Expulsion of Poles by Germany

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

Prussian deportations of 1885–1890 as shown on a contemporary painting by Konstanty Górski | |

Expulsion of Poles from Reichsgau Wartheland following the Invasion of Poland (1939). Families led to the trains under German escort, as part of Nazi German ethnic cleansing of annexed Poland. | |

| Location | German-controlled territories |

|---|---|

| Type | Ethnic cleansing |

| Cause | Lebensraum, anti-Polish sentiment |

| Patron(s) | Frederick the Great, Otto von Bismarck, Adolf Hitler |

| Outcome | Expulsion of 325,000 poles .[1] |

The Expulsion of Poles by Germany was a prolonged anti-Polish campaign of ethnic cleansing by violent and terror-inspiring means lasting nearly half a century. It began with the concept of Pan-Germanism developed in the early 19th century and culminated in the racial policy of Nazi Germany that asserted the superiority of the Aryan race. The removal of Poles by Germany stemmed from historic ideas of expansionist nationalism. It was implemented at different levels and different stages by successive German governments. It ended with the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945.[2]

The partitions of Poland had ended the existence of a sovereign Polish state in the 18th century. With the rise of German nationalism in mid 19th century, Poles faced increasing discrimination on formerly Polish lands. The first mass deportation of 30,000 Poles from territories controlled by the German Empire took place in 1885. While the ideas of expelling Poles can be found in German political discourse of the 19th century, these ideas matured into nascent plans advocated by German politicians during the First World War, which called for the removal of the Polish population from Polish territories first annexed by the Russian Empire during partitions and then by Germany.[3] Before and after the 1939 invasion of Poland the Nazis exploited these ideas when creating their Lebensraum concept of territorial aggression.[3] Large-scale expulsions of Poles occurred during World War II when Nazi Germany started the Generalplan Ost campaign of ethnic cleansing in all Polish areas occupied by, and formally annexed to Nazi Germany. Although the Nazis were not able to fully implement Generalplan Ost due to the war's turn, up to 2 million Poles were affected by wartime expulsions with additional millions displaced or murdered.

Background

Poles had constituted one of the largest minorities in the German Empire since its creation in 1871. This was a result of the earlier acquisitions made by Prussia, the state that initiated the Unification of Germany. The Electorate of Brandenburg (later Kingdom of Prussia), with its capital in Berlin after 1451, acquired historic lands with significant Polish population in a series of military operations,[3] and, in the second half of the 18th century, had seized western territories of the Polish Kingdom by taking part in the Partitions of Poland and the Silesian Wars with Austria.

The idea of pan-Germanism, demanding the unification of all Germans in one state, including the German diaspora east of the imperial border, grew out of Romantic nationalism. Some pan-Germanists believed that Germans were ethnically superior to other peoples — including Slavs, whom they viewed as inferior to the German "race" and culture. The Nazi concept of Lebensraum in turn demanded "living space" for German people, claiming overpopulation of Germany and alleged negative traits of heavy urbanisation in contrast to agricultural settlement. The desired territories were to be taken particularly from Poland. Both pan-Germanism and Lebensraum theory viewed Poles as an obstacle to German hegemony and prosperity as well as future expansion of the German state.[3]

German Empire

In the territories annexed during the Partitions of Poland, German authorities sought to limit the number of ethnic Poles by their forced Germanisation and by a new wave of settlement by German colonists at their expense.[3] Beginning with the Kulturkampf, laws were enacted to restrict Polish culture, religion, language, and rights to property. Bismarck initiated the Prussian deportations of 1885–1890, which affected some 30,000 Poles and Jews living in Germany who did not have German citizenship. This is described by E.J. Feuchtwanger as one of the precedents to modern policies of ethnic cleansing.[4] In 1887 Bernhard von Bülow, the future Chancellor of the German Empire, advocated expelling Poles by force from territories which were Polish-inhabited and slated to become part of Germany.[5]

In 1908, Germany legalized the eviction of Poles from their properties under pressure from pan-German nationalist groups who hoped this law would be used to reduce the number of Poles in the East.[3]

World War I

In August 1914 the German imperial army bombed and burned down the city of Kalisz, chasing out tens of thousands of its Polish citizens. However, during World War I, Germany had a frantic need for extra manpower in the East and hoped to tap into the reservoir of military volunteers among the Poles by making promises of a future independent Polish state. This initiative (led by Bethmann) failed, producing only "a dribble of volunteers" in 1916, but it was a commitment very hard to retract. There were numerous mistakes made, such as the Oath Crisis, caused by poor wording of the oath of the Polish soldiers, which caused consternation among many Polish volunteers. In general, opinions of the German occupiers were mixed, between those who hoped that the Germans would set up a new Polish state, and those who feared German domination. In any case, successful attacks by the Russian army, such as the 'Brusilov offensive', forced Germany to consider a quasi independent buffer state between the two empires, hopefully set up only in the former Russian Poland and linked to Germany by its own military means.[6] The idea of reconstituting Congress Poland for the Poles after the war, was a cynical ploy which stemmed from a desire to push Russia's frontiers further East with the least amount of German effort.[7] In reality, Germany planned to annex about 30,000 km2 from former Congress Poland for German colonisation.[3] Most of the Polish population of those territories (about 2,000,000 people) was to be expelled into a small Polish puppet state.[3] The remaining population was to be used as agricultural labour for new German colonists.[3]

World War II

With the occupation of Poland following the German invasion of the country, Nazi policies were enacted upon its Polish population on an unprecedented scale. According to Nazi ideology Poles, as Untermenschen, were seen as fit only for slavery and for further elimination in order to make room for the Germans. Adolf Hitler had plans for extensive colonisation of territories in the east of the Third Reich. Poland, itself, would – according to well documented German plans – have been cleared of Polish people altogether, as 20 million or so would have been expelled eventually. Up to 3 or 4 million Polish citizens (all peasants) believed to be descendants of German colonists and migrants and therefore considered "racially valuable" would be Germanised and dispersed among the German population.[8] Nazi leadership hoped that through expulsions to Siberia, famine, mass executions, and slave labour of any survivors, the Polish nation would be eventually completely destroyed.[9]

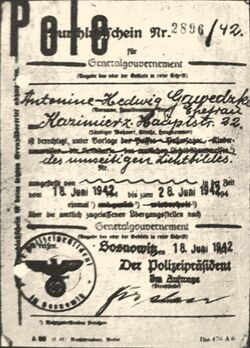

World War II expulsions took place within two specific territories: one area annexed to Reich in 1939 and 1941, and another, the General Government, precursor to further expansion of German administrative settlement area. Eventually, as Adolf Hitler explained in March 1941, the General Government would be cleared of Poles, the region would be turned into a "purely German area" within 15–20 years and in place of 15 million Poles, 4–5 million Germans would live there, and the area would become "as German as the Rhineland.[10]

Expulsions from Polish territories annexed by Nazi Germany

The Nazi plan to ethnically cleanse the territories occupied by Germany in Eastern Europe during World War II, was called the Generalplan Ost (GPO). Germanisation began with the classification of people suitable as defined on the Nazi Volksliste.[11] About 1.7 million Poles were deemed Germanizable, including between one and two hundred thousand children who were taken from their parents.[12] For the rest, expulsion was carried out.

These expulsions were carried out so abruptly that ethnic Germans being resettled there were given homes with half-eaten meals on tables and unmade beds where small children had been sleeping at the time of expulsion.[13] Members of Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls were assigned the task of overseeing such evictions to ensure that the Poles left behind most of their belongings for the use of the settlers.[14] According to Czesław Łuczak, Germans expelled the following numbers of Poles from territories annexed to the Reich in the period of 1939–1944:

| Name of territory | Number of displaced Poles |

|---|---|

| Warthegau region | 630,000 |

| Silesia | 81,000 |

| Pomerelia | 124,000 |

| Białystok | 28,000 |

| Ciechanów | 25,000 |

| So called "Wild expulsions" of 1939 (Pomerelia mostly) | 30,000 – 40,000 |

| Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany (total) | 918,000 – 928,000 |

| Zamość region | 100,000 – 110,000 |

| General Government (Proving grounds) | 171,000 |

| Warsaw (after Warsaw uprising) | 500,000 |

| Grand total, on all occupied Polish territories | 1,689,000 – 1,709,000 |

Combined with "wild expulsions", in four years 923,000 Poles were ethnically cleansed from territories Germany annexed into the Reich.[16]

Expulsions from General Government

Within the territories of the German protectorate called General Government there were two main areas of expulsions committed by the German state. The protectorate itself was seen as temporary measure, and served as a concentration camp for Poles to perform hard labour furthering German industry and war effort. Eventually it was to be cleared of Poles also.

Zamość

Some 116,000 Poles were expelled from the Zamość region as part of Nazi plans for establishment of German colonies in the conquered territories. Zamość itself was to be renamed Himmlerstadt, later changed to Pflugstadt (Plough City), which was to symbolise the German "Plow" that was to "plough" the East. Additionally, almost 30,000 children were kidnapped by German authorities from their parents for potential Germanisation.[16] This led to massive resistance (see Zamość Uprising).

Warsaw

In October 1940, 115,000 Poles were expelled from their homes in central Warsaw to make room for the Jewish Ghetto, constructed there by German authorities. (Jews were then expelled from their homes elsewhere and forced to move into the Ghetto.) When the Warsaw Uprising failed, 500,000 people were expelled from the city alone as punishment by German authorities.[16]

Demographic estimates

It is estimated that between 1.6 and 2 million people[17] were expelled from their homes during the German occupation of Poland. The Nazi German organized expulsions—by themselves—affected 1,710,000 Poles directly.[16] New estimates by Polish historians give the number of 2.478 million people expelled.[1] Additionally, 2.5 to 3 million Poles were taken from Poland to Germany as slave labourers to support the Nazi war effort.[9] These numbers do not include people arrested by the Germans and sent to Nazi concentration camps.[17]

In many instances, Poles were given between 15 minutes and 1 hour to collect their personal belongings (usually no more than 15 kilograms per person) before they were removed from their homes and transported east (see: deportations) On top of that about 5 million Poles were sent to German labor and concentration camps.[18] A total of about 6 million Polish citizens were killed during the war, of which approximately half were Jews or of Jewish descent.[19][20] All these actions resulted in significant changes in Polish demographics at the end of the war.[19]

See also

- Drang nach Osten (Drive towards the East)

- Expulsion of Germans after World War II

- Generalplan Ost, Hitler's "new order of ethnographical relations"

- Lebensraum (Living space), the primary political concept used by the Nazis to "justify" the conquest of territory in Poland and Eastern Europe

- Nazi propaganda

- Pacification operations in German-occupied Poland

- Prussian deportations of Poles and Jews in 1885-1890

- Repatriation of Poles (1944–1946)

- World War II evacuation and expulsion

- Chronicles of Terror

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nowa Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 2004, pages 811-812 (volume 8), s. 709 (volume 6). ISBN 83-01-14179-4.

- ↑ Polska Akademia Nauk (Polish Academy of Sciences), Historia Polski, Vol. III 1850/1864-1918, Part 2 1850/1864-1900, edited by Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warsaw 1967.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Imannuel Geiss, Der polnische Grenzstreifen 1914-1918. Ein Beitrag zur deutschen Kriegszielpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg, Hamburg/Lübeck 1960

- ↑ E.J. Feuchtwanger, "Bismarck", Routledge 2002

- ↑ Herbert Arthur Strauss, "Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism 1870-1933-39 Germany - Great Britain-France", Walter de Gruyter 1993

- ↑ Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy By David Stevenson. Page 108 Accessed 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Germany and Eastern Europe edited by Keith Bullivant, Geoffrey Giles, Walter Pape. Page 28 Accessed 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Janusz Gumkowski and Kazimierz Leszczynski, "Hitler's War; Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe", 1961, (in) Poland under Nazi Occupation, Polonia Publishing House, Warsaw, pp. 7-33, 164-178.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wojciech Roszkowski, Historia Polski 1914–1997, Warsaw 1998

- ↑ Berghahn, Volker R. (1999), "Germans and Poles 1871–1945", Germany and Eastern Europe: Cultural Identities and Cultural Differences (Rodopi): 15–34, ISBN 9042006889, https://books.google.com/books?id=j6VCNno2DVMC&q=Volker+R.+Berghahn+1999&pg=PA15

- ↑ Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, p543 ISBN 0-393-02030-4

- ↑ Pierre Aycoberry, The Social History of the Third Reich, 1933-1945, p 228, ISBN 1-56584-549-8

- ↑ Lynn H. Nicholas, Cruel World: The Children of Europe in the Nazi Web p. 213-4 ISBN 0-679-77663-X

- ↑ Walter S. Zapotoczny, "Rulers of the World: The Hitler Youth"

- ↑ Czesław Łuczak, "Polityka ludnościowa i ekonomiczna hitlerowskich Niemiec w okupowanej Polsce" Wydawnictwo Poznańskie Poznań 1979 ISBN 832100010X

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Zygmunt Mańkowski; Tadeusz Pieronek; Andrzej Friszke; Thomas Urban (panel discussion), "Polacy wypędzeni", Biuletyn IPN, nr5 (40) May 2004 / Bulletin of the Institute of National Remembrance (Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej), issue: 05 / 2004, pages: 628, [1]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Poles: Victims of the Nazi Era" at US Holocaust Memorial Museum

- ↑ Dr Waldemar Grabowski, IPN Centrala (2009-08-31). "Straty ludności cywilnej". Straty ludzkie poniesione przez Polskę w latach 1939-1945. Bibula – pismo niezalezne. http://www.bibula.com/?p=13530. "Według ustaleń Czesława Łuczaka, do wszelkiego rodzaju obozów odosobnienia deportowano ponad 5 mln obywateli polskich (łącznie z Żydami i Cyganami). Z liczby tej zginęło ponad 3 miliony."

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Poland's World War II casualties.

- ↑ "Holocaust: Five Million Forgotten: Non Jewish Victims of the Shoah," see also: The Forgotten Holocaust, by Richard C. Lukas, University Press of Kentucky; and The Jews and the Poles in World War II by Stefan Korbonski, Hippocrene Books.

Bibliography

- Maria Rutowska, "Wysiedlenia ludności polskiej z Kraju Warty do Generalnego Gubernatorstwa 1939-1941" Instytut Zachodni, Poznań 2003,ISBN 83-87688-42-8

- Czesław Łuczak, Polityka ludnościowa i ekonomiczna hitlerowskich Niemiec w okupowanej Polsce, Wyd. Poznańskie, Poznań 1979 ISBN 83-210-0010-X

- Czesław Łuczak, "Położenie ludności polskiej w Kraju Warty 1939 - 1945", Wydawnictwo Poznańskie 1987

- Czesław Madajczyk, Generalny Plan Wschodni: Zbiór dokumentów, Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce, Warsaw, 1990

- Czesław Madajczyk, Generalna Gubernia w planach hitlerowskich. Studia, PWN, Warsaw. 1961

- Czesław Madajczyk, Polityka III Rzeszy w okupowanej Polsce, Warsaw, 1970

- Andrzej Leszek Szcześniak, Plan Zagłady Słowian. Generalplan Ost, Polskie Wydawnictwo Encyklopedyczne, Radom, 2001

- Piotr Szubarczyk (IPN Gdańsk), "Umacnianie niemczyzny" na polskim Pomorzu, Nasz Dziennik, 03.09.2009

- L. Chrzanowski, "Wypędzenia z Pomorza," Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej”, 2004, nr 5 (40), ss. 34 – 48.

- W. Jastrzębski, Potulice. Hitlerowski obóz przesiedleńczy i pracy, Bydgoszcz 1967.

External links

KSF

KSF