Plane (geometry)

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

In mathematics, a plane is a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends indefinitely.[1] A plane is the two-dimensional analogue of a point (zero dimensions), a line (one dimension) and three-dimensional space. Planes can arise as subspaces of some higher-dimensional space, as with one of a room's walls, infinitely extended, or they may enjoy an independent existence in their own right, as in the setting of two-dimensional[2] Euclidean geometry.

When working exclusively in two-dimensional Euclidean space, the definite article is used, so the plane refers to the whole space. Many fundamental tasks in mathematics, geometry, trigonometry, graph theory, and graphing are performed in a two-dimensional space, often in the plane.

Euclidean geometry

Euclid set forth the first great landmark of mathematical thought, an axiomatic treatment of geometry.[3] He selected a small core of undefined terms (called common notions) and postulates (or axioms) which he then used to prove various geometrical statements. Although the plane in its modern sense is not directly given a definition anywhere in the Elements, it may be thought of as part of the common notions.[4] Euclid never used numbers to measure length, angle, or area. The Euclidean plane equipped with a chosen Cartesian coordinate system is called a Cartesian plane; a non-Cartesian Euclidean plane equipped with a polar coordinate system would be called a polar plane.

A plane is a ruled surface.

Representation

This section is solely concerned with planes embedded in three dimensions: specifically, in R3.

Determination by contained points and lines

In a Euclidean space of any number of dimensions, a plane is uniquely determined by any of the following:

- Three non-collinear points (points not on a single line).

- A line and a point not on that line.

- Two distinct but intersecting lines.

- Two distinct but parallel lines.

Properties

The following statements hold in three-dimensional Euclidean space but not in higher dimensions, though they have higher-dimensional analogues:

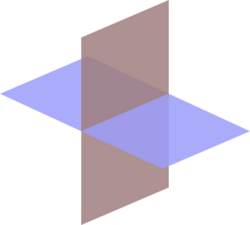

- Two distinct planes are either parallel or they intersect in a line.

- A line is either parallel to a plane, intersects it at a single point, or is contained in the plane.

- Two distinct lines perpendicular to the same plane must be parallel to each other.

- Two distinct planes perpendicular to the same line must be parallel to each other.

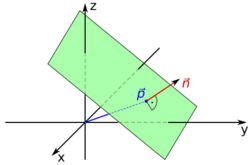

Point–normal form and general form of the equation of a plane

In a manner analogous to the way lines in a two-dimensional space are described using a point-slope form for their equations, planes in a three dimensional space have a natural description using a point in the plane and a vector orthogonal to it (the normal vector) to indicate its "inclination".

Specifically, let r0 be the position vector of some point P0 = (x0, y0, z0), and let n = (a, b, c) be a nonzero vector. The plane determined by the point P0 and the vector n consists of those points P, with position vector r, such that the vector drawn from P0 to P is perpendicular to n. Recalling that two vectors are perpendicular if and only if their dot product is zero, it follows that the desired plane can be described as the set of all points r such that

The dot here means a dot (scalar) product.

Expanded this becomes

which is the point–normal form of the equation of a plane.[5] This is just a linear equation

where

which is the expanded form of

In mathematics it is a common convention to express the normal as a unit vector, but the above argument holds for a normal vector of any non-zero length.

Conversely, it is easily shown that if a, b, c, and d are constants and a, b, and c are not all zero, then the graph of the equation is a plane having the vector n = (a, b, c) as a normal.[6] This familiar equation for a plane is called the general form of the equation of the plane.[7]

Thus for example a regression equation of the form y = d + ax + cz (with b = −1) establishes a best-fit plane in three-dimensional space when there are two explanatory variables.

Describing a plane with a point and two vectors lying on it

Alternatively, a plane may be described parametrically as the set of all points of the form

where s and t range over all real numbers, v and w are given linearly independent vectors defining the plane, and r0 is the vector representing the position of an arbitrary (but fixed) point on the plane. The vectors v and w can be visualized as vectors starting at r0 and pointing in different directions along the plane. The vectors v and w can be perpendicular, but cannot be parallel.

Describing a plane through three points

Let p1 = (x1, y1, z1), p2 = (x2, y2, z2), and p3 = (x3, y3, z3) be non-collinear points.

Method 1

The plane passing through p1, p2, and p3 can be described as the set of all points (x,y,z) that satisfy the following determinant equations:

Method 2

To describe the plane by an equation of the form , solve the following system of equations:

This system can be solved using Cramer's rule and basic matrix manipulations. Let

If D is non-zero (so for planes not through the origin) the values for a, b and c can be calculated as follows:

These equations are parametric in d. Setting d equal to any non-zero number and substituting it into these equations will yield one solution set.

Method 3

This plane can also be described by the "point and a normal vector" prescription above. A suitable normal vector is given by the cross product and the point r0 can be taken to be any of the given points p1, p2 or p3[8] (or any other point in the plane).

Operations

Distance from a point to a plane

For a plane and a point not necessarily lying on the plane, the shortest distance from to the plane is

It follows that lies in the plane if and only if D = 0.

If , meaning that a, b, and c are normalized,[9] then the equation becomes

Another vector form for the equation of a plane, known as the Hesse normal form relies on the parameter D. This form is:[7]

where is a unit normal vector to the plane, a position vector of a point of the plane and D0 the distance of the plane from the origin.

The general formula for higher dimensions can be quickly arrived at using vector notation. Let the hyperplane have equation , where the is a normal vector and is a position vector to a point in the hyperplane. We desire the perpendicular distance to the point . The hyperplane may also be represented by the scalar equation , for constants . Likewise, a corresponding may be represented as . We desire the scalar projection of the vector in the direction of . Noting that (as satisfies the equation of the hyperplane) we have

Line–plane intersection

In analytic geometry, the intersection of a line and a plane in three-dimensional space can be the empty set, a point, or a line.

Line of intersection between two planes

The line of intersection between two planes and where are normalized is given by

where

This is found by noticing that the line must be perpendicular to both plane normals, and so parallel to their cross product (this cross product is zero if and only if the planes are parallel, and are therefore non-intersecting or entirely coincident).

The remainder of the expression is arrived at by finding an arbitrary point on the line. To do so, consider that any point in space may be written as , since is a basis. We wish to find a point which is on both planes (i.e. on their intersection), so insert this equation into each of the equations of the planes to get two simultaneous equations which can be solved for and .

If we further assume that and are orthonormal then the closest point on the line of intersection to the origin is . If that is not the case, then a more complex procedure must be used.[10]

Dihedral angle

Given two intersecting planes described by and , the dihedral angle between them is defined to be the angle between their normal directions:

Planes in various areas of mathematics

In addition to its familiar geometric structure, with isomorphisms that are isometries with respect to the usual inner product, the plane may be viewed at various other levels of abstraction. Each level of abstraction corresponds to a specific category.

At one extreme, all geometrical and metric concepts may be dropped to leave the topological plane, which may be thought of as an idealized homotopically trivial infinite rubber sheet, which retains a notion of proximity, but has no distances. The topological plane has a concept of a linear path, but no concept of a straight line. The topological plane, or its equivalent the open disc, is the basic topological neighborhood used to construct surfaces (or 2-manifolds) classified in low-dimensional topology. Isomorphisms of the topological plane are all continuous bijections. The topological plane is the natural context for the branch of graph theory that deals with planar graphs, and results such as the four color theorem.

The plane may also be viewed as an affine space, whose isomorphisms are combinations of translations and non-singular linear maps. From this viewpoint there are no distances, but collinearity and ratios of distances on any line are preserved.

Differential geometry views a plane as a 2-dimensional real manifold, a topological plane which is provided with a differential structure. Again in this case, there is no notion of distance, but there is now a concept of smoothness of maps, for example a differentiable or smooth path (depending on the type of differential structure applied). The isomorphisms in this case are bijections with the chosen degree of differentiability.

In the opposite direction of abstraction, we may apply a compatible field structure to the geometric plane, giving rise to the complex plane and the major area of complex analysis. The complex field has only two isomorphisms that leave the real line fixed, the identity and conjugation.

In the same way as in the real case, the plane may also be viewed as the simplest, one-dimensional (over the complex numbers) complex manifold, sometimes called the complex line. However, this viewpoint contrasts sharply with the case of the plane as a 2-dimensional real manifold. The isomorphisms are all conformal bijections of the complex plane, but the only possibilities are maps that correspond to the composition of a multiplication by a complex number and a translation.

In addition, the Euclidean geometry (which has zero curvature everywhere) is not the only geometry that the plane may have. The plane may be given a spherical geometry by using the stereographic projection. This can be thought of as placing a sphere on the plane (just like a ball on the floor), removing the top point, and projecting the sphere onto the plane from this point). This is one of the projections that may be used in making a flat map of part of the Earth's surface. The resulting geometry has constant positive curvature.

Alternatively, the plane can also be given a metric which gives it constant negative curvature giving the hyperbolic plane. The latter possibility finds an application in the theory of special relativity in the simplified case where there are two spatial dimensions and one time dimension. (The hyperbolic plane is a timelike hypersurface in three-dimensional Minkowski space.)

Topological and differential geometric notions

The one-point compactification of the plane is homeomorphic to a sphere (see stereographic projection); the open disk is homeomorphic to a sphere with the "north pole" missing; adding that point completes the (compact) sphere. The result of this compactification is a manifold referred to as the Riemann sphere or the complex projective line. The projection from the Euclidean plane to a sphere without a point is a diffeomorphism and even a conformal map.

The plane itself is homeomorphic (and diffeomorphic) to an open disk. For the hyperbolic plane such diffeomorphism is conformal, but for the Euclidean plane it is not.

See also

- Face (geometry)

- Flat (geometry)

- Half-plane

- Hyperplane

- Line–plane intersection

- Plane coordinates

- Plane of incidence

- Plane of rotation

- Point on plane closest to origin

- Polygon

- Projective plane

Notes

- ↑ In Euclidean geometry it extends infinitely, but in, e.g., Elliptic geometry, it wraps around.

- ↑ Euclid's Elements also covered solid geometry.

- ↑ Eves 1963, p. 19

- ↑ Joyce, D.E. (1996), Euclid's Elements, Book I, Definition 7, Clark University, http://aleph0.clarku.edu/~djoyce/java/elements/bookI/defI7.html, retrieved 8 August 2009

- ↑ Anton 1994, p. 155

- ↑ Anton 1994, p. 156

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Weisstein, Eric W. (2009), "Plane", MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource, http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Plane.html, retrieved 2009-08-08

- ↑ Dawkins, Paul, "Equations of Planes", Calculus III, http://tutorial.math.lamar.edu/Classes/CalcIII/EqnsOfPlanes.aspx

- ↑ To normalize arbitrary coefficients, divide each of a, b, c and d by (which can not be 0). The "new" coefficients are now normalized and the following formula is valid for the "new" coefficients.

- ↑ Plane-Plane Intersection - from Wolfram MathWorld. Mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

References

- Anton, Howard (1994), Elementary Linear Algebra (7th ed.), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-58742-7

- Eves, Howard (1963), A Survey of Geometry, I, Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Plane", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/p072790

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Plane". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Plane.html.

- "Easing the Difficulty of Arithmetic and Planar Geometry" is an Arabic manuscript, from the 15th century, that serves as a tutorial about plane geometry and arithmetic.

KSF

KSF