Linguistic areas of the Americas

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 23 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 23 min

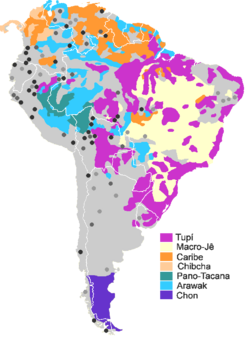

The indigenous languages of the Americas form various linguistic areas or Sprachbunds that share various common (areal) traits. The following list of linguistic areas is primarily based on Campbell (1997, 2024).

Overview

The languages of the Americas often can be grouped together into linguistic areas or Sprachbunds (also known as convergence areas). The linguistic areas identified so far deserve more research to determine their validity. Knowing about Sprachbunds helps historical linguists differentiate between shared areal traits and true genetic relationship. The pioneering work on American areal linguistics was a dissertation by Joel Sherzer, which was published as Sherzer (1976).

Lyle Campbell (1997) lists over 20 linguistic areas,[1] many of which are still hypothetical.

Note: Some linguistic areas may overlap with others.

| Linguistic Area (Sprachbund) | Included families, branches, and languages |

|---|---|

| Eskimo-Aleut, Haida, Eyak, Tlingit | |

| Eyak, Tlingit, Athabaskan, Tsimshian, Wakashan, Chimakuan, Salishan, Alsea, Coosan, Kalapuyan, Takelma, Lower Chinook | |

| Plateau[2] | Sahaptian, Upper Chinook, Nicola, Cayuse, Molala language, Klamath, Kutenai, Interior Salishan |

| Northern California | Algic, Athabaskan, Yukian, Miwokan, Wintuan, Maiduan, Klamath-Modoc, Pomo, Chimariko, Achomawi, Atsugewi, Karuk, Shasta, Yana, (Washo) |

| Clear Lake | Lake Miwok, Patwin, East and Southeastern Pomo, Wappo |

| South Coast Range | Chumash, Esselen, Salinan |

| Southern California–Western Arizona | Yuman, Cupan (Uto-Aztecan), less extensively Takic (Uto-Aztecan) |

| Great Basin[3] | Numic (Uto-Aztecan), Washo |

| Pueblo | Keresan, Tanoan, Zuni, Hopi, some Apachean branches |

| Plains | Athabaskan, Algonquian, Siouan, Tanoan, Uto-Aztecan, Tonkawa |

| Northeast | Winnebago (Siouan), Northern Iroquoian, Eastern Algonquian |

| Southeast ("Gulf") | Muskogean, Chitimacha, Atakapa, Tunica language, Natchez, Yuchi, Ofo (Siouan), Biloxi (Siouan) – sometimes also Tutelo, Catawban, Quapaw, Dhegiha (all Siouan); Tuscarora, Cherokee, Shawnee |

| Mesoamerican | Aztecan (Nahua branch of Uto-Aztecan), Mixe–Zoquean, Mayan, Xincan, Otomanguean (except Chichimeco–Jonaz and some Pame varieties, Totonacan), Purépecha, Cuitlatec, Tequistlatecan, Huave |

| Mayan[4] | Mayan, Xincan, Lencan, Jicaquean |

| Colombian–Central American[5] | Chibchan, Misumalpan, Mangue, Subtiaba; sometimes Lencan, Jicaquean, Chochoan, Betoi |

| Venezuelan–Antillean[6] | Arawakan, Cariban, Guamo, Otomaco, Yaruro, Warao |

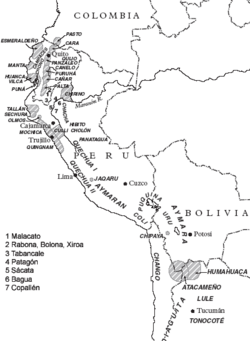

| Andean[7] | Quechuan, Aymaran, Callahuaya, Chipaya |

| Ecuadorian–Colombian (subarea of Andean) |

Páez, Guambiano (Paezan), Cuaiquer, Cayapa, Colorado (Barbacoan), Camsá, Cofán, Esmeralda, Ecuadorian Quechua |

| Orinoco–Amazon | Yanomaman, Piaroa (Sálivan), Arawakan/Maipurean, Cariban, Jotí, Uruak/Ahuaqué, Sapé (Kaliana), Máku |

| Amazon | Arawakan/Maipurean, Arauan/Arawan, Cariban, Chapacuran, Ge/Je, Panoan, Puinavean, Tacanan, Tucanoan, Tupian |

| Southern Cone | Mapudungun (Araucanian), Guaycuruan, Chon |

Lexical diffusion

Pache, et al. (2016)[8] note that the word ‘dog’[9] is shared across various unrelated language families of the Americas, and use this word as a case study of lexical diffusion due to trade and contact.

In California, identical roots for ‘dog’ are found in:[8][10]

- Yurok cʼišah, Karuk čišiːh, Takelma cʼíxi, Yokuts *cʼɨːsas

- Chimariko šičela, Wintu se-cilaː ‘to tear apart’

- Wintun *suku, Maiduan *sɨː, Washo súkuʔ, Miwok *hayu, Costanoan (Awaswas and Chocheño; Chocheño has the form čukuti). Pache, et al. (2016) posit a Wintun origin for this root.

- *hayu root in Miwok, Pomoan, Wappo, and Hill Patwin

- Ramaytush puku, Uto-Aztecan *punku

- Costanoan (Mutsun xučekniṣ, Chalon xučekniṣ, and Rumsen xučːiys), Esselen hučumas (term borrowed from Costanoan; native terms are šošo and šanašo), Salinan (Antoniaño Salinan xuč (pl. xostén) and Migueleño Salinan xučaːi), Chumash (Ineseño Chumash huču, likely borrowed from Salinan)

In South America, a root for ‘dog’ is shared by Uru-Chipayan (paku or paqu) and several unrelated neighboring languages of lowland Bolivia (Movima pako, Itonama u-paʔu, and Trinitario paku), as well as Guaicuruan (Mocoví, Toba, and Pilagá pioq). An identical root for ‘dog’ is also shared by Huastec (*sul) and Atakapa (šul), which are very geographically distant from each other although both are located along the Gulf of Mexico coast.[8] Areal words for ‘dog’ are also shared across the U.S. Southeast (Karankawa keš ~ kes, Chitimacha kiš, Cotoname kissa ‘fox’, Huavean *kisɨ), as well as across Mesoamerica. Mesoamerican areal words for ‘dog’ diffused unidirectionally from certain language families to others, and are listed below:[8]

- Proto-Mixe-Zoquean *ʔuku > Proto-Zapotec *kweʔkkoʔ (Ixtlán Zapotec beʔkoʔ) > Huastec pik’oʔ, Yucatec pè:k’

- P’urhépecha wiču > Chontal wičuʔ

- Totonacan čiči(ʔ) > Classical Nahuatl čiči

North America

Northern Northwest Coast

This linguistic area was proposed by Jeff Leer (1991), and may be a subarea of the Northwest Coast Linguistic Area. This sprachbund contains languages that have strict head-final (XSOV) syntax. Languages are Aleut, Haida, Eyak, and Tlingit.

Leer (1991) considers the strong areal traits to be:

- lack of labial obstruents

- promiscuous number marking

- periphrastic possessive construction

Northwest Coast

This linguistic area is characterized by elaborate consonant systems. Languages are Eyak, Tlingit, Athabaskan, Tsimshian, Wakashan, Chimakuan, Salishan, Alsea, Coosan, Kalapuyan, Takelma, and Lower Chinook. Phonological areal traits include:

- Series of glottalized stops and affricates

- Labiovelars

- Multiple laterals

- s/š opposition

- c/č opposition

- voiceless uvular stop q

- one fricative series, which is voiceless

- velar fricatives

- highly limited inventory of labial consonants

- large inventory of uvular consonants

- limited vowel systems

Typical shared morphological traits include:

- reduplication processes: including iterative, continuative, progressive, plural, collective

- numeral classifiers

- alienable/inalienable oppositions in nouns

- pronominal plural

- nominal plural

- verbal reduplication signifying distribution, repetition, etc.

- suffixation of tense-aspect markers in verbs

- verbal evidential markers

- locative-directional markers in the verb

- visibility/invisibility opposition in demonstratives

- nominal and verbal reduplication signaling the diminutive

- passive-like constructions (except for Tlingit)

- negative appearing as the first element in a clause regardless of the usual word order

- lexically paired singular and plural verb stems

Plateau

The Plateau linguistic area includes Sahaptian, Upper Chinook, Nicola, Cayuse, Molala language, Klamath, Kutenai, and Interior Salishan. Primary shared phonological features of this linguistic area include:

- glottalized stops

- velar/uvular contrasting series

- multiple laterals

Other less salient shared traits are:

- labiovelars

- one fricative series

- velar (and uvular) fricatives

- series of glottalized resonants (sonorants) contrasting with plain resonants (except in Sahaptin, Cayuse, Molala, and Kiksht)

- word-medial and word-final consonant clusters of four or more consonants (except in Kiksht, and uncertain in Cayuse and Molala)

- vowel systems of only 3 or 4 vowel positions (except Nez Perce, which has 5)

- vowel-length contrast

- size-shape-affective sound symbolism involving consonantal interchanges

- pronominal plural

- nominal plural

- prefixation of subject person markers of verbs

- suffixation of tense-aspect markers in verbs

- several kinds of reduplication (except in Nicola)

- numeral classifiers (shared by Salishan and Sahaptian languages)

- locative-directional markers in verbs

- different roots of the singular and the plural for various actions, such as 'sit', 'stand', 'take' (except in Kutenai and Lillooet, uncertain in Cayuse and Molala)

- quinary-decimal numerical system (Haruo Aoki 1975)

Northern California

The Northern California linguistic area consists of many Hokan languages. Languages include Algic, Athabaskan, Yukian, Miwokan, Wintuan, Maiduan, Klamath-Modoc, Pomo, Chimariko, Achomawi, Atsugewi, Karuk, Shasta, Yana, (Washo).

Features of this linguistic area have been described by Mary Haas. They include:

- rarity of uvular consonants: they occur in Klamath, Wintu, Chimariko, and Pomoan

- retroflexed stops

- rarity of a distinct series of voiced stops except in the east–west strip of languages including Kashaya Pomo, Wintu-Patwin, and Maidu (this series contains implosion in Maidu)

- consonant sound symbolism: in Yurok, Wiyot, Hupa, Tolowa, Karuk, and Yana

Washo, spoken in the Great Basin area, shares some traits common to the Northern California linguistic area.

- pronominal dual

- quinary/decimal numeral system

- absence of vowel-initial syllables

- free stress

Northwest California

Northwest California is a subarea of the Northern California linguistic area. It includes Wiyot (Algic), Yurok (Algic), Hupa (Athabaskan), and Karuk (language isolate).[11]

Central California

Golla (2011: 247–248) notes that Esselen shares typological features with Utian, Miwok, Costanoan, such as "the absence of a glottalized series, and ... a relatively analytic morphosyntax", which are also similar to typological features found in Northern Uto-Aztecan languages. He suggests that there was a linguistic area that stretched from the Sierra Nevada through Sacramento, and from the San Joaquin Delta to the San Francisco Bay.[12]

Shaul (2014: 203–207) also proposes typological connections between Esselen, Salinan, Chumashan, some Utian languages, and Uto-Aztecan.[13] Similarities between Utian and various neighboring language families have also been noted by Callaghan (2014).[14][11]

Clear Lake

Clear Lake is clearly a linguistic area, and is centered around Clear Lake, California. Languages are Lake Miwok, Patwin, East and Southeastern Pomo, and Wappo. Shared features include:

- retroflexed dentals

- voiceless l (ɬ)

- glottalized glides

- 3 series of stops

South Coast Range

Languages in Sherzer's (1976) "Yokuts-Salinan-Chumash" area (also known as the "South Coast Range" linguistic area[11]), which includes Chumash, Esselen, and Salinan, share the following traits.

- 3 series of stops - also in the Clear Lake area

- retroflexed sounds - also in the Clear Lake area

- glottalized resonants (sonorants)

- prefixation of verbal subject markers)

- presence of /h, ɨ, c, ŋ/ in the Greater South Coast Range area

- t/ṭ (retroflex/non-retroflex) contrast in the Greater South Coast Range area, as well as other parts of California

In an expanded version, the Greater South Coast Range linguistic area also includes Yokutsan and several Northern Uto-Aztecan languages.[11]

Great Basin

This linguistic area is defined by Sherzer (1973, 1976) and Jacobsen (1980). Languages are Numic (Uto-Aztecan) and Washo. Shared traits include:

- k/kʷ contrast

- bilabial fricatives /ɸ, β/

- presence of /xʷ, ŋ, ɨ/

- overtly marked nominal system

- inclusive/exclusive pronominal distinction

However, the validity of this linguistic area is doubtful, as pointed out by Jacobsen (1986), since many traits of the Great Basin area are also common to California languages. It may be an extension of the Northern California linguistic area.

Southern California–Western Arizona

This linguistic area has been demonstrated in Hinton (1991). Languages are Yuman, Cupan (Uto-Aztecan), and less extensively Takic (Uto-Aztecan). Shared traits include:

- k/q distinction

- presence of /kʷ, tʃ, x/

The Yuman and Cupan languages share the most areal features, such as:

- kʷ/qʷ contrast

- s/ʂ contrast

- r/l contrast

- presence of /xʷ, ɲ, lʲ/

- small vowel inventory

- sound symbolism

The influence is strongly unidirectional from Yuman to Cupan, since the features considered divergent within the Takic subgroup. According to Sherzer (1976), many of these traits are also common to Southern California languages.

Shaul and Andresen (1989) have proposed a Southwestern Arizona ("Hohokam") linguistic area as well, where speakers of Piman languages are hypothesized to have interacted with speakers of Yuman languages as part of the Hohokam archaeological culture. The single trait defining this area is the presence of retroflex stops (/ʈ/ in Yuman, /ɖ/ in Piman).

Pueblo

The Pueblo linguistic area consists of Keresan, Tanoan, Zuni, Hopi, and some Apachean branches.

Plains

The Plains Linguistic Area, according to Sherzer (1973:773), is the "most recently constituted of the culture areas of North America (late eighteenth and nineteenth century)." Languages are Athabaskan, Algonquian, Siouan, Tanoan, Uto-Aztecan, and Tonkawa. The following areal traits are characteristic of this linguistic area, though they are also common in other parts of North America.

- prefixation of subject person markers in verbs

- pronominal plurals

Frequent traits, which are not shared by all languages, include:

- one stop series

- the voiceless velar fricative /x/

- alienable/inalienable opposition in nouns

- nominal plural suffix

- inclusive/exclusive opposition (in first person plural pronouns)

- nominal diminutive suffix

- animate/inanimate gender

- evidential markers in verbs

- lack of labiovelars (other than Comanche and the languages of the Southern Plains subregion)

- presence of /ð/ (eastern Plains subregion only)

Southern Plains areal traits include:

- phonemic pitch

- presence of /kʷ, r/

- voiced/voiceless fricatives

Northeast

The Northeast linguistic area consists of Winnebago (Siouan), Northern Iroquoian, and Eastern Algonquian. Central areal traits of the Northeast Linguistic Area include the following (Sherzer 1976).

- a single series of stops (especially characteristic of the Northeast)

- a single series of fricatives

- presence of /h/

- nominal plural

- noun incorporation

In New England, areal traits include:

- vowel system with /i, e, o, a/

- nasalized vowels

- pronominal dual

New England Eastern Algonquian languages and Iroquoian languages share the following traits.

- nasalized vowels (best-known feature); for instance, Proto-Eastern Algonquian *a- is nasalized due to influence from Iroquioan languages, which have two nasalized vowels in its proto-language, *ɛ̃ and *õ.

- pronominal dual

The boundary between the Northeast and Southeast linguistic areas is not clearly determined, since features often extend over to territories belonging to both linguistic areas.

Southeast

Gulf languages include Muskogean, Chitimacha, Atakapa, Tunica language, Natchez, Yuchi, Ofo (Siouan), Biloxi (Siouan) –

sometimes also Tutelo, Catawban, Quapaw, Dhegiha (all Siouan); Tuscarora, Cherokee, and Shawnee.

Bilabial or labial fricatives (/ɸ/, sometimes /f/) are considered by Sherzer (1976) to be the most characteristic trait of the Southeast Linguistic Area. Various other shared traits have been found by Robert L. Rankin (1986, 1988) and T. Dale Nicklas (1994).

Mesoamerican

This linguistic area consists of the following language families and branches.

- Mayan

- Oto-Manguean (except Chichimeco-Jonaz and some varieties of Pame north of the Mesoamerican boundary)

- Mixe–Zoque

- Totonacan

- Aztecan (a Southern Uto-Aztecan branch)

- Purépecha

- Huave

- Tequistlatec

- Cuitlatec

Some languages formerly considered to be part of the Mesoamerican sprachbund, but are now considered to lack main diagnostic traits of Mesoamerican area languages, include Cora, Huichol, Lenca, Jicaquean, and Misumalpan.

Mayan

The Mayan Linguistic Area is considered by most scholars to be part of the Mesoamerican area. However, Holt & Bright (1976) distinguish it as a separate area, and include the Mayan, Xincan, Lencan, and Jicaquean families as part of the Mayan Linguistic Area. Shared traits include:

- presence of glottalized consonants and alveolar affricates

- absence of voiced obstruents and labiovelar stops

South America

Colombian–Central American

Colombian–Central American consists of Chibchan, Misumalpan, Mangue, and Subtiaba; sometimes Lencan, Jicaquean, Chocoan, and Betoi are also included.

This linguistic area is characterized by SOV word order and postpositions. This stands in contrast to the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area, where languages do not have SOV word order.

Holt & Bright (1976) define a Central American Linguistic Area as having the following areal traits. Note that these stand in direct opposition to the traits defined in their Mayan Linguistic Area.

- presence of voiced obstruents and labiovelar stops (absent in the Mayan area)

- absence of glottalized consonants and alveolar affricates (present in the Mayan area)

Constenla's (1991) Colombian–Central American area consists primarily of Chibchan languages, but also include Lencan, Jicaquean, Misumalpan, Chocoan, and Betoi (Constenla 1992:103). This area consists of the following areal traits.

- voicing opposition in stops and fricatives

- exclusive SOV word order

- postpositions

- mostly Genitive-Noun order

- Noun-Adjective order

- Noun-Numeral order

- clause-initial question words

- suffixation or postposed particle for negatives (in most languages)

- absence of gender opposition in pronouns and inflection

- absence of possessed/nonpossessed and alienable/inalienable possession oppositions

- "morpholexical economy" - presence of lexical compounds rather than independent roots. This is similar to calques found in Mesoamerica, but with a more limited number of compounding elements. For instance, in Guatuso (as in Athabaskan languages), there is one compounding element of liquid substances, one compounding element for pointed extremities, one for flat surfaces, and so on.

Venezuelan–Antillean

This linguistic area, consisting of Arawakan, Cariban, Guamo, Otomaco, Yaruro, and Warao, is characterized by VO word order (instead of SOV), and is described by Constenla (1991). Shared traits are:

- exclusive VO word order, and absence of SOV word order

- absence of voicing opposition in obstruents

- Numeral-Noun order

- Noun-Genitive order

- presence of prepositions

The Venezuelan–Antillean could also extend to the western part of the Amazon Culture Area (Amazonia), where there are many Arawakan languages with VO word order (Constenla 1991).

Andean

This linguistic area, consisting of Quechuan, Aymaran, Callahuaya, and Chipaya, is characterized by SOV word order and elaborate suffixing.

Quechuan and Aymaran languages both have:

- SOV basic word order

- suffixing morphology; other similar morphological structures

Büttner's (1983:179) includes Quechuan, Aymaran, Callahuaya, and Chipaya. Puquina, an extinct but significant language in this area, appears to not share these phonological features. Shared phonological traits are:

- glottalized stops and affricates (not found in all varieties of Quechuan)

- aspirated stops and affricates (not found in Chipaya)

- uvular stops

- presence of /ɲ, lʲ/

- retroflexed affricates (retroflexed /ʃ/ and /t͡ʃ/) - more limited in distribution

- absence of glottal stop /ʔ/

- limited vowel systems with /i, a, u/ (not in Chipaya)

Constenla (1991) defines a broader Andean area including the languages of highland Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and possibly also some lowland languages east of that Andes that have features typical of the Andean area. This area has the following areal traits.

- absence of the high-mid opposition in back vowels

- absence of the opposition of voiced/voiceless affricates

- presence of the voiceless alveolar affricate, voiceless prepalatal fricative, palatal lateral, palatal nasal, retroflexed fricatives or affricates

- Adjective-Noun order

- clause-initial interrogative words

- accusative case

- genitive case

- passive construction

Statistical studies

Quantitative studies on the Andes and overlapping areas have found the following traits to be characteristic of these areas in a statistically significant way.

Morphosyntactic features

A statistical study of argument marking features in languages of South America found that both the Andes and Western South America constitute linguistic areas, with some traits showing a statistically significant relationship to both areas. The unique and shared traits of the two areas are shown in the following table.[15] (The wordings of the traits are directly from the source.)

| Andes only | Both Andes and Western South America | Western South America only |

|---|---|---|

| Subject-object-verb constituent order | Use of both case and indexation as argument marking strategies | Marked neutral case marking patterns in ditransitive constructions |

| Suffixes as verbal person markers | Verbally marked applicative constructions | |

| The R argument role can be indexed in ditransitive constructions | ||

| Accusative case alignment for NP arguments |

Phonological features

Phonologically, the following segments and segmental features are areal for the Andes:[16]

Consonants

- A contrast between aspirated and ejective in the stops and the postalveolar affricate

- A "comparatively large number of affricates, fricatives, and liquids"

- The palatal place of articulation (in nasals and liquids)

- The uvular place of articulation (in stops and fricatives)

- The absence of the following types of consonants:

- Voiced alveolar stop and affricate

- Labialized velar voiceless stop and nasal

- Voiced bilabial and voiceless labiodental fricatives

- Glottal stop and fricative

Vowels

- The presence of short /u/ and long /iː, uː, aː/

- The absence of mid and non-low central vowels and nasal vowels, and "long versions of many of these vowels."

Amazon

The Amazon linguistic area includes the Arawakan/Maipurean, Arauan/Arawan, Cariban, Chapacuran, Ge/Je, Panoan, Puinavean, Tacanan, Tucanoan, and Tupian families.

Derbyshire & Pullum (1986) and Derbyshire (1987) describe the characteristics of this linguistic area in detail. Traits include:

- objects preceding subjects, such as VOS, OVS, and OSV; word order in OVS and OSV languages tends to be highly flexible

- verb agreement with both subject and object (additionally, null realization of subject and object nominals or free pronouns, which means that sentences frequently lack full noun-phrase subjects or objects)

- predictability of when subjects and objects will be full noun phrases or when they will be signalled by verbal affixes (depending on whether they represent "new" or "given" information)

- use of nominalizations for relative clauses and other subordinate clauses (in many cases, there are no true subordinate clauses at all)

- nominal modifiers following their head nouns

- no agentive passive constructions (except Palikur)

- indirect-speech forms are nonexistent in most languages and rare in the languages that do have them; thus, they rely on direct speech constructions

- absence of coordinating conjunctions (juxtaposition is used to express coordination instead)

- extensive use of right-dislocated paratactic constructions (sequences of noun phrases, adverbials, or postpositional phrases, in which the whole sequence has only one grammatical relation in the sentence)

- extensive use of particles that are phrasal subconstituents syntactically and phonologically, but are sentence operators or modifiers semantically

- tendency toward ergative subject marking

- highly complex morphology

Noun-classifier systems are also common across Amazonian languages. Derbyshire & Payne (1990) list three basic types of classifier systems.

- Numeral: lexico-syntactic forms, which are often obligatory in expressions of quantity and normally are separate words.

- Concordial: a closed grammatical system, consisting of morphological affixes or clitics and expressing class agreement with some head noun. However, they may also occur on nouns or verbs.

- Verb incorporation: lexical items are incorporated into the verb stem, signalling some classifying entity of the associated noun phrase.

Derbyshire (1987) also notes that Amazonian languages tend to have:

- ergatively organized systems (in whole or in part)

- evidence of historical drift from ergative to accusative marking

- certain types of split systems

Mason (1950) has found that in many languages of central and eastern Brazil, words end in vowels, and stress is ultimate (i.e., falls on the final syllable).

Lucy Seki (1999) has also proposed an Upper Xingu Linguistic Area in northern Brazil.

Validity

The validity of Amazonia as a linguistic area has been called into question by recent research, including quantitative studies. A study of argument marking parameters in 74 South American languages by Joshua Birchall found that “not a single feature showed an areal distribution for Amazonia as a macroregion. This suggests that Amazonia is not a good candidate for a linguistic area based on the features examined in this study.” Instead, Birchall finds evidence for three “macroregions” in South America: the Andes, Western South America, and Eastern South America, with some overlap in features between the Andes and Western South America.[17]

Based on that study and similar findings, Patience Epps and Lev Michael claim that “an emerging consensus points to Amazonia not forming a linguistic area sensu strictu [sic?].”[18]

Epps (2015)[19] shows that Wanderwörter are spread across the languages of Amazonia. Morphosyntax is also heavily borrowed across neighboring unrelated Amazonian languages.

Ecuadorian–Colombian

This is a subarea of the Andean Linguistic Area, as defined by Constenla (1991). Languages include Páez, Guambiano (Paezan), Cuaiquer, Cayapa, Colorado (Barbacoan), Camsá, Cofán, Esmeralda, and Ecuadorian Quechua. Shared traits are:

- high-mid opposition in front vowels

- absence of glottalized consonants

- presence of the glottal stop /ʔ/ and voiceless bilabial fricative /ɸ/

- absence of uvular stops /q, ɢ/

- rounding opposition in non-front vowels

- lack of person inflection in nouns

- prefixes expressing tense or aspect distinctions

Vaupés (Vaupés–Içana)

The Vaupés (Vaupés–Içana) linguistic area includes Eastern Tukanoan, Arawakan, Nadahup, and Kakua–Nukak language families, along with the local lingua franca Nheengatú. The linguistic area has been well studied by various linguists.[11]

Shared areal traits include:[11]

- nominal classification systems

- evidentiality

- serial verb constructions

- shared tense-aspect-mood values

- lexical calquing

Caquetá–Putumayo

The Caquetá–Putumayo linguistic area includes:[20]

Shared traits include:[11]

- first-person plural inclusive/exclusive contrast

- second-position tense-aspect-mood clitics

- loss of object cross-referencing suffixes

- verbal morphology restructuring

- borrowing of classifiers

- inhibition against lexical borrowing

- classifier systems

- /ɨ/ (high central unrounded vowel)

Orinoco–Amazon

The Orinoco–Amazon Linguistic Area, or the Northern Amazon Culture Area, is identified by Migliazza (1985 [1982]). Languages include Yanomaman, Piaroa (Sálivan), Arawakan/Maipurean, Cariban, Jotí, Uruak/Ahuaqué, Sapé (Kaliana), and Máku. Common areal traits are:

- a shared pattern of discourse redundancy (Derbyshire 1977)

- ergative alignment (except in a few Arawakan languages)

- objects preceding verbs, such as SOV and OVS word order (except in a few Arawakan languages)

- lack of active-passive distinction

- relative clauses formed by apposition and nominalization

The following traits have diffused from west to east (Migliazza 1985 [1982]):

- nasalization

- aspiration

- glottalization

Southern Guiana (Northeastern Amazonian)

The Southern Guiana (Northeastern Amazonian) linguistic area includes mostly Cariban languages, some Arawakan languages, Sálivan languages, Tupí-Guaranían languages, and Taruma. Yanomaman, Warao, Arutani, Sapé, and Maku (Mako) are sometimes also included.[11]

According to Carlin (2007), the Arawakan language Mawayana has borrowed many grammatical features from Cariban languages, particularly Tiriyó [Trió] and Waiwai. On the other hand, Wapishana, an Arawakan language that is closely related Mawayana, lacks these features.[21]

Shared grammatical features (also noted by Epps (2020),[22] Epps and Michael (2017: 948–949),[23] and Lüpke et al. (2020: 19–21)[24]) include:

- first-person plural exclusive distinction (borrowing from Waiwai)

- nominal tense marking

- marking on nouns or verbs to express ‘pity’ or ‘recognition of unfortunate circumstance’

- frustrative marker on verbs

- ‘similative’ marker on nominals

Tocantins–Mearim Interfluvium

The Tocantins–Mearim Interfluvium linguistic area includes several Tupí–Guaranían and Jêan languages.[11]

- Teneteháran branch: Guajajára, Tembé, and Turiwára

- Northern Tupí-Guaranían branch: Guajá and Urubú-Ka'apór

- Xingu branch: Anambé, Amanajé, and Ararandewára

- Tupí branch: Tupinambá and Língua Geral Amazônica

- Jêan: Timbira (3 dialects; see Braga et al. 2011: 224[25])

Shared grammatical traits include:[26]

- change in a grammatical particle

- change in gerund

- loss of first-person plural inclusive-exclusive contrast

- argumentative case

Upper Xingu

The Upper Xingu linguistic area includes more than a dozen languages belonging to the Cariban, Arawakan, Jêan, and Tupían families, as well as the language isolate Trumai.[11]

Lucy Seki (1999, 2011) Xingu is an "incipient" linguistic area, since many of the languages had arrived in the Upper Xingu area after the arrival of the Portuguese.[27][28] Shared linguistic traits include:[11]

- loss of a masculine-feminine gender distinction in the Arawakan languages of the region

- diffusion of /ɨ/ into Xingu Arawakan languages from their Cariban or Tupí-Guaranían neighbors (Chang and Michael 2014)[29]

- p > h shift in Cariban and Tupí-Guaranían

- change to CV syllable structure in Cariban

- diffusion of /ts/ into the Xingu Cariban languages from Arawakan

- diffusion of nasal vowels into the Xingu Arawakan and Cariban languages from neighboring Tupí-Guaranían languages

Influence is multidirectional, as noted by Epps and Michael (2017: 947).[23]

Mamoré–Guaporé

Crevels and van der Voort (2008) propose a Mamoré–Guaporé linguistic area in eastern lowland Bolivia (in Beni Department and Santa Cruz Department) and Rondonia, Brazil. In Bolivia, many of the languages were historically spoken at the Jesuit Missions of Moxos and also the Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos.

According to Campbell (2024), the Mamoré–Guaporé or Guaporé–Mamoré linguistic area includes over 50 languages from 17 different families (Arawakan, Chapacuran, Jabutían, Nambikwaran, Pano-Takanan, Tupían, 11 language isolates, 12 unclassified languages, and one pidgin).[11] Language families and branches in the linguistic area include Arawakan, Chapacuran, Jabuti, Rikbaktsá, Nambikwaran, Pano-Tacanan, and Tupian (Guarayo, Kawahib, Arikem, Tupari, Monde, and Ramarama) languages. Language isolates in the linguistic area are Cayuvava, Itonama, Movima, Chimane/Mosetén, Canichana, Yuracaré, Leco, Mure, Aikanã, Kanoê, and Kwazá, Irantxe, and Chiquitano. Areal features include:[30]

- a high incidence of prefixes

- evidentials

- directionals

- verbal number

- lack of nominal number

- lack of classifiers

- inclusive/exclusive distinction

Muysken et al. (2014) also performed a detailed statistical analysis of the Mamoré–Guaporé linguistic area.[31]

Chaco

According to Campbell (2024), the Gran Chaco linguistic area includes Charrúan, Enlhet-Enenlhet (Mascoyan), Guaicurúan, Guachí, Lule-Vilelan, Matacoan, Payaguá, Zamucoan, and some Tupí-Guaranían languages.[11]

Campbell and Grondona (2012) consider the Mataco–Guaicuru, Mascoyan, Lule-Vilelan, Zamucoan, and some southern Tupi-Guarani languages to be part of a Chaco linguistic area. Common Chaco areal features include SVO word order and active-stative alignment. Other shared traits, some of which are also found outside the Gran Chaco area, include:[32]

- gender that is not overtly marked on nouns, but is present in demonstratives, depending on the gender of the nouns modified

- genitive classifiers for possessed domestic animals

- SVO word order

- active-stative verb alignment

- large set of directional verbal affixes

- demonstrative system with rich contrasts including visible vs. not visible

- some adjectives as polar negatives

- resistance to borrowing foreign words

South Cone

The languages of the South Cone area, including Mapudungun (Araucanian), Guaycuruan, and Chon, share the following traits (Klein 1992):

- Semantic notions of position signaled morphologically by means of "many devices to situate the visual location of the noun subject or object relative to the speaker; tense, aspect and number are expressed as part of the morphology of location, direction, and motion" (Klein 1992:25).

- palatalization

- more back consonants than front consonants

- SVO basic word order

Fuegian

Adelaar and Muysken (2004: 578–582) note that the languages of the Tierra del Fuego, namely Chonan, Kawesqaran, Chono (isolate), and Yahgan (isolate), share areal traits relating to encliticization, suffixation, compounding, and reduplication, as well as object-initial (OV) word order.[33][11]

See also

- Classification of Indigenous languages of the Americas

Notes

- ↑ Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian languages: the historical linguistics of Native America. Ch. 9 Linguistic Areas of the Americas, pp. 330–352. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- ↑ Characterized by glottal stops

- ↑ May be a subarea of the Northern California Linguistic Area.

- ↑ Often included in the Mesoamerican sprachbund

- ↑ Characterized by SOV word order and postpositions

- ↑ Characterized by VO word order (instead of SOV)

- ↑ Characterized by SOV word order and elaborate suffixing

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Pache, Matthias, Søren Wichmann, and Mikhail Zhivlov. 2016. Words for ‘dog’ as a diagnostic of language contact in the Americas. In: Berez-Kroeker, Andrea L., Diane M. Hintz and Carmen Jany (eds.), Language Contact and Change in the Americas: Studies in Honor of Marianne Mithun, 385-409. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- ↑ Key, Mary Ritchie & Comrie, Bernard (eds.) 2015. The Intercontinental Dictionary Series. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Entry: dog.

- ↑ Note: Forms marked preceded by asterisks are proto-language reconstructions.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 Campbell, Lyle (2024). The Indigenous Languages of the Americas. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-767346-1.

- ↑ Golla, Victor. 2011. California Indian Languages. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Shaul, David L. 2014. A Prehistory of Western North America: The Impact of Uto-Aztecan Languages. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- ↑ Callaghan, Catherine A. 2014. Proto Utian Grammar and Dictionary, with Notes on Yokuts. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- ↑ Birchall (2014:215–16)

- ↑ Michael et al. (2012:14-15)

- ↑ Birchall (2014:225)

- ↑ Epps and Michael (to appear, 18-19)

- ↑ Epps, Patience. 2015. The dynamics of linguistic diversity: Language contact and language maintenance in Amazonia. Presented at Diversity Linguistics: Retrospect and Prospect, 1–3 May 2015 (Leipzig, Germany), Closing conference of the Department of Linguistics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Wojtylak, Katarzyna Izabela (2017). A Witotoan Language of Northwest Amazonia. PhD dissertation, James Cook University, Australia.

- ↑ Carlin, Eithne. 2007. Feeling the need: The borrowing of Cariban functional categories into Mawayana (Arawak). Grammars in Contact: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective, ed. by Alexandra Aikhenvald and Robert M. W. Dixon, 313–332. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Epps, Patience. 2020. Amazonian linguistic diversity and its sociocultural correlates. Language Dispersal, Diversification, and Contact: A Global Perspective, ed. by Mily Crevels and Pieter Muysken, 275–290. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Epps, Patience and Lev Michael. 2017. The areal linguistics of Amazonia. The Cambridge Handbook of Areal Linguistics, ed. by Raymond Hickey, 934–963. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Lüpke, Friederike, Kristine Stenzel, Flora Dias Cabalzar, Thiago Chacon, Aline da Cruz, Bruna Franchetto, Antonio Guerreiro, Sérgio Meira, Glauber Romling da Silva, Wilson Silva, and Luciana Storto. 2020. Comparing rural multilingualism in Lowland South America and Western Africa. Anthropological Linguistics 62.3–57.

- ↑ Braga, Alzerinda, Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara Cabral, Aryon DallʼIgna Rodrigues, and Betty Mindlin. 2011. Línguas entrelaçadas: uma situação sui generis de línguas em contato [Intertwined languages: a sui generis situation of languages contact]. PAPIA-Revista Brasileira de Estudos do Contato Linguístico [PAPIA-Brazilian Journal of Language Contact Studies] 21.221–230.

- ↑ Cabral, Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara, Ana B. Corrêa da Silva, Marina M. S. Magalhães, and Maria R. S. Julião. 2007. Linguistic diffusion in the Tocantins-Mearim area. Línguas e Culturas Tupí [Tupían Languages and Cultures] 1.357–374.

- ↑ Seki, Lucy. 1999. The Upper Xingu as an incipient linguistic area. The Amazonian Languages, ed. by Robert M. W. Dixon and Alexandra Aikhenvald, 417–430. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Seki, Lucy. 2011. Alto Xingu: Uma sociedade multilíngue? Alto Xingu: uma Sociedade Multilíngue, ed. by Bruna Franchetto, 57– 86. Rio de Janeiro: Museu do Indio/Funai.

- ↑ Chang, Will and Lev Michael. 2014. A relaxed admixture model of language contact. Language Dynamics and Change 4.1–26.

- ↑ Crevels, Mily; van der Voort, Hein (2008). "4. The Guaporé-Mamoré region as a linguistic area". From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics. Studies in Language Companion Series. 90. pp. 151–179. doi:10.1075/slcs.90.04cre. ISBN 978-90-272-3100-0.

- ↑ Muysken, Pieter; Hammarström, Harald; Birchall, Joshua; Van Gijn, Rik; Krasnoukhova, Olga; Müller, Neele (2014). Linguistic areas: bottom-up or top-down? The case of the Guaporé-Mamoré. In: Comrie, Bernard; Golluscio, Lucia. Language Contact and Documentation / Contacto lingüístico y documentación. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 205-238.

- ↑ Campbell, Lyle; Grondona, Verónica (2012). "Languages of the Chaco and Southern Cone". in Grondona, Verónica; Campbell, Lyle. The Indigenous Languages of South America. The World of Linguistics. 2. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 625–668. ISBN 9783110255133.

- ↑ Adelaar, Willem F. H. and Pieter C. Muysken. 2004. The Languages of the Andes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

References

- Birchall, Joshua. 2015. Argument marking patterns in South American languages. Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen: PhD Dissertation.

- Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian languages: the historical linguistics of Native America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, Lyle. 2024. The Indigenous Languages of the Americas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Epps, Patience and Lev Michael. To appear. "The areal linguistics of Amazonia."

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo. 1991. Las lenguas del área intermedia: introducción a su estudio areal. San José: Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica.

- Holt, Dennis and William Bright. 1976. "La lengua paya y las fronteras lingüística de Mesoamérica." Las fronteras de Mesoamérica. La 14a mesa redonda, Sociedad Mexicana de Antropología 1:149-156.

- Michael, Lev, Will Chang, and Tammy Stark. 2012. "Exploring phonological areality in the circum-Andean region using a Naive Bayes Classifier." Language Dynamics and Change 4(1): 27–86. (Page numbers in this article refer to the pages of the linked PDF, not the journal version.)

- Sherzer, Joel. 1973. "Areal linguistics in North America." In Linguistics in North America, ed. Thomas A. Sebeok, 749–795. (CTL, vol. 10.) The Hague: Mouton.

- Sherzer, Joel. 1976. An areal-typological study of American Indian languages north of Mexico. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

External links

- Languages of hunter-gatherers and their neighbors: A collection of lexical, grammatical, and other information about languages spoken by hunter-gatherers and their neighbors.

- South American Indigenous Language Structures (SAILS)

|

KSF

KSF