Priest

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities. Their office or position is the "priesthood", a term which also may apply to such persons collectively. A priest may have the duty to hear confessions periodically, give marriage counseling, provide prenuptial counseling, give spiritual direction, teach catechism, or visit those confined indoors, such as the sick in hospitals and nursing homes.

Description

According to the trifunctional hypothesis of prehistoric Proto-Indo-European society, priests have existed since the earliest of times and in the simplest societies, most likely as a result of agricultural surplus and consequent social stratification.[1] The necessity to read sacred texts and keep temple or church records helped foster literacy in many early societies. Priests exist in many religions today, such as all or some branches of Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Shinto, and Hinduism. They are generally regarded as having privileged contact with the deity or deities of the religion to which they subscribe, often interpreting the meaning of events and performing the rituals of the religion. There is no common definition of the duties of priesthood between faiths; but generally it includes mediating the relationship between one's congregation, worshippers, and other members of the religious body, and its deity or deities, and administering religious rituals and rites. These often include blessing worshipers with prayers of joy at marriages, after a birth, and at consecrations, teaching the wisdom and dogma of the faith at any regular worship service, and mediating and easing the experience of grief and death at funerals – maintaining a spiritual connection to the afterlife in faiths where such a concept exists. Administering religious building grounds and office affairs and papers, including any religious library or collection of sacred texts, is also commonly a responsibility – for example, the modern term for clerical duties in a secular office refers originally to the duties of a cleric. The question of which religions have a "priest" depends on how the titles of leaders are used or translated into English. In some cases, leaders are more like those that other believers will often turn to for advice on spiritual matters, and less of a "person authorized to perform the sacred rituals." For example, clergy in Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy are priests, as with certain synods of Lutheranism and Anglicanism, though other branches of Protestant Christianity, such as Methodists and Baptists, use minister and pastor. The terms priest and priestess are sufficiently generic that they may be used in an anthropological sense to describe the religious mediators of an unknown or otherwise unspecified religion.

In many religions, being a priest or priestess is a full-time position, ruling out any other career. Many Christian priests and pastors choose or are mandated to dedicate themselves to their churches and receive their living directly from their churches. In other cases, it is a part-time role. For example, in the early history of Iceland the chieftains were titled goði, a word meaning "priest". As seen in the saga of Hrafnkell Freysgoði, however, being a priest consisted merely of offering periodic sacrifices to the Norse gods and goddesses; it was not a full-time role, nor did it involve ordination.

In some religions, being a priest or priestess is by human election or human choice. In Judaism, the priesthood is inherited in familial lines. In a theocracy, a society is governed by its priesthood.

Etymology

The word "priest", is ultimately derived from Latin via Greek presbyter,[2] the term for "elder", especially elders of Jewish or Christian communities in late antiquity. The Latin presbyter ultimately represents Greek πρεσβύτερος presbúteros, the regular Latin word for "priest" being sacerdos, corresponding to ἱερεύς hiereús.

It is possible that the Latin word was loaned into Old English, and only from Old English reached other Germanic languages via the Anglo-Saxon mission to the continent, giving Old Icelandic prestr, Old Swedish präster, Old High German priast. Old High German also has the disyllabic priester, priestar, apparently derived from Latin independently via Old French presbtre.

An alternative theory makes priest cognate with Old High German priast, prest, from Vulgar Latin *prevost "one put over others", from Latin praepositus "person placed in charge".[3]

That English should have only the single term priest to translate presbyter and sacerdos came to be seen as a problem in English Bible translations. The presbyter is the minister who both presides and instructs a Christian congregation, while the sacerdos, offerer of sacrifices, or in a Christian context the eucharist, performs "mediatorial offices between God and man".[4]

The feminine English noun, priestess, was coined in the 17th century, to refer to female priests of the pre-Christian religions of classical antiquity. In the 20th century, the word was used in controversies surrounding the women ordained in the Anglican communion, who are referred to as "priests", irrespective of gender, and the term priestess is generally considered archaic in Christianity.

Webster's 1829 Dictionary stated "PRIEST, noun [Latin proestes, a chief, one that presides; proe, before, and sto, to stand, or sisto.]" https://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/priest

Historical religions

In historical polytheism, a priest administers the sacrifice to a deity, often in highly elaborate ritual. In the Ancient Near East, the priesthood also acted on behalf of the deities in managing their property.

Priestesses in antiquity often performed sacred prostitution, and in Ancient Greece, some priestesses such as Pythia, priestess at Delphi, acted as oracles.

Ancient priests and priestesses

- Sumerian en (Akkadian: entu), including Enheduanna (c. 23rd century BCE), were top-ranking priests who were distinguished with special ceremonial attire and held equal status to high priests. They owned property, transacted business, and initiated the hieros gamos with priests and kings.[5]

- Nadītu served as priestesses in the temples of Inanna in the city of Uruk. They were recruited from the highest families in the land and were supposed to remain childless, owned property, and transacted business.

- The Sumerian word nin, EREŠ in Akkadian, is the sign for "lady." nin.dingir (Akkadian entu), literally "divine lady", a priestess.

- In Sumerian epic texts such as "Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta", nu-gig were priestesses in temples dedicated to Inanna and may be a reference to the goddess herself.[6]

- Puabi of Ur was an Akkadian queen regnant or a priestess. In several other Sumerian city-states, the ruling governor or king was also a head priest with the rank of ensi, such as at Lagash.

- Control of the holy city of Nippur and its temple priesthood generally meant hegemony over most of Sumer, as listed on the Sumerian King List; at one point, the Nippur priesthood conferred the title of queen of Sumer on Kugbau, a popular taverness from nearby Kish (who was later deified as Kubaba).

- In the Hebrew Bible, Hebrew: קְדֵשָׁה qědēšā,[7] derived from the root Q-D-Š[8] were sacred prostitutes usually associated with the goddess Asherah.

- Quadishtu served in the temples of the Sumerian goddess Qetesh.

- Ishtaritu specialized in the arts of dancing, music, and singing and they served in the temples of Ishtar.[9]

- In the Epic of Gilgamesh, priestess Shamhat, a temple prostitute, tamed wild Enkidu after "six days and seven nights."

- Gerarai, fourteen Athenian matrons of Dionysus, presided over sacrifices and participated in the festivals of Anthesteria.

Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egyptian religion, the right and obligation to interact with the gods belonged to the pharaoh. He delegated this duty to priests, who were effectively bureaucrats authorized to act on his behalf. Priests staffed temples throughout Egypt, giving offerings to the cult images in which the gods were believed to take up residence and performing other rituals for their benefit.[10] Little is known about what training may have been required of priests, and the selection of personnel for positions was affected by a tangled set of traditions, although the pharaoh had the final say. In the New Kingdom of Egypt, when temples owned great estates, the high priests of the most important cult—that of Amun at Karnak—were important political figures.[11]

High-ranking priestly roles were usually held by men. Women were generally relegated to lower positions in the temple hierarchy, although some held specialized and influential positions, especially that of the God's Wife of Amun, whose religious importance overshadowed the High Priests of Amun in the Late Period.[12]

Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome and throughout Italy, the ancient sanctuaries of Ceres and Proserpina were invariably led by female sacerdotes, drawn from women of local and Roman elites. It was the only public priesthood attainable by Roman matrons and was held in great honor.

A Roman matron was any mature woman of the upper class, married or unmarried. Females could serve public cult as Vestal Virgins but few were chosen, and then only from young maidens of the upper class.[13]

Ancient Greece

- The Pythia was the title of a priestess at the very ancient temple of Delphi that was dedicated to the Earth Mother. She was widely credited for her prophecies. The priestess retained her role when the temple was rededicated to Apollo, giving her a prominence unusual for a woman in the male-dominated culture of classical Greece.

- The Phrygian Sibyl was the priestess presiding over an Apollonian oracle at Phrygia, a historical kingdom in the Anatolian highlands.

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

Historical

After the departure of the Israelites from Egypt, priests in ancient Israel were required by the Law of Moses to be direct patrileneal descendants of Aaron, the elder brother of Moses. In Exodus 30:22–25 God instructs Moses to make a holy anointing-oil to consecrate the priests "for all of eternity". During the times of the two Jewish Temples in Jerusalem, the Aaronic priests performed the daily and special Jewish-holiday offerings and sacrifices within the temples; these offerings are known as the korbanot.

In Hebrew, the word for "priest" is kohen (singular כהן kohen, plural כּהנִים kohanim), hence the family names Cohen, Cahn, Kahn, Kohn, Kogan, etc. Jewish families with these names belong to the tribe of Levi (Levites – descended from Levi, the great-grandfather of Aaron) and in twenty-four instances are called by scripture as such.[14][need quotation to verify] In Hebrew, the word for "priesthood" is kehunnah.

The Hebrew word kohen comes from the root KWN/KON כ-ו-ן 'to stand, to be ready, established'[15] in the sense of "someone who stands ready before God",[16] and has cognates in other Semitic languages, e.g. Phoenician KHN 𐤊𐤄𐤍 "priest" or Arabic kahin كاهن "priest".

Modern Judaism

Since the destruction of the Second Temple, and (therefore) the cessation of the daily and seasonal temple ceremonies and sacrifices, kohanim have become much less prominent. In traditional Judaism (Orthodox Judaism and to some extent, Conservative Judaism) a few priestly and Levitical functions, such as the pidyon haben (redemption of a first-born son) ceremony and the Priestly Blessing, have been retained. Especially in Orthodox Judaism, kohanim remain subject to a number of restrictions concerning matters related to marriage and ritual purity.

Orthodox Judaism regard the kohanim as being held in reserve for a future restored Temple. Kohanim do not perform roles of propitiation, sacrifice, or sacrament in any branch of Rabbinical Judaism or in Karaite Judaism. The principal religious function of any kohanim is to perform the Priestly Blessing, although an individual kohen may also become a rabbi or other professional religious leader.

Beta Israel

The traditional Beta Israel community in Israel had little direct contact with other Jewish groups after the destruction of the temple and developed separately for almost two thousand years. While some Beta Israel now follow Rabbinical Jewish practices, the Ethiopian Jewish religious tradition (Haymanot) uses the word Kahen to refer to a type non-hereditary cleric.

Samaritanism

Aaronic Kohanim also officiated at the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim. The Samaritan kohanim have retained their role as religious leaders.

Christianity

With the spread of Christianity and the formation of parishes, the Greek word ἱερεύς hiereús and Latin word sacerdos, which Christians had since the 3rd century applied to bishops and only in a secondary sense to presbyters, began in the 6th century to be used for presbyters,[17] and is today commonly used for presbyters, distinguishing them from bishops.[18]

Today, the term "priest" is used in the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Church of the East, and many branches of Lutheranism and Anglicanism, to refer to those who have been ordained to a ministerial position through receiving the sacrament of Holy Orders, although "presbyter" is also used.[19] Since the Protestant Reformation, non-sacramental denominations are more likely to use the term "elder" to refer to their pastors. The Christian term "priest" does not have an entry in the Anchor Bible Dictionary, but the dictionary does deal with the above-mentioned terms under the entry for "Sheep, Shepherd."[20]

In Western Christianity, priests are usually styled "The Reverend".

Eastern Orthodoxy

In Orthodoxy, the normal minimum age is thirty (Can. 11 of Neocaesarea) but a bishop may dispense with this if needed. In neither tradition may priests marry after ordination. In the Catholic Church, priests in the Latin Church must be celibate except under special rules for married clergy converting from certain other Christian confessions.[21] Married men may become priests in Eastern Orthodoxy, but cannot marry after ordination, even if they become widowed. In the view of the Eastern Orthodox Churches:

By allowing married men to enter the priesthood, the Orthodox Church affirms the blessedness of marriage without lessening the affirmation of the blessedness of celibacy. St Clement of Alexandria writes: “Celibacy and marriage each have their own functions and specific services to the Lord”, and so “we pay homage to those whom the Lord has favoured with the gift of celibacy and admire monogamy and its dignity” (The Stromata, Book 3). Marriage according to the will of Christ, and celibacy as a devotion to Christ, are two different spiritual paths, equally valid for a true living of the spiritual life. This is so for ordained clergy as it is for everyone else.[22]

Candidates for bishop are chosen only from among the celibate. Orthodox priests will either wear a clerical collar similar to the above-mentioned, or simply a very loose black robe that does not have a collar. The garb of an Eastern Orthodox priest is generally the same as that of an Eastern Catholic or Eastern Lutheran priest.

Oriental Orthodoxy

In the Oriental Orthodox Churches, there are different orders of ministry, each with different vestments.[23] The order of the priest is known as the Kashisho.[23]

In addition to the ministerial priesthood, Oriental Orthodoxy does affirm the priesthood of believers, which is called the Ulmoyo.[23]

Catholicism

The most significant liturgical acts reserved to priests in these traditions are the administration of the Sacraments, including the celebration of the Holy Mass or Divine Liturgy (the terms for the celebration of the Eucharist in the Latin and Byzantine traditions, respectively), and the Sacrament of Reconciliation, also called Confession. The sacraments of Anointing of the Sick (Extreme Unction) and Confirmation are also administered by priests, though in the Western tradition Confirmation is ordinarily celebrated by a bishop. In the East, Chrismation is performed by the priest (using oil specially consecrated by a bishop) immediately after Baptism, and Unction is normally performed by several priests (ideally seven), but may be performed by one if necessary. In the West, Holy Baptism may be celebrated by anyone. The Vatican catechism states that "According to Latin tradition, the spouses as ministers of Christ's grace mutually confer upon each other the sacrament of Matrimony".[24] Thus marriage is a sacrament administered by the couple to themselves, but may be witnessed and blessed by a deacon, or priest (who usually administers the ceremony). In the East, Holy Baptism and Marriage (which is called "Crowning") may be performed only by a priest. If a person is baptized in extremis (i.e., when in fear of immediate death), only the actual threefold immersion together with the scriptural words[25] may be performed by a layperson or deacon. The remainder of the rite, and Chrismation, must still be performed by a priest, if the person survives. The only sacrament which may be celebrated only by a bishop is that of Ordination (cheirotonia, "Laying-on of Hands"), or Holy Orders. In these traditions, only men who meet certain requirements may become priests. In Catholicism, the canonical minimum age is twenty-five. Bishops may dispense with this rule and ordain men up to one year younger. Dispensations of more than a year are reserved to the Holy See (Can. 1031 §§ 1, 4.) A Catholic priest must be incardinated by his bishop or his major religious superior in order to engage in public ministry. Secular priests are incardinated into a diocese, whereas religious priests live the consecrated life and can work anywhere in the world that their specific community operates.

Married men may become priests in the Eastern Catholic Churches, but cannot marry after ordination, even if they become widowed.

Lutheranism

Conservative Lutheran reforms are reflected in the theological and practical view of the ministry of the church. Much of European Lutheranism follows the traditional Catholic governance of deacon, priest, and bishop. The Lutheran archbishops of Finland, Sweden, etc. and Baltic countries are the historic national primates and some ancient cathedrals and parishes in the Lutheran church were constructed many centuries before the Reformation. Indeed, ecumenical work within the Moravian Church, Anglican Communion and among Scandinavian Lutherans mutually recognize the historic apostolic legitimacy and full communion. Likewise in America, Lutherans have embraced the apostolic succession of bishops in the full communion with Moravians and Episcopalians. Most Lutheran ordinations are performed by a bishop.

The Church of Sweden has a threefold ministry of bishop, priest, and deacon and those ordained to the presbyterate are referred to as priests.[26] In the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, ordained presbyters are referred to by various publications, including Finnish ones, as pastors,[27][28] or priests.[29][30] In the United States, denominations like the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod use the terms "reverend" and "pastor" interchangeably for ordained members of the clergy;[31] the Lutheran Church - International, a Confessional Lutheran denomination of Evangelical Catholic churchmanship, uses the term "priest" for those ordained to the presbyterate, who are addressed as "Father".[32]

Apart from the ministerial priesthood, the general priesthood or the priesthood of all believers, is a Christian doctrine derived from several passages of the New Testament. It is a foundational concept of Protestantism.[33] It is this doctrine that Martin Luther adduces in his 1520 To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation in order to dismiss the medieval Christian belief that Christians were to be divided into two classes: "spiritual" and "temporal" or non-spiritual.

Anglican or Episcopalian

The role of a priest in the Anglican Communion and the Free Church of England is largely the same as within the Roman Catholic Church and Eastern Christianity, except that canon law in almost every Anglican province restricts the administration of confirmation to the bishop, just as with ordination. Although Anglican priests who are members of religious orders must remain celibate (although there are exceptions, such as priests in the Anglican Order of Cistercians), the secular clergy—bishops, priests, and deacons who are not members of religious orders—are permitted to marry before or after ordination (although in most provinces they are not permitted to marry a person of the same sex). The Anglican churches, unlike the Roman Catholic or Eastern Christian traditions, have allowed the ordination of women as priests (referred to as "priests" not "priestesses") in some provinces since 1971.[34] This practice remains controversial, however; a minority of provinces (10 out of the 38 worldwide) retain an all-male priesthood.[35] Most Continuing Anglican churches do not ordain women to the priesthood.

As Anglicanism represents a broad range of theological opinion, its presbyterate includes priests who consider themselves no different in any respect from those of the Roman Catholic Church, and a minority who prefer to use the title presbyter in order to distance themselves from the more sacrificial theological implications which they associate with the word priest.

While priest is the official title of a member of the presbyterate in every Anglican province worldwide (retained by the Elizabethan Settlement), the ordination rite of certain provinces (including the Church of England) recognizes the breadth of opinion by adopting the title The Ordination of Priests (also called Presbyters). Even though both words mean 'elders' historically the term priest has been more associated with the "High Church" or Anglo-Catholic wing, whereas the term "minister" has been more commonly used in "Low Church" or Evangelical circles.[36]

Latter Day Saints

In the Latter Day Saint movement, the priesthood is the power and authority of God given to man, including the authority to perform ordinances and to act as a leader in the church. A body of priesthood holders is referred to as a quorum. Priesthood denotes elements of both power and authority. The priesthood includes the power Jesus gave his apostles to perform miracles such as the casting out of devils and the healing of sick (Luke 9:1). Latter Day Saints believe that the Biblical miracles performed by prophets and apostles were performed by the power of the priesthood, including the miracles of Jesus, who holds all of the keys of the priesthood. The priesthood is formally known as the "Priesthood after the Order of the Son of God", but to avoid the too frequent use of the name of deity, the priesthood is referred to as the Melchizedek priesthood (Melchizedek being the high priest to whom Abraham paid tithes). As an authority, the priesthood is the authority by which a bearer may perform ecclesiastical acts of service in the name of God. Latter Day Saints believe that acts (and in particular, ordinances) performed by one with priesthood authority are recognized by God and are binding in heaven, on earth, and in the afterlife.

There is some variation among the Latter Day Saint denominations regarding who can be ordained to the priesthood. In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), all worthy males above the age of 12 can be ordained to the priesthood. However, prior to a policy change in 1978, the LDS Church did not ordain men or boys who were of black African descent. The LDS Church does not ordain women to any of its priesthood offices. The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now the Community of Christ), the second largest denomination of the movement, began ordaining women to all of its priesthood offices in 1984. This decision was one of the reasons that led to a schism in the church, which prompted the formation of the independent Restoration Branches movement from which other denominations have sprung, including the Remnant Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

Islam

Islam has no sacerdotal priesthood. There are, however, a variety of academic and administrative offices which have evolved to assist Muslims with this task, such as the imāms and the mullāhs.

Mandaeism

A Mandaean priest refers to an ordained religious leader in Mandaeism. In Mandaean scriptures, priests are referred to as Naṣuraiia (Naṣoraeans).[37] All priests must undergo lengthy ordination ceremonies, beginning with tarmida initiation.[38] Mandaean religious leaders and copyists of religious texts hold the title Rabbi or in Arabic 'Sheikh'.[39][40]

All Mandaean communities traditionally require the presence of a priest, since priests are required to officiate over all important religious rituals, including masbuta, masiqta, birth and wedding ceremonies. Priests also serve as teachers, scribes, and community leaders.[38]

There are three types of priests in Mandaeism:[38]

- rišama "leader of the people"

- ganzibria "treasurers" (from Old Persian ganza-bara "id.," Neo-Mandaic ganzeḇrānā)

- tarmidia "disciples" (Neo-Mandaic tarmidānā)

Priests have lineages based on the succession of ganzibria priests who had initiated them. Priestly lineages, which are distinct from birth lineages, are typically recorded in the colophons of many Mandaean texts. The position is not hereditary, and any Mandaean male who is highly knowledgeable about religious matters is eligible to become a priest.[41]

Eastern religions

Hinduism

A Hindu priest traditionally comes from the Brahmin community.[42][43] Priests are ordained and trained before practicing. Their training consists of a precise memorisation of texts in a written or printed form and learning how to pronouciate and recite these texts from a guru.[44] There are two types of Hindu priests, pujaris (swamis, yogis, and gurus) and purohitas (pandits). A pujari performs rituals in a temple. These rituals include bathing the murtis (the statues of the gods/goddesses), performing puja (a ritualistic offering of various items to the gods), and waving a ghee or oil lamp (an offering in light) known in Hinduism as aarti, before the murtis. Pujaris are often married.

A purohita, on the other hand, performs rituals and saṃskāras (sacraments), yajnas (sacrifices) outside the temple. There are special purohitas who perform only funeral rites.

In many cases, a purohita also functions as a pujari.

While only men have traditionally been ordained as priests, recent developments, such as feminism in India, have led to the opening of training schools for women to become priests.[45]

Zoroastrianism

A Zoroastrian priest are called a Mobad and they officiate the Yasna, pouring libations into the sacred fire to the accompaniment of ritual chants. The Mobad also prepare drinks for the haoma ritual.[46]

In Indian Zoroastrianism, the priesthood is reserved for men and is a mostly hereditary position,[47] but women have been ordained in Iran and North America as a mobedyar, meaning an assistant mobed.[48][49]

Taoism

The Taoist priests (道士 "master of the Dao" p. 488) act as interpreters of the principles of Yin-Yang 5 elements (fire, water, soil, wood, and metal p. 53) school of ancient Chinese philosophy, as they relate to marriage, death, festival cycles, and so on. The Taoist priest seeks to share the benefits of meditation with his or her community through public ritual and liturgy (p. 326). In the ancient priesthood before the Tang, the priest was called Jijiu ("libationer" p. 550), with both male and female practitioners selected by merit. The system gradually changed into a male only hereditary Taoist priesthood until more recent times (p. 550,551).[50]

Indigenous and ethnic religions

Shinto

The Shinto priest is called a kannushi (神主; lit. "Master of the kami"), originally pronounced kamunushi, sometimes referred to as a shinshoku (神職). A kannushi is the person responsible for the maintenance of a Shinto shrine, or jinja, purificatory rites, and for leading worship and veneration of a certain kami. Additionally, kannushi are aided by another priest class, miko (巫女; "shrine maidens"), for many rites. The maidens may either be family members in training, apprentices, or local volunteers.

Saiin were female relatives of the Japanese emperor (termed saiō) who served as High Priestesses in Kamo Shrine. Saiō also served at Ise Shrine. Saiin priestesses usually were elected from royalty. In principle, Saiin remained unmarried, but there were exceptions. Some Saiin became consorts of the emperor, called Nyōgo in Japanese. The Saiin order of priestesses existed throughout the Heian and Kamakura periods.

Africa

The Yoruba people of western Nigeria practice an indigenous religion with a chiefly hierarchy of priests and priestesses that dates to AD 800–1000.[51] Ifá priests and priestesses bear the titles Babalawo for men and Iyanifa for women.[52] Priests and priestesses of the varied Orisha are titled Babalorisa for men and Iyalorisa for women.[53] Initiates are also given an Orisa or Ifá name that signifies under which deity they are initiated. For example, a Priestess of Osun may be named Osunyemi, and a Priest of Ifá may be named Ifáyemi. This traditional culture continues to this day as initiates from all around the world return to Nigeria for initiation into the priesthood, and varied derivative sects in the New World (such as Cuban Santería and Brazilian Umbanda) use the same titles to refer to their officers as well.

In a kingdom, tribe or clan in Africa the traditional leader is also a priest cause of his mission between the spirit of ancestors ( Throne ) and people. Everything the traditional ruler must do, is according to the ritual, ceremony and worship. They call him sometimes royal Priest.[54]

Afro-Latin American religions

In Brazil, the priests in the Umbanda, Candomblé and Quimbanda religions are called pai-de-santo (literally "Father of saint" in English), or "babalorixá" (a word borrowed from Yoruba bàbálórìsà, meaning Father of the Orisha); its female equivalent is the mãe-de-santo ("Mother of saint"), also referred to as "ialorixá" (Yoruba: iyálórìsà).

In the Cuban Santería, a male priest is called Santero, while female priests are called Iyanifas or "mothers of wisdom".[55]

Neo-paganism

Wicca

According to traditional Wiccan beliefs, every member of the religion is considered a priestess or priest, as it is believed that no person can stand between another and the divine. However, in response to the growing number of Wiccan temples and churches, several denominations of the religion have begun to develop a core group of ordained priestesses and priests serving a larger laity. This trend is far from widespread, but is gaining acceptance due to increased interest in the religion.[56][57][58]

Dress

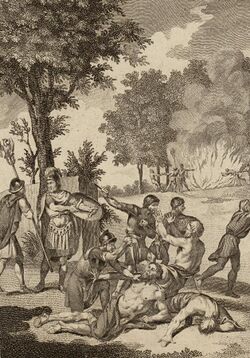

The dress of religious workers in ancient times may be demonstrated in frescoes and artifacts from the cultures. The dress is presumed to be related to the customary clothing of the culture, with some symbol of the deity worn on the head or held by the person. Sometimes special colors, materials, or patterns distinguish celebrants, as the white wool veil draped on the head of the Vestal Virgins.

Occasionally, the celebrants at religious ceremonies shed all clothes in a symbolic gesture of purity. This was often the case in ancient times. An example of this is shown to the left on a Kylix dating from c. 500 BC where a priestess is featured. Modern religious groups tend to avoid such symbolism and some may be quite uncomfortable with the concept.

The retention of long skirts and vestments among many ranks of contemporary priests when they officiate may be interpreted to express the ancient traditions of the cultures from which their religious practices arose.

In most Christian traditions, priests wear clerical clothing, a distinctive form of street dress. Even within individual traditions it varies considerably in form, depending on the specific occasion. In Western Christianity, the stiff white clerical collar has become the nearly universal feature of priestly clerical clothing, worn either with a cassock or a clergy shirt. The collar may be either a full collar or a vestigial tab displayed through a square cutout in the shirt collar.

Eastern Christian priests mostly retain the traditional dress of two layers of differently cut cassock: the rasson (Greek) or podriasnik (Russian) beneath the outer exorasson (Greek) or riasa (Russian). If a pectoral cross has been awarded it is usually worn with street clothes in the Russian tradition, but not so often in the Greek tradition.

Distinctive clerical clothing is less often worn in modern times than formerly, and in many cases it is rare for a priest to wear it when not acting in a pastoral capacity, especially in countries that view themselves as largely secular in nature. There are frequent exceptions to this however, and many priests rarely if ever go out in public without it, especially in countries where their religion makes up a clear majority of the population. Pope John Paul II often instructed Catholic priests and religious to always wear their distinctive (clerical) clothing, unless wearing it would result in persecution or grave verbal attacks.

Christian traditions that retain the title of priest also retain the tradition of special liturgical vestments worn only during services. Vestments vary widely among the different Christian traditions.

In modern Pagan religions, such as Wicca, there is no one specific form of dress designated for the clergy. If there is, it is a particular of the denomination in question, and not a universal practice. However, there is a traditional form of dress, (usually a floor-length tunic and a knotted cord cincture, known as the cingulum), which is often worn by worshipers during religious rites. Among those traditions of Wicca that do dictate a specific form of dress for its clergy, they usually wear the traditional tunic in addition to other articles of clothing (such as an open-fronted robe or a cloak) as a distinctive form of religious dress, similar to a habit.[59][60]

Assistant priest

In many religions, there are one or more layers of assistant priests.

In the Ancient Near East, hierodules served in temples as assistants to the priestess.

In ancient Judaism, the Priests (Kohanim) had a whole class of Levites as their assistants in making the sacrifices, in singing psalms and in maintaining the Temple. The Priests and the Levites were in turn served by servants called Nethinim. These lowest level of servants were not priests.

In the Catholic Church the term assistant priest applies to a minister assisting the main celebrant, whether it is the Pope, a bishop, or another priest, at a Mass or the Divine Office.[61]

An assistant priest is a priest in the Anglican and Episcopal churches who is not the senior member of clergy of the parish to which they are appointed, but is nonetheless in priests' orders; there is no difference in function or theology, merely in 'grade' or 'rank'. Some assistant priests have a "sector ministry", that is to say that they specialize in a certain area of ministry within the local church, for example youth work, hospital work, or ministry to local light industry. They may also hold some diocesan appointment part-time. In most (though not all) cases, an assistant priest has the legal status of assistant curate, although not all assistant curates are priests, as this legal status also applies to many deacons working as assistants in a parochial setting.

The corresponding term in the Catholic Church is "parochial vicar" – an ordained priest assigned to assist the pastor (Latin: parochus) of a parish in the pastoral care of parishioners. Normally, all pastors are also ordained priests; occasionally an auxiliary bishop will be assigned that role.

In Wicca, the leader of a coven or temple (either a high priestess or high priest) often appoints an assistant. This assistant is often called a 'deputy', but the more traditional terms 'maiden' (when female and assisting a high priestess) and 'summoner' (when male and assisting a high priest) are still used in many denominations.

See also

- Archpriest

- Brahmin

- Gothi

- Hieromonk

- Jogi (caste)

- List of fictional clergy and religious figures

- Presbyterorum Ordinis, decree on the priesthood from the Second Vatican Council

- Priest shortage

- Ritualism in the Church of England

- Sacerdotalism

- Vicar

- Volkhv

References

- ↑ Momigliano, Arnaldo (1984). "Georges Dumézil and the Trifunctional Approach to Roman Civilization". History and Theory 23 (3): 312–330. doi:10.2307/2505078. ISSN 0018-2656. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2505078.

- ↑ Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language, College Edition, The World Publishing Company, Cleveland OH, s.v. "priest"

- ↑ "priest". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Joseph B. Lightfoot, Epistle to the Philippians; a revised text, with introduction, etc., 2nd ed. 1869, p. 184, cited after OED.

- ↑ Dening, Sarah (1996). The Mythology of Sex – Ch.3. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-861207-2. https://archive.org/details/mythologyofsexan0000deni.

- ↑ Black, Jeremy (1998). Reading Sumerian Poetry. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-485-93003-X. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jj3bi8QAm1AC&pg=PA142.

- ↑ "Hebrew Lexicon :: H6948 (KJV)". cf.blueletterbible.org. http://cf.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H06948&t=kjv.

- ↑ "Strong's H6948" (in en). https://www.blueletterbible.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?t=kjv&strongs=h6948., incorporating Strong's Concordance (1890) and Gesenius's Lexicon (1857).

- ↑ Prioreschi, Plinio (1996). "A History of Medicine: Primitive and ancient medicine". Mellen History of Medicine (Horatius Press) 1: 376. ISBN 978-1-888456-01-1. PMID 11639620. https://books.google.com/books?id=MJUMhEYGOKsC&pg=PA376.

- ↑ Sauneron, Serge (2000). The Priests of Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press. pp. 32–36, 89–92. ISBN 0-8014-8654-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=J9yureoueAEC.

- ↑ Sauneron, Serge (2000). The Priests of Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press. pp. 42–47, 52–53. ISBN 0-8014-8654-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=J9yureoueAEC.

- ↑ Doxey, Denise M., "Priesthood", in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt (2001), vol. III, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Barbette Stanley Spaeth, The Roman goddess Ceres, University of Texas Press, 1996, pp. 4–5, 9, 20 (historical overview and Aventine priesthoods), 84–89 (functions of plebeian aediles), 104–106 (women as priestesses): citing among others Cicero, In Verres, 2.4.108; Valerius Maximus, 1.1.1; Plutarch, De Mulierum Virtutibus, 26.

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud to Mishnaic tractate Maaser Sheini p. 31a.

- ↑ Even-Shoshan, Avraham (2003). Even-Shoshan Dictionary. pp. Entry "כֹּהֵן" (Kohen).

- ↑ "Klein Dictionary, כֹּהֵן". https://www.sefaria.org/Klein_Dictionary,_כֹּהֵן.

- ↑ Garhammer, Erich (2005). "Priest, Priesthood 3. Roman Catholicism". in Erwin Fahlbusch. Encyclopedia of Christianity. 4. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 348. ISBN 978-0-8028-2416-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=C5V7oyy69zgC&q=%22same+tasks+as+bishops%22&pg=PA348. Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ↑ Dennis Chester Smolarski, Sacred Mysteries (Paulist Press 1995 ISBN 978-0-8091-3551-6), p. 128. Paulist Press. 1995. ISBN 978-0-8091-3551-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=VrLnu1RiyVgC&dq=Smolarski+%22priests+and+presbyters%22&pg=PA128. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ An example of the use of "presbyter" is found in Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1554

- ↑ Vancil, Jack W. (1992). "Sheep, Shepherd" The Anchor Bible Dictionary New York: Doubleday. 5, 1187–1190. ISBN 0-385-19363-7.

- ↑ Miller, Michael (May 17, 2008). "Peoria diocese ordains its first married priest". Peoria Journal Star: p. C8. https://rentapriest.blogspot.com/2008/05/peoria-diocese-ordains-its-first.html. "About 100 Episcopal priests, many of them married, have become Roman Catholic priests since a "pastoral provision" was created by Pope John Paul II in 1980, said [Doug] Grandon, director of catechetics for the diocese. [...] His family life will remain the same, he said. Contrary to popular misunderstandings, he won't have to be celibate."

- ↑ Toumbelekis, Pandelis (2014). "Why does the Orthodox Church have married priests?" (in en). Greek Orthodox Christian Society. https://lychnos.org/why-does-the-orthodox-church-have-married-priests/.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "Different Orders of Priesthood in Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church" (in en). Manna. 27 October 2019. https://mannaghaziabad.com/post/44/differentorders-of-priesthood-in-malankara-orthodox-syrian-church-explaining-theresponsibilities-and-vestments-of-each-order.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – The sacrament of Matrimony". vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p2s2c3a7.htm.

- ↑ Matthew 28:19

- ↑ "Ministry and Ministries – Svenska kyrkan". Svenskakyrkan.se. 2021-09-20. https://www.svenskakyrkan.se/ministry-and-ministries. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ↑ "Parishes". evl.fi. https://evl.fi/the-church/organisation/parishes. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ↑ "Women ordained for thirty years". evl.fi. 1988-03-06. https://evl.fi/current-issues/women-ordained-for-thirty-years. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ↑ Sequeira, Tahira (8 February 2021). "Gallery: Turku makes history with first female bishop". Helsinki Times. https://www.helsinkitimes.fi/finland/news-in-brief/18657-gallery-turku-makes-history-with-first-female-bishop.html. "Leppänen also became the first woman from the Conservative Laestadian movement (a revival movement within the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland) to be ordained as a priest in 2012. The first female priests were ordained in Finland 32 years ago."

- ↑ Doe, Norman (4 August 2011) (in en). Law and Religion in Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-19-960401-2. "In Finland, a priest of the Lutheran church is forbidden to reveal a secret received in confession and in the course of pastoral counselling; a similar rule applies to Orthodox priests."

- ↑ "Paramount Christian". https://www.paramountchristian.org/christianity-around-the-world/often-asked-when-did-lutheranism-become-the-most-followed-christianity-religion.html.

- ↑ "Bulletin: Pentecost and Ordinary Time 2024" (in English). LC-I. 2024. https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/2dd65e00-9688-4351-8bdc-a3bf83abb8e9/downloads/219ba6b3-b13b-4b50-9548-e811974643b4/LC%E2%80%93I%20BULLETIN%202024-09.pdf?ver=1736526623701.

- ↑ "The Protestant Heritage". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9109446. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ Emma John (July 4, 2010). "Should women ever be bishops?". The Observer (London). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/jul/04/should-women-ever-be-made-bishops.

- ↑ Sulaiman Kakaire. "Male bishops speak out on female priests". https://www.observer.ug/news-headlines/9899-male-bishops-speak-out-on-female-priests.

- ↑ Anglican Church of Canada. "Minister or Priest?". http://www.anglican.ca/help/faq/minister-or-priest/.

- ↑ Drower, E. S. 1960. The Secret Adam: A Study of Nasoraean Gnosis. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002). The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515385-5. OCLC 65198443. http://mandaeannetwork.com/Mandaean/books/english/2The_Mandaeans_Ancient_Texts_and_Modern_People_American_Academy_of_Religion_Books_Jorunn_Jacobsen_Buckley.pdf?bcsi_scan_955b0cd764557e80=0&bcsi_scan_filename=2The_Mandaeans_Ancient_Texts_and_Modern_People_American_Academy_of_Religion_Books_Jorunn_Jacobsen_Buckley.pdf.

- ↑ McGrath, James F. (2010). "Reading the Story of Miriai on Two Levels: Evidence from Mandaean Anti-Jewish Polemic about the Origins and Setting of Early Mandaeism". pp. 583–592. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1194&context=facsch_papers.

- ↑ Holy Spirit University of Kaslik – USEK (27 November 2017), Open discussion with the Sabaeans Mandaeans, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AdQq4GkT5Ao, retrieved 10 December 2021

- ↑ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). The great stem of souls: reconstructing Mandaean history. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-621-9.

- ↑ Herman, A. L. (2018-05-04) (in en). A Brief Introduction To Hinduism: Religion, Philosophy, And Ways Of Liberation. Routledge. pp. 52. ISBN 978-0-429-98238-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z0haDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA52.

- ↑ Parsons, Gerald (1993) (in en). The Growth of Religious Diversity: Traditions. Psychology Press. pp. 197. ISBN 978-0-415-08326-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=vM--pQp5qBUC&pg=PA197.

- ↑ Fuller, C. J. (2001). "Orality, Literacy and Memorization: Priestly Education in Contemporary South India". Modern Asian Studies 35 (1): 3. ISSN 0026-749X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/313087.

- ↑ Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2010-03-10) (in en). A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition. State University of New York Press. pp. 324. ISBN 978-0-7914-8011-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=8CVviRghVtIC&pg=PA324.

- ↑ Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians, their religious beliefs and practices. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23902-8.

- ↑ Nigosian, Solomon Alexander (1993), The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition and Modern Research, Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's University Press, p. 104, ISBN 0-7735-1144-X, OCLC 243566889

- ↑ Wadia, Arzan Sam (March 9, 2011), "The Jury Is Still Out On Women as Parsi Priests", parsikhabar.net (Parsi Khabar), http://parsikhabar.net/religion/the-jury-is-still-out-on-women-as-parsi-priests/2968/

- ↑ Khosraviani, Mahshad (June 19, 2013), "Sedreh Pooshi by Female Mobedyar in Toronto-Canada", parsinews.net (Parsi News), http://www.parsinews.net/sedreh-pooshi-by-female-mobedyar-in-toronto-canada/3922.html?fb_source=pubv1, retrieved October 10, 2014

- ↑ Pregadio, Fabrizio (2008) The Encyclopedia of Taoism, Volume 1 Psychology Press ISBN 0700712003

- at Google books: pp. 488–90 • pp. 53–54 • pp. 326–29 • pp. 550–51

- ↑ Akintoye, S. A. (2010). A History of the Yoruba People. Dakar, Senegal. ISBN 978-2-35926-005-2. OCLC 609888714.

- ↑ Asante, M.K.; Mazama, A. (2009). Encyclopedia of African Religion. 1. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-3636-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=B667ATiedQkC&pg=PT365. Retrieved 2015-07-25.

- ↑ Walter, M.N.; Fridman, E.J.N. (2004). Shamanism: An Encyclopedia of World Beliefs, Practices, and Culture. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 451. ISBN 978-1-57607-645-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=X8waCmzjiD4C&pg=PA451. Retrieved 2015-07-25.

- ↑ "Royal priesthood". https://www.linguee.fr.

- ↑ AfricaNews (October 10, 2022). "The Cuban priestesses defying religious patriarchy" (in en). https://www.africanews.com/2022/10/10/the-cuban-priestesses-defying-religious-patriarchy/.

- ↑ "Priesthood". Paganwiccan.about.com. 2014-03-04. http://paganwiccan.about.com/od/glossary/g/Priesthood.htm.

- ↑ "Leadership". Patheos.com. http://www.patheos.com/Library/Pagan/Ethics-Morality-Community/LeadershipClergy.html.

- ↑ "The Priesthood – Temple of the Good Game". Goodgame.org.nz. http://www.goodgame.org.nz/priesthood.html.

- ↑ Kennerson, Robert (2022-12-17). "The Garb Of The Clergy – Pagan Christianity". https://www.wilmingtonfavs.com/pagan-christianity/the-garb-of-the-clergy.html.

- ↑ Beckett, John (2017-02-12). "How Should Pagan Clergy Dress?". https://www.patheos.com/blogs/johnbeckett/2017/02/pagan-clergy-dress.html.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Assistant Priest". https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12407a.htm.

External links

- Description of the problem of Roman Catholic and Old Catholic reunion with respect to the female priesthood

Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "Priest". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "Priest". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Template:Sacraments of the Assyrian Church of the East Template:Lutheran Divine Service

|

KSF

KSF