Zabaniyya

Topic: Religion

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

In Islam the Zabaniyah (Arabic: الزبانية) (also spelled Zebani) are the forces of hell,[1] who torment the sinners, also called the Angels of punishment or Guardians of Hell.[2] They are often identified with the Nineteen Angels of Hell mentioned in Quran 66:6 and 74:30 or as their subordinates.[3][4] Namely they appear in Surah 96:18. Traditionally they are contrasted with the angels of mercy by their creation from fire instead of light.[5][6] Some scholars regard them, nevertheless, as created from light, along with other angels.[7]

Etymology

The word Zabaniyah may have been derived from the syriac shabbāyā, used to describe angels who conduct the souls of the dead or as frightening demons. Another suggestion attributes the origin to rabbāniyya referring to the lords angelic council.[8] Further Zabaniyah may refer to a class of Arabian demons.[9] According to a recent etymological suggestion, this term may derived from Sumerian zi.ba.an.na ("The Scales") and Assyrian zibanitu meaning scales. On the other hand, nineteen Zabaniyah also originated from astrological map. In ancient concept, the seven planets and twelve astral houses together corresponded to the number nineteen.[10] Al-Mubarrad suggested, zabāniya could derive from the idea of movement and the Zabaniyah are those who "push somebody [back]".[11]

In Islamic traditions

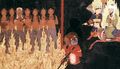

In Miraj literature, one of the Zabaniyya called Susāʾīl, is ordered to show Muhammad the punishments of hell.[12] Islamic art commonly pictures them as horrifying demons with flames leaping from their mouth.[13]

As part of Ismaili eschatology, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi identified the Zabaniyya with the seven planets, who administrate the upper Barzakhs, indicating that there is a kind of hell within the celestrial spheres. Accordingly, impure souls remain emprisioned within bodies, missing salvation in purely intellectual existence. The Houris appear as counterparts of the Zabaniyya, who are, in contrast to the Zabaniyya, items of knowledge from the beyond.[14]

During the post-quranic-exegesis, Zabaniyah were also identified with the angels of death appearing to the unjust[15] assisting Azrail, who conduct the sinners at the moment of death, and seize their souls, appearing as black shadows.[16]

In Non-Islamic traditions

Prior to the anglification of the Zabaniyah, they were probably thought as a kind of demon.[17] Al-Mubarrad relates them to Afarit, a type of underworld demon still prevailing in later Islamic thought. He states that Afarit are sometimes referred to as "ʿifriyya zibniyya", "ZBN" denoting "pushing back" as their characteristic action.[18]

In Turkic lore they are used for hellhounds or hellbound demons,[19] who dwell in the underworld to torture the sinners.[20] Some traditions hold, that they sometimes engage in war against the angels of mercy. If they meet each other, their strikings can cause thunder.[21]

Gallery

See also

- Archon

- Dumah (angel)

- Destroying angel (Bible)

- Kushiel

- Maalik

References

- ↑ Hans Wilhelm Haussig, Egidius Schmalzriedt Wörterbuch der Mythologie Klett-Cotta 1965 ISBN:978-3-129-09870-7 page 314 (german)

- ↑ Stephen Burge Angels in Islam: Jalal Al-Din Al-Suyuti's Al-Haba'ik Fi Akhbar Al-mala'ik Routledge 2015 ISBN:978-1-136-50474-7 page 277

- ↑ Mohammed Rustom The Triumph of Mercy: Philosophy and Scripture in Mulla Sadra SUNY Press 2012 ISBN:9781438443416 p. 90

- ↑ Hajjah Amina Adil Muhammad the Messenger of Islam: His Life & Prophecy BookBaby 2012 ISBN:978-1-618-42913-1

- ↑ Jane Dammen McAuliffe Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān Brill 2001 ISBN:9789004147645 p. 118

- ↑ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb The Encyclopaedia of Islam: NED-SAM Brill 1995 page 94

- ↑ http://www.namazsitesi.com/melekler/zebaniler.html

- ↑ Christian Lange Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions Cambridge University Press 2015 ISBN:978-1-316-41205-3 page 65

- ↑ Christian Lange Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions Cambridge University Press 2015 ISBN:978-1-316-41205-3 page 52

- ↑ Gürdal Aksoy, On the Astrological Background and the Cultural Origins of An Islamic Belie: The Strange Adventures of Munkar and Nakir from the Mesopotamian god Nergal to the Zoroastrian Divinities, https://www.academia.edu/35372440/On_the_Astrological_Background_and_the_Cultural_Origins_of_An_Islamic_Belief_The_Strange_Adventures_of_Munkar_and_Nakir_from_the_Mesopotamian_god_Nergal_to_the_Zoroastrian_Divinities_Mezopotamyal%C4%B1_Tanr%C4%B1_Nergal_den_Zerd%C3%BC%C5%9Fti_Kutsiyetlere_M%C3%BCnker_ile_Nekir_in_Garip_Maceralar%C4%B1_

- ↑ Lange, Christian. “Revisiting Hell’s Angels in the Quran.” Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions edited by Christian Lange, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2016, p. 82 JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.10.

- ↑ ange, Christian. “Revisiting Hell’s Angels in the Quran.” Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions edited by Christian Lange, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2016, p. 139 JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.10

- ↑ Sheila Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800 Yale University Press 1995 ISBN:978-0-300-06465-0 page 62

- ↑ Christian Lange Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions Cambridge University Press 2015 ISBN:9781316412053 p. 214

- ↑ MONA ZAKI JAHANNAM IN MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC THOUGHT 2015 p. 205 ff.

- ↑ ange, Christian. “Revisiting Hell’s Angels in the Quran.” Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions edited by Christian Lange, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2016, p. 74, 94 JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.10

- ↑ Lange, Christian. “Revisiting Hell’s Angels in the Quran.” Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions edited by Christian Lange, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2016, p. 79 JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.10.

- ↑ Lange, Christian. “Revisiting Hell’s Angels in the Quran.” Locating Hell in Islamic Traditions edited by Christian Lange, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2016, p. 82 JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h1w3.10.

- ↑ https://www.almaany.com/en/dict/en-tr/zebani/

- ↑ Bayram Erdoğan Sorularla Türk mitolojisi Pozitif, 2007 ISBN:9789756461471 p. 116

- ↑ Hans Wilhelm Haussig, Egidius Schmalzriedt Wörterbuch der Mythologie Klett-Cotta 1965 ISBN:978-3-129-09870-7 page 314 (german)

KSF

KSF