Theogony

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

The Theogony (Greek: Θεογονία, Theogonía, grc-x-attic, i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods"[1]) is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed c. 730–700 BC.[2] It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contains 1022 lines.

Descriptions

Hesiod's Theogony is a large-scale synthesis of a vast variety of local Greek traditions concerning the gods, organized as a narrative that tells how they came to be and how they established permanent control over the cosmos. It is the first known Greek mythical cosmogony. The initial state of the universe is chaos, a dark indefinite void considered a divine primordial condition from which everything else appeared. Theogonies are a part of Greek mythology which embodies the desire to articulate reality as a whole; this universalizing impulse was fundamental for the first later projects of speculative theorizing.[3]

Further, in the "Kings and Singers" passage (80–103)[4] Hesiod appropriates to himself the authority usually reserved to sacred kingship. The poet declares that it is he, where we might have expected some king instead, upon whom the Muses have bestowed the two gifts of a scepter and an authoritative voice (Hesiod, Theogony 30–3), which are the visible signs of kingship. It is not that this gesture is meant to make Hesiod a king. Rather, the point is that the authority of kingship now belongs to the poetic voice, the voice that is declaiming the Theogony.

Although it is often used as a sourcebook for Greek mythology,[5] the Theogony is both more and less than that. In formal terms it is a hymn invoking Zeus and the Muses: parallel passages between it and the much shorter Homeric Hymn to the Muses make it clear that the Theogony developed out of a tradition of hymnic preludes with which an ancient Greek rhapsode would begin his performance at poetic competitions. It is necessary to see the Theogony not as the definitive source of Greek mythology, but rather as a snapshot of a dynamic tradition that happened to crystallize when Hesiod formulated the myths he knew—and to remember that the traditions have continued evolving since that time.

The written form of the Theogony was established in the 6th century BC. Even some conservative editors have concluded that the Typhon episode (820–68) is an interpolation.[6]

Hesiod was probably influenced by some Near-Eastern traditions, such as the Babylonian Dynasty of Dunnum,[7] which were mixed with local traditions, but they are more likely to be lingering traces from the Mycenaean tradition than the result of oriental contacts in Hesiod's own time.

The decipherment of Hittite mythical texts, notably the Kingship in Heaven text first presented in 1946, with its castration mytheme, offers in the figure of Kumarbi an Anatolian parallel to Hesiod's Uranus–Cronus conflict.[8]

The succession myth

One of the principal components of the Theogony is the presentation of what is called the "succession myth", which tells how Cronus overthrew Uranus, and how in turn Zeus overthrew Cronus and his fellow Titans, and how Zeus was eventually established as the final and permanent ruler of the cosmos.[9]

Uranus (Sky) initially produced eighteen children with his mother Gaia (Earth): the twelve Titans, the three Cyclopes, and the three Hecatoncheires (Hundred-Handers),[10] but hating them,[11] he hid them away somewhere inside Gaia.[12] Angry and in distress, Gaia fashioned a sickle made of adamant and urged her children to punish their father. Only her son Cronus, the youngest Titan, was willing to do so.[13] So Gaia hid Cronus in "ambush" and gave him the adamantine sickle, and when Uranus came to lie with Gaia, Cronus reached out and castrated his father.[14] This enabled the Titans to be born and Cronus to assume supreme command of the cosmos.[15]

Cronus, having now taken over control of the cosmos from Uranus, wanted to ensure that he maintained control. Uranus and Gaia had prophesied to Cronus that one of Cronus' own children would overthrow him, so when Cronus married Rhea, he made sure to swallow each of the children she birthed: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus (in that order), to Rhea's great sorrow.[16] However, when Rhea was pregnant with Zeus, Rhea begged her parents Gaia and Uranus to help her save Zeus. So they sent Rhea to Lyctus on Crete to bear Zeus, and Gaia took the newborn Zeus to raise, hiding him deep in a cave beneath Mount Aigaion.[17] Meanwhile, Rhea gave Cronus a huge stone wrapped in baby's clothes which he swallowed thinking that it was another of Rhea's children.[18]

Zeus, now grown, forced Cronus (using some unspecified trickery of Gaia) to disgorge his other five children.[19] Zeus then released his uncles the Cyclopes (apparently still imprisoned beneath the earth, along with the Hundred-Handers, where Uranus had originally confined them) who then provide Zeus with his great weapon, the thunderbolt, which had been hidden by Gaia.[20] A great war was begun, the Titanomachy, between the new gods, Zeus and his siblings, and the old gods, Cronus and the Titans, for control of the cosmos. In the tenth year of that war, following Gaia's counsel, Zeus released the Hundred-Handers, who joined the war against the Titans, helping Zeus to gain the upper hand. Zeus then cast the fury of his thunderbolt at the Titans, defeating them and throwing them into Tartarus,[21] thus ending the Titanomachy.

A final threat to Zeus' power was to come in the form of the monster Typhon, son of Gaia and Tartarus. Zeus with his thunderbolt was quickly victorious, and Typhon was also imprisoned in Tartarus.[22]

Zeus, by Gaia's advice, was elected king of the gods, and he distributed various honors among the gods.[23] Zeus then married his first wife Metis, but when he learned that Metis was fated to produce a son which might overthrow his rule, by the advice of Gaia and Uranus, Zeus swallowed Metis (while still pregnant with Athena). And so Zeus managed to end the cycle of succession and secure his eternal rule over the cosmos.[24]

The genealogies

The first gods

The world began with the spontaneous generation of four beings: first arose Chaos (Chasm); then came Gaia (Earth), "the ever-sure foundation of all"; "dim" Tartarus, in the depths of the Earth; and Eros (Desire) "fairest among the deathless gods".[25] From Chaos came Erebus (Darkness) and Nyx (Night). And Nyx "from union in love" with Erebus produced Aether (Brightness) and Hemera (Day).[26] From Gaia came Uranus (Sky), the Ourea (Mountains), and Pontus (Sea).[27]

| The first gods [28] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Children of Gaia and Uranus

Uranus mated with Gaia, and she gave birth to the twelve Titans: Oceanus, Coeus, Crius, Hyperion, Iapetus, Theia, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, Tethys and Cronus;[29] the Cyclopes: Brontes, Steropes and Arges;[30] and the Hecatoncheires ("Hundred-Handers"): Cottus, Briareos, and Gyges.[31]

| Children of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Sky) [32] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Children of Gaia and Uranus' blood, and Uranus' genitals

When Cronus castrated Uranus, from Uranus' blood which splattered onto the earth, came the Erinyes (Furies), the Giants, and the Meliai. Cronus threw the severed genitals into the sea, around which foam developed and transformed into the goddess Aphrodite.[33]

| Children of Gaia and Uranus' blood, and Uranus' genitals [34] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Descendants of Nyx

Meanwhile, Nyx (Night) alone produced children: Moros (Doom), Ker (Destiny), Thanatos (Death), Hypnos (Sleep), Oneiroi (Dreams), Momus (Blame), Oizys (Pain), Hesperides (Daughters of Night), Moirai (Fates),[35] Keres (Destinies), Nemesis (Retribution), Apate (Deceit), Philotes (Love), Geras (Old Age), and Eris (Discord).[36]

And from Eris alone, came Ponos (Hardship), Lethe (Forgetfulness), Limos (Starvation), Algea (Pains), Hysminai (Battles), Makhai (Wars), Phonoi (Murders), Androktasiai (Manslaughters), Neikea (Quarrels), Pseudea (Lies), Logoi (Stories), Amphillogiai (Disputes), Dysnomia (Anarchy), Ate (Ruin), and Horkos (Oath).[37]

| Children of Nyx (Night) and Eris (Discord)[38] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Descendants of Gaia and Pontus

After Uranus's castration, Gaia mated with her son Pontus (Sea) producing a descendent line consisting primarily of sea deities, sea nymphs, and hybrid monsters. Their first child Nereus (Old Man of the Sea) married Doris, one of the Oceanid daughters of the Titans Oceanus and Tethys, and they produced the Nereids, fifty sea nymphs, which included Amphitrite, Thetis, and Psamathe. Their second child Thaumas, married Electra, another Oceanid, and their offspring were Iris (Rainbow) and the two Harpies: Aello and Ocypete.[40]

Gaia and Pontus' third and fourth children, Phorcys and Ceto, married each other and produced the two Graiae: Pemphredo and Enyo, and the three Gorgons: Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. Poseidon mated with Medusa and two offspring, the winged horse Pegasus and the warrior Chrysaor, were born when the hero Perseus cut off Medusa's head. Chrysaor married Callirhoe, another Oceanid, and they produced the three-headed Geryon.[41] Next comes the half-nymph half-snake Echidna[42] (her mother is unclear, probably Ceto, or possibly Callirhoe).[43] The last offspring of Ceto and Phorcys was a serpent (unnamed in the Theogony, later called Ladon, by Apollonius of Rhodes) who guards the golden apples.[44]

| Descendants of Gaia and Pontus (Sea), and Phorcys and Ceto[45] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Descendants of Echidna and Typhon

Gaia also mated with Tartarus to produce Typhon,[53] whom Echidna married, producing several monstrous descendants.[54] Their first three offspring were Orthus, Cerberus, and the Hydra. Next comes the Chimera (whose mother is unclear, either Echidna or the Hydra).[55] Finally Orthus (his mate is unclear, either the Chimera or Echidna) produced two offspring: the Sphinx and the Nemean Lion.[56]

| Descendants of Echidna and Typhon[57] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Descendants of the Titans

The Titans, Oceanus, Hyperion, Coeus, and Cronus married their sisters Tethys, Theia, Phoebe and Rhea, and Crius married his half-sister Eurybia, the daughter of Gaia and her son, Pontus. From Oceanus and Tethys came the three thousand river gods (including Nilus [Nile], Alpheus, and Scamander) and three thousand Oceanid nymphs (including Doris, Electra, Callirhoe, Styx, Clymene, Metis, Eurynome, Perseis, and Idyia). From Hyperion and Theia came Helios (Sun), Selene (Moon), and Eos (Dawn), and from Crius and Eurybia came Astraios, Pallas, and Perses. From Eos and Astraios came the winds: Zephyrus, Boreas and Notos, Eosphoros (Dawn-bringer, i.e. Venus, the Morning Star), and the Stars. From Pallas and the Oceanid Styx came Zelus (Envy), Nike (Victory), Kratos (Power), and Bia (Force).[60]

From Coeus and Phoebe came Leto and Asteria, who married Perses, producing Hekate,[61] and from Cronus and his older sister, Rhea, came Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus.[62] The Titan Iapetos married the Oceanid Clymene and produced Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus.[63]

| Descendants of the Titans[64] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Children of Zeus and his seven wives

Zeus married seven wives. His first wife was the Oceanid Metis, whom he impregnated with Athena, then, on the advice of Gaia and Uranus, swallowed Metis so that no son of his by Metis would overthrow him, as had been foretold.[69] Zeus' second wife was his aunt the Titan Themis, who bore the three Horae (Seasons): Eunomia (Order), Dikē (Justice), Eirene (Peace); and the three Moirai (Fates):[70] Clotho (Spinner), Lachesis (Allotter), and Atropos (Unbending). Zeus then married his third wife, another Oceanid, Eurynome, who bore the three Charites (Graces): Aglaea (Splendor), whom Hephaestus married, Euphrosyne (Joy), and Thalia (Good Cheer).[71]

Zeus' fourth wife was his sister, Demeter, who bore Persephone. The fifth wife of Zeus was another aunt, the Titan Mnemosyne, from whom came the nine Muses: Clio, Euterpe, Thalia, Melpomene, Terpsichore, Erato, Polymnia, Urania, and Calliope. His sixth wife was the Titan Leto, who gave birth to Apollo and Artemis. Zeus' seventh and final wife was his sister Hera, the mother by Zeus of Hebe, Ares, and Eileithyia.[72]

Zeus finally "gave birth" himself to Athena, from his head, which angered Hera so much that she produced, by herself, her own son Hephaestus, god of fire and blacksmiths.[73]

| Children of Zeus and his seven wives [74] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other descendants of divine fathers

From Poseidon and the Nereid Amphitrite was born Triton, and from Ares and Aphrodite came Phobos (Fear), Deimos (Terror), and Harmonia (Harmony). Zeus, with Atlas's daughter Maia, produced Hermes, and with the mortal Alcmene, produced the hero Heracles, who married Hebe. Zeus and the mortal Semele, daughter of Harmonia and Cadmus, the founder and first king of Thebes, produced Dionysus, who married Ariadne, daughter of Minos, king of Crete. Helios and the Oceanid Perseis produced Circe, Aeetes, who became king of Colchis and married the Oceanid Idyia, producing Medea.[80]

| Other descendants of divine fathers [81] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Children of divine mothers with mortal fathers

The goddess Demeter joined with the mortal Iasion to produce Plutus. In addition to Semele, the goddess Harmonia and the mortal Cadmus also produced Ino, Agave, Autonoe and Polydorus. Eos (Dawn) with the mortal Tithonus, produced the hero Memnon, and Emathion, and with Cephalus, produced Phaethon. Medea with the mortal Jason, produced Medius, the Nereid Psamathe with the mortal Aeacus, produced the hero Phocus, the Nereid Thetis, with Peleus produced the great warrior Achilles, and the goddess Aphrodite with the mortal Anchises produced the Trojan hero Aeneas. With the hero Odysseus, Circe would give birth to Agrius, Latinus, and Telegonus, and Atlas' daughter Calypso would also bear Odysseus two sons, Nausithoos and Nausinous.[90]

| Children of goddesses with mortals [91] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prometheus

The Theogony, after listing the offspring of the Titan Iapetus and the Oceanid Clymene, as Atlas, Menoitios, Prometheus, and Epimetheus, and telling briefly what happened to each, tells the story of Prometheus.[98] When the gods and men met at Mekone to decide how sacrifices should be distributed, Prometheus sought to trick Zeus. Slaughtering an ox, he took the valuable fat and meat, and covered it with the ox's stomach. Prometheus then took the bones and hid them with a thin glistening layer of fat. Prometheus asked Zeus' opinion on which offering pile he found more desirable, hoping to trick the god into selecting the less desirable portion. Though Zeus saw through the trick, he chose the fat covered bones, and so it was established that ever after men would burn the bones as sacrifice to the gods, keeping the choice meat and fat for themselves. But in punishment for this trick, an angry Zeus decided to deny mankind the use of fire. But Prometheus stole fire inside a fennel stalk, and gave it to humanity. Zeus then ordered the creation of the first woman Pandora as a new punishment for mankind. And Prometheus was chained to a cliff, where an eagle fed on his ever-regenerating liver every day, until eventually Zeus' son Heracles came to free him.

Influence on earliest Greek philosophy

The heritage of Greek mythology already embodied the desire to articulate reality as a whole, and this universalizing impulse was fundamental for the first projects of speculative theorizing. It appears that the order of being was first imaginatively visualized before it was abstractly thought. Hesiod, impressed by necessity governing the ordering of things, discloses a definite pattern in the genesis and appearance of the gods. These ideas made something like cosmological speculation possible. The earliest rhetoric of reflection all centers about two interrelated things: the experience of wonder as a living involvement with the divine order of things; and the absolute conviction that, beyond the totality of things, reality forms a beautiful and harmonious whole.[100]

In the Theogony, the origin (arche) is Chaos, a divine primordial condition, and there are the roots and the ends of the earth, sky, sea, and Tartarus. Pherecydes of Syros (6th century BC), believed that there were three pre-existent divine principles and called the water also Chaos.[101] In the language of the archaic period (8th – 6th century BC), arche (or archai) designates the source, origin, or root of things that exist. If a thing is to be well established or founded, its arche or static point must be secure, and the most secure foundations are those provided by the gods: the indestructible, immutable, and eternal ordering of things.[102]

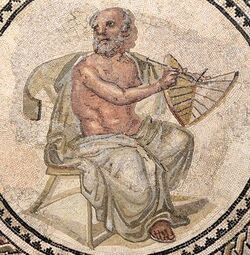

In ancient Greek philosophy, arche is the element or first principle of all things, a permanent nature or substance which is conserved in the generation of the rest of it. From this, all things come to be, and into it they are resolved in a final state.[103] It is the divine horizon of substance that encompasses and rules all things. Thales (7th – 6th century BC), the first Greek philosopher, claimed that the first principle of all things is water. Anaximander (6th century BC) was the first philosopher who used the term arche for that which writers from Aristotle on call the "substratum".[104] Anaximander claimed that the beginning or first principle is an endless mass (Apeiron) subject to neither age nor decay, from which all things are being born and then they are destroyed there. A fragment from Xenophanes (6th century BC) shows the transition from Chaos to Apeiron: "The upper limit of earth borders on air. The lower limit of earth reaches down to the unlimited (i.e the Apeiron)."[105]

Other cosmogonies in ancient literature

In the Theogony the initial state of the universe, or the origin (arche) is Chaos, a gaping void (abyss) considered as a divine primordial condition, from which appeared everything that exists. Then came Gaia (Earth), Tartarus (the cave-like space under the earth; the later-born Erebus is the darkness in this space), and Eros (representing sexual desire - the urge to reproduce - instead of the emotion of love as is the common misconception). Hesiod made an abstraction because his original chaos is something completely indefinite.[106]

By contrast, in the Orphic cosmogony the unaging Chronos produced Aether and Chaos and made a silvery egg in divine Aether. From it appeared the androgynous god Phanes, identified by the Orphics as Eros, who becomes the creator of the world.[107]

Some similar ideas appear in the Vedic and Hindu cosmologies. In the Vedic cosmology the universe is created from nothing by the great heat. Kāma (Desire) the primal seed of spirit, is the link which connected the existent with the non-existent [108] In the Hindu cosmology, in the beginning there was nothing in the universe but only darkness and the divine essence who removed the darkness and created the primordial waters. His seed produced the universal germ (Hiranyagarbha), from which everything else appeared.[109]

In the Babylonian creation story Enûma Eliš the universe was in a formless state and is described as a watery chaos. From it emerged two primary gods, the male Apsu and female Tiamat, and a third deity who is the maker Mummu and his power for the progression of cosmogonic births to begin.[110]

Norse mythology also describes Ginnungagap as the primordial abyss from which sprang the first living creatures, including the giant Ymir whose body eventually became the world, whose blood became the seas, and so on; another version describes the origin of the world as a result of the fiery and cold parts of Hel colliding.

Editions

Selected translations

- Athanassakis, Apostolos N., Theogony; Works and days; Shield / Hesiod; introduction, translation, and notes, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. ISBN:0-8018-2998-4

- Cook, Thomas, "The Works of Hesiod," 1728.

- Frazer, R.M. (Richard McIlwaine), The Poems of Hesiod, Norman : University of Oklahoma Press, 1983. ISBN:0-8061-1837-7

- Most, Glenn, translator, Hesiod, 2 vols., Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006–07.

- Schlegel, Catherine M., and Henry Weinfield, translators, Theogony and Works and Days, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2006

- Johnson, Kimberly, Theogony and Works and Days: A New Critical Edition, Northwestern University Press, 2017. ISBN:081013487X.

See also

- Ancient literature

- Gigantomachy

- Theomachy

- Pherecydes of Syros

Notes

- ↑ θεογονία. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ↑ West 1966, p. 45.

- ↑ Sandwell, Barry (1996). Presocratic Philosophy vol.3. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415101707. https://books.google.com/books?id=k561uXI-uPgC. p. 28

- ↑ Stoddard, Kathryn B. (2003). "The Programmatic Message of the 'Kings and Singers' Passage: Hesiod, Theogony 80-103". Transactions of the American Philological Association 133 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1353/apa.2003.0010.

- ↑ Herodotus (II.53) cited it simply as an authoritative list of divine names, attributes and functions.

- ↑ F. Solmsen, Hesiod and Aeschylus (Ithaca: Cornell Studies in Classical Philology 30) 1949:53 and note 179 with citations; "if an interpolation," Joseph Eddy Fontenrose observes (Python: a study of Delphic myth and its origins: 71, note 3), "it was made early enough."

- ↑ Lambert, Wilfred G.; Walcot, Peter (1965). "A New Babylonian Theogony and Hesiod". Kadmos 4 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1515/kadm.1965.4.1.64.

- ↑ Walter Burkert, The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age (Harvard University Press) 192, offers discussion and bibliography of related questions.

- ↑ Hard, pp. 65–69; West 1966, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Theogony 132–153 (Most, pp. 12, 13).

- ↑ Theogony 154–155 (Most, pp. 14, 15). Exactly which of these eighteen children Hesiod meant that Uranus hated is not entirely clear, all eighteen, or perhaps just the Cyclopes and the Hundred-Handers. Hard, p. 67; West 1988, p. 7, and Caldwell, p. 37 on lines 154–160, make it all eighteen; while Gantz, p. 10, says "likely all eighteen"; and Most, p. 15 n. 8, says "apparently only the ... Cyclopes and Hundred-Handers are meant" and not the twelve Titans. See also West 1966, p. 206 on lines 139–53, p. 213 line 154 γὰρ. Why Uranus hated his children is also not clear. Gantz, p. 10 says: "The reason for [Uranus'] hatred may be [his children's] horrible appearance, though Hesiod does not quite say this"; while Hard, p. 67 says: "Although Hesiod is vague about the cause of his hatred, it would seem that he took a dislike to them because they were terrible to behold". However, West 1966, p. 213 on line 155, says that Uranus hated his children because of their "fearsome nature".

- ↑ Theogony 156–158 (Most, pp. 14, 15). The hiding place inside Gaia is presumably her womb, see West 1966, p. 214 on line 158; Caldwell, p. 37 on lines 154–160; Gantz, p. 10. This place seems also to be the same place as Tartarus, see West 1966, p. 338 on line 618, and Caldwell, p. 37 on lines 154–160.

- ↑ Theogony 159–172 (Most, pp. 16, 17).

- ↑ Theogony 173–182 (Most, pp. 16, 17); according to Gantz, p. 10, Cronus waited in ambush, and reached out to castrate Uranus, from "inside [Gaia's] body, we will understand, if he too is a prisoner".

- ↑ Hard, p. 67; West 1966, p. 19. As Hard notes, in the Theogony apparently, although the Titans were freed as a result of Uranus' castration, the Cyclopes and Hundred-Handers remain imprisoned (see below), see also West 1966, p. 214 on line 158.

- ↑ Theogony 453–467 (Most, pp. 38, 39).

- ↑ Theogony 468–484 (Most, pp. 40, 41). Mount Aigaion is otherwise unknown, and Lyctus is nowhere else associated with Zeus' birth, later tradition located the cave on Mount Ida, or sometimes Mount Dikte, see Hard, pp. 74–75; West 1966, pp. 297–298 on line 477, p. 300 on line 484.

- ↑ Theogony 485–491 (Most, pp. 40, 41).

- ↑ Theogony 492–500 (Most, pp. 42, 43).

- ↑ Theogony 501–506 (Most, pp. 42, 43); Hard, pp. 68–69; West 1966, p. 206 on lines 139–153, pp. 303–305 on lines 501–506. According to Apollodorus, 1.1.4–5, after the overthrow of Uranus, the Cyclopes (as well as the Hundred-Handers) were rescued from Tartarus by the Titans, but reimprisoned by Cronus.

- ↑ Theogony 624–721 (Most, pp. 52, 53). This is the sequence of events understood to be implied in the Theogony by, for example, Hard, p. 68; Caldwell, p. 65 on line 636; and West 1966, p. 19. However according to Gantz, p. 45, "Hesiod's account does not quite say whether the Hundred-Handers were freed before the conflict or only in the tenth year. ... Eventually, if not at the beginning, the Hundred-Handers are fighting".

- ↑ Theogony 820–868 (Most, pp. 68, 69).

- ↑ Theogony 881–885 (Most, pp. 72, 73).

- ↑ Theogony 886–900 (Most, pp. 74, 75).

- ↑ Theogony 116–122 (Most, pp. 12, 13). West 1966, p. 192 line 116 Χάος, "best translated Chasm"; Most, p. 13, translates Χάος as "Chasm", and notes: (n. 7): "Usually translated as 'Chaos'; but that suggests to us, misleadingly, a jumble of disordered matter, whereas Hesiod's term indicates instead a gap or opening". Other translations given in this section follow those given by Caldwell, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Theogony 123–125 (Most, pp. 12, 13).

- ↑ Theogony 126–132 (Most, pp. 12, 13).

- ↑ Theogony 116–132 (Most, pp. 12, 13); Caldwell, p. 5, table 3; Hard, p. 694; Gantz, p. xxvi.

- ↑ Theogony 132–138 (Most, pp. 12, 13).

- ↑ Theogony 139–146 (Most, pp. 14, 15).

- ↑ Theogony 147–153 (Most, pp. 14, 15).

- ↑ Theogony 132–153 (Most, pp. 12, 13); Caldwell, p. 5, table 3.

- ↑ Theogony 173–206 (Most, pp. 16, 17).

- ↑ Theogony 183–200 (Most, pp. 16, 17); Caldwell, p. 6, table 4.

- ↑ At 904 the Moirai are the daughters of Zeus and Themis.

- ↑ Theogony 211–225 (Most, pp. 20, 21). The translations of the names used here are those given by Caldwell, p. 6, table 5.

- ↑ Theogony 226–232 (Most, pp. 20, 21). The translations of the names used here are those given by Caldwell, p. 6, table 5.

- ↑ Theogony 211–232 (Most, pp. 20, 21); Caldwell, pp. 6–7, table 5.

- ↑ At 904 the Moirai are the daughters of Zeus and Themis.

- ↑ Theogony 233–269 (Most, pp. 22, 23).

- ↑ Theogony 270–294 (Most, pp. 24, 25).

- ↑ Theogony 295–305 (Most, pp. 26, 27).

- ↑ The "she" at 295 is ambiguous. While some have read this "she" as referring to Callirhoe, according to Clay, p. 159 n. 32, "the modern scholarly consensus" reads Ceto, see for example Gantz, p. 22; Caldwell, pp. 7, 46 295–303.

- ↑ Theogony 333–336 (Most, pp. 28, 29); Apollonius of Rhodes, 4.1396.

- ↑ Theogony 233–297, 333–335 (Ladon) (Most, pp. 22, 23, 28, 29); Caldwell, p. 7, tables 6–9; Hard, p. 696.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 350.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 349.

- ↑ The fifty sea nymphs, including: Amphitrite ( 243), Thetis ( 244), Galatea ( 250), and Psamathe ( 260).

- ↑ Who Echidna's mother is supposed to be, is unclear, she is probably Ceto, but possibly Callirhoe. The "she" at 295 is ambiguous. While some have read this "she" as referring to Callirhoe, according to Clay, p. 159 n. 32, "the modern scholarly consensus" reads Ceto, see for example Gantz, p. 22; Caldwell, pp. 7, 46 295–303.

- ↑ Unnamed by Hesiod, but described at 334–335 as a terrible serpent who guards the golden apples.

- ↑ Son of Cronus and Rhea at 456, where he is called "Earth-Shaker".

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 351.

- ↑ Theogony 821–822 (Most, pp. 68, 69).

- ↑ Theogony 304–332 (Most, pp. 26, 27).

- ↑ The "she" at 319 is ambiguous, see Clay, p. 159, with n. 34, but probably refers to Echidna, according to Gantz, p. 22; Most, p. 29 n.18; Caldwell, p. 47 on lines 319-325; but possibly the Hydra, or less likely Ceto.

- ↑ The "she" at 326 is ambiguous, see Clay, p. 159, with n. 34, but probably refers to the Chimera according to Gantz, p. 23; Most, p. 29 n. 20; West 1988, p. 67 n. 326; but possibly to Echidna or less likely to Ceto.

- ↑ Theogony 304-327, 821–822 (Typhon) (Most, pp. 26, 27, 68, 69); Caldwell, p. 8, table 10; Hard, p. 696.

- ↑ Who the Chimera's mother is supposed to be, is unclear, she is probably Echidna, but possibly the Hydra.

- ↑ Who Orthrus mates with is unclear, probably the Chimera, but possibly Echidna.

- ↑ Theogony 337–388 (Most, pp. 30, 31). The translations of the names used here follow Caldwell, p. 8.

- ↑ Theogony 404–411 (Most, pp. 34, 35).

- ↑ Theogony 453–458 (Most, pp. 38, 39).

- ↑ Theogony 507–511 (Most, pp. 42, 43).

- ↑ Theogony 337–411, 453–520 (Most, pp. 30, 31, 38, 39); Caldwell, pp. 8–9, tables 11–13; Hard, p. 695.

- ↑ The 3,000 river gods, of which 25 are named: Nilus, Alpheus, Eridanos, Strymon, Maiandros, Istros, Phasis, Rhesus, Achelous, Nessos, Rhodius, Haliacmon, Heptaporus, Granicus, Aesepus, Simoeis, Peneus, Hermus, Caicus, Sangarius, Ladon, Parthenius, Evenus, Aldeskos, Scamander.

- ↑ The 3,000 daughters, of which 41 are named: Peitho, Admete, Ianthe, Electra, Doris, Prymno, Urania, Hippo, Clymene, Rhodea, Callirhoe, Zeuxo, Clytie, Idyia, Pasithoe, Plexaura, Galaxaura, Dione, Melobosis, Thoe, Polydora, Cerceis, Plouto, Perseis, Ianeira, Acaste, Xanthe, Petraea, Menestho, Europa, Metis, Eurynome, Telesto, Chryseis, Asia, Calypso, Eudora, Tyche, Amphirho, Ocyrhoe, and Styx.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 361.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 351.

- ↑ Theogony 886–900 (Most, pp. 74, 75).

- ↑ At 217 the Moirai are the daughters of Nyx.

- ↑ Theogony 901–911. The translations of the names used here, follow Caldwell, p. 11, except for the translations of Aglaea, Euphrosyne and Thalia, which use those given by Most, p. 75.

- ↑ Theogony 912–923 (Most, pp. 74–77).

- ↑ Theogony 924–929 (Most, pp. 76, 77).

- ↑ Theogony 886–929 (Most, pp. 74, 75); Caldwell, p. 11, table 14.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 358.

- ↑ Of Zeus' children by his seven wives, Athena was the first to be conceived ( 889), but the last to be born. Zeus impregnated Metis then swallowed her, later Zeus himself gave birth to Athena "from his head" ( 924).

- ↑ At 217 the Moirai are the daughters of Nyx.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 358.

- ↑ Hephaestus is produced by Hera alone, with no father at 927–929. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, Hephaestus is apparently the son of Hera and Zeus, see Gantz, p. 74.

- ↑ Theogony 930–962 (Most, pp. 76, 77).

- ↑ Theogony 930–962, 975–976 (Most, pp. 76, 77, 80, 81); Caldwell, p. 12, table 15.

- ↑ One of the Nereid daughters of Nereus and Doris, at 243.

- ↑ Called by her title "Cytherea" ("of the Island Cythera") at 934.

- ↑ Cadmus was the mortal founder and first king of Thebes; no parentage is given in the Theogony.

- ↑ At 938 called the "Atlantid" i.e. daughter of Atlas, according to Apollodorus, 3.10.1, she was one of the seven Pleiades, daughters of Atlas and the Oceanid Pleione.

- ↑ Alcmene was the granddaughter of Perseus, and hence the great-granddaughter of Zeus.

- ↑ The daughter of Minos, king of Crete.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 356.

- ↑ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 352.

- ↑ Theogony 963–1018 (Most, pp. 78, 79). According to West 1966, p. 434 on line 1014, the line, which has Circe being the mother of Telegonus, is probably a later (Byzantine?) interpolation.

- ↑ Theogony 969–1018 (Most, pp. 80, 81); Caldwell, p. 12, table 15.

- ↑ According to Apollodorus, 3.12.1, Iasion was the son of Zeus and Electra, one of the seven Pleiades, daughters of Atlas and the Oceanid Pleione.

- ↑ The son of Apollo and Cyrene, Diodorus Siculus, 4.81.1–2, Pausanias, 10.17.3.

- ↑ One of the Nereid daughters of Nereus and Doris, at 260.

- ↑ One of the Nereid daughters of Nereus and Doris, at 245.

- ↑ According to Caldwell, p. 49 on line 359, this Calypso, elsewhere the daughter of Atlas, is "probably not" the same Calypso named at 359 as one of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys; see also West 1966, p. 267 359. καὶ ἱμερόεσσα Καλυψώ; Hard, p. 41.

- ↑ According to West 1966, p. 434 on line 1014, the line, which has Circe being the mother of Telegonus, is probably a later (Byzantine?) interpolation.

- ↑ Theogony 507–616 (Most, pp. 42, 43).

- ↑ Zühmer, T. H. (19 October 2016). "Roman Mosaic Depicting Anaximander with Sundial". New York University. http://isaw.nyu.edu/exhibitions/time-cosmos/objects/roman-mosaic-anaximander.

- ↑ Barry Sandywell (1996). Presocratic Philosophy vol.3. Rootledge New York. p. 28, 42

- ↑ DK B1a

- ↑ Barry Sandwell (1996). Presocratic philosophy vol.3. Rootledge New York. ISBN 9780415101707. p.142

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaph. Α983.b6ff

- ↑ Hippolytus of Rome I.6.I DK B2

- ↑ Karl Popper (1998). The World of Parmenides. Rootledge New York. ISBN 9780415173018. https://books.google.com/books?id=V76PlyggwQkC. p. 39

- ↑ O.Gigon. Der Ursprung der griechischen Philosophie.Von Hesiod bis Parmenides.Bale.Stuttgart.Schwabe & Co. p. 29

- ↑ G. S. Kirk, J. E. Raven and M. Schofield (2003). The Presocratic Philosophers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274555. https://books.google.com/books?id=kFpd86J8PLsC. p. 24

- ↑ "Thereafter rose Desire in the beginning, Desire the primal seed and germ of Spirit, Sages who searched with their heart's thought discovered the existent's kinship in the non-existent." Rig Veda X.129: The Hymns of the Rig Veda, Book X, Hymn CXXIX, Verse 4, p. 575

- ↑ Matsya Purana (2.25.30) – online: "The creation"

- ↑ The Babylonian creation story (Enûma Eliš) –online

References

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, edited and translated by William H. Race, Loeb Classical Library No. 1, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN:978-0-674-99630-4. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Brown, Norman O. Introduction to Hesiod: Theogony (New York: Liberal Arts Press) 1953.

- Caldwell, Richard, Hesiod's Theogony, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company (June 1, 1987). ISBN:978-0-941051-00-2.

- Clay, Jenny Strauss, Hesiod's Cosmos, Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN:978-0-521-82392-0.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN:978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN:978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN:9780415186360.

- Lamberton, Robert, Hesiod, New Haven : Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN:0-300-04068-7. Cf. Chapter II, "The Theogony", pp. 38–104.

- Brill's Companion to Hesiod. Leiden. 2009. doi:10.1163/9789047440758. ISBN 978-90-04-17840-3.

- Script error: No such module "Harvc". doi:10.1163/9789047440758_006

- Script error: No such module "Harvc". doi:10.1163/9789047440758_003

- Most, G.W., Hesiod, Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia, Edited and translated by Glenn W. Most, Loeb Classical Library No. 57, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2018. ISBN:978-0-674-99720-2. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Tandy, David W., and Neale, Walter C. [translators], Works and Days: a translation and commentary for the social sciences, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN:0-520-20383-6

- West, M. L. (1966), Hesiod: Theogony, Oxford University Press. ISBN:0-19-814169-6.

- West, M. L. (1988), Hesiod: Theogony and Works and Days, Oxford University Press. ISBN:978-0-19-953831-7.

- Verdenius, Willem Jacob, A Commentary on Hesiod Works and Days vv 1-382 (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1985). ISBN:90-04-07465-1

External links

- Hesiod, Theogony: text in English translation.

- Hesiod, Theogony e-text in Ancient Greek (from Perseus)

- Hesiod, Theogony e-text in English (from Perseus)

- Script error: No such module "Librivox book".

|

33 views | Status: cached on April 24 2025 18:45:01

↧ Download this article as ZWI file

KSF

KSF