Foreign relations of the Holy See

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 38 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 38 min

Template:Politics of the Holy SeeThe Holy See has long been recognised as a subject of international law and as an active participant in international relations. It is distinct from the city-state of the Vatican City, over which the Holy See has "full ownership, exclusive dominion, and sovereign authority and jurisdiction".[1]

The diplomatic activities of the Holy See are directed by the Secretariat of State (headed by the Cardinal Secretary of State), through the Section for Relations with States.

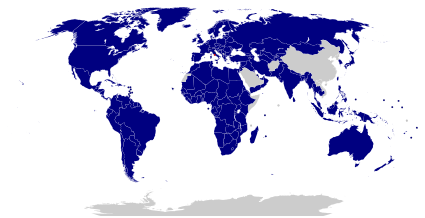

While not being a member of the United Nations in its own right, the Holy See recognizes all UN member states (Except Afghanistan, Brunei, Laos, North Korea, The People's Republic of China, Saudi Arabia, Somalia and Vietnam). In addition, the Holy See recognizes the State of Palestine and the Republic of China (Taiwan).[2][3]

The term "Vatican Diplomatic Corps", by contrast with the diplomatic service of the Holy See, properly refers to all those diplomats accredited to the Holy See, not those who represent its interests to other nations and international bodies. Since 1961, Vatican diplomats also enjoy diplomatic immunity.[4]

History

Since medieval times the episcopal see of Rome has been recognized as a sovereign entity. Earlier, there were papal representatives (apocrisiarii) to the Emperors of Constantinople, beginning in 453, but they were not thought of as ambassadors.[5]: 64 In the eleventh century the sending of papal representatives to princes, on a temporary or permanent mission, became frequent.[5]: 65 In the fifteenth century it became customary for states to accredit permanent resident ambassadors to the Pope in Rome.[5]: 68 The first permanent papal nunciature was established in 1500 in Venice. Their number grew in the course of the sixteenth century to thirteen, while internuncios (representatives of second rank) were sent to less-powerful states.[5]: 70 After enjoying a brilliant period in the first half of the seventeenth century, papal diplomacy declined after the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, being assailed especially by royalists and Gallicans, and the number of functioning nuncios was reduced to two in the time of Napoleon, although in the same period, in 1805, Prussia became the first Protestant state to send an ambassador to Rome. There was a revival after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, which, while laying down that, in general, the order of precedence between ambassadors would be determined by the date of their arrival, allowed special precedence to be given to the nuncio, by which he would always be the dean of the diplomatic corps.[6]

In spite of the extinction of the Papal States in 1870, and the consequent loss of territorial sovereignty, and in spite of some uncertainty among jurists as to whether it could continue to act as an independent personality in international matters, the Holy See continued in fact to exercise the right to send and receive diplomatic representatives, maintaining relations with states that included the major powers of Russia, Prussia, and Austria-Hungary.[7] Countries continued to receive nuncios as diplomatic representatives of full rank, and where, in accordance with the decision of the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the Nuncio was not only a member of the Diplomatic Corps but its dean, this arrangement continued to be accepted by the other ambassadors.[7]

With the First World War and its aftermath the number of states with diplomatic relations with the Holy See increased. For the first time since relations were broken between the Pope and Queen Elizabeth I of England, a British diplomatic mission to the Holy See was opened in 1914.[8] The result was that, instead of diminishing, the number of diplomats accredited to the Holy See grew from sixteen in 1870 to twenty-seven in 1929, even before it again acquired territorial sovereignty with the founding of the State of Vatican City.[9]

In the same period, the Holy See concluded a total of twenty-nine concordats and other agreements with states, including Austro-Hungary in 1881, Russia in 1882 and 1907, France in 1886 and 1923.[9] Two of these concordats were registered at the League of Nations at the request of the countries involved.[10]

While bereft of territorial sovereignty, the Holy See also accepted requests to act as arbitrator between countries, including a dispute between Germany and Spain over the Caroline Islands.[9]

The Lateran Treaty of 1929 and the founding of the Vatican City State was not followed by any great immediate increase in the number of states with which the Holy See had official relations. This came later, especially after the Second World War.

Since World War II, the Holy See's foreign relations are generally associated with the concept of soft power and generally seek to promote peace and humanitarian programs.[11]: 181 The Holy See's foreign relations are less focused on traditional state interests like state security and the like.[11]: 181

The Vienna Convention of 18 April 1961 also established diplomatic immunity for the Vatican's foreign diplomats.[4] Such immunity can only be revoked by the Holy See.[4]

After the Cuban missile crisis demonstrated the risk of nuclear war, The Holy See became convinced that it had been too reluctant to engage with the communist countries.[12]: 17 Through its foreign relations approach of Ostpolitik, the Vatican downplayed the role of ideological conflicts in international relations and reduced its anti-communist rhetoric.[12]: 17 The Vatican also sought to use this approach to make the sacraments and church public life more available in the communist countries.[12]: 17

Diplomatic relations

List of 183 countries which the Holy See maintains diplomatic relations with:

| ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Country | Date[13] |

| 1 | 12 February 1481[14] | |

| 2 | March 1559[15] | |

| 3 | ||

| 4 | 1600s | |

| 5 | May 1829[16] | |

| 6 | 17 July 1829[17] | |

| 7 | 17 July 1834[18] | |

| 8 | 26 November 1835 | |

| 9 | 21 June 1875[19] | |

| 10 | 6 August 1877[20] | |

| 11 | 6 August 1877[21] | |

| 12 | 10 October 1877[22] | |

| 13 | 15 December 1877[23] | |

| 14 | Template:DTS[24] | |

| 15 | Template:DTS[24] | |

| 16 | Template:DTS[24] | |

| 17 | 1881 | |

| 18 | 1881 | |

| 19 | January 1891[25] | |

| 20 | 19 August 1908[26] | |

| 21 | 19 December 1908[27] | |

| — | 19 December 1908[27][28] | |

| 22 | 16 June 1919[29] | |

| 23 | 22 March 1920[30] | |

| 24 | 10 August 1920[31][32] | |

| 25 | 12 October 1922[33] | |

| 26 | 21 September 1923[34] | |

| 27 | April 1926 | |

| 28 | 10 May 1927[35] | |

| 29 | 15 December 1927 | |

| 30 | 24 June 1929 | |

| 31 | 27 November 1929 | |

| — | Template:Country data Sovereign Military Order of Malta | February 1930 |

| 32 | 2 September 1935 | |

| 33 | 16 March 1936 | |

| 34 | 4 May 1942[36] | |

| 35 | 1942[37] | |

| — | ||

| 36 | 9 August 1946 | |

| 37 | November 1946 | |

| 38 | 23 August 1947 | |

| 39 | 12 June 1948 | |

| 40 | 13 March 1950 | |

| 41 | 8 April 1951 | |

| 42 | 6 October 1951 | |

| 43 | 21 February 1953 | |

| 44 | 2 May 1953 | |

| 45 | 1 June 1954 | |

| 46 | 16 June 1954[38] | |

| 47 | 20 March 1957 | |

| 48 | 25 January 1960 | |

| 49 | 17 November 1961 | |

| 50 | 11 February 1963 | |

| 51 | 16 February 1963 | |

| 52 | 11 December 1963 | |

| 53 | 6 June 1964 | |

| 54 | 15 May 1965 | |

| 55 | 19 June 1965 | |

| 56 | 15 December 1965 | |

| 57 | 5 February 1966 | |

| 58 | 26 August 1966 | |

| 59 | 27 August 1966 | |

| 60 | 1 September 1966 | |

| 61 | 24 December 1966 | |

| 62 | 11 March 1967 | |

| 63 | 13 May 1967 | |

| 64 | 31 October 1967 | |

| 65 | 19 April 1968 | |

| 66 | 28 April 1968 | |

| 67 | 21 October 1968 | |

| 68 | 16 October 1969 | |

| 69 | 9 March 1970 | |

| 70 | 14 August 1970 | |

| 71 | 26 October 1970 | |

| 72 | 29 June 1971 | |

| 73 | 20 July 1971 | |

| 74 | 6 March 1972 | |

| 75 | 22 March 1972 | |

| 76 | 29 April 1972 | |

| 77 | 25 September 1972 | |

| 78 | 31 January 1973 | |

| 79 | 24 March 1973 | |

| 80 | 14 June 1973 | |

| 81 | 20 June 1973 | |

| 82 | 6 September 1975 | |

| 83 | 20 November 1975 | |

| 84 | 20 November 1975 | |

| 85 | 15 January 1976 | |

| 86 | 12 May 1976 | |

| 87 | 12 October 1976[39] | |

| 88 | 31 January 1977 | |

| 89 | 7 March 1977 | |

| 90 | 7 June 1978 | |

| 91 | 23 July 1978 | |

| 92 | 12 September 1978 | |

| 93 | 17 February 1979 | |

| 94 | 19 April 1979 | |

| 95 | 17 July 1979 | |

| 96 | 20 July 1979 | |

| 97 | 27 July 1979 | |

| 98 | 29 October 1979 | |

| 99 | 26 June 1980 | |

| 100 | 21 April 1981 | |

| 101 | 24 June 1981 | |

| 102 | 1 September 1981 | |

| 103 | 24 December 1981 | |

| 104 | 16 January 1982 | |

| 105 | 2 August 1982 | |

| 106 | 2 August 1982 | |

| 107 | 2 August 1982 | |

| 108 | 9 March 1983 | |

| 109 | 10 September 1983 | |

| 110 | 10 January 1984 | |

| 111 | 9 May 1984 | |

| 112 | 27 July 1984 | |

| 113 | 1 September 1984 | |

| 114 | 21 December 1984 | |

| 115 | 28 August 1985 | |

| 116 | 21 June 1986 | |

| 117 | 12 July 1986 | |

| 118 | 15 December 1986 | |

| 119 | 28 November 1988 | |

| 120 | 16 April 1990 | |

| 121 | 6 December 1990 | |

| 122 | 7 September 1991 | |

| 123 | 30 September 1991 | |

| 124 | 1 October 1991 | |

| 125 | 3 October 1991 | |

| 126 | 8 February 1992 | |

| 127 | 8 February 1992 | |

| 128 | 8 February 1992 | |

| 129 | 11 March 1992 | |

| 130 | 4 April 1992 | |

| 131 | 23 May 1992 | |

| 132 | 23 May 1992 | |

| 133 | 23 May 1992 | |

| 134 | 23 May 1992 | |

| 135 | 1 June 1992 | |

| 136 | 18 August 1992 | |

| 137 | 27 August 1992 | |

| 138 | 21 September 1992 | |

| 139 | 17 October 1992 | |

| 140 | 17 October 1992 | |

| 141 | 11 November 1992 | |

| 142 | 1 January 1993 | |

| 143 | 30 December 1993 | |

| 144 | 16 January 1994 | |

| 145 | 26 January 1994 | |

| 146 | 3 March 1994 | |

| 147 | 5 March 1994 | |

| 148 | 25 March 1994 | |

| 149 | 10 June 1994 | |

| 150 | 15 June 1994 | |

| 151 | 20 July 1994 | |

| 152 | 24 August 1994 | |

| 153 | 21 December 1994 | |

| 154 | 10 April 1995 | |

| 155 | 16 June 1995 | |

| 156 | 15 July 1995 | |

| 157 | 12 September 1995 | |

| 158 | 14 December 1995 | |

| 159 | 10 June 1996 | |

| 160 | 15 June 1996 | |

| 161 | 30 July 1996 | |

| 162 | 10 March 1997 | |

| 163 | 9 June 1997 | |

| 164 | 8 July 1997 | |

| 165 | 13 October 1998 | |

| 166 | 17 December 1998 | |

| — | 29 April 1999 | |

| 167 | 19 July 1999 | |

| 168 | 12 January 2000 | |

| 169 | 20 May 2000 | |

| 170 | 20 May 2002 | |

| 171 | 18 November 2002 | |

| 172 | 16 December 2006 | |

| 173 | 30 May 2007[40] | |

| 174 | 4 November 2008 | |

| 175 | 9 December 2009 | |

| 176 | 27 July 2011 | |

| 177 | 22 February 2013 | |

| — | 13 May 2015[41] | |

| 178 | 9 December 2016[42] | |

| 179 | 4 May 2017 | |

| 180 | 23 February 2023[40] | |

Bilateral relations

The Holy See, as a non-state sovereign entity and full subject of international law, started establishing diplomatic relations with sovereign states in the 15th century.[43] It had the territory of the States of the Church under its direct sovereign rule since centuries before that time. Currently it has the territory of the State of the Vatican City under its direct sovereign rule. In the period of 1870–1929 between the annexation of Rome by the Kingdom of Italy and the ratification of the Lateran Treaty establishing the current Vatican City State, the Holy See was devoid of territory. In this period some states suspended their diplomatic relations, but others retained them (or established such relations for the first time or reestablished them after a break), so that the number of states that did have diplomatic relations with the Holy See almost doubled (from 16 to 27) in the period between 1870 and 1929.[9]

The Holy See currently has diplomatic relations with 184 sovereign states.[44] These include 181 United Nations member states, the UN observer State of Palestine,[43] the partially internationally recognized Republic of China (Taiwan), and the Cook Islands (a non-UN state in free association with New Zealand).[45] In addition, it maintains relations with the sovereign entity Order of Malta and the supranational union European Union.[46] The Holy See presently lacks diplomatic relations with 12 UN member states.[47]

By agreement with the government of Vietnam, it has a non-resident papal representative to that country.[48] It has official formal contacts, without establishing diplomatic relations, with: Afghanistan, Brunei, Somalia and Saudi Arabia.[49]

The Holy See additionally maintains some apostolic delegates to local Catholic Church communities which are not accredited to the governments of the respective states and work only in an unofficial, non-diplomatic capacity.[50] The regions and states where such non-diplomatic delegates operate are: Brunei, Comoros, Laos, Maldives, Somalia, Vietnam, Jerusalem and the Palestinian territories (Palestine), Pacific Ocean (Tuvalu, dependent territories[51]), Arabian Peninsula (foreigners in Saudi Arabia), Antilles (dependent territories[52]), apostolic delegate to Kosovo[53] (Republic of Kosovo) and the apostolic prefecture of Western Sahara (Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic).

The Holy See has no relations of any kind with the following states:

- Kingdom of Bhutan (see Catholic Church in Bhutan)

- Republic of the Maldives (see Catholic Church in the Maldives)

- People's Republic of China (see Catholic Church in China)

- Democratic People's Republic of Korea (see Catholic Church in North Korea)

91 embassies to the Holy See are based in Rome.[44]

The Holy See is the only European subject of international law to have diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (Taiwan), although there have been reports of informal talks between the Holy See and the government of the People's Republic of China on establishing diplomatic relations,[54] restoring the situation that existed when the papal representative, Antonio Riberi, was part of the diplomatic corps that accepted the Communist government military victory instead of withdrawing with the Nationalist authorities to Taiwan.[11]: 183 He was later expelled,[11]: 184 after which the Holy See sent its representative to Taipei instead.[11]: 187

During the pontificate of Pope Benedict XVI relations were established with Montenegro (2006), the United Arab Emirates (2007), Botswana (2008), Russia (2009), Malaysia (2011), and South Sudan (2013),[55] and during the pontificate of Pope Francis, diplomatic relations were established with the State of Palestine (2015),[56] Mauritania (2016),[57] Myanmar (2017),[58] and Oman (2023).[59] "Relations of a special nature" had previously been in place with Russia.[60]

Africa

| Country | Formal relations begun or resumed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | See Algeria–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1967 | See Central African Republic–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1977 | See Democratic Republic of the Congo–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1947 | See Apostolic Nunciature to Egypt.

Pope Francis met Grand Imam of al-Azhar Ahmad al-Tayyeb in several occasions to improve relations among different faiths.[65] | |

| 1970 | See Holy See-Ivory Coast relations. | |

| 1959 |

| |

| 1960 |

| |

| 1963 | See Republic of the Congo–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1964 |

| |

| 1969 |

| |

| 1977 |

|

Americas

| Country | Formal relations begun or resumed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | See Argentina–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1983 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations on 9 March 1983.[73] | |

| 1877 | Bolivian President Evo Morales met with Pope Francis in 2015,[74] and 2016.[75] | |

| 1829 | See Brazil–Holy See relations

| |

| 1969 | See Canada–Holy See relations.

Although the Roman Catholic Church has been territorially established in what later became the independent state of Canada since the founding of New France in the early 17th century, Holy See–Canada relations were only officially established under the papacy of Paul VI in 1969. | |

| 1877 |

| |

| 1835 |

| |

| 1935 | See Cuba–Holy See relations

| |

| 1881 | See Apostolic Nunciature to the Dominican Republic. | |

| 1877 | See Apostolic Nunciature to Ecuador. | |

| 1881 | See Apostolic Nunciature to Haiti. | |

| 1992 | See Holy See–Mexico relations.

| |

| 1862 | See Holy See–Nicaragua relations. | |

| 1877 | See Apostolic Nunciature to Paraguay. | |

| 1877 | See Holy See–Peru relations

| |

| 1984 | See Holy See–United States relations.

| |

| 1877 | See Holy See–Uruguay relations

| |

| 1869 | See Holy See–Venezuela relations.

Diplomatic relations were established in 1869. The Holy See has a nunciature in Caracas. Venezuela has an embassy in Rome. |

Asia

| Country | Formal relations begun or resumed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1992 | ||

| 1992 | ||

| 1972 | See Bangladesh–Holy See relations. | |

| Template:Country data China, Republic of | 1942 | See Holy See–Taiwan relations.

|

| 1948 | See Holy See–India relations.

| |

| 1947 | See Holy See–Indonesia relations. | |

| 1954 | See Holy See–Iran relations.

The two countries have had formal diplomatic relations since 1954, since the pontificate of Pius XII, and have been maintained during Islamic revolution.[84] In 2008 relations between Iran and the Holy See were "warming", and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad "said the Vatican was a positive force for justice and peace" when he met with the Papal nuncio to Iran, Archbishop Jean-Paul Gobel.[85] | |

| 1993 | See Holy See–Israel relations.

Holy See–Israel relations have officially existed since 1993 with the adoption of the fundamental agreement between the two parties. However, relations remain tense because of the non-fulfillment of the accords giving property rights and tax exemptions to the Church. | |

| 1994 | See Holy See–Jordan relations.

| |

| Kazakhstan | 1992 | See Holy See–Kazakhstan relations. |

| See Holy See–Kurdistan Region relations. | ||

| 1969 |

| |

| 1947 | See Holy See–Lebanon relations.

| |

| 2011 | See Holy See–Malaysia relations.

| |

| 2017 | See Holy See–Myanmar relations.

| |

| 1983 | See Holy See–Nepal relations. | |

| Oman | 2023 | See Holy See–Oman relations. |

| Pakistan | 1961 | See Holy See–Pakistan relations.

|

| 1994 | See Holy See–Palestine relations.

The Holy See and the State of Palestine established formal diplomatic relations in 2015, through the mutual signing of the Comprehensive Agreement between the Holy See and the State of Palestine.[56] An Apostolic Delegation (a non-diplomatic mission of the Holy See) denominated "Jerusalem and Palestine" had existed since 11 February 1948, and the Palestine Liberation Organization had established official (non diplomatic) relations with the Holy See in October 1994, with the opening of an office in Rome. The Holy See, along with many other states, supports a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine. | |

| 1951 | See Holy See–Philippines relations. | |

| 2002[94] |

| |

| See Holy See–Saudi Arabia relations.

No official diplomatic relationship exists. There have been some important high-level meetings between Saudi and Vatican officials in order to discuss issues and organize dialogue between religions. | ||

| 1966[95] | See Holy See–South Korea relations.

| |

| 1978 | See Holy See–Sri Lanka relations.

The Holy See has a nunciature in Colombo. Sri Lanka has an ambassador accredited to the Holy See. | |

| 1946 | See Holy See–Syria relations

| |

| 1957 |

History

| |

| 1868 | See Holy See–Turkey relations.

| |

| 2007[109] | See Holy See–United Arab Emirates relations.

| |

| See Holy See–Vietnam relations.

Diplomatic relations have not been established with Vietnam. An Apostolic Delegation (a papal mission accredited to the Catholic Church in the country but not officially to the Government) still exists on paper and as such is listed in the Annuario Pontificio; but since the end of the Vietnam War admittance of representatives to staff it has not been permitted. Temporary missions to discuss with the Government matters of common interest are sent every year or two. | ||

| 1998 | See Foreign relations of Yemen.

The Holy See and Yemen established diplomatic relations on 13 October 1998.[111] Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh met Pope John Paul II in November 2004.[112] |

Europe

| Country | Formal relations begun or resumed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 |

| |

| 1835 | See Apostolic Nunciature to Belgium. | |

| 1992 | See Bosnia and Herzegovina–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1992 | See Croatia–Holy See relations.

| |

| See Apostolic Nunciature to Cyprus. | ||

| 1982 | ||

| 1970 | See Holy See–European Union relations.

Many of the founders of the European Union were inspired by Catholic ideals, notably Robert Schuman, Alcide de Gasperi, Konrad Adenauer, and Jean Monnet.[117][118] | |

| 1942[119][120] |

Finland has a resident embassy to the Holy See in Rome,[121] located at the Finnish Institute in Rome in Villa Lante al Gianicolo. | |

| No later than 987, based upon already-established relations no later than 714 |

See France–Holy See relations.

Relations between France and the Catholic Church are very ancient and have existed since the fifth century AD, and have been durable to the extent that France is sometimes called the eldest daughter of the Church. Areas of cooperation between Paris and the Holy See have traditionally included education, health care, the struggle against poverty and international diplomacy. Before the establishment of the welfare state, Church involvement was evident in many sectors of French society. Today, Paris's international peace initiatives are often in line with those of the Holy See, who favors dialogue on a global level. | |

| 1951 | See Germany–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1980 | See Greece–Holy See relations.

| |

| 1977 |

Diplomatic relations were established in 1977, but the Pope Paul VI in his greeting to the first Ambassador from Iceland referred to these relations as "the millenary ties between your people (i.e. of Iceland) and the Catholic Church".[123] | |

| 1929 | See Holy See–Ireland relations.

The majority of Irish people are Roman Catholic. The Holy See has a nunciature in Dublin. Ireland had, in Rome, an embassy to the Holy See. The government closed that embassy in 2011 for financial reasons; however, it re-opened the embassy in 2014.[124] Currently Ireland's representative to the Holy See is a 'non-resident ambassador',[124] who is an ordinary resident of Dublin. | |

| 1929 | See Holy See–Italy relations.

Because of the small size of the Vatican City State, embassies accredited to the Holy See are based on Italian territory. Treaties signed between Italy and the Vatican City State permit such embassages. Like the Embassy of Italy, the Embassy of Andorra to the Holy See is also based on its home territory. | |

| 1991 |

| |

| 1891 | See Apostolic Nunciature to Luxembourg. | |

| 1127 1530; 1798; 1800; 1813 1965 |

| |

| 1875 | See Apostolic Nunciature to Monaco. | |

| 1829 | See Apostolic Nunciature to the Netherlands.

| |

| 1982 | See Holy See–Norway relations. | |

| 1555 | See Holy See–Poland relations. | |

| 1179 1670 1918 |

Portugal has one of the oldest relations with the Holy See; it received formal recognition as independent from Castile in 1179 and has always kept a strong relation with the Holy See following the maritime expansion and the Christianization of overseas territories. Relations suspended from 1640 to 1670, following the war against Spain (the Holy See did not recognise the Portuguese independence before the end of the war in 1668) and from 1911 to 1918 (following the proclamation of the Portuguese Republic in October 1910 and the approvation of the Law of Separation of the Church and the State). Concordats signed in 1940 and 2004.

| |

| 1920;1990 | See Holy See–Romania relations.

| |

| 2009 | See Holy See–Russia relations.

| |

| 2003 | See Holy See–Serbia relations.

| |

| 1530 | See Holy See–Spain relations.

| |

| 1586 | See Holy See–Switzerland relations.

| |

| 1992 | ||

| 1982 | See Holy See–United Kingdom relations

The UK established diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom on 16 January 1982.

Both countries share common membership of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. |

Oceania

| Country | Formal relations begun or resumed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1973 |

| |

| 1948 |

| |

| 1973 | See Holy See-Papua New Guinea relations.

|

Multilateral politics

Participation in international organizations

The Holy See is active in international organizations and is a member of the following groups:[144]

- International Committee of Military Medicine (ICMM)

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

- International Organization for Migration (IOM)[145]

- International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI)

- Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

- Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)

- Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO)

- International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT)

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

The Holy See has the status of permanent observer state in:

- United Nations (UN)

- World Health Organization (WHO)[146]

The Holy See is also a permanent observer of the following international organizations:

- Council of Europe in Strasbourg

- International Labour Organization (ILO)

- International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD)

- International Commission on Civil Status (CIEC)

- Latin Union (LU)

- Organization of American States (OAS)

- Organisation of African Unity (OAU)

- United Nations

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization)

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO)

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

- United Nations International Drug Control Programme (UNDCP)

- United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (UNCHS)

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

- World Tourism Organization (WToO)

- World Trade Organization (WTO)

- World Food Programme (WFP)

The Holy See is an observer on an informal basis of the following groups:

- Asian-African Legal Consultative Organization (AALCO)

- International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (ISDR, 1990s)

- International Maritime Organization (IMO)

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

- United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS)

- World Meteorological Organization in Geneva (WMO)

The Holy See sends a delegate to the Arab League in Cairo. It is also a guest of honour to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

Activities of the Holy See within the United Nations system

Since 6 April 1964, the Holy See has been a permanent observer state at the United Nations. In that capacity, the Holy See has since had a standing invitation to attend all the sessions of the United Nations General Assembly, the United Nations Security Council, and the United Nations Economic and Social Council to observe their work, and to maintain a permanent observer mission at the UN headquarters in New York.[147] Accordingly, the Holy See has established a Permanent Observer Mission in New York, has sent representatives to all open meetings of the General Assembly and of its Main Committees, and has been able to influence their decisions and recommendations.

Relationship with Vatican City

Although the Holy See is closely associated with Vatican City, the independent territory over which the Holy See is sovereign, the two entities are separate and distinct.

The State of the Vatican City was created by the Lateran Treaty in 1929 to "ensure the absolute and visible independence of the Holy See" and "to guarantee to it an indisputable sovereignty in international affairs" (quotations from the treaty). Archbishop Jean-Louis Tauran, the Holy See's former Secretary for Relations with States, said that the Vatican City is a "minuscule support-state that guarantees the spiritual freedom of the Pope with the minimum territory."[148]

The Holy See, not Vatican City, maintains diplomatic relations with states, and foreign embassies are accredited to the Holy See, not to Vatican City State. It is the Holy See that establishes treaties and concordats with other sovereign entities and likewise, generally, it is the Holy See that participates in international organizations, with the exception of those dealing with technical matters of clearly territorial character,[144] such as:

- European Conference of Postal and Telecommunications Administrations (CEPT)

- European Telecommunication Satellite Organization (EUTELSAT)

- International Grains Council (IGC)

- International Institute of Administrative Sciences (IISA)

- International Telecommunications Satellite Organization (ITSO)

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU)

- Interpol[149]

- Universal Postal Union (UPU)

Under the terms of the Lateran Treaty, the Holy See has extraterritorial authority over various sites in Rome and two Italian sites outside of Rome, including the Pontifical Palace at Castel Gandolfo. The same authority is extended under international law over the Apostolic Nunciature of the Holy See in a foreign country.

Diplomatic representations to the Holy See

Of the diplomatic missions accredited to the Holy See, 91 are situated in Rome, although those countries, if they also have an embassy to Italy, then have two embassies in the same city, since, by agreement between the Holy See and Italy, the same person cannot at the same time be accredited to both. The United Kingdom recently housed its embassy to the Holy See in the same chancery as its embassy to the Italian Republic, a move that led to a diplomatic protest from the Holy See. An ambassador accredited to a country other than Italy can be accredited also to the Holy See. For example, the embassy of India in Bern, accredited to Switzerland and Liechtenstein, is also accredited to the Holy See, while the Holy See maintains an Apostolic Nunciature in New Delhi. For reasons of economy, smaller countries accredit to the Holy See a mission situated elsewhere and accredited also to the country of residence and perhaps other countries.

Rejection of ambassadorial candidates

It has been reported on several occasions that the Holy See will reject ambassadorial candidates whose personal lives are not in accordance with Catholic teachings. In 1973, the Vatican rejected the nomination of Dudley McCarthy as Australia's non-resident ambassador due to his status as a divorcee.[150] According to press accounts in Argentina in January 2008, the country's nominee as ambassador, Alberto Iribarne, a Catholic, was rejected on the grounds that he was living with a woman other than the wife from whom he was divorced.[151] In September 2008, French and Italian press reports likewise claimed that the Holy See had refused the approval of several French ambassadorial candidates, including a divorcee and an openly gay man.[152]

Massimo Franco, author of Parallel Empires, asserted in April 2009 that the Obama administration had put forward three candidates for consideration for the position of United States Ambassador to the Holy See, but each of them had been deemed insufficiently anti-abortion by the Vatican. This claim was denied by the Holy See's spokesman Federico Lombardi, and was dismissed by former ambassador Thomas Patrick Melady as being in conflict with diplomatic practice. Vatican sources said that it is not the practice to vet the personal ideas of those who are proposed as ambassadors to the Holy See, though in the case of candidates who are Catholics and who are living with someone, their marital status is taken into account. Divorced people who are not Catholics can in fact be accepted, provided their marriage situation is in accord with the rules of their own religion.[153]

Treaties and concordats

Since the Holy See is legally capable of ratifying international treaties, and does ratify them, it has negotiated numerous bilateral treaties with states and it has been invited to participate – on equal footing with States – in the negotiation of most universal International law-making treaties. Traditionally, an agreement on religious matters between the Holy See of the Catholic Church and a sovereign state is called a concordat. This often includes both recognition and privileges for the Catholic Church in a particular country, such as exemptions from certain legal matters and processes, issues such as taxation, as well as the right of a state to influence the selection of bishops within its territory.

Bibliography

- Breger, Marshall J. et al. eds. The Vatican and Permanent Neutrality (2022) excerpt

- Cardinale, Hyginus Eugene (1976). The Holy See and the International Order. Colin Smythe, (Gerrards Cross). ISBN 0-900675-60-8.

See also

- Apostolic Nunciature

- Holy See and the United Nations

- Index of Vatican City-related articles

- Legal status of the Holy See

- Catholic Church and politics

- Relations between the Catholic Church and the state

- Catholic Church and ecumenism

Notes

- ↑ The British embassy to the Holy See is a separate embassy to the British embassy to Italy and San Marino.

References

- ↑ Article 3 of the Lateran Treaty, which founded the state

- ↑ "Vatican to sign State of Palestine accord". The Guardian. 13 May 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/13/vatican-to-sign-state-of-palestine-accord.

- ↑ Philip Pullella (26 June 2015). "Vatican signs first treaty with 'State of Palestine', Israel angered". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-vatican-palestinians-idUSKBN0P618120150626.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Holy See waives diplomatic immunity for accused nuncio to France". https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/41727/holy-see-waives-diplomatic-immunity-for-accused-nuncio-to-france.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Hyginus Eugene Cardinale, (1976), The Holy See and the International Order, Colin Smythe, (Gerrards Cross), ISBN 0-900675-60-8.

- ↑ Boczek, Boleslaw Adam (2005). International Law: A Dictionary. p. 47. Scarecrow Press (Lanham, Maryland). ISBN 0-8108-5078-8, ISBN 978-0-8108-5078-1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "30Giorni - Uno strumento docile e fedele al Papa (di Giovanni Lajolo)". http://www.30giorni.it/it/articolo.asp?id=10264.

- ↑ "UK in the Holy See: Previous ambassadors". http://ukinholysee.fco.gov.uk/en/about-us/our-embassy/ambassador/previous-ambassador.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Philippe Levillain, John W. O'Malley, The Papacy: Gaius-Proxies (Routledge, 2002 ISBN 0-415-92230-5, ISBN 978-0-415-92230-2), p. 718

- ↑ J.K.T. Chao, The Evolution of Vatican Diplomacy p. 27

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Moody, Peter (2024). "The Vatican and Taiwan: An Anomalous Diplomatic Relationship". in Zhao, Suisheng. The Taiwan Question in Xi Jinping's Era: Beijing's Evolving Taiwan Policy and Taiwan's Internal and External Dynamics. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781032861661.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Mariani, Paul Philip (2025). China's Church Divided: Bishop Louis Jin and the Post-Mao Catholic Revival. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-29765-4.

- ↑ "Diplomatic relations of the Holy See". https://holyseemission.org/contents/mission/diplomatic-relations-of-the-holy-see.php.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Portugal". https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxpt.html.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Spain". https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxes.html.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Netherlands". http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxnl.html.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Brazil". https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxbr.html.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Belgium". https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxbe.html.

- ↑ "Rapport de Politique Extérieure 2007" (in fr). p. 44. https://www.gouv.mc/Action-Gouvernementale/Monaco-a-l-International/Publications/Rapports-de-Politique-Exterieure. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Bolivia". https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxbo.html.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Ecuador" (in es). https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxec.html.

- ↑ (in es) Memoria que presenta al Congreso nacional .... Peru. Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores. 1879. pp. 337.

- ↑ (in es) Memoria del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores. 1879. pp. 17.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Custer, Carlos Luis (2007). "Derecho de réplica: Argentina/Santa Sede" (in es). Instituto de Relaciones Internacionales 33: 6. https://www.iri.edu.ar/revistas/revista_dvd/revistas/cd%20revista%2033/Nueva%20carpeta/ri%2033%20e%20cust.pdf.

- ↑ "Nunciature to Luxembourg". https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxlu.html.

- ↑ (in es) Colección de leyes, decretos, acuerdos y resoluciones. 1908. pp. 163.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Giuseppe, De Marchi (1957) (in it). Le nunziature apostoliche dal 1800 al 1956. Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. pp. 179.

- ↑ "Nicaragua asks the Holy See to close respective diplomatic missions". 13 March 2023. https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2023-03/nicaragua-asks-the-holy-see-to-close-its-diplomatic-missions.html.

- ↑ "Relacje dyplomatyczne między Polską a Watykanem" (in pl). 14 December 2018. https://www.ekai.pl/relacje-dyplomatyczne-miedzy-polska-a-watykanem/.

- ↑ Klimek, Antonín; Kubů, Eduard (1995) (in cs). Československá zahraniční politika 1918-1938 : kapitoly z dějin mezinárodních vztahů. Institut pro středoevropskou kulturu a politiku. pp. 99.

- ↑ Jedin, Hubert; Dolan, John Patrick (1980). History of the Church. 10. Seabury Press. pp. 521.

- ↑ Rapports: Chronologie. Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România. 1980. pp. 537.

- ↑ (in la) Acta Apostolicae Sedis. XIV. 1922. pp. 563. https://www.vatican.va/archive/aas/documents/AAS-14-1922-ocr.pdf. Retrieved 14 July 2020. "Internunzio Apostolico nell'America Centrale"

- ↑ "RELACIONES DIPLOMÁTICAS DE LA REPÚBLICA DE PANAMÁ". p. 195. http://www.mire.gob.pa/sites/default/files/documentos/Trasnsparencia/gestion-anual-2011-2012.pdf.

- ↑ "Diplomatic Relations of Romania". https://www.mae.ro/en/node/2187.

- ↑ "Japan's PM tells Vatican of concern about human rights in Hong Kong and Xinjiang". Vatican News. 4 May 2022. https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2022/05/04/japans-pm-tells-vatican-of-concern-about-human-rights-in-hong-kong-and-xinjiang/.

- ↑ "Finland: 70th anniversary of diplomatic relations". 27 June 2012. http://www.lastampa.it/2012/06/27/vaticaninsider/eng/world-news/finland-th-anniversary-of-diplomatic-relations-7LzYbhOlJgVcSjyYvPcC5M/pagina.html.

- ↑ "#RepúblicaDominicana y la #SantaSede celebran hoy 16 de junio, 67 años de amistad." (in es). 16 June 2021. https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=4219188361476236&id=150790758316037&set=a.1849085921819837.

- ↑ "Iceland - Establishment of Diplomatic Relations". https://www.government.is/ministries/ministry-for-foreign-affairs/protocol/establishment-of-diplomatic-relations/.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Diplomatic relations between Holy See and ...". https://digitallibrary.un.org/search?ln=en&as=1&m1=p&p1=Diplomatic+relations+between+Holy+See+and+...&f1=series&op1=a&m2=a&p2=&f2=&op2=a&m3=a&p3=&f3=&dt=&d1d=&d1m=&d1y=&d2d=&d2m=&d2y=&rm=&action_search=Search&sf=year&so=a&rg=50&c=United+Nations+Digital+Library+System&of=hb&fti=0&fti=0.

- ↑ "Vatican recognizes state of Palestine in new treaty". 13 May 2015. https://www.timesofisrael.com/vatican-recognizes-state-of-palestine-in-new-treaty/.

- ↑ "Note on the diplomatic relations of the Holy See, 09.01.2017". January 2017. https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2017/01/09/170109b.html.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Bilateral and Multilateral Relations of the Holy See, update on October 22, 2009". https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/secretariat_state/documents/rc_seg-st_20010123_holy-see-relations_en.html.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Informative Note on the Diplomatic Relations of the Holy See". https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2024/01/08/240108a.html.

- ↑ "The Permanent Observer Mission of the Holy See to the United Nations". https://holyseemission.org/contents//mission/diplomatic-relations-of-the-holy-see.php.

- ↑ https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2019/01/07/190107a.html=english%7Carchivedate=January 2019

- ↑ "5 Key stats on Vatican diplomacy". https://aleteia.org/2024/01/12/5-key-stats-on-vatican-diplomacy/.

- ↑ "Pope names first diplomatic representative to Vietnam". http://www.ncronline.org/news/global/pope-names-first-diplomatic-representative-vietnam.

- ↑ Elemedia S.p.A. - Area Internet. "The Holy See's Diplomatic Net. Latest Acquisition: Russia". http://chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it/articolo/1341731?eng=y.

- ↑ "Apostolic Delegations". http://www.gcatholic.org/dioceses/delegations.htm.

- ↑ American Samoa, French Polynesia, Guam, New Caledonia, Niue (dependent but self-governing), Norfolk Island, Northern Mariana Islands, Pitcairn Islands, Tokelau, U.S. Minor Outlying Islands, Wallis and Futuna

- ↑ The dependent territories/constituent countries/overseas departments Anguilla, Aruba, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Montserrat, Netherlands Antilles, Turks and Caicos Islands, and U.S. Virgin Islands.

- ↑ Note On Appointment Of Apostolic Delegate To Kosovo:"being completely distinct from considerations regarding juridical and territorial situations or any other question inherent to the diplomatic activity of the Holy See."

- ↑ Bozzato, Fabrizio (2019). "Holy See-China-Taiwan: A Cross-Strait Triangle". Stosunki Międzynarodowe – International Relations (Tamkang University) 55 (2): 7. doi:10.7366/020909612201901. http://www.irjournal.pl/Holy-See-China-Taiwan-A-Cross-Strait-Triangle,123954,0,2.html.

- ↑ "Holy See and Republic of South Sudan Establish Diplomatic Ties". Vatican Information Service. 22 February 2013. http://visnews-en.blogspot.co.at/2013/02/holy-see-and-republic-of-south-sudan.html.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "Israeli response to Vatican recognition of PA as a state 26 Jun 2015". https://mfa.gov.il/MFA/PressRoom/2015/Pages/Israeli-response-to-Vatican-recognition-of-PA-as-a-state-26-Jun-2015.aspx.

- ↑ "Comunicato della Sala Stampa: Allacciamento delle relazioni diplomatiche tra la Santa Sede e la Repubblica Islamica di Mauritania" (in it). Holy See Press Office. 9 December 2016. http://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/2016/12/09/0890/01975.html.

- ↑ "Holy See Press Office Communiqué: Establishment of diplomatic relations between the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the Holy See". Holy See Press Office. 4 May 2017. http://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2017/05/04/170504c.html.

- ↑ "Holy See and Sultanate of Oman establish full diplomatic relations". 23 February 2023. https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2023-02/holy-see-and-sultanate-of-oman-establish-diplomatic-relations.html.

- ↑ Magister, Sandro (14 January 2010). "The Holy See's Diplomatic Net. Latest Acquisition: Russia". www.chiesa. http://chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it/articolo/1341731?eng=y.

- ↑ Lazreg, Marnia (2007). Torture and the Twilight of Empire: from Algiers to Baghdad. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13135-1.

- ↑ url=Lateran Treaty, article 24

- ↑ Hofmann, Paul (12 March 1958). "Algerians Appeal to Vatican; New Peace Bid Made to Paris; Algeria Rebels in Plea to Pope". https://www.nytimes.com/1958/03/12/archives/algerians-appeal-to-vatican-new-peace-bid-made-to-paris-algeria.html.

- ↑ Horne, Alistair (1978). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954–1962. Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-61964-7. https://archive.org/details/savagewarofpeace00horn.

- ↑ "Holy See Press Office Communiqué: Audience with the Grand Imam Ahmed Al-Tayeb, Sheikh of Al-Azhar, and entourage, 15.11.2019". 15 November 2019. https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2019/11/15/191115i.html.

- ↑ Template:Catholic-hierarchy

- ↑ "Pope Francis is going to Kenya - and here's what people are talking about". https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/32933/pope-francis-is-going-to-kenya-and-heres-what-people-are-talking-about.

- ↑ Template:Catholic-hierarchy

- ↑ Template:Catholic-hierarchy

- ↑ Template:Catholic-hierarchy

- ↑ "Argentine Ministry of Foreign Relations and Cult: direction of the Argentine embassy to the Holy See". http://www.mrecic.gov.ar/portal/repre_argentinas/plantilla.php?id=83.

- ↑ "Argentine Ministry of Foreign Relations and Cult: Direction of the Holy See's embassy in Buenos Aires". http://www.mrecic.gov.ar/portal/guia-dip/rep-ext/embajada.php?pais=38.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.mfa.gov.bz/images/documents/DIPLOMATIC%20RELATIONS.pdf.

- ↑ "Bolivian 'communist crucifix' gift to pope surprises Vatican". 9 July 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pope-latam-bolivia-crucifix/bolivian-communist-crucifix-gift-to-pope-surprises-vatican-idUSKCN0PJ2R520150709.

- ↑ "Audience with the president of Bolivia, 15.04.2016". 15 April 2016. https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/en/bollettino/pubblico/2016/04/15/160415a.html.

- ↑ Cody, Edward (10 July 1991). "Mexico Inches Toward Closer Church Ties". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/mexico/stories/910710.htm. "Formal ties were cut in 1861 by a decree from Mexican president Benito Juarez that also ordered expulsion of the papal nuncio in the shortest time "absolutely necessary to prepare your trip.""

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". The New York Times. 15 February 1990. https://www.nytimes.com/1990/02/15/world/mexico-and-vatican-move-toward-restoring-ties.html. "After more than a century of estrangement, the Mexican Government and the Vatican are suddenly moving toward re-establishing formal diplomatic relations and are also having informal talks on restoring some civil rights to the Roman Catholic Church here." - ↑ Golden, Tim (22 September 1992). "Mexico and the Catholic Church Restore Full Diplomatic Ties". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/22/world/mexico-and-the-catholic-church-restore-full-diplomatic-ties.html. "Mexico and the Vatican re-established full diplomatic relations today after a break of more than 130 years, completing a reconciliation based on the Government's restoration of legal rights to religious groups earlier this year."

- ↑ "Apostolic Nunciature of the Holy See in Mexico City (in Spanish)". http://www.sre.gob.mx/acreditadas/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=143:111&catid=35.

- ↑ "Bienvenidos a la portada". http://embamex.sre.gob.mx/vaticano/.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Azerbaijan. "The Holy See". https://mfa.gov.az/en/content/241/the-holy-see.

- ↑ "Foreign Missions in Bangladesh". BangladeshOnline.com. http://www.bdonline.com/information/f_mission/foreign_missions.htm.

- ↑ David M. Cheney. "Indonesia (Nunciature) [Catholic-Hierarchy"]. http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxid.html.

- ↑ Israely, Jeff (26 November 2007). "Iran's Secret Weapon: The Pope". Time. http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1687445,00.html. Retrieved 14 June 2009. "... Iran, which has had diplomatic relations with the Holy See for 53 years ...".

- ↑ Moore, Malcolm (1 June 2008). "Pope Avoids Iran's Mahmoud Ahmadinejad". Daily Telegraph. London. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iran/2061633/Pope-avoids-Irans-Mahmoud-Ahmadinejad.html. "Relations between Iran and the Holy See are warming, and Mr Ahmadinejad said the Vatican was a “positive force for justice and peace” in April after meeting with the new nuncio to Iran, Archbishop Jean-Paul Gobel. Benedict is also thought to have the support of several leading Shia clerics, including Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in Iraq."

- ↑ "To the Ambassador of the State of Kuwait, 24 March 1973". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/speeches/1973/march/documents/hf_p-vi_spe_19730324_ambasciatore-kuwait_en.html.

- ↑ David M. Cheney. "Kuwait (Nunciature) [Catholic-Hierarchy"]. http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxkw.html.

- ↑ "Malaysia: 179th State with Diplomatic Ties to Holy See". ZENIT News Agency. 27 July 2011. http://www.zenit.org/article-33164?l=english.

- ↑ "Liste du Corps Diplomatique près Le Saint-Siège" (in fr). Holy See. 18 May 2012. https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/secretariat_state/2012/documents/rc_seg-st_20120518_cd.pdf.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 McElwee, Joshua (4 May 2017). "Vatican, Myanmar establish full relations after Francis-Suu Kyi meeting Thursday". National Catholic Reporter. https://www.ncronline.org/news/vatican/vatican-myanmar-establish-full-relations-after-francis-suu-kyi-meeting-thursday.

- ↑ David M. Cheney. "Pakistan (Nunciature) [Catholic-Hierarchy"]. http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxpk.html.

- ↑ "Apostolic Nunciature of Holy See (Vatican City) in Manila, Philippines". EmbassyPages.com. 8 September 2010. http://www.embassypages.com/missions/embassy19652/. "Head of Mission: Antonio Franco, Apostolic Nuncio."

- ↑ "Embassy of Philippines in Vatican, Holy See (Vatican City)". EmbassyPages.com. 8 September 2010. http://www.embassypages.com/missions/embassy10099/. "Head of Mission: Ms Leonida L. Vera, Ambassador"

- ↑ "Qatar and Vatican Establish Diplomatic Relations". ZENIT - The World Seen From Rome. 18 November 2002. http://www.zenit.org/en/articles/qatar-and-vatican-establish-diplomatic-relations.

- ↑ "Pontificate of His Holiness Pope John Paul II – 2000 March 4.". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/biography/documents/hf_jp-ii_bio_20000517_pontificate_en.html.

- ↑ David M. Cheney. "Korea (Nunciature) [Catholic-Hierarchy"]. http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxkr.html.

- ↑ "Vatican Information Service News Archives – Monday, 6 March 2000: John Paul II Welcomes First Head of State from Korea." Refers to two visits in text.

- ↑ "Mass for the canonization of Korean martyrs, Homily of John Paul II, 6 May 1984". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/homilies/1984/documents/hf_jp-ii_hom_19840506_martiri-coreani_en.html.

- ↑ VIS, Vatican Information Service. "VIS news - Holy See Press Office: Monday, March 06, 2000". https://visnews-en.blogspot.com/2000_03_06_archive.html.

- ↑ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea-Europe". http://www.mofa.go.kr/ENG/countries/europe/index.jsp?menu=m_30_40_10.

- ↑ David M. Cheney. "Syria (Nunciature) [Catholic-Hierarchy"]. http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxsy.html.

- ↑ Plett, Barbara (7 May 2001). "Mosque visit crowns Pope's tour". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/1316812.stm.

- ↑ "Assad Attended John Paul II's Funeral". 4 April 2005. http://www.asianews.it/index.php?l=en&art=2952&dos=47&size=A.

- ↑ "Apostolic Nunciature of Holy See (Vatican City) in Bangkok, Thailand". EmbassyPages.com. 8 September 2010. http://www.embassypages.com/missions/embassy15695/. "Head of Mission: vacant."

- ↑ "Embassy of Thailand in Rome, Italy". EmbassyPages.com. 8 September 2010. http://www.embassypages.com/missions/embassy13960/. "Head of Mission: Mr Vara-Poj Snidvongs, Ambassador"

- ↑ "Apostolic Nunciature Thailand". 19 May 2010. http://www.gcatholic.org/dioceses/nunciature/nunc168.htm.

- ↑ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Thailand. http://www.mfa.go.th/web/2168.php?id=781&nm=On%208%20July%202010,%20Archbishop%20Salvatore%20Pennacchio,%20Vatican%92s%20Apostolic%20Nuncio%20to%20Thailand,%20paid%20a%20courtesy%20call%20on%20Foreign%20Minister%20Kasit%20Piromya%20on%20the%20occasion%20of%20the%20completin%20of%20his%20mission%20in%20Thailand..

- ↑ "Erdogan and pope discuss Jerusalem as scuffles break out near Vatican". 5 February 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pope-turkey-idUSKBN1FP0ZY.

- ↑ "Vatican establishes diplomatic relations with UAE | News, Middle East | THE DAILY STAR". https://www.dailystar.com.lb//News/Middle-East/2007/Jun-01/72109-vatican-establishes-diplomatic-relations-with-uae.ashx.

- ↑ "Pope Francis makes first papal visit to Arab Gulf state". CNN. 6 December 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/03/middleeast/pope-francis-uae-visit-intl/index.html.

- ↑ Cardinale, Gianni (January/February 2006). A Catholic bishop in the cradle of Islam . 30 Days.

- ↑ "President Saleh meets Vatican Pope John Paul II". 27 November 2004. https://www.saba.ye/en/news82862.htm.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 "Vatican and Albania Establishing Relations". 8 September 1991. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/09/08/world/vatican-and-albania-establishing-relations.html.

- ↑ List of pastoral visits of Pope John Paul II outside Italy

- ↑ Catholic Church in Albania

- ↑ "Embassy of Vatican in Denmark". http://vatican.visahq.com/embassy/Denmark/.

- ↑ "Vatican Resists Drive to Canonise EU Founder", by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, 19 August 2004

- ↑ Luxmoore, Jonathan (7 May 2009). "Finding Catholic inspiration in the European Union". http://www.heraldmalaysia.com/news/Finding-Catholic-inspiration-in-the-European-Union-634-4-1.html.

- ↑ "Holy See and Finland: 70 Years of Diplomatic Relations". September 2012. https://insidethevatican.com/magazine/vatican-watch/holy-see-and-finland-70-years-of-diplomatic-relations/.

- ↑ "Pope meets the Ambassador of Finland". http://www.italianinsider.it/?q=node/3540.

- ↑ "New Ambassador to the Holy See". https://finlandabroad.fi/web/vat/current-affairs/-/asset_publisher/SKOF4bdzBzBF/content/new-ambassador-to-the-holy-see/384951.

- ↑ "Almanac". United Press International. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-52755180.html. "In 2001, Pope John Paul II flew to Greece to begin a journey retracing the steps of the Apostle Paul through historic lands. ..."

- ↑ "To the first Ambassador of Republic of Iceland, 3 December 1977". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/paul_vi/speeches/1977/december/documents/hf_p-vi_spe_19771203_ambasciatore-islanda_en.html.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 "Diplomatic and Consular Information for the Holy See". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. https://www.dfa.ie/embassies/irish-embassies-abroad/europe/holy-see/.

- ↑ Template:Catholic-hierarchy

- ↑ Template:Catholic-hierarchy

- ↑ "Apostolic Nunciature of The Holy See (Vatican City) in Warsaw, Poland". http://www.embassypages.com/missions/embassy16504/.

- ↑ Ambasciata della Repubblica di Polonia presso la Santa Sede (with map)

- ↑ "Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: direction of the Holy See's embassy in Belgrade". http://www.mfa.gov.rs/Embassies/vatikan/holly_see_e.html.

- ↑ "Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: direction of the Serbian embassy to the Holy See". http://www.mfa.gov.rs/Embassies/sveta_stolica/sveta_stolica_e.html.

- ↑ "Croatia: Myth and Reality". http://www.studiacroatica.org/libros/mythe/cro03.htm.

- ↑ GENOCCHI, Giovanni. Treccani.it.

- ↑ Template:Catholic-hierarchy

- ↑ Varfolomeyev, Oleg (23 June 2001). "CNN.com - Pope's Ukraine visit stirs protest - June 23, 2001". CNN (Cable News Network LP). http://edition.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/europe/06/23/pope.background/index.html.

- ↑ Horowitz, Jason (13 May 2023). "Zelensky Meets Pope and Meloni in Italy to Bolster Ukraine's Support". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/13/world/europe/zelensky-pope-francis-ukraine-war.html.

- ↑ Script error: No such module "cite".

- ↑ Script error: No such module "cite".

- ↑ Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Holy See Brief, http://www.dfat.gov.au/GEO/holy_see/holy_see_brief.html

- ↑ David M. Cheney. "New Zealand (Nunciature) [Catholic-Hierarchy"]. http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dxxnz.html.

- ↑ "Address to the Ambassador of New Zealand, 12 January 1984". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/speeches/1984/january/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_19840112_ambasciatore-nuova-zelanda_en.html.

- ↑ "Homily of the Holy Father in Christchurch's Cathedral - New Zealand". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/homilies/1986/documents/hf_jp-ii_hom_19861124_christchurch-cattedrale_en.html.

- ↑ "POPE IN NEW ZEALAND". 23 November 1986. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/11/23/world/pope-in-new-zealand.html.

- ↑ "Apostolic Nunciature of Papua New Guinea". http://www.gcatholic.org/dioceses/nunciature/nunc130.htm.

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 "Bilateral Relations of the Holy See". Holy See website. https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/secretariat_state/documents/rc_seg-st_20010123_holy-see-relations_en.html.

- ↑ "Member States". International Organization for Migration. http://www.iom.int/jahia/Jahia/member-states.

- ↑ "Comunicato della Santa Sede". https://press.vatican.va/content/salastampa/it/bollettino/pubblico/2021/06/01/0350/00761.html.

- ↑ "UN site on Permanent Missions". https://www.un.org/members/nonmembers.shtml.

- ↑ "Holy See's Presence in the International Organizations". https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/secretariat_state/documents/rc_seg-st_doc_20020422_tauran_en.html.

- ↑ "Membership Vatican City State". Interpol. http://www.interpol.int/Member-countries/Europe/Vatican-City-State.

- ↑ "Proposed envoy not accepted". 15 May 1973. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article110709654.

- ↑ "Vatican nixes Argentina's ambassador on grounds of divorce". http://ncronline.org/node/11574.

- ↑ "Vatican rejects France's new gay ambassador". http://ncronline.org/node/2074.

- ↑ Thavis, John (4 April 2009). "Vatican Dismisses Report That It Rejected US Ambassador Picks . Catholic News Service. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

External links

- Bilateral relations of the Holy See (official Vatican site)

- Lecture on Vatican diplomacy, by Archbishop Jean-Louis Tauran

- Diplomatic Relations Of The Holy See

Template:Foreign relations of the Holy See

|

KSF

KSF