Eastern Himalaya

Topic: Place

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

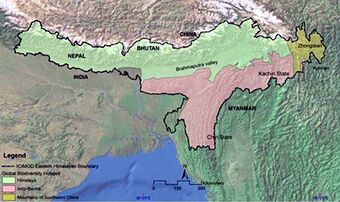

The Eastern Himalayas extend from eastern Nepal across Northeast India, Bhutan, the Tibet Autonomous Region to Yunnan in China and northern Myanmar. The climate of this region is influenced by the monsoon of South Asia from June to September.[1] It is a biodiversity hotspot, with notable biocultural diversity.[2][3]

Geologic strata

The Eastern Himalayas have a much more sophisticated geomorphic history and pervasive topographic features than the Central Himalayas. In the southwest of the Sub-Himalayas lies the Singalila Ridge, the western end of a group of uplands in Nepal. Most of the Sub-Himalayas are in Nepal; a small portion reaches into Sikkim, India and a fragment is in the southern half of Bhutan. The region's topography, in part, has facilitated the region's rich biological diversity and ecosystem structure.[3]

The Buxa range of Indo-Bhutan is also a part of the ancient rocks of the Himalayas. The ancient folds, running mainly along an east-west axis, were worn down during a long period of denudation lasting into cretaceous times, possibly over a hundred million years. During this time the carboniferous and permian rocks disappeared from the surface, except in its north near Hatisar in Bhutan and in the long trench extending from Jaldhaka River to Torsa River, where limestone and coal deposits are preserved in discontinuous basins. Limestone deposits also appear in Bhutan on the southern flanks of the Lower Himalayas. The rocks of the highlands are mainly sandstones of the Devonian age, with limestones and shales of the same period in places. The core of the mountain is exposed across the centre, where Paleozoic rocks, mainly Cambrian and Silurian slates and Takhstasang gneiss outcrops are visible in the northwest and northeast, the latter extending to western Arunachal Pradesh in India.

In the Mesozoic era the whole of the worn-down plateau was under sea. In this expansive shallow sea, which covered most of Assam and Bhutan, chalk deposits formed from seawater tides oscillating between land and sea levels. During subsequent periods, tertiary rocks were laid down. The Paro metamorphic belt may be found overlying Chasilakha-Soraya gneiss in some places. Silurian metamorphics in other places suggest long denudation of the surface. This was the time of Alpine mountain and large number of "active volcanoes" formation which act as backbone of the Himalayas and much of the movement in the palaeozoic region was probably connected with it. The Chomolhari tourmaline granites of Bhutan, stretching westwards from the Paro Chu and adds much depth below the present surface, were formed during this period of uplift, fracture and subsidence.

Climate

The climate of the Eastern Himalayas is of a tropical montane ecosystem. The tropical rainforest climate is hot and wet all year round, with no dry season in the foothills in Köppen Climate Classification System (Af), and chilly winters mainly on higher elevations. The hot season commences around the middle of April reaching its maximum temperature in June, and finishing by the end of August. The average summer temperature is generally 20 °C (68 °F). The average annual rainfall is 10,000 mm (390 inches). A significantly large amount of snowfall is rare, and it is uncommon even at higher elevations. This belt of Himalayas is wetter as it receive more rain than the drier Western Himalayas.

In the valleys of Rangeet, Teesta, and Chumbi most precipitation during winter takes the form of snowfall. Snow accumulation in the valleys greatly reduces the area's wintertime temperature. The northeast monsoon is the predominant feature of the Eastern Himalayan region's weather, while on the southern slopes cold season precipitation is more important.

Agriculture

Agricultural conditions vary throughout the region. In the highlands the soil is morainic, and the hill slopes are cut by the locals into successive steps or terraces only a few meters broad, thus preventing water run-off and allowing spring crops to thrive. The region's economy relied mostly on shifting cultivation agriculture, supplemented by hunting, fishing and barter trade. Agricultural does not produce sufficient yields to meet local needs. The region's economy remained stagnant and at subsistence levels for centuries due to the lack of capital, investor access, or entrepreneurial knowledge. Inhabitants also relied heavily on wild and semi-cultivated species for food and herbal medicines.[2]

Political divisions

The Eastern Himalayas consist of 6 distinct political/national territories:

- Nepali Himalaya (central, eastern and southern Nepal)

- Darjeeling Sub-Himalaya

- Sikkim (Indian) Himalaya

- Assam Sub-Himalaya

- Bhutan Himalaya

- Arunachal Pradesh Himalaya

- Garhwal/Kumaon Himalaya

Wildlife

The Eastern Himalayas sustain a diverse array of wildlife, including many rare species of fauna and flora.[3] Wildlife in Nepal includes snow leopard in its Himalayan region, and Indian rhinoceros, Asian elephant and water buffalo in the foothills of the Himalayas, making the country one of the world's greatest biodiversity hotspots. Three major river basins of Nepal, namely the Ghaghara, Gandaki River and Koshi River basins, feature dense forests and provide habitat for butterfly species and 8% of the world's bird species. Preserving this diverse wilderness is essential for the area's and the world's biodiversity. The area has many ecological projects intended to ensure the survival and growth of many species.[4]

The most diverse cloud forest is in India and China at 2,000–3,300 m (6,600–10,800 ft), and tropical rainforest on the lower slopes up to 900 m (3,000 ft) in the foothills. At higher elevations, wet páramo grasslands occur up to 4,500 m (14,800 ft)), and above this elevation snow and ice occupies the space. Asian black bear, Himalayan vulture, and pikas are common around higher elevations, and also on the Tibetan plateau. Arunachal macaque (Macaca arunachalensis) and Rhesus macaque (M. mulatta) live in the tropical cloud forests, alongside various sunbird and pheasant species. Himalayan high-elevation wetlands are also notable for their biodiversity.[3]

The picture seen right is of the national flower of Bhutan Meconopsis gakyidiana, commonly called the blue poppy. This flower was the source of an ecological mystery for nearly a century, due to its misclassification as Meconopsis grandis. In 2017, after three years of field work and taxonomic studies, its classification was corrected by Bhutanese and Japanese researchers. It was theorised this misclassification may have arisen due to the finding that some Himalayan flora readily hybridize with each other and produce viable seeds, causing wider morphological diversity.[citation needed]

See also

- Western Himalaya

- Indus-Yarlung suture zone

- Main Himalayan Thrust

- Lower Himalayan Range

- Ecology of the Himalayas

- Geology of the Himalaya

- Sivalik Hills

- Geography of Myanmar

- Indian Himalayan Region

- Jammu and Kashmir (union territory)

- Transhimalaya

- Indo-Gangetic Plain

References

- ↑ Shrestha, A.B.; Devkota, L.P. (2010). Climate change in the Eastern Himalayas: observed trends and model projections. Kathmandu, Nepal: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development. http://lib.icimod.org/record/26846/files/attachment_697.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 O'Neill, A.R.; Badola, H.K.; Dhyani, P.P.; Rana, S.K. (2017). "Integrating ethnobiological knowledge into biodiversity conservation in the Eastern Himalayas". Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 13 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/s13002-017-0148-9. PMID 28356115.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 O'Neill, A. R. (2019). "Evaluating high-altitude Ramsar wetlands in the Sikkim Eastern Himalayas". Global Ecology and Conservation 20: e00715. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00715.

- ↑ "Himalayas | Places | WWF". http://www.worldwildlife.org/places/eastern-himalayas.

External links

- Eastern Himalayas – World Wildlife Fund projects

KSF

KSF