Anglo-Saxon law

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

Anglo-Saxon law (Old English: ǣ, later lagu 'law'; dōm 'decree', 'judgement') was the legal system of Anglo-Saxon England from the 6th century until the Norman Conquest of 1066. It was a form of Germanic law based on unwritten custom known as folk-right and on written laws enacted by kings with the advice of their witan or council. By the later Anglo-Saxon period, a system of courts had developed to administer the law, while enforcement was the responsibility of ealdormen and royal officials such as sheriffs, in addition to self-policing (friborh) by local communities.

Originally, each Anglo-Saxon kingdom had its own laws. As a result of Viking invasions and settlement, the Danelaw followed Scandinavian laws. In the 10th century, a unified Kingdom of England was created with a single Anglo-Saxon government; however, different regions continued to follow their customary legal systems. The last Anglo-Saxon law codes were enacted in the early 11th century during the reign of Cnut the Great.

Development

Before Christianisation

The native inhabitants of England were Celtic Britons. The unwritten Celtic law was learned and preserved by the Druids, who in addition to their religious role also acted as judges. After the Roman conquest of Britain in the first century, Roman law was operative at least concerning Roman citizens. But the Roman legal system disappeared after the Romans left the island in the 5th century.[1]

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the Anglo-Saxons migrated from continental Europe and established several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. These had their own legal traditions based in Germanic law that "owed little if anything" to Celtic or Roman influences.[2] Anglo-Saxon law largely derived from unwritten customs termed folk-right (Old English: folcriht, 'right or justice of the people').[3]

The older law of real property, of succession, of contracts, the customary tariffs of fines, were mainly regulated by folk-right. Customary law differed between local cultures. There were different folk-rights of West and East Saxons, of East Angles, of Kentish men, Mercians, Northumbrians, Danes, Welshmen, and these main folk-right divisions remained even when tribal kingdoms disappeared and the people were concentrated in one kingdom.[4]

After Christianisation

Following the Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxons, written law codes or "dooms" were produced.[5] The Christian clergy brought with them the art of letters, writing, and literacy.[6] The oldest Anglo-Saxon law codes, especially from Kent and Wessex, reveal a close affinity to Germanic law.[2] The first written Anglo-Saxon laws were issued around 600 by Æthelberht of Kent. Writing in the 8th century, the Venerable Bede comments that Æthelberht created his law code "after the examples of the Romans" (Latin: iuxta exempla Romanorum).[7] This likely refers to Romanised peoples such as the Franks, whose Salic law was codified under Clovis I. As a newly Christian king, Æthelberht's creation of his own law code symbolised his belonging to the Roman and Christian traditions. The actual legislation, however, was not influenced by Roman law. Rather, it converted older customs into written legislation, and, reflecting the role of the bishops in drafting it, protected the English church. The first seven clauses deal solely with compensation for the church.[8]

Folk-right could be broken or modified by special law or special grant, and the fountain of such privileges was the royal power. Alterations and exceptions were, as a matter of fact, suggested by the interested parties themselves, and chiefly by the church. Thus a privileged land-tenure was created—bookland; the rules as to the succession of kinsmen were set at nought by concession of testamentary power and confirmations of grants and wills; special exemptions from the jurisdiction of the hundreds and special privileges as to levying fines were conferred. In process of time the rights originating in royal grants of privilege overbalanced, as it were, folk-right in many respects, and became themselves the starting-point of a new legal system—the feudal one.[4]

In the 9th century, the Danelaw was conquered by Danes and governed under Scandinavian law. The word law itself derives from the Old Norse word laga. Starting with Alfred the Great (r. 871–899), the kings of Wessex united the other Anglo-Saxon peoples against their common Danish enemy. In the process, they created a single Kingdom of England. This unification process was completed under Æthelstan (r. 924–939).[9]

There is a good deal of resemblance between the capitularies legislation of Charlemagne and his successors on one hand and the acts of Alfred, Edward the Elder, Æthelstan and Edgar on the other, a resemblance called forth less by direct borrowing of Frankish institutions than by the similarity of political problems and condition.[4]

The Norman Conquest of 1066 ended the Anglo-Saxon monarchy. But Anglo-Saxon law and institutions survived and formed the foundation for the common law.[10]

Legislation

While custom was respected, kings could adapt the laws of their predecessors and also create new laws.[11] Royal law codes were produced in consultation with the witan, the king's council comprising the lay and ecclesiastical nobility.[12] Some law codes portrayed the witan as initiating new legislation and the king assenting to it. For example, one code begins, "these are the ordinances which the wise men established at Exeter, by the counsel of King Æthelstan".[13] Royal law codes were written to address specific situations and were intended to be read by people who were already familiar with the law.[6]

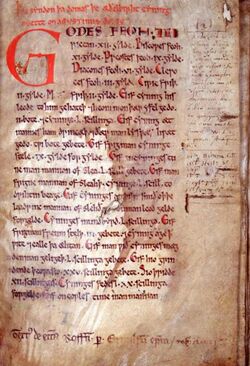

The first law code was the Law of Æthelberht (c. 602), which put into writing the unwritten legal customs of Kent. This was followed by two later Kentish law codes, the Law of Hlothhere and Eadric (c. 673 – c. 685) and the Law of Wihtred (695). Outside of Kent, Ine of Wessex issued a law code between 688 and 694. Offa of Mercia (r. 757–796) produced a law code that has not survived. Alfred the Great, king of Wessex, produced a law code c. 890 known as the Doom Book.[14] The prologue of Alfred's code states that the Bible and penitentials were studied as part of creating his code. In addition, older law codes were studied, including the laws of Æthelberht, Ine, and Offa. This may have been the first attempt to create a limited set of uniform laws across England, and it set a precedent for future English kings.[9]

The House of Wessex became rulers of all England in the 10th century, and their laws were applied throughout the kingdom. Significant 10th-century law codes were promulgated by Edward the Elder, Æthelstan, Edmund I, Edgar, and Æthelred the Unready.[15] But regional variations in laws and customs survived as well. The Domesday Book of 1086 noted that distinct laws existed for Wessex, Mercia, and the Danelaw.[16]

The law codes of Cnut (r. 1016–1035) were the last to be promulgated in the Anglo-Saxon period and are primarily a collection of earlier laws.[15] They became the main source for old English law after the Norman Conquest. For political reasons, these laws were attributed to Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066), and "under the guise of the Leges Edwardi Confessoris they achieved an almost mystical authority which inspired Magna Carta in 1215 and were for centuries embedded in the coronation oath."[17] The Leges Edwardi Confessoris is the best known of the custumals, compilations of Anglo-Saxon customs written after the Conquest to explain Anglo-Saxon laws to the new Norman rulers.[15]

Language and dialect

The English dialect in which the Anglo-Saxon laws have been handed down is in most cases a common speech derived from the West Saxon dialect. Wessex formed the core of the unified Kingdom of England, and the royal court at Winchester became the main literary centre. Traces of the Kentish dialect can be detected in the Textus Roffensis, a manuscript containing the earliest Kentish laws. Northumbrian dialectical peculiarities are also noticeable in some codes, while Danish words occur as technical terms in some documents. With the Norman Conquest, Latin took the place of English as the language of legislation.[18]

Courts

The Anglo-Saxons developed a sophisticated system of assemblies or moots (the Old English words mot and gemot mean "meeting").[19] Historians often call these assemblies courts; however, they were not like the specialised law courts that developed under Angevin government. These assemblies performed a variety of functions beyond judicial business. They issued legislation, organised and performed law enforcement, and witnessed transactions.[20]

Vague references to courts appear in earlier laws. These texts use terms such as folcegemot ('public court or meeting'). Later laws use more specific terminology. The laws of Edgar (r. 959–975) outline a precise division of courts. The hundred court was to meet every four weeks. The borough court was to meet three times a year, and the shire court was to meet twice a year.[21]

King's court

In addition to being a legislator, the king was also a judge.[22] The king heard cases in the presence of his witan or council.[23] Kings could also hear and act on complaints alone, outside of a formal judicial context. The cases heard by the king included:[24]

- matters directly involving the king or royal property

- treason

- land disputes

- appeals from the decisions of lower courts

The law reserved some cases to the king's jurisdiction. In the laws of Cnut, they include:[25][26]

- mundbryce (breach of the king's protection)

- hamsocn (assault on a person inside a house)

- forsteal (assault on a royal road)

- fyrdwite (fine for failing to perform military service)

- In the Danelaw: fihtwite (fine for fighting) and grithbryce (infringement of the peace)

These reserved cases could only be tried in the presence of the king or a royal official, and the fines were paid into the royal treasury. The requirement that a royal official preside usually meant that these cases, if not heard directly by the king, were heard in the shire court.[27]

Shire courts

The shire court was a royal court presided over by the ealdorman and local bishop as royal representatives. The sheriff might also be there, either alongside the ealdorman or in his stead.[29] It met twice a year around Easter and Michaelmas.[30] A law of Cnut allowed it to meet more often if necessary.[31]

While the ealdorman and bishop presided over the court, they were not judges in the modern sense. Decisions were made by the local thegns (nobles) who attended the court as suitors (those who declared the law and made judgements).[30][32] Litigants and their supporters (such as oath-helpers) would also be present.[31]

The shire court likely addressed the most serious crimes, such as death penalty cases. The shire was also the most likely setting for cases reserved to the king . The shire court witnessed land purchases, and it also adjudicated land disputes.[29]

Hundred courts

Most people experienced the judicial system through their local hundred or wapentake.[26] The hundred court met monthly and was presided over by a royal reeve.[33] The laws of Edward the Elder and Æthelstan required reeves to ensure everyone received the benefits of folk-right and royal law.[34]

The hundred had a role in witnessing transactions. Edgar's law required all sales and purchases (such as land, cattle, and the manumission of slaves) to be witnessed by 12 men chosen by the hundred.[35] The hundred handled criminal cases, civil cases, land disputes, and tort.[36] It heard accusations of theft not involving the death penalty and may have executed thieves caught in the act; however, most serious offences were reserved to the shire court's jurisdiction.[35] The hundred handled most ecclesiastical cases (such as tithe and marriage cases),[37] and the bishop or his representative was expected to attend.[36]

Each hundred was responsible for policing itself through a system called friborh ('peace-pledge'). Free men were organised into groups of 10 or 12 called tithings. They pledged to be law abiding and to report crimes on pain of amercement. When a crime was committed, the victim or witnesses could raise the "hue and cry", requiring all able-bodied men to pursue the suspect.[38] The Hundred Ordinance attributed to Edgar commands, "if the need is pressing, the man in charge of the hundred is to be told, and he then is to tell the men in charge of the tithings; and all are to go forth, where God guides them, that they may reach [the thief]. Justice is to be done on the thief as Edmund decreed previously."[39] Suspects who escaped were declared outlaws, and it was said that they "wore the wolf's head", meaning they could be hunted and killed like wolves.[40]

The identities of suitors to the hundred court are unclear. Cnut's law required all freemen 12 years and older to belong to a hundred and tithing. However, this law referred to peacekeeping, and it is unknown if all free men would have attended the hundred court.[41] It is possible that local thegns (or their bailiffs) controlled the court and made its decisions.[42]

Decisions of a hundred court could be appealed to the shire or to the king. Before distraining property, Cnut's law required a man to seek justice three times in the hundred court and, failing that, to appeal to the shire court. Other laws required plaintiffs to seek justice in hundred courts before appealing to the king.[43]

Borough courts

Boroughs were separate from the hundreds and had their own courts (variously termed burghmoot, portmanmoot, or husting).[3] These met three times a year.[33] Like hundreds, boroughs were required to appoint official witnesses for all transactions, 36 witnesses for large boroughs and 12 witnesses for small ones.[35] While initially a regular court, the borough court developed into a special court for the law merchant.[44]

Franchisal courts

The king could grant judicial rights and powers to a lord over his lands or over entire hundreds. It was common for royal writs granting such rights to include the phrases "sake and soke" and "sake and soke, toll and team, and infangentheof."[45]

- Sake and soke: right to hold a court with similar jurisdiction to a hundred court and to collect judicial fines.[46]

- Toll: right to charge tolls.[45]

- Team: right to judge whether goods were acquired in good faith and to collect fines from offenders.[45]

- Infangentheof: right to summary trial and execution of thieves caught in the act.[45]

Sometimes further rights were granted, such as jurisdiction over mundbryce (breach of the king's protection), hamsocn (assault on a person inside a house), and forsteal (assault on a royal road).[45] The king could revoke all of these grants.[47]

Church courts

Synods dealt with legal disputes. Initially, synods may have had jurisdiction over cases involving bookland since this form of land tenure originated within the church.[48]

The king could also grant the church (either the bishop of a diocese or the abbot of a religious house) the right to administer a hundred. The hundred's reeve would then answer to the bishop or abbot. The same cases would be tried as before, but the profits of justice would now go to the church.[49] One such hundred was the Soke of Peterborough.

Trial procedure

While common legal procedures existed, they can be difficult to reconstruct due to lack of evidence and variation in local custom. Shires possessed their own local traditions, and the Danelaw deviated in important ways from other parts of England.[50]

Accusation and denial

Legal proceedings began with an accusation by an aggrieved party. In addition, tithing groups could present accusations as part of the system of friborh .[37] In cases involving royal rights, accusations could be brought by royal officials.[51]

There were two types of cases that could be brought to court. In the first kind, a party claimed they or, in the case of homicide, a relative had been wronged. In the second kind, a claimant asserted that another party was in possession of movable or immovable property rightfully belonging to the claimant. The outcome sought could vary based on the type of case. Claimants might seek restoration of property, compensation, or the offender's punishment.[52]

The initiating party formally stated his charge with a fore-oath. An example formula in the anonymous text Swerian states, "by the Lord, I accuse N. neither for hatred nor for calumny nor for unjust gain; nor do I know anything more true, except as my informant told me and I myself truly relate that he was the thief of my cattle".[53] If strong evidence existed, the accuser would not need to make a fore-oath. However, false accusations were severely punished; the offender would lose his tongue unless he redeemed himself by paying his wergeld.[54]

The defendant had to appear in court at the scheduled time or provide an essoin (excuse) for not attending.[55] Surety (Old English: borh) could be required to ensure the accused attended court and did not attempt to flee justice. This could take the form of a financial pledge, but it also included people standing as pledges. If the accused could find no people to stand surety and had no property to pledge, then he would be imprisoned. The man's kinsmen or lord had a particular responsibility to act as surety for him. If a man fled justice, his surety had to pay his wergeld to the king or to the entitled party.[56]

The accused had to formally deny the accusation in person; however, women and the mute or deaf needed a representative. The denial took the form of an oath, such as "by the Lord, I am guiltless, both in deed and counsel, of the accusation of which N. accuses me".[57]

Argument and mesne judgement

After the initial accusation and denial, the parties themselves (or their supporters) were able to argue their case. Each side told their version of the facts of the case, which could be supported by witnesses or written evidence (such as the well-known Fonthill Letter). Arguments could also cite folk-right or legal norms.[58]

Following the arguments, the court might issue a mesne or intermediate judgement. A mesne judgement might declare the form of proof to be used in the trial and which party should provide that proof. Alternatively, a mesne judgement could appoint a smaller group of people to decide a case.[59]

Proof

Evidence

Witnesses were an important form of evidence, especially in cases involving property. The parties might bring their own witnesses, but the official presiding over the court might also search for witnesses.[60] Charters and other documents could help decide land disputes.[40] Physical evidence could also be utilised. The Fonthill Letter recounts that a cattle thief named Helmstan was scratched in the face by a bramble while fleeing the scene of the crime. In court, the scratch was used as evidence against him.[61]

Oath

In compurgation or trial by oath, a defendant swore oaths to prove his innocence without cross-examination. A defendant was expected to bring oath-helpers (Latin: juratores), neighbours willing to swear to his good character or "oathworthiness". In the Christian society of Anglo-Saxon England, a false oath was a grave offence against God and could endanger one's immortal soul.[62][63]

In Anglo-Saxon law, "denial is always stronger than accusation".[64] The defendant was acquitted if he produced the necessary number of oaths.[62] If a defendant's community believed him to be guilty or generally untrustworthy, he would be unable to gather oath-helpers and would lose his case.[65] This system was vulnerable to abuse. A defendant might be unable to gather oath-helpers because his opponent was more powerful or influential within the community.[66]

The number of oaths needed depended on the seriousness of the accusation and the person's social status. If the law required oaths valued at 1200 shillings, then a thegn would not need any oath-helpers because his wergeld equalled 1200 shillings. However, a ceorl (200 shilling wergeld) would need oath-helpers.[64]

Ordeal

When a defendant failed to establish his innocence by oath in criminal cases (such as murder, arson, forgery, theft and witchcraft), he might still redeem himself through trial by ordeal. Trial by ordeal was an appeal to God to reveal perjury, and its divine nature meant it was regulated by the church. The ordeal had to be overseen by a priest at a place designated by the bishop. The most common forms in England were ordeal by hot iron and ordeal by water.[67] Before a defendant was put through the ordeal, the plaintiff had to establish a prima facie case under oath. The plaintiff was assisted by his own supporters or "suit", who might act as witnesses for the plaintiff.[63]

Final judgement

The final judgement was made collectively by the suitors of the court, especially the thegns. In the Danelaw, judgement might be made by a group of "doomsmen" or judges. There is also evidence that those presiding over the court sometimes issued their own judgements.[68]

A court could order the guilty party to pay a fine, compensate a victim, or forfeit property. A religious penalty, such as a penance, might also be imposed. In land disputes, a court could order the restoration of property to a successful litigant. Sometimes resolutions took the form of compromise. For example, a party who lost their claim to land might be given a life-tenure in the property.[69]

The most serious crimes (murder, treachery to one's lord, arson, house-breaking, and open theft) were punishable by death and forfeiture. Hanging by the gallows and beheading were common forms of execution. A woman convicted of murder by witchcraft was punished by drowning.[70] According to the laws of Æthelstan, thieves over 15 years of age who stole more than 12 pence were to be executed (men by stoning, women by burning, and free women could be pushed off a cliff or drowned).[71]

In Cnut's code, a first criminal offence usually merited compensation to victims and fines to the king. Later offences saw progressively severe forms of bodily mutilation. Cnut also introduced outlawry, a punishment only the king could remove.[16]

Anglo-Saxon law assumed that a man's wife and children were his accomplices in any crime. If a man could not return or pay for stolen property, he and his family could be enslaved.[72]

Kinship law

One of the foundations of Anglo-Saxon law was the extended family or kindred (Old English: mægþ). Membership in a kindred provided the individual with protection and security.[73]

In the case of homicide, the victim's family was responsible for avenging him or her through a blood feud. The law set criteria for legitimate blood feuds. A family did not have the right to retaliate if a member was killed while stealing property, committing capital crimes, or resisting capture. A person was exempt from retaliation if he killed while:[74]

- Fighting for his lord

- Protecting his family from attack

- Defending his wife, daughter, sister, or mother from attempted rape (the murder had to take place during the attack)

Kings and the church promoted financial compensation (Old English: bote) for death or injury as an alternative to blood feuds. In the case of death, the victim's family was owed the weregild ("man price"). A person's weregild was greater or lesser depending on social status.[75]

Cnut's code allowed secular clergy to demand or pay compensation in a feud. However, monks were prohibited because they had abandoned their "kin-law when [they bowed] to [monastic] rule-law".[76]

Social class

A man had to own at least five hides of land to be considered a thegn (nobleman). Ealdormen (and later earls) were the highest-ranking nobles. High-ranking churchmen such as archbishops, bishops, and abbots also formed part of the aristocracy.[77]

There were various categories of freemen:[78]

- Geneats performed riding service (carried messages, transported strangers to the village, cared for horses, and acted as the lord's bodyguard)

- Ceorls held one to two hides of land

- Geburs held a virgate of land

- Cotsetlan (cottage dwellers) held five acres

- Homeless labourers were paid in food and clothing

Thegns enjoyed greater rights and privileges than did ordinary freemen. The weregild of a ceorl was 200 shillings while that of a thegn was 1200. In court, a thegn's oath was equal to the oath of six ceorls.[79]

Slavery was widespread in early medieval England. The price of a slave (Old English: þēow) or thrall (Old Norse: þræll) was one pound or eight oxen. If a slave was killed, his murderer only had to pay the purchase price because slaves had no wergild. Because slaves had no property, they could not pay fines as a punishment for crime. Instead, slaves received corporal punishments such as flogging, mutilation, or death.[80]

Slavery was an inherited status. The slave population included the conquered Britons and their descendants. Some people were enslaved as war captives or as punishment for crimes (such as theft). Others became slaves due to unpaid debts. While owners had extensive power over their slaves, their power was not absolute. Slaves could be manumitted; however, only second- or third-generation descendants of freed slaves received all the privileges of a freeman.[81][82][44]

Slavery may have declined in the late eleventh century as it was considered a pious act for Christians to free their slaves on their deathbed. The church condemned the sale of slaves outside the country, and the internal trade declined in the twelfth century. It may have been more economic to settle slaves on land than to feed and house them, and the change to serfdom was probably an evolutionary change in status rather a clear distinction between the two.[83]

Land law

Types

Land in Anglo-Saxon England can be divided into three types: bookland, loanland, and folkland.[84]

When a royal charter (Old English: boc) transferred land ownership from the king to another person, the land was known as bookland (Old English: bocland). Owning bookland carried three important benefits. First, food rent and other services owed to the king (except for the trinoda necessitas) were transferred to the new owner.[85] Second, the charter itself served as important evidence of ownership in case of a dispute. Third, the charter granted perpetual ownership to the grantee and his heirs unless freely alienated. The king had special jurisdiction over legal disputes involving bookland, and sometimes the king had to consent to its alienation. Originally, only religious houses received bookland, but kings started granting it to laymen in the late 8th century.[86]

When a king, religious house, or lay lord leased property to others, it became loanland (Old English: lænland). Most of the surviving evidence involves leases from religious houses. Sometimes land was leased to pay back a monetary loan; as part of such an agreement, a lender paid a lump sum of money to the borrower in exchange for the right to collect the loanland's income for a set period (commonly three lives). For example, one document records loanland granted for three years in return for a loan of £3. Leases were witnessed in court, and written documents have survived, such as chirographs.[87]

The meaning of folkland (Old English: folcland) is unclear, and historians have proposed at least three definitions. The first view, popular in the 19th century, is that folkland was a form of communal property belonging to the nation (the folk). The second view is that it belonged to the Crown but was separate from the king's personal property; it could therefore be leased but not permanently alienated. The third view is that folkland referred to land held according to custom or tradition, which included all land except bookland.[88]

Lordship and dependents

Lords granted peasants land in return for rent and labour. It was also common for free peasants who owned their land to submit to a lord for protection through a process called commendation. Peasants who commended their land owed their lord labour service. Theoretically, a commended peasant could transfer his land to a new lord whenever he liked. In reality, this was not permitted. By 1066, manorialism was entrenched in England.[89]

Inheritance

Many parts of England (including Kent, East Anglia, and Dorset) practised forms of partible inheritance in which land was equally divided among heirs. In Kent, this took the form of gavelkind.[90]

Peace and protection

Every house had a peace (Old English: mund). Intruders and other violators of the peace had to pay a fine called a mundbyrd. A man's status determined the amount of the mundbyrd. The laws of Æthelberht set the mundbyrd for the king at 50 shillings, the eorl (noble) at 12s., and the ceorl (freeman) at 6s. In Alfred the Great's time, the king's mundbyrd was £5.[91]

Mund is the origin of the king's peace.[82] Initially, the king's mund was limited to the royal residence. As royal power and responsibilities grew, the king's peace was applied to other areas: shire courts, hundred courts, highways, rivers, bridges, churches, monasteries, markets, and towns. Theoretically, the king was present at these places. King's imposed fines called wites as punishments for breaches of the king's peace.[92]

Individuals received protection through kinship ties or by entering the service of a lord.[93] The king could grant individuals a personal peace (or grith). For example, the king's peace protected his counselors when travelling to and from meetings of the witan.[94] Foreign traders and others not protected by lordship or kinship ties were under the king's protection.[95]

Compensation

Anglo-Saxon law mandated that a person pay compensation when injuring another person. The injured body part determined the amount of compensation. According to Æthelberht's law, pulling someone's hair cost 50 sceattas, a severed foot cost 50 shillings, and "damaging the kindling limb" (the reproductive organs) cost 300 shillings.[96]

In the case of murder, the victim's kindred could forego a blood feud in return for payment of a wergild. In addition to paying the king a wite (fine), the killer also owed compensation to the victim's lord. Some crimes could not be satisfied by financial compensation. These botless crimes were punished with death or forfeiture of property. They included:[97]

- secret murder, such as by poison or witchcraft

- treachery to one's lord

- arson

- house-breaking

- open theft

Religion and the church

The creation of written law codes coincided with Christianisation, and the church received special privileges and protections in the earliest codes. The Law of Æthelberht demanded compensation for offences against church property:[98]

- 12-fold compensation for church property

- 11-fold for a bishop's property

- 9-fold for a priest's property

- 6-fold for a deacon's property

- 3-fold for a cleric's property

In the late 7th century, the laws of Kent and Wessex supported the church in various ways. Failure to receive baptism was punished with a financial penalty, and the oath of a communicant was worth more than a non-communicant in legal proceedings. Laws supported Sabbath observance and payment of church-scot (church dues). Laws also established rights to church sanctuary .[99]

See also

- History of English law

- Government in Norman and Angevin England

- Cyfraith Hywel (Wales)

- Early Irish law

- Leges inter Brettos et Scottos (Scotland)

Citations

- ↑ Baker 2019, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Potter 2015, p. 9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Baker 2019, p. 10.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Vinogradoff 1911, p. 37.

- ↑ Potter 2015, p. 10.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Baker 2019, p. 4.

- ↑ Ecclesiastical History of the English People II.5 quoted in Potter 2015, p. 12.

- ↑ Potter 2015, pp. 10–12.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Baker 2019, p. 5.

- ↑ Potter 2015, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 21.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 47.

- ↑ IV Æthelstan 1, printed in Liebermann 1903, pp. 146–183. Quoted in Hudson 2012, p. 25.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Lyon 1980, p. 4.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Potter 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ Baker 2019, p. 6.

- ↑ Vinogradoff 1911, p. 35–36.

- ↑ Baker 2019, p. 14, footnote 12.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 43.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Potter 2015, p. 23.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Loyn 1984, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hudson 2012, p. 50.

- ↑ Warren 1987, pp. 43 & 49.

- ↑ Potter 2015, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Hudson 2012, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Loyn 1984, p. 139.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Hudson 2012, p. 49.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 66.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Potter 2015, p. 24.

- ↑ Baker 2019, p. 11.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Hudson 2012, p. 54.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Loyn 1984, p. 143.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Potter 2015, p. 25.

- ↑ Potter 2015, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Hundred Ordinance 2, printed in Liebermann 1903, pp. 192–195. Quoted in Hudson 2012, p. 52.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Potter 2015, p. 26.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 68.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 45 & 54.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Lyon 1980, p. 91.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 Hudson 2012, p. 59.

- ↑ Baker 2019, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Baker 2019, p. 12.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 63.

- ↑ Jolliffe 1961, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 66.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 72.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 70.

- ↑ Swerian 4 printed in Liebermann 1903, pp. 396–399. Quoted in Hudson 2012, p. 71.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 71.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 99.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Swerian 5 printed in Liebermann 1903, pp. 396–399. Quoted in Hudson 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 78.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 80.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 81.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Potter 2015, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Baker 2019, p. 7.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Lyon 1980, p. 100.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 101.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 84.

- ↑ Potter 2015, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 92.

- ↑ Potter 2015, p. 19.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 94.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 83.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Potter 2015, pp. 10–14 & 36.

- ↑ Fletcher 2003, p. 118 quoted in Potter 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 89.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 90.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Green 2017, pp. 11 & 121.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Jolliffe 1961, p. 5.

- ↑ Green 2017, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 94.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 77.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 94 & 97.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Hudson 2012, p. 102.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, pp. 77–78 & 80.

- ↑ Jolliffe 1961, p. 4.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 41.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 42.

- ↑ Jolliffe 1961, p. 15.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, p. 43.

- ↑ Yorke 1990, p. 18.

- ↑ Potter 2015, p. 13.

- ↑ Lyon 1980, pp. 84 & 92.

- ↑ Loyn 1984, p. 44.

- ↑ Loyn 1984, p. 45.

References

- Baker, John (2019). An Introduction to English Legal History (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-254074-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=bPqNDwAAQBAJ.

- Fletcher, Richard (2003). Bloodfeud: Murder and Revenge in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford. ISBN 9780195179446. https://books.google.com/books?id=Mz7k0NeveBYC.

- Green, Judith A. (2017). Forging the Kingdom: Power in English Society, 973–1189. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521193597. https://books.google.com/books?id=xEzODgAAQBAJ.

- Hudson, John (2012). The Oxford History of the Laws of England: 871-1216. 2. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198260301.001.0001. ISBN 9780198260301. https://books.google.com/books?id=2hO-2QeHPZYC.

- Jolliffe, J. E. A. (1961). The Constitutional History of Medieval England from the English Settlement to 1485 (4th ed.). Adams and Charles Black. https://archive.org/details/constitutionalhi0000joll.

- Liebermann, Felix (1903) (in German). Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. 1. Halle: M. Niemeyer. https://archive.org/details/diegesetzederang01liebuoft.

- Loyn, H. R. (1984). The Governance of Anglo-Saxon England, 500–1087. Governance of England. 1. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804712170. https://archive.org/details/governanceofangl0000loyn.

- Lyon, Bryce (1980). A Constitutional and Legal History of Medieval England (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95132-4. 1st edition available to read online here.

- Potter, Harry (2015). Law, Liberty and the Constitution: A Brief History of the Common Law. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781783270118. https://books.google.com/books?id=9lDoCQAAQBAJ.

- Warren, W. L. (1987). "The Anglo-Saxon Legacy". The Governance of Norman and Angevin England, 1086–1272. The Governance of England. 2. Stanford, CA, US: Stanford University Press. pp. 25–55. ISBN 0-8047-1307-3. https://archive.org/details/governanceofnorm0000warr_y8g2.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. B. A. Seaby. ISBN 0-415-16639-X. https://archive.org/details/kingskingdomsofe0000york.

Further reading

Editions

- Felix Liebermann, Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen (Halle, 1903–1916), 3 vols. with translations, notes and commentary is indispensable.

- (in German) Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. 1. Halle: M. Niemeyer. 1903. https://archive.org/details/diegesetzederang01liebuoft. (edition and translation)

- (in German) Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. 2. Halle: M. Niemeyer. 1906. https://archive.org/details/diegesetzederang02liebuoft. (dictionary and glossary)

- (in German) Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. 3. Halle: M. Niemeyer. 1916. https://archive.org/details/diegesetzederang03liebuoft. (commentary)

- Lisi Oliver, The Beginnings of English Law (Toronto, 2002), text, translation, and commentary for the laws of Aethelbert, Hlohere, Eadric, and Wihtred.

- Reinhold Schmid, Gesetze der Angelsachsen (2nd ed., Leipzig, 1858), full glossary.

- Benjamin Thorpe, Ancient Laws and Institutes of England (1840), not very trustworthy.

- Domesday Book, i. ii. (Rec. Comm.);

- Codex Diplomaticus Aevi Saxonici, i.-vi. ed. J. M. Kemble (1839–1848);

- Cartularium Saxonicum (up to 940), ed. Walter de Gray Birch (1885–1893);

- John Earle, A Hand-book to the Land Charters, and other Saxonic Documents. (Oxford, 1888);

- Benjamin Thorpe, Diplomatarium Anglicum aevi Saxonici: a collection of English charters ... with a translation of the Anglo-Saxon (London, 1865)

- Facsimiles of Ancient Charters, edited by the Ordnance Survey and by the British Museum;

- Arthur West Haddan and William Stubbs, Councils of Great Britain, i.-iii. (Oxford, 1869–1878).

- Agnes J. Robertson, The Laws of the Kings of England from Edmund to Henry I (Cambridge, 1925)

Modern works

- Konrad Maurer, Über Angelsachsische Rechtsverhaltnisse, Kritische Ueberschau (Munich, 1853 ff.), account of the history of Anglo-Saxon law;

- Essays on Anglo-Saxon Law, by H. Adams, H. C. Lodge, J. L. Laughlin and E. Young (1876);

- J. M. Kemble, Saxons in England;

- F. Palgrave, History of the English Commonwealth;

- William Stubbs, Constitutional History of England, i.;

- Sir Frederick Pollock and Frederic William Maitland, History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I, (1895)

- H. Brunner, Zur Rechtsgeschichte der römisch-germanischen Urkunde (1880);

- Sir Frederick Pollock, The King's Peace (Oxford Lectures);

- Frederic Seebohm, The English Village Community;

- Frederic Seebohm, Tribal Custom in Anglo-Saxon Law;

- Heinrich Marquardsen, Haft und Burgschaft im Angelsachsischen Recht;

- Hermann Jastrow, Über die Strafrechtliche Stellung der Sklaven, Otto von Gierke's Untersuchungen, i.;

- J. C. H. R. Steenstrup, Normannerne, iv.;

- F. W. Maitland, Domesday and Beyond (Cambridge, 1897);

- H. M. Chadwick, Studies on Anglo-Saxon Institutions (1905);

- Charles E. Tucker, Jr., "Anglo-Saxon Law: Its Development and Impact on the English Legal System" (USAFA Journal of Legal Studies, 1991)

- P. Vinogradoff, "Folcland" in the English Historical Review, 1893;

- P. Vinogradoff, "Romanistische Einflusse im Angelsächsischen Recht: Das Buchland" in the Mélanges Fitting, 1907;

- P. Vinogradoff, "The Transfer of Land in Old English Law" in the Harvard Law Review, 1907.

- Patrick Wormald, The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, Vol I, (Blackwell, 1999)

- Jay Paul Gates and Nicole Marafioti, eds. 2014. Capital and Corporal Punishment in Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843839187.

- Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge, Alfred the Great: Asser's life of King Alfred and other Contemporary sources (Penguin Classics, 1983)

External links

- Medieval Sourcebook: The Anglo-Saxon Dooms, 560-975

- Medieval Sourcebook: Medieval legal history

- Laws of Alfred and Ine (georgetown.edu)

- Anglo-Saxon Law: Its Development and Impact on the English Legal System (Charles Tucker, USAFA Journal of Legal Studies)

- Early English Laws research project

|

KSF

KSF