Neuroscience of religion

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 15 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 15 min

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Influences |

| Research |

The neuroscience of religion, also known as "neurotheology"[1] or "spiritual neuroscience,"[2] seeks to explain the biological and neurological processes behind religious experience.[3] Researchers in this field study correlations of the biological neural phenomena, in addition to subjective experiences of spirituality, in order to explain how brain activity functions in response to religious and spiritual practices and beliefs. This contrasts with the psychology of religion, which studies the behavioral responses to religious practices. Some people do warn of the limitations of neurotheology, as they worry that it may simplify the socio-cultural complexity of religion down to neurological factors.

Researchers that study the field of the neuroscience of religion use a formulation of scientific techniques to understand the correlations between brain pathways in response to spiritually based stimuli. The is used interdisciplinary with neurological and evolutionary studies in order to understand the broader subjective experiences under which traditionally categorized spiritual or religious practices are organized.[4] This is done through a multilateral approach of scientific and cultural studies. Such studies include but is not limited to fMRI and EEG scans, theological studies, and anthropological studies. By using these approaches, researchers can better understand how spirituality and religion affect the chemistry of human brains and in turn how brain activity may affect experiences of transcendence and spirituality.

Terminology

Neurotheology

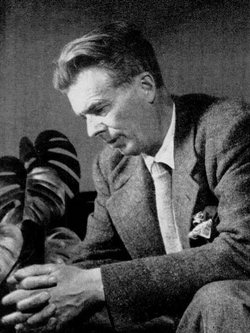

Aldous Huxley coined the term "neurotheology" for the first time[citation needed] in his utopian novel Island.[5] In this, he described the discipline as a combination of cognitive neuroscience of religious experience and spirituality. The term has also been used in a less scientific context, but rather as a subcategory of philosophy. In some cases, according to the mainstream scientific community, this is considered as a pseudoscience.

Biocultural

In Armin W. Geertz article on Brain, Body and Culture: A Biocultural Theory of Religion, the term "biocultural" refers to the simultaneous intersection of humans as both biological and cultural animals.[6] In his article, Geertz discusses the connection between the human brain and the rest of the body, stating that the brain does not work independently, but rather in unison with other sense organs in the body. Essentially, arguing that the "cognition functions in the embodiment of the brain."[7] With this, he says that religio-spiritual practices (such as dancing, chanting, or the use of psychoactive substances) that engage the other senses, have physical effects on brain chemistry. This varies cross-culturally, as different cultural and religious practices engage in different methods to induce senses divine transcendence. This, in turn, demonstrates the connection between biology and cultural contexts, since neither are uniform.

Religion

Spiritual practices and religious rituals have been around for hundreds of thousands of years with some dating as far back as 300,000 in the Rising Star Cave with the discovery of Homo Naledi. Dave Vliegenthart's article Can Neurotheology Explain Religion? aims at answering the question of neurotheology as a legitimate way of explaining religious experiences. In this he defines the term "religion" as a "state of consciousness in which reality is deemed religious and thought and experienced through the lens of a particular human mind-set."[8] This is categorized under feelings of intuition, higher or altered states of consciousness, or a connection to a divine being. Through attempts to achieve religious ecstasy, people have tried to connect to divine or ethereal beings as a way to breed human connection in addition to achieving higher wisdom. This goal of attaining eternal knowledge or harmony with the universe is demonstrated cross culturally, as mentioned above in Geertz's work on biocultural studies.

Consciousness

According to an article in Scientific American, "consciousness" is everything a person experiences: a personal sense of reality based on experiences of one's own real life events.[9] The article discusses how neuronal correlates of consciousness and the neurological process that go behind the brain's formations of conscious thinking, saying how the senses relay information through the spinal cord to the cerebellum in order to translate physical experience into neurological interpretation.[9] For hundreds of thousands of years humans have been trying to find ways to alter their states of consciousness. This varies widely across cultural groups, religious practices, and more so when looking from individual to individual. In Ancient Greece, maenads would attempt this by ecstatic and frenzied dance. In Sufi Mysticism, also known as Rumism, there is a similar practice of the whirling dervishes where spinning in circles to music is done in order to create a connection with the define. In some more extreme cases, may include forms of asceticism such as fasting, celibacy, or extreme isolation.

History, Developments, and Theoretical Work

In an attempt to focus and clarify what was a growing interest in this field, 1994 educator and businessman Laurence O. McKinney published the first book on the subject, titled Neurotheology: Virtual Religion in the 21st Century. In addition to being written for a popular audience, it also promoted in the theological journal Zygon.[10] According to McKinney, "neurotheology" sources the basis of religious inquiry in relatively recent developmental neurophysiology. McKinney's theory emphasizes how pre-frontal development in humans creates an illusion of chronological time as a fundamental part of normal adult cognition past the age of three. The inability of the adult brain to retrieve earlier images experienced by an infantile brain creates questions such as "Where did I come from?" and "Where does it all go?" He suggests that this neurological process led to the creation of various religious explanations. Moreover, studies behind the experience of death as a peaceful regression into timelessness as the brain dies won praise from readers as varied as writer Arthur C. Clarke, eminent theologian Harvey Cox, and the Dalai Lama and sparked a new interest in the field. Similarly, radical Catholic theologian Eugen Drewermann developed a two-volume critique of traditional conceptions of God and the soul in which he reinterpreted religion based on contemporary neuroscientific research.[11] The neuroscientist Andrew B. Newberg has claimed that "intensely focused spiritual contemplation triggers an alteration in the activity of the brain that leads one to perceive transcendent religious experiences as solid, tangible reality. In other words, the sensation that Buddhists call oneness with the universe."[12] The orientation area requires sensory input to do its calculus. "If you block sensory inputs to this region, as you do during the intense concentration of meditation, you prevent the brain from forming the distinction between self and not-self," says Newberg. With no information from the senses arriving, the left orientation area cannot find any boundary between the self and the world. As a result, the brain seems to have no choice but "to perceive the self as endless and intimately interwoven with everyone and everything." "The right orientation area, equally bereft of sensory data, defaults to a feeling of infinite space. The meditators feel that they have touched infinity."[13] Still, it has also been argued "that neurotheology should be conceived and practiced within a theological framework."[14]

Experimental Work

In 1969, British biologist Alister Hardy founded a Religious Experience Research Centre (RERC) at Oxford after retiring from his post as Linacre Professor of Zoology. Citing William James's The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), he set out to collect first-hand accounts of numinous experiences. He was awarded the Templeton Prize before his death in 1985. His successor David Hay suggested in God's Biologist: A Life of Alister Hardy (2011) that the RERC later dispersed as investigators turned to newer techniques of scientific investigation.

Magnetic Stimulation Studies

During the 1980s Michael Persinger stimulated the temporal lobes of human subjects with a weak magnetic field using an apparatus that popularly became known as the "God helmet"[15] and reported that many of his subjects claimed to experience a "sensed presence" during stimulation.[16] This work has been criticised,[3][17] [18][19] though some researchers[20] have published a replication of one God Helmet experiment.[21]

Granqvist et al. claimed that Persinger's work was not double-blind. Participants were often graduate students who knew what sort of results to expect, and there was the risk that the experimenters' expectations would be transmitted to subjects by unconscious cues. The participants were frequently given an idea of the purpose of the study by being asked to fill in questionnaires designed to test their suggestibility to paranormal experiences before the trials were conducted. Granqvist et al. failed to replicate Persinger's experiments double-blinded, and concluded that the presence or absence of the magnetic field had no relationship with any religious or spiritual experience reported by the participants, but was predicted entirely by their suggestibility and personality traits. Following the publication of this study, Persinger et al. dispute this.[22] One published attempt to create a "haunted room" using environmental "complex" electromagnetic fields based on Persinger's theoretical and experimental work did not produce the sensation of a "sensed presence" and found that reports of unusual experiences were uncorrelated with the presence or absence of these fields. As in the study by Granqvist et al., reports of unusual experiences were instead predicted by the personality characteristics and suggestibility of participants.[23] One experiment with a commercial version of the God helmet found no difference in response to graphic images whether the device was on or off.[24][25]

Neuropsychology and Neuroimaging

The first researcher to note and catalog the abnormal experiences associated with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) was neurologist Norman Geschwind, who noted a set of religious behavioral traits associated with TLE seizures.[26] These include hypergraphia, hyperreligiosity, reduced sexual interest, fainting spells, and pedantism, often collectively ascribed to a condition known as Geschwind syndrome.

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran explored the neural basis of the hyperreligiosity seen in TLE using the galvanic skin response (GSR), which correlates with emotional arousal, to determine whether the hyperreligiosity seen in TLE was due to an overall heightened emotional state or was specific to religious stimuli. Ramachandran presented two subjects with neutral, sexually arousing and religious words while measuring GSR. Ramachandran was able to show that patients with TLE showed enhanced emotional responses to the religious words, diminished responses to the sexually charged words, and normal responses to the neutral words. This study was presented as an abstract at a neuroscience conference and referenced in Ramachandran's book, Phantoms in the Brain,[27] which was not published as a peer-reviewed scientific article.

Research by Mario Beauregard at the University of Montreal, using fMRI on Carmelite nuns, has purported to show that religious and spiritual experiences include several brain regions and not a single 'God spot'. As Beauregard has said, "There is no God spot in the brain. Spiritual experiences are complex, like intense experiences with other human beings."[28] The neuroimaging was conducted when the nuns were asked to recall past mystical states, not while actually undergoing them; "subjects were asked to remember and relive (eyes closed) the most intense mystical experience ever felt in their lives as a member of the Carmelite Order."[29] A 2011 study by researchers at the Duke University Medical Center found hippocampal atrophy is associated with older adults who report life-changing religious experiences, as well as those who are "born-again Protestants, Catholics, and those with no religious affiliation".[30]

A 2016 study using fMRI found "a recognizable feeling central to ... (Mormon)... devotional practice was reproducibly associated with activation in nucleus accumbens, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and frontal attentional regions. Nucleus accumbens activation preceded peak spiritual feelings by 1–3 s and was replicated in four separate tasks. ... The association of abstract ideas and brain reward circuitry may interact with frontal attentional and emotive salience processing, suggesting a mechanism whereby doctrinal concepts may come to be intrinsically rewarding and motivate behavior in religious individuals."[31]

Psychopharmacology

Some scientists working in the field hypothesize that the basis of spiritual experience arises in neurological physiology. Speculative suggestions have been made that an increase of N,N-dimethyltryptamine levels in the pineal gland contribute to spiritual experiences.[32][33] It has also been suggested that stimulation of the temporal lobe by psychoactive ingredients of magic mushrooms mimics religious experiences.[34] This hypothesis has found laboratory validation with respect to psilocybin.[35][36]

See also

- Bicameral mentality

- Cognitive science of religion

- Psychedelic crisis

- Religion and schizophrenia

- Scholarly approaches to mysticism

- Transpersonal psychology

References

- ↑ "Neurotheology: This Is Your Brain On Religion". NPR. 15 December 2010. https://www.npr.org/2010/12/15/132078267/neurotheology-where-religion-and-science-collide.

- ↑ Biello, David (October 2007). "Searching for God in the Brain". Scientific American 18 (5): 38–45. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind1007-38.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Aaen-Stockdale, Craig (2012). "Neuroscience for the Soul". The Psychologist 25 (7): 520–523. http://www.thepsychologist.org.uk/archive/archive_home.cfm?volumeID=25&editionID=215&ArticleID=2097. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ↑ Gajilan, A. Chris (2007-04-05). "Are humans hard-wired for faith?". http://cnn.health.printthis.clickability.com/pt/cpt?action=cpt&title=Are+humans+hard-wired+for+faith%3F+-+CNN.com&expire=&urlID=21822630&fb=Y&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.cnn.com%2F2007%2FHEALTH%2F04%2F04%2Fneurotheology%2Findex.html&partnerID=2012. "[...] these brain scans may provide proof that our brains are built to believe in God. He says there may be universal features of the human mind that actually make it easier for us to believe in a higher power. [...] Anthropologists like Atran say, 'Religion is a byproduct of many different evolutionary functions that organized our brains for day-to-day activity.'"

- ↑ Huxley, Aldous. Island: A Novel. Bantam, 1963.

- ↑ Geertz, Armin W. "Brain, Body and Culture: A Biocultural Theory of Religion." Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 22, no. 4, 2010, pp. 304–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23555751. Accessed 16 May 2025.

- ↑ Geertz, Armin W. "Brain, Body and Culture: A Biocultural Theory of Religion." Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 22, no. 4, 2010, pp. 304–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23555751. Accessed 16 May 2025.

- ↑ Vliegenthart, Dave. "Can Neurotheology Explain Religion?" Archiv Für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion 33, no. 2 (2011): 137–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23919331

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Koch, Christof (2018-06-01). "What Is Consciousness?" (in en). https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-consciousness/.

- ↑ McKinney, Laurence O. (1994). Neurotheology: Virtual Religion in the 21st Century. American Institute for Mindfulness. ISBN 978-0-945724-01-8.

- ↑ Drewermann, Eugen (2006–2007) (in de). Atem des Lebens: Die moderne Neurologie und die Frage nach Gott. (Modern neurology and the question of God) Vol 1: Das Gehirn. Vol. 2: Die Seele.. Düsseldorf: Patmos Verlag. pp. Vol. 1: 864; Vol. 2: 1072. (Vol. 1). (Vol. 2). ISBN 978-3-491-21000-4. http://www.freewebs.com/drewermann-eugen/booksbcher.htm.

- ↑ Newberg, Andrew B.; D'Aquili, Eugene G.; Rause, Vince (2002). Why God Won't Go Away. Brain Science and the Biology of Belief. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-44034-1.

- ↑ Begley, Sharon (6 May 2001). "Religion and the Brain". Newsweek (New York City: Newsweek Media Group). http://www.newsweek.com/religion-and-brain-152895.

- ↑ Apfalter, Wilfried (May 2009). "Neurotheology: What Can We Expect from a (Future) Catholic Version?". Theology and Science 7 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1080/14746700902796528.

- ↑ Persinger, M A (1983). "Religious and mystical experiences as artifacts of temporal lobe function: a general hypothesis.". Perceptual and Motor Skills 57 (3 Pt 2): 1255–62. doi:10.2466/pms.1983.57.3f.1255. PMID 6664802.

- ↑ Persinger, M. A. (2003). "The Sensed Presence Within Experimental Settings: Implications for the Male and Female Concept of Self". The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 137 (1): 5–16. doi:10.1080/00223980309600595. PMID 12661700.

- ↑ Granqvist, P; Fredrikson, M; Unge, P; Hagenfeldt, A; Valind, S; Larhammar, D; Larsson, M (2005). "Sensed presence and mystical experiences are predicted by suggestibility, not by the application of transcranial weak complex magnetic fields". Neuroscience Letters 379 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.057. PMID 15849873.

- ↑ Khamsi, Roxanne (9 December 2004). "Electrical brainstorms busted as source of ghosts". BioEd Online. http://www.bioedonline.org/news/news.cfm?art=1424.

- ↑ Larsson, M.; Larhammarb, D.; Fredrikson, M.; Granqvist, P. (2005). "Reply to M.A. Persinger and S. A. Koren's response to Granqvist et al. "Sensed presence and mystical experiences are predicted by suggestibility, not by the application of transcranial weak magnetic fields"". Neuroscience Letters 380 (3): 348–350. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.059.

- ↑ Tinoca, Carlos A; Ortiz, João PL (2014). "Magnetic Stimulation of the Temporal Cortex: A Partial "God Helmet" Replication Study". Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research 5 (3): 234–257.

- ↑ Richards, P M; Persinger, M A; Koren, S A (1993). "Modification of activation and evaluation properties of narratives by weak complex magnetic field patterns that simulate limbic burst firing.". The International Journal of Neuroscience 71 (1–4): 71–85. doi:10.3109/00207459309000594. PMID 8407157.

- ↑ Persinger, Michael (2005). "A response to Granqvist et al. 'Sensed presence and mystical experiences are predicted by suggestibility, not by the application of transcranial weak magnetic fields'". Neuroscience Letters 380 (1): 346–347. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.060. PMID 15862915.

- ↑ French, C. C.; Haque, U.; Bunton-Stasyshyn, R.; Davis, R. (2009). "The "Haunt" project: An attempt to build a "haunted" room by manipulating complex electromagnetic fields and infrasound". Cortex 45 (5): 619–629. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2007.10.011. PMID 18635163. http://research.gold.ac.uk/4209/2/French_et_al_Haunt_accepted.pdf.

- ↑ Gendle, M. H.; McGrath, M. G. (2012). "Can the 8-coil shakti alter subjective emotional experience? A randomized, placebo-controlled study.". Perceptual and Motor Skills 114 (1): 217–235. doi:10.2466/02.24.pms.114.1.217-235. PMID 22582690.

- ↑ Aaen-Stockdale, Craig (2012). "Neuroscience for the Soul". The Psychologist 25 (7): 520–523. http://www.thepsychologist.org.uk/archive/archive_home.cfm?volumeID=25&editionID=215&ArticleID=2097. Retrieved 6 July 2012. "Murphy claims his devices are able to modulate emotional states in addition to enhancing meditation and generating altered states. In flat contradiction of this claim, Gendle & McGrath (2012) found no significant difference in emotional state whether the device was on or off.".

- ↑ Waxman, S. G.; Geschwind, N. (1975). "The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy". Arch Gen Psychiatry 32 (12): 1580–6. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760300118011. PMID 1200777.

- ↑ Ramachandran, V. (1998). Phantoms in the Brain. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-688-15247-5.

- ↑ Harper Collins Publishers Author Interview with mario Beauregard, HarperCollins.com, http://www.harpercollins.com/author/authorExtra.aspx?authorID=30251&displayType=interview, retrieved 21 August 2011

- ↑ Beauregard, Mario (25 September 2006). "Neural correlates of a mystical experience in Carmelite nuns". Neuroscience Letters 405 (3): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.060. PMID 16872743.

- ↑ Owen, A. D.; Hayward, R. D.; Koenig, H. G.; Steffens, D. C.; Payne, M. E. (2011). "Religious factors and hippocampal atrophy in late life". PLOS ONE 6 (3). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017006. PMID 21479219. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...617006O.

- ↑ Ferguson, M. A. et al. (2018). "Reward, salience, and attentional networks are activated by religious experience in devout Mormons.". Social Neuroscience 13 (1): 104–116. doi:10.1080/17470919.2016.1257437. PMID 27834117. PMC 5478470. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:35015066.

- ↑ Strassman, R. (2001). DMT: The Spiritual Molecule. Inner Traditions Bear and Company. ISBN 978-0-89281-927-0. https://archive.org/details/dmtspiritmolecul00rick.

- ↑ Hood, Ralph W. and Jacob A. Belzen Jr. (2005). "Research Methods in the Psychology of Religion", in Handbook of the Psychology of Religion And Spirituality, ed. by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-57230-922-7.

- ↑ Skatssoon, Judy (2006-07-12). "Magic mushrooms hit the God spot". ABC Science Online. http://www.abc.net.au/science/news/health/HealthRepublish_1682610.htm.

- ↑ Griffiths, Rr; Richards, Wa; Johnson, Mw; McCann, Ud; Jesse, R (2008). "Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later.". Journal of Psychopharmacology 22 (6): 621–32. doi:10.1177/0269881108094300. PMID 18593735.

- ↑ Griffiths, R R; Richards, W A; McCann, U; Jesse, R (2006). "Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance.". Psychopharmacology 187 (3): 268–83; discussion 284–92. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5. PMID 16826400.

Further reading

- Begley, Sharon (7 May 2001). "Your Brain on Religion: Mystic visions or brain circuits at work?". Newsweek. http://www.cognitiveliberty.org/neuro/neuronewswk.htm.

- Hitt, Jack (1 November 1999). "This Is Your Brain on God". Wired. https://www.wired.com/wired/archive/7.11/persinger.html.

- Neher, Andrew (1990). The Psychology of Transcendence (2nd ed.). Dover. ISBN 0-486-26167-0.

- Newberg, Andrew B. (1999). The Mystical Mind: Probing the Biology of Religious Experience. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-3163-3.

- McNamara, Patrick (2009). The Neuroscience of Religious Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88958-2.

- Powell, Victoria (2007). "Neurotheology: With God in Mind". http://www.clinicallypsyched.com/neurotheologywithgodinmind.htm.

- Roberts, Thomas B. (2006). "Chemical Input — Religious Output: Entheogens". in McNamara, Robert. Where God and Science Meet: The Psychology of Religious Experience. 3. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-98791-6.

- Runehov, Anne L. C. (2007). Sacred or Neural? The Potential of Neuroscience to Explain Religious Experience. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-56980-1.

- Vliegenthart, Dave. "Can Neurotheology Explain Religion?" Archiv Für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion 33, no. 2 (2011): 137–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23919331.

- Geertz, Armin W. "Brain, Body and Culture: A Biocultural Theory of Religion." Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 22, no. 4, 2010, pp. 304–21. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23555751.

- Taylor, Jill Bolte. "My Stroke of Insight." TED Talks, 2019.

- Carvour HM, Radke AK and French NS (2025): A review of the neuroscience of religion: an overview of the field, its limitations, and future interventions. Front. Neurosci. 19:1587794. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2025.1587794.

External links

|

KSF

KSF