Libian

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

Libian (simplified Chinese: 隶变; traditional Chinese: 隸變; pinyin: lìbiàn; literally: 'clerical change') refers to the natural, gradual, and systematic simplification of Chinese characters over time during the 2nd Century BC, as Chinese writing transitioned from seal script character forms to clerical script characters during the early Han dynasty period, through the process of making omissions, additions, or transmutations of the graphical form of a character to make it easier to write.[1] Libian was one of two conversion processes towards the new clerical script character forms, with the other being liding, which involved the regularisation and linearisation of character shapes.

Process

The earlier seal script characters were complicated and inconvenient to write; as a result, lower-level officials and clerics (隸; lì) gradually simplified the strokes, and transitioned from writing with bowed ink brushes to using straight ink brushes, which both improved ease of writing.

The complexity of characters can be reduced in one of four ways:[2]

- Modulation (調變): The replacement of character components with an unrelated component. For example, the ancient bronze form of 射 (shè; "to shoot an arrow") was written as

, however the left-side component became replaced with 身 ("body") during the transition to clerical script writing.

, however the left-side component became replaced with 身 ("body") during the transition to clerical script writing. - Mutation (突變): Some characters undergo modulation so suddenly that no clue hinting at the original form can be found in the new form. For example, the transition from the seal script character

("spring") to the clerical (and by extension, modern) form 春 completely drops any hints of the original 芚 component, instead replacing it with 𡗗 which seemingly has zero basis in relation to the original component.

("spring") to the clerical (and by extension, modern) form 春 completely drops any hints of the original 芚 component, instead replacing it with 𡗗 which seemingly has zero basis in relation to the original component. - Omission (省變): The complete omission of a character component. For example, the clerical script form of 書 (shū, Old Chinese: /*hlja/; "to write") completely omits the phonetic component 者 (Old Chinese: /*tjaːʔ/) at the bottom of the seal script form

.

. - Reduction (簡變): Simplifies character components to a form with fewer strokes. For example, the ancient form of

/僊 (xiān, Old Chinese: /*sen/; "celestial being") had the complex phonetic component 䙴 (Old Chinese: /*sʰen/) simplified into 山 (Old Chinese: /*sreːn/), creating the clerical form 仙.

/僊 (xiān, Old Chinese: /*sen/; "celestial being") had the complex phonetic component 䙴 (Old Chinese: /*sʰen/) simplified into 山 (Old Chinese: /*sreːn/), creating the clerical form 仙.

One consequence of the libian transition process is that many radicals formed as a result of simplifying complex components within seal script characters (for example, characters containing "heart" ![]() /心 on the side had the component simplified into 忄, as seen in 情 and 恨), and these newly-formed radicals are still used in modern-day Chinese writing as the fundamental basis for constructing and sorting Chinese characters.

/心 on the side had the component simplified into 忄, as seen in 情 and 恨), and these newly-formed radicals are still used in modern-day Chinese writing as the fundamental basis for constructing and sorting Chinese characters.

Examples

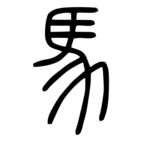

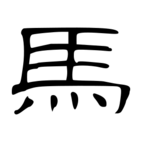

| English | Ancient form | Libian form | Pinyin | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| year, harvest | 秊 | 年 | nián | Originally |

| thunder | 靁 | 雷 | léi | Originally semantic 雨 ("rain") + phonetic 畾 (Old Chinese: /*ruːl/), the bottom component became reduced into 田 during libian.[5][6] |

| to make offerings to the dead | 奠 | diàn | Originally a pictogram of an alcohol vessel (酉) placed upon a mat (一), two strokes (八) were added to later forms to represent overflowing alcohol, and a further two strokes (八) were subsequently added to the mat to form a table with two legs (丌). During libian, the 丌 mutated into 大, resulting in the clerical form.[7][8] | |

| by, therefore, because, etc. | 㠯 | 以 | yǐ | Originally a pictogram of a person (人) carrying an object, the seal script form |

| to obtain | 𢔶 | 得 | dé | Seal script form |

| to include | 圅 | 函 | hán | Seal script form |

| to change | 㪅 | 更 | gèng | Seal script form |

| board game | 棊 | 棋 | qí | Seal script form |

| without | 橆 | 無 | wú | Ancient bronze form |

| thought | 恖 | 思 | sī | Seal script form |

| front, forward | 歬 | 前 | qián | Seal script form |

| side by side, simultaneously, furthermore | 竝 | 並 | bìng | Seal script form |

| hill | 丠 | 丘 | qiū | Seal script form |

| to ascend | 椉 | 乘 | chéng | Seal script form |

| to revolve around | 𠄢 | 亘 | xuān | Seal script form |

| fourth earthly branch | 戼 | 卯 | mǎo | Originally depicted a Shang dynasty ritual of splitting a sacrificial body in half, as seen in seal script form |

| death | 𣦸 | 死 | sǐ | Originally an ideogrammic compound consisting of |

| to leave, to rid | 㚎 | 去 | qù | Seal script form |

| also, emphatic final particle | 也 | yě | Shuowen Jiezi describes this character as a pictogram of a female vulva. Libian form is significantly simplified from the original shape.[38][39] | |

| summer, Xia dynasty | 夓 | 夏 | xià | The libian form removes the 𦥑 component and the legs of 頁 ("head") from the seal script form |

| what, exceed | 𠥄 | 甚 | shèn, shén | The libian form modulates the upper component of the seal script form |

| to live, to birth, raw | 𤯓 | 生 | shēng | Seal script form |

| to use | 𤰃 | 用 | yòng | Seal script form |

| alliance | 𥂗 | 盟 | méng | Seal script form |

| flower | 𠌶 | 花 | huā | Seal script form |

| Malva verticillata, Livistona chinensis, Basella alba | 𦮙 | 葵 | kuí | Seal script form 𦮙.[55][56] |

| west | 㢴 | 西 | xī | Seal script form |

| edge, border, side | 𨘢 | 邊 | biān | The earlier bronze inscription form |

| to eat | 𠊊 | 食 | shí | Seal script form |

| fantasy | 𠄔 | 幻 | huàn | Seal script form |

| hometown | 鄉 | xiāng | Originally an ideogrammic compound consisting of 𠨍 ("two people facing each other") + 皀 ("food vessel") within bronze inscriptions, representing "to feast". During the transition to the seal script form, 𠨍 became corrupted into 𨙨 and 邑 (23px). Following libian simplification, 邑 became simplified into the etymologically cognate 阝 radical, 𨙨 simplified into the unrelated 乡 radical (cognate to | |

| fragrant | 香 | xiāng | Seal script form consisted of 黍 ("proso millet") + 甘 ("sweet"); the libian form simplifies 黍 into 禾 ("cereal plant"), and replaces the bottom 甘 component with the unrelated character 曰 ("to say").[67][68] | |

| fish | 𤋳 | 魚 | yú | Seal script form |

| night | 𡖍 | 夜 | yè | Seal script form |

| stomach | 胃 | wèi | The pictographic component | |

| excrement | 𦳊 | 屎 | shǐ | Seal script form |

| to migrate | 徙 | xǐ | The 止 portion of the left 辵 component was relocated to the right during libian, resulting in two 止 on top of one another, coincidentally becoming unified with the same structure as 歨 ( |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 李綉玲. "從隸變看秦簡記號化現象" (in zh). Feng Chia University. http://www.fyu.url.tw/cp/27th/27th_P305.pdf.

- ↑ "Learning and Teaching of Chinese Characters" (in zh). https://www.edb.gov.hk/attachment/tc/curriculum-development/kla/chi-edu/resources/primary/lang/Learning%20and%20Teaching%20of%20Chinese%20Characters_Prof%20Sin.pdf.

- ↑ "年" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%B9%B4.

- ↑ "A01194" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01194.

- ↑ "雷" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E9%9B%B7.

- ↑ "A04472" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A04472.

- ↑ "奠" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%A5%A0.

- ↑ "A00872" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00872.

- ↑ "以" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E4%BB%A5.

- ↑ "A00078" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00078.

- ↑ "得" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%BE%97.

- ↑ "A01291" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01291.

- ↑ "函" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%87%BD.

- ↑ "A00327" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00327.

- ↑ "更" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E6%9B%B4.

- ↑ "A01833" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01833.

- ↑ "棋" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E6%A3%8B.

- ↑ "A01966" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01966.

- ↑ "無" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E7%84%A1.

- ↑ "A02416" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A02416.

- ↑ "思" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E6%80%9D.

- ↑ "A01330" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01330.

- ↑ "前" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%89%8D.

- ↑ "A00355" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00355.

- ↑ "並" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E4%B8%A6.

- ↑ "A00018" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00018.

- ↑ "丘" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E4%B8%98.

- ↑ "A00015" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00015.

- ↑ "乘" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E4%B9%98.

- ↑ "A00037" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00037.

- ↑ "N00001" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=N00001.

- ↑ "卯" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%8D%AF.

- ↑ "A00448" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00448.

- ↑ "死" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E6%AD%BB.

- ↑ "A02077" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A02077.

- ↑ "去" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%8E%BB.

- ↑ Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- ↑ "也" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E4%B9%9F.

- ↑ "A00040" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00040.

- ↑ "夏" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%A4%8F.

- ↑ "A00837" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00837.

- ↑ "甚" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E7%94%9A.

- ↑ "A02621" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A02621.

- ↑ "生" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E7%94%9F.

- ↑ "A02623" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A02623.

- ↑ "用" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E7%94%A8.

- ↑ "A02627" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A02627.

- ↑ "盟" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E7%9B%9F.

- ↑ "A02749" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A02749.

- ↑ "明" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E6%98%8E.

- ↑ "A01784" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01784.

- ↑ "花" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E8%8A%B1.

- ↑ "A03503-018" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A03503-018.

- ↑ "華" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E8%8F%AF.

- ↑ "葵" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E8%91%B5.

- ↑ "A03522" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A03522.

- ↑ "西" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E8%A5%BF.

- ↑ "A03762" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A03762.

- ↑ "邊" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E9%82%8A.

- ↑ "A04196" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A04196.

- ↑ "食" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E9%A3%9F.

- ↑ "A04581" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A04581.

- ↑ "幻" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%B9%BB.

- ↑ "A01197" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01197.

- ↑ "鄉" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E9%84%89.

- ↑ "A04217" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A04217.

- ↑ "香" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E9%A6%99.

- ↑ "A04616" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A04616.

- ↑ "魚" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E9%AD%9A.

- ↑ "A04691" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A04691.

- ↑ "夜" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%A4%9C.

- ↑ "A00843" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. https://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A00843.

- ↑ "胃" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E8%83%83.

- ↑ "A03311" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. http://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A03311.

- ↑ "屎" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%B1%8E.

- ↑ "A01086" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. http://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01086.

- ↑ "徙" (in zh). Chinese University of Hong Kong. https://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/lexi-mf/search.php?word=%E5%BE%99.

- ↑ "A01292" (in zh). National Academy for Educational Research. http://dict.variants.moe.edu.tw/variants/rbt/word_attribute.rbt?educode=A01292.

KSF

KSF