Lech-Lecha

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 96 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 96 min

Lech-Lecha, Lekh-Lekha, or Lech-L'cha (לֶךְ-לְךָ leḵ-ləḵā — Hebrew for "go!" or "leave!", literally "go for you" — the fifth and sixth words in the parashah) is the third weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It constitutes Genesis 12:1–17:27. The parashah tells the stories of God's calling of Abram (who would become Abraham), Abram's passing off his wife Sarai as his sister, Abram's dividing the land with his nephew Lot, the war between the four kings and the five, the covenant between the pieces, Sarai's tensions with her maid Hagar and Hagar's son Ishmael, and the covenant of circumcision (בְּרִית מִילָה, brit milah).

The parashah is made up of 6,336 Hebrew letters, 1,686 Hebrew words, 126 verses, and 208 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews read it on the third Sabbath after Simchat Torah, in October or November.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashah Lech-Lecha has three "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashah Lech-Lecha has several further subdivisions, called "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within the open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions. The first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divides the first reading (עליה, aliyah). The second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah), covers the balance of the first and all of the second and third readings (עליות, aliyot). The third open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) spans the remaining readings (עליות, aliyot). Closed portion (סתומה, setumah) divisions further divide the fifth and sixth readings (עליות, aliyot).[3]

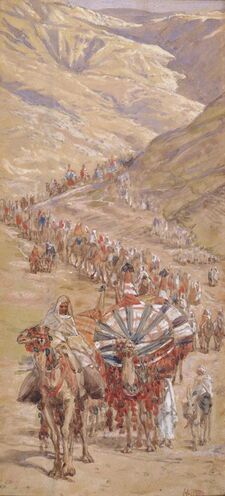

First reading — Genesis 12:1–13

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Abram to leave his native land and his father's house for a land that God would show him, promising to make of him a great nation, bless him, make his name great, bless those who blessed him, and curse those who cursed him.[4] Following God's command, at age 75, Abram took his wife Sarai, his nephew Lot, and the wealth and persons that they had acquired in Haran, and traveled to the terebinth of Moreh, at Shechem in Canaan.[5] God appeared to Abram to tell him that God would assign the land to his heirs, and Abram built an altar to God.[6] Abram then moved to the hill country east of Bethel and built an altar to God there and invoked God by name.[7] Then Abram journeyed toward the Negeb.[8] The first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[9]

In the continuation of the reading, famine struck the land, so Abram went down to Egypt, asking Sarai to say that she was his sister so that the Egyptians would not kill him.[10] The first reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[11]

Second reading — Genesis 12:14–13:4

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), when Abram and Sarai entered Egypt, Pharaoh's courtiers praised Sarai's beauty to Pharaoh, and she was taken into Pharaoh's palace. Pharaoh took Sarai as his wife.[12] Because of her, Abram acquired sheep, oxen, donkeys, slaves, and camels, but God afflicted Pharaoh and his household with mighty plagues.[13] Pharaoh questioned Abram why he had not told Pharaoh that Sarai was Abram's wife.[14] Pharaoh returned Sarai to Abram and had his men take them away with their possessions.[15] Abram, Sarai, and Lot returned to the altar near Bethel.[16] The second reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[17]

Third reading — Genesis 13:5–18

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), Abram and Lot now had so many sheep and cattle that the land could not support them both, and their herdsmen quarreled.[18] Abram proposed to Lot that they separate, inviting Lot to choose which land he would take.[19] Lot saw how well watered the plain of the Jordan was, so he chose it for himself, and journeyed eastward, settling near Sodom, a city of wicked sinners, while Abram remained in Canaan.[20] God promised to give all the land that Abram could see to him and his offspring forever, and to make his offspring as numerous as the dust of the earth.[21] Abram moved to the terebinths of Mamre in Hebron, and built an altar there to God.[22] The third reading (עליה, aliyah) and the second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here with the end of chapter 13.[23]

Fourth reading — Genesis 14:1–20

In the fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), in chapter 14, the Mesopotamian Kings Amraphel of Shinar, Arioch of Ellasar, Chedorlaomer of Elam, and Tidal of Goiim made war on the Canaanite kings of Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboiim, and Zoar, who joined forces at the Battle of Siddim, now the Dead Sea.[24] The Canaanite kings had served Chedorlaomer for twelve years, but rebelled in the thirteenth year.[25] In the fourteenth year, Chedorlaomer and the Mesopotamian kings with him went on a military campaign and defeated several peoples in and around Canaan: the Rephaim, the Zuzim, the Emim, the Horites, the Amalekites, and the Amorites.[26] Then the kings of Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboiim, and Zoar engaged the four Mesopotamian kings in battle in the Valley of Siddim.[27] The Mesopotamians routed the Canaanites, and the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah fled into bitumen pits in the valley, while the rest escaped to the hill country.[28] The Mesopotamians seized all the wealth of Sodom and Gomorrah, as well as Lot and his possessions, and departed.[29] A fugitive brought the news to Abram, who mustered his 318 retainers, and pursued the invaders north to Dan.[30] Abram and his servants defeated them at night, chased them north of Damascus, and brought back all the people and possessions, including Lot and his possessions.[31] When Abram returned, the king of Sodom came out to meet him in the Valley of Shaveh, the Valley of the King.[32] King Melchizedek of Salem (Jerusalem), a priest of God Most High, brought out bread and wine and blessed Abram and God Most High, and Abram gave him a tenth of everything.[33] The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[34]

Fifth reading — Genesis 14:21–15:6

In the fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), the king of Sodom offered Abram to keep all the possessions if he would merely return the people, but Abram swore to God Most High not to take so much as a thread or a sandal strap from Sodom, but would take only shares for the men who went with him.[35] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here with the end of chapter 14.[36]

As the reading (עליה, aliyah) continues in chapter 15, some time later, the word of God appeared to Abram, saying not to fear, for his reward would be very great, but Abram questioned what God could give him, as he was destined to die childless, and his steward Eliezer of Damascus would be his heir.[37] The word of God replied that Eliezer would not be his heir, Abram's own son would.[38] God took Abram outside and bade him to count the stars, for so numerous would his offspring be, and because Abram put his trust in God, God reckoned it to his merit.[39] The fifth reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[40]

Sixth reading — Genesis 15:7–17:6

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), God directed Abram to bring three heifers, three goats, three rams, a turtledove, and a bird, to cut the non-birds in two, and to place each half opposite the other.[41] Abram drove away birds of prey that came down upon the carcasses, and as the sun was about to set, he fell into a deep sleep.[42] God told Abram that his offspring would be strangers in a land not theirs, and be enslaved 400 years, but God would execute judgment on the nation they were to serve, and in the end they would go free with great wealth and return in the fourth generation, after the iniquity of the Amorites was complete.[43] And there appeared a smoking oven, and a flaming torch, which passed between the pieces.[44] And God made a covenant with Abram to assign to his offspring the land from the river of Egypt to the Euphrates: the land of the Kenites, the Kenizzites, the Kadmonites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Rephaim, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Girgashites, and the Jebusites.[45] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here with the end of chapter 15.[46]

As the reading continues in chapter 16, having borne no children after 10 years in Canaan, Sarai bade Abram to consort with her Egyptian maidservant Hagar, so that Sarai might have a son through her, and Abram did as Sarai requested.[47] When Hagar saw that she had conceived, Sarai was lowered in her esteem, and Sarai complained to Abram.[48] Abram told Sarai that her maid was in her hands, and Sarai treated her harshly, so Hagar ran away.[49] An angel of God found Hagar by a spring of water in the wilderness, and asked her where she came from and where she was going, and she replied that she was running away from her mistress.[50] The angel told her to go back to her mistress and submit to her harsh treatment, for God would make Hagar's offspring too numerous to count; she would bear a son whom she should name Ishmael, for God had paid heed to her suffering.[51] Ishmael would be a wild donkey of a man, with his hand against everyone, and everyone's hand against him, but he would dwell alongside his kinsmen.[52] Hagar called God "El-roi," meaning that she had gone on seeing after God saw her, and the well was called Beer-lahai-roi.[53] And when Abram was 86 years old, Hagar bore him a son, and Abram gave him the name Ishmael.[54] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here with the end of chapter 16.[55]

As the reading continues in chapter 17, when Abram was 99 years old, God appeared to Abram as El Shaddai and asked him to walk in God's ways and be blameless, for God would establish a covenant with him and make him exceedingly numerous.[56] Abram threw himself on his face, and God changed his name from Abram to Abraham, promising to make him the father of a multitude of nations and kings.[57] The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[58]

Seventh reading — Genesis 17:7–27

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), God promised to maintain the covenant with Abraham and his offspring as an everlasting covenant throughout the ages, and assigned all the land of Canaan to him and his offspring as an everlasting holding.[59] God further told Abraham that he and his offspring throughout the ages were to keep God's covenant and every male (including every slave) was to be circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin at the age of eight days as a sign of the covenant with God.[60] If any male failed to circumcise the flesh of his foreskin, that person was to be cut off from his kin for having broken God's covenant.[61] And God renamed Sarai as Sarah, and told Abraham that God would bless her and give Abraham a son by her so that she would give rise to nations and rulers.[62] Abraham threw himself on his face and laughed at the thought that a child could be born to a man of a hundred and a woman of ninety, and Abraham asked God to bless Ishmael.[63] But God told him that Sarah would bear Abraham a son, and Abraham was to name him Isaac, and God would maintain the everlasting covenant with him and his offspring.[64] In response to Abraham's prayer, God blessed Ishmael as well and promised to make him exceedingly numerous, the father of twelve chieftains and a great nation.[65] But God would maintain the covenant with Isaac, whom Sarah would bear at the same season the next year.[66] And when God finished speaking, God disappeared.[67] That very day, Abraham circumcised himself, Ishmael, and every male in his household, as God had directed.[68] The maftir (מפטיר) reading that concludes the parashah[69] reports that when Abraham circumcised himself and his household, Abraham was 99 and Ishmael was 13.[70] The seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), the third open portion (פתוחה, petuchah), chapter 17, and the parashah end here.[69]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[71]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017, 2019–2020 ... | 2017–2018, 2020–2021 ... | 2018–2019, 2021–2022 ... | |

| Reading | 12:1–13:18 | 14:1–15:21 | 16:1–17:27 |

| 1 | 12:1–3 | 14:1–9 | 16:1–6 |

| 2 | 12:4–9 | 14:10–16 | 16:7–9 |

| 3 | 12:10–13 | 14:17–20 | 16:10–16 |

| 4 | 12:14–20 | 14:21–24 | 17:1–6 |

| 5 | 13:1–4 | 15:1–6 | 17:7–17 |

| 6 | 13:5–11 | 15:7–16 | 17:18–23 |

| 7 | 13:12–18 | 15:17–21 | 17:24–27 |

| Maftir | 13:16–18 | 15:17–21 | 17:24–27 |

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[72]

Genesis chapter 12

Joshua 24:2 reports that Abram's father Terah lived beyond the River Euphrates and served other gods.

While Genesis 11:31 reports that Terah took Abram, Lot, and Sarai from Ur of the Chaldees to Haran, and Genesis 12:1 subsequently reports God's call to Abram to leave his country and his father's house, Nehemiah 9:7 reports that God chose Abram and brought him out of Ur of the Chaldees.

God's blessing to Abraham in Genesis 12:3 that "all the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you," is paralleled by God's blessing to Abraham in Genesis 22:18 that "All the nations of the earth shall bless themselves by your descendants," and God's blessing to Jacob in Genesis 28:14 that "All the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you and your descendants," and fulfilled by Balaam's request in Numbers 23:10 to share Israel's fate.[73]

Genesis chapter 15

In Genesis 15:5, God promised that Abraham’s descendants would be as numerous as the stars of heaven. Similarly, in Genesis 22:17, God promised that Abraham’s descendants would be as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore. In Genesis 26:4, God reminded Isaac that God had promised Abraham that God would make his heirs as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 32:13, Jacob reminded God that God had promised that Jacob’s descendants would be as numerous as the sands. In Exodus 32:13, Moses reminded God that God had promised to make the Patriarch’s descendants as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 1:10, Moses reported that God had multiplied the Israelites until they were then as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 10:22, Moses reported that God had made the Israelites as numerous as the stars. And Deuteronomy 28:62 foretold that the Israelites would be reduced in number after having been as numerous as the stars.

While Leviticus 12:6–8 required a new mother to bring a burnt-offering and a sin-offering, Genesis 15:2 and 1 Samuel 1:5–11 characterize childlessness as a misfortune; Leviticus 26:9, Deuteronomy 28:11, and Psalm 127:3–5 make clear that having children is a blessing from God; and Leviticus 20:20 and Deuteronomy 28:18 threaten childlessness as a punishment.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[74]

Genesis chapter 12

The second century BCE Book of Jubilees reported that Abraham endured ten trials and was found faithful and patient in spirit. Jubilees listed eight of the trials: (1) leaving his country, (2) the famine, (3) the wealth of kings, (4) his wife taken from him, (5) circumcision, (6) Hagar and Ishmael driven away, (7) the binding of Isaac, and (8) buying the land to bury Sarah.[75]

Acts 7:2–4 reported that God appeared to Abram while he was still in Mesopotamia, before he lived in Haran, and told him to leave his country and his people, and then he left the land of the Chaldeans to settle in Haran. And then after Terah's death, God sent Abraham to Canaan.

Philo interpreted Abram's migration allegorically as the story of a soul devoted to virtue and searching for God.[76]

The Apocalypse of Abraham told that Abraham argued to his father Terah that fire is more worthy of honor than idols, because its flames mock perishable things. Even more worthy of honor was water, because it conquers the fire and satisfies the earth. He called the earth more worthy of honor, because it overpowers the nature of the water. He called the sun more worthy of honor, because its rays illumine the whole world. But even the sun Abraham did not call god, because at night and by clouds it is obscured. Nor did Abraham call the moon or the stars god, because they also in their season obscure their light. Abraham argued to his father that they should worship the God who made everything, including the heavens, the sun, the moon, the stars, and the earth. And while Abraham thus spoke to his father in the court of his house, the voice of God came down from heaven in a fiery cloudburst, crying to Abraham to leave his father's house so that he would not also die in his father's sins.[77]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[78]

Genesis chapter 12

The Mishnah taught that Abraham suffered ten trials and withstood them all, demonstrating how great Abraham's love was for God.[79] The Avot of Rabbi Natan taught [80] that two trials were at the time he was bidden to leave Haran,[81] two were with his two sons,[82] two were with his two wives,[83] one was in the wars of the Kings,[84] one was at the covenant between the pieces,[85] one was in Ur of the Chaldees (where, according to a tradition, he was thrown into a furnace and came out unharmed[86]), and one was the covenant of circumcision.[87] Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer counted as the ten trials: (1) when Abram was a child and all the magnates of the kingdom and the magicians sought to kill him (see below), (2) when he was put into prison for ten years and cast into the furnace of fire, (3) his migration from his father's house and from the land of his birth, (4) the famine, (5) when Sarah his wife was taken to be Pharaoh's wife, (6) when the kings came against him to slay him, (7) when (in the words of Genesis 17:1) "the word of the Lord came to Abram in a vision," (8) when Abram was 99 years old and God asked him to circumcise himself, (9) when Sarah asked Abraham (in the words of Genesis 21:10) to "Cast out this bondwoman and her son," and (10) the binding of Isaac.[88]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that the first trial was when Abram was born, and all the magnates of the kingdom and the magicians sought to kill him. Abram's family hid Abram in a cave for 13 years, during which he never saw the sun or moon. After 13 years, Abram came out speaking the holy language, Hebrew, and he despised idols and held in abomination the graven images, and he trusted in God, saying (in the words of Psalm 84:12): "Blessed is the man who trusts in You." In the second trial, Abram was put in prison for ten years — three years in Kuthi, seven years in Budri. After 10 years, they brought him out and cast him into the furnace of fire, and God delivered him from the furnace of fire, as Genesis 15:7 says, "And He said to him, 'I am the Lord who brought you out of the furnace of the Chaldees." Similarly, Nehemiah 9:7 reports, "You are the Lord the God, who did choose Abram, and brought him forth out of the furnace of the Chaldees." The third trial was Abram's migration from his father's house and from the land of his birth. God brought him to Haran, and there his father Terah died, and Athrai his mother. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that migration is harder for a human than for any other creature. And Genesis 12:1 tells of his migration when it says, "Now the Lord said to Abram, 'Get out.'"[89]

Rabbi Hiyya said that Abram's father Terah manufactured idols (as Joshua 24:2 implies), and once Terah went away and left Abram to mind the store. A man came and asked to buy an idol. Abram asked the man how old he was. The man replied that he was 50 years old. Abram exclaimed that it was a shame that a man of 50 would worship a day-old object. The man became embarrassed and left. On another occasion, a woman came with a plate of flour and asked Abram to offer it to the idols. Abram took a stick, broke the idols, and put the stick in the largest idol's hand. When Terah returned, he demanded that Abram explain what he had done. Abram told Terah that the idols fought among themselves to be fed first, and the largest broke the others with the stick. Terah asked Abram why he made sport of him, for the idols had no consciousness. Abram replied by asking Terah to listen to what he had just said. Thereupon Terah seized Abram and delivered him to Nimrod, king of Shinar. Nimrod proposed that they worship the fire. Abram replied that they should rather worship water, which extinguishes fire. Nimrod agreed to worship water. Abram replied that they should rather worship clouds, which bear the water. Nimrod agreed to worship the clouds. Abram replied that they should rather worship the winds, which disperse the clouds. Nimrod agreed to worship the wind. Abram replied that they should rather worship human beings, who withstand the wind. Nimrod then accused Abram of just bandying words, and decreed that they would worship nothing but the fire. Nimrod cast Abram into the fire, challenging Abram's God to save him from it. Haran was standing there undecided. Haran thought to himself that if Abram survived, then Haran would say that he was of Abram's faith, but if Nimrod was victorious, then Haran would say that he was on Nimrod's side. When Abram descended into the fiery furnace, God saved him. Nimrod then asked Haran whose belief he shared. Haran replied that he shared Abram's faith. Thereupon Nimrod cast Haran into the fire, and he died in his father's presence, as Genesis 11:28 reports, "And Haran died in the presence of (עַל-פְּנֵי, al pene) his father Terah."[90]

Rabbi Aha said in the name of Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman (or others say Rabbi Alexandri's name) in Rabbi Nathan's name that Abraham knew (and observed) even the laws of the courtyard eruv. Rabbi Phinehas (and others say Rabbi Helkiah and Rabbi Simon) said in the name of Rabbi Samuel that Abraham knew even the new name that God will one day give to Jerusalem, as Jeremiah 3:17 says, "At that time they shall call Jerusalem 'The Throne of God.'" Rabbi Berekiah, Rabbi Hiyya, and the Rabbis of Babylonia taught in Rabbi Judah's name that a day does not pass in which God does not teach a new law in the heavenly Court. For as Job 37:2 says, "Hear attentively the noise of His voice, and the meditation that goes out of His mouth." And meditation refers to nothing but Torah, as Joshua 1:8 says, "You shall meditate therein day and night." And Abraham knew them all.[91]

Rabbi Isaac compared Abram's thinking to that of a man who was travelling from place to place when he saw a building in flames. He wondered whether it was possible that the building could lack a person to look after it. At that moment, the owner of the building appeared and said that he owned the building. Similarly, Abram questioned whether it was conceivable that the world could exist without a Guide to look after it. At that moment, God told Abram that God is the Guide, the Sovereign of the Universe. At that moment, in the words of Genesis 12:1, "The Lord said to Abraham: 'Get out of your country.'"[92]

A Midrash taught that when God spoke to Abram in Genesis 12:1, it was the first time that God had spoken to a person since Noah. Thus, the Midrash said that Ecclesiastes 7:19, "Wisdom makes a wise man stronger than ten rulers," refers to Abraham, whom wisdom made stronger than the ten generations from Noah to Abraham. For out of all of them, God spoke to Abraham alone.[93]

The Gemara reported that some deduced from Genesis 12:1–2 that change of place can cancel a man's doom, but another argued that it was the merit of the land of Israel that availed Abraham.[94]

Reading God's command to Abram in Genesis 12:1 to get out of his country along with Song of Songs 1:3, "Your ointments have a goodly fragrance," Rabbi Berekiah taught that before God called on Abram, Abram resembled a vial of myrrh closed with a tight-fitting lid and lying in a corner, so that its fragrance was not disseminated. As soon as the vial was taken up, however, its fragrance was disseminated. Similarly, God commanded Abraham to travel from place to place, so that his name would become great in the world.[95]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that the five Hebrew letters of the Torah that alone among Hebrew letters have two separate shapes (depending whether they are in the middle or the end of a word) — צ פ נ מ כ (Kh, M, N, P, Z) — all relate to the mystery of the redemption. With the letter kaph (כ), God redeemed Abraham from Ur of the Chaldees, as in Genesis 12:1, God says, "Get you (לֶךְ-לְךָ, lekh lekha) out of your country, and from your kindred ... to the land that I will show you." With the letter mem (מ), Isaac was redeemed from the land of the Philistines, as in Genesis 26:16, the Philistine king Abimelech told Isaac, "Go from us: for you are much mightier (מִמֶּנּוּ, מְאֹד, mimenu m'od) than we." With the letter nun (נ), Jacob was redeemed from the hand of Esau, as in Genesis 32:12, Jacob prayed, "Deliver me, I pray (הַצִּילֵנִי נָא, hazileini na), from the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esau." With the letter pe (פ), God redeemed Israel from Egypt, as in Exodus 3:16–17, God told Moses, "I have surely visited you, (פָּקֹד פָּקַדְתִּי, pakod pakadeti) and (seen) that which is done to you in Egypt, and I have said, I will bring you up out of the affliction of Egypt." With the letter tsade (צ), God will redeem Israel from the oppression of the kingdoms, and God will say to Israel, I have caused a branch to spring forth for you, as Zechariah 6:12 says, "Behold, the man whose name is the Branch (צֶמַח, zemach); and he shall grow up (יִצְמָח, yizmach) out of his place, and he shall build the temple of the Lord." These letters were delivered to Abraham. Abraham delivered them to Isaac, Isaac delivered them to Jacob, Jacob delivered the mystery of the Redemption to Joseph, and Joseph delivered the secret of the Redemption to his brothers, as in Genesis 50:24, Joseph told his brothers, "God will surely visit (פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד, pakod yifkod) you." Jacob's son Asher delivered the mystery of the Redemption to his daughter Serah. When Moses and Aaron came to the elders of Israel and performed signs in their sight, the elders told Serah. She told them that there is no reality in signs. The elders told her that Moses said, "God will surely visit (פָּקֹד יִפְקֹד, pakod yifkod) you" (as in Genesis 50:24). Serah told the elders that Moses was the one who would redeem Israel from Egypt, for she heard (in the words of Exodus 3:16), "I have surely visited (פָּקֹד פָּקַדְתִּי, pakod pakadeti) you." The people immediately believed in God and Moses, as Exodus 4:31 says, "And the people believed, and when they heard that the Lord had visited the children of Israel."[96]

Rabbi Berekiah noted that in Genesis 12:2, God had already said, "I will bless you," and so asked what God added by then saying, "and you be a blessing." Rabbi Berekiah explained that God was thereby conveying to Abraham that up until that point, God had to bless God's world, but thereafter, God entrusted the ability to bless to Abraham, and Abraham could thenceforth bless whomever it pleased him to bless.[97]

Rabbi Nehemiah said that the power of blessing granted to Abraham in Genesis 12:2 was what Abraham gave to Isaac in Genesis 25:5. But Rabbi Judah and the Rabbis disagreed.[98]

Rav Nahman bar Isaac deduced from God's promise to Abraham in Genesis 12:3, "And I will bless them that bless you," that since the priests (כֹּהֲנִים, kohanim) bless Abraham's descendants with the Priestly Blessing of Numbers 6:23–27, God therefore blesses the priests.[99]

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words, "And in you shall the families of the earth be blessed (וְנִבְרְכוּ, venivrechu)" in Genesis 12:3 to teach that God told Abram that God had two good shoots to graft (lihavrich) onto Abram's family tree: Ruth the Moabitess (whom Ruth 4:13–22 reports was the ancestor of David) and Naamah the Ammonitess (whom 1 Kings 14:21 reports was the mother of Rehoboam and thus the ancestor or good kings like Hezekiah). And Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words, "All the families of the earth," in Genesis 12:3 to teach that even the other families who live on the earth are blessed only for Israel's sake.[100]

Rav Judah deduced from Genesis 12:3 that to refuse to say grace when given a cup to bless is one of three things that shorten a man's life.[101] And Rabbi Joshua ben Levi deduced from Genesis 12:3 that every kohen who pronounces the benediction is himself blessed.[102]

Resh Lakish deduced from Genesis 12:5 that the Torah regards the man who teaches Torah to his neighbor's son as though he had fashioned him.[103]

Similarly, Rabbi Leazar in the name of Rabbi Jose ben Zimra observed that if all the nations assembled to create one insect they could not bring it to life, yet Genesis 12:5 says, "the souls whom they had made in Haran." Rabbi Leazar in the name of Rabbi Jose ben Zimra interpreted the words "the souls whom they had made" to refer to the proselytes whom Abram and Sarai had converted. The Midrash asked why then Genesis 12:5 did not simply say, "whom they had converted," and instead says, "whom they had made." The Midrash answered that Genesis 12:5 thus teaches that one who brings a nonbeliever near to God is like one who created a life. Noting that Genesis 12:5 does not say, "whom he had made," but instead says "whom they had made," Rabbi Hunia taught that Abraham converted the men, and Sarah converted the women.[104]

Rabbi Haggai said in Rabbi Isaac's name that all of the Matriarchs were prophets.[105]

The Tanna debe Eliyyahu taught that the world is destined to exist for 6,000 years. The first 2,000 years were to be void, the next 2,000 years were the period of the Torah, and the last 2,000 years are the period of the Messiah. And the Gemara taught that the 2,000 years of the Torah began when, as Genesis 12:5 reports, Abraham and Sarah had gotten souls in Haran, when by tradition Abraham was 52 years old.[106]

The Mishnah equated the terebinth of Moreh to which Abram journeyed in Genesis 12:6 with the terebinths of Moreh to which Moses directed the Israelites to journey in Deuteronomy 11:30 to hear the blessings and curses at Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal,[107] and the Gemara equated both with Shechem.[108]

Rabbi Elazar said that one should always anticipate misfortune with prayer; for it was only by virtue of Abram's prayer between Bethel and Ai reported in Genesis 12:8 that Israel's troops survived at the Battle of Ai in the days of Joshua."[109]

The Rabbis deduced from Genesis 12:10 that when there is a famine in town, one should emigrate.[110]

Rabbi Phinehas commented in Rabbi Hoshaya's name that God told Abraham to go forth and tread out a path for his children, for everything written in connection with Abraham is written in connection with his children:[111]

| Verse | Abraham | Verse | The Israelites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genesis 12:10 | "And there was a famine in the land." | Genesis 45:6 | "For these two years has the famine been in the land." |

| Genesis 12:10 | "And Abram went down into Egypt." | Numbers 20:15 | "And our fathers went down into Egypt." |

| Genesis 12:10 | "To sojourn there" | Genesis 47:4 | "To sojourn in the land are we come." |

| Genesis 12:10 | "For the famine was sore in the land." | Genesis 43:1 | "And the famine was sore in the land." |

| Genesis 12:11 | "And it came to pass, when he came near (הִקְרִיב, hikriv) to enter into Egypt ..." | Exodus 14:10 | "And when Pharaoh drew near (הִקְרִיב, hikriv) ..." |

| Genesis 12:12 | "And they will kill me, but you they will keep alive." | Exodus 1:22 | "Every son that is born you shall cast into the river, and every daughter you shall save alive." |

| Genesis 12:13 | "Say, I pray you, that you are my sister, that it may be well with me." | Exodus 1:20 | "And God dealt well with the midwives." |

| Genesis 12:14 | "And it came to pass, that, when Abram had come into Egypt ..." | Exodus 1:1 | "Now these are the names of the sons of Israel, who came in Egypt ..." |

| Genesis 12:20 | "And Pharaoh gave men charge concerning him, and they sent him away." | Exodus 12:33 | "And the Egyptians were urgent upon the people, to send them out." |

| Genesis 13:2 | "And Abram was very rich in cattle, in silver, and in gold." | Psalm 105:37 | "And He brought them forth with silver and gold." |

| Genesis 13:3 | "And he went on his journeys." | Numbers 33:1 | "These are the journeys of the children of Israel." |

Similarly, Rabbi Joshua of Sikhnin taught that God gave Abraham a sign: Everything that happened to him would also happen to his children:[112]

| Verse | Abraham | Verse | The Israelites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nehemiah 9:7 | "You are the Lord the God, who did choose Abram, and brought him forth out of Ur of the Chaldees, and gave him the name of Abraham." | Deuteronomy 14:2 | "For you are a holy people to the Lord your God, and the Lord has chosen you to be His own treasure out of all peoples on the face of the earth." |

| Genesis 12:1 | "Go for yourself" | Exodus 3:17 | "I will bring you up out of the affliction of Egypt to the land of the Canaanite, and the Hittite, and the Amorite, and the Perizzite, and the Hivite, and the Jebusite, unto a land flowing with milk and honey." |

| Genesis 12:2–3 | "And I will bless you, and make your name great; and you will be a blessing. And I will bless them that bless you." | Numbers 6:24 | "The Lord bless you, and keep you." |

| Genesis 12:2 | "And I will make of you a great nation." | Deuteronomy 4:8 | "And what great nation is there ... ?" |

| Ezekiel 33:24 | "Abraham was [a unique] one." | 1 Chronicles 17:21 | "Who is like Your nation, Israel?" |

| Genesis 12:10 | "And there was a famine in the land; and Abram went down into Egypt to sojourn there; for the famine was severe in the land." | Genesis 43:1 | "The famine was severe in the land." |

| Genesis 12:10 | "Abram went down into Egypt." | Genesis 42:3 | "Joseph's ten brethren went down to buy grain from Egypt." |

| Genesis 12:14 | The Egyptians harassed Abraham: "The Egyptians beheld the woman that she was very fair." | Exodus 1:10 | The Egyptians harassed the Israelites: "Come, let us deal wisely with them ..." |

| Genesis 14 | The kings joined forces against Abraham. | Psalm 2:1–2 | The kings will join forces against Israel: "The kings of the earth stand up, and the rulers take counsel together, against the Lord, and against His anointed." |

| Isaiah 41:2 | God fought against Abraham's foes: "Who has raised up one from the east, at whose steps victory attends?" | Zechariah 14:3 | God will fight against Israel's foes: "Then shall the Lord go forth, and fight against those nations, as when He fought in the day of battle." |

Rav deduced from Genesis 12:11 that Abram had not even looked at his own wife before that point.[113]

Reading the words, "And it came to pass, that, when Abram came into Egypt," in Genesis 12:14, a Midrash asked why the text at that point mentioned Abraham but not Sarai. The Midrash taught that Abram had put Sarai in a box and locked her in. The Midrash told that when Abram came to the Egyptian customs house, the customs officer demanded that Abram pay the custom duty on the box and its contents, and Abram agreed to pay. The customs officer proposed that Abram must have been carrying garments in the box, and Abram agreed to pay the duty for garments. The customs officer then proposed that Abram must have been carrying silks in the box, and Abram agreed to pay the duty for silks. The customs officer then proposed that Abram must have been carrying precious stones in the box, and Abram agreed to pay the duty for precious stones. But then the customs officer insisted that Abram open the box so that the customs officers could see what it contained. As soon as Abram opened the box, Sarai's beauty illuminated the land of Egypt.[114]

Rabbi Azariah and Rabbi Jonathan in Rabbi Isaac's name taught that Eve's image was transmitted to the reigning beauties of each generation (setting the standard of beauty). 1 Kings 1:4 says of David's comforter Abishag, "And the damsel was very fair" — יָפָה עַד-מְאֹד, yafah ad me'od — which the Midrash interpreted to mean that she attained to Eve's beauty (as עַד-מְאֹד, ad me'od, implies אָדָם, Adam, and thus Eve). And Genesis 12:14 says, "the Egyptians beheld the woman that she was very fair" — מְאֹד, me'od — which the Midrash interpreted to mean that Sarai was even more beautiful than Eve. Reading the words, "And the princes of Pharaoh saw her, and praised her to Pharaoh," in Genesis 12:15, Rabbi Johanan told that they tried to outbid each other for the right to enter Pharaoh's palace with Sarai. One prince said that he would give a hundred dinars for the right to enter the palace with Sarai, whereupon another bid two hundred dinars.[115]

Rabbi Helbo deduced from Genesis 12:16 that a man must always observe the honor due to his wife, because blessings rest on a man's home only on account of her.[116]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that leprosy resulted from seven things: slander, bloodshed, vain oath, incest, arrogance, robbery, and envy. The Gemara cited God's striking Pharaoh with plagues in Genesis 12:17 to show that incest had led to leprosy.[117]

Genesis chapter 13

A Baraita deduced from the words, "like the garden of the Lord, like the land of Egypt," in Genesis 13:10 that among all the nations, there was none more fertile than Egypt. And the Baraita taught that there was no more fertile spot in Egypt than Zoan, where kings lived, for Isaiah 30:4 says of Pharaoh, "his princes are at Zoan." And in all of Israel, there was no more rocky ground than that at Hebron, which is why the Patriarchs buried their dead there, as reported in Genesis 49:31. But rocky Hebron was still seven times as fertile as lush Zoan, as the Baraita interpreted the words "and Hebron was built seven years before Zoan in Egypt" in Numbers 13:22 to mean that Hebron was seven times as fertile as Zoan. The Baraita rejected the plain meaning of "built," reasoning that Ham would not build a house for his younger son Canaan (in whose land was Hebron) before he built one for his elder son Mizraim (in whose land was Zoan, and Genesis 10:6 lists (presumably in order of birth) "the sons of Ham: Cush, and Mizraim, and Put, and Canaan."[118]

Rabbi Issi taught that there was no city in the plain better than Sodom, for Lot had searched through all the cities of the plain and found none like Sodom. Thus the people of Sodom were the best of all, yet as Genesis 13:13 reports, "the men of Sodom were wicked and sinners." They were "wicked" to each other, "sinners" in adultery, "against the Lord" in idolatry, and "exceedingly" engaged in bloodshed.[119]

The Mishnah deduced from Genesis 13:13 that the men of Sodom would have no place in the world to come.[120]

Genesis chapter 14

Rabbi Levi, or some say Rabbi Jonathan, said that a tradition handed down from the Men of the Great Assembly taught that wherever the Bible employs the term "and it was" or "and it came to pass" (וַיְהִי, wa-yehi), as it does in Genesis 14:1, it indicates misfortune, as one can read wa-yehi as wai, hi, "woe, sorrow." Thus the words, "And it came to pass in those days of Amraphel, Arioch, Kenderlaomer, Tidal, Shemeber, Shinab, Backbrai, and Lama the kings of Shinar, Ellasar, Elam, Goiim, Zeboiim, Admah, Bela, and Lasha" in Genesis 14:1, are followed by the words, "they made war with Bera, Birsta, Nianhazel, and Melchizedek the kings of Sodom, Gomorrah, Zoar, and Salem" in Genesis 14:2. And the Gemara also cited the instances of Genesis 6:1 followed by Genesis 6:5; Genesis 11:2 followed by Genesis 11:4; Joshua 5:13 followed by the rest of Joshua 5:13; Joshua 6:27 followed by Joshua 7:1; 1 Samuel 1:1 followed by 1 Samuel 1:5; 1 Samuel 8:1 followed by 1 Samuel 8:3; 1 Samuel 18:14 close after 1 Samuel 18:9; 2 Samuel 7:1 followed by 1 Kings 8:19; Ruth 1:1 followed by the rest of Ruth 1:1; and Esther 1:1 followed by Haman. But the Gemara also cited as counterexamples the words, "And there was evening and there was morning one day," in Genesis 1:5, as well as Genesis 29:10, and 1 Kings 6:1. So Rav Ashi replied that wa-yehi sometimes presages misfortune, and sometimes it does not, but the expression "and it came to pass in the days of" always presages misfortune. And for that proposition, the Gemara cited Genesis 14:1, Isaiah 7:1 Jeremiah 1:3, Ruth 1:1, and Esther 1:1.[121]

Rav and Samuel equated the Amraphel of Genesis 14:1 with the Nimrod whom Genesis 10:8 describes as "a mighty warrior on the earth," but the two differed over which was his real name. One held that his name was actually Nimrod, and Genesis 14:1 calls him Amraphel because he ordered Abram to be cast into a burning furnace (and thus the name Amraphel reflects the words for "he said" (amar) and "he cast" (hipil)). But the other held that his name was actually Amraphel, and Genesis 10:8 calls him Nimrod because he led the world in rebellion against God (and thus the name Nimrod reflects the word for "he led in rebellion" (himrid)).[122]

Rabbi Berekiah and Rabbi Helbo taught in the name of Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman that the Valley of Siddim (mentioned in Genesis 14:3 in connection with the battle between the four kings and the five kings) was called the Valley of Shaveh (which means "as one") because there all the peoples of the world agreed as one, felled cedars, erected a large dais for Abraham, set him on top, and praised him, saying (in the words of Genesis 23:6, "Hear us, my lord: You are a prince of God among us." They told Abraham that he was king over them and a god to them. But Abraham replied that the world did not lack its King, and the world did not lack its God.[123]

A Midrash taught that there was not a mighty man in the world more difficult to overcome than Og, as Deuteronomy 3:11 says, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim." The Midrash told that Og had been the only survivor of the strong men whom Amraphel and his colleagues had slain, as may be inferred from Genesis 14:5, which reports that Amraphel "smote the Rephaim in Ashteroth-karnaim," and one may read Deuteronomy 3:1 to indicate that Og lived near Ashteroth. The Midrash taught that Og was the refuse among the Rephaim, like a hard olive that escapes being mashed in the olive press. The Midrash inferred this from Genesis 14:13, which reports that "there came one who had escaped, and told Abram the Hebrew," and the Midrash identified the man who had escaped as Og, as Deuteronomy 3:11 describes him as a remnant, saying, "only Og king of Bashan remained of the remnant of the Rephaim." The Midrash taught that Og intended that Abram should go out and be killed. God rewarded Og for delivering the message by allowing him to live all the years from Abraham to Moses, but God collected Og's debt to God for his evil intention toward Abraham by causing Og to fall by the hand of Abraham's descendants. On coming to make war with Og, Moses was afraid, thinking that he was only 120 years old, while Og was more than 500 years old, and if Og had not possessed some merit, he would not have lived all those years. So God told Moses (in the words of Numbers 21:34), "fear him not; for I have delivered him into your hand," implying that Moses should slay Og with his own hand.[124]

Rabbi Abbahu said in Rabbi Eleazar's name that "his trained men" in Genesis 14:14 meant Torah scholars, and thus when Abram made them fight to rescue Lot, he brought punishment on himself and his children, who were consequently enslaved in Egyptian for 210 years. But Samuel said that Abram was punished because he questioned whether God would keep God's promise, when in Genesis 15:8 Abram asked God "how shall I know that I shall inherit it?" And Rabbi Johanan said that Abram was punished because he prevented people from entering beneath the wings of the Shekhinah and being saved, when in Genesis 14:21 the king of Sodom said it to Abram, "Give me the persons, and take the goods yourself," and Abram consented to leave the prisoners with the king of Sodom. Rav interpreted the words "And he armed his trained servants, born in his own house" in Genesis 14:14 to mean that Abram equipped them by teaching them the Torah. Samuel read the word vayarek ("he armed") to mean "bright," and thus interpreted the words "And he armed his trained servants" in Genesis 14:14 to mean that Abram made them bright with gold, that is, rewarded them for accompanying him.[125]

Reading the report in Genesis 14:14 that Abram led 318 men, Rabbi Ammi bar Abba said that Abram's servant Eliezer outweighed them all. The Gemara reported that others (employing gematria) said that Eliezer alone accompanied Abram to rescue Lot, as the Hebrew letters in Eliezer's name have a numerical value of 318.[125]

Midrash identified the Melchizedek of Genesis 14:18 with Noah's son Shem.[126] The Rabbis taught that Melchizedek acted as a priest and handed down Adam's robes to Abraham.[127] Rabbi Zechariah said on Rabbi Ishmael's authority (or others say, it was taught at the school of Rabbi Ishmael) that God intended to continue the priesthood from Shem's descendants, as Genesis 14:18 says, "And he (Melchizedek/Shem) was the priest of the most high God." But then Melchizedek gave precedence in his blessing to Abram over God, and thus God decided to bring forth the priesthood from Abram. As Genesis 14:19 reports, "And he (Melchizedek/Shem) blessed him (Abram), and said: 'Blessed be Abram of God Most High, Maker of heaven and earth; and blessed be God the Most High, who has delivered your enemies into your hand.'" Abram replied to Melchizedek/Shem by questioning whether the blessing of a servant should be given precedence over that of the master. And straightaway, God gave the priesthood to Abram, as Psalm 110:1 says, "The Lord (God) said to my Lord (Abram), Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool," which is followed in Psalm 110:4 by, "The Lord has sworn, and will not repent, 'You (Abram) are a priest for ever, after the order (dibrati) of Melchizedek,'" meaning, "because of the word (dibbur) of Melchizedek." Hence Genesis 14:18 says, "And he (Melchizedek/Shem) was the priest of the most high God," implying that Melchizedek/Shem was a priest, but not his descendants.[128]

Rabbi Isaac the Babylonian said that Melchizedek was born circumcised.[129] A Midrash taught that Melchizedek called Jerusalem "Salem."[130] The Rabbis said that Melchizedek instructed Abraham in the Torah.[129] Rabbi Eleazar said that Melchizedek's school was one of three places where the Holy Spirit manifested itself.[131]

Rabbi Judah said in Rabbi Nehorai's name that Melchizedek's blessing yielded prosperity for Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.[132] Ephraim Miksha'ah the disciple of Rabbi Meir said in the latter's name that Tamar descended from Melchizedek.[133]

Rabbi Hana bar Bizna citing Rabbi Simeon Hasida (or others say Rabbi Berekiah in the name of Rabbi Isaac) identified Melchizedek as one of the four craftsmen of whom Zechariah wrote in Zechariah 2:3.[134] The Gemara taught that David wrote the Book of Psalms, including in it the work of the elders, including Melchizedek in Psalm 110.[135]

Genesis chapter 15

According to the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, Genesis 15 reports Abraham’s seventh trial. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that God was revealed to all the prophets in a vision, but to Abraham God was revealed in a revelation and a vision. Genesis 18:1 tells of the revelation when it says, “And the Lord appeared to him by the oaks of Mamre.” And Genesis 15:1 tells of the vision when it says, “After these things the word of the Lord came to Abram in a vision.” According to the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, God told Abraham not to fear, for God would shield Abraham against misfortunes everywhere that he would go, and would give him and his children a good reward, in this world and in the world to come, as Genesis 15:1 says, “Your exceeding great reward.”[136]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer identified Abraham's servant Eliezer introduced in Genesis 15:2 with the unnamed steward of Abraham's household in Genesis 24:2. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that when Abraham left Ur of the Chaldees, all the magnates of the kingdom gave him gifts, and Nimrod gave Abraham Nimrod's first-born son Eliezer as a perpetual slave. After Eliezer had dealt kindly with Isaac by securing Rebekah to be Isaac's wife, he set Eliezer free, and God gave Eliezer his reward in this world by raising him up to become a king — Og, king of Bashan.[137]

The Gemara expounded on the words, "And He brought him outside," in Genesis 15:5. The Gemara taught that Abram had told God that Abram had employed astrology to see his destiny and had seen that he was not fated to have children. God replied that Abram should go "outside" of his astrological thinking, for the stars do not determine Israel's fate.[138]

The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana taught that Sarah was one of seven barren women about whom Psalm 113:9 says (speaking of God), "He ... makes the barren woman to dwell in her house as a joyful mother of children." The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana also listed Rebekah, Rachel, Leah, Manoah's wife, Hannah, and Zion. The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana taught that the words of Psalm 113:9, "He ... makes the barren woman to dwell in her house," apply, to begin with, to Sarah, for Genesis 11:30 reports that "Sarai was barren." And the words of Psalm 113:9, "a joyful mother of children," apply to Sarah, as well, for Genesis 21:7 also reports that "Sarah gave children suck."[139]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that Abraham inherited both this world and the World to Come as a reward for his faith, as Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And he believed in the Lord."[140]

Resh Lakish taught that Providence punishes bodily those who unjustifiably suspect the innocent. In Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Moses said that the Israelites "will not believe me," but God knew that the Israelites would believe. God thus told Moses that the Israelites were believers and descendants of believers, while Moses would ultimately disbelieve. The Gemara explained that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". reports that "the people believed" and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". reports that the Israelites' ancestor Abram "believed in the Lord," while Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". reports that Moses "did not believe." Thus, Moses was smitten when in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". God turned his hand white as snow.[141]

Rabbi Jacob bar Aha said in the name of Rav Assi that Abraham asked God whether God would wipe out Abraham's descendants as God had destroyed the generation of the Flood. Rabbi Jacob bar Aha said in the name of Rav Assi that Abraham's question in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "O Lord God, how shall I know that I shall inherit it?" was part of a larger dialogue. Abraham asked God if Abraham's descendants should sin before God, would God do to them as God did to the generation of the Flood (in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) and the generation of the Dispersion (in Genesis in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".). God told Abraham that God would not. Abraham then asked God (as reported in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), "Let me know how I shall inherit it." God answered by instructing Abraham (as reported in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), "Take Me a heifer of three years old, and a she-goat of three years old" (which Abraham was to sacrifice to God). Abraham acknowledged to God that this means of atonement through sacrifice would hold good while a sacrificial shrine remained in being, but Abraham pressed God what would become of his descendants when the Temple would no longer exist. God replied that God had already long ago provided for Abraham's descendants in the Torah the order of the sacrifices, and whenever they read it, God would deem it as if they had offered them before God, and God would grant them pardon for all their iniquities. Rabbi Jacob bar Aha said in the name of Rav Assi that this demonstrated that were it not for the מעמדות, Ma'amadot, groups of lay Israelites who participated in worship as representatives of the public, then heaven and earth could not endure.[142]

Reading Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". “And he said: ‘O Lord God, whereby shall I know that I shall inherit it?’” Rabbi Hama bar Hanina taught that Abraham was not complaining, but asked God through what merit Abraham would inherit the land. God replied that Abraham and his descendants would merit the land through the atoning sacrifices that God would institute for Abraham’s descendants, as indicated by the next verse, in which God said, “Take Me a heifer of three years old . . . .”[143]

Reading Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". “And He said to him: ‘Take me a heifer of three years old (מְשֻׁלֶּשֶׁת, meshuleshet), a she-goat of three years old (מְשֻׁלֶּשֶׁת, meshuleshet), and a ram of three years old (מְשֻׁלָּשׁ, meshulash),’” a Midrash read מְשֻׁלֶּשֶׁת, meshuleshet, to mean “three-fold” or “three kinds,” indicating sacrifices for three different purposes. The Midrash deduced that God thus showed Abraham three kinds of bullocks, three kinds of goats, and three kinds of rams that Abraham’s descendants would need to sacrifice. The three kinds of bullocks were: (1) the bullock that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". would require the Israelites to sacrifice on the Day of Atonement (יוֹם כִּיפּוּר, Yom Kippur), (2) the bullock that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". would require the Israelites to bring on account of unwitting transgression of the law, and (3) the heifer whose neck Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". would require the Israelites to break. The three kinds of goats were: (1) the goats that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". would require the Israelites to sacrifice on festivals, (2) the goats that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". would require the Israelites to sacrifice on the New Moon (ראש חודש, Rosh Chodesh), and (3) the goat that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". would require an individual to bring. The three kinds of rams were: (1) the guilt-offering of certain obligation that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". for example, would require one who committed a trespass to bring, (2) the guilt-offering of doubt to which one would be liable when in doubt whether one had committed a transgression, and (3) the lamb to be brought by an individual. Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai said that God showed Abraham all the atoning sacrifices except for the tenth of an ephah of fine meal in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". The Rabbis said that God showed Abraham the tenth of an ephah as well, for Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says “all these (אֵלֶּה, eleh),” just as Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, “And you shall bring the meal-offering that is made of these things (מֵאֵלֶּה, me-eleh),” and the use of “these” in both verses hints that both verses refer to the same thing. And reading Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". “But the bird divided he not,” the Midrash deduced that God intimated to Abraham that the bird burnt-offering would be divided, but the bird sin-offering (which the dove and young pigeon symbolized) would not be divided.[144]

A Midrash noted the difference in wording between Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". which says of the Israelites in Goshen that "they got possessions therein," and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". which says of the Israelites in Canaan, "When you come into the land of Canaan, which I gave you for a possession." The Midrash read Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". to read, "and they were taken in possession by it." The Midrash thus taught that in the case of Goshen, the land seized the Israelites, so that their bond might be exacted and so as to bring about God's declaration to Abraham in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". that the Egyptians would afflict the Israelites for 400 years. But the Midrash read Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". to teach the Israelites that if they were worthy, the Land of Israel would be an eternal possession, but if not, they would be banished from it.[145]

The Mishnah pointed to God's announcement to Abram in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". that his descendants would return from Egyptian slavery to support the proposition that the merits of the father bring about benefits for future generations.[146]

A Midrash taught that Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". call the Euphrates "the Great River" because it encompasses the Land of Israel. The Midrash noted that at the creation of the world, the Euphrates was not designated "great." But it is called "great" because it encompasses the Land of Israel, which Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". calls a "great nation." As a popular saying said, the king's servant is a king, and thus Scripture calls the Euphrates great because of its association with the great nation of Israel.[147]

Genesis chapter 16

Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai deduced from the words, "and she had a handmaid, an Egyptian, whose name was Hagar," in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". that Hagar was Pharaoh's daughter. Rabbi Simeon taught that when Pharaoh saw what God did on Sarah's behalf, Pharaoh gave his daughter to Sarai, reasoning that it would be better for his daughter to be a handmaid in Sarai's house than a mistress in another house. Rabbi Simeon read the name "Hagar" in to mean "reward" (agar), imagining Pharaoh to say, "Here is your reward (agar)."[148]

A Midrash deduced from Sarai's words in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "Behold now, the Lord has restrained me from bearing; go into my handmaid; it may be that I shall be built up through her," that one who is childless is as one who is demolished. The Rabbi of the Midrash reasoned that only that which is demolished must be "built up."[149]

Rabbi Simeon wept that Hagar, the handmaid of Rabbi Simeon's ancestor Abraham's house, was found worthy of meeting an angel on three occasions (including in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), while Rabbi Simeon did not meet an angel even once.[150]

A Midrash found in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". support for the proverb that if a person tells you that you have a donkey's ears, do not believe it, but if two tell it to you, order a halter. For Abraham called Hagar Sarai's servant the first time in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". saying, "Behold, your maid is in your hand." And then the angel called Hagar Sarai's servant the second time in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". saying, "Hagar, Sarai's handmaid." Thus, thereafter in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Hagar acknowledged that she was Sarai's servant, saying, "I flee from the face of my mistress Sarai."[151] Similarly, Rava asked Rabbah bar Mari where Scripture supports the saying of the Rabbis that if your neighbor (justifiably) calls you a donkey, you should put a saddle on your back (and not quarrel to convince the neighbor otherwise). Rabbah bar Mari replied that the saying found support in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". where first the angel calls Hagar "Sarai's handmaid," and then Hagar acknowledged that she was Sarai's servant, saying, "I flee from the face of my mistress Sarai."[152]

Noting that the words "and an angel of the Lord said to her" occur three times in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". a Midrash asked how many angels visited Hagar. Rabbi Hama bar Rabbi Hanina said that five angels visited her, for each time the text mentions "speech," it refers to an angel. The Rabbis said that four angels visited her, as the word "angel" occurs 4 times. Rabbi Hiyya taught that Hagar's encounter with the angels showed how great the difference was between the generations of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs and later generations. Rabbi Hiyya noted that after Judges Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". reports that Manoah and his wife, the parents of Samson, saw an angel, Manoah exclaimed to his wife in fear (in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), "We shall surely die, because we have seen God." Yet Hagar, a bondmaid, saw five angels and was not afraid. Rabbi Aha taught that a fingernail of the Patriarchs was more valuable than the abdomen of their descendants. Rabbi Isaac interpreted Proverbs Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "She sees the ways of her household," to apply homiletically to teach that all who lived in Abraham's household were seers, so Hagar was accustomed to seeing angels.[151]

Rabbi Simeon wept when he thought that Hagar, the handmaid of Rabbi Simeon's ancestor Sarah, was found worthy of meeting an angel three times (including in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), while Rabbi Simeon did not meet an angel even once.[150]

A Midrash counted Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". in which the angel told Hagar, "Behold, you are with child ... and you shall call his name Ishmael," among four instances in which Scripture identifies a person's name before birth. Rabbi Isaac also counted the cases of Isaac (in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), Solomon (in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), and Josiah (in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".).[153]

The Gemara taught that if one sees Ishmael in a dream, then God hears that person's prayer (perhaps because the name "Ishmael" derives from "the Lord has heard" in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". or perhaps because "God heard" (yishmah Elohim, יִּשְׁמַע אֱלֹהִים) Ishmael's voice in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".).[154]

Genesis chapter 17

Resh Lakish taught that the words "I am God Almighty (אֵל שַׁדַּי, El Shaddai)" in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". mean, "I am He Who said to the world: 'Enough! (דַּי, Dai).'" Resh Lakish taught that when God created the sea, it went on expanding, until God rebuked it and caused it to dry up, as Nahum Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "He rebukes the sea and makes it dry, and dries up all the rivers."[155]

Rabbi Judah contrasted God's words to Abraham, "walk before Me," in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". with the words, "Noah walked with God," in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Rabbi Judah compared it to a king who had two sons, one grown up and the other a child. The king asked the child to walk with him. But the king asked the adult to walk before him. Similarly, to Abraham, whose moral strength was great, God said, "Walk before Me." But of Noah, who was feeble, Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "Noah walked with God." Rabbi Nehemiah compared Noah to a king's friend who was plunging about in dark alleys, and when the king saw him sinking in the mud, the king urged his friend to walk with him instead of plunging about. Abraham's case, however, was compared to that of a king who was sinking in dark alleys, and when his friend saw him, the friend shined a light for him through the window. The king then asked his friend to come and shine a light before the king on his way. Thus, God told Abraham that instead of showing a light for God from Mesopotamia, he should come and show one before God in the Land of Israel. Similarly, Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And he blessed Joseph, and said: The God before whom my fathers Abraham and Isaac did walk . ... " Rabbi Berekiah in Rabbi Johanan's name and Resh Lakish gave two illustrations of this. Rabbi Johanan said: It was as if a shepherd stood and watched his flocks. (Similarly, Abraham and Isaac walked before God and under God's protection.) Resh Lakish said: It was as if a prince walked along while the elders preceded him (as an escort, to make known his coming). (Similarly, Abraham and Isaac walked before God, spreading word of God.) The Midrash taught that in Rabbi Johanan's view: We need God's proximity, while in Resh Lakish's view, God needs us to glorify God (by propagating the knowledge of God's greatness).[156] Similarly, a Midrash read the words "Noah walked with God" in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". to mean that God supported Noah, so that Noah should not be overwhelmed by the evil behavior of the generation of the Flood. The Midrash compared this to a king whose son went on a mission for his father. The road ahead of him was sunken in mire, and the king supported him so that he would not sink in the mire. However, in the case of Abraham, God said in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "walk before Me," and regarding the Patriarchs, Jacob said in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "The God before whom my fathers Abraham and Isaac walked." For the Patriarchs would try to anticipate the Divine Presence, and would go ahead to do God's will.[157]

Rabbi taught that notwithstanding all the precepts that Abram fulfilled, God did not call him "perfect" until he circumcised himself, for in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". God told Abram, "Walk before me and be perfect. And I will make my covenant between me and you," and in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". God explained that God's covenant required that every male be circumcised.[158]

Rav Judah said in Rav's name that when God told Abram in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "Walk before me and be perfect," Abram was seized with trembling, thinking that perhaps there was some shameful flaw in him that needed correcting. But when God added in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "And I will make My covenant between me and you," God set Abram's mind at ease. Rabbi Hoshaiah taught that if one perfects oneself, then good fortune will follow, for Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "Walk before me and be perfect," and shortly thereafter Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". reports Abram's reward for doing so: "And you shall be a father of many nations."[159]

Rabbi Ammi bar Abba employed gematria to interpret the meaning of Abram's name change in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". from Abram (אַבְרָם) to Abraham (אַבְרָהָם). According to Rabbi Ammi bar Abba, at first God gave Abram mastery over 243 of his body parts, as the numerical value of the Hebrew letters in Abram is 243. Then God gave Abraham mastery over 248 of his body parts, adding five body parts, as the numerical value of the Hebrew letter hei (ה) that God added to his name is five. The Gemara explained that as a reward for Abraham's undergoing circumcision, God granted Abraham control over his two eyes, his two ears, and the organ that he circumcised.[160]

The Mishnah notes that transgressing the command of circumcision in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". is one of 36 transgressions that cause the transgressor to be cut off from his people.[161]

The Gemara read the command of Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". to require an uncircumcised adult man to become circumcised, and the Gemara read the command of Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". to require the father to circumcise his infant child.[162]

Rav Zeira counted five kinds of orlah (things uncircumcised) in the world: (1) uncircumcised ears (as in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), (2) uncircumcised lips (as in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), (3) uncircumcised hearts (as in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), (4) uncircumcised flesh (as in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".), and (5) uncircumcised trees (as in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".). Rav Zeira taught that all the nations are uncircumcised in each of the first four ways, and all the house of Israel are uncircumcised in heart, in that their hearts do not allow them to do God's will. And Rav Zeira taught that in the future, God will take away from Israel the uncircumcision of their hearts, and they will not harden their stubborn hearts anymore before their Creator, as Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And I will take away the stony heart out of your flesh, and I will give you an heart of flesh," and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And you shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskin."[163]

Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina taught that visiting those who have had medical procedures (as Abraham had in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) demonstrates one of God's attributes that humans should emulate. Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina asked what Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". means in the text, "You shall walk after the Lord your God." How can a human being walk after God, when Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "[T]he Lord your God is a devouring fire"? Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina explained that the command to walk after God means to walk after the attributes of God. As God clothes the naked — for Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife coats of skin, and clothed them" — so should we also clothe the naked. God visited the sick — for Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And the Lord appeared to him by the oaks of Mamre" (after Abraham was circumcised in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) — so should we also visit the sick. God comforted mourners — for Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And it came to pass after the death of Abraham, that God blessed Isaac his son" — so should we also comfort mourners. God buried the dead — for Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "And He buried him in the valley" — so should we also bury the dead.[164] Similarly, the Sifre on Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". taught that to walk in God's ways means to be (in the words of Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) "merciful and gracious."[165]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[166]

Genesis chapters 11–22

In their commentaries to Mishnah Avot 5:3[79] (see "In classical rabbinic interpretation" above), Rashi and Maimonides differed on what 10 trials Abraham faced:[167]

| Rashi | Maimonides | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abraham hid underground for 13 years from King Nimrod, who wanted to kill him. | ||

| 2 | Nimrod threw Abraham into a fiery furnace. | ||

| 3 | God commanded Abraham to leave his family and homeland. | 1 | Abraham's exile from his family and homeland |

| 4 | As soon as he arrived in the Promised Land, Abraham was forced to leave to escape a famine. | 2 | The famine in the Promised Land after God assured Abraham that he would become a great nation there |

| 5 | Pharaoh's officials kidnapped Sarah. | 3 | The corruption in Egypt that resulted in the kidnapping of Sarah |

| 6 | Kings captured Lot, and Abraham had to rescue him. | 4 | The war with the four kings |

| 7 | God told Abraham that his descendants would suffer under four regimes. | ||

| 5 | Abraham's marriage to Hagar after having despaired that Sarah would ever give birth | ||

| 8 | God commanded Abraham to circumcise himself and his son when Abraham was 99 years old. | 6 | The commandment of circumcision |

| 7 | Abimelech's abduction of Sarah | ||

| 9 | Abraham was commanded to drive away Ishmael and Hagar. | 8 | Driving away Hagar after she had given birth |

| 9 | The very distasteful command to drive away Ishmael | ||

| 10 | God commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac. | 10 | The binding of Isaac on the altar |

Genesis chapter 13

In his letter to Obadiah the Proselyte, Maimonides relied on Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". to addressed whether a convert could recite declarations like "God of our fathers." Maimonides wrote that converts may say such declarations in the prescribed order and not change them in the least, and may bless and pray in the same way as every Jew by birth. Maimonides reasoned that Abraham taught the people, brought many under the wings of the Divine Presence, and ordered members of his household after him to keep God's ways forever. As God said of Abraham in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "I have known him to the end that he may command his children and his household after him, that they may keep the way of the Lord, to do righteousness and justice." Ever since then, Maimonides taught, whoever adopts Judaism is counted among the disciples of Abraham. They are Abraham's household, and Abraham converted them to righteousness. In the same way that Abraham converted his contemporaries, he converts future generations through the testament that he left behind him. Thus Abraham is the father of his posterity who keep his ways and of all proselytes who adopt Judaism. Therefore, Maimonides counseled converts to pray, "God of our fathers," because Abraham is their father. They should pray, "You who have taken for his own our fathers," for God gave the land to Abraham when in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". God said, "Arise, walk through the land in the length of it and in the breadth of it; for I will give to you." Maimonides concluded that there is no difference between converts and born Jews. Both should say the blessing, "Who has chosen us," "Who has given us," "Who have taken us for Your own," and "Who has separated us"; for God has chosen converts and separated them from the nations and given them the Torah. For the Torah has been given to born Jews and proselytes alike, as Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". says, "One ordinance shall be both for you of the congregation, and also for the stranger that sojourns with you, an ordinance forever in your generations; as you are, so shall the stranger be before the Lord." Maimonides counseled converts not to consider their origin as inferior. While born Jews descend from Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, converts derive from God, through whose word the world was created. As Isaiah said in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". "One shall say, I am the Lord's, and another shall call himself by the name of Jacob."[168]

Genesis chapter 15