The Khabur river, near Dūr-Katlimmu

Rojava

Topic: Place

From HandWiki - Reading time: 63 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 63 min

Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

| |

|---|---|

Emblema

| |

Areas under the region's administration | |

| Status | De facto autonomous region of Syria |

| Capital | Ayn Issa[1] [ ⚑ ] 36°23′7″N 38°51′34″E / 36.38528°N 38.85944°E |

| Largest city | Raqqa |

| Official languages | See languages |

| Government | Libertarian socialist federated semi-direct democracy |

• Co-Presidents | Îlham Ehmed[2]

Mansur Selum[3] |

• Co-Chairs | Amina Omar Riad Darar[4] |

| Legislature | Syrian Democratic Council |

| Autonomous region | |

• Transitional administration declared | 2013 |

• Cantons declare autonomy | January 2014 |

• Cantons declare federation | 17 March 2016 |

• New administration declared | 6 September 2018 |

| Area | |

• Total | 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi)[5] |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | ≈2,000,000[6] |

| Currency | Syrian pound ({{{currency code}}}) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Driving side | right |

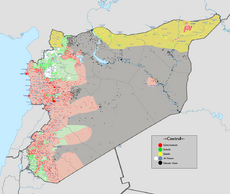

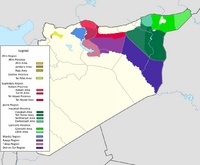

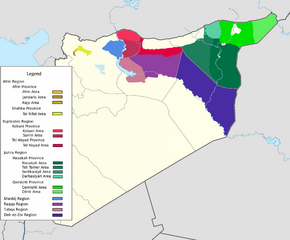

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES), also known as Rojava,[lower-alpha 1] is a de facto autonomous region in northeastern Syria.[12][13] It consists of self-governing sub-regions in the areas of Afrin, Jazira, Euphrates, Raqqa, Tabqa, Manbij and Deir Ez-Zor.[14][15][16] The region gained its de facto autonomy in 2012 in the context of the ongoing Rojava conflict and the wider Syrian Civil War, in which its official military force, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), has taken part.[17][18]

While entertaining some foreign relations, the region is not officially recognized as autonomous by the government of Syria or any international state or organization.[19][20] Northeastern Syria is polyethnic and home to sizeable ethnic Kurdish, Arab and Assyrian populations, with smaller communities of ethnic Turkmen, Armenians and Circassians.[21][22]

The supporters of the local authorities state that it is an officially secular polity[23][24][25] with direct democratic ambitions based on an anarchistic and libertarian socialist ideology promoting decentralization, gender equality,[26][27] environmental sustainability and pluralistic tolerance for religious, cultural and political diversity, and that these values are mirrored in its constitution, society, and politics, stating it to be a model for a federalized Syria as a whole, rather than outright independence.[28][29][30][31][32] The criticism against the region has included reports of authoritarianism,[33] Kurdification,[22][34][35] ban on critical journalists,[36][37] and influence from the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).[36]

Since 2016, Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian rebel forces have captured parts of Rojava through a series of military operations against the SDF.

Polity names and translations

Parts of Northern Syria are known as Western Kurdistan / West Kurdistan (Kurdish: Rojavayê Kurdistanê) or simply Rojava (/ˌroʊʒəˈvɑː/ ROH-zhə-VAH; Template:IPA-ku "the West"),[38][8][39] one of the four parts of Greater Kurdistan.[40] The name "Rojava" was thus associated with a Kurdish identity of the administration. As the region expanded and increasingly included areas dominated by non-Kurdish groups, most importantly Arabs, "Rojava" was used less and less by the administration in hopes of deethnicising its appearance and making it more acceptable to other ethnicities.[41] Regardless, the polity continued to be called "Rojava" by locals and international observers,[10][42][11][43] with journalist Metin Gurcan noting that "the concept of Rojava [had become] a brand gaining global recognition" by 2019.[42] The territory around Jazira province of northeastern Syria is called by Syriac-Assyrians as Gozarto (Classical Syriac: ܓܙܪܬܐ, romanized: Gozarto), part of the historical Assyrian homeland.[44] The area has also been nicknamed Federal Northern Syria, and the democratic confederalist autonomous areas of northern Syria.[8]

The first name of the local government for the Kurdish-dominated areas in Afrin District, Ayn al-Arab District (Kobanî), and northern al-Hasakah Governorate was Interim Transitional Administration, adopted in 2013.[8] After the three autonomus cantons were proclaimed in 2014,[45] PYD-governed territories were also nicknamed the Autonomous Regions[8] or Democratic Autonomous Administration.[46] On 17 March 2016, northern Syria's administration self-declared the establishment of a federal system of government as the Democratic Federation of Rojava – Northern Syria (Kurdish: Federaliya Demokratîk a Rojava – Bakurê Sûriyê; Arabic: الفدرالية الديمقراطية لروج آفا – شمال سوريا; Classical Syriac: ܦܕܪܐܠܝܘܬ݂ܐ ܕܝܡܩܪܐܛܝܬܐ ܠܓܙܪܬܐ ܒܓܪܒܝܐ ܕܣܘܪܝܐ, romanized: Federaloyotho Demoqraṭoyto l'Gozarto b'Garbyo d'Suriya; sometimes abbreviated as NSR).[8][47][48][49][50]

The updated December 2016 constitution of the polity uses the name Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (DFNS) (Kurdish: Federaliya Demokratîk a Bakûrê Sûriyê; Arabic: الفدرالية الديمقراطية لشمال سوريا; Classical Syriac: ܦܕܪܐܠܝܘܬ݂ܐ ܕܝܡܩܪܐܛܝܬܐ ܕܓܪܒܝ ܣܘܪܝܐ, romanized: Federaloyotho Demoqraṭoyto d'Garbay Suriya).[51][52][53][54]

Since 6 September 2018, the Syrian Democratic Council has adopted a new name for the region, naming it the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES) (Kurdish: Rêveberiya Xweser a Bakur û Rojhilatê Sûriyeyê; Arabic: الإدارة الذاتية لشمال وشرق سوريا; Classical Syriac: ܡܕܰܒܪܳܢܘܬ݂ܳܐ ܝܳܬ݂ܰܝܬܳܐ ܠܓܰܪܒܝܳܐ ܘܡܰܕܢܚܳܐ ܕܣܘܪܝܰܐ, romanized: Mdabronuṯo Yoṯayto l-Garbyo w-Madnḥyo d-Suriya; Turkish: Kuzey ve Doğu Suriye Özerk Yönetimi) also sometimes translated into English as the "Self-Administration of North and East Syria", encompassing the Euphrates, Afrin, and Jazira regions as well as the local civil councils in the regions of Raqqa, Manbij, Tabqa, and Deir ez-Zor.[55][1][56]

Geography

The region lies to the west of the Tigris along the Turkish border and borders Iraqi Kurdistan to the southeast. The region is at latitude approximately 36°30' north and mostly consists of plains and low hills, however there are some mountains in the region such as Mount Abdulaziz as well as the western part of the Sinjar Mountain Range in the Jazira Region.

In terms of governorates of Syria, the region is formed from parts of the al-Hasakah, Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor and the Aleppo governorates.

History

Background

Northern Syria is part of the Fertile Crescent, and includes archaeological sites dating to the Neolithic, such as Tell Halaf. In antiquity, the area was part of the Mitanni kingdom, its centre being the Khabur river valley in modern-day Jazira Region. It was then part of Assyria, with the last surviving Assyrian imperial records, from between 604 BC and 599 BC, were found in and around the Assyrian city of Dūr-Katlimmu.[57] Later it was ruled by different dynasties and empires - the Achaemenids of Iran, the Hellenes who succeeded Alexander the Great, the Artaxiads of Armenia,[58] Rome, the Iranian Parthians and[59] Sasanians,[60] then by the Byzantines and successive Arab Islamic caliphates.

Kurdish settlement in Syria goes back to before the Crusades of the 11th century. A number of Kurdish military and feudal settlements from before this period have been found in Syria. Such settlements have been found in the Alawite and north Lebanese mountains and around Hama and its surroundings. The Crusade fortress of Krak des Chevaliers, which is known in Arabic as Hisn al-Akrad (Castle of the Kurds), was originally a Kurdish military settlement before it was enlarged by the French Crusaders. Similarly, the Kurd-Dagh (Kurdish Mount) has been inhabited by Kurds for more than a millennium.[61]

During the Ottoman Empire (1516–1922), large Kurdish-speaking tribal groups both settled in and were deported to areas of northern Syria from Anatolia. The demographics of this area underwent a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century. Some Circassian, Kurdish and Chechen tribes cooperated with the Ottoman (Turkish) authorities in the massacres of Armenian and Assyrian Christians in Upper Mesopotamia, between 1914 and 1920, with further attacks on unarmed fleeing civilians conducted by local Arab militias.[62][63][64][65] Many Assyrians fled to Syria during the genocide and settled mainly in the Jazira area.[64][66][67] Starting in 1926, the region saw another immigration of Kurds following the failure of the Sheikh Said rebellion against the Turkish authorities.[68] While many of the Kurds in Syria have been there for centuries, waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in Syrian Al-Jazira Province, where they were granted citizenship by the French Mandate authorities.[69] The number of Turkish Kurds settled in al-Jazira province during the 1920s was estimated at 20,000 people, out of 100,000 inhabitants, with the remainder of the population being Christians (Syriac, Armenian, Assyrian) and Arabs.[70]

Rule from Damascus

Following Syria's independence, policies of Arab nationalism and attempts at forced Arabization became widespread in the country's north, to a large part directed against the Kurdish population.[71] The region received little investment or development from the central government and laws discriminated against Kurds owning property, driving cars, working in certain professions and forming political parties.[72] Property was routinely confiscated by government loansharks. After the Ba'ath Party seized power in the 1963 Syrian coup d'état, non-Arab languages were forbidden at Syrian public schools. This compromised the education of students belonging to minorities like Kurds, Turkmen, and Assyrians.[73][74] Some groups like Armenians, Circassians, and Assyrians were able to compensate by establishing private schools, but Kurdish private schools were also banned.[71][75] Northern Syrian hospitals lacked equipment for advanced treatment and instead patients had to be transferred outside the region. Numerous place names were arabized in the 1960s and 1970s.[74] In his report for the 12th session of the UN Human Rights Council titled Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights held that "Successive Syrian governments continued to adopt a policy of ethnic discrimination and national persecution against Kurds, completely depriving them of their national, democratic and human rights – an integral part of human existence. The government imposed ethnically-based programs, regulations and exclusionary measures on various aspects of Kurds’ lives – political, economic, social and cultural."[76] Kurdish cultural festivals like Newroz were effectively banned.[77]

In many instances, the Syrian government arbitrarily deprived ethnic Kurdish citizens of their citizenship. The largest such instance was a consequence of a census in 1962, which was conducted for exactly this purpose. 120,000 ethnic Kurdish citizens saw their citizenship arbitrarily taken away and became stateless.[71][77][78] This status was passed to the children of a "stateless" Kurdish father.[71] In 2010, the Human Rights Watch (HRW) estimated the number of such "stateless" Kurdish people in Syria at 300,000.[79][80] In 1973, the Syrian authorities confiscated 750 square kilometres (290 square miles) of fertile agricultural land in Al-Hasakah Governorate, which was owned and cultivated by tens of thousands of Kurdish citizens, and gave it to Arab families brought in from other provinces.[76][75] In 2007, in the Al-Hasakah Governorate, 600 square kilometres (230 square miles) around Al-Malikiyah were granted to Arab families, while tens of thousands of Kurdish inhabitants of the villages concerned were evicted.[76] These and other expropriations was part of the so-called "Arab Belt initiative" which aimed to change the demographic fabric of the resource-rich region.[71] Accordingly, relations between the Syrian government and the Syrian Kurdish population were tense.[81]

The response of northern Syrian parties and movements to the policies of Hafez al-Assad's Ba'athist government varied greatly. Some parties opted for resistance, whereas others such as the Kurdish Democratic Progressive Party[82] and the Assyrian Democratic Party[83] attempted to work within the system, hoping to bring about changes through soft pressure.[84] In general, parties that openly represented certain ethnic and religious minorities were not allowed to participate in elections, but their politicians were occasionally allowed to run as Independents.[85] Some Kurdish politicians won seats during the Syrian elections in 1990.[86] The government also recruited Kurdish officials, in particular as mayors, to ease ethnic relations. Regardless, northern Syrian ethnic groups remained deliberately underrepresented in the bureaucracy, and many Kurdish majority areas were run by Arab officials from other parts of the country.[85] Security and intelligence agencies worked hard to suppress dissidents, and most Kurdish parties remained underground movements. The government monitored, though generally allowed this "sub-state activity" because the northern minorities including the Kurds rarely caused unrest with the exception of the 2004 Qamishli riots.[85] The situation improved after the death of Hafez al-Assad and the election of his son, Bashar al-Assad, under whom the number of Kurdish officials grew.[87]

Despite the Ba'athist internal policies which officially suppressed a Kurdish identity, the Syrian government allowed the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) to set up training camps from 1980. The PKK was a militant Kurdish group led by Abdullah Öcalan which was waging an insurgency against Turkey. Syria and Turkey were hostile toward each other at the time, resulting in the use of the PKK as proxy group.[85][42] The party began to deeply influence the Syrian Kurdish population in the Afrin and Ayn al-Arab Districts, where it promoted Kurdish identity through music, clothing, popular culture, and social activities. In contrast, the PKK remained much less popular among Kurds in al-Hasakah Governorate, where other Kurdish parties maintained more influence. Many Syrian Kurds developed a long-lasting sympathy for the PKK, and a large number, possibly more than 10,000, joined its insurgency in Turkey.[85] A rapprochement between Syria and Turkey brought an end to this phase in 1998, when Öcalan and the PKK were formally expelled from northern Syria. Regardless, the PKK maintained a cladestine presence in the region.[85][42]

In 2002, the PKK and allied groups organized the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) to implement Öcalan's ideas in various Middle Eastern countries. A KCK branch was also set up in Syria, led by Sofi Nureddin and known as "KCK-Rojava". In an attempt to outwardly distance the Syrian branch from the PKK,[42] the Democratic Union Party (PYD) was established as de facto Syrian "successor" of the PKK in 2003.[85] The "People's Protection Units" (YPG), a paramilitary wing of the PYD, was also founded during this time, but remained dormant.[88]

Establishment of de facto autonomy and war against ISIL

In 2011, a civil uprising erupted in Syria, prompting hasty government reforms. One of the issues addressed during this time was the status of Syria's stateless Kurds, as President Bashar al-Assad granted about 220,000 Kurds citizenship.[87] In course of the next months, the crisis in Syria escalated into a civil war. The armed Syrian opposition seized control of several regions, while security forces were overstretched. In mid-2012 the government responded to this development by withdrawing its military from three mainly Kurdish areas[89][90] and leaving control to local militias. This has been described as an attempt by the Assad regime to keep the Kurdish population out of the initial civil uprising and civil war.[89]

Existing underground Kurdish political parties, namely the PYD and the Kurdish National Council (KNC), joined to form the Kurdish Supreme Committee (KSC) and the People's Protection Units (YPG) militia was reestablished to defend Kurdish-inhabited areas in northern Syria. In July 2012, the YPG established control in the towns of Kobanî, Amuda and Afrin, and the Kurdish Supreme Committee established a joint leadership council to administer the towns. Soon YPG also gained control of the cities of Al-Malikiyah, Ras al-Ayn, al-Darbasiyah, and al-Muabbada and parts of Hasakah and Qamishli.[91][92][93] Doing so, the YPG and its female wing, the Women's Protection Units (YPJ), mostly battled factions of the Free Syrian Army, and Islamist militias like the al-Nusra Front and Jabhat Ghuraba al-Sham. It also eclipsed rival Kurdish militias,[94][89] and absorbed some government loyalist groups.[95] According to researcher Charles R. Lister, the government's withdrawal and concurrent rise of the PYD "raised many eyebrows", as the relationship between the two entities was "highly contentious" at the time. The PYD was known to oppose certain government policies, but had also strongly criticised the Syrian opposition.[93]

The Kurdish Supreme Committee was dissolved in 2013, when the PYD abandoned the coalition with the KNC and established the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM) coalition.[96] On 19 July 2013, the PYD announced that it had written a constitution for an "autonomous Syrian Kurdish region", and planned to hold referendum to approve the constitution in October 2013. Qamishli served as first de facto capital of the PYD-led governing body,[7] which was official called the "Interim Transitional Administration".[8] The announcement was widely denounced by both moderate as well as Islamist factions of the Syrian opposition.[7] In January 2014, three areas under TEV-DEM rule declared their autonomy as cantons (now Afrin Region, Jazira Region and Euphrates Region) and an interim constitution was approved. The Syrian opposition and even the Kurdish parties belonging to the KNC condemned this move, regarding the canton system as illegal, authoritarian, and supportive of the Syrian government.[45] The PYD countered that the constitution was open to review and amendment, and that the KNC had been consulted on its drafting beforehand.[33] From September 2014 to spring 2015, the YPG forces in Kobanî Canton, supported by some Free Syrian Army militias and leftist international and Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) volunteers, fought and finally repelled an assault by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) during the Siege of Kobanî,[97] and in the YPG's Tell Abyad offensive of summer of 2015, the regions of Jazira and Kobanî were connected.[98]

After the YPG victory over ISIL in Kobanî in March 2015, an alliance between YPG and the United States was formed, which greatly worried Turkey, because Turkey stated the YPG was a clone of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) which Turkey (and the U.S. and the E.U.) designate as terrorists.[89] In December 2015, the Syrian Democratic Council was created. On 17 March 2016, at a TEV-DEM-organized conference in Rmelan the establishment the Democratic Federation of Rojava – Northern Syria was declared in the areas they controlled in Northern Syria.[99] The declaration was quickly denounced by both the Syrian government and the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces.[47]

In March 2016, Hediya Yousef and Mansur Selum were elected co-chairpersons for the executive committee to organise a constitution for the region, to replace the 2014 constitution.[3] Yousef said the decision to set up a federal government was in large part driven by the expansion of territories captured from Islamic State: "Now, after the liberation of many areas, it requires us to go to a wider and more comprehensive system that can embrace all the developments in the area, that will also give rights to all the groups to represent themselves and to form their own administrations."[100] In July 2016, a draft for the new constitution was presented, based on the principles of the 2014 constitution, mentioning all ethnic groups living in Northern Syria and addressing their cultural, political and linguistic rights.[101][102] The main political opposition to the constitution have been Kurdish nationalists, in particular the KNC, who have different ideological aspirations than the TEV-DEM coalition.[103] On 28 December 2016, after a meeting of the 151-member Syrian Democratic Council in Rmelan, a new constitution was resolved; despite objections by 12 Kurdish parties, the region was renamed the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, removing the name "Rojava".[104]

Turkish military operations and occupation

Turkey had been alarmed about the presence of PKK-related forces at its southern border since 2012, when the first YPG pockets appeared and grew concerned when the YPG entered into an alliance with the US to oppose ISIS forces in the region.[105] The Turkish government's refusal to allow aid to be sent to the YPG during the Siege of Kobanî and the resultant Kurdish riots led to the breakdown of the 2013–2015 peace process in July 2015. This led to the revival of an armed conflict between the PKK and Turkish forces. The YPG's mother organisation the PYD reportedly provided the PKK with militants, explosives, arms and ammunition according to the Turkish pro-government Daily Sabah.[106]

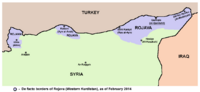

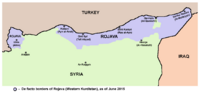

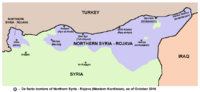

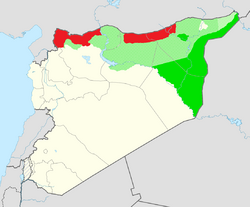

The first Turkish military operation against Rojava was Operation Euphrates Shield which began in August 2016. The objective of the operation was to prevent the YPG-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) from linking Afrin Canton (now Afrin Region) with the rest of Rojava and to capture Manbij from the SDF. Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian rebel forces were able to successfully prevent the linking of Rojava's cantons and captured all settlements in Jarabulus previously under the control of the SDF.[107] The operation also led to the handover of a part of the region to the Syrian government to act as a buffer zone against Turkey by the SDF.[108] Manbij was unable to be captured and remained under SDF control.

In early 2018 the second Turkish military operation against Rojava, Operation Olive Branch was launched alongside Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army with the intention of capturing the Kurdish-majority Afrin and to oust the YPG/SDF from region.[109] Afrin Canton, a subdivision of the region, was occupied and over 100,000 civilians were displaced and relocated to Afrin Region's Shahba Canton which remained under SDF, then joint SDF-Syrian Arab Army (SAA) control. The remaining forces of the SDF in the region has since launched an ongoing insurgency against the Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian rebel forces.[110]

The ongoing 2019 Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria, code-named by Turkey as Operation Peace Spring is the third Turkish military operation against Rojava conducted by Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian rebel forces against the SDF. The operation was launched on 9 October when the Turkish Air Force launched airstrikes on border towns.[111] Prior to the operation, on 6 October President Donald Trump had ordered American troops to withdraw from northeastern Syria where the United States had been providing support to the SDF.[112] Journalists called the withdrawal "a serious betrayal to the Kurds" as well as "a catastrophic blow to US credibility as an ally and Washington's standing on the world stage", with a journalist stating that "this was one of the worst US foreign policy disasters since the Iraq War".[113][114][115][116] Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian rebel forces captured 68 settlements, including Ras al-Ayn, Tell Abyad, Suluk, Mabrouka and Manajir during the 9-day operation before a 120-hour ceasefire was announced.[117][118][119][120][121] The operation was condemned by the international community[122] and human rights violations by Turkish forces were also reported.[123] Turkish president Erdoğan had for months warned that the continued presence of the YPG on the Turkish-Syrian border despite the Northern Syria Buffer Zone was unacceptable. The launch of the operation was thus labelled as "no surprise" by media outlets.[89] As unintended consequence of the Turkish operation, the worldwide popularity and legitimacy of the northeastern Syrian administration, grew, and several PYD and YPG representatives became internationally well known to an unprecedented degree. These events caused tensions within the KCK, however, as differences between the PKK and PYD leadership emerged. The northeastern Syrian administration took a "hawkish line" in opposition to the Turkish offensive, determined to maintain the regional autonomy and hoping for a continued alliance with the United States. In contrast, the PKK central command had become willing to restart negotiations with Turkey, distrusted the United States, and regarded the international success of its leftist ideology as more important than the survival of Rojava as administrative entity.[42]

Politics

The political system of the region is based on its adopted constitution, officially titled "Charter of the Social Contract".[29][124] The constitution was ratified on 9 January 2014; it provides that all residents of the region shall enjoy fundamental rights such as gender equality and freedom of religion.[29] It also provides for property rights.[125] The region's system of community government has direct democratic aspirations.[126]

A September 2015 report in The New York Times observed:[29]

"For a former diplomat like me, I found it confusing: I kept looking for a hierarchy, the singular leader, or signs of a government line, when, in fact, there was none; there were just groups. There was none of that stifling obedience to the party, or the obsequious deference to the "big man"—a form of government all too evident just across the borders, in Turkey to the north, and the Kurdish regional government of Iraq to the south. The confident assertiveness of young people was striking.

However, a 2016 paper from Chatham House[36] stated that power is heavily centralized in the hands of the Democratic Union Party (PYD). Abdullah Öcalan, a Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) leader imprisoned in İmralı, Turkey, has become an iconic figure in the region whose libertarian socialist ideology has shaped the region's society and politics through the ruling TEV-DEM coalition, a political alliance including the PYD and a number of smaller parties. Before TEV-DEM, the region was governed by the Kurdish Supreme Committee, a coalition of the PYD and the Kurdish National Council (KNC), which was dissolved by the PYD in 2013.[127][128][29][129] Besides the parties represented in TEV-DEM and the KNC, several other political groups operate in northern Syria. Several of these, such as the Kurdish National Alliance in Syria,[130][131] the Democratic Conservative Party,[132] the Assyrian Democratic Party,[133] and others actively participate in governing the region.

The politics of the region has been described as having "libertarian transnational aspirations" influenced by the PKK's shift toward anarchism, but also includes various "tribal, ethno-sectarian, capitalist and patriarchal structures."[125] The region has a "co-governance" policy in which each position at each level of government in the region includes a "female equivalent of equal authority" to a male.[134] Similarly, there are aspirations for equal political representation of all ethno-religious components – Arabs, Kurds and Assyrians being the most sizeable ones. This has been compared this to the Lebanese confessionalist system, which is based on that country's major religions.[125][135][136][137][136]

The PYD-led rule has triggered protests in various areas since they first captured territory. In 2019, residents of tens of villages in the eastern Deir ez-Zor Governorate demonstrated for two weeks, regarding the new regional leadership as Kurdish-dominated and non-inclusive, citing arrests of suspected ISIL members, looting of oil, lack of infrastructure as well as forced conscription into the SDF as reasons. The protests resulted in deaths and injuries.[138] It has been stated that the new political structures created in the region have been based on top-down structures, which have placed obstacles for the return of refugees, created dissent as well as a lack of trust between the SDF and the local population.[139]

Qamishli initially served as the de facto capital of the administration,[7][101] but the area's governing body later relocated to Ayn Issa.[1]

Administrative divisions

Article 8 of the 2014 constitution stipulates that "All Cantons in the autonomous regions are founded on the principle of local self-government. Cantons may freely elect their representatives and representative bodies, and may pursue their rights insofar as it does not contravene the articles of the Charter."[124]

The cantons were later reorganized into regions with subordinate cantons/provinces, areas, districts and communes. The first communal elections in the region were held on 22 September 2017. 12,421 candidates competed for around 3,700 communal positions during the elections, which were organized by the region's High Electoral Commission.[140][141] Elections for the councils of the Jazira Region, Euphrates Region and Afrin Region were held in December 2017.[15] Most of Afrin Region was occupied by Turkish-led forces in early 2018, though the administrative division continued to operate from Tell Rifaat which is under joint YPG-Syrian Army control.[55][142][143]

On 6 September 2018, during a meeting of the Syrian Democratic Council in Ayn Issa, a new name for the region was adopted, the "Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria", encompassing the Euphrates, Afrin, and Jazira regions as well as the local civil councils in the regions of Raqqa, Manbij, Tabqa, and Deir ez-Zor. During the meeting, a 70-member "General Council for the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria" was formed.[55][1][56]

| Regions | Official name (languages) | Prime Ministers | Deputy Prime Ministers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jazira Region | Template:Vunblist | Akram Hesso | Elizabeth Gawrie Hussein Taza Al Azam | |

| Euphrates Region | Template:Vunblist | Enver Muslim | Bêrîvan Hesen Xalid Birgil | |

| Afrin Region (in exile) |

Template:Vunblist | Hêvî Îbrahîm | Remzi Şêxmus Ebdil Hemid Mistefa | |

| Raqqa Region | Template:Vunblist | N/A | N/A | |

| Tabqa Region | Template:Vunblist | N/A | N/A | |

| Manbij Region | Template:Vunblist | N/A | N/A | |

| Deir ez-Zor Region | Template:Vunblist | N/A | N/A | |

Legislature

In December 2015, during a meeting of the region's representatives in Al-Malikiyah, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) was established to serve as the political representative of the Syrian Democratic Forces.[144] The co-leaders selected to lead the SDC at its founding were prominent human rights activist Haytham Manna and TEV-DEM Executive Board member Îlham Ehmed.[145][146] The SDC appoints an Executive Council which deal with the economy, agriculture, natural resources, and foreign affairs.[147] General elections were planned for 2014 and 2018,[147] but this was postponed due to fighting.

Education, media, and culture

School

Under the rule of the Ba'ath Party, school education consisted of only Arabic language public schools, supplemented by Assyrian private confessional schools.[148] In 2015, the region's administration introduced primary education in the native language (either Kurdish or Arabic) and mandatory bilingual education (Kurdish and Arabic) for public schools,[149][150][151] with English as a mandatory third language.[152] There are ongoing disagreements and negotiations over curriculums with the Syrian central government,[153][154] which generally still pays the teachers in public schools.[149][155][156][157]

In August 2016, the Ourhi Centre was founded by the Assyrian community in the city of Qamishli, to educate teachers in order to make Syriac-Aramaic an additional language in public schools in Jazira Region,[158] which then started in the 2016/17 academic year.[154] According to the region's Education Committee, in 2016/2017 "three curriculums have replaced the old one, to include teaching in three languages: Kurdish, Arabic and Syriac."[159] In August 2017 Galenos Yousef Issa of the Ourhi Centre announced that the Syriac curriculum would be expanded to grade 6, which earlier had been limited to grade 3, with teachers being assigned to Syriac schools in Al-Hasakah, Al-Qahtaniyah and Al-Malikiyah.[160][161] At the start of the academic year 2018–2019, the curricula in Kurdish and Arabic had been expanded to grades 1–12 and Syriac to grades 1–9. "Jineology" classes had also been introduced.[162] In general, schools are encouraged to teach the administration's "uptopian doctrine" which promotes diversity, democracy, and the ideas of Abdullah Öcalan.[26][163] Local reactions to the changes to the school system and curriculum were mixed. While many praised the new system because it encouraged tolerance and allowed Kurds and other minorities to be taught in their own languages,[26] others have criticised it as de facto compulsory indoctrination.[164]

The federal, regional and local administrations in the region put much emphasis on promoting libraries and educational centers, to facilitate learning and social and artistic activities. Examples are the Nahawand Center for Developing Children's Talents in Amuda (est. 2015) and the Rodî û Perwîn Library in Kobani (May 2016).[165]

For Assyrian private confessional schools there had at first been no changes.[154][166] However, in August 2018 it was reported that the region's authorities was trying to implement its own Syriac curriculum in private Christian schools that have been continuing to use an Arabic curriculum with limited Syriac classes approved by the Assad regime and originally developed by Syrian Education Ministry in cooperation with Christian clergy in the 1950s. The threatening of the closure of schools not complying with this resulted in protests erupting in Qamishli.[167][168][169] A deal was later reached in September 2018 between the region's authorities and the local Syriac Orthodox archbishopric, where the two first grades in these schools would learn the region's Syriac curriculum and grades three to six would continue to learn the Damascus approved curriculum.[170][171]

Higher education

While there was no institution of tertiary education on the territory of the region at the onset of the Syrian Civil War, an increasing number of such institutions have been established by the regional administrations in the region since.

- In September 2014, the Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy in Qamishli started classes.[29] More such academies designed under a libertarian socialist academic philosophy and concept are in the process of founding or planning.[172]

- In August 2015, the traditionally-designed University of Afrin in Afrin started teaching, with initial programs in literature, engineering and economics, including institutes for medicine, topographic engineering, music and theater, business administration and the Kurdish language.[173]

- In July 2016, Jazira Canton Board of Education started the University of Rojava in Qamishli, with faculties for Medicine, Engineering, Sciences, and Arts and Humanities. Programs taught include health, oil, computer and agricultural engineering; physics, chemistry, history, psychology, geography, mathematics and primary school teaching and Kurdish literature.[165][174] Its language of instruction is Kurdish, and with an agreement with Paris 8 University in France for cooperation, the university opened registration for students in the academic year 2016–2017.[175]

- In August 2016 Jazira Canton police forces took control of the remaining parts of Hasakah city, which included the Hasakah campus of the Arabic-language Al-Furat University, and with mutual agreement the institution continues to be operated under the authority of the Damascus government's Ministry of Higher Education.

Media

Incorporating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as other internationally recognized human rights conventions, the 2014 Constitution of North and East Syria guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of the press. As a result, a diverse media landscape has developed in the region,[176][177] in each of the Kurdish, Arabic, Syriac-Aramaic and Turkish languages of the land, as well as in English, and media outlets frequently use more than one language. Among the most prominent media in the region are Hawar News Agency and ARA News agencies and websites as well as TV outlets Rojava Kurdistan TV, Ronahî TV, and the bimonthly magazine Nudem. A landscape of local newspapers and radio stations has developed. However, media agencies often face economic pressure, as was demonstrated by the closure of news website Welati in May 2016.[178] In addition, the autonomous regions have imposed some limits on press freedom, for example forcing the press to get work permits. These can be cancelled, thereby curtailing the ability of certain press agencies to operate. However, the extent of these restricions differed greatly from area to area. By 2016, Kobani Canton was the least restrictive, followed by Jazira Canton which closely monitored and occasionally regulated press activity.[179] Afrin Canton was the most restrictive, and many local reporters operated anonymously.[180]

Political extremism in the context of the Syrian Civil War can put media outlets under pressure; for example in April 2016 the premises of Arta FM ("the first, and only, independent radio station staffed and broadcast by Syrians inside Syria") in Amuda was threatened and burned down by unidentified assailants.[181][182] During the Turkish military operation in Afrin, the KDP-affiliated Iraqi Kurdish Rudaw Media Network was also banned from reporting in the region.[183] On 2 September 2019, the Iraqi Kurdistan-based and KDP-affiliated Kurdistan 24 network was banned and had its offices seized by Rojava authorities, over a reported insult made by the network against Kurdistan Communities Union co-chair Bese Kozat.[184][185]

International media and journalists operate with few restrictions in the region, one of the only regions in Syria where they can operate with some degree of freedom.[177] This has led to several international media reports regarding the region, including major TV documentaries like BBC documentary (2014): Rojava: Syria's Secret Revolution or Sky1 documentary (2016): Rojava – The Fight Against ISIS.

Internet connections in the region are often slow due to inadequate infrastructure. Internet lines are operated by Syrian Telecom, which as of January 2017 is working on a major extension of the fibre optic cable network in southern Jazira Region.[186]

The arts

After the establishment of the de facto autonomous region, the Center of Art and Democratic Culture, located in Jazira Region, has become a venue for aspiring artists who showcase their work.[187][188] Among major cultural events in the region is the annual Festival of Theater in March/April as well as the Rojava Short Story Festival in June, both in the city of Qamishli, and the Afrin Short Film Festival in April.[189]

Economy

The Jazira Region is a major wheat and cotton producer and has a considerable oil industry. The Euphrates Region suffered most destruction of the three regions and has huge challenges in reconstruction, and has recently seen some greenhouse agriculture construction. The Afrin Region has had a traditional specialization on olive oil including Aleppo soap made from it, and had drawn much industrial production from the nearby city of Aleppo due to the fighting in Aleppo city from 2012-2016. Price controls are managed by local committees, which can set the price of basic goods such as food and medical goods.[190]

It has been theorized that the Assad government had deliberately underdeveloped parts of Northern Syria for the purposes of Arabization of the region as well as making secession attempts less likely.[191] During the Syrian Civil War, the infrastructure of the region has on average experienced less destruction than other parts of Syria. In May 2016, Ahmed Yousef, head of the Economic Body and chairman of Afrin University, stated that at the time, the economic output of the region (including agriculture, industry and oil) accounted for about 55% of Syria's gross domestic product.[192] In 2014, the Syrian government was still paying some state employees,[193] but fewer than before.[194] The administration of the region has however stated that "none of our projects are financed by the regime".[195]

There were at first no direct or indirect taxes on people or businesses in the region; the administration raised money mainly through tariffs and selling oil and other natural resources.[196][190] However, in July 2017, it was reported that the administration in the Jazira Region had started to collect income tax to provide for public services in the region.[197] In May 2016, The Wall Street Journal reported that traders in Syria experience the region as "the one place where they aren't forced to pay bribes."[198]

The main sources of revenue for the autonomous region have been presented as: 1. Income from public properties such as grain silos as well as from oil and gas in the Jazira Region, 2. Income from local taxation and customs fees taken at the border crossings, 3. Income from service delivery, 4. Finances sent from expats in Iraq and Turkey and 5. Local donations. In 2015 the autonomous administration of the region shared information regarding the region's finances in which the total amount of revenue for the year of 2014 for the autonomous administration was about 3 billion Syrian Pounds (≈5.8 million USD) from which 50% was spent on "self-defense and protection", 18% for the Jazira Canton (now Jazira Region), 8.5% for the Kobani Canton (now Euphrates Region), 8.5% for the Afrin Canton (now Afrin Region), 15% for the "Internal Committee" and any remainder as a reserve for use in the following year.[46]

External economic relations

Oil and food production is substantial,[147] so they are important exports. Agricultural products include sheep, grain and cotton. Important imports are consumer goods and auto parts.[199] Trade with Turkey and access to humanitarian and military aid is difficult due to a blockade by Turkey.[200] Turkey does not allow businesspeople or goods to cross its border.[201] The blockade from adjacent territories held by Turkey and ISIL, and partially also the KRG, temporarily caused heavy distortions of relative prices in Jazira Region and Euphrates Region (while separate, Afrin Region borders government-controlled territory since February 2016); for example in Jazira Region and Euphrates Region, through 2016 petrol cost only half as much as bottled water.[202]

The Semalka Border Crossing with Iraqi Kurdistan had been intermittently closed by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), but has been open permanently since June 2016,[203][203][204] and along with the establishment of a corridor to Syrian government controlled territory in April 2017,[205] economic exchange has increasingly normalized. Further, in May 2017 in northern Iraq, the Popular Mobilization Forces fighting ISIL cleared a corridor connecting the autonomous region and Iraqi government-controlled territory.[206][207][208]

Economy policy framework

The autonomous region is ruled by a coalition which bases its policy ambitions to a large extent on the libertarian socialist ideology of Abdullah Öcalan and have been described as pursuing a model of economy that blends co-operative and private enterprise.[209] In 2012, the PYD launched what it called the "Social Economy Plan", later renamed the "People's Economy Plan" (PEP).[210] Private property and entrepreneurship are protected under the principle of "ownership by use". Dr. Dara Kurdaxi, a regional official, has stated: "The method in Rojava is not so much against private property, but rather has the goal of putting private property in the service of all the peoples who live in Rojava."[211] Communes and co-operatives have been established to provide essentials.[212] Co-operatives account for a large proportion of agricultural production and are active in construction, factories, energy production, livestock, pistachio and roasted seeds, and public markets.[209] Several hundred instances of collective farming have occurred across towns and villages in the region, with communes consisting of approximately 20–35 people.[213] According to the region's "Ministry of Economics", approximately three quarters of all property has been placed under community ownership and a third of production has been transferred to direct management by workers' councils.[214]

Law and security

Legal system

Syrian civil laws are valid in the region if they do not conflict with the Constitution of the autonomous region. One example for amendment is personal status law, which in Syria is based on Sharia[215] and applied by Sharia Courts,[216] while the secular autonomous region proclaims absolute equality of women under the law, allowing civil marriage and banning forced marriage, polygamy[217][218] and underage marriage.[219][24]

A new criminal justice approach was implemented that emphasizes restoration over retribution.[220] The death penalty was abolished.[221] Prisons house mostly people charged with terrorist activity related to ISIL and other extremist groups.[222] A September 2015 report of Amnesty International stated that 400 people were incarcerated by the region's authorities and criticized deficiencies in due process of the judicial system of the region.[223][29][224]

The justice system in the region is influenced by Abdullah Öcalan's libertarian socialist ideology. At the local level, citizens create Peace and Consensus Committees, which make group decisions on minor criminal cases and disputes as well as in separate committees resolve issues of specific concern to women's rights like domestic violence and marriage. At the regional level, citizens (who need not be trained jurists) are elected by the regional People's Councils to serve on seven-member People's Courts. At the next level are four Appeals Courts, composed of trained jurists. The court of last resort is the Regional Court, which serves the region as a whole. Separate from this system, the Constitutional Court renders decisions on compatibility of acts of government and legal proceedings with the constitution of the region (called the Social Contract).[221]

Policing and security

Policing in the region is performed by the Asayish armed formation. Asayish was established on 25 July 2013 to fill the gap of security when the Syrian security forces withdrew.[225] Under the Constitution of North and East Syria, policing is a competence of the regions. The Asayish forces of the regions are composed of 26 official bureaus that aim to provide security and solutions to social problems. The six main units of Asayish are Checkpoints Administration, Anti-Terror Forces Command (HAT), Intelligence Directorate, Organized Crime Directorate, Traffic Directorate and Treasury Directorate. 218 Asayish centers were established and 385 checkpoints with 10 Asayish members in each checkpoint were set up. 105 Asayish offices provide security against ISIL on the frontlines across Northern Syria. Larger cities have general directorates responsible for all aspects of security including road controls. Each region has a HAT command, and each Asayish center organizes itself autonomously.[225]

Throughout the region, the municipal Civilian Defense Forces (HPC)[226] and the regional Self-Defense Forces (HXP)[227] also serve local-level security. In Jazira Region, the Asayish are further complemented by the Assyrian Sutoro police force, which is organized in every area with Assyrian population, provides security and solutions to social problems in collaboration with other Asayish units.[225] The Khabour Guards and Nattoreh, though not police units, also have a presence in the area, providing security in towns along the Khabur River. The Bethnahrain Women's Protection Forces also maintain a police branch. In the areas taken from ISIL during the Raqqa campaign, the Raqqa Internal Security Forces and Manbij Internal Security Forces operate as police forces. Deir ez-Zor also maintain an Internal Security Forces unit.

Militias

The main military force of the region is the Syrian Democratic Forces, an alliance of Syrian rebel groups formed in 2015. The SDF is led by the Kurdish majority People's Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, YPG). The YPG was founded by the PYD after the 2004 Qamishli clashes, but was first active in the Syrian Civil War.[228] There is also the Syriac Military Council (MFS), an Assyrian militia associated with the Syriac Union Party. There are also Free Syrian Army groups in the alliance such as Jaysh al-Thuwar and the Northern Democratic Brigade, tribal militias like the Arab Al-Sanadid Forces, and municipal military councils in the Shahba region, like the Manbij Military Council, the Al-Bab Military Council or the Jarablus Military Council.

The Self-Defence Forces (HXP) is a territorial defense militia and the only conscript armed force in the region. HXP is locally recruited to garrison their municipal area and is under the responsibility and command of the respective regions of the NES. Occasionally, HXP units have supported the YPG, and SDF in general, during combat operations against ISIL outside their own municipality and region.

Human rights

In the course of the Syrian Civil War, including 2014 and 2015 reports by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International stated that militias associated with the autonomous region were committing war crimes, in particular members of the People's Protection Units (YPG), Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International operate freely in the region.[229][230] The reports from 2014 include reports of arbitrary arrests and torture, other reports include the use of child soldiers.[231][232][233][234] In October 2015 the YPG demobilized 21 minors from the military service in its ranks.[235] Reports have been comprehensively debated and contested by both the YPG and other human rights organizations.[236][237] YPG members since September 2015 receive human rights training from Geneva Call and other international organizations.[238]

The region's civil government has been hailed in international media for human rights advancement in particular in the legal system, concerning women's rights, ethnic minority rights, freedom of Speech and Press and for hosting inbound refugees.[239][240][241][242] The political agenda of "trying to break the honor-based religious and tribal rules that confine women" is controversial in conservative quarters of society.[219] Enforcing conscription into the Self-Defence Forces (HXP) has been called a human rights violation from the perspective of those who call the region's institutions as illegitimate.[243]

Some persistent issues under the region's administration concern ethnic minority rights. One issue of contention is the consequence of the Baathist Syrian government's settling of Arab tribal settlers, expropriated for the purpose from its previous Kurdish owners in 1973 and 2007,[76][71][75] There have been calls to expel the settlers and return the land to their previous owners, which has led the political leadership of the region to press the Syrian government for a comprehensive solution.[244]

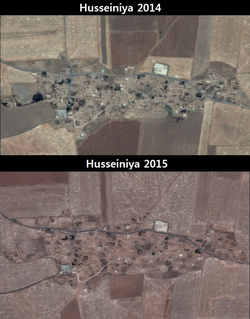

During the ongoing Syrian Civil War, organizations such as the Turkish government,[245] Amnesty International[246] and the Middle East Observer[247][248] have stated that SDF was forcibly displacing inhabitants of captured areas with predominantly Arab population such as Tell Abyad. These displacements were considered attempts at ethnic cleansing.[249] Contrasting with these reports, the head of the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights has rebutted reports of ethnic cleansing in Tel Abyad against the Turkmen and Arabic population[250] and the U.N. Independent International Commission of Inquiry also released a report that stated that the commission did not find evidence of YPG or SDF forces committing ethnic cleansing in order to change the demographic composition of territories under their control.[251]

Demographics

The demographics of the region have historically been highly diverse. One major shift in modern times was in the early part of the 20th century due to the Assyrian and Armenian Genocides, when many Assyrians and Armenians fled to Syria from Turkey. This was followed by many Kurds fleeing Turkey in the aftermath of Sheikh Said rebellion. Another major shift in modern times was the Baath policy of settling additional Arab population in Northern Syria. Most recently, during the Syrian Civil War, many refugees have fled to the north of the country. Some ethnic Arab citizens from Iraq have fled to Northern Syria as well.[242][252][253] However, as of January 2018, only two million people are estimated to remain in the area under the region's administration with estimates of around half a million people emigrating since the beginning of the civil war, to a large degree because of the economic hardships the region has faced during the war.[6]

Ethnic groups

Two ethnic groups have a significant presence throughout Northern Syria:

- Kurds are an ethnic group[254] living in northeastern and northwestern Syria, culturally and linguistically classified among the Iranian peoples.[255][256][257] Many Kurds consider themselves descended from the ancient Iranian people of the Medes,[258] using a calendar dating from 612 B.C., when the Assyrian capital of Nineveh was conquered by the Medes.[259] Kurds formed 55% of the 2010 population of what now is both Jazira Region and Euphrates Region.[191] During the Syrian civil war, many Kurds who had lived elsewhere in Syria fled back to their traditional lands in Northern Syria.

- Arabs are an ethnic group[260][261][262][263][264] or ethnolinguistic group[265][266][267] living throughout Northern Syria, mainly defined by Arabic as their first language. They encompass Bedouin tribes who trace their ancestry to the Arabian Peninsula as well as arabized indigenous peoples and preexisting Arab groups.[268][269] Arabs form the majority or plurality in some parts of Northern Syria, in particular in the southern parts of the Jazira Region, in Tell Abyad District and in Azaz District. While in Shahba region the term Arab is mainly used to denote arabized Kurds[191] and arabized Syrians,[268] in Euphrates Region and in Jazira Region it mainly denotes ethnic Arab Bedouin populations.[269]

Two ethnic groups have a significant presence in certain regions of Northern Syria:

- Assyrians are an ethnic group.[270][271] Their presence in Syria is in the Jazira Region of the autonomous region, particularly in the urban areas (Qamishli, al-Hasakah, Ras al-Ayn, Al-Malikiyah, Al-Qahtaniyah), in the northeastern corner and in villages along the Khabur River in the Tell Tamer area. They traditionally speak varieties of Syriac-Aramaic, a Semitic language.[272] There are many Assyrians among recent refugees to Northern Syria, fleeing Islamist violence elsewhere in Syria back to their traditional lands.[273] In the secular polyethnic political climate of the region, the Dawronoye modernization movement has a growing influence on Assyrian identity in the 21st century.[25]

- Turkmen are an ethnic group with a major presence in the area between Afrin Region and Euphrates Region, where they form regional majorities in the countryside from Azaz and Mare' to Jarabulus, and a minor presence in Afrin Region and Euphrates Region.

There are also smaller minorities of Armenians throughout Northern Syria as well as Chechens in Ras al-Ayn.

Languages

Regarding the status of different languages in the autonomous region, its "Social Contract" stipulates that "all languages in Northern Syria are equal in all areas of life, including social, educational, cultural, and administrative dealings. Every people shall organize its life and manage its affairs using its mother tongue."[274] In practice, Arabic and Kurmanji are predominantly used across all areas and for most official documents, with Syriac being mainly used in the Jazira Region with some usage across all areas while Turkish and Circassian are also used in the region of Manbij.

The four main languages spoken in Northern Syria are the following, and are from three different language families:

- Kurdish (in Northern Kurdish dialect), a Northwestern Iranian language[275][276] from the Indo-European language family.

- Arabic (in North Mesopotamian Arabic dialect, in writing Modern Standard Arabic), a Central Semitic language from the Semitic language family

- Syriac-Aramaic mainly in the Surayt/Turoyo and Assyrian Neo-Aramaic varieties (mainly Classical Syriac in writing), Northwest Semitic languages from the Semitic language family.

- Turkish (in Syrian Turkmen dialect), from the Turkic language family.

For these four languages, three different scripts are in use in Northern Syria:

- The Latin alphabet for Kurdish and Turkish

- The Arabic alphabet (abjad) for Arabic

- The Syriac alphabet for Syriac-Aramaic

Religion

Most ethnic Kurdish and Arab people in Northern Syria adhere to Sunni Islam, while ethnic Assyrian people generally are Syriac Orthodox, Chaldean Catholic, Syriac Catholic or adherents of the Assyrian Church of the East. There are also adherents to other religions, such as Yazidism.[277] The dominant PYD party and the political administration in the region are decidedly secular and laicist.[25]

Population centres

This list includes all cities and towns in the region with more than 10,000 inhabitants. The population figures are given according to the 2004 Syrian census.[278]

Cities highlighted in light grey are partially controlled by the Syrian government.[279][280][281][282]

| English Name | Kurdish Name | Arabic Name | Syriac Name | Turkish Name | Population | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raqqa | Reqa | الرقة | ܪܩܗ | Rakka | 220,488 | Raqqa |

| Al-Hasakah | Hesîçe | الحسكة | ܚܣܟܗ | Haseke | 188,160 | Jazira |

| Qamishli | Qamişlo | القامشلي | ܩܡܫܠܐ | Kamışlı | 184,231 | Jazira |

| Manbij | Menbîç | منبج | ܡܒܘܓ | Münbiç | 99,497 | Manbij |

| Tabqa | Tebqa | الطبقة | ܛܒܩܗ | Tabka | 69,425 | Tabqa |

| Kobani | Kobanî | عين العرب | ܟܘܒܐܢܝ | Arappınar | 44,821 | Euphrates |

| Hajin | هجين | ܗܓܝܢ | 37,935 | Deir Ez-Zor | ||

| Amuda | Amûdê | عامودا | ܥܐܡܘܕܐ | Amudiye | 26,821 | Jazira |

| Al-Malikiyah | Dêrika Hemko | المالكية | ܕܪܝܟ | Deyrik | 26,311 | Jazira |

| Gharanij | غرانيج | ܓܪܐܢܝܓ | 23,009 | Deir Ez-Zor | ||

| Abu Hamam | أبو حمام | ܐܒܘ ܚܡܐܡ | 21,947 | Deir Ez-Zor | ||

| Tell Rifaat | Arfêd | تل رفعت | ܬܠ ܪܦܥܬ | Tel Rıfat | 20,514 | Afrin |

| Al-Shaafah | الشعفة | ܫܥܦܗ | 18,956 | Deir Ez-Zor | ||

| Al-Qahtaniyah | Tirbespî | القحطانية | ܩܒܪ̈ܐ ܚܘܪ̈ܐ | Kubur el Bid | 16,946 | Jazira |

| Al-Mansurah | المنصورة | ܡܢܨܘܪܗ | 16,158 | Tabqa[283] | ||

| Al-Shaddadah | Şeddadê | الشدادي | ܫܕܐܕܝ | Şaddadi | 15,806 | Jazira |

| Al-Muabbada | Girkê Legê | المعبدة | ܡܥܒܕܗ | Muabbada | 15,759 | Jazira |

| Al-Kishkiyah | الكشكية | ܟܫܟܝܗ | 14,979 | Deir Ez-Zor | ||

| Al-Sabaa wa Arbain | Seba û Erbîyn | السبعة وأربعين | ܣܒܥܗ ܘܐܪܒܥܝܢ | El Seba ve Arbayn | 14,177 | Jazira |

| Rmelan | Rimêlan | رميلان | ܪܡܝܠܐܢ | Rimelan | 11,500 | Jazira |

| Al-Baghuz Fawqani | الباغوز فوقاني | ܒܐܓܘܙ ܦܘܩܐܢܝ | 10,649 | Deir Ez-Zor |

External relations

Relations with the Syrian government

Currently, the relations of the region to the Damascus government are determined by the context of the Syrian civil war. The Constitution of Syria and the Constitution of North and East Syria are legally incompatible with respect to legislative and executive authority. In the military realm, combat between the People's Protection Units (YPG) and Syrian government forces has been rare, in the most instances some of the territory still controlled by the Syrian government in Qamishli and al-Hasakah has been lost to the YPG. In some military campaigns, in particular in northern Aleppo governate and in al-Hasakah, YPG and Syrian government forces have tacitly cooperated against Islamist forces, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and others.[20]

The region does not state to pursue full independence but rather autonomy within a federal and democratic Syria.[32] In July 2016, Constituent Assembly co-chair Hediya Yousef formulated the region's approach towards Syria as follows:[284]

We believe that a federal system is ideal form of governance for Syria. We see that in many parts of the world, a federal framework enables people to live peacefully and freely within territorial borders. The people of Syria can also live freely in Syria. We will not allow for Syria to be divided; all we want is the democratization of Syria; its citizens must live in peace, and enjoy and cherish the ethnic diversity of the national groups inhabiting the country.

In March 2015, the Syrian Information Minister announced that his government considered recognizing the Kurdish autonomy "within the law and constitution".[285] While the region's administration is not invited to the Geneva III peace talks on Syria,[286] or any of the earlier talks, Russia in particular calls for the region's inclusion and does to some degree carry the region's positions into the talks, as documented in Russia's May 2016 draft for a new constitution for Syria.[287] In October 2016, there were reports of a Russian initiative for federalization with a focus on northern Syria, which at its core called to turn the existing institutions of the region into legitimate institutions of Syria; also reported was its rejection for the time being by the Syrian government.[244] The Damascus ruling elite is split over the question whether the new model in the region can work in parallel and converge with the Syrian government, for the benefit of both, or if the agenda should be to centralize again all power at the end of the civil war, necessitating preparation for ultimate confrontation with the region's institutions.[288]

An analysis released in June 2017 described the region's "relationship with the regime fraught but functional" and a "semi-cooperative dynamic".[289] In late September 2017, Syria's Foreign Minister said that Damascus would consider granting Kurds more autonomy in the region once ISIL is defeated.[290]

On 13 October 2019, the SDF announced that it had reached an agreement with the Syrian Army which allowed the latter to enter the SDF-held cities of Manbij and Kobani in order to dissuade a Turkish attack on those cities as part of the cross-border offensive by Turkish and Turkish-backed Syrian rebels.[291] The Syrian Army also deployed in the north of Syria together with the SDF along the Syrian-Turkish border and entered into several SDF-held cities such as Ayn Issa and Tell Tamer.[292][293] Following the creation of the Second Northern Syria Buffer Zone the SDF stated that it was ready to merge with the Syrian Army if when a political settlement between the Syrian government and the SDF is achieved.[294]

Kurdish question

The region's dominant political party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), is a member organisation of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) organization; however, the other KCK member organisations in the neighbouring states (Turkey, Iran and Iraq) with Kurdish minorities are either outlawed (Turkish Kurdistan, Iranian Kurdistan) or politically marginal with respect to other Kurdish parties (Iraq). Expressions of sympathy for Syrian Kurds have been numerous among Kurds in Turkey.[295] During the Siege of Kobanî, some ethnic Kurdish citizens of Turkey crossed the border and volunteered in the defense of the town.[296][297]

The region's relationship with the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq is complicated. One context is that the governing party there, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), views itself and its affiliated Kurdish parties in other countries as a more conservative and nationalist alternative and competitor to the KCK political agenda and blueprint in general.[32] The political system of Iraqi Kurdistan[298] stands in stark contrast to the region's system. Like the KCK umbrella organization, the PYD has some anti-nationalist ideological leanings while having Kurdish nationalist factions as well.[299] They have traditionally been opposed by the Iraqi-Kurdish KDP-sponsored Kurdish National Council in Syria with more clear Kurdish nationalist leanings.[300]

International relations

The region's role in the international arena is comprehensive military cooperation of its militias under the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) umbrella with the United States and the international (US-led) coalition against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.[301][302] In a public statement in March 2016, the day after the declaration of the regions autonomy, U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter praised the People's Protection Units (YPG) militia as having "proven to be excellent partners of ours on the ground in fighting ISIL. We are grateful for that, and we intend to continue to do that, recognizing the complexities of their regional role."[303] Late October 2016, U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Stephen Townsend, the commander of the international Anti-ISIL-coalition, said that the SDF would lead the impending assault on Raqqa, ISIL's stronghold and capital, and that SDF commanders would plan the operation with advice from American and coalition troops.[304] At various times, the U.S. deployed U.S. troops embedded with the SDF to the border between the region and Turkey, in order to deter Turkish aggressions against the SDF.[305][306][307][308][309] In February 2018, the United States Department of Defense released a budget blueprint for 2019 with respect to the region, which included $300 million for the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and $250 million for border security.[310] In April 2018, the President of France , Emmanuel Macron dispatched troops to Manbij and Rmelan in a bid to assist Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) militias and in order to defuse tensions with Turkey.[311]

In the diplomatic field, the de facto autonomous region lacks any formal recognition. While there is comprehensive activity of reception of the region's representatives[312][313][314][315] and appreciation[316] with a broad range of countries, only Russia has on occasion openly supported the region's political ambition of federalization of Syria in the international arena,[244][287] while the U.S. does not.[317][318] After peace talks between Syrian civil war parties in Astana in January 2017, Russia offered a draft for a future constitution of Syria, which would, among other things, change the "Syrian Arab Republic" into the "Republic of Syria", introduce decentralized authorities as well as elements of federalism like "association areas", strengthen the parliament at the cost of the presidency, and realize secularism by abolishing Islamic jurisprudence as a source of legislation.[319][320][321][322] The region opened official representation offices in Moscow during 2016,[323] Stockholm,[324] Berlin,[325] Paris,[326] and The Hague.[327] A broad range of public voices in the U.S. and Europe have called for more formal recognition of the region.[241][242][328][329] International cooperation has been in the field of educational and cultural institutions, like the cooperation agreement of Paris 8 University with the newly founded University of Rojava in Qamishli,[330] or planning for a France cultural centre in Amuda.[331][332][333]

Neighbouring Turkey is consistently hostile, which has been attributed to a perceived threat from the region's emergence, in that it would encourage activism for autonomy among Kurds in Turkey in the Kurdish–Turkish conflict. In this context, in particular the region's leading Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the YPG militia being members of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) network of organisations, which also includes both political and military Kurdish organizations in Turkey itself, including the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). Turkey's policy towards the region is based on an economic blockade,[241] persistent attempts of international isolation,[334] opposition to the cooperation between the American-led anti-ISIL coalition and the Syrian Democratic Forces,[335] and support of Islamist opposition fighters hostile to the autonomous region,[336][337][338] with some reports even including ISIL among these.[339][340][341] Turkey has on several occasions militarily attacked the region's territory and defence forces.[342][343][344] This has resulted in some expressions of international solidarity with the region.[lower-alpha 2]

On 9 October 2019, Turkey launched an attack on northern Syria "to destroy the terror corridor" on the Turkish southern border, as president Erdogan put it, after US President Donald Trump abandoned his support. Subsequent media reports have speculated that the offensive would lead to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people.[349]

Syrian Constitutional Committee

On November 20, 2019, a new Syrian Constitutional Committee began operating in order to discuss a new settlement and to draft a new constitution for Syria.[350] This committee comprises about 150 members. It includes representatives of the Syrian regime, opposition groups, and countries serving as guarantors of the process such as e.g. Russia. However, this committee has faced strong opposition from the Assad regime. 50 of the committee members represent the regime, and 50 members represent the opposition. The committee began its work in November 2019 in Geneva, under UN auspices. However, the Assad regime delegation left on the second day of the process.[350]

At a summit in October 2018, envoys from Russia, Turkey, France and Germany issued a joint statement affirming the need to respect territorial integrity of Syria as a whole. This forms one basis for their role as "guarantor nations." [350]

The second round of talks occurred around November 25, but was not successful due to opposition from the Assad regime.[350] At the Astana Process meeting in December 2019, a UN official stated that in order for the third round of talks to proceed, co-chairs from the Assad regime and the opposition need to agree on an agenda.[350]

The committee has two co-chairs, Ahmad Kuzbari representing the Assad regime, and Hadi Albahra from the opposition. It is unclear if the third round of talks will proceed on a firm schedule, until the Assad regime provides its assent to participate.[350]

EU conference

In December 2019, the EU held an international conference which condemned any suppression of the Kurds, and called for the self-declared Automnomous Administration in Rojava to be preserved and to be reflected in any new Syrian Constitution. The Kurds are concerned that the independence of their declared Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES) in Rojava might be severely curtailed.[351]

See also

- Iraqi Kurdistan

- Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities

Notes

- ↑ The name "Rojava" ("The West") was initially used by the region's PYD-led government, before its usage was dropped in 2016.[7][8][9] Since then, the name is still used by some locals and international observers.[10][11]

- ↑ Concerns over Turkish actions were expressed by US, Russian and Germany officials.[345][346][347][348][309]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "New administration formed for northeastern Syria" (in en). http://www.kurdistan24.net/en/news/c9e03dab-6265-4a9a-91ee-ea8d2a93c657. "By Wladimir van Wilgenburg"

- ↑ Fetah, Vîviyan (17 July 2018). "Îlham Ehmed: Dê rêxistinên me li Şamê jî ava bibin" (in ku). www.rudaw.net. Rudaw Media Network. https://www.rudaw.net/kurmanci/middleeast/syria/170720181. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Syrian Kurds declare new federation in bid for recognition". Middle East Eye. 17 March 2016. http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/kurdish-pyd-declares-federalism-northern-syria-1311505605.

- ↑ "Amina Omar ,Ryad Derrar elected as co-chairs of MSD" (in en). http://www.hawarnews.com/en/haber/amina-omar-ryad-derrar-elected-as-co-chairs-of-msd-h2572.html.

- ↑ "War Statistics / Syrian War Statistics - Syrian Civil War Map". https://syriancivilwarmap.com/war-statistics/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Sectarianism in Syria's Civil War". p. 24. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/SyriaAtlasCOMPLETE-3.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Lister (2015), p. 154.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), p. 89.

- ↑ "'Rojava' no longer exists, 'Northern Syria' adopted instead". https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/news/51940fb9-3aff-4e51-bcf8-b1629af00299/-Rojava--no-longer-exists---Northern-Syria--adopted-instead-.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Turkey's military operation in Syria: All the latest updates". al Jazeera. 14 October 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/turkey-military-operation-syria-latest-updates-191013083950643.html. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The Communist volunteers fighting the Turkish invasion of Syria". Morning Star. 31 October 2019. https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/f/communist-volunteers-fighting-turkish-invasion-syria.

- ↑ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 11, 95.

- ↑ Zabad (2017), pp. 219, 228.

- ↑ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 97–98.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Electoral Commission publish video of elections 2nd stage | ANHA". 1 December 2017. https://en.hawarnews.com/electoral-commission-publish-video-of-elections-2nd-stage/.

- ↑ "Delegation from the Democratic administration of Self-participate of self-participate in the first and second conference of the Shaba region". 4 February 2016. http://cantonafrin.com/en/news/view/1658.a-delegation-from-the-democratic-administration-of-self-participate-in-the-second-conference-of-the-el--shahba-region.html. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ "Turkey's Syria offensive explained in four maps". BBC. 14 October 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-49973218. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ↑ "Syria Kurds adopt constitution for autonomous federal region". TheNewArab. 31 December 2016. https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2016/12/30/syria-kurds-adopt-constitution-for-autonomous-federal-region. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ "Fight For Kobane May Have Created A New Alliance In Syria: Kurds And The Assad Regime". International Business Times. 8 October 2014. http://www.ibtimes.com/fight-kobane-may-have-created-new-alliance-syria-kurds-assad-regime-1701363. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Syria’s war: Assad on the offensive". The Economist. 2016-02-13. https://www.economist.com/news/21690203-city-was-once-syrias-largest-faces-siege-assadu2019s-grip-tightens. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ↑ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. xviii, 112.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Zabad (2017), pp. 219, 228–229.

- ↑ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. xviii, 66, 200.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Syria Kurds challenging traditions, promote civil marriage". ARA News. 2016-02-20. http://aranews.net/2016/02/syria-kurds-challenging-traditions-promote-civil-marriage/. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Carl Drott (25 May 2015). "The Revolutionaries of Bethnahrin". Warscapes. http://www.warscapes.com/reportage/revolutionaries-bethnahrin. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Zabad (2017), p. 219.

- ↑ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 156–163.

- ↑ "PYD leader: SDF operation for Raqqa countryside in progress, Syria can only be secular". ARA News. 28 May 2016. http://aranews.net/2016/05/poyd-leader-current-sdf-operation-recapture-northern-countryside-raqqa-not-city/. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 Ross, Carne (2015-09-30). "The Kurds' Democratic Experiment". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/30/opinion/the-kurds-democratic-experiment.html. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ↑ In der Maur, Renée; Staal, Jonas (2015). "Introduction". Stateless Democracy. Utrecht: BAK. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-77288-22-1. http://newworldsummit.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/NWA5-Stateless-Democracy1.pdf.

- ↑ Jongerden, Joost (5–6 December 2012). "Rethinking Politics and Democracy in the Middle East" (PDF). http://www.ekurd.net/mismas/articles/misc2012/12/turkey4358b.pdf. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "ANALYSIS: 'This is a new Syria, not a new Kurdistan'". MiddleEastEye. 2016-03-21. http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/analysis-kurds-syria-rojava-1925945786. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), p. 94.

- ↑ "Kurds accused of "ethnic cleansing" by Syria rebels". http://www.cbsnews.com/news/kurds-accused-ethnic-cleansing-syria-rebels-isis/. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Syrian rebels accuse Kurdish forces of 'ethnic cleansing' of Sunni Arabs". https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/11676808/Syrian-rebels-accuse-Kurdish-forces-of-ethnic-cleansing-of-Sunni-Arabs.html/. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Khalaf, Rana. "Governing Rojava Layers of Legitimacy in Syria". The Royal Institute of International Affairs. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/publications/research/2016-12-08-governing-rojava-khalaf.pdf.

- ↑ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 99, 114.

- ↑ Lister 2015, p. 154: "On 19 July the PYD formally announced that it had written a constitution for an autonomous Syrian Kurdish region to be known as West Kurdistan."

- ↑ "Yekîneya Antî Teror a Rojavayê Kurdistanê hate avakirin" (in Kurdish). 7 April 2015. http://ku.hawarnews.com/yekineya-anti-teror-a-rojavaye-kurdistane-hate-avakirin/. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, (2014), by Ofra Bengio, University of Texas Press

- ↑ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg (2019), pp. 89, 151–152.