatzky, Andrew (2019-06-10). "A brief history of liquid computers" (in en). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374 (1774). doi:10.1098/rstb.2018.0372. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 31006363.

- ↑ Steffe, James F. (1996). Rheological methods in food process engineering (2. ed.). East Lansing: Freeman Press. ISBN 978-0-9632036-1-8.

- ↑ Von Kármán, Theodore (1921). "Über laminare und turbulente Reibung". Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik 1 (4): 233–252. doi:10.1002/zamm.19210010401. Bibcode: 1921ZaMM....1..233K. https://zenodo.org/record/1447403.

- ↑ Griffith, A. A. (1921). "The Phenomena of Rupture and Flow in Solids". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 221 (582–593): 163–198. doi:10.1098/rsta.1921.0006. Bibcode: 1921RSPTA.221..163G.

- ↑ Hager, Willi (2014-03-21) (in en). Hydraulicians in Europe 1800-2000: Volume 2. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-5498-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=6EF9BgAAQBAJ&dq=V.+M.+Falkner&pg=PA1583.

- ↑ Kapitza, P. (1938). "Viscosity of Liquid Helium Below the λ-Point". Nature 141 (3558): 74. doi:10.1038/141074a0. Bibcode: 1938Natur.141...74K.

- ↑ Allen, J. F.; Misener, A. D. (1938). "Flow of Liquid Helium II". Nature 142 (3597): 643. doi:10.1038/142643a0. Bibcode: 1938Natur.142..643A.

- ↑ Homsy, G. M. (1987-01-01). "Viscous Fingering in Porous Media" (in en). Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 19: 271–311. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.19.010187.001415. ISSN 0066-4189. Bibcode: 1987AnRFM..19..271H. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.fl.19.010187.001415.

- ↑ Landau, L. (1941). Theory of the superfluidity of helium II. Physical Review, 60(4), 356.

- ↑ Alfvén, H (1942). "Existence of Electromagnetic-Hydrodynamic Waves". Nature 150 (3805): 405–406. doi:10.1038/150405d0. Bibcode: 1942Natur.150..405A.

- ↑ Fälthammar, Carl-Gunne (October 2007). "The discovery of magnetohydrodynamic waves". Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 69 (14): 1604–1608. doi:10.1016/j.jastp.2006.08.021. Bibcode: 2007JASTP..69.1604F.

- ↑ Brennen, Christopher E. (1995). Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509409-1.

- ↑ Oldroyd, J. G. (1950-02-22). "On the formulation of rheological equations of state" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 200 (1063): 523–541. doi:10.1098/rspa.1950.0035. ISSN 0080-4630. Bibcode: 1950RSPSA.200..523O. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspa.1950.0035.

- ↑ E. P. Gross (1961). "Structure of a quantized vortex in boson systems". Il Nuovo Cimento 20 (3): 454–457. doi:10.1007/BF02731494. Bibcode: 1961NCim...20..454G. https://cds.cern.ch/record/343403.

- ↑ L. P. Pitaevskii (1961). "Vortex lines in an imperfect Bose gas". Sov. Phys. JETP 13 (2): 451–454. http://www.jetp.ras.ru/cgi-bin/e/index/r/40/2/p646?a=list.

- ↑ Convery, Neil; Gadegaard, Nikolaj (2019-03-01). "30 years of microfluidics". Micro and Nano Engineering 2: 76–91. doi:10.1016/j.mne.2019.01.003. ISSN 2590-0072.

- ↑ Anderson, M. H.; Ensher, J. R.; Matthews, M. R.; Wieman, C. E.; Cornell, E. A. (1995-07-14). "Observation of Bose-Einstein Condensation in a Dilute Atomic Vapor" (in en). Science 269 (5221): 198–201. doi:10.1126/science.269.5221.198. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17789847. Bibcode: 1995Sci...269..198A.

- ↑ Delaquilla, Alessandra (2021-02-05). "History of Microfluidics" (in en). Elveflow. https://www.elveflow.com/microfluidic-reviews/general-microfluidics/history-of-microfluidics/.

- ↑ Ren, C.; Lee, A. (2020-11-27), Ren, Carolyn; Lee, Abraham, eds., "History and Current Status of Droplet Microfluidics" (in en), Droplet Microfluidics (The Royal Society of Chemistry): pp. 1–14, doi:10.1039/9781839162855-00001, ISBN 978-1-78801-769-5, https://books.rsc.org/books/book/864/chapter/626745/History-and-Current-Status-of-Droplet, retrieved 2025-09-19

- ↑ "A New Form of Matter: II, NASA-supported researchers have discovered a weird new phase of matter called fermionic condensates". Nasa Science. February 12, 2004. https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2004/12feb_fermi/.

|

Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 | Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Physics:Timeline_of_fluid_and_continuum_mechanics1 | ↧ Download this article as ZWI file

KSF

KSF