Wisdom literature

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. Although this genre uses techniques of traditional oral storytelling, it was disseminated in written form.

The earliest known wisdom literature dates back to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, originating from ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. These regions continued to produce wisdom literature over the subsequent two and a half millennia. Wisdom literature from Jewish, Greek, Chinese, and Indian cultures started appearing around the middle of the 1st millennium BC. In the 1st millennium AD, Egyptian-Greek wisdom literature emerged, some elements of which were later incorporated into Islamic thought.

Much of wisdom literature can be broadly categorized into two types - conservative "positive wisdom" and critical "negative wisdom" or "vanity literature":[1][2][3][4][5]

- Conservative Positive Wisdom - Pragmatic, real-world advice about proper behavior and actions,[2] attaining success in life,[3][4] living a good and fulfilling life,[4] etc.. Examples of this genre include: Proverbs, The Instructions of Shuruppak, and first part of Sima Milka.[4]

- Critical Negative Wisdom (AKA "Vanity Literature" or "Wisdom in Protest") - A more pessimistic outlook, frequently expressing skepticism about the scope of human achievements, highlighting the inevitability of mortality,[2] advocating the rejection of all material gains,[5] and expressing the carpe diem view that, since nothing has intrinsic value (vanity theme) and all will come to an end (memento mori theme), therefore one should just enjoy life to the fullest while they can (carpe diem theme).[3][4] Examples of this genre include: Qohelet, The Ballad of Early Rulers, Enlil and Namzitarra, the second part of Sima Milka (the son's response),[4] and Nig-Nam Nu-Kal ("Nothing is of Value").[5]

Another common genre is existential works that deal with the relationship between man and God, divine reward and punishment, theodicy, the problem of evil, and why bad things happen to good people. The protagonist is a "just sufferer" - a good person beset by tragedy, who tries to understand his lot in life. The most well known example is the Book of Job, however it was preceded by, and likely based on, earlier Mesopotamian works such as The Babylonian Theodicy (sometimes called The Babylonian Job), Ludlul bēl nēmeqi ("I Will Praise the Lord of Wisdom" or "The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer"), Dialogue between a Man and His God, and the Sumerian Man and His God.[5]

The literary genre of mirrors for princes, which has a long history in Islamic and Western Renaissance literature, is a secular cognate of wisdom literature. In classical antiquity, the didactic poetry of Hesiod, particularly his Works and Days, was regarded as a source of knowledge similar to the wisdom literature of Egypt, Babylonia and Israel.[citation needed] Pre-Islamic poetry is replete with many poems of wisdom, including the poetry of Zuhayr bin Abī Sūlmā (520–609).

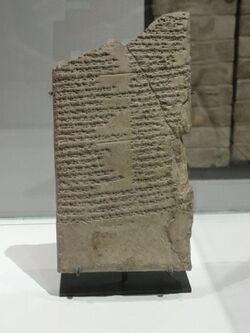

Ancient Mesopotamian literature

The wisdom literature from Sumer and Babylonia is among the most ancient in the world, with the Sumerian documents dating back to the third millennium BC and the Babylonian dating to the second millennium BC. Many of the extant texts uncovered at Nippur are as ancient as the 18th century BC. Most of these texts are wisdom in the form of dialogues or hymns, such as the Hymn to Enlil, the All-Beneficent from ancient Sumer.[6]

Proverbs were particularly popular among the Sumerians, with many fables and anecdotes therein, such as the Debate Between Winter and Summer, which Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer has noted as paralleling the story of Cain and Abel in the Book of Genesis (Genesis 4:1–16)[7] and the form of disputation is similar to that between Job and his friends in the Book of Job (written c. 6th century BC).[8]

My lord, I have reflected within my reins, [...] in [my] heart. I do not know what sin I have committed. Have I [eaten] a very evil forbidden fruit? Does brother look down on brother? — Dialogue between a Man and His God, c. 19th–16th centuries BC[9]

Several other ancient Mesopotamian texts parallel the Book of Job, including the Sumerian Man and his God (remade by the Old Babylonians into Dialogue between a Man and His God, c. 19th–16th centuries BC) and the Akkadian text, The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer;[10] the latter text concerns a man who has been faithful his whole life and yet suffers unjustly until he is ultimately delivered from his afflictions.[11] The ancient poem known as the Babylonian Theodicy from 17th to 10th centuries BC also features a dialogue between a sufferer and his friend on the unrighteousness of the world.[12]

The 5th-century BC Aramaic story Words of Ahikar is full of sayings and proverbs, many similar to local Babylonian and Persian aphorisms as well as passages similar to parts of the Book of Proverbs and others to the deuterocanonical Wisdom of Sirach.[13]

Notable examples

Instructions of Shuruppak[14] (mid-3rd millennium BC, Sumer): The oldest/earliest known wisdom literature,[5][15][1] as well as one of the longest-lived,[5] and most widely disseminated in Mesopotamia.[16] It presents advice from a father (Shuruppak) to his son (Ziusudra) on various aspects of life, from personal conduct to social relations. The Instructions contain precepts that reflect those later included in the Ten Commandments,[17] and other sayings that are reflected in the biblical Book of Proverbs.[14]

The Counsels of Wisdom (AKA "Teachings of the Sages"): A 150 line compilation of Sumerian and Akkadian proverbs that cover a variety of topics, including ethical conduct and wisdom. Specific topics include: what kind of company to keep, conflict avoidance and diffusion, importance of propriety in speech, the reward of personal piety, etc..[18]

The Instructions of Ur-Ninurta (early-2nd millennium BC): Includes two wisdom sections - “the instructions of the god” and “the instructions of the farmer”. The “instructions of the god” recommend proper religious and moral behavior by contrasting the reward of the god‐fearing with the punishment of the disobedient. The “instructions of the farmer” include agricultural advice.[1] The text ends with short expressions of humility and submission.[19][20]

Instructions of Shupe‐Ameli (AKA: "S(h)ima Milka" or "Hear the Advice"): A father provides his son with conservative "Positive Wisdom" (to work with friends, avoid bad company, not desire other men's wives, etc.); however, the son counters with critical "Negative Wisdom" commonly found in the "Vanity Literature" or "Wisdom in Protest" genre of wisdom literature (it is all pointless since you will die).[2][5]

Nig-Nam Nu-Kal ("Nothing is of Value"): A number of short Sumerian that celebrate life with the repeated refrain "Nothing is of worth, but life itself is sweet".[5]

Ancient Egyptian literature

In ancient Egyptian literature, wisdom literature belonged to the sebayt ("teaching") genre which flourished during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt and became canonical during the New Kingdom. Notable works of this genre include the Instructions of Kagemni, The Maxims of Ptahhotep, the Instructions of Amenemhat, the Loyalist Teaching. Hymns such as A Prayer to Re-Har-akhti (c. 1230 BC) feature the confession of sins and appeal for mercy:

Do not punish me for my numerous sins, [for] I am one who knows not his own self, I am a man without sense. I spend the day following after my [own] mouth, like a cow after grass.[21]

Much of the surviving wisdom literature of ancient Egypt was concerned with the afterlife. Some of these take the form of dialogues, such as The Debate Between a Man and his Soul from 20th–18th centuries BC, which features a man from the Middle Kingdom lamenting about life as he speaks with his ba.[22] Other texts display a variety of views concerning life after death, including the rationalist skeptical The Immortality of Writers and the Harper's Songs, the latter of which oscillates between hopeful confidence and reasonable doubt.[23]

Hermetic tradition

The Corpus Hermeticum is a piece of Egyptian-Greek wisdom literature in the form of a dialogue between Hermes Trismegistus and a disciple. The majority of the text date to the 1st–4th century AD, though the original materials the texts may be older;[24] recent scholarship confirms that the syncretic nature of Hermeticism arose during the times of Roman Egypt, but the contents of the tradition parallel the older wisdom literature of Ancient Egypt, suggesting origins during the Pharaonic Age.[25][26] The Hermetic texts of the Egyptians mostly dealt with summoning spirits, animating statues, Babylonian astrology, and the then-new practice of alchemy; additional mystical subjects include divine oneness, purification of the soul, and rebirth through the enlightenment of the mind.[27]

Islamic Hermeticism

The wisdom literature of Egyptian Hermeticism ended up as part of Islamic tradition, with his writings considered by the Abbasids as sacred inheritance from the Prophets and Hermes himself as the ancestor of the Prophet Muhammad. In the version of the Hermetic texts kept by the Ikhwan al-Safa, Hermes Trismegistus is identified as the ancient prophet Idris; according to their tradition, Idris traveled from Egypt into heaven and Eden, bringing the Black Stone back to earth when he landed in India .[28] The star-worshipping sect known as the Sabians of Harran also believed that their doctrine descended from Hermes Trismegistus.[29]

Biblical wisdom literature and Jewish texts

The most famous examples of wisdom literature are found in the Bible.[30][31] Wisdom[lower-alpha 1] is a central topic in the Sapiential Books [lower-alpha 2], i.e., Proverbs, Psalms, Job, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Book of Wisdom, Wisdom of Sirach, and to some extent Baruch. Not all the Psalms are usually regarded as belonging to the Wisdom tradition.[34] Others such as Epistle of Aristeas, Pseudo-Phocylides and 4 Maccabees are also considered sapiential.

The later Sayings of the Fathers, or Pirkei Avot in the Talmud follows in the tradition of wisdom literature, focusing more on Torah study as a means for achieving a reward, rather than studying wisdom for its own sake.[35]

Other traditions

- Works and Days by Hesiod (c. 750–650 BC) and Hávamál from Old Norse texts (c. 1200) have both been analyzed in terms of the oral transmission of wisdom literature to other cultures.[36]

- Subhashita , a genre of Sanskrit literature is another predominant form of wisdom poetry. Several thousands verses covering wide range of ethics and righteousness have been written and compiled in anthologies called Subhashitani by various authors through ancient and mediaeval period in India.[37]

See also

- Apophthegmata Patrum

- Conduct book

- Dialogue of Pessimism

- Ludlul bēl nēmeqi

- Eastern philosophy

- Nasîhat

- Musar literature

- Proverb

- Sage writing

- Sebayt

- Self-help

- Teaching stories

- The Triads of Ireland, and the Welsh Triads

- Sophia (wisdom)

- Sophia (Gnosticism)

- Wisdom (personification)

Notes

- ↑ The Greek noun sophia (σοφῐ́ᾱ, sophíā) is the translation of "wisdom" in the Greek Septuagint for Hebrew Ḥokmot (חכמות, khakhamút)

- ↑ In Judaism, the Books of Wisdom other than the Wisdom of Solomon and Sirach are regarded as part of the Ketuvim or "Writings", while Wisdom of Solomon and Sirach are not considered part of the biblical canon. Similarly, in Christianity, Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes are included in the Old Testament by all traditions, while Wisdom and Sirach are regarded in some traditions as deuterocanonical works which are placed in the Apocrypha within the Lutheran and Anglican Bible translations.[32][33]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Samet, Nili (2020). "Mesopotamian Wisdom". The Wiley Blackwell companion to wisdom literature. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 328–348. ISBN 9781119158257. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349028589.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Clarke, Michael (2019). Achilles Beside Gilgamesh: Mortality and Wisdom in Early Epic Poetry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-108-48178-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=tG3CDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA55.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hilber, John W. (2019). Boda, Mark J.; Meek, Russell L.; Osborne, William R.. eds. Riddles and Revelations: Explorations into the Relationship between Wisdom and Prophecy in the Hebrew Bible. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-67165-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=k4hoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Cohen, Yoram (2013). Wisdom from the Late Bronze Age. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-754-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=VTVXAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA14.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Cohen, Yoram; Wasserman, Nathan (2021). "Mesopotamian Wisdom Literature". in Kynes, Will. The Oxford Handbook of Wisdom and the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 125–131. ISBN 978-0-19-066128-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=JHAWEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA126.

- ↑ Bullock, C. Hassell (2007). An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books. Moody Publishers. ISBN 978-1575674506. https://books.google.com/books?id=QSGZbt7isfQC.

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer (1961). Sumerian mythology: a study of spiritual and literary achievement in the third millennium B.C.. Forgotten Books. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1605060491. https://books.google.com/books?id=t16tDOHZLLEC&pg=PA72. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ↑ Leo G. Perdue (1991). Wisdom in revolt: metaphorical theology in the Book of Job. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-1850752837. https://books.google.com/books?id=d_KDSNlwvRYC&pg=PA79. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "A Dialogue Between a Man and His God [CDLI Wiki"]. http://cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=dialogue_between_a_man_and_his_god.

- ↑ Hartley, John E. (1988). The Book of Job. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802825285. https://books.google.com/books?id=f-m5GnRjDckC.

- ↑ John L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible, Simon & Schuster, 1965 p. 440.

- ↑ John Gwyn Griffiths (1991). The Divine Verdict: A Study of Divine Judgement in the Ancient Religions. Brill. ISBN 9004092315. https://books.google.com/books?id=QDbjjKglE1kC&q=Babylonian+Theodicy&pg=PA35.

- ↑ W. C. Kaiser, Kr., 'Ahikar uh-hi’kahr', in The Zondervan Encyclopedia of the Bible, ed. by Merrill C. Tenney, rev. edn by Moisés Silva, 5 vols (Zondervan, 2009), s.v.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "The Instructions of Shuruppag: Translation". Oxford University. https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section5/tr561.htm.

- ↑ Samet, Nili (4 May 2023). "Instructions of Shuruppak: The World’s Oldest Instruction Collection". in Cogan, Mordechai; Dell, Katharine J.; Glatt-Gilad, David A.. Human Interaction with the Natural World in Wisdom Literature and Beyond: Essays in Honour of Tova L. Forti. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 216–229. ISBN 978-0-567-70121-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=CT6yEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA216.

- ↑ Dell, Katherine J.; Millar, Suzanna R.; Keefer, Arthur Jan (9 June 2022). The Cambridge Companion to Biblical Wisdom Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-66581-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=mNx0EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA348.

- ↑ The Schoyen Collection website notes, from a Neo-Sumerian tablet of ca. 1900–1700 BCE: line 50: Do not curse with powerful means (3rd Commandment); line 28: Do not kill (6th Commandment); lines 33–34: Do not laugh with or sit alone in a chamber with a girl that is married (7th Commandment); lines 28–31: Do not steal or commit robbery (8th Commandment); and line 36: Do not spit out lies (9th Commandment).

- ↑ Lenzi, Alan (10 January 2020). An Introduction to Akkadian Literature: Contexts and Content. Penn State University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-64602-032-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=cpmYEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA180.

- ↑ Radner, Karen; Moeller, Nadine; Potts, Daniel T. (2022). The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: From the end of the third millennium BC to the fall of Babylon. Oxford University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-19-068757-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=qMBqEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA226.

- ↑ Dell, Katherine J.; Millar, Suzanna R.; Keefer, Arthur Jan (2022). The Cambridge Companion to Biblical Wisdom Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-48316-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=wbhtEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA377.

- ↑ Bullock, C. Hassell (2007). An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books. Moody Publishers. ISBN 978-1575674506. https://books.google.com/books?id=QSGZbt7isfQC.

- ↑ James P. Allen, The Debate between a Man and His Soul: A Masterpiece of Ancient Egyptian Literature Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-9004193031

- ↑ "Ancient Egyptian Literature Volume 1: The Old and Middle Kingdom", Miriam Lichtheim,University of California, 1975, ISBN 0520028996

- ↑ Copenhaver, Brian P. (1995). "Introduction" (in en). Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521425438. https://books.google.com/books?id=OVZP6b9cqLkC. "Scholars generally locate the theoretical Hermetica, 100 to 300 CE; most would put C.H. I toward the beginning of that time. [...] [I]t should be noted that Jean-Pierre Mahe accepts a second-century limit only for the individual texts as they stand, pointing out that the materials on which they are based may come from the first century CE or even earlier. [...] To find theoretical Hermetic writings in Egypt, in Coptic [...] was a stunning challenge to the older view, whose major champion was Father Festugiere, that the Hermetica could be entirely understood in a post-Platonic Greek context."

- ↑ Fowden, Garth, The Egyptian Hermes : a historical approach to the late pagan mind (Cambridge/New York : Cambridge University Press), 1986

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Mahé, "Preliminary Remarks on the Demotic "Book of Thoth" and the Greek Hermetica" Vigiliae Christianae 50.4 (1996:353–363) pp. 358f.

- ↑ "Stages of Ascension in Hermetic Rebirth". Esoteric.msu.edu. http://www.esoteric.msu.edu/Merkur.html.

- ↑ Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis, p. 46. Wheeler, Brannon. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2002

- ↑ Stapleton, Henry E.; Azo, R.F.; Hidayat Husain, M. (1927). "Chemistry in Iraq and Persia in the Tenth Century A.D.". Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal VIII (6): 317–418. OCLC 706947607. http://www.southasiaarchive.com/Content/sarf.100203/231270. pp. 398–403.

- ↑ Crenshaw, James L. "The Wisdom Literature", in Knight, Douglas A. and Tucker, Gene M. (eds), The Hebrew Bible and Its Modern Interpreters (1985).

- ↑ Anderson, Bernhard W. (1967). "The Beginning of Wisdom – Israels Wisdom literature". The Living World of the Old Testament. Longmans. pp. 570ff. ISBN 978-0582489080. https://books.google.com/books?id=X2sOAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Template:Wwbible

- ↑ Geisler, Norman L.; MacKenzie, Ralph E. (1995) (in English). Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences. Baker Publishing Group. p. 171. ISBN 978-0801038754. "Lutherans and Anglicans used it only for ethical / devotional matters but did not consider it authoritative in matters of faith."

- ↑ Estes, Daniel J. (2005). Handbook on the Wisdom Books and Psalms. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. p. 190-192. ISBN 978-0-8010-2699-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=H4ARZdgdyAMC&pg=PA190.

- ↑ Adams, Samuel L.; Goff, Matthew (2020) (in en). Wiley Blackwell Companion to Wisdom Literature. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 369–371. ISBN 978-1119158271. https://books.google.com/books?id=1lbSDwAAQBAJ. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ Canevaro, Lilah Grace (2014). "Hesiod and Hávamál: Transitions and the Transmission of Wisdom". Oral Tradition 29 (1): 99–126. doi:10.1353/ort.2014.0003. ISSN 1542-4308. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/576695/summary. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ Narayan Ram Acharya (in Sanskrit). Subhashita Ratna Bhandagara. sanskritebooks.org/. http://archive.org/details/SubhashitaRatnaBhandagara.

Further reading

- Crenshaw, James L. (2010). Old Testament Wisdom: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664234591.

- Murphy, R. E. (2002). The Tree of Life: An Exploration of Biblical Wisdom Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0802839657.

- Hempel, C.; Lange, A.; Lichtenberger, H. (2002). The Wisdom Texts from Qumran and the Development of Sapiential Thought. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum theologicarum Lovaniensium. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1010-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=FeV0XQR9gCEC.

External links

|

KSF

KSF