God in Abrahamic religions

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 29 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 29 min

| Part of a series on |

| Theism |

|---|

Monotheism—the belief that there is only one deity—is a foundational tenet of the Abrahamic religions, which alike conceive God as the all-powerful and all-knowing deity[1] from whom Abraham received a divine revelation, according to their respective narratives.[2] The most prominent Abrahamic religions are Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.[3] They—alongside Samaritanism,[4] the Druze Faith,[5] the Baháʼí Faith,[3] and Rastafari movement[3]—all share a common belief in the Abrahamic God. Likewise, the Abrahamic religions share similar features distinguishing them from other categories of religions:[6]

- all of their theological traditions are, to some extent, influenced by the depiction of the God of Israel in the Hebrew Bible,[8] who is explicitly named Yahweh in Hebrew and Allah in Arabic;[12]

- all of them trace their roots to Abraham as a common genealogical and spiritual patriarch.[13]

In the Abrahamic tradition, God is one, eternal, omnipotent, omniscient, and the creator of the universe.[1] God is typically referred to with masculine grammatical articles and pronouns only,[1][14] and is further held to have the properties of holiness, justice, omnibenevolence, and omnipresence. Adherents of the Abrahamic religions believe God is also transcendent, meaning he is outside of both space and time and therefore not subject to anything within his creation, but at the same time a personal God: intimately involved, listening to individual prayer, and reacting to the actions of his creatures.

With regard to Christianity, religion scholars have differed on whether Mormonism belongs with mainstream Christian tradition as a whole (i.e., Nicene Christianity), with some asserting that it amounts to a distinct Abrahamic religion in itself due to noteworthy theological differences.[15][16] Rastafarianism, the heterogenous movement that originated in Jamaica in the 1930s, is variously classified by religion scholars as either an international socio-religious movement, a distinct Abrahamic religion, or a new religious movement.[17]

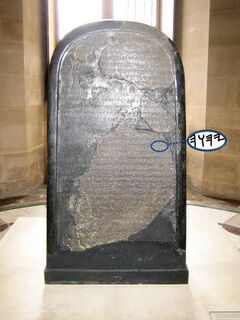

Judaism

Judaism, the oldest Abrahamic religion, is based on a strict, exclusive monotheism,[20] finding its origins in the sole veneration of Yahweh,[24] the predecessor to the Abrahamic conception of God.[Note 1] The names of God used most often in the Hebrew Bible are the Tetragrammaton (Hebrew: יהוה, romanized: YHWH) and Elohim.[9][10] Jews traditionally do not pronounce it, and instead refer to God as HaShem, literally "the Name". In prayer, the Tetragrammaton is substituted with the pronunciation Adonai, meaning "My Lord".[31] This is referred to primarily in the Torah: "Hear O Israel: the LORD is our God, the LORD is One" (Deuteronomy 6:4).[31]

God is conceived as unique and perfect, free from all faults, deficiencies, and defects, and further held to be omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, and completely infinite in all of his attributes, who has no partner or equal, being the sole creator of everything in existence.[34] In Judaism, God is never portrayed in any image.[35] The idea of God as a duality or trinity is heretical in Judaism: it is considered akin to polytheism.[37] The Torah specifically forbade ascribing partners to share his singular sovereignty,[38] as he is considered to be the absolute one without a second, indivisible, and incomparable being, who is similar to nothing and nothing is comparable to him.[39] Thus, God is unlike anything in or of the world as to be beyond all forms of human thought and expression.[40]

God in Judaism is conceived as anthropomorphic,[41] unique, benevolent, eternal, the creator of the universe, and the ultimate source of morality.[43] Thus, the term God corresponds to an actual ontological reality, and is not merely a projection of the human psyche.[44] Traditional interpretations of Judaism generally emphasize that God is personal yet also transcendent and able to intervene in the world,[10] while some modern interpretations of Judaism emphasize that God is an impersonal force or ideal rather than a supernatural being concerned with the universe.[45]

Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Christianity originated in 1st-century Judea from a sect of apocalyptic Jewish Christians within the realm of Second Temple Judaism,[51] and thus shares most of its beliefs about God, including his omnipotence, omniscience, his role as creator of all things, his personality, immanence, transcendence and ultimate unity, with the innovation that Jesus of Nazareth is considered to be, in one way or another, the fulfillment of the ancient biblical prophecies about the Jewish Messiah, the completion of the Law of the prophets of Israel, the Son of God, and/or the incarnation of God himself as a human being.[53]

Most Christian denominations believe Jesus to be the incarnated Son of God, which is the main theological divergence with respect to the exclusive monotheism of the other Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Samaritanism, the Baháʼí Faith, and Islam.[55] Although personal salvation is implicitly stated in Judaism, personal salvation by grace and a recurring emphasis in orthodox theological beliefs is particularly emphasized in Christianity,[54] often contrasting this with a perceived over-emphasis in law observance as stated in Jewish law, where it is contended that a belief in an intermediary between man and God or in the multiplicity of persons in the Godhead is against the Noahide laws, and thus not monotheistic.[56] In mainstream Christianity, theology and beliefs about God are enshrined in the doctrine of monotheistic Trinitarianism, which holds that the three persons of the trinity are distinct but all of the same indivisible essence, meaning that the Father is God, the Holy Spirit is God, and the Son is God, yet there is one God as there is one indivisible essence.[59] These mainstream Christian doctrines were largely formulated at the Council of Nicaea and are enshrined in the Nicene Creed.[60] The Trinitarian view emphasizes that God has a will, and that God the Son has two natures, divine and human, though these are never in conflict but joined in the hypostatic union.[61]

Gnosticism

Gnosticism originated in the late 1st century CE in non-rabbinical Jewish and early Christian sects.[62] In the formation of Christianity, various sectarian groups, labeled "gnostics" by their opponents, emphasised spiritual knowledge (gnosis) of the divine spark within, over faith (pistis) in the teachings and traditions of the various communities of Christians.[67] Gnosticism presents a distinction between the highest, unknowable God, and the Demiurge, "creator" of the material universe.[69] The Gnostics considered the most essential part of the process of salvation to be this personal knowledge, in contrast to faith as an outlook in their worldview along with faith in the ecclesiastical authority.[70]

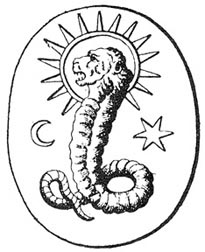

In Gnosticism, the biblical serpent in the Garden of Eden was praised and thanked for bringing knowledge (gnosis) to Adam and Eve and thereby freeing them from the malevolent Demiurge's control.[68] Gnostic Christian doctrines rely on a dualistic cosmology that implies the eternal conflict between good and evil, and a conception of the serpent as the liberating savior and bestower of knowledge to humankind opposed to the Demiurge or creator god, identified with the Hebrew God of the Old Testament.[71]

Gnostic Christians considered the Hebrew God of the Old Testament as the evil, false god and creator of the material universe, and the Unknown God of the Gospel, the father of Jesus Christ and creator of the spiritual world, as the true, good God.[73] In the Archontic, Sethian, and Ophite systems, Yaldabaoth (Yahweh) is regarded as the malevolent Demiurge and false god of the Old Testament who sinned by claiming divinity for himself and generated the material universe and keeps the souls trapped in physical bodies, imprisoned in the world full of pain and suffering that he created.[77]

However, not all Gnostic movements regarded the creator of the material universe as inherently evil or malevolent.[79] For instance, Valentinians believed that the Demiurge is merely an ignorant and incompetent creator, trying to fashion the world as good as he can, but lacking the proper power to maintain its goodness.[80] All Gnostics were regarded as heretics by the proto-orthodox Early Church Fathers.[82]

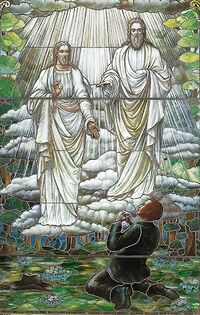

Mormonism

In the belief system held by the Christian churches that adhere to the Latter Day Saint movement and most Mormon denominations, including the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the term God refers to Elohim (God the Father),[85] whereas Godhead means a council of three distinct gods: Elohim (the Eternal Father), Jehovah (God the Son, Jesus Christ), and the Holy Ghost, in a Non-trinitarian conception of the Godhead.[86] The Father and Son have perfected, material bodies, while the Holy Ghost is a spirit and does not have a body.[87] This differs significantly from mainstream Christian Trinitarianism; in Mormonism, the three persons are considered to be physically separate beings, or personages, but united in will and purpose.[89] As such, the term Godhead differs from how it is used in mainstream Christianity.[90] This description of God represents the orthodoxy of the LDS Church, established early in the 19th century.[84]

Unitarianism

A small minority of Christians, largely coming under the headings of Unitarianism and Unitarian Universalism, hold Non-trinitarian conceptions of God.[91] Unitarian Christians affirm the unitary nature of God as the singular and unique creator of the universe,[91] believe that Jesus Christ was inspired by God in his moral teachings and that he is the savior of mankind,[91] but he is not equal to God himself. The churchmanship of Unitarianism generally reject the doctrine of original sin, and may include liberal denominations or Unitarian Christian denominations that are more conservative, with the latter being known as biblical Unitarians.[92][93]

The birth of the Unitarian faith is proximate to the Radical Reformation, beginning almost simultaneously among the Protestant[94] Polish Brethren in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and in the Principality of Transylvania in the mid-16th century;[95][96] the first Unitarian Christian denomination known to have emerged during that time was the Unitarian Church of Transylvania, founded by the Unitarian preacher and theologian Ferenc Dávid (c. 1520 – 1579).[95][96] As is typical of dissenters and nonconformists, Unitarianism does not constitute one single Christian denomination; rather, it refers to a collection of both existing and extinct Christian groups (whether historically related to each other or not) that share a common theological concept of the unitary nature of God.[91][92]

Islam

In Islam, God (Allah) (Arabic: ٱللَّٰه, romanized: Allāh, ar, lit. "the God")[11] is the supreme being, all-powerful and all-knowing creator, sustainer, ordainer, and judge of the universe.[99] Islam puts a heavy emphasis on the conceptualization of God as strictly singular (tawhid).[101] He is considered to be unique (wahid) and inherently one of them (ahad), all-merciful and omnipotent.[103] According to the Quran, there are 99 Names of God (al-asma al-husna, lit. meaning: "The best names") each of which evoke a distinct characteristic of God.[102] All these names refer to Allah, considered to be the supreme and all-comprehensive divine Arabic name.[102] Among the 99 names of God, the most famous and most frequent of these names are "the Entirely Merciful" (al-Rahman) and "the Especially Merciful" (al-Rahim).[102]

Islam rejects the doctrine of the Incarnation and the notion of a personal God as anthropomorphic, because it is seen as demeaning to the transcendence of God.[102] The Quran prescribes the fundamental transcendental criterion in the following verses: "The Lord of the heavens and the earth and what is between them, so serve Him and be patient in His service. Do you know any one equal to Him?" (19:65); "(He is) the Creator of the heavens and the earth: there is nothing whatever like unto Him, and He is the One that hears and sees (all things)" (42:11); "And there is none comparable unto Him" (112:4).[102] Therefore, Islam strictly rejects all forms of anthropomorphism and anthropopathism of the concept of God, and thus categorically rejects the Christian concept of the Trinity or division of persons in the Godhead.[106]

Muslims believe that Allah is the same God worshipped by the members of the Abrahamic religions that preceded Islam, i.e. Judaism and Christianity (29:46).[107] Creation and ordering of the universe is seen as an act of prime mercy for which all creatures sing his glories and bear witness to his unity and lordship. According to the Quran: "No vision can grasp Him, but His grasp is over all vision. He is above all comprehension, yet is acquainted with all things" (6:103).[98] Similarly to Jews, Muslims explicitly reject the divinity of Jesus and don't believe in him as the incarnated God or Son of God, but instead consider him a human prophet and the promised Messiah sent by God, although the Islamic tradition itself is not unanimous on the question of Jesus' death and afterlife.[111]

Baháʼí Faith

| Part of a series on |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

The writings of the Baháʼí Faith describe a monotheistic, personal, inaccessible, omniscient, omnipresent, imperishable, and almighty God who is the creator of all things in the universe.[112][113]: 106 The existence of God and the universe is thought to be eternal, without a beginning or end.[114]

Though transcendent and inaccessible directly,[115]: 438–446 God is nevertheless seen as conscious of the creation,[115]: 438–446 with a will and purpose that is expressed through messengers recognized in the Baháʼí Faith as the Manifestations of God[113]: 106 (all the Jewish prophets, Zoroaster, Krishna, the Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad, the Báb, and ultimately Baháʼu'lláh).[115]: 438–446 The purpose of the creation is for the created to have the capacity to know and love its creator,[113]: 111 through such methods as prayer, reflection, and being of service to humankind.[116] God communicates his will and purpose to humanity through his intermediaries, the prophets and messengers who have founded various world religions from the beginning of humankind up to the present day,[113]: 107–108 [115]: 438–446 and will continue to do so in the future.[115]: 438–446

The Manifestations of God reflect divine attributes, which are creations of God made for the purpose of spiritual enlightenment, onto the physical plane of existence.[117] In the Baháʼí view, all physical beings reflect at least one of these attributes, and the human soul can potentially reflect all of them.[118] The Baháʼí conception of God rejects all pantheistic, anthropomorphic, and incarnationist beliefs about God.[113]: 106

Rastafarianism

Rastafaris refer to God as Jah,[119][120][121] a shortened version of Jehovah in the Authorized King James Version.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Jah is said to be immanent,[122] but is also incarnate in each individual.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) This belief is reflected in the Rastafarian aphorism that "God is man and man is God".[123] Rastafaris describe "knowing" Jah, rather than simply "believing" in him.[124] In seeking to narrow the distance between humanity and divinity, Rastafaris embraces mysticism.[125] Closeness to Jah may be accomplished through Livity, a form of the Nazirite vow derived from the Old Testament.[126][127][128] The Rastafarian conception of God has similarities with the Hindu conception of soul (ātman).[129][130][131] Jesus is an important figure in Rastafari,[132] but practitioners reject the traditional Christian view of Jesus, and particularly the depiction of him as a White European.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Instead, many Rastafaris consider Haile Selassie I as the fulfillment of Psalm 68:31, and therefore the Messiah or Jah incarnate.[120]

See also

- Ancient Canaanite religion

- Ancient Semitic religion

- Argument from morality

- Atenism

- Comparative religion

- Conceptions of God

- Creationism

- Demiurge

- Dystheism

- Ethical monotheism

- Evil God Challenge

- False god

- God of Abraham (Yiddish prayer)

- God of Israel

- Mandaeism

- Misotheism

- Moralistic therapeutic deism

- Names of God

- Outline of theology

- Problem of evil

- Problem of Hell

- Religion in pre-Islamic Arabia

- Satanic Verses

- Semitic Neopaganism

- Sky father

- Table of prophets of Abrahamic religions

- Theistic Satanism

- Theodicy

- Urmonotheismus (primitive monotheism)

- Violence in the Bible

- Violence in the Quran

Notes

- ↑ Although the Semitic god El is indeed the most ancient predecessor to the Abrahamic god,[25][26][27][28] this specifically refers to the ancient ideas Yahweh once encompassed in the Ancient Hebrew religion, such as being a storm- and war-god, living on mountains, or controlling the weather.[25][26][27][29][30] Thus, in this page's context, "Yahweh" is used to refer to God as conceived in the Ancient Hebrew religion, and should not be referenced when describing his later worship in today's Abrahamic religions.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Christiano, Kevin J.; Kivisto, Peter; Swatos, William H. Jr., eds (2015). "Excursus on the History of Religions". Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments (3rd ed.). Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press. pp. 254–255. doi:10.2307/3512222. ISBN 978-1-4422-1691-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=EYtjY7GJav4C&pg=PA254.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Noort, Ed (2010). "Abraham and the Nations". in Goodman, Martin; van Kooten, George H.; van Ruiten, Jacques T.A.G.M.. Abraham, the Nations, and the Hagarites: Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Perspectives on Kinship with Abraham. Themes in Biblical Narrative: Jewish and Christian Traditions. 13. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 3–33. doi:10.1163/9789004216495_003. ISBN 978-90-04-21649-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=U-R5DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Abulafia, Anna Sapir (23 September 2019). "The Abrahamic religions". London: British Library. https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-abrahamic-religions.

- ↑ Kartveit, Magnar (2009). The Origin of the Samaritans. Vetus Testamentum, Supplements. 128. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 351–370. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004178199.i-406.63. ISBN 978-90-47-44054-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=lZSl64Or5UMC&pg=PA351.

- ↑ Abu-Izzeddin, Nejla M. (1993) [1984]. "Al-Ḥākim Bi-Amr Allāh". The Druzes: A New Study of Their History, Faith, and Society. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 74–86. doi:10.1163/9789004450349_011. ISBN 978-90-04-45034-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=CvT7EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA74.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bremer, Thomas S. (2015). "Abrahamic religions". Formed From This Soil: An Introduction to the Diverse History of Religion in America. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 19–20. doi:10.1002/9781394260959. ISBN 978-1-4051-8927-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=GE3YBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA19.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hughes, Aaron W. (2012). "What Are "Abrahamic Religions"?". Abrahamic Religions: On the Uses and Abuses of History. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 15–33. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199934645.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-993464-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=0K3Ia1rQCZEC&pg=PA15.

- ↑ [1][2][3][6][7]

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 Berlin, Adele, ed (2011). "GOD". The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion (2nd ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 294–297. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199730049.001.0001. ISBN 9780199759279. https://books.google.com/books?id=hKAaJXvUaUoC&pg=PA294.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Conditional Presence: The Meaning of the Name YHWH in the Bible". Understanding YHWH: The Name of God in Biblical, Rabbinic, and Medieval Jewish Thought. Jewish Thought and Philosophy (1st ed.). Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2019. pp. 25–63. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-32312-7_2. ISBN 978-3-030-32312-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=XKjDDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P. et al., eds (1960). "Allāh". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. 1. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0047. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

- ↑ [2][3][9][10][11]

- ↑ [1][2][3][6][7]

- ↑ "Masculine God Imagery and Sense of Life Purpose: Examining Contingencies with America's "Four Gods"". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion) 63 (1): 76–102. March 2024. doi:10.1111/jssr.12881. ISSN 1468-5906.

- ↑ Eliason, Eric A., ed (2001). "Is Mormonism Christian? Reflections on a Complicated Question". Mormons and Mormonism: An Introduction to an American World Religion. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 76–98. ISBN 978-0-252-02609-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=jsokQJDKJ7cC&pg=PA76.

- ↑ "Mormonism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 3 September 2015. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.75. ISBN 978-0-19-934037-8. https://oxfordre.com/religion/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-75. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Chryssides, George D. (2001). "Independent New Religions: Rastafarianism". Exploring New Religions. Issues in Contemporary Religion. London and New York: Continuum International. pp. 269–277. doi:10.2307/3712544. ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6. OCLC 436090427. https://books.google.com/books?id=S4_rodMYMygC&pg=PA269.

- ↑ ""House of David" Restored in Moabite Inscription". Biblical Archaeology Review (Washington, D.C.: Biblical Archaeology Society) 20 (3). May–June 1994. ISSN 0098-9444. http://www.cojs.org/pdf/house_of_david.pdf.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 Asif, Agha, ed (Spring 2016). "Smashing Idols: A Paradoxical Semiotics". Signs and Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Semiosis Research Center at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) 4 (1): 30–56. doi:10.1086/684586. ISSN 2326-4489. https://iris.unito.it/retrieve/handle/2318/1561609/136254/Massimo%20Leone%202016%20-%20Smashing%20Idols.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ↑ [9][19]

- ↑ Van der Toorn 1999, pp. 362–363.

- ↑ Betz 2000, pp. 916–917.

- ↑ Gruber, Mayer I. (2013). "Israel". in Spaeth, Barbette Stanley. The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–94. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139047784.007. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q1xbAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA76.

- ↑ [9][21][22][23]

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Stahl, Michael J. (2021). "The "God of Israel" and the Politics of Divinity in Ancient Israel". The "God of Israel" in History and Tradition. Vetus Testamentum: Supplements. 187. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 52–144. doi:10.1163/9789004447721_003. ISBN 978-90-04-44772-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=drMlEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA52.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Smith, Mark S. (2003). "El, Yahweh, and the Original God of Israel and the Exodus". The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 133–148. doi:10.1093/019513480X.003.0008. ISBN 978-0-19-513480-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=afkRDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA133.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Smith, Mark S. (2000). "El". in Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C.. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 384–386. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=qRtUqxkB7wkC&pg=PA384.

- ↑ Van der Toorn 1999, pp. 352–365.

- ↑ Niehr 1995, pp. 63–65, 71–72.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Van der Toorn 1999, pp. 361–362.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Moberly, R. W. L. (1990). ""Yahweh is One": The Translation of the Shema". in Emerton, J. A.. Studies in the Pentateuch. Vetus Testamentum: Supplements. 41. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 209–215. doi:10.1163/9789004275645_012. ISBN 978-90-04-27564-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=QZs3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA209.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Kittle, Simon; Gasser, Georg, eds (2022). "Is God a Person? Maimonidean and Neo-Maimonidean Perspectives". The Divine Nature: Personal and A-Personal Perspectives (1st ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 90–95. doi:10.4324/9781003111436. ISBN 9780367619268. https://books.google.com/books?id=wYlUEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT90.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 "Les dieux des autres: entre «démons» et «idoles»" (in fr). L'imaginaire du démoniaque dans la Septante: Une analyse comparée de la notion de "démon" dans la Septante et dans la Bible Hébraïque. Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism. 197. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. 2021. pp. 184–224. doi:10.1163/9789004468474_008. ISBN 978-90-04-46847-4.

- ↑ [9][31][32][33]

- ↑ [19][33]

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Bernard, David K. (2019). "Monotheism in Paul's Rhetorical World". The Glory of God in the Face of Jesus Christ: Deification of Jesus in Early Christian Discourse. Journal of Pentecostal Theology: Supplement Series. 45. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 53–82. ISBN 978-90-04-39721-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=0AD1DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA53.

- ↑ [9][19][33][36]

- ↑ [9][19][31]

- ↑ [9][32]

- ↑ [9][32]

- ↑ [9][30][36]

- ↑ Nikiprowetzky, V. (Spring 1975). "Ethical Monotheism". Daedalus (MIT Press for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences) 104 (2): 69–89. ISSN 1548-6192. OCLC 1565785.

- ↑ [9][42]

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Tuling, Kari H., ed (2020). "PART 2: Does God Have a Personality—or Is God an Impersonal Force?". Thinking about God: Jewish Views. JPS Essential Judaism Series. Lincoln and Philadelphia: University of Nebraska Press/Jewish Publication Society. pp. 67–168. doi:10.2307/j.ctv13796z1.7. ISBN 978-0-8276-1848-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=EzfsDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA67.

- ↑ [9][44]

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). "At Polar Ends of the Spectrum: Early Christian Ebionites and Marcionites". Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 95–112. doi:10.1017/s0009640700110273. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=URdACxKubDIC&pg=PA95. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). "How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God? Approaches to Jesus-Devotion in Earliest Christianity". How on Earth Did Jesus Become a God? Historical Questions about Earliest Devotion to Jesus. Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cambridge, UK: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 13–55. ISBN 978-0-8028-2861-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Xi5xIxgnNgcC&pg=PA13. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ Freeman, Charles (2010). "Breaking Away: The First Christianities". A New History of Early Christianity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 31–46. doi:10.12987/9780300166583. ISBN 978-0-300-12581-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=5_in-6VLgRoC&pg=PA31. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ Wilken, Robert Louis (2013). "Beginning in Jerusalem". The First Thousand Years: A Global History of Christianity. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 6–16. ISBN 978-0-300-11884-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=iW1-JImrwQUC&pg=PA6. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ Krans, Jan; Lietaert Peerbolte, L. J.; Smit, Peter-Ben et al., eds (2013). "How Antichrist Defeated Death: The Development of Christian Apocalyptic Eschatology in the Early Church". Paul, John, and Apocalyptic Eschatology: Studies in Honour of Martinus C. de Boer. Novum Testamentum: Supplements. 149. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 238–255. doi:10.1163/9789004250369_016. ISBN 978-90-04-25026-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=MoKxIeOTkqYC&pg=PA238. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ [46][47][48][49][50]

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Feldt, Laura; Valk, Ülo, eds (2017). "The Process of Jesus' Deification and Cognitive Dissonance Theory". Numen (Leiden: Brill Publishers) 64 (2–3): 119–152. doi:10.1163/15685276-12341457. ISSN 0029-5973.

- ↑ [19][36][46][47][52]

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 Gunton, Colin E., ed (2001). "Part II: The content of Christian doctrine – The Triune God". The Cambridge Companion to Christian Doctrine. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–140. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521471184.009. ISBN 9781139000000. https://books.google.com/books?id=hvCmnn4Tq20C&pg=PA121.

- ↑ [19][36][52][54]

- ↑ "Jewish Concepts: The Seven Noachide Laws". Jewish Virtual Library. American–Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE). 2021. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-seven-noachide-laws. Retrieved 17 October 2021. "Even though the Talmud and Maimonides stipulate that a non-Jew who violated the Noachide laws was liable to capital punishment, contemporary authorities have expressed the view that this is only the maximal punishment. According to this view, there is a difference between Noachide law and halakhah. According to halakhah, when a Jew was liable for capital punishment it was a mandatory punishment, provided that all conditions had been met, whereas in Noachide law death is the maximal punishment, to be enforced only in exceptional cases. In view of the strict monotheism of Islam, Muslims were considered as Noachides whereas the status of Christians was a matter of debate. Since the late Middle Ages, however, Christianity too has come to be regarded as Noachide, on the ground that Trinitarianism is not forbidden to non-Jews.".

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Cunningham, Mary B.; Theokritoff, Elizabeth, eds (2010). "Part I: Doctrine and Tradition – God in Trinity". The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Christian Theology. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–62. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521864848.004. ISBN 9781139001977. https://books.google.com/books?id=jP2vivMSezMC&pg=PA49.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A., eds (2005). "Doctrine of the Trinity". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd Revised ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1652–1653. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192802903.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=fUqcAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA1652.

- ↑ [54][57][58]

- ↑ [54][57][58]

- ↑ [54][57][58]

- ↑ Magris, Aldo (2005). "Gnosticism: Gnosticism from its origins to the Middle Ages (further considerations)". in Jones, Lindsay. Macmillan Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan Inc.. pp. 3515–3516. ISBN 978-0028657332. OCLC 56057973.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 63.4 63.5 Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). "Christians "In The Know": The Worlds of Early Christian Gnosticism". Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 113–134. doi:10.1017/s0009640700110273. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=URdACxKubDIC&pg=PA113.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 64.4 Mitchell, Margaret M.; Young, Frances M., eds (2008). "Part V: The Shaping of Christian Theology – Monotheism and creation". The Cambridge History of Christianity, Volume 1: Origins to Constantine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 434–451, 452–456. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521812399.026. ISBN 9781139054836. https://books.google.com/books?id=6UTfmw_zStsC&pg=PA434.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Brakke, David (2010). The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 18–51. ISBN 9780674066038. https://books.google.com/books?id=3EQ1XwHg0o0C&pg=PA18.

- ↑ Layton, Bentley (1999). "Prolegomena to the Study of Ancient Gnosticism". in Ferguson, Everett. Doctrinal Diversity: Varieties of Early Christianity. Recent Studies in Early Christianity: A Collection of Scholarly Essays. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 106–123. ISBN 0-8153-3071-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=GC4vwTXJSaMC&pg=PA106.

- ↑ [63][64][65][66]

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 68.4 68.5 Kvam, Kristen E.; Schearing, Linda S.; Ziegler, Valarie H., eds (1999). "Early Christian Interpretations (50–450 CE)". Eve and Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Readings on Genesis and Gender. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 108–155. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2050vqm.8. ISBN 9780253212719. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ux3bSDa2rHkC&pg=PA108.

- ↑ [63][68][64][65]

- ↑ [63][68][64][65]

- ↑ [63][68]

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEB1911 - ↑ [63][68][64][72]

- ↑ "Part I: The Self-deifying Rebel – “I Am God and There is No Other!”: The Boast of Yaldabaoth". Desiring Divinity: Self-deification in Early Jewish and Christian Mythmaking. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 2016. pp. 47–65. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190467166.003.0004. ISBN 9780199967728. OCLC 966607824. https://books.google.com/books?id=HwcBDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA47.

- ↑ "Yaldabaoth: The Gnostic Female Principle in Its Fallenness". Novum Testamentum (Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers) 32 (1): 79–95. January 1990. doi:10.1163/156853690X00205. ISSN 0048-1009.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Arendzen, John Peter (1908). "Demiurge". in Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Arendzen, John Peter (1908). "Demiurge". in Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton.

- ↑ [74][75][76]

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Esler, Philip F., ed (2002). "Part IX: Internal Challenges – Gnosticism". The Early Christian World. Routledge Worlds (1st ed.). New York and London: Routledge. pp. 923–925. ISBN 9781032199344. https://books.google.com/books?id=6fyCAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA923.

- ↑ [72][78]

- ↑ [72][78]

- ↑ Brakke, David (2010). "Imagining "Gnosticism" and Early Christianities". The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 18–51. ISBN 9780674066038. https://books.google.com/books?id=3EQ1XwHg0o0C&pg=PA18.

- ↑ [63][68][64][81]

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 83.4 83.5 Ludlow, Daniel H., ed. (1992), "God the Father", Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 548–552, ISBN 978-0-02-879602-4, OCLC 24502140, https://eom.byu.edu/index.php/God_the_Father, retrieved 7 May 2021

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 84.3 84.4 84.5 Davies, Douglas J. (2003). "Divine–human transformations: God". An Introduction to Mormonism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–77. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511610028.004. ISBN 978-0-511-61002-8. OCLC 438764483. https://books.google.com/books?id=fw8DIziwEDsC&pg=PA67.

- ↑ [83][84]

- ↑ [83][84]

- ↑ [83][84]

- ↑ The term with its distinctive Mormon usage first appeared in Lectures on Faith (published 1834), Lecture 5 ("We shall in this lecture speak of the Godhead; we mean the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit."). The term Godhead also appears several times in Lecture 2 in its sense as used in the Authorized King James Version, meaning divinity.

- ↑ [83][84][88]

- ↑ [83][84]

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 91.2 91.3 Bremer, Thomas S. (2015). "Transcendentalism". Formed From This Soil: An Introduction to the Diverse History of Religion in America. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 235. doi:10.1002/9781394260959. ISBN 978-1-4051-8927-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=GE3YBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA235. Retrieved 2023-01-13. "Unitarian theology, which developed in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, included a critique of the traditional Christian theology of the Trinity, which regarded God as three distinct but unified beings—transcendent Creator God, human Savior God (i.e., Jesus Christ), and immanent Spiritual God (i.e., the Holy Spirit). Unitarians viewed this understanding of God as a later theological corruption, and they embraced a view of God as a singular, unified entity; in most Unitarian theological interpretations, Jesus Christ retains highest respect as a spiritual and moral teacher of unparalleled insight and sensitivity, but he is not regarded as divine, or at least his divine nature is not on the same level as the singular and unique Creator God."

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Larsen, Timothy (2011). "Unitarians: Mary Carpenter and the Sacred Writings". A People of One Book: The Bible and the Victorians. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 137–153. ISBN 978-0-19-161433-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=mGgVDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA137.

- ↑ Mandelbrote, Scott; Ledger-Lomas, Michael (2013). Dissent and the Bible in Britain, c. 1650–1950. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-19-960841-6. "Although a biblical Unitarian, Mary Carpenter was lifelong friends with James Martineau, the pioneer of English liberal Unitarianism."

- ↑ Lerski, Jerzy Jan; Lerski, George J.; Lerski, Halina T. (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 978-0313260070. https://books.google.com/books?id=QTUTqE2difgC&dq=%22polish+brethren%22+%22protestant%22&pg=PA16. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Luszczynska, Magdalena (2018). "Introduction". Politics of Polemics: Marcin Czechowic on the Jews. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1515/9783110586565-001. ISBN 9783110586565. https://books.google.com/books?id=mQh2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA6. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Williams, George Huntston (1995). "Chapter 28: The Rise of Unitarianism in the Magyar Reformed Synod in Transylvania". The Radical Reformation (3rd ed.). University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press. pp. 1099–1133. ISBN 978-0-943549-83-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=ppmYEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1099. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ↑ McAuliffe, Jane Dammen, ed (2006). "God and his Attributes". Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. II. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQCOM_00075. ISBN 978-90-04-14743-0.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Esposito, John L. (2016). Islam: The Straight Path (Updated 5th ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-063215-1.

- ↑ [11][97][98]

- ↑ Esposito, John L. (2016). Islam: The Straight Path (Updated 5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-19-063215-1.

- ↑ [11][100]

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 102.3 102.4 102.5 "Chapter 10: God". An Introduction to Islam for Jews. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Jewish Publication Society. 2008. pp. 79–83. ISBN 9780827610491. https://books.google.com/books?id=9aqo0scH9n0C&pg=PA79.

- ↑ [11][102]

- ↑ Zulfiqar Ali Shah (2012). Anthropomorphic Depictions of God: The Concept of God in Judaic, Christian, and Islamic Traditions: Representing the Unrepresentable. International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT). pp. 48–56. ISBN 978-1-56564-583-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=164ZDAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ The Different Aspects of Islamic Culture: The Foundations of Islam. 1. UNESCO Publishing. 2016. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-92-3-104258-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Zcd7DQAAQBAJ.

- ↑ [104][105]

- ↑ F.E. Peters, Islam, p.4, Princeton University Press, 2003

- ↑ Stausberg, Michael; Engler, Steven, eds (March 2021). "'It was made to appear to them so': the Crucifixion, Jews, and Sasanian war propaganda in the Qur'ān". Religion (Taylor & Francis) 51 (3): 404–422. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2021.1909170. ISSN 1096-1151. OCLC 186359943.

- ↑ Reynolds, Gabriel S. (May 2009). "The Muslim Jesus: Dead or Alive?". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) 72 (2): 237–258. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09000500. https://www3.nd.edu/~reynolds/index_files/jesus%20dead%20or%20alive.pdf. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ↑ Robinson, Neal (1991). "The Crucifixion – Non-Muslim Approaches". Christ in Islam and Christianity: The Representation of Jesus in the Qur'an and the Classical Muslim Commentaries. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. pp. 106–140. ISBN 978-0-7914-0558-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=ht1hpisBQF0C&pg=PA106.

- ↑ [108][109][110]

- ↑ Hatcher, William S.; Martin, J. Douglas (1985). The Baháʼí Faith. San Francisco: Harper & Row. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-06-065441-2. https://archive.org/details/bahfaithemer00hatc/page/74.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 113.3 113.4 Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

- ↑ Britannica (1992). "The Baháʼí Faith". Britannica Book of the Year. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica. ISBN 978-0-85229-486-4. https://archive.org/details/1988britannicabo0000daum.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 115.2 115.3 115.4 Cole, Juan (30 December 2012). "BAHAISM i. The Faith". Encyclopædia Iranica. III/4. New York: Columbia University. pp. 438–446. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_6391. https://iranicaonline.org/articles/bahaism-i. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Hatcher, John S. (2005). "Unveiling the Hurí of Love". The Journal of Baháʼí Studies 15: –38. https://bahai-library.com/hatcher_unveiling_huri_love. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- ↑ Hatcher, William S.; Martin, J. Douglas (1985). The Baháʼí Faith. San Francisco: Harper & Row. pp. 123–126. ISBN 978-0-06-065441-2. https://archive.org/details/bahfaithemer00hatc/page/123.

- ↑ Saiedi, Nader (2008). Gate of the Heart. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 163–180. ISBN 978-1-55458-035-4. https://archive.org/details/gateheartunderst00saie/page/n171.

- ↑ Clarke 1986.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Murrell, Nathaniel Samuel. "Tuning Hebrew psalms to reggae rhythms: Rastas' revolutionary lamentations for social change." CrossCurrents (2000): pp. 525-540. Quotes: "The Psalms gave the Rastas the trademark name 'JAH' for their hero and deity, Ras Tafari, Emperor Haile Selassie I; the title JAH is found once in the Psalms as an abbreviation for Yahweh (or Jahweh), the four-letter word (tetragrammaton) YHWH. Psalm 68:4 reads, 'Sing unto God, sing praises to His name: extol him that rideth upon the heavens by his name JAH, and rejoice in him.'" "To Leonard Howell, one of the Jamaican pioneers of Rastafari, the prophetic declaration in Psalm 68:31—'Princes shall come out of Egypt; Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God'—was an indispensable paradigm for positing the messianic fulfillment of the Bible in the person of Haile Selassie I."

- ↑ Tomei, Renato. "Relocating a Sacred Space: From Mount Zion to the New Jerusalem in the Mystic Poetry of Rastafari." English Academy Review 40, no. 1 (2023): pp. 99-116.

- ↑ Chevannes 1990, p. 135.

- ↑ Edmonds 2012, p. 36.

- ↑ Clarke 1986, p. 65.

- ↑ Edmonds 2012, p. 92.

- ↑ Capparella, H., 2016. "Rastafari in the Promised Land." Antrocom: Online Journal of Anthropology, 12(1).

- ↑ Werden-Greenfield, A.Y. (2016), Warriors and prophets of livity: Samson and Moses as moral exemplars in Rastafari, Temple University

- ↑ Chakravarty, K.G. (2015). "Rastafari revisited: A four-point orthodox/secular typology". Journal of the American Academy of Religion 83 (1): 151-180.

- ↑ Stokke, C. (2021). "Consciousness development in Rastafari: A perspective from the psychology of religion". Anthropology of Consciousness 32 (1): 81-106.

- ↑ Chakravarty, K.G. (2015). "Rastafari revisited: A four-point orthodox/secular typology". Journal of the American Academy of Religion 83 (1): 151-180.

- ↑ Powell, Steven (1989). Dread rites: an account of Rastafarian music and ritual process in popular culture (Thesis). p. 31.

- ↑ Clarke 1986, p. 67.

Bibliography

- Barnett, Michael (2006). "Differences and Similarities Between the Rastafari Movement and the Nation of Islam". Journal of Black Studies (SAGE Publications) 36 (6): 873–893. doi:10.1177/0021934705279611. ISSN 1552-4566.

- Barrett, Leonard E. (1997). The Rastafarians. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-1039-6.

- Betz, Arnold Gottfried (2000). "Monotheism". in Freedman, David Noel; Myer, Allen C.. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 916–917. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=qRtUqxkB7wkC&pg=PA916.

- Bremer, Thomas S. (2015). "Abrahamic religions". Formed From This Soil: An Introduction to the Diverse History of Religion in America. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 19–20. doi:10.1002/9781394260959. ISBN 978-1-4051-8927-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=GE3YBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA19.

- Blidstein, Moshe; Silverstein, Adam J.; Stroumsa, Guy G., eds (2015). "Islamo-Christian Civilization". The Oxford Handbook of the Abrahamic Religions. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 109–120. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697762.013.6. ISBN 978-0-19-969776-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=_B2DCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA109.

- Byrne, Máire (2011). The Names of God in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam: A Basis for Interfaith Dialogue. London: Continuum International. ISBN 978-1-44116-3-417. https://books.google.com/books?id=ck4SBwAAQBAJ.

- Cashmore, E. Ellis (1983). Rastaman: The Rastafarian Movement in England (2nd ed.). London: Counterpoint. ISBN 978-0-04-301164-5.

- Chevannes, Barry (1990). "Rastafari: Towards a New Approach". New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 64 (3): 127–148. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002020.

- Christiano, Kevin J.; Kivisto, Peter; Swatos, William H. Jr., eds (2015). "Excursus on the History of Religions". Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments (3rd ed.). Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press. pp. 254–255. doi:10.2307/3512222. ISBN 978-1-4422-1691-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=EYtjY7GJav4C&pg=PA254.

- Clarke, Peter B. (1986). Black Paradise: The Rastafarian Movement. New Religious Movements Series. Wellingborough: The Aquarian Press. ISBN 978-0-85030-428-2.

- Cohen, Charles L. (2020). The Abrahamic Religions: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-065434-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=_dC8DwAAQBAJ.

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series. 265. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. doi:10.2307/3217888. ISBN 978-0-567-53783-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=2xadCgAAQBAJ&q=Kuntillet+Ajrud+Yahweh+and+his+asherah&pg=PA49.

- Edmonds, Ennis B. (2012). Rastafari: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958452-9.

- Fernández Olmos, Margarite; Paravisini-Gebert, Lizabeth (2011). Creole Religions of the Caribbean: An Introduction from Vodou and Santería to Obeah and Espiritismo (second ed.). New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6228-8.

- Hayes, Christine (2012). "Understanding Biblical Monotheism". Introduction to the Bible. The Open Yale Courses Series. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 15–28. ISBN 9780300181791.

- Hughes, Aaron W. (2012). "What Are "Abrahamic Religions"?". Abrahamic Religions: On the Uses and Abuses of History. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 15–33. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199934645.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-993464-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=0K3Ia1rQCZEC&pg=PA15.

- Niehr, Herbert (1995). "The Rise of YHWH in Judahite and Israelite Religion: Methodological and Religio-Historical Aspects". in Edelman, Diana Vikander. The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 45–72. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2. OCLC 33819403. https://books.google.com/books?id=bua2dMa9fJ4C&pg=PA45.

- "Part One: God – Chapter II: The Biblical Belief in God". Introduction to Christianity (2nd Revised ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press. 2004. pp. 116–136. ISBN 9781586170295. https://books.google.com/books?id=LJlkwvExekkC&pg=PA116.

- Reynolds, Gabriel S. (2020). "God of the Bible and the Qur'an". Allah: God in the Qurʾān. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 203–253. doi:10.2307/j.ctvxkn7q4. ISBN 978-0-300-24658-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=sxHPDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA203.

- Römer, Thomas (2015). The Invention of God. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/9780674915732. ISBN 978-0-674-50497-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z59XCwAAQBAJ.

- Rubenstein, Hannah; Suarez, Chris (1994). "The Twelve Tribes of Israel: An Explorative Field Study". Religion Today 9 (2): 1–6. doi:10.1080/13537909408580708.

- Smith, Mark S. (2017). "YHWH's Original Character: Questions about an Unknown God". in Van Oorschot, Jürgen; Witten, Markus. The Origins of Yahwism. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 484. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 23–44. doi:10.1515/9783110448221-002. ISBN 978-3-11-042538-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=8LtGDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA23.

- Van der Toorn, Karel (1999). "God (I)". in Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter W.. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 352–365. doi:10.1163/2589-7802_DDDO_DDDO_Godi. ISBN 978-90-04-11119-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=yCkRz5pfxz0C&pg=PA352.

- Van der Horst, Pieter W. (1999). "God (II)". in Van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; Van der Horst, Pieter W.. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 365–370. doi:10.1163/2589-7802_DDDO_DDDO_Godii. ISBN 978-90-04-11119-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=yCkRz5pfxz0C&pg=PA365.

External links

- Abulafia, Anna Sapir (23 September 2019). "The Abrahamic religions". London: British Library. https://www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-abrahamic-religions.

- Amzallag, Nissim (August 2018). "Metallurgy, the Forgotten Dimension of Ancient Yahwism". University of Arizona. https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/2018/08/amz428015.

- Gaster, Theodor H. (26 November 2020). "Biblical Judaism (20th–4th century BCE)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Judaism/Biblical-Judaism-20th-4th-century-bce. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

|

KSF

KSF