Quantum computing

From HandWiki - Reading time: 43 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 43 min

A quantum computer is a computer that exploits quantum mechanical phenomena. At small scales, physical matter exhibits properties of both particles and waves, and quantum computing leverages this behavior using specialized hardware. Classical physics cannot explain the operation of these quantum devices, and a scalable quantum computer could perform some calculations exponentially faster than any modern "classical" computer.

In particular, a large-scale quantum computer could break widely used encryption schemes and aid physicists in performing physical simulations; however, the current state of the art is largely experimental and impractical.

The basic unit of information in quantum computing is the qubit, similar to the bit in traditional digital electronics. Unlike a classical bit, a qubit can exist in a superposition of its two "basis" states, which loosely means that it is in both states simultaneously. When measuring a qubit, the result is a probabilistic output of a classical bit. If a quantum computer manipulates the qubit in a particular way, wave interference effects can amplify the desired measurement results. The design of quantum algorithms involves creating procedures that allow a quantum computer to perform calculations efficiently and quickly.

Physically engineering high-quality qubits has proven challenging. If a physical qubit is not sufficiently isolated from its environment, it suffers from quantum decoherence, introducing noise into calculations. National governments have invested heavily in experimental research that aims to develop scalable qubits with longer coherence times and lower error rates. Two of the most promising technologies are superconductors (which isolate an electrical current by eliminating electrical resistance) and ion traps (which confine a single atomic particle using electromagnetic fields).

Any computational problem that can be solved by a classical computer can also be solved by a quantum computer.[2] Conversely, any problem that can be solved by a quantum computer can also be solved by a classical computer, at least in principle given enough time. In other words, quantum computers obey the Church–Turing thesis. This means that while quantum computers provide no additional advantages over classical computers in terms of computability, quantum algorithms for certain problems have significantly lower time complexities than corresponding known classical algorithms. Notably, quantum computers are believed to be able to solve many problems quickly that no classical computer could solve in any feasible amount of time—a feat known as "quantum supremacy." The study of the computational complexity of problems with respect to quantum computers is known as quantum complexity theory.

History

For many years, the fields of quantum mechanics and computer science formed distinct academic communities.[3] Modern quantum theory developed in the 1920s to explain the wave–particle duality observed at atomic scales,[4] and digital computers emerged in the following decades to replace human computers for tedious calculations.[5] Both disciplines had practical applications during World War II; computers played a major role in wartime cryptography,[6] and quantum physics was essential for the nuclear physics used in the Manhattan Project.[7]

As physicists applied quantum mechanical models to computational problems and swapped digital bits for qubits, the fields of quantum mechanics and computer science began to converge. In 1980, Paul Benioff introduced the quantum Turing machine, which uses quantum theory to describe a simplified computer.[8] When digital computers became faster, physicists faced an exponential increase in overhead when simulating quantum dynamics,[9] prompting Yuri Manin and Richard Feynman to independently suggest that hardware based on quantum phenomena might be more efficient for computer simulation.[10][11][12] In a 1984 paper, Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard applied quantum theory to cryptography protocols and demonstrated that quantum key distribution could enhance information security.[13][14]

Quantum algorithms then emerged for solving oracle problems, such as Deutsch's algorithm in 1985,[15] the Bernstein–Vazirani algorithm in 1993,[16] and Simon's algorithm in 1994.[17] These algorithms did not solve practical problems, but demonstrated mathematically that one could gain more information by querying a black box with a quantum state in superposition, sometimes referred to as quantum parallelism.[18] Peter Shor built on these results with his 1994 algorithms for breaking the widely used RSA and Diffie–Hellman encryption protocols,[19] which drew significant attention to the field of quantum computing.[20] In 1996, Grover's algorithm established a quantum speedup for the widely applicable unstructured search problem.[21][22] The same year, Seth Lloyd proved that quantum computers could simulate quantum systems without the exponential overhead present in classical simulations,[23] validating Feynman's 1982 conjecture.[24]

Over the years, experimentalists have constructed small-scale quantum computers using trapped ions and superconductors.[25] In 1998, a two-qubit quantum computer demonstrated the feasibility of the technology,[26][27] and subsequent experiments have increased the number of qubits and reduced error rates.[25] In 2019, Google AI and NASA announced that they had achieved quantum supremacy with a 54-qubit machine, performing a computation that is impossible for any classical computer.[28][29][30] However, the validity of this claim is still being actively researched.[31][32]

The threshold theorem shows how increasing the number of qubits can mitigate errors,[33] yet fully fault-tolerant quantum computing remains "a rather distant dream".[34] According to some researchers, noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) machines may have specialized uses in the near future, but noise in quantum gates limits their reliability.[34]

Investment in quantum computing research has increased in the public and private sectors.[35][36] As one consulting firm summarized,[37]

... investment dollars are pouring in, and quantum-computing start-ups are proliferating. ... While quantum computing promises to help businesses solve problems that are beyond the reach and speed of conventional high-performance computers, use cases are largely experimental and hypothetical at this early stage.

Quantum information processing

Computer engineers typically describe a modern computer's operation in terms of classical electrodynamics. Within these "classical" computers, some components (such as semiconductors and random number generators) may rely on quantum behavior, but these components are not isolated from their environment, so any quantum information quickly decoheres. While programmers may depend on probability theory when designing a randomized algorithm, quantum mechanical notions like superposition and interference are largely irrelevant for program analysis.

Quantum programs, in contrast, rely on precise control of coherent quantum systems. Physicists describe these systems mathematically using linear algebra. Complex numbers model probability amplitudes, vectors model quantum states, and matrices model the operations that can be performed on these states. Programming a quantum computer is then a matter of composing operations in such a way that the resulting program computes a useful result in theory and is implementable in practice.

The prevailing model of quantum computation describes the computation in terms of a network of quantum logic gates.[38] This model is a complex linear-algebraic generalization of boolean circuits.[lower-alpha 1]

Quantum information

The qubit serves as the basic unit of quantum information. It represents a two-state system, just like a classical bit, except that it can exist in a superposition of its two states. In one sense, a superposition is like a probability distribution over the two values. However, a quantum computation can be influenced by both values at once, inexplicable by either state individually. In this sense, a "superposed" qubit stores both values simultaneously.

A two-dimensional vector mathematically represents a qubit state. Physicists typically use Dirac notation for quantum mechanical linear algebra, writing |ψ⟩ 'ket psi' for a vector labeled ψ. Because a qubit is a two-state system, any qubit state takes the form α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, where |0⟩ and |1⟩ are the standard basis states,[lower-alpha 2] and α and β are the probability amplitudes. If either α or β is zero, the qubit is effectively a classical bit; when both are nonzero, the qubit is in superposition. Such a quantum state vector acts similarly to a (classical) probability vector, with one key difference: unlike probabilities, probability amplitudes are not necessarily positive numbers. Negative amplitudes allow for destructive wave interference.[lower-alpha 3]

When a qubit is measured in the standard basis, the result is a classical bit. The Born rule describes the norm-squared correspondence between amplitudes and probabilities—when measuring a qubit α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, the state collapses to |0⟩ with probability |α|2, or to |1⟩ with probability |β|2. Any valid qubit state has coefficients α and β such that |α|2 + |β|2 = 1. As an example, measuring the qubit 1/√2|0⟩ + 1/√2|1⟩ would produce either |0⟩ or |1⟩ with equal probability.

Each additional qubit doubles the dimension of the state space. As an example, the vector 1/√2|00⟩ + 1/√2|01⟩ represents a two-qubit state, a tensor product of the qubit |0⟩ with the qubit 1/√2|0⟩ + 1/√2|1⟩. This vector inhabits a four-dimensional vector space spanned by the basis vectors |00⟩, |01⟩, |10⟩, and |11⟩. The Bell state 1/√2|00⟩ + 1/√2|11⟩ is impossible to decompose into the tensor product of two individual qubits—the two qubits are entangled because their probability amplitudes are correlated. In general, the vector space for an n-qubit system is 2n-dimensional, and this makes it challenging for a classical computer to simulate a quantum one: representing a 100-qubit system requires storing 2100 classical values.

Unitary operators

The state of this one-qubit quantum memory can be manipulated by applying quantum logic gates, analogous to how classical memory can be manipulated with classical logic gates. One important gate for both classical and quantum computation is the NOT gate, which can be represented by a matrix [math]\displaystyle{ X := \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math] Mathematically, the application of such a logic gate to a quantum state vector is modelled with matrix multiplication. Thus

- [math]\displaystyle{ X|0\rangle = |1\rangle }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X|1\rangle = |0\rangle }[/math].

The mathematics of single qubit gates can be extended to operate on multi-qubit quantum memories in two important ways. One way is simply to select a qubit and apply that gate to the target qubit while leaving the remainder of the memory unaffected. Another way is to apply the gate to its target only if another part of the memory is in a desired state. These two choices can be illustrated using another example. The possible states of a two-qubit quantum memory are [math]\displaystyle{ |00\rangle := \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix};\quad |01\rangle := \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix};\quad |10\rangle := \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix};\quad |11\rangle := \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math] The CNOT gate can then be represented using the following matrix: [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CNOT} := \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math] As a mathematical consequence of this definition, [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CNOT}|00\rangle = |00\rangle }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CNOT}|01\rangle = |01\rangle }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CNOT}|10\rangle = |11\rangle }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{CNOT}|11\rangle = |10\rangle }[/math]. In other words, the CNOT applies a NOT gate ([math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] from before) to the second qubit if and only if the first qubit is in the state [math]\displaystyle{ |1\rangle }[/math]. If the first qubit is [math]\displaystyle{ |0\rangle }[/math], nothing is done to either qubit.

In summary, a quantum computation can be described as a network of quantum logic gates and measurements. However, any measurement can be deferred to the end of quantum computation, though this deferment may come at a computational cost, so most quantum circuits depict a network consisting only of quantum logic gates and no measurements.

Quantum parallelism

Quantum parallelism refers to the ability of quantum computers to evaluate a function for multiple input values simultaneously. This can be achieved by preparing a quantum system in a superposition of input states, and applying a unitary transformation that encodes the function to be evaluated. The resulting state encodes the function's output values for all input values in the superposition, allowing for the computation of multiple outputs simultaneously. This property is key to the speedup of many quantum algorithms.[18]

Quantum programming

There are a number of models of computation for quantum computing, distinguished by the basic elements in which the computation is decomposed.

Gate array

A quantum gate array decomposes computation into a sequence of few-qubit quantum gates. A quantum computation can be described as a network of quantum logic gates and measurements. However, any measurement can be deferred to the end of quantum computation, though this deferment may come at a computational cost, so most quantum circuits depict a network consisting only of quantum logic gates and no measurements.

Any quantum computation (which is, in the above formalism, any unitary matrix of size [math]\displaystyle{ 2^n \times 2^n }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] qubits) can be represented as a network of quantum logic gates from a fairly small family of gates. A choice of gate family that enables this construction is known as a universal gate set, since a computer that can run such circuits is a universal quantum computer. One common such set includes all single-qubit gates as well as the CNOT gate from above. This means any quantum computation can be performed by executing a sequence of single-qubit gates together with CNOT gates. Though this gate set is infinite, it can be replaced with a finite gate set by appealing to the Solovay-Kitaev theorem.

Measurement-based quantum computing

A measurement-based quantum computer decomposes computation into a sequence of Bell state measurements and single-qubit quantum gates applied to a highly entangled initial state (a cluster state), using a technique called quantum gate teleportation.

Adiabatic quantum computing

An adiabatic quantum computer, based on quantum annealing, decomposes computation into a slow continuous transformation of an initial Hamiltonian into a final Hamiltonian, whose ground states contain the solution.[41]

Topological quantum computing

A topological quantum computer decomposes computation into the braiding of anyons in a 2D lattice.[42]

Quantum Turing machine

A quantum Turing machine is the quantum analog of a Turing machine.[8] All of these models of computation—quantum circuits,[43] one-way quantum computation,[44] adiabatic quantum computation,[45] and topological quantum computation[46]—have been shown to be equivalent to the quantum Turing machine; given a perfect implementation of one such quantum computer, it can simulate all the others with no more than polynomial overhead. This equivalence need not hold for practical quantum computers, since the overhead of simulation may be too large to be practical.

Communication

Quantum cryptography enables new ways to transmit data securely; for example, quantum key distribution uses entangled quantum states to establish secure cryptographic keys.[47] When a sender and receiver exchange quantum states, they can guarantee that the message is not intercepted, as any unauthorized eavesdropper would disturb the delicate quantum system and introduce a detectable change.[48] With the right cryptographic protocols, the sender and receiver can thus establish shared private information resistant to eavesdropping.[13][49]

Algorithms

Progress in finding quantum algorithms typically focuses on this quantum circuit model, though exceptions like the quantum adiabatic algorithm exist. Quantum algorithms can be roughly categorized by the type of speedup achieved over corresponding classical algorithms.[50]

Quantum algorithms that offer more than a polynomial speedup over the best-known classical algorithm include Shor's algorithm for factoring and the related quantum algorithms for computing discrete logarithms, solving Pell's equation, and more generally solving the hidden subgroup problem for abelian finite groups.[50] These algorithms depend on the primitive of the quantum Fourier transform. No mathematical proof has been found that shows that an equally fast classical algorithm cannot be discovered, but evidence suggests that this is unlikely.[51] Certain oracle problems like Simon's problem and the Bernstein–Vazirani problem do give provable speedups, though this is in the quantum query model, which is a restricted model where lower bounds are much easier to prove and doesn't necessarily translate to speedups for practical problems.

Other problems, including the simulation of quantum physical processes from chemistry and solid-state physics, the approximation of certain Jones polynomials, and the quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations have quantum algorithms appearing to give super-polynomial speedups and are BQP-complete. Because these problems are BQP-complete, an equally fast classical algorithm for them would imply that no quantum algorithm gives a super-polynomial speedup, which is believed to be unlikely.[52]

Some quantum algorithms, like Grover's algorithm and amplitude amplification, give polynomial speedups over corresponding classical algorithms.[50] Though these algorithms give comparably modest quadratic speedup, they are widely applicable and thus give speedups for a wide range of problems.[22]

Post-quantum cryptography

A notable application of quantum computation is for attacks on cryptographic systems that are currently in use. Integer factorization, which underpins the security of public key cryptographic systems, is believed to be computationally infeasible with an ordinary computer for large integers if they are the product of few prime numbers (e.g., products of two 300-digit primes).[53] By comparison, a quantum computer could solve this problem exponentially faster using Shor's algorithm to find its factors.[54] This ability would allow a quantum computer to break many of the cryptographic systems in use today, in the sense that there would be a polynomial time (in the number of digits of the integer) algorithm for solving the problem. In particular, most of the popular public key ciphers are based on the difficulty of factoring integers or the discrete logarithm problem, both of which can be solved by Shor's algorithm. In particular, the RSA, Diffie–Hellman, and elliptic curve Diffie–Hellman algorithms could be broken. These are used to protect secure Web pages, encrypted email, and many other types of data. Breaking these would have significant ramifications for electronic privacy and security.

Identifying cryptographic systems that may be secure against quantum algorithms is an actively researched topic under the field of post-quantum cryptography.[55][56] Some public-key algorithms are based on problems other than the integer factorization and discrete logarithm problems to which Shor's algorithm applies, like the McEliece cryptosystem based on a problem in coding theory.[55][57] Lattice-based cryptosystems are also not known to be broken by quantum computers, and finding a polynomial time algorithm for solving the dihedral hidden subgroup problem, which would break many lattice based cryptosystems, is a well-studied open problem.[58] It has been proven that applying Grover's algorithm to break a symmetric (secret key) algorithm by brute force requires time equal to roughly 2n/2 invocations of the underlying cryptographic algorithm, compared with roughly 2n in the classical case,[59] meaning that symmetric key lengths are effectively halved: AES-256 would have the same security against an attack using Grover's algorithm that AES-128 has against classical brute-force search (see Key size).

Search problems

The most well-known example of a problem that allows for a polynomial quantum speedup is unstructured search, which involves finding a marked item out of a list of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] items in a database. This can be solved by Grover's algorithm using [math]\displaystyle{ O(\sqrt{n}) }[/math] queries to the database, quadratically fewer than the [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega(n) }[/math] queries required for classical algorithms. In this case, the advantage is not only provable but also optimal: it has been shown that Grover's algorithm gives the maximal possible probability of finding the desired element for any number of oracle lookups. Many examples of provable quantum speedups for query problems are based on Grover's algorithm, including Brassard, Høyer, and Tapp's algorithm for finding collisions in two-to-one functions,[60] and Farhi, Goldstone, and Gutmann's algorithm for evaluating NAND trees.[61]

Problems that can be efficiently addressed with Grover's algorithm have the following properties:[62][63]

- There is no searchable structure in the collection of possible answers,

- The number of possible answers to check is the same as the number of inputs to the algorithm, and

- There exists a boolean function that evaluates each input and determines whether it is the correct answer

For problems with all these properties, the running time of Grover's algorithm on a quantum computer scales as the square root of the number of inputs (or elements in the database), as opposed to the linear scaling of classical algorithms. A general class of problems to which Grover's algorithm can be applied[64] is Boolean satisfiability problem, where the database through which the algorithm iterates is that of all possible answers. An example and possible application of this is a password cracker that attempts to guess a password. Breaking symmetric ciphers with this algorithm is of interest to government agencies.[65]

Simulation of quantum systems

Since chemistry and nanotechnology rely on understanding quantum systems, and such systems are impossible to simulate in an efficient manner classically, quantum simulation may be an important application of quantum computing.[66] Quantum simulation could also be used to simulate the behavior of atoms and particles at unusual conditions such as the reactions inside a collider.[67] In June 2023, IBM computer scientists reported that a quantum computer produced better results for a physics problem than a conventional supercomputer.[68][69]

About 2% of the annual global energy output is used for nitrogen fixation to produce ammonia for the Haber process in the agricultural fertilizer industry (even though naturally occurring organisms also produce ammonia). Quantum simulations might be used to understand this process and increase the energy efficiency of production.[70] It is expected that an early use of quantum computing will be modeling that improves the efficiency of the Haber–Bosch process[71] by the mid 2020s[72] although some have predicted it will take longer.[73]

Quantum annealing

Quantum annealing relies on the adiabatic theorem to undertake calculations. A system is placed in the ground state for a simple Hamiltonian, which slowly evolves to a more complicated Hamiltonian whose ground state represents the solution to the problem in question. The adiabatic theorem states that if the evolution is slow enough the system will stay in its ground state at all times through the process. Adiabatic optimization may be helpful for solving computational biology problems.[74]

Machine learning

Since quantum computers can produce outputs that classical computers cannot produce efficiently, and since quantum computation is fundamentally linear algebraic, some express hope in developing quantum algorithms that can speed up machine learning tasks.[75][34]

For example, the quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations, or "HHL Algorithm", named after its discoverers Harrow, Hassidim, and Lloyd, is believed to provide speedup over classical counterparts.[76][34] Some research groups have recently explored the use of quantum annealing hardware for training Boltzmann machines and deep neural networks.[77][78][79]

Deep generative chemistry models emerge as powerful tools to expedite drug discovery. However, the immense size and complexity of the structural space of all possible drug-like molecules pose significant obstacles, which could be overcome in the future by quantum computers. Quantum computers are naturally good for solving complex quantum many-body problems[23] and thus may be instrumental in applications involving quantum chemistry. Therefore, one can expect that quantum-enhanced generative models[80] including quantum GANs[81] may eventually be developed into ultimate generative chemistry algorithms.

Engineering

Challenges

There are a number of technical challenges in building a large-scale quantum computer.[82] Physicist David DiVincenzo has listed these requirements for a practical quantum computer:[83]

- Physically scalable to increase the number of qubits

- Qubits that can be initialized to arbitrary values

- Quantum gates that are faster than decoherence time

- Universal gate set

- Qubits that can be read easily.

Sourcing parts for quantum computers is also very difficult. Superconducting quantum computers, like those constructed by Google and IBM, need helium-3, a nuclear research byproduct, and special superconducting cables made only by the Japanese company Coax Co.[84]

The control of multi-qubit systems requires the generation and coordination of a large number of electrical signals with tight and deterministic timing resolution. This has led to the development of quantum controllers that enable interfacing with the qubits. Scaling these systems to support a growing number of qubits is an additional challenge.[85]

Decoherence

One of the greatest challenges involved with constructing quantum computers is controlling or removing quantum decoherence. This usually means isolating the system from its environment as interactions with the external world cause the system to decohere. However, other sources of decoherence also exist. Examples include the quantum gates, and the lattice vibrations and background thermonuclear spin of the physical system used to implement the qubits. Decoherence is irreversible, as it is effectively non-unitary, and is usually something that should be highly controlled, if not avoided. Decoherence times for candidate systems in particular, the transverse relaxation time T2 (for NMR and MRI technology, also called the dephasing time), typically range between nanoseconds and seconds at low temperature.[86] Currently, some quantum computers require their qubits to be cooled to 20 millikelvin (usually using a dilution refrigerator[87]) in order to prevent significant decoherence.[88] A 2020 study argues that ionizing radiation such as cosmic rays can nevertheless cause certain systems to decohere within milliseconds.[89]

As a result, time-consuming tasks may render some quantum algorithms inoperable, as attempting to maintain the state of qubits for a long enough duration will eventually corrupt the superpositions.[90]

These issues are more difficult for optical approaches as the timescales are orders of magnitude shorter and an often-cited approach to overcoming them is optical pulse shaping. Error rates are typically proportional to the ratio of operating time to decoherence time, hence any operation must be completed much more quickly than the decoherence time.

As described in the threshold theorem, if the error rate is small enough, it is thought to be possible to use quantum error correction to suppress errors and decoherence. This allows the total calculation time to be longer than the decoherence time if the error correction scheme can correct errors faster than decoherence introduces them. An often-cited figure for the required error rate in each gate for fault-tolerant computation is 10−3, assuming the noise is depolarizing.

Meeting this scalability condition is possible for a wide range of systems. However, the use of error correction brings with it the cost of a greatly increased number of required qubits. The number required to factor integers using Shor's algorithm is still polynomial, and thought to be between L and L2, where L is the number of digits in the number to be factored; error correction algorithms would inflate this figure by an additional factor of L. For a 1000-bit number, this implies a need for about 104 bits without error correction.[91] With error correction, the figure would rise to about 107 bits. Computation time is about L2 or about 107 steps and at 1 MHz, about 10 seconds. However, the encoding and error-correction overheads increase the size of a real fault-tolerant quantum computer by several orders of magnitude. Careful estimates[92][93] show that at least 3 million physical qubits would factor 2,048-bit integer in 5 months on a fully error-corrected trapped-ion quantum computer. In terms of the number of physical qubits, to date, this remains the lowest estimate[94] for practically useful integer factorization problem sizing 1,024-bit or larger.

Another approach to the stability-decoherence problem is to create a topological quantum computer with anyons, quasi-particles used as threads, and relying on braid theory to form stable logic gates.[95][96]

Quantum supremacy

Quantum supremacy is a term coined by John Preskill referring to the engineering feat of demonstrating that a programmable quantum device can solve a problem beyond the capabilities of state-of-the-art classical computers.[97][98][99] The problem need not be useful, so some view the quantum supremacy test only as a potential future benchmark.[100]

In October 2019, Google AI Quantum, with the help of NASA, became the first to claim to have achieved quantum supremacy by performing calculations on the Sycamore quantum computer more than 3,000,000 times faster than they could be done on Summit, generally considered the world's fastest computer.[29][101][102] This claim has been subsequently challenged: IBM has stated that Summit can perform samples much faster than claimed,[103][104] and researchers have since developed better algorithms for the sampling problem used to claim quantum supremacy, giving substantial reductions to the gap between Sycamore and classical supercomputers[105][106][107] and even beating it.[108][109][110]

In December 2020, a group at USTC implemented a type of Boson sampling on 76 photons with a photonic quantum computer, Jiuzhang, to demonstrate quantum supremacy.[111][112][113] The authors claim that a classical contemporary supercomputer would require a computational time of 600 million years to generate the number of samples their quantum processor can generate in 20 seconds.[114]

Skepticism

Despite high hopes for quantum computing, significant progress in hardware, and optimism about future applications, as of 2023 quantum computers are "good for ... nothing", per Nature spotlight article.[115] In other words, conventional computers are currently more efficient for practical uses and applications. This state of affairs can be traced to several current and long-term considerations.

- Conventional computer hardware and algorithms are not only optimized for practical tasks, but are still improving rapidly.

- Current quantum computing hardware generates only a limited amount of entanglement before getting overwhelmed by noise and does not rule out practical simulation on conventional computers, possibly except for contrived cases.

- Quantum algorithms provide speedup over conventional algorithms only for some tasks, and matching these tasks with practical applications proved challenging. Some promising tasks and applications require resources far beyond those available today. In particular, processing large amounts of non-quantum data is a challenge for quantum computers.

- If quantum error correction is used to scale quantum computers to practical applications, its overhead may undermine speedup offered by many quantum algorithms.

In particular, building computers with large numbers of qubits may be futile if those qubits are not connected well enough and cannot maintain sufficiently high degree of entanglement for long time. When trying to outperform conventional computers, quantum computing researchers often look for new tasks that can be solved on quantum computers, but this leaves the possibility that efficient non-quantum techniques will be developed in response, as seen for Quantum supremacy demonstrations.

Some researchers have expressed skepticism that scalable quantum computers could ever be built, typically because of the issue of maintaining coherence at large scales, but also for other reasons.

Bill Unruh doubted the practicality of quantum computers in a paper published in 1994.[116] Paul Davies argued that a 400-qubit computer would even come into conflict with the cosmological information bound implied by the holographic principle.[117] Skeptics like Gil Kalai doubt that quantum supremacy will ever be achieved.[118][119][120] Physicist Mikhail Dyakonov has expressed skepticism of quantum computing as follows:

- "So the number of continuous parameters describing the state of such a useful quantum computer at any given moment must be... about 10300... Could we ever learn to control the more than 10300 continuously variable parameters defining the quantum state of such a system? My answer is simple. No, never."[121][122]

Candidates for physical realizations

For physically implementing a quantum computer, many different candidates are being pursued, among them (distinguished by the physical system used to realize the qubits):

- Superconducting quantum computing[123][124] (qubit implemented by the state of nonlinear resonant superconducting circuits containing Josephson junctions)

- Trapped ion quantum computer (qubit implemented by the internal state of trapped ions)

- Neutral atoms in optical lattices (qubit implemented by internal states of neutral atoms trapped in an optical lattice)[125][126]

- Quantum dot computer, spin-based (e.g. the Loss-DiVincenzo quantum computer[127]) (qubit given by the spin states of trapped electrons)

- Quantum dot computer, spatial-based (qubit given by electron position in double quantum dot)[128]

- Quantum computing using engineered quantum wells, which could in principle enable the construction of a quantum computer that operates at room temperature[129][130]

- Coupled quantum wire (qubit implemented by a pair of quantum wires coupled by a quantum point contact)[131][132][133]

- Nuclear magnetic resonance quantum computer (NMRQC) implemented with the nuclear magnetic resonance of molecules in solution, where qubits are provided by nuclear spins within the dissolved molecule and probed with radio waves

- Solid-state NMR Kane quantum computer (qubit realized by the nuclear spin state of phosphorus donors in silicon)

- Vibrational quantum computer (qubits realized by vibrational superpositions in cold molecules)[134]

- Electrons-on-helium quantum computer (qubit is the electron spin)

- Cavity quantum electrodynamics (CQED) (qubit provided by the internal state of trapped atoms coupled to high-finesse cavities)

- Molecular magnet[135] (qubit given by spin states)

- Fullerene-based ESR quantum computer (qubit based on the electronic spin of atoms or molecules encased in fullerenes)[136]

- Nonlinear optical quantum computer (qubits realized by processing states of different modes of light through both linear and nonlinear elements)[137][138]

- Linear optical quantum computer (LOQC) (qubits realized by processing states of different modes of light through linear elements e.g. mirrors, beam splitters and phase shifters).[139] Quantum microprocessor based on laser photonics at room temperature made possible.[140][141]

- Diamond-based quantum computer[142][143][144][145] (qubit realized by the electronic or nuclear spin of nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond)

- Bose-Einstein condensate-based quantum computer[146][147]

- Transistor-based quantum computer (string quantum computers with entrainment of positive holes using an electrostatic trap)

- Rare-earth-metal-ion-doped inorganic crystal based quantum computer[148][149] (qubit realized by the internal electronic state of dopants in optical fibers)

- Metallic-like carbon nanospheres-based quantum computer[150]

The large number of candidates demonstrates that quantum computing, despite rapid progress, is still in its infancy.[151]

Theory

Computability

Any computational problem solvable by a classical computer is also solvable by a quantum computer.[2] Intuitively, this is because it is believed that all physical phenomena, including the operation of classical computers, can be described using quantum mechanics, which underlies the operation of quantum computers.

Conversely, any problem solvable by a quantum computer is also solvable by a classical computer. It is possible to simulate both quantum and classical computers manually with just some paper and a pen, if given enough time. More formally, any quantum computer can be simulated by a Turing machine. In other words, quantum computers provide no additional power over classical computers in terms of computability. This means that quantum computers cannot solve undecidable problems like the halting problem, and the existence of quantum computers does not disprove the Church–Turing thesis.[152]

Complexity

While quantum computers cannot solve any problems that classical computers cannot already solve, it is suspected that they can solve certain problems faster than classical computers. For instance, it is known that quantum computers can efficiently factor integers, while this is not believed to be the case for classical computers.

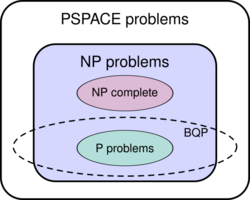

The class of problems that can be efficiently solved by a quantum computer with bounded error is called BQP, for "bounded error, quantum, polynomial time". More formally, BQP is the class of problems that can be solved by a polynomial-time quantum Turing machine with an error probability of at most 1/3. As a class of probabilistic problems, BQP is the quantum counterpart to BPP ("bounded error, probabilistic, polynomial time"), the class of problems that can be solved by polynomial-time probabilistic Turing machines with bounded error.[153] It is known that [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{BPP\subseteq BQP} }[/math] and is widely suspected that [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{BQP\subsetneq BPP} }[/math], which intuitively would mean that quantum computers are more powerful than classical computers in terms of time complexity.[154]

The exact relationship of BQP to P, NP, and PSPACE is not known. However, it is known that [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{P\subseteq BQP \subseteq PSPACE} }[/math]; that is, all problems that can be efficiently solved by a deterministic classical computer can also be efficiently solved by a quantum computer, and all problems that can be efficiently solved by a quantum computer can also be solved by a deterministic classical computer with polynomial space resources. It is further suspected that BQP is a strict superset of P, meaning there are problems that are efficiently solvable by quantum computers that are not efficiently solvable by deterministic classical computers. For instance, integer factorization and the discrete logarithm problem are known to be in BQP and are suspected to be outside of P. On the relationship of BQP to NP, little is known beyond the fact that some NP problems that are believed not to be in P are also in BQP (integer factorization and the discrete logarithm problem are both in NP, for example). It is suspected that [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{NP\nsubseteq BQP} }[/math]; that is, it is believed that there are efficiently checkable problems that are not efficiently solvable by a quantum computer. As a direct consequence of this belief, it is also suspected that BQP is disjoint from the class of NP-complete problems (if an NP-complete problem were in BQP, then it would follow from NP-hardness that all problems in NP are in BQP).[155]

It has been speculated that further advances in physics could lead to even faster computers. For instance, it has been shown that a non-local hidden variable quantum computer based on Bohmian Mechanics could implement a search of an N-item database in at most [math]\displaystyle{ O(\sqrt[3]{N}) }[/math] steps, a slight speedup over Grover's algorithm, which runs in [math]\displaystyle{ O(\sqrt{N}) }[/math] steps. Note, however, that neither search method would allow quantum computers to solve NP-complete problems in polynomial time.[156] Theories of quantum gravity, such as M-theory and loop quantum gravity, may allow even faster computers to be built. However, defining computation in these theories is an open problem due to the problem of time; that is, within these physical theories there is currently no obvious way to describe what it means for an observer to submit input to a computer at one point in time and then receive output at a later point in time.[157][158]

See also

- D-Wave Systems

- Electronic quantum holography

- Glossary of quantum computing

- IARPA

- List of emerging technologies

- List of quantum processors

- Magic state distillation

- Natural computing

- Optical computing

- Quantum bus

- Quantum cognition

- Quantum volume

- Quantum weirdness

- Rigetti Computing

- Supercomputer

- Theoretical computer science

- Unconventional computing

- Valleytronics

Notes

- ↑ The classical logic gates such as AND, OR, NOT, etc., that act on classical bits can be written as matrices, and used in the exact same way as quantum logic gates, as presented in this article. The same rules for series and parallel quantum circuits can then also be used, and also inversion if the classical circuit is reversible.

The equations used for describing NOT and CNOT (below) are the same for both the classical and quantum case (since they are not applied to superposition states).

Unlike quantum gates, classical gates are often not unitary matrices. For example [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{OR} := \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{AND} := \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} }[/math] which are not unitary.

In the classical case, the matrix entries can only be 0s and 1s, while for quantum computers this is generalized to complex numbers.[39] - ↑ The standard basis is also the "computational basis".[40]

- ↑ In general, probability amplitudes are complex numbers.

References

- ↑ Russell, John (January 10, 2019). "IBM Quantum Update: Q System One Launch, New Collaborators, and QC Center Plans" (in en-US). https://www.hpcwire.com/2019/01/10/ibm-quantum-update-q-system-one-launch-new-collaborators-and-qc-center-plans/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Aaronson 2013, p. 132.

- ↑ Bhatta, Varun S. (2020-05-10). "Plurality of Wave–Particle Duality" (in en-US). Current Science 118 (9): 1365. doi:10.18520/cs/v118/i9/1365-1374. ISSN 0011-3891. https://wwwops.currentscience.ac.in/Volumes/118/09/1365.pdf.

- ↑ Ceruzzi, Paul E. (2012) (in en-US). Computing: A Concise History. Cambridge, Massachusetts. pp. 3,46. ISBN 978-0-262-31038-3. OCLC 796812982.

- ↑ Hodges, Andrew (2014) (in en-US). Alan Turing: The Enigma. Princeton University Press. p. xviii. ISBN 9780691164724.

- ↑ Mårtensson-Pendrill, Ann-Marie (2006-11-01). "The Manhattan project—a part of physics history" (in en-US). Physics Education 41 (6): 493–501. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/41/6/001. ISSN 0031-9120. Bibcode: 2006PhyEd..41..493M.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Benioff, Paul (1980). "The computer as a physical system: A microscopic quantum mechanical Hamiltonian model of computers as represented by Turing machines". Journal of Statistical Physics 22 (5): 563–591. doi:10.1007/bf01011339. Bibcode: 1980JSP....22..563B.

- ↑ Buluta, Iulia; Nori, Franco (2009-10-02). "Quantum Simulators" (in en). Science 326 (5949): 108–111. doi:10.1126/science.1177838. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19797653. Bibcode: 2009Sci...326..108B.

- ↑ Manin, Yu. I. (1980) (in ru). Vychislimoe i nevychislimoe. Sov.Radio. pp. 13–15. http://publ.lib.ru/ARCHIVES/M/MANIN_Yuriy_Ivanovich/Manin_Yu.I._Vychislimoe_i_nevychislimoe.(1980).%5bdjv-fax%5d.zip. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ↑ Feynman, Richard (June 1982). "Simulating Physics with Computers". International Journal of Theoretical Physics 21 (6/7): 467–488. doi:10.1007/BF02650179. Bibcode: 1982IJTP...21..467F. https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~christos/classics/Feynman.pdf. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ↑ Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 214.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Bennett, Charles H.; Brassard, Gilles (December 1984). "Quantum cryptography: Public key distribution and coin tossing" (in en). IEEE International Conference on Computers, Systems & Signal Processing. Bangalore. pp. 175–179. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2014.05.025.

- ↑ Brassard, G. (2005). "Brief history of quantum cryptography: a personal perspective". IEEE Information Theory Workshop on Theory and Practice in Information-Theoretic Security, 2005. (Awaji Island, Japan: IEEE): 19–23. doi:10.1109/ITWTPI.2005.1543949. ISBN 978-0-7803-9491-9. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1543949.

- ↑ Deutsch, D. (1985-07-08). "Quantum theory, the Church–Turing principle and the universal quantum computer" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 400 (1818): 97–117. doi:10.1098/rspa.1985.0070. ISSN 0080-4630. Bibcode: 1985RSPSA.400...97D.

- ↑ Bernstein, Ethan; Vazirani, Umesh (1993). "Quantum complexity theory" (in en). Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing – STOC '93 (San Diego, California, United States: ACM Press): 11–20. doi:10.1145/167088.167097. ISBN 978-0-89791-591-5. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=167088.167097.

- ↑ Simon, D. R. (1994). "On the power of quantum computation". Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA: IEEE Comput. Soc. Press): 116–123. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1994.365701. ISBN 978-0-8186-6580-6. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/365701.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 30-32.

- ↑ Shor 1994.

- ↑ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019, p. 15.

- ↑ Grover, Lov K. (1996). "A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search" (in en). ACM symposium on Theory of computing. Philadelphia: ACM Press. pp. 212–219. doi:10.1145/237814.237866. ISBN 978-0-89791-785-8.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Lloyd, Seth (1996-08-23). "Universal Quantum Simulators". Science 273 (5278): 1073–1078. doi:10.1126/science.273.5278.1073. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 8688088. Bibcode: 1996Sci...273.1073L.

- ↑ Cao, Yudong; Romero, Jonathan; Olson, Jonathan P.; Degroote, Matthias; Johnson, Peter D. et al. (2019-10-09). "Quantum Chemistry in the Age of Quantum Computing" (in en-US). Chemical Reviews 119 (19): 10856–10915. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00803. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 31469277.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019, pp. 164-169.

- ↑ Chuang, Isaac L.; Gershenfeld, Neil; Kubinec, Markdoi (April 1998). "Experimental Implementation of Fast Quantum Searching". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society) 80 (15): 3408–3411. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.3408. Bibcode: 1998PhRvL..80.3408C.

- ↑ Holton, William Coffeen. "quantum computer". Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/quantum-computer.

- ↑ Gibney, Elizabeth (2019-10-23). "Hello quantum world! Google publishes landmark quantum supremacy claim" (in en). Nature 574 (7779): 461–462. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03213-z. PMID 31645740. Bibcode: 2019Natur.574..461G.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Lay summary: Martinis, John; Boixo, Sergio (October 23, 2019). "Quantum Supremacy Using a Programmable Superconducting Processor". Nature (Google AI) 574 (7779): 505–510. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1666-5. PMID 31645734. Bibcode: 2019Natur.574..505A. https://ai.googleblog.com/2019/10/quantum-supremacy-using-programmable.html. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

• Journal article: Arute, Frank; Arya, Kunal; Babbush, Ryan; Bacon, Dave; Bardin, Joseph C. et al. (October 23, 2019). "Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor". Nature 574 (7779): 505–510. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1666-5. PMID 31645734. Bibcode: 2019Natur.574..505A. - ↑ Aaronson, Scott (2019-10-30). "Opinion | Why Google's Quantum Supremacy Milestone Matters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/opinion/google-quantum-computer-sycamore.html.

- ↑ Pednault, Edwin (22 October 2019). "On 'Quantum Supremacy'". https://www.ibm.com/blogs/research/2019/10/on-quantum-supremacy/.

- ↑ Pan, Feng; Zhang, Pan (2021-03-04). "Simulating the Sycamore quantum supremacy circuits". arXiv:2103.03074 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 481.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Preskill, John (6 August 2018). "Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond". Quantum 2: 79. doi:10.22331/q-2018-08-06-79. Bibcode: 2018Quant...2...79P.

- ↑ Gibney, Elizabeth (2 October 2019). "Quantum gold rush: the private funding pouring into quantum start-ups". Nature 574 (7776): 22–24. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02935-4. PMID 31578480. Bibcode: 2019Natur.574...22G.

- ↑ Rodrigo, Chris Mills (12 February 2020). "Trump budget proposal boosts funding for artificial intelligence, quantum computing" (in en-US). The Hill. https://thehill.com/policy/technology/482402-trump-budget-proposal-boosts-funding-for-artificial-intelligence-quantum.

- ↑ Biondi, Matteo; Heid, Anna; Henke, Nicolaus; Mohr, Niko; Pautasso, Lorenzo; Ostojic, Ivan; Wester, Linde; Zemmel, Rodney (14 December 2021). "Quantum computing use cases are getting real—what you need to know" (in en-US). https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/quantum-computing-use-cases-are-getting-real-what-you-need-to-know.

- ↑ Nielsen & Chuang 2010.

- ↑ Yanofsky, Noson S.; Mannucci, Mirco (2013). Quantum computing for computer scientists. Cambridge University Press. pp. 144–147, 158–169. ISBN 978-0-521-87996-5.

- ↑ Mermin 2007, p. 18.

- ↑ Das, A.; Chakrabarti, B. K. (2008). "Quantum Annealing and Analog Quantum Computation". Rev. Mod. Phys. 80 (3): 1061–1081. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1061. Bibcode: 2008RvMP...80.1061D.

- ↑ Nayak, Chetan; Simon, Steven; Stern, Ady; Das Sarma, Sankar (2008). "Nonabelian Anyons and Quantum Computation". Reviews of Modern Physics 80 (3): 1083–1159. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1083. Bibcode: 2008RvMP...80.1083N.

- ↑ Chi-Chih Yao, A. (1993). "Quantum circuit complexity". Proceedings of 1993 IEEE 34th Annual Foundations of Computer Science: 352–361. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1993.366852. ISBN 0-8186-4370-6. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/366852.

- ↑ Raussendorf, Robert; Browne, Daniel E.; Briegel, Hans J. (2003-08-25). "Measurement-based quantum computation on cluster states". Physical Review A 68 (2): 022312. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.68.022312. Bibcode: 2003PhRvA..68b2312R.

- ↑ Aharonov, Dorit; van Dam, Wim; Kempe, Julia; Landau, Zeph; Lloyd, Seth; Regev, Oded (2008-01-01). "Adiabatic Quantum Computation Is Equivalent to Standard Quantum Computation". SIAM Review 50 (4): 755–787. doi:10.1137/080734479. ISSN 0036-1445. Bibcode: 2008SIAMR..50..755A.

- ↑ Freedman, Michael H.; Larsen, Michael; Wang, Zhenghan (2002-06-01). "A Modular Functor Which is Universal for Quantum Computation". Communications in Mathematical Physics 227 (3): 605–622. doi:10.1007/s002200200645. ISSN 0010-3616. Bibcode: 2002CMaPh.227..605F.

- ↑ Pirandola, S.; Andersen, U. L.; Banchi, L.; Berta, M.; Bunandar, D.; Colbeck, R.; Englund, D.; Gehring, T. et al. (2020-12-14). "Advances in quantum cryptography" (in en). Advances in Optics and Photonics 12 (4): 1017. doi:10.1364/AOP.361502. ISSN 1943-8206.

- ↑ Xu, Feihu; Ma, Xiongfeng; Zhang, Qiang; Lo, Hoi-Kwong; Pan, Jian-Wei (2020-05-26). "Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices". Reviews of Modern Physics 92 (2): 025002-3. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.92.025002.

- ↑ Xu, Guobin; Mao, Jianzhou; Sakk, Eric; Wang, Shuangbao Paul (2023-03-22). "An Overview of Quantum-Safe Approaches: Quantum Key Distribution and Post-Quantum Cryptography". IEEE. p. 3. doi:10.1109/CISS56502.2023.10089619. ISBN 978-1-6654-5181-9.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Jordan, Stephen (14 October 2022). "Quantum Algorithm Zoo". http://math.nist.gov/quantum/zoo/.

- ↑ Aaronson, Scott; Arkhipov, Alex (2011-06-06). "The computational complexity of linear optics" (in en). San Jose, California: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 333–342. doi:10.1145/1993636.1993682. ISBN 978-1-4503-0691-1.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 42.

- ↑ Lenstra, Arjen K. (2000). "Integer Factoring". Designs, Codes and Cryptography 19 (2/3): 101–128. doi:10.1023/A:1008397921377. http://sage.math.washington.edu/edu/124/misc/arjen_lenstra_factoring.pdf.

- ↑ Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 216.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Bernstein, Daniel J. (2009). "Introduction to post-quantum cryptography". Post-Quantum Cryptography. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 1–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88702-7_1. ISBN 978-3-540-88701-0.

- ↑ See also pqcrypto.org, a bibliography maintained by Daniel J. Bernstein and Tanja Lange on cryptography not known to be broken by quantum computing.

- ↑ McEliece, R. J. (January 1978). "A Public-Key Cryptosystem Based On Algebraic Coding Theory". DSNPR 44: 114–116. Bibcode: 1978DSNPR..44..114M. http://ipnpr.jpl.nasa.gov/progress_report2/42-44/44N.PDF.

- ↑ Kobayashi, H.; Gall, F. L. (2006). "Dihedral Hidden Subgroup Problem: A Survey". Information and Media Technologies 1 (1): 178–185. doi:10.2197/ipsjdc.1.470.

- ↑ Bennett, Charles H.; Bernstein, Ethan; Brassard, Gilles; Vazirani, Umesh (October 1997). "Strengths and Weaknesses of Quantum Computing". SIAM Journal on Computing 26 (5): 1510–1523. doi:10.1137/s0097539796300933. Bibcode: 1997quant.ph..1001B.

- ↑ Brassard, Gilles; Høyer, Peter; Tapp, Alain (2016). "Quantum Algorithm for the Collision Problem". in Kao, Ming-Yang (in en). Encyclopedia of Algorithms. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 1662–1664. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2864-4_304. ISBN 978-1-4939-2864-4.

- ↑ Farhi, Edward; Goldstone, Jeffrey; Gutmann, Sam (23 December 2008). "A Quantum Algorithm for the Hamiltonian NAND Tree" (in EN). Theory of Computing 4 (1): 169–190. doi:10.4086/toc.2008.v004a008. ISSN 1557-2862.

- ↑ Williams, Colin P. (2011). Explorations in Quantum Computing. Springer. pp. 242–244. ISBN 978-1-84628-887-6.

- ↑ Grover, Lov (29 May 1996). "A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search". arXiv:quant-ph/9605043.

- ↑ Ambainis, Ambainis (June 2004). "Quantum search algorithms". ACM SIGACT News 35 (2): 22–35. doi:10.1145/992287.992296. Bibcode: 2005quant.ph..4012A.

- ↑ Rich, Steven; Gellman, Barton (1 February 2014). "NSA seeks to build quantum computer that could crack most types of encryption". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/nsa-seeks-to-build-quantum-computer-that-could-crack-most-types-of-encryption/2014/01/02/8fff297e-7195-11e3-8def-a33011492df2_story.html.

- ↑ Norton, Quinn (15 February 2007). "The Father of Quantum Computing". Wired. http://archive.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2007/02/72734.

- ↑ Ambainis, Andris (Spring 2014). "What Can We Do with a Quantum Computer?". Institute for Advanced Study. http://www.ias.edu/ias-letter/ambainis-quantum-computing.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (14 June 2023). "Quantum Computing Advance Begins New Era, IBM Says – A quantum computer came up with better answers to a physics problem than a conventional supercomputer.". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. https://archive.is/XBFmz. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ Kim, Youngseok (14 June 2023). "Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance". Nature 618 (7965): 500–505. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06096-3. PMID 37316724.

- ↑ Morello, Andrea (21 November 2018). Lunch & Learn: Quantum Computing. Sibos TV. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 4 February 2021 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Ruane, Jonathan; McAfee, Andrew; Oliver, William D. (2022-01-01). "Quantum Computing for Business Leaders". Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. https://hbr.org/2022/01/quantum-computing-for-business-leaders.

- ↑ Budde, Florian; Volz, Daniel (July 12, 2019). "Quantum computing and the chemical industry | McKinsey". McKinsey and Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/chemicals/our-insights/the-next-big-thing-quantum-computings-potential-impact-on-chemicals.

- ↑ Bourzac, Katherine (October 30, 2017). "Chemistry is quantum computing's killer app". American Chemical Society. https://cen.acs.org/articles/95/i43/Chemistry-quantum-computings-killer-app.html.

- ↑ Outeiral, Carlos; Strahm, Martin; Morris, Garrett; Benjamin, Simon; Deane, Charlotte; Shi, Jiye (2021). "The prospects of quantum computing in computational molecular biology". WIREs Computational Molecular Science 11. doi:10.1002/wcms.1481.

- ↑ Biamonte, Jacob; Wittek, Peter; Pancotti, Nicola; Rebentrost, Patrick; Wiebe, Nathan; Lloyd, Seth (September 2017). "Quantum machine learning" (in en). Nature 549 (7671): 195–202. doi:10.1038/nature23474. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28905917. Bibcode: 2017Natur.549..195B.

- ↑ Harrow, Aram; Hassidim, Avinatan; Lloyd, Seth (2009). "Quantum algorithm for solving linear systems of equations". Physical Review Letters 103 (15): 150502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.150502. PMID 19905613. Bibcode: 2009PhRvL.103o0502H.

- ↑ Benedetti, Marcello; Realpe-Gómez, John; Biswas, Rupak; Perdomo-Ortiz, Alejandro (9 August 2016). "Estimation of effective temperatures in quantum annealers for sampling applications: A case study with possible applications in deep learning". Physical Review A 94 (2): 022308. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.94.022308. Bibcode: 2016PhRvA..94b2308B.

- ↑ Ajagekar, Akshay; You, Fengqi (5 December 2020). "Quantum computing assisted deep learning for fault detection and diagnosis in industrial process systems" (in en). Computers & Chemical Engineering 143: 107119. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2020.107119. ISSN 0098-1354.

- ↑ Ajagekar, Akshay; You, Fengqi (2021-12-01). "Quantum computing based hybrid deep learning for fault diagnosis in electrical power systems" (in en). Applied Energy 303: 117628. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117628. ISSN 0306-2619.

- ↑ Gao, Xun; Anschuetz, Eric R.; Wang, Sheng-Tao; Cirac, J. Ignacio; Lukin, Mikhail D. (2022). "Enhancing Generative Models via Quantum Correlations". Physical Review X 12 (2): 021037. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.12.021037. Bibcode: 2022PhRvX..12b1037G.

- ↑ Li, Junde; Topaloglu, Rasit; Ghosh, Swaroop (9 January 2021). "Quantum Generative Models for Small Molecule Drug Discovery". arXiv:2101.03438 [cs.ET].

- ↑ Dyakonov, Mikhail (15 November 2018). "The Case Against Quantum Computing". IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/hardware/the-case-against-quantum-computing.

- ↑ DiVincenzo, David P. (13 April 2000). "The Physical Implementation of Quantum Computation". Fortschritte der Physik 48 (9–11): 771–783. doi:10.1002/1521-3978(200009)48:9/11<771::AID-PROP771>3.0.CO;2-E. Bibcode: 2000ForPh..48..771D.

- ↑ Giles, Martin (January 17, 2019). "We'd have more quantum computers if it weren't so hard to find the damn cables" (in en-US). MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/612760/quantum-computers-component-shortage/.

- ↑ "A cryogenic CMOS chip for generating control signals for multiple qubits". Nature Electronics 4 (4): 64–70. 2021. doi:10.1038/s41928-020-00528-y. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41928-020-00528-y.

- ↑ DiVincenzo, David P. (1995). "Quantum Computation". Science 270 (5234): 255–261. doi:10.1126/science.270.5234.255. Bibcode: 1995Sci...270..255D.

- ↑ Zu, H.; Dai, W.; de Waele, A.T.A.M. (2022). "Development of Dilution refrigerators – A review". Cryogenics 121. doi:10.1016/j.cryogenics.2021.103390. ISSN 0011-2275. Bibcode: 2022Cryo..121....1Z.

- ↑ Jones, Nicola (19 June 2013). "Computing: The quantum company". Nature 498 (7454): 286–288. doi:10.1038/498286a. PMID 23783610. Bibcode: 2013Natur.498..286J.

- ↑ Vepsäläinen, Antti P.; Karamlou, Amir H.; Orrell, John L.; Dogra, Akshunna S.; Loer, Ben et al. (August 2020). "Impact of ionizing radiation on superconducting qubit coherence" (in en). Nature 584 (7822): 551–556. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2619-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32848227. Bibcode: 2020Natur.584..551V. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2619-8.

- ↑ Amy, Matthew; Matteo, Olivia; Gheorghiu, Vlad; Mosca, Michele; Parent, Alex; Schanck, John (30 November 2016). "Estimating the cost of generic quantum pre-image attacks on SHA-2 and SHA-3". arXiv:1603.09383 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Dyakonov, M. I. (14 October 2006). "Is Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation Really Possible?". Future Trends in Microelectronics. Up the Nano Creek: 4–18. Bibcode: 2006quant.ph.10117D.

- ↑ Ahsan, Muhammad (2015) (in en-US). Architecture Framework for Trapped-ion Quantum Computer based on Performance Simulation Tool. OCLC 923881411. http://worldcat.org/oclc/923881411.

- ↑ Ahsan, Muhammad; Meter, Rodney Van; Kim, Jungsang (2016-12-28). "Designing a Million-Qubit Quantum Computer Using a Resource Performance Simulator". ACM Journal on Emerging Technologies in Computing Systems 12 (4): 39:1–39:25. doi:10.1145/2830570. ISSN 1550-4832.

- ↑ Gidney, Craig; Ekerå, Martin (2021-04-15). "How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits". Quantum 5: 433. doi:10.22331/q-2021-04-15-433. ISSN 2521-327X. Bibcode: 2021Quant...5..433G.

- ↑ "Topological quantum computation". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 40 (1): 31–38. 2003. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-02-00964-3.

- ↑ Monroe, Don (1 October 2008). "Anyons: The breakthrough quantum computing needs?". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/channel/fundamentals/mg20026761.700-anyons-the-breakthrough-quantum-computing-needs.html.

- ↑ Preskill, John (2012-03-26). "Quantum computing and the entanglement frontier". arXiv:1203.5813 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Preskill, John (2018-08-06). "Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond". Quantum 2: 79. doi:10.22331/q-2018-08-06-79. Bibcode: 2018Quant...2...79P.

- ↑ Boixo, Sergio; Isakov, Sergei V.; Smelyanskiy, Vadim N.; Babbush, Ryan; Ding, Nan et al. (2018). "Characterizing Quantum Supremacy in Near-Term Devices". Nature Physics 14 (6): 595–600. doi:10.1038/s41567-018-0124-x. Bibcode: 2018NatPh..14..595B.

- ↑ Savage, Neil (5 July 2017). "Quantum Computers Compete for "Supremacy"". Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/quantum-computers-compete-for-supremacy/.

- ↑ Giles, Martin (September 20, 2019). "Google researchers have reportedly achieved 'quantum supremacy'" (in en). https://www.technologyreview.com/f/614416/google-researchers-have-reportedly-achieved-quantum-supremacy/.

- ↑ Tavares, Frank (2019-10-23). "Google and NASA Achieve Quantum Supremacy" (in en-US). http://www.nasa.gov/feature/ames/quantum-supremacy.

- ↑ Pednault, Edwin; Gunnels, John A.; Nannicini, Giacomo; Horesh, Lior; Wisnieff, Robert (2019-10-22). "Leveraging Secondary Storage to Simulate Deep 54-qubit Sycamore Circuits". arXiv:1910.09534 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Cho, Adrian (2019-10-23). "IBM casts doubt on Google's claims of quantum supremacy". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaz6080. ISSN 0036-8075. https://www.science.org/content/article/ibm-casts-doubt-googles-claims-quantum-supremacy.

- ↑ Liu, Yong (Alexander); Liu, Xin (Lucy); Li, Fang (Nancy); Fu, Haohuan; Yang, Yuling et al. (2021-11-14). "Closing the "quantum supremacy" gap: achieving real-time simulation of a random quantum circuit using a new Sunway supercomputer". Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis. SC '21 (New York, New York: Association for Computing Machinery): 1–12. doi:10.1145/3458817.3487399. ISBN 978-1-4503-8442-1.

- ↑ Bulmer, Jacob F. F.; Bell, Bryn A.; Chadwick, Rachel S.; Jones, Alex E.; Moise, Diana et al. (2022-01-28). "The boundary for quantum advantage in Gaussian boson sampling" (in en). Science Advances 8 (4): eabl9236. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abl9236. ISSN 2375-2548. PMID 35080972. Bibcode: 2022SciA....8.9236B.

- ↑ McCormick, Katie (2022-02-10). "Race Not Over Between Classical and Quantum Computers" (in en). Physics 15: 19. doi:10.1103/Physics.15.19. Bibcode: 2022PhyOJ..15...19M. https://physics.aps.org/articles/v15/19.

- ↑ Pan, Feng; Chen, Keyang; Zhang, Pan (2022). "Solving the Sampling Problem of the Sycamore Quantum Circuits". Physical Review Letters 129 (9): 090502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.129.090502. PMID 36083655. Bibcode: 2022PhRvL.129i0502P.

- ↑ Cho, Adrian (2022-08-02). Ordinary computers can beat Google's quantum computer after all. doi:10.1126/science.ade2364. https://www.science.org/content/article/ordinary-computers-can-beat-google-s-quantum-computer-after-all.

- ↑ "Google's 'quantum supremacy' usurped by researchers using ordinary supercomputer" (in en-US). 5 August 2022. https://social.techcrunch.com/2022/08/05/googles-quantum-supremacy-usurped-by-researchers-using-ordinary-supercomputer/.

- ↑ Ball, Philip (2020-12-03). "Physicists in China challenge Google's 'quantum advantage'" (in en). Nature 588 (7838): 380. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03434-7. PMID 33273711. Bibcode: 2020Natur.588..380B.

- ↑ Garisto, Daniel. "Light-based Quantum Computer Exceeds Fastest Classical Supercomputers" (in en). https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/light-based-quantum-computer-exceeds-fastest-classical-supercomputers/.

- ↑ Conover, Emily (2020-12-03). "The new light-based quantum computer Jiuzhang has achieved quantum supremacy" (in en-US). https://www.sciencenews.org/article/new-light-based-quantum-computer-jiuzhang-supremacy.

- ↑ Zhong, Han-Sen; Wang, Hui; Deng, Yu-Hao; Chen, Ming-Cheng; Peng, Li-Chao et al. (2020-12-03). "Quantum computational advantage using photons" (in en). Science 370 (6523): 1460–1463. doi:10.1126/science.abe8770. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33273064. Bibcode: 2020Sci...370.1460Z.

- ↑ Brooks, Michael (24 May 2023). "Quantum computers: what are they good for?". https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01692-9.

- ↑ Unruh, Bill (1995). "Maintaining coherence in Quantum Computers". Physical Review A 51 (2): 992–997. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.51.992. PMID 9911677. Bibcode: 1995PhRvA..51..992U.

- ↑ Davies, Paul (6 March 2007). "The implications of a holographic universe for quantum information science and the nature of physical law". arXiv:quant-ph/0703041.

- ↑ Regan, K. W. (23 April 2016). "Quantum Supremacy and Complexity". https://rjlipton.wordpress.com/2016/04/22/quantum-supremacy-and-complexity/.

- ↑ Kalai, Gil (May 2016). "The Quantum Computer Puzzle". Notices of the AMS 63 (5): 508–516. https://www.ams.org/journals/notices/201605/rnoti-p508.pdf.

- ↑ Rinott, Yosef; Shoham, Tomer; Kalai, Gil (2021-07-13). "Statistical Aspects of the Quantum Supremacy Demonstration". arXiv:2008.05177 [quant-ph].

- ↑ Dyakonov, Mikhail (15 November 2018). "The Case Against Quantum Computing". https://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/hardware/the-case-against-quantum-computing.

- ↑ Dyakonov, Mikhail (24 March 2020). Will We Ever Have a Quantum Computer?. Springer. ISBN 9783030420185. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030420185. Retrieved 22 May 2020.[page needed]

- ↑ Clarke, John; Wilhelm, Frank K. (18 June 2008). "Superconducting quantum bits". Nature 453 (7198): 1031–1042. doi:10.1038/nature07128. PMID 18563154. Bibcode: 2008Natur.453.1031C. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/7ee1053ce63f33a62f2ea555547c514ce5f21054.

- ↑ Kaminsky, William M.; Lloyd, Seth; Orlando, Terry P. (12 March 2004). "Scalable Superconducting Architecture for Adiabatic Quantum Computation". arXiv:quant-ph/0403090. Bibcode: 2004quant.ph..3090K

- ↑ Khazali, Mohammadsadegh; Mølmer, Klaus (11 June 2020). "Fast Multiqubit Gates by Adiabatic Evolution in Interacting Excited-State Manifolds of Rydberg Atoms and Superconducting Circuits". Physical Review X 10 (2): 021054. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.10.021054. Bibcode: 2020PhRvX..10b1054K.

- ↑ Henriet, Loic; Beguin, Lucas; Signoles, Adrien; Lahaye, Thierry; Browaeys, Antoine; Reymond, Georges-Olivier; Jurczak, Christophe (22 June 2020). "Quantum computing with neutral atoms". Quantum 4: 327. doi:10.22331/q-2020-09-21-327. Bibcode: 2020Quant...4..327H.

- ↑ Imamog¯lu, A.; Awschalom, D. D.; Burkard, G.; DiVincenzo, D. P.; Loss, D.; Sherwin, M.; Small, A. (15 November 1999). "Quantum Information Processing Using Quantum Dot Spins and Cavity QED". Physical Review Letters 83 (20): 4204–4207. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.4204. Bibcode: 1999PhRvL..83.4204I.

- ↑ Fedichkin, L.; Yanchenko, M.; Valiev, K. A. (June 2000). "Novel coherent quantum bit using spatial quantization levels in semiconductor quantum dot". Quantum Computers and Computing 1: 58. Bibcode: 2000quant.ph..6097F.

- ↑ Ivády, Viktor; Davidsson, Joel; Delegan, Nazar; Falk, Abram L.; Klimov, Paul V. et al. (6 December 2019). "Stabilization of point-defect spin qubits by quantum wells". Nature Communications 10 (1): 5607. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13495-6. PMID 31811137. Bibcode: 2019NatCo..10.5607I.

- ↑ "Scientists Discover New Way to Get Quantum Computing to Work at Room Temperature". interestingengineering.com. 24 April 2020. https://interestingengineering.com/scientists-discover-new-way-to-get-quantum-computing-to-work-at-room-temperature.

- ↑ Bertoni, A.; Bordone, P.; Brunetti, R.; Jacoboni, C.; Reggiani, S. (19 June 2000). "Quantum Logic Gates based on Coherent Electron Transport in Quantum Wires". Physical Review Letters 84 (25): 5912–5915. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.5912. PMID 10991086. Bibcode: 2000PhRvL..84.5912B.

- ↑ Ionicioiu, Radu; Amaratunga, Gehan; Udrea, Florin (20 January 2001). "Quantum Computation with Ballistic Electrons". International Journal of Modern Physics B 15 (2): 125–133. doi:10.1142/S0217979201003521. Bibcode: 2001IJMPB..15..125I.

- ↑ Ramamoorthy, A; Bird, J. P.; Reno, J. L. (11 July 2007). "Using split-gate structures to explore the implementation of a coupled-electron-waveguide qubit scheme". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 19 (27): 276205. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/19/27/276205. Bibcode: 2007JPCM...19A6205R.

- ↑ Berrios, Eduardo; Gruebele, Martin; Shyshlov, Dmytro; Wang, Lei; Babikov, Dmitri (2012). "High fidelity quantum gates with vibrational qubits". Journal of Chemical Physics 116 (46): 11347–11354. doi:10.1021/jp3055729. PMID 22803619. Bibcode: 2012JPCA..11611347B.

- ↑ Leuenberger, Michael N.; Loss, Daniel (April 2001). "Quantum computing in molecular magnets". Nature 410 (6830): 789–793. doi:10.1038/35071024. PMID 11298441. Bibcode: 2001Natur.410..789L.

- ↑ Harneit, Wolfgang (27 February 2002). "Fullerene-based electron-spin quantum computer". Physical Review A 65 (3): 032322. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.65.032322. Bibcode: 2002PhRvA..65c2322H. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257976907.

- ↑ Igeta, K.; Yamamoto, Y. (1988). "Quantum mechanical computers with single atom and photon fields". International Quantum Electronics Conference. https://www.osapublishing.org/abstract.cfm?uri=IQEC-1988-TuI4.

- ↑ Chuang, I. L.; Yamamoto, Y. (1995). "Simple quantum computer". Physical Review A 52 (5): 3489–3496. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.3489. PMID 9912648. Bibcode: 1995PhRvA..52.3489C.

- ↑ Knill, G. J.; Laflamme, R.; Milburn, G. J. (2001). "A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics". Nature 409 (6816): 46–52. doi:10.1038/35051009. PMID 11343107. Bibcode: 2001Natur.409...46K. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/054b680165a7325569ca6e63028ca9cee7f3ac9a.

- ↑ "Indian scientist among those who made building blocks of quantum computer" (in en). 2023-05-06. https://www.deccanherald.com/business/technology/indian-scientist-among-those-who-made-building-blocks-of-quantum-computer-1216384.html.

- ↑ "Traditional hardware can match Google's quantum computer performance: Researchers" (in en). 2022-08-07. https://www.deccanherald.com/science-and-environment/traditional-hardware-can-match-googles-quantum-computer-performance-researchers-1134055.html.

- ↑ Nizovtsev, A. P. (August 2005). "A quantum computer based on NV centers in diamond: Optically detected nutations of single electron and nuclear spins". Optics and Spectroscopy 99 (2): 248–260. doi:10.1134/1.2034610. Bibcode: 2005OptSp..99..233N. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/a7598ca24265e5537f14dc61b7c3a1d5b5953162.

- ↑ Dutt, M. V. G.; Childress, L.; Jiang, L.; Togan, E.; Maze, J. et al. (1 June 2007). "Quantum Register Based on Individual Electronic and Nuclear Spin Qubits in Diamond". Science 316 (5829): 1312–1316. doi:10.1126/science.1139831. PMID 17540898. Bibcode: 2007Sci...316.....D.

- ↑ Baron, David (June 7, 2007). "At room temperature, carbon-13 nuclei in diamond create stable, controllable quantum register". The Harvard Gazette, FAS Communications. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2007/06/single-spinning-nuclei-in-diamond-offer-a-stable-quantum-computing-building-block/.

- ↑ Neumann, P.; Mizuochi, N.; Rempp, F.; Hemmer, P.; Watanabe, H. et al. (6 June 2008). "Multipartite Entanglement Among Single Spins in Diamond". Science 320 (5881): 1326–1329. doi:10.1126/science.1157233. PMID 18535240. Bibcode: 2008Sci...320.1326N.

- ↑ Anderlini, Marco; Lee, Patricia J.; Brown, Benjamin L.; Sebby-Strabley, Jennifer; Phillips, William D.; Porto, J. V. (July 2007). "Controlled exchange interaction between pairs of neutral atoms in an optical lattice". Nature 448 (7152): 452–456. doi:10.1038/nature06011. PMID 17653187. Bibcode: 2007Natur.448..452A.

- ↑ "Thousands of Atoms Swap 'Spins' with Partners in Quantum Square Dance". NIST. January 8, 2018. https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2007/07/thousands-atoms-swap-spins-partners-quantum-square-dance.

- ↑ Ohlsson, N.; Mohan, R. K.; Kröll, S. (1 January 2002). "Quantum computer hardware based on rare-earth-ion-doped inorganic crystals". Opt. Commun. 201 (1–3): 71–77. doi:10.1016/S0030-4018(01)01666-2. Bibcode: 2002OptCo.201...71O.

- ↑ Longdell, J. J.; Sellars, M. J.; Manson, N. B. (23 September 2004). "Demonstration of conditional quantum phase shift between ions in a solid". Phys. Rev. Lett. 93 (13): 130503. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.130503. PMID 15524694. Bibcode: 2004PhRvL..93m0503L.

- ↑ Náfrádi, Bálint; Choucair, Mohammad; Dinse, Klaus-Peter; Forró, László (18 July 2016). "Room temperature manipulation of long lifetime spins in metallic-like carbon nanospheres". Nature Communications 7 (1): 12232. doi:10.1038/ncomms12232. PMID 27426851. Bibcode: 2016NatCo...712232N.

- ↑ Naveh, Yehuda. "Council Post: Quantum Software Development Is Still In Its Infancy" (in en). https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2021/06/23/quantum-software-development-is-still-in-its-infancy/.

- ↑ Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 126.

- ↑ Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 41.

- ↑ Nielsen & Chuang 2010, p. 201.

- ↑ Bernstein, Ethan; Vazirani, Umesh (1997). "Quantum Complexity Theory". SIAM Journal on Computing 26 (5): 1411–1473. doi:10.1137/S0097539796300921. http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~vazirani/bv.ps.

- ↑ Aaronson, Scott. "Quantum Computing and Hidden Variables". http://www.scottaaronson.com/papers/qchvpra.pdf.

- ↑ Aaronson, Scott (2005). "NP-complete Problems and Physical Reality". ACM SIGACT News 2005. Bibcode: 2005quant.ph..2072A. See section 7 "Quantum Gravity": "[...] to anyone who wants a test or benchmark for a favorite quantum gravity theory,[author's footnote: That is, one without all the bother of making numerical predictions and comparing them to observation] let me humbly propose the following: can you define Quantum Gravity Polynomial-Time? [...] until we can say what it means for a 'user' to specify an 'input' and 'later' receive an 'output'—there is no such thing as computation, not even theoretically." (emphasis in original)

- ↑ "D-Wave Systems sells its first Quantum Computing System to Lockheed Martin Corporation". D-Wave. 25 May 2011. http://www.dwavesys.com/en/pressreleases.html#lm_2011.

Further reading

Textbooks

- Aaronson, Scott (2013). Quantum Computing Since Democritus. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511979309. ISBN 978-0-521-19956-8. OCLC 829706638.

- Akama, Seiki (2014). Elements of Quantum Computing: History, Theories and Engineering Applications. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08284-4. ISBN 978-3-319-08284-4. OCLC 884786739.

- Benenti, Giuliano; Casati, Giulio; Rossini, Davide; Strini, Giuliano (2019). Principles of Quantum Computation and Information: A Comprehensive Textbook (2nd ed.). doi:10.1142/10909. ISBN 978-981-3237-23-0. OCLC 1084428655.

- Bernhardt, Chris (2019). Quantum Computing for Everyone. ISBN 978-0-262-35091-4. OCLC 1082867954.

- Hidary, Jack D. (2021). Quantum Computing: An Applied Approach (2nd ed.). doi:10.1007/978-3-030-83274-2. ISBN 978-3-03-083274-2. OCLC 1272953643.

- Quantum Computation and Information: From Theory to Experiment. Topics in Applied Physics. 102. 2006. doi:10.1007/3-540-33133-6. ISBN 978-3-540-33133-9.