Friends of the Indian

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

The Friends of the Indian was a group that pushed for Indian assimilation during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After dealing with "the Indian problem" through treaties, removal, and reservations, the Federal Government of The United States moved toward a method that is now referred to as assimilation.[1] The Friends of the Indian group, which was largely connected to and intertwined with the Office of Indian Affairs within the Federal Government[1] presented themselves as speaking on behalf of Native Americans who they viewed as unable to speak for themselves.[2] They claimed that the best course of action for Native Americans was to assimilate them into the larger American culture, rather than allowing them to maintain their existing native cultures. The Friends used many tactics to push for said assimilation. Some went and lived with tribes, or contributed to the new discipline of anthropology to establish themselves as experts and push for cultural change.[3] Some wrote books and essays about the poor treatment of Indians they had seen in the past and how this treatment might be improved.[1] Others lobbied for legislative change through the Federal Government. The Friends of the Indian played a large role in the assimilation of American Indians by pushing for the passing of the Dawes Act,[1] the Indian Citizenship Act,[4] the creation and use of Indian boarding schools, and the continuation of an expectation that Indians could not speak for themselves.

The "Indian problem"

Since the beginning of America, the United States government faced what it has called the "Indian problem" or the "Indian question." The government wanted the land that Native Americans inhabited for themselves and used several different approaches to get it.[1] Since 1787, interactions between Native peoples and the Federal Government have gone through what can be divided into six distinct phases: agreements between equals (1787-1828), removal and reservations (1828-1887), allotment and assimilation (1887-1934), reorganization (1928-1953), termination and relocation (1953-1968), and self-determination (1968–present).[5] The Friends of the Indian were primarily active during the period of allotment and assimilation from 1887 to 1934.

Indian assimilation

The goal of Indian assimilation was to remove the differences that separated Native Americans from the rest of the country by separating Native people from their culture and replacing it with white American culture. The Friends of the Indian, along with other activist groups claimed that the "Indian problem" had been handled wrongly in the past which had led to the mistreatment of American Indians. Assimilation was their proposal on how to deal with Natives more humanely and ethically. Many members of the Friends of the Indian had previously worked in the Office of Indian Affairs and knew of Indian mistreatment firsthand. Others still worked for the Federal Government.[1] They viewed Indian removal and the reservation system as immoral and believed that Indians would be better off being fully integrated into the rest of American culture, rather than remaining distinct.[2][4] While there were some whose motives were to help Native people, many who supported assimilation were after Native lands and wanted Native people out of the way of the white settlers who were moving West in large numbers during this period.[4] However, assimilation was presented as a more benevolent and ethical way to deal with Indians than had been used in the past. The tactics of assimilation focused on dismantling reservations, making Indigenous people into American citizens, and white-washing Native children. Importantly, assimilation policies were created largely without input from Native Americans, as the Friends of the Indian and other white activist groups considered themselves more qualified to speak on behalf of Natives than Natives themselves were.[2]

The process of assimilation proved devastating for Native Americans.[1] It strengthened the government's control over Native communities, diminished the amount of land they controlled by nearly 90%,[2] and essentially put an end to the way of life that had existed among them for hundreds of years.[4]

Cultural efforts of assimilation

Mission schools

Religious schools were opened in the early 1800s.[6] White Americans believed that their way of life was the correct way and would eliminate the problems of poverty that the Indigenous people faced in their reduced lands.[6] To help, Christian churches opened mission schools on the reservations to teach the Indigenous children to live like the European-American settlers. However, many settlers thought that this form of education was not effective enough in changing the children. Some believed that taking the children far from home would force them to accept what the settlers saw as the better way of life. This led to the creation of Indian Boarding Schools.[6]

Boarding schools

In their efforts toward Indian assimilation, the Friends of the Indian were one of the major proponents of Indian boarding schools.[7] Indian boarding schools were created with the express purpose of erasing Native culture; to "kill the Indian, and save the man."[5] The first off-reservation boarding school was created by Richard Pratt in 1879 at a former military facility in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.[5][8] While many white Americans believed that Native people were inherently inferior to white people, Pratt believed that American Indians were being limited by their culture and specifically by the reservation system.[8] Consequently, he saw the solution as removing Native children from reservations to help them reach their full potential. This generated a large movement aimed at removing American Indian children from reservations and placing them into boarding schools which were largely modeled after the school at Carlisle.[9] These efforts were helped by the support and lobbying efforts of the Friends of the Indian, who had extensive influence in the Federal government.[1] While most were sponsored by the US government, some were created through religious institutions, and others were privately run.[8]

Though experiences differed between boarding schools, most children who attended them were forced to cut their long hair, had their Native clothes exchanged for European-style clothing, were given English names, were discouraged from speaking their native languages, and were trained in skills or vocations that would make them successful in the economy outside of reservations. Essentially, they had their native culture removed and replaced with whiteness.[8] In addition to the attempts at disconnecting Indigenous children from their culture, the environment and living conditions the children lived in were very poor.[10] Within many of the schools, disease spread quickly and harsh physical punishment was a daily occurrence. When the children returned to their families, some children were able to make use of their learned skills while others had a difficult time returning to their former lifestyle, some even being rejected by their families.[10]

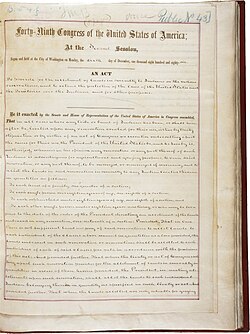

The Dawes Act

One of the main achievements of the Friends of the Indian was the passage of the Dawes Act (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887). This act allowed the U.S. Federal Government to survey Indian lands and divide Indian reservations into individually owned plots of land which would then be distributed to individual Indians.[1] The bill further stated that if Indians proved they could cultivate and improve upon the land they were allotted and denounced tribal allegiances, they would be granted U.S. citizenship.[4] This allotment of land was part of the process of assimilation and was done to discourage communalism, a key facet of most Native cultures which the government perceived as uncivilized, and encourage individualism.[4] The Friends and other advocate groups saw several positives in this legislation: it would break the social unit of Native tribes, encourage more self-reliance and private enterprise, reduce the cost to the Federal Government of administrating over Indians, create more funding for boarding schools, and clear land for white settlement.[1]

As a result of the Dawes Act, 100 million acres of reservation land were transferred from American Indians to white control.[2] It reaffirmed the colonizing relationship that the U.S. had with Native peoples, further homogenized distinct Native groups, and stripped them of their land and the many cultural traditions tied to it.[4] Importantly, this act was created and passed without input or assent from Native peoples or tribes.[1]

Questions surrounding Indian allotment

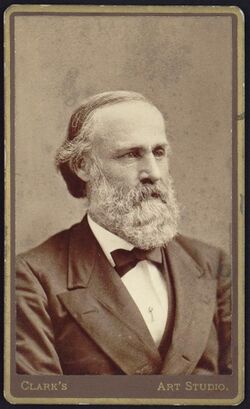

Henry Dawes and the Friends of the Indians

Senator Henry Dawes (1816-1903) of Massachusetts was an active member of the Friends of the Indian.[1] He introduced the bill that would eventually become the General Allotment Act into the Senate.[4] Following this, he and other paid lobbyists in Washington, including other Friends, pressured legislators for it to be passed.[1] Dawes argued the case for the bill to the Senate by claiming that labor could lead Natives "out from the darkness and into the light" to "citizenship." He believed it was the job of the government to prepare Natives for citizenship by teaching them to own and farm land like American citizens.[4]

Alice Fletcher and the Friends of the Indians

One prominent figure when it came to the assimilation of Indigenous people was Alice Cunningham Fletcher (1838-1923). Fletcher was an American anthropologist and a pioneering ethnologist.[7] She assisted in the writing of the Dawes General Allotment Act of 1887[7] and seemed to genuinely believe that assimilation was what was best for Native Americans.[11] Along with having a connection to white policymakers in Washington, D.C., Fletcher was also involved with several reform groups, one of which was the Friends of the Indian.[7] While being a part of the Friends of the Indian, Fletcher continued to support Native assimilation. Due to her connections to policymakers in Washington, she was hired as an allotting agent in March 1883 to carry out the land allotment program among the Omaha Indians, a task for which she was paid 5 dollars per day.[11] She did this job for 13 months, and then spent 7 years in Washington, D.C., after which she continued her work with the Omaha.[11] She spent the majority of her years as an allotting agent living among the Nez Perce tribe where she made 1,908 allotments before her departure on 13 September 1892.[7]

Indian Citizenship Act

Throughout the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, there was a debate over whether Native peoples should have the rights of American citizens. It was believed by many that until an American Indian was assimilated into the broader American culture, he was not a "person."[12] Estelle Reel, the Superintendent of U.S. Indian Schools from 1898 to 1910 had many opinions on this matter.[13] Reel believed that the Indigenous people were of a "lesser" race which greatly influenced the curriculum taught in the schools.[13] Uniform Course of Study displayed the importance of teaching sewing to the American Indians in federal schools.[13] Reel believed this would help the primitive children become more civilized. She promoted the idea that race determined one's capacities and if a society was one of "civilized" or "barbaric" people.[13]

The Indian Citizenship Act was passed in 1924 and granted citizenship to any Native American born within the United States. Though many American Indians had already become citizens through the provisions of the Dawes Act and other similar legislation, activist groups such as the Friends of the Indian and the Indian Rights Association began lobbying for extending citizenship to all Natives in the years following World War I in response to Native efforts in the war.[1]

Again, Native groups were not consulted before this act was passed, and though many of them were happy with the act,[4] many were not.[1] And though this legislation did grant certain rights and privileges to Native peoples, it came largely at the expense of their autonomy and authority to govern themselves.[4] It also further complicated their identity as Indigenous peoples, mixing and sometimes replacing it with an American identity.[4]

Native reactions

While every tribe was affected by the actions of the United States government, the responses varied between groups. The Ojibwe tribe at Red Lake consisted of a majority of warrior people due to continuous warfare in their past.[1] In 1886, the United States government visited in an attempt to relocate other Ojibwe people there. However, the Red Lake leaders were prepared and responded by rejecting the commissioner's proposal.[1] The chiefs were fervent in their response that the Red Lake territory was theirs. After a lot of back and forth, the Red Lake Ojibwe lost millions of acres. However, they were never subjected to the allotment. Other Indigenous peoples adopted the way of life of white Americans.[3] Sarah Winnemucca, for example, was a Paiute woman who learned how to read and write and adopted European fashion trends. Winnemucca avoided assimilating, and instead, like many others, found a way to mix the two identities and cultures of the Paiute and the European-Americans.[3]

Due to the Dawes Act, several tribal nations would be forced to live together and blend culturally.[4] These tribes' active communication and unification slowed the implementation of the Dawes act. The Native voice was also influential in addressing duality when it came to United States citizenship. The contradictions of the government were more often exposed due to the individual tribes working together under one voice.[4]

Indian Reorganization Act of 1934

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 advocated for by Native people, but almost singlehandedly written and passed through the efforts of John Collier, essentially reversed the Dawes Act. It ended white claims to Native lands through allotment, created ways for lost land to be returned to Indigenous groups, created structures to incorporate new lands, and largely brought Indigenous peoples out from under the hand of the Office of Indian Affairs.[4] In a change from previous patterns of legislation being forced on Indians without their consent, each reservation was allowed to vote on whether or not the Reorganization Act would apply to them.[1] The results of the Act were mixed, with some tribes benefiting from it, and others becoming subject to subtle forms of coercion due to its loopholes.[1]

See also

- Dawes Act

- Indian Citizenship Act

- Henry L. Dawes

- Alice Cunningham Fletcher

- Indian Reorganization Act

- Indian Rights Association

- American Indian boarding schools

- Cultural assimilation of Native Americans

- Sarah Winnemucca

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 Truer, David (2019). The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present. New York: Riverhead Books. pp. 114–199. ISBN 9780399573194.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Churchill, Ward (1992). Jaimes, M. Annette. ed. Fantasies of the Master Race (2nd ed.). Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press. pp. 134. ISBN 0-9628838-7-5.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Senier, Siobhan (2001). Voices of American Indian Assimilation and Resistance: Helen Hunt Jackson, Sarah Winnemucca, and Victoria Howard. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3293-0.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 Black, Jason Edward (2015). American Indians and the Rhetoric of Removal and Allotment. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62846-196-1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Phan, Loan T. (2018). "Ten Stages of American Indian Genocide". Interamerican Journal of Psychology 52 (1): 25–44. https://journal.sipsych.org.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Littlefield, Holly (2001). Children of the Indian Boarding Schools: 1879 to Present. Minneapolis: Carolrhoda Books, Inc.. ISBN 1-57505-467-1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Fletcher, Alice C.; Tonkovich, Nicole (2016). Dividing the Reservation: Alice C. Fletcher's Nez Perce Allotment Diaries and Letters, 1889-1892. Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press. pp. 1–21. ISBN 9780874223446.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Coleman, Michael C. (1993). American Indian Children at School, 1850-1930. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 0-87805-616-5.

- ↑ "The West: The Geography of Hope: Friends of the Indian". 2001. http://www.shoppbs.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/seven/friendsofindian.htm.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Stout, Mary A. (2012). Native American Boarding Schools. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-38676-3.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Mark, Joan (1988). A Stranger in Her Native Land: Alice Fletcher and the American Indians. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 45–138. ISBN 0-8032-3128-8.

- ↑ Oskison, John M. (1995). "Friends of the Indian". https://eds.s.ebscohost.com/eds/ebookviewer/ebook?sid=17164afa-cc6f-43d1-b2d7-3687fe62f7f5%40redis&vid=0&format=EB.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Lomawaima, K. Tsianina (1996). "Estelle Reel, Superintendent of Indian Schools, 1898-1910: politics, curriculum, and land.". Journal of American Indian Education 35 (3): 5–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24398294. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

|

KSF

KSF