Economic inequality

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 51 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 51 min

Economic inequality is an umbrella term for a) income inequality or distribution of income (how the total sum of money paid to people is distributed among them), b) wealth inequality or distribution of wealth (how the total sum of wealth owned by people is distributed among the owners), and c) consumption inequality (how the total sum of money spent by people is distributed among the spenders). Each of these can be measured between two or more nations, within a single nation, or between and within sub-populations (such as within a low-income group, within a high-income group and between them, within an age group and between inter-generational groups, within a gender group and between them etc, either from one or from multiple nations).[2]

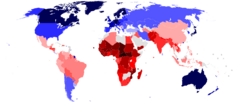

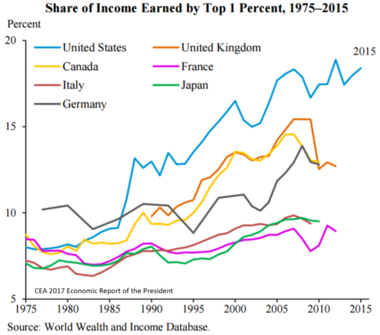

Income inequality metrics are used for measuring income inequality,[3] the Gini coefficient being a widely used one. Another type of measurement is the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index, which is a statistic composite index that takes inequality into account.[4] Important concepts of equality include equity, equality of outcome, and equality of opportunity. Whereas globalization has reduced the inequality between nations, it has increased the inequality within the population in most nations.[5][6][7][8] Income inequality between nations peaked in the 1970s, when world income was distributed bimodally into "rich" and "poor" countries. Since then, income levels across countries have been converging, with most people now living in middle-income countries.[5][9] However, inequality within the population in most has risen significantly in the last 30 years, particularly among advanced countries.[5][6][7][8] In this period, approximately 90 percent of advanced nations increased their income inequality with over 70% nations recording their Gini coefficient increase, exceeding two points.[5]

Research has generally linked economic inequality to political and social instability, including revolution, democratic breakdown and civil conflict.[5][10][11][12] Research suggests that greater inequality hinders economic growth and macroeconomic stability, and that land and human capital inequality reduce growth more than inequality of income.[5][13] Inequality is at the center stage of economic policy debate across the globe, as government tax and spending policies have significant effects on income distribution.[5] In advanced economies, taxes and transfers decrease income inequality by one-third, with most of this being achieved via public social spending (such as pensions and family benefits).[5] While the "optimum" amount of economic inequality is widely debated, there is a near-universal belief that complete economic equality (Gini of zero) would be undesirable and unachieveable.[14]: 1

Measurements

In 1820, the ratio between the income of the top and bottom 20 percent of the world's population was three to one. By 1991, it was eighty-six to one.[15] A 2011 study titled "Divided we Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising" by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) sought to explain the causes for this rising inequality by investigating economic inequality in OECD countries; it concluded that the following factors played a role:[16]

- Changes in the structure of households can play an important role. Single-headed households in OECD countries have risen from an average of 15% in the late 1980s to 20% in the mid-2000s, resulting in higher inequality.

- Assortative mating refers to the phenomenon of people marrying people with similar background, for example doctors marrying other doctors rather than nurses. OECD found out that 40% of couples where both partners work belonged to the same or neighbouring earnings deciles compared with 33% some 20 years before.[17]

- In the bottom percentiles, number of hours worked has decreased.[17]

- The main reason for increasing inequality seems to be the difference between the demand for and supply of skills.[17]

The study made the following conclusions about the level of economic inequality:

- Income inequality in OECD countries is at its highest level for the past half century. The ratio between the bottom 10% and the top 10% has increased from 1:7 to 1:9 in 25 years.[17]

- There are tentative signs of a possible convergence of inequality levels towards a common and higher average level across OECD countries.[17]

- With very few exceptions (France , Japan , and Spain ), the wages of the 10% best-paid workers have risen relative to those of the 10% lowest paid.[17]

A 2011 OECD study investigated economic inequality in Argentina , Brazil , China , India, Indonesia, Russia , and South Africa . It concluded that key sources of inequality in these countries include "a large, persistent informal sector, widespread regional divides (e.g., urban-rural), gaps in access to education, and barriers to employment and career progression for women."[17]

A study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research at United Nations University reported that the richest 1% of adults alone owned 40% of global assets in the year 2000. The three richest people in the world possess more financial assets than the lowest 48 nations combined.[18] The combined wealth of the "10 million dollar millionaires" grew to nearly $41 trillion in 2008.[19]

Oxfam's 2021 report on global inequality said that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased economic inequality substantially; the wealthiest people across the globe were impacted the least by the pandemic and their fortunes recovered quickest, with billionaires seeing their wealth increase by $3.9 trillion, while at the same time the number of people living on less than $5.50 a day likely increased by 500 million.[20] According to economist Joseph Stiglitz, the pandemic's "most significant outcome" will be rising economic inequality in the United States and between the developed and developing world.[21] The 2024 Oxfam report found a significant increase in inequality as roughly five billion people have become poorer while at the same time the fortunes of the five richest individuals have doubled. The report warns that current trends are paving the way for the world's first trillionaire within a decade and global poverty eradication being postponed for 229 years.[22]

According to PolitiFact, the top 400 richest Americans "have more wealth than half of all Americans combined."[24][25][26][27] According to The New York Times on July 22, 2014, the "richest 1 percent in the United States now own more wealth than the bottom 90 percent".[28] Inherited wealth may help explain why many Americans who have become rich may have had a "substantial head start".[29][30] A 2017 report by the IPS said that three individuals, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, own as much wealth as the bottom half of the population, or 160 million people, and that the growing disparity between the wealthy and the poor has created a "moral crisis", noting that "we have not witnessed such extreme levels of concentrated wealth and power since the first gilded age a century ago."[31][32] In 2016, the world's billionaires increased their combined global wealth to a record $6 trillion.[33] In 2017, they increased their collective wealth to 8.9 trillion.[34] In 2018, U.S. income inequality reached the highest level ever recorded by the Census Bureau.[35]

The existing data and estimates suggest a large increase in international (and more generally inter-macroregional) components between 1820 and 1960. It might have slightly decreased since that time at the expense of increasing inequality within countries.[36] The United Nations Development Programme in 2014 asserted that greater investments in social security, jobs, and laws that protect vulnerable populations are necessary to prevent widening income inequality.[37]

There is a significant difference in the measured wealth distribution and the public's understanding of wealth distribution. Michael Norton of the Harvard Business School and Dan Ariely of the Department of Psychology at Duke University found this to be true in their research conducted in 2011. The actual wealth going to the top quintile in 2011 was around 84%, whereas the average amount of wealth that the general public estimated to go to the top quintile was around 58%.[38]

According to a 2020 study, global earnings inequality has decreased substantially since 1970. During the 2000s and 2010s, the share of earnings by the world's poorest half doubled.[39] Two researchers claim that global income inequality is decreasing due to strong economic growth in developing countries.[40] According to a January 2020 report by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, economic inequality between states had declined, but intrastate inequality has increased for 70% of the world population over the period 1990–2015.[41] In 2015, the OECD reported in 2015 that income inequality is higher than it has ever been within OECD member nations and is at increased levels in many emerging economies.[42] According to a June 2015 report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

Widening income inequality is the defining challenge of our time. In advanced economies, the gap between the rich and poor is at its highest level in decades. Inequality trends have been more mixed in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs), with some countries experiencing declining inequality, but pervasive inequities in access to education, health care, and finance remain.[43]

In October 2017, the IMF warned that inequality within nations, in spite of global inequality falling in recent decades, has risen so sharply that it threatens economic growth and could result in further political polarization. The Fund's Fiscal Monitor report said that "progressive taxation and transfers are key components of efficient fiscal redistribution."[44] In October 2018 Oxfam published a Reducing Inequality Index which measured social spending, tax and workers' rights to show which countries were best at closing the gap between the rich and the poor.[45]

The 2022 World Inequality Report, a four-year research project organized by the economists Lucas Chancel, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, shows that "the world is marked by a very high level of income inequality and an extreme level of wealth inequality" and that these inequalities "seem to be about as great today as they were at the peak of western imperialism in the early 20th century." According to the report, the bottom half of the population owns 2% of global wealth, while the top 10% owns 76% of it. The top 1% owns 38%.[46][47][48]

Wealth distribution within individual countries

The wealth is calculated by various factors, for instance: liabilities, debts, exchange rates and their expected development, real estate prices, human resources, natural resources and technical advancements, etc.

Income distribution within individual countries

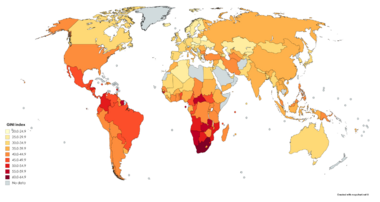

Income inequality is measured by Gini coefficient (expressed in percent %) that is a number between 0 and 1. Here 0 expresses perfect equality, meaning that everyone has the same income, whereas 1 represents perfect inequality, meaning that one person has all the income and others have none. A Gini index value above 50% is considered high; countries including Brazil, Colombia, South Africa, Botswana, and Honduras can be found in this category. A Gini index value of 30% or above is considered medium; countries including Vietnam, Mexico, Poland, the United States, Argentina, Russia and Uruguay can be found in this category. A Gini index value lower than 30% is considered low; countries including Austria, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Slovenia, Sweden, and Ukraine can be found in this category.[49] In the low-income inequality category (below 30%) is a wide representation of countries previously being part of Soviet Union or its satellites, like Slovakia, Czech Republic, Ukraine and Hungary.

In 2012 the Gini index for income inequality for whole European Union was only 30.6%.

Income distribution can differ from wealth distribution within each country. The wealth inequality is also measured in Gini index. There the higher Gini index signify greater inequality within the wealth distribution in country, 0 means total wealth equality and 1 represents situation, where everyone has no wealth, except an individual that has everything. For instance, countries like Denmark, Norway and Netherlands, all belonging to the last category (below 30%, low-income inequality) also have very high Gini index in wealth distribution, ranging from 70% up to 90%.

Consumption distribution within individual countries

In economics, the consumption distribution or consumption inequality is an alternative to the income distribution or wealth distribution for judging economic inequality, comparing levels of consumption rather than income or wealth.[50] This is an important measure of inequality as the basic utility of the wealth or income is the expenditure.[51] People experience the inequality directly in consumption, rather than income or wealth.[52]

Factors proposed to affect economic inequality

There are various reasons for economic inequality within societies, including both global market functions (such as trade, development, and regulation) as well as social factors (including gender, race, and education).[53] Recent growth in overall income inequality, at least within the OECD countries, has been driven mostly by increasing inequality in wages and salaries.[16]

Economist Thomas Piketty argues that widening economic disparity is an inevitable phenomenon of free market capitalism when the rate of return of capital (r) is greater than the rate of growth of the economy (g).[54] According to an IMF report in 2016, after reviewing four decades of neoliberalism, it had warned that certain neoliberal policies including privatization, public spending cuts, and deregulation, have resulted in "increased inequality" and are stunting economic growth globally.[55][56]

Labour market

In modern market economies, if competition is imperfect; information unevenly distributed; opportunities to acquire education and skills unequal; market failure results. Many such imperfect conditions exist in virtually every market. According to Joseph Stiglitz this means that there is an enormous potential role for government to correct such market failures.[57]

In the United States, real wages are flat over the past 40 years for occupations across income and education levels, e.g., auto mechanics, cashiers, doctors, and software engineers.[58] However, stock ownership favors higher income and education levels,[59] thereby resulting in disparate investment income.

Taxes

Another cause is the rate at which income is taxed coupled with the progressivity of the tax system. A progressive tax is a tax by which the tax rate increases as the taxable base amount increases.[60][61] In a progressive tax system, the level of the top tax rate will often have a direct impact on the level of inequality within a society, either increasing it or decreasing it, provided that income does not change as a result of the change in tax regime. Additionally, steeper tax progressivity applied to social spending can result in a more equal distribution of income across the board.[62] Tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit in the US can also decrease income inequality.[63] The difference between the Gini index for an income distribution before taxation and the Gini index after taxation is an indicator for the effects of such taxation.[64]

Education

An important factor in the creation of inequality is variation in individuals' access to education.[66] Education, especially in an area where there is a high demand for workers, creates high wages for those with this education.[67] However, increases in education first increase and then decrease growth as well as income inequality. As a result, those who are unable to afford an education, or choose not to pursue optional education, generally receive much lower wages. The justification for this is that a lack of education leads directly to lower incomes, and thus lower aggregate saving and investment. Conversely, quality education raises incomes and promotes growth because it helps to unleash the productive potential of the poor.[68]

Access to education was in turn influenced by land inequalities. In the less industrialized parts of 19th century Europe, for example, landowners still held more political power than industrialists. These landowners did not benefit from educating their workers as much as industrialists did, since "educated workers have more incentives to migrate to urban, industrial areas than their less educated counterparts."[69] Consequently, lower incentives to promote education in regions where land inequality was high led to lower levels of numeracy in these regions.[69]

Economic liberalism, deregulation and decline of unions

John Schmitt and Ben Zipperer (2006) of the CEPR point to economic liberalism and the reduction of business regulation along with the decline of union membership as one of the causes of economic inequality. In an analysis of the effects of intensive Anglo-American liberal policies in comparison to continental European liberalism, where unions have remained strong, they concluded "The U.S. economic and social model is associated with substantial levels of social exclusion, including high levels of income inequality, high relative and absolute poverty rates, poor and unequal educational outcomes, poor health outcomes, and high rates of crime and incarceration. At the same time, the available evidence provides little support for the view that U.S.-style labor market flexibility dramatically improves labor-market outcomes. Despite popular prejudices to the contrary, the U.S. economy consistently affords a lower level of economic mobility than all the continental European countries for which data is available."[70]

More recently, the International Monetary Fund has published studies which found that the decline of unionization in many advanced economies and the establishment of neoliberal economics have fueled rising income inequality.[71][72]

Contrary to the proponents of neoliberalism, trickle-down economics have been proven to not be effective in resolving economic inequalities but have instead worsened it.[73]

Technology

The growth in importance of information technology has been credited with increasing income inequality.[74] Technology has been called "the main driver of the recent increases in inequality" by Erik Brynjolfsson, of MIT.[75] In arguing against this explanation, Jonathan Rothwell notes that if technological advancement is measured by high rates of invention, there is a negative correlation between it and inequality. Countries with high invention rates — "as measured by patent applications filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty" — exhibit lower inequality than those with less. In one country, the United States, "salaries of engineers and software developers rarely reach" above $390,000/year (the lower limit for the top 1% earners).[76]

Some researchers, such as Juliet B. Schor, highlight the role of for-profit online sharing economy platforms as an accelerator of income inequality and calls into question their supposed contribution in empowering outsiders of the labour market.[77]

Taking the example of TaskRabbit, a labour service platform, she shows that a large proportion of providers already have a stable full-time job and participate part-time in the platform as an opportunity to increase their income by diversifying their activities outside employment, which tends to restrict the volume of work remaining for the minority of platform workers.

In addition, there is an important phenomenon of labour substitution as manual tasks traditionally performed by workers without a degree (or just a college degree) integrated into the labour market in the traditional economy sectors are now performed by workers with a high level of education (in 2013, 70% of TaskRabbit's workforce held a bachelor's degree, 20% a master's degree and 5% a PhD).[78] The development of platforms, which are increasingly capturing demand for these manual services at the expense of non-platform companies, may therefore benefit mainly skilled workers who are offered more earning opportunities that can be used as supplemental or transitional work during periods of unemployment.

It has also been proposed that information technologies contribute to "winner take most" market concentration, reducing the need for labor across competing suppliers.[79] Market concentration drives down labor's share of the GDP, increasing the wealth of capital and thereby exacerbating inequality.

Automation

Economists have linked automation to increases in economic inequality, as automation raises the returns to wealth and contributes to stagnating wages at the lower end of the wage distribution.[80] Several economists have suggested that automation has increased income inequality by causing low skill jobs to be replaced with machines operated by technologically skilled workers, thereby reducing the demand for unskilled labor while increasing the demand for skilled labor.[14]: 1

Globalization

Trade liberalization may shift economic inequality from a global to a domestic scale.[82] When rich countries trade with poor countries, the low-skilled workers in the rich countries may see reduced wages as a result of the competition, while low-skilled workers in the poor countries may see increased wages. Trade economist Paul Krugman estimates that trade liberalisation has had a measurable effect on the rising inequality in the United States. He attributes this trend to increased trade with poor countries and the fragmentation of the means of production, resulting in low skilled jobs becoming more tradeable.[83]

Anthropologist Jason Hickel contends that globalization and "structural adjustment" set off the "race to the bottom", a significant driver of surging global inequality. Another driver Hickel mentions is the debt system which advanced the need for structural adjustment in the first place.[84]

Gender

In many countries, there is a gender pay gap in favor of males in the labor market. Several factors other than discrimination contribute to this gap. On average, women are more likely than men to consider factors other than pay when looking for work and may be less willing to travel or relocate.[86][87] Thomas Sowell, in his book Knowledge and Decisions, claims that this difference is due to women not taking jobs due to marriage or pregnancy. A U.S. Census's report stated that in US once other factors are accounted for there is still a difference in earnings between women and men.[88] A study done on three post-soviet countries Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan reveals that gender is one of the driving forces of income inequality, and being female has a significant negative effect on income when other factors are held equal. The results show more than 50% gender pay gap in all three countries.[89] These findings are because usually employers tend to avoid hiring women because of possible maternity leave. Other reason for this can be occupational segregation, which implies that women are usually accumulated in lower-paid positions and sectors, such as social services and education.

Race

As a general rule, races which have been historically and systematically colonized (typically indigenous ethnicities) continue to experience lower levels of financial stability in the present day. The global South is considered to be particularly victimized by this phenomenon, though the exact socioeconomic manifestations change across different regions.[90]

Westernized Nations

While the progression of civil rights movements and justice reform has improved access to education and other economic opportunities in politically advanced nations, racial income and wealth disparity still exists.[91] In the United States for example, a survey[when?] of African American populations show that they are more likely to drop out of high school and college, are typically employed for fewer hours at lower wages, have lower than average intergenerational wealth, and are more likely to use welfare as young adults than their white counterparts.[92]

Mexican-Americans, while suffering less debilitating socioeconomic factors than black Americans, experience deficiencies in the same areas when compared to whites and have not assimilated financially to the level of stability experienced by white Americans as a whole.[93] These experiences are the effects of the measured disparity due to race in countries like the US, where studies show that in comparison to whites, blacks suffer from drastically lower levels of upward mobility, higher levels of downward mobility, and poverty that is more easily transmitted to offspring as a result of the disadvantage stemming from the era of slavery and post-slavery racism that has been passed through racial generations to the present.[94][95][96] These are lasting financial inequalities that apply in varying magnitudes to most non-white populations in nations such as the US, the UK, France, Spain, Australia, etc.[90]

Latin America

In the countries of the Caribbean, Central America, and South America, many ethnicities continue to deal with the effects of European colonization, and in general nonwhites tend to be noticeably poorer than whites in this region. In many countries with significant populations of indigenous races and those of Afro-descent (such as Mexico, Colombia, Chile, etc.) income levels can be roughly half as high as those experiences by white demographics, and this inequity is accompanied by systematically unequal access to education, career opportunities, and poverty relief. This region of the world, apart from urbanizing areas like Brazil and Costa Rica, continues to be understudied and often the racial disparity is denied by Latin Americans who consider themselves to be living in post-racial and post-colonial societies far removed from intense social and economic stratification despite the evidence to the contrary.[97]

Africa

African countries, too, continue to deal with the effects of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, which set back economic development as a whole for blacks of African citizenship more than any other region. The degree to which colonizers stratified their holdings on the continent on the basis of race has had a direct correlation in the magnitude of disparity experienced by nonwhites in the nations that eventually rose from their colonial status. Former French colonies, for example, see much higher rates of income inequality between whites and nonwhites as a result of the rigid hierarchy imposed by the French who lived in Africa at the time.[98] Another example is found in South Africa, which, still reeling from the socioeconomic impacts of Apartheid, experiences some of the highest racial income and wealth inequality in all of Africa.[94] In these and other countries like Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Sierra Leone, movements of civil reform have initially led to improved access to financial advancement opportunities, but data[when?] shows that for nonwhites this progress is either stalling or erasing itself in the newest generation of blacks that seek education and improved transgenerational wealth. The economic status of one's parents continues to define and predict the financial futures of African and minority ethnic groups.[99][needs update]

Asia

Asian regions and countries such as China, the Middle East, and Central Asia have been vastly understudied in terms of racial disparity, but even here the effects of Western colonization provide similar results to those found in other parts of the globe.[90] Additionally, cultural and historical practices such as the caste system in India leave their marks as well. While the disparity is greatly improving in the case of India, there still exists social stratification between peoples of lighter and darker skin tones that cumulatively result in income and wealth inequality, manifesting in many of the same poverty traps seen elsewhere.[100]

Economic development

Economist Simon Kuznets argued that levels of economic inequality are in large part the result of stages of development. According to Kuznets, countries with low levels of development have relatively equal distributions of wealth. As a country develops, it acquires more capital, which leads to the owners of this capital having more wealth and income and introducing inequality. Eventually, through various possible redistribution mechanisms such as social welfare programs, more developed countries move back to lower levels of inequality.[101]

Wealth concentration

Wealth concentration is the process by which, under certain conditions, newly created wealth concentrates in the possession of already-wealthy individuals or entities. Accordingly, those who already hold wealth have the means to invest in new sources of creating wealth or to otherwise leverage the accumulation of wealth, and thus they are the beneficiaries of the new wealth. Over time, wealth concentration can significantly contribute to the persistence of inequality within society. Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century argues that the fundamental force for divergence is the usually greater return of capital (r) than economic growth (g), and that larger fortunes generate higher returns.[102]

Rent seeking

Economist Joseph Stiglitz argues that rather than explaining concentrations of wealth and income, market forces should serve as a brake on such concentration, which may better be explained by the non-market force known as "rent-seeking". While the market will bid up compensation for rare and desired skills to reward wealth creation, greater productivity, etc., it will also prevent successful entrepreneurs from earning excess profits by fostering competition to cut prices, profits and large compensation.[103] A better explainer of growing inequality, according to Stiglitz, is the use of political power generated by wealth by certain groups to shape government policies financially beneficial to them. This process, known to economists as rent-seeking, brings income not from creation of wealth but from "grabbing a larger share of the wealth that would otherwise have been produced without their effort".[104]

Finance industry

Jamie Galbraith argues that countries with larger financial sectors have greater inequality, and the link is not an accident.[105][106][why?]

Global warming and climate change

2 per person than poorer (developing) countries.[107] Emissions are roughly proportional to GDP per person, though the rate of increase diminishes with average GDP/pp of about $10,000.

A 2019 study published in PNAS found that global warming plays a role in increasing economic inequality between countries, boosting economic growth in developed countries while hampering such growth in developing nations of the Global South. The study says that 25% of gap between the developed world and the developing world can be attributed to global warming.[109]

A 2020 report by Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute says that the wealthiest 10% of the global population were responsible for more than half of global carbon dioxide emissions from 1990 to 2015, which increased by 60%.[110] According to a 2020 report by the UNEP, overconsumption by the rich is a significant driver of the climate crisis, and the wealthiest 1% of the world's population are responsible for more than double the greenhouse gas emissions of the poorest 50% combined. Inger Andersen, in the foreword to the report, said "this elite will need to reduce their footprint by a factor of 30 to stay in line with the Paris Agreement targets."[111] A 2022 report by Oxfam found that the business investments of the wealthiest 125 billionaires emit 393 million metric tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions annually.[112]

In July 2023, a letter sent to the United Nations secretary general António Guterres and World Bank president Ajay Banga by a group of over 200 economists from 67 countries, including Jayati Ghosh, Joseph Stiglitz and Thomas Piketty, warned that if the sharp increase in economic inequality is not reversed, it will "entrench poverty and increase the risk of climate breakdown."[113]

Politics

Joseph Stiglitz argues in The Price of Inequality (2012) that the economic inequality is inevitable and permanent, because it is caused by the great amount of political power the richest have.[57] He wrote, "While there may be underlying economic forces at play, politics have shaped the market, and shaped it in ways that advantage the top at the expense of the rest."

Cognitive biases

Research has shown that biased decision-making does not alone explain a significant proportion of inequality, therefore inequality cannot be explained by cognitive biases of a specific sub-population, such as temporal discounting (i.e., not preferring immediate funds over larger future gains), overestimation (i.e. thinking you are better than you are at making decisions), over-placement (i.e. thinking you are better than the average person at making decisions), and extremeness aversion (i.e. taking the 'middle option' simply because it seems safer than the highest or lowest).[114]

Mitigating factors

Countries with a left-leaning legislature generally have lower levels of inequality.[116][117] Many factors constrain economic inequality – they may be divided into two classes: market driven, and government sponsored. The relative merits and effectiveness of each approach is a subject of debate:

Market forces outside of government intervention that can reduce economic inequality include:

- propensity to spend: with rising wealth & income, a person may spend more. In an extreme example, if one person owned everything, they would immediately need to hire people to maintain their properties, thus reducing the wealth concentration.[118] On the other hand, high-income persons have higher propensity to save.[119] Robin Maialeh then shows that increasing economic wealth decreases propensity to spend and increases propensity to invest which consequently leads to even greater growth rate of already rich agents.[120]

Typical government initiatives intended to reduce economic inequality include:

- Public education: increasing the supply of skilled labor and reducing income inequality due to education differentials.[121]

- Progressive taxation: the rich are taxed proportionally more than the poor, reducing the amount of income inequality in society if the change in taxation does not cause changes in income.[122]

Research shows that since 1300, the only periods with significant declines in wealth inequality in Europe were the Black Death and the two World Wars.[123] Historian Walter Scheidel posits that, since the Stone Age, only extreme violence, catastrophes and upheaval in the form of total war, Communist revolutions, the French Revolution , pestilence and state collapse have significantly reduced inequality.[124][125] He has stated that "only all-out thermonuclear war might fundamentally reset the existing distribution of resources" and that "peaceful policy reform may well prove unequal to the growing challenges ahead."[126][127] However, Scheidel also stated that "There is certainly room for incremental change, that's what the example of Latin America shows in the past 15 years or so."[125]

Policy responses intended to mitigate

A 2011 OECD study makes a number of suggestions to its member countries, including:[17]

- Well-targeted income-support policies.

- Facilitation and encouragement of access to employment.

- Better job-related training and education for the low-skilled (on-the-job training) would help to boost their productivity potential and future earnings.

- Better access to formal education.

Progressive taxation reduces absolute income inequality when the higher rates on higher-income individuals are paid and not evaded, and transfer payments and social safety nets result in progressive government spending.[128][129][130] Wage ratio legislation has also been proposed as a means of reducing income inequality. The OECD asserts that public spending is vital in reducing the ever-expanding wealth gap.[131]

Deferred investment programs that increase stock ownership amongst lower income levels can supplement income to compensate wage stagnation.[58]

The economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty recommend much higher top marginal tax rates on the wealthy, up to 50 percent, 70 percent or even 90 percent.[132] Ralph Nader, Jeffrey Sachs, the United Front Against Austerity, among others, call for a financial transaction tax (also known as the Robin Hood tax) to bolster the social safety net and the public sector.[133][134]

The Economist wrote in December 2013: "A minimum wage, providing it is not set too high, could thus boost pay with no ill effects on jobs....America's federal minimum wage, at 38% of median income, is one of the rich world's lowest. Some studies find no harm to employment from federal or state minimum wages, others see a small one, but none finds any serious damage."[135]

General limitations on and taxation of rent-seeking are popular across the political spectrum.[136]

Public policy responses addressing causes and effects of income inequality in the US include: progressive tax incidence adjustments, strengthening social safety net provisions such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children, welfare, the food stamp program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, organizing community interest groups, increasing and reforming higher education subsidies, increasing infrastructure spending, and placing limits on and taxing rent-seeking.[137]

A 2017 study in the Journal of Political Economy by Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson and Thierry Verdier argues that American "cutthroat" capitalism and inequality gives rise to technology and innovation that more "cuddly" forms of capitalism cannot.[138] As a result, "the diversity of institutions we observe among relatively advanced countries, ranging from greater inequality and risk-taking in the United States to the more egalitarian societies supported by a strong safety net in Scandinavia, rather than reflecting differences in fundamentals between the citizens of these societies, may emerge as a mutually self-reinforcing world equilibrium. If so, in this equilibrium, 'we cannot all be like the Scandinavians,' because Scandinavian capitalism depends in part on the knowledge spillovers created by the more cutthroat American capitalism."[138] A 2012 working paper by the same authors, making similar arguments, was challenged by Lane Kenworthy, who posited that, among other things, the Nordic countries are consistently ranked as some of the world's most innovative countries by the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Index, with Sweden ranking as the most innovative nation, followed by Finland, for 2012–2013; the U.S. ranked sixth.[139]

There are however global initiative like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 10 which aims to garner international efforts in reducing economic inequality considerably by 2030.[140]

Effects

A lot of research has been done about the effects of economic inequality on different aspects in society:

- Health: For long time the higher material living standards lead to longer life, as those people were able to get enough food, water and access to warmth. British researchers Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have found higher rates of health and social problems (obesity, mental illness, homicides, teenage births, incarceration, child conflict, drug use) in countries and states with higher inequality.[141][142] Their research included 24 developed countries, including most U.S. states, and found that in the more developed countries, such as Finland and Japan, the heath issues are much lower than in states with rather higher inequality rates, such as Utah and New Hampshire. Some studies link a surge in "deaths of despair", suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol related deaths, to widening income inequality.[143][144] Conversely, other research did not find these effects or concluded that research suffered from issues of confounding variables.[145]

- Social goods: British researchers Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have found lower rates of social goods (life expectancy by country, educational performance, trust among strangers, women's status, social mobility, even numbers of patents issued) in countries and states with higher inequality.[141][142]

- Social cohesion: Research has shown an inverse link between income inequality and social cohesion. In more equal societies, people are much more likely to trust each other, measures of social capital (the benefits of goodwill, fellowship, mutual sympathy and social connectedness among groups who make up a social units) suggest greater community involvement.

- Happiness: According to the 2019 World Happiness Report, increasing socioeconomic inequality, along with rising healthcare costs, surging addiction rates, and an unhealthy work–life balance, are causes of unhappiness around the world.[146][147]

- Crime: The cross national research shows that in societies with less economic inequality the homicide rates are consistently lower.[148] A 2016 study finds that interregional inequality increases terrorism.[149] Other research has argued inequality has little effect on crime rates.[150][151]

- Welfare: Studies have found evidence that in societies where inequality is lower, population-wide satisfaction and happiness tend to be higher.[152]({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})[153][154]

- Poverty: Study made by Jared Bernstein and Elise Gould suggest, that the poverty in the United States could have been reduced by the lowering of economic inequality for the past few decades.[155][156]

- Debt: Income inequality has been the driving factor in the growing household debt,[157][158] as high earners bid up the price of real estate and middle income earners go deeper into debt trying to maintain what once was a middle class lifestyle.[159]

- Economic growth: A 2016 meta-analysis found that "the effect of inequality on growth is negative and more pronounced in less developed countries than in rich countries", though the average impact on growth was not significant. The study also found that wealth inequality is more pernicious to growth than income inequality.[13]

- Civic participation: Higher income inequality led to less of all forms of social, cultural, and civic participation among the less wealthy.[160]

- Political instability: Studies indicate that economic inequality leads to greater political instability, including an increased risk of democratic breakdown[11][161][162][163][164] and civil conflict.[165][12] A significant impact of inequality on civil war probability has been found through anthropometric methods.[166]

- Political party responses: One study finds that economic inequality prompts attempts by left-leaning politicians to pursue redistributive policies while right-leaning politicians seek to repress the redistributive policies.[167]

Perspectives

Fairness vs. equality

According to Christina Starmans et al. (Nature Hum. Beh., 2017), the research literature contains no evidence on people having an aversion to inequality. In all studies analyzed, the subjects preferred fair distributions (inequity aversion) to equal distributions, in both laboratory and real-world situations. In public, researchers may loosely speak of equality instead of fairness, when referring to studies where fairness happens to coincide with equality, but in many studies fairness is carefully separated from equality and the results are univocal. Very young children seem to prefer fairness over equality.[168]

When people were asked, what would be the wealth of each quintile in their ideal society, they gave a 50-fold sum to the richest quintile than to the poorest quintile. The preference for inequality increases in adolescence, and so do the capabilities to favor fortune, effort and ability in the distribution.[168]

Preference for unequal distribution has been developed to the human race possibly because it allows for better co-operation and allows a person to work with a more productive person so that both parties benefit from the co-operation. Inequality is also said to be able to solve the problems of free-riders, cheaters and ill-behaving people, although this is heavily debated.[168] Researches demonstrate that people usually underestimate the level of actual inequality, which is also much higher than their desired level of inequality.[169]

In many societies, such as the USSR, the distribution led to protests from wealthier landowners.[170] In the current U.S., many feel that the distribution is unfair in being too unequal. In both cases, the cause is unfairness, not inequality, the researchers conclude.[168]

Socialist perspectives

Socialists attribute the vast disparities in wealth to the private ownership of the means of production by a class of owners, creating a situation where a small portion of the population lives off unearned property income by virtue of ownership titles in capital equipment, financial assets and corporate stock. By contrast, the vast majority of the population is dependent on income in the form of a wage or salary. In order to rectify this situation, socialists argue that the means of production should be socially owned so that income differentials would be reflective of individual contributions to the social product.[171]

Marxian economics attributes rising inequality to job automation and capital deepening within capitalism. The process of job automation conflicts with the capitalist property form and its attendant system of wage labor. In this analysis, capitalist firms increasingly substitute capital equipment for labor inputs (workers) under competitive pressure to reduce costs and maximize profits. Over the long term, this trend increases the organic composition of capital, meaning that less workers are required in proportion to capital inputs, increasing unemployment (the "reserve army of labour"). This process exerts a downward pressure on wages. The substitution of capital equipment for labor (mechanization and automation) raises the productivity of each worker, resulting in a situation of relatively stagnant wages for the working class amidst rising levels of property income for the capitalist class.[172]

Marxist socialists ultimately predict the emergence of a communist society based on the common ownership of the means of production, where each individual citizen would have free access to the articles of consumption (From each according to his ability, to each according to his need). According to Marxist philosophy, equality in the sense of free access is essential for freeing individuals from dependent relationships, thereby allowing them to transcend alienation.[173]

Meritocracy

Meritocracy favors an eventual society where an individual's success is a direct function of his merit, or contribution. Economic inequality would be a natural consequence of the wide range in individual skill, talent and effort in human population. David Landes stated that the progression of Western economic development that led to the Industrial Revolution was facilitated by men advancing through their own merit rather than because of family or political connections.[174]

Liberal perspectives

Most modern social liberals, including centrist or left-of-center political groups, believe that the capitalist economic system should be fundamentally preserved, but the status quo regarding the income gap must be reformed. Social liberals favor a capitalist system with active Keynesian macroeconomic policies and progressive taxation (to even out differences in income inequality). Research indicates that people who hold liberal beliefs tend to see greater income inequality as morally wrong.[175]

However, contemporary classical liberals and libertarians generally do not take a stance on wealth inequality, but believe in equality under the law regardless of whether it leads to unequal wealth distribution. In 1966 Ludwig von Mises, a prominent figure in the Austrian School of economic thought, explains:

The liberal champions of equality under the law were fully aware of the fact that men are born unequal and that it is precisely their inequality that generates social cooperation and civilization. Equality under the law was in their opinion not designed to correct the inexorable facts of the universe and to make natural inequality disappear. It was, on the contrary, the device to secure for the whole of mankind the maximum of benefits it can derive from it. Henceforth no man-made institutions should prevent a man from attaining that station in which he can best serve his fellow citizens.

Robert Nozick argued that government redistributes wealth by force (usually in the form of taxation), and that the ideal moral society would be one where all individuals are free from force. However, Nozick recognized that some modern economic inequalities were the result of forceful taking of property, and a certain amount of redistribution would be justified to compensate for this force but not because of the inequalities themselves.[176] John Rawls argued in A Theory of Justice[177] that inequalities in the distribution of wealth are only justified when they improve society as a whole, including the poorest members. Rawls does not discuss the full implications of his theory of justice. Some see Rawls's argument as a justification for capitalism since even the poorest members of society theoretically benefit from increased innovations under capitalism; others believe only a strong welfare state can satisfy Rawls's theory of justice.[178]

Classical liberal Milton Friedman believed that if government action is taken in pursuit of economic equality then political freedom would suffer. In a famous quote, he said:

A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.

Economist Tyler Cowen has argued that though income inequality has increased within nations, globally it has fallen over the 20 years leading up to 2014. He argues that though income inequality may make individual nations worse off, overall, the world has improved as global inequality has been reduced.[179]

Social justice arguments

Patrick Diamond and Anthony Giddens (professors of Economics and Sociology, respectively) hold that 'pure meritocracy is incoherent because, without redistribution, one generation's successful individuals would become the next generation's embedded caste, hoarding the wealth they had accumulated'.[180]

They also state that social justice requires redistribution of high incomes and large concentrations of wealth in a way that spreads it more widely, in order to "recognize the contribution made by all sections of the community to building the nation's wealth." (Patrick Diamond and Anthony Giddens, June 27, 2005, New Statesman)[181]

Pope Francis stated in his Evangelii gaudium, that "as long as the problems of the poor are not radically resolved by rejecting the absolute autonomy of markets and financial speculation and by attacking the structural causes of inequality, no solution will be found for the world's problems or, for that matter, to any problems."[182] He later declared that "inequality is the root of social evil."[183]

When income inequality is low, aggregate demand will be relatively high, because more people who want ordinary consumer goods and services will be able to afford them, while the labor force will not be as relatively monopolized by the wealthy.[184]

Effects on social welfare

In most western democracies, the desire to eliminate or reduce economic inequality is generally associated with the political left. One practical argument in favor of reduction is the idea that economic inequality reduces social cohesion and increases social unrest, thereby weakening the society. There is evidence that this is true (see inequity aversion) and it is intuitive, at least for small face-to-face groups of people.[185] Alberto Alesina, Rafael Di Tella, and Robert MacCulloch find that inequality negatively affects happiness in Europe but not in the United States.[186]

It has also been argued that economic inequality invariably translates to political inequality, which further aggravates the problem. Even in cases where an increase in economic inequality makes nobody economically poorer, an increased inequality of resources is disadvantageous, as increased economic inequality can lead to a power shift due to an increased inequality in the ability to participate in democratic processes.[187] According to Paul and Moser, countries with high income inequality and poor unemployment protections experience worse mental health outcomes among the unemployed.[188]

Capabilities approach

The capabilities approach – sometimes called the human development approach – looks at income inequality and poverty as form of "capability deprivation".[189] Unlike neoliberalism, which "defines well-being as utility maximization", economic growth and income are considered a means to an end rather than the end itself.[190] Its goal is to "wid[en] people's choices and the level of their achieved well-being"[191] through increasing functioning (the things a person values doing), capabilities (the freedom to enjoy functionings) and agency (the ability to pursue valued goals).[192]

When a person's capabilities are lowered, they are in some way deprived of earning as much income as they would otherwise. An old, ill man cannot earn as much as a healthy young man; gender roles and customs may prevent a woman from receiving an education or working outside the home. There may be an epidemic that causes widespread panic, or there could be rampant violence in the area that prevents people from going to work for fear of their lives.[189] As a result, income inequality increases, and it becomes more difficult to reduce the gap without additional aid.

Societal acceptance

A 2022 study published in Perspectives on Psychological Science found that in countries where neoliberal institutions have significant influence over policies, the psychology of those population are shaped to have both a higher tolerance of large levels of income inequality, and prefer it over more egalitarian outcomes.[193]

Arguments that economic inequality is not a problem

The majority of researchers who analyze economic inequality argue that today's levels are problematic and deserve some mitigation.[14] There are however, some who disagree, and feel that current levels of inequality are necessary because it encourages individuals to gain useful skills and take risks, thereby encouraging growth and innovation, which are necessary for progress.[14] Some have also argued that economic inequality is a natural and fair outcome in market economies, in which the rewards are distributed based on different economic contributions because individuals have different attitudes and talents.[14] Many who feel that economic inequality is not a significant issue are associated with conservative or libertarian think tanks funded by corporations and the wealthy[194] like The Heritage Foundation, the Manhattan Institute, the Cato Institute or the American Enterprise Institute, who may also feel that policies which would reduce inequality are direct attacks on their favored version of capitalism, laissez-faire capitalism.[14]: 1 In addition, some feel that economic inequality has not actually increased significantly.[14]

See also

- Accumulation of capital

- Anti-capitalism

- Aporophobia

- Class conflict

- Criticism of capitalism

- Cycle of poverty

- Donor Class

- Economic anxiety

- Economic migrant

- Economic security

- Equal opportunity

- Great Divergence, disproportionate economic advancement of Europe

- Human Development Index

- Income distribution

- Income inequality metrics

- Inequality for All

- International inequality

- List of countries by distribution of wealth

- List of countries by income equality

- List of countries by wealth per adult

- Occupy movement

- Paradise Papers

- Poverty reduction

- Public university

- Rent-seeking

- Social inequality

- Spatial inequality

- Tax haven

- Theories of poverty

- Wealth concentration

- Wealth distribution

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "GINI index (World Bank estimate) | Data". https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?view=map.

- ↑ Ventura, Luca (June 6, 2023). "World Wealth Distribution And Income Inequality 2022". https://www.gfmag.com/global-data/economic-data/wealth-distribution-income-inequality.

- ↑ Trapeznikova, Ija (2019). "Measuring income inequality". IZA World of Labor. doi:10.15185/izawol.462. https://wol.iza.org/articles/measuring-income-inequality.

- ↑ Human Development Reports. Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) . United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved: March 3, 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 "Introduction to Inequality" (in en). https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/Inequality/introduction-to-inequality.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bourguignon, François (2015). The Globalization of Inequality. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691160528. http://press.princeton.edu/titles/10433.html. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hung, Ho-Fung (2021). "Recent Trends in Global Economic Inequality". Annual Review of Sociology 47 (1): 349–367. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-090320-105810. ISSN 0360-0572.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Flaherty, Thomas M.; Rogowski, Ronald (2021). "Rising Inequality As a Threat to the Liberal International Order". International Organization 75 (2): 495–523. doi:10.1017/S0020818321000163. ISSN 0020-8183.

- ↑ "Parametric estimations of the world distribution of income". January 22, 2010. http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/4508.

- ↑ MacCulloch, Robert (2005). "Income Inequality and the Taste for Revolution". The Journal of Law and Economics 48 (1): 93–123. doi:10.1086/426881.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James A. (2005). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511510809. ISBN 978-0521855266. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/economic-origins-of-dictatorship-and-democracy/3F29DF90519971B183CAA16ED0203507.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Cederman, Lars-Erik; Gleditsch, Kristian Skrede; Buhaug, Halvard (2013). Inequality, Grievances, and Civil War. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139084161. ISBN 978-1107017429. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/inequality-grievances-and-civil-war/39F26D12EFEE2D7D621A59DF74DED496.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Neves, Pedro Cunha; Afonso, Óscar; Silva, Sandra Tavares (2016). "A Meta-Analytic Reassessment of the Effects of Inequality on Growth". World Development 78: 386–400. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.038.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Peterson, E. Wesley F. (December 2017). "Is Economic Inequality Really a Problem? A Review of the Arguments" (in en). Social Sciences 6 (4): 147. doi:10.3390/socsci6040147. ISSN 2076-0760.

- ↑ Hunt, Michael (2004). The World Transformed: 1945 to the Present. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 442. ISBN 978-0312245832. https://archive.org/details/worldtransformed0000hunt/page/442.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Gurría, Angel (December 5, 2011). Press Release for Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising (Report). OECD. doi:10.1787/9789264119536-en. ISBN 9789264111639. http://www.oecd.org/document/22/0,3746,en_21571361_44315115_49185046_1_1_1_1,00.html. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. OECD. 2011. doi:10.1787/9789264119536-en. ISBN 978-9264119536.[page needed]

- ↑ "Stock quotes, financial tools, news and analysis". MSN Money. http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/News/StudyRevealsOverwhelmingWealthGap.aspx.

- ↑ "Growth of millionaires in India fastest in world" . Thaindian News. June 25, 2008.

- ↑ Clifford, Catherine (January 26, 2021). "The '1%' are the main drivers of climate change, but it hits the poor the hardest: Oxfam report". CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/01/26/oxfam-report-the-global-wealthy-are-main-drivers-of-climate-change.html.

- ↑ Joseph, Stiglitz (March 1, 2022). "COVID Has Made Global Inequality Much Worse". Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/covid-has-made-global-inequality-much-worse/.

- ↑ Neate, Rupert (January 14, 2024). "World’s five richest men double their money as poorest get poorer". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2024/jan/15/worlds-five-richest-men-double-their-money-as-poorest-get-poorer.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Evolution of wealth indicators, USA, 1913-2019". World Inequality Database. 2022. https://wid.world/country/usa/.

- ↑ Kertscher, Tom; Borowski, Greg (March 10, 2011). "The Truth-O-Meter Says: True – Michael Moore says 400 Americans have more wealth than half of all Americans combined". PolitiFact. http://www.politifact.com/wisconsin/statements/2011/mar/10/michael-moore/michael-moore-says-400-americans-have-more-wealth-/.

- ↑ Moore, Michael (March 6, 2011). "America Is Not Broke". Huffington Post. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-moore/america-is-not-broke_b_832006.html.

- ↑ "The Forbes 400 vs. Everybody Else". michaelmoore.com. March 7, 2011. http://www.michaelmoore.com/words/must-read/forbes-400-vs-everybody-else.

- ↑ Pepitone, Julianne (September 22, 2010). "Forbes 400: The super-rich get richer". CNN. https://money.cnn.com/2010/09/22/news/companies/forbes_400/index.htm.

- ↑ Kristof, Nicholas (July 22, 2014). "An Idiot's Guide to Inequality". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/24/opinion/nicholas-kristof-idiots-guide-to-inequality-piketty-capital.html.

- ↑ Bruenig, Matt (March 24, 2014). "You call this a meritocracy? How rich inheritance is poisoning the American economy". Salon. http://www.salon.com/2014/03/24/death_of_meritocracy_how_inheritance_is_poisoning_the_american_economy/.

- ↑ "Inequality – Inherited wealth". The Economist. March 18, 2014. https://www.economist.com/blogs/buttonwood/2014/03/inequality.

- ↑ Neate, Rupert (November 8, 2017). "Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Warren Buffett are wealthier than poorest half of US". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/nov/08/bill-gates-jeff-bezos-warren-buffett-wealthier-than-poorest-half-of-us.

- ↑ Taylor, Matt (November 9, 2017). "The Paradise Papers Are Just a Glimpse at the Unreal Wealth Gap". Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/59yk75/the-paradise-papers-are-just-a-glimpse-at-the-unreal-wealth-gap.

- ↑ Neate, Rupert (October 26, 2017). "World's witnessing a new Gilded Age as billionaires' wealth swells to $6tn". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/oct/26/worlds-witnessing-a-new-gilded-age-as-billionaires-wealth-swells-to-6tn.

- ↑ Neate, Rupert (October 26, 2018). "World's billionaires became 20% richer in 2017, report reveals". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/oct/26/worlds-billionaires-became-20-richer-in-2017-report-reveals.

- ↑ Telford, Taylor (September 26, 2019). "Income inequality in America is the highest it's been since census started tracking it, data shows". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/09/26/income-inequality-america-highest-its-been-since-census-started-tracking-it-data-show.

- ↑ Novotný, Josef (2007). "On the measurement of regional inequality: Does spatial dimension of income inequality matter?". The Annals of Regional Science 41 (3): 563–80. doi:10.1007/s00168-007-0113-y.

- ↑ Mark Anderson (July 24, 2014). Jobs and social security needed as income inequality widens, UNDP warn. The Guardian . Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ↑ Norton, Michael I.; Ariely, Dan (2011). "Building a Better America—One Wealth Quintile at a Time". Perspectives on Psychological Science 6 (1): 9–12. doi:10.1177/1745691610393524. PMID 26162108.

- ↑ Hammar, Olle; Waldenström, Daniel (2020). "Global Earnings Inequality, 1970–2018". The Economic Journal 130 (632): 2526–2545. doi:10.1093/ej/ueaa109.

- ↑ Hellebrandt, Tomáš; Mauro, Paolo (2015). The Future of Worldwide Income Distribution. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- ↑ "Rising inequality affecting more than two-thirds of the globe, but it's not inevitable: new UN report". UN News. January 21, 2020. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/01/1055681.

- ↑ Improving job quality and reducing gender gaps are essential to tackling growing inequality. OECD, May 21, 2015.

- ↑ Era Dabla-Norris; Kalpana Kochhar; Nujin Suphaphiphat; Frantisek Ricka; Evridiki Tsounta (June 15, 2015). Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality : A Global Perspective. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ↑ Dunsmuir, Lindsay (October 11, 2017). "IMF calls for fiscal policies that tackle rising inequality". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/imf-g20-inequality/imf-calls-for-fiscal-policies-that-tackle-rising-inequality-idUSL2N1ML16B.

- ↑ Lawson, Max; Martin, Matthew (October 9, 2018). "The Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index 2018". Oxfam. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/commitment-reducing-inequality-index-2018.

- ↑ Kaplan, Juliana; Kiersz, Andy (December 7, 2021). "A huge study of 20 years of global wealth demolishes the myth of 'trickle-down' and shows the rich are taking most of the gains for themselves". Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-bad-is-inequality-trickle-down-economics-thomas-piketty-economists-2021-12.

- ↑ Elliott, Larry (December 7, 2021). "Global inequality 'as marked as it was at peak of western imperialism'". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/dec/07/global-inequality-western-imperialism-super-rich.

- ↑ "World Inequality Report 2022". https://wir2022.wid.world/.

- ↑ "Country Comparison: Distribution of family income – Gini index". CIA. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2172rank.html.

- ↑ OECD Framework for Statistics on the Distribution of Household Income, Consumption and Wealth. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. February 14, 2013. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/framework-for-statistics-on-the-distribution-of-household-income-consumption-and-wealth_9789264194830-en.

- ↑ Attanasio, Orazio P.; Pistaferri, Luigi (April 2016). "Consumption Inequality". Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (2): 3–28. doi:10.1257/jep.30.2.3. https://web.stanford.edu/~pista/JEP.pdf.

- ↑ "Consumption Inequality: What's in Your Shopping Basket? | JPMorgan Chase Institute". https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/cities-local-communities/insight-consumption-inequality.

- ↑ Neckerman, Kathryn M.; Torche, Florencia (July 18, 2007). "Inequality: Causes and Consequences". Annual Review of Sociology 33 (1): 335–357. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131755. ISSN 0360-0572. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131755.

- ↑ Piketty, Thomas (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press. ISBN 067443000X p. 571

- ↑ Stone, Jon (2016-05-27). "Neoliberalism is increasing inequality and stunting economic growth, the IMF says" (in en). https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/neoliberalism-is-increasing-inequality-and-stunting-economic-growth-the-imf-says-a7052416.html.

- ↑ Ostry, Jonathan D.; Loungani, Prakash; Furceri, Davide (June 2016). "Neoliberalism: Oversold?". Finance & Development. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/06/ostry.htm.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Stiglitz, Joseph E. (June 4, 2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future (Kindle ed.). Norton. p. 34. ISBN 9780393088694. https://archive.org/details/priceofinequalit00stig.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Kausik, B. N. (May 3, 2022). "Income Inequality, Cause and Cure". Challenge 65 (3–4): 93–105. doi:10.1080/05775132.2022.2046883. ISSN 0577-5132. https://doi.org/10.1080/05775132.2022.2046883.

- ↑ Parker, Kim; Fry, Richard. "More than half of U.S. households have some investment in the stock market". https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/25/more-than-half-of-u-s-households-have-some-investment-in-the-stock-market/.

- ↑ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia: Tax levied at a rate that increases as the quantity subject to taxation increases.

- ↑ Princeton University WordNet[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]: (n) progressive tax (any tax in which the rate increases as the amount subject to taxation increases)

- ↑ Alesina, Alberto; Dani Rodrick (May 1994). "Distributive Politics and Economic Growth". Quarterly Journal of Economics 109 (2): 465–90. doi:10.2307/2118470. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4551798.

- ↑ Hatch, Megan E.; Rigby, Elizabeth (2015). "Laboratories of (In)equality? Redistributive Policy and Income Inequality in the American States". Policy Studies Journal 43 (2): 163–187. doi:10.1111/psj.12094.

- ↑ Shlomo Yitzhaki (1998). "More than a Dozen Alternative Ways of Spelling Gini". Economic Inequality 8: 13–30. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDECINEQ/Resources/morethan2002.pdf.

- ↑ Chetty, Raj; Deming, David J.; Friedman, John N. (July 2023). "Diversifying Society's Leaders? The Determinants and Consequences of Admission to Highly Selective Colleges". Opportunity Insights. p. 2. https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/CollegeAdmissions_Nontech.pdf. Figure 3. "Ivy-Plus" refers to Ivy League schools plus others with similar prestige, rankings or selectivity.

- ↑ Becker, Gary S.; Murphy, Kevin M. (May 2007). "The Upside of Income Inequality". The America. http://www.american.com/archive/2007/may-june-magazine-contents/the-upside-of-income-inequality.

- ↑ Bosworth, Barry; Burtless, Gary; Steuerle, C. Eugene (December 1999). Lifetime Earnings Patterns, the Distribution of Future Social Security Benefits, and the Impact of Pension Reform (report no. CRR WP 1999-06). Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. p. 43. http://urban.org/uploadedpdf/412137-lifetime-earnings.pdf. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ↑ Shealy, Craig N. (November 1, 2009). "An Interview With Education for Sustainable Development "Young Voices": Beliefs and Values From the Next Generation of ESD Leaders". Beliefs and Values 1 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1891/1942-0617.1.2.135. ISSN 1942-0617. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1942-0617.1.2.135.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Baten, Jörg; Hippe, Ralph (2017). "Geography, land inequality and regional numeracy in Europe in historical perspective". Journal of Economic Growth.

- ↑ Schmitt, John and Ben Zipperer. 2006. "Is the U.S. a Good Model for Reducing Social Exclusion in Europe?" CEPR

- ↑ Michael Hiltzik (March 25, 2015). IMF agrees: Decline of union power has increased income inequality. Los Angeles Times . Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ↑ IMF: The last generation of economic policies may have been a complete failure. Business Insider. May 2016.

- ↑ Srikanth, Anagha (2020-12-17). "Huge new study shows trickle-down economics makes inequality worse, researchers say" (in en-US). https://thehill.com/changing-america/respect/poverty/530731-huge-new-study-shows-trickle-down-economics-makes-inequality/.

- ↑ Basu, Kaushik (January 6, 2016). "Is technology making inequality worse?". https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/is-technology-making-inequality-worse/.

- ↑ Rotman, David (October 21, 2014). "Technology and Inequality". MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/531726/technology-and-inequality/. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ Rothwell, Jonathan (November 17, 2017). "Myths of the 1 Percent: What's Putting People at the Top". The New York Times. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/17/upshot/income-inequality-united-states.html?action=click&module=MoreInSection&pgtype=Article®ion=Footer&contentCollection=The%20Upshot.

- ↑ Schor, Juliet B. (February 10, 2017). "Does the sharing economy increase inequality within the eighty percent?: findings from a qualitative study of platform providers". Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 10 (2): 263–279. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsw047. ISSN 1752-1378.

- ↑ Newton, Casey (May 23, 2013). "Temping fate: can TaskRabbit go from side gigs to real jobs?". https://www.theverge.com/2013/5/23/4352116/taskrabbit-temp-agency-gig-economy.

- ↑ Autor, David; Dorn, David; Katz, Lawrence F; Patterson, Christina; Van Reenen, John (May 1, 2020). "The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms*". The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (2): 645–709. doi:10.1093/qje/qjaa004. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ↑ Moll, Benjamin; Rachel, Lukasz; Restrepo, Pascual (2022). "Uneven Growth: Automation's Impact on Income and Wealth Inequality" (in en). Econometrica 90 (6): 2645–2683. doi:10.3982/ECTA19417. ISSN 0012-9682. https://www.econometricsociety.org/doi/10.3982/ECTA19417.

- ↑ "SOF/Heyman | The Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities". https://sofheyman.org/.

- ↑ "Economic Focus". The Economist (London): p. 81. April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Slaughter, Matthew J.; Swagel, Phillip (September 1997). "Does Globalization Lower Wages and Export Jobs?" (in en-US). Economic Issues. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/issues11/.

- ↑ Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1786090034.

- ↑ OECD. OECD Employment Outlook 2008 – Statistical Annex . OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 358.

- ↑ "Are Women Earning More Than Men?". Forbes. May 12, 2006. https://www.forbes.com/ceonetwork/2006/05/12/women-wage-gap-cx_wf_0512earningmore.html.

- ↑ Lukas, Carrie (April 3, 2007). "A Bargain At 77 Cents To a Dollar". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/02/AR2007040201262.html.

- ↑ Weinberg, Daniel H (May 2004). "Evidence From Census 2000 About Earnings by Detailed Occupation for Men and Women". https://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/censr-15.pdf.

- ↑ Habibov, Nazim (2012). "Income inequality and its driving forces in transitional countries: evidence from Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia". Journal of Comparative Social Welfare 28 (3): 209–211. doi:10.1080/17486831.2012.749504. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271672769.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:3 - ↑ Bloome, D.; Western, B. (December 1, 2011). "Cohort Change and Racial Differences in Educational and Income Mobility". Social Forces 90 (2): 375–395. doi:10.1093/sf/sor002. ISSN 0037-7732.

- ↑ Herring, Cedric; Conley, Dalton (March 2000). "Being Black, Living in the Red: Race, Wealth, and Social Policy in America". Contemporary Sociology 29 (2): 349. doi:10.2307/2654395. ISSN 0094-3061.

- ↑ Vallejo, Jody Agius (December 2010). "Generations of exclusion: Mexican Americans, assimilation and race". Latino Studies 8 (4): 572–574. doi:10.1057/lst.2010.45. ISSN 1476-3435.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Bowles, Samuel; Gintis, Herbert (August 1, 2002). "The Inheritance of Inequality". Journal of Economic Perspectives 16 (3): 3–30. doi:10.1257/089533002760278686. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, Debopam; Mazumder, Bhashkar (2010). "A Nonparametric Analysis of Black-White Differences in Intergenerational Income Mobility in the United States". Quantitative Economics 2 (3): 335–379. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1066819. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ↑ Hertz, Tom (December 31, 2009), Bowles, Samuel; Gintis, Herbert; Osborne Groves, Melissa, eds., "Chapter Five. Rags, Riches, and Race The Intergenerational Economic Mobility of Black and White Families in the United States", Unequal Chances (Princeton: Princeton University Press): pp. 165–191, doi:10.1515/9781400835492.165, ISBN 978-1400835492

- ↑ de Ferranti, David; Perry, Guillermo E.; Ferreira, Francisco; Walton, Michael (2004). Inequality in Latin America. doi:10.1596/0-8213-5665-8. ISBN 978-0821356654.

- ↑ Bossuroy, Thomas; Cogneau, Denis (April 18, 2013). "Social Mobility in Five African Countries". Review of Income and Wealth 59: S84–S110. doi:10.1111/roiw.12037. ISSN 0034-6586.

- ↑ Peil, Margaret (January 1990). "Intergenerational mobility through education: Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe". International Journal of Educational Development 10 (4): 311–325. doi:10.1016/s0738-0593(09)90008-6. ISSN 0738-0593.

- ↑ Hnatkovska, Viktoria; Lahiri, Amartya; Paul, Sourabh B. (2013). "Breaking the Caste Barrier: Intergenerational Mobility in India". Journal of Human Resources 48 (2): 435–473. doi:10.1353/jhr.2013.0012. ISSN 1548-8004.

- ↑ Korpi, Walter; Palme, Joakim (1998). "The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: Welfare State Institutions, Inequality, and Poverty in the Western Countries". American Sociological Review 63 (5): 661–687. doi:10.2307/2657333. ISSN 0003-1224. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2657333.

- ↑ pp. 384 Table 12.2, U.S. university endowment size vs. real annual rate of return

- ↑ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (June 4, 2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future (pp. 30–1, 35–6). Norton. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (June 4, 2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future (p. 32). Norton. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ James K. Galbraith, Inequality and Instability: A Study of the World Economy Just before the Great Crisis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- ↑ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (June 4, 2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future, p. 334. Norton. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Stevens, Harry (1 March 2023). "The United States has caused the most global warming. When will China pass it?". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/interactive/2023/global-warming-carbon-emissions-china-us/.