Atonement in Judaism

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

Atonement in Judaism is the process of causing a sin to be forgiven or pardoned. Judaism describes various means of receiving atonement for sin, that is, reconciliation with God and release from punishment. The main method of atonement is via repentance. Other means (e.g. Temple sacrifices, judicial punishments, and returning stolen property) may be involved in the atonement process, together with repentance.

In Rabbinic Judaism

In Rabbinic Judaism, atonement is achieved through repentance, which can be followed by some combination of the following:

- confession

- restitution

- the occurrence of Yom Kippur (the day itself, as distinct from the Temple service performed on it)

- tribulations (unpleasant life experiences)

- the experience of dying.

- the carrying out of a sentence of lashes or execution imposed by an ordained court (not now in existence)

- Temple service (not now in existence, e.g. bringing a sacrifice).

Which of these additions are required varies according to the severity of the sin, whether it was done willfully, in error, or under duress, whether it was against God alone or also against a fellow person, and whether the Temple service and ordained law courts are in existence or not. Repentance is needed in all cases of willful sin, and restitution is always required in the case of sin against a fellow person, unless the wronged party waives it.

According to Maimonides, the requirements for atonement of various sins between man and God are as follows:[1]

| Sinned under duress | Sinned in error | Sinned willfully | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive commandment | none | none | Repentance + confession or Yom Kippur Temple service |

| Negative commandment | none | none | Repentance + confession + Yom Kippur or Yom Kippur Temple service |

| Severe negative commandment | none | Sin offering (if Temple exists) in some cases + confession | Repentance + confession + Yom Kippur + tribulations or Repentance + confession + Yom Kippur Temple service |

| Profaning God's name | Repentance | Sin offering (if Temple exists) in some cases + confession | Repentance + confession + Yom Kippur + tribulations + dying |

The sentence of an ordained court (when available) can also substitute for Yom Kippur + tribulations + dying.

Anyone guilty of a sin which is punished by Kareth ("excision") may be atoned by receiving lashes. According to the Mishnah: "If by the commission of a single sin one forfeits his soul before God, then all the more so by a single meritorious deed (such as voluntary submission to punishment) his soul should be saved."[2]

In Judaism, once a person has repented, they can be close to and beloved of God, even if their atonement is not yet complete.[3]

Repentance

Repentance from sin (Hebrew: teshuvah, literally "return (to God)") has the power to wipe out one's sins, eliminating the punishment for sin and obtaining God's forgiveness.[4] When one repents with the correct intentions, one's sins are said to actually be transformed into merits.[5]

Judaism describes various means of receiving atonement for sin (e.g. Temple sacrifices, judicial punishments, and returning stolen property). However, in general these methods only achieve atonement if one has also repented for the sin:

Those who must bring sin-offerings or guilt offerings... their sacrifices do not atone for them until they repent... And similarly, one who was obligated the death penalty or lashes, their death or lashes does not atone for them, unless they repent and confess. And similarly, one who injures his fellow or damages his property, even if he paid to him what was obligated, does not receive atonement until he confesses and repents from ever doing such actions again... The scapegoat [of Yom Kippur] atones for all sins in the Torah... on condition that one has repented. But if he did not repent, the scapegoat only atones for minor sins... When the Temple is not in existence, and we have no altar for atonement, there exists [for atonement] nothing other than repentance. Repentance atones for all sins... and the essence of Yom Kippur atones for those who repent.[6]

Judaism teaches that our personal relationship with God allows us to return to God at any time as Malachi 3:7 says, "Return to Me and I shall return to you," and Ezekiel 18:27, "When the wicked man turns away from his wickedness that he has committed, and does that which is lawful and right, he shall save his soul alive." Additionally, God is compassionate and forgiving as is indicated in Daniel 9:18, "We do not present our supplications before You because of our righteousness, but because of Your abundant mercy." The poem Unetanneh Tokef summarizes the Jewish attitude as follows:

For You [God] do not desire a person's death, but rather that he repent from his way, and live. Until the day of his death You wait for him; if he repents, You accept him immediately.[7]

Animal sacrifice and other means of atonement

A number of animal sacrifices were prescribed in the Torah (five books of Moses) as part of the atonement process. The sin-offering and guilt offering were offered for individual sins,[8] while the Yom Kippur Temple service helped achieve atonement at a national level.[9]

However, the role of sacrifices in atonement was strictly limited, and simply bringing an offering never automatically caused God to forgive a sin. Standard sin-offerings could only be offered for unintentional sins;[10] according to the rabbis, they could not be offered for all sins, but only for unintentional violations of some of the most serious sins.[11] In addition, sacrifices generally had no expiating effect without sincere repentance[12] and restitution to any person who was harmed by the violation.[13] The Hebrew Bible tells of people who returned to God through repentance and prayer alone, without sacrifices: for example, both Jews and non-Jews in the books of Jonah and Esther.[14] Additionally, in modern times, Jews do not perform animal sacrifices.

Later Biblical prophets made statements to the effect that the hearts of the people were more important than their sacrifices:

- "Does the LORD delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices as much as in obeying the voice of the LORD? To obey is better than sacrifice, and to heed is better than the fat of rams" (1 Samuel 15:22)

- "To what purpose is the multitude of your sacrifices unto Me? saith the LORD; I am full of the burnt-offerings of rams, and the fat of fed beasts; and I delight not in the blood of bullocks, or of lambs, or of he-goats" (Isaiah 1:11)

- "For I [God] desire mercy, and not sacrifice, and the knowledge of God rather than burnt-offerings" (Hosea 6:6)

- "Take with you words and return to the LORD; say to him, 'Take away all iniquity; accept what is good; instead of bulls we offer our lips.'" (Hosea 14:3)

- "For you will not delight in sacrifice, or I would give it; you will not be pleased with a burnt offering. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart" (Psalm 51:18-9)

- "In sacrifice and offering, you have not delighted, but you have given me an open ear. Burnt offering and sin offering you have not required." (Psalm 40:7)

Similarly, in many places Rabbinic literature emphasizes that performing charitable deeds, praying, and studying Torah are more meritorious than animal sacrifice, and can replace animal sacrifice when the Temple is not active:

- "Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai was walking with ... Rabbi Yehoshua, ...Rabbi Yehoshua looked at the Temple ruins and said, ' ... The place that atoned for the sins of the people Israel lies in ruins!' Then Rabbi Yohannan ben Zakkai spoke to him these words of comfort: '... We can still gain ritual atonement through deeds of loving-kindness.'"[15]

- "Rabbi Elazar said: Doing righteous deeds of charity is greater than offering all of the sacrifices, as it is written: 'Doing charity and justice is more desirable to the Lord than sacrifice' (Proverbs 21:3)."[16]

- "Rabbi Shmuel bar Nahmani said: The Holy One Said to David: 'Solomon, your son is building the Temple. Is this not for the purpose of offering sacrifices there? The justice and righteousness of your actions are more precious to me than sacrifices.' And how do we know this? 'To do what is right and just is more desirable to the Lord than sacrifice.' (Proverbs 21:3)"[17]

- "One who does teshuvah is considered as if he went to Jerusalem, rebuilt the Temple, erected the altar, and offered all the sacrifices ordained by the Torah. [For the Psalm says], 'The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, You will not despise [51:19]'" [18]

- "Rava said: Whoever studies Torah does not need [to sacrifice offerings]."[19]

- "Said God: In this world, a sacrifice effected their atonement, but in the World to Come, I will forgive your sins without a sacrifice."[20]

- "Even if a man has sinned his whole life, and repents on the day of his death, all his sins are forgiven him"[21]

- "As long as the Temple stood, the altar atoned for Israel, but now, one's table atones [when the poor are invited as guests]."[22]

- The poem Unetanneh Tokef (recited on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur) states that prayer, repentance and tzedakah (giving charity) atone for sin.

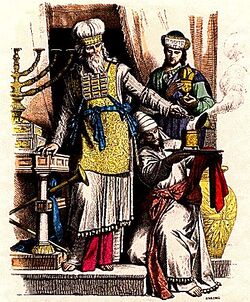

Jewish High Priest and Atonement

- According to the Talmud, the wearing of the Priestly golden head plate atoned for the sin of arrogance on the part of the Children of Israel (B.Zevachim 88b) and she also symbolizes that the high priest bears the lack of all the offerings and gifts of the sons of Israel. And it must be constantly on his head for the good pleasure of God towards them (Exodus 28:38).

- According to the Talmud, the wearing of the Priestly turban atoned for the sin of haughtiness on the part of the Children of Israel (B. Zevachim 88b).

- According to the Talmud, the wearing of the Priestly ephod atoned for the sin of idolatry on the part of the Israelites.[23]

- According to the Talmud, the wearing of the Priestly sash atoned for "sins of the heart" (impure thoughts) on the part of the Children of Israel.[24]

- According to the Talmud, the wearing of the Priestly tunic and the rest of the priestly garments atoned for the sin of bloodshed on the part of the Children of Israel (B.Zevachim 88b).

- According to the Talmud, the Priestly undergarments atone for the sin of sexual transgressions on the part of the Children of Israel (B.Zevachim 88b).

In other Jewish denominations

Some Jewish denominations may differ with Rabbinic Judaism on the importance or mechanics of atonement. Consult the articles on specific denominations for details.

References

- ↑ Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Teshuva 1:1–4.

- ↑ Mishnah, Makkot 3:15

- ↑ Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Teshuva 7:7.

- ↑ See Ezekiel 33:11, 33:19, Jeremiah 36:3, etc.

- ↑ Yoma 86b

- ↑ Mishneh Torah, Laws of Repentance 1:3-8

- ↑ Unetaneh_Tokef

- ↑ Leviticus 4-5

- ↑ Leviticus 16

- ↑ Leviticus 4:2

- ↑ Mishnah, Kritot 1:1-2

- ↑ Mishneh Torah, Laws of Repentance 1:3,6

- ↑ Mishnah, Yoma 8:9

- ↑ "The Jewish Response to Missionaries (8-Page Booklet) English". https://jewsforjudaism.org/knowledge/documents/the-jewish-response-to-missionaries-8-page-booklet.

- ↑ Avot of Rabbi Natan 4:5

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud, Sukkah 49

- ↑ Talmud Yerushalmi, Berakhot 2:1

- ↑ Leviticus Rabbah 7:2

- ↑ Menahot 110a

- ↑ Tanhuma Shemini, paragraph 10

- ↑ Mishneh Torah, Teshuvah 2:1

- ↑ Berachot 55a

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud, Zevachim 88:B

- ↑ Zevachim 88b

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore, ed (1901–1906). "CAPITAL PUNISHMENT". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/4005-capital-punishment.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore, ed (1901–1906). "CAPITAL PUNISHMENT". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/4005-capital-punishment.

|

KSF

KSF