Oʼodham language

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

| Oʼodham | |

|---|---|

| Oʼodham ha-ñeʼokĭ, Oʼottham ha-neoki, Oʼodham ñiok | |

| Pronunciation | ood |

| Native to | United States, Mexico |

| Region | Primarily south-central Arizona and northern Sonora |

| Ethnicity | Tohono Oʼodham, Akimel Oʼodham, Hia C-eḍ Oʼodham |

Native speakers | 15,000 (2007)[1] 180 monolinguals (1990 census); 1,240 (Mexico, 2020 census)[2] |

Uto-Aztecan

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | One of the national languages of Mexico[3] |

| Regulated by | Secretariat of Public Education in Mexico; various tribal agencies in the United States |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ood |

| Glottolog | toho1245[4] |

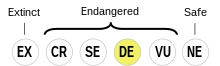

Oʼodham is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[5] | |

Oʼodham: (ood, English approximation: /ˈoʊ.ɒðəm, -dəm/ OH-od(h)-əm) or Papago-Pima is a Uto-Aztecan language of southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico, where the Tohono Oʼodham (formerly called the Papago) and Akimel Oʼodham (traditionally called Pima) reside.[6] In 2000 there were estimated to be approximately 9,750 speakers in the United States and Mexico combined, although there may be more due to underreporting.

It is the 10th most-spoken indigenous language in the United States, and the 3rd most-spoken indigenous language in Arizona (after Western Apache and Navajo). It is the third-most spoken language in Pinal County, Arizona, and the fourth-most spoken language in Pima County, Arizona.

Approximately 8% of Oʼodham speakers in the US speak English "not well" or "not at all", according to results of the 2000 Census. Approximately 13% of Oʼodham speakers in the US were between the ages of 5 and 17, and among the younger Oʼodham speakers, approximately 4% were reported as speaking English "not well" or "not at all".

Native names for the language, depending on the dialect and orthography, include Oʼodham ha-ñeʼokĭ, Oʼottham ha-neoki, and Oʼodham ñiok.

Dialects

The Oʼodham language has a number of dialects.[7]

- Oʼodham

- Tohono Oʼodham

- Cukuḍ Kuk

- Gigimai

- Huhuʼula (Huhuwoṣ)

- Totoguanh

- Akimel Oʼodham

- Eastern Gila

- Kohadk

- Salt River

- Western Gila

- Hia C-ed Oʼodham

- ?

- Tohono Oʼodham

Due to the paucity of data on the linguistic varieties of the Hia C-eḍ Oʼodham, this section currently focuses on the Tohono Oʼodham and Akimel Oʼodham dialects only.

The greatest lexical and grammatical dialectal differences are between the Tohono Oʼodham (or Papago) and the Akimel Oʼodham (or Pima) dialect groupings. Some examples:

| Tohono Oʼodham | Akimel Oʼodham | English |

|---|---|---|

| ʼaʼad | hotṣ | to send |

| nhenhida | tamiam | to wait for |

| s-hewhogĭ | s-heubagĭ | to be cool |

| sisiṣ | hoʼiumi (but si꞉ṣpakuḍ, stapler) | to fasten |

| pi꞉ haʼicug | pi ʼac | to be absent |

| wia | ʼoʼoid | hunt tr. |

There are other major dialectal differences between northern and southern dialects, for example:

| Early Oʼodham | Southern | Northern | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| *ʼa꞉phi꞉m | ʼa꞉ham | ʼa꞉pim | you (plural) |

| *cu꞉khug | cu꞉hug | cu꞉kug | flesh |

| *ʼe꞉kheg | ʼe꞉heg | ʼe꞉keg | to be shaded |

| *ʼu꞉pham | ʼu꞉hum | ʼu꞉pam | (go) back |

The Cukuḍ Kuk dialect has null in certain positions where other Tohono Oʼodham dialects have a bilabial:

| Other TO dialects | Chukuḍ Kuk | English |

|---|---|---|

| jiwia, jiwa | jiia | to arrive |

| ʼuʼuwhig | ʼuʼuhig | bird |

| wabṣ | haṣ | only |

| wabṣaba, ṣaba | haṣaba | but |

Morphology

Oʼodham is an agglutinative language, where words use suffix complexes for a variety of purposes with several morphemes strung together.

Phonology

Oʼodham phonology has a typical Uto-Aztecan inventory distinguishing 19 consonants and 5 vowels.[8]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | ʔ | |

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | d͡ʒ | g | ||

| Fricative | ð s | ʂ | h | ||||

| Approximant | w | j | |||||

| Flap | ɭ | ||||||

The retroflex consonants are apical postalveolar.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i iː | ɨ ɨː | ʊ uː |

| Mid | ə | ɔ ɔː | |

| Low | a aː |

Most vowels distinguish two degrees of length: long and short, and some vowels also show extra-short duration (voicelessness).

- ṣe꞉l /ʂɨːɭ/ "Seri"

- ṣel /ʂɨɭ/ "permission"

- ʼa꞉pi /ʔaːpi/ "you"

- da꞉pĭ /daːpɪ̥/ "I don't know", "who knows?"

Papago /ɨ/ is pronounced [ʌ] in Pima.

Additionally, in common with many northern Uto-Aztecan languages, vowels and nasals at end of words are devoiced. Also, a short schwa sound, either voiced or unvoiced depending on position, is often interpolated between consonants and at the ends of words.

Allophony and distribution

- Extra short ⟨ĭ⟩ is realized as voiceless [i̥] and devoices preceding obstruents: cuwĭ /tʃʊwi̥/ → [tʃʊʍi̥]~[tʃʊʍʲ] "jackrabbit".

- /w/ is a fricative [β] before unrounded vowels: wisilo [βisiɭɔ].

- [ŋ] appears before /k/ and /ɡ/ in Spanish loanwords, but native words do not have nasal assimilation: to꞉nk [toːnk] "hill", namk [namk] "meet", ca꞉ŋgo [tʃaːŋɡo] "monkey". /p/, /ɭ/, and /ɖ/ rarely occur initially in native words, and /ɖ/ does not occur before /i/.

- [ɲ] and [n] are largely in complementary distribution, [ɲ] appearing before high vowels /i/ /ɨ/ /ʊ/, [n] appearing before low vowels /a/ /ɔ/: ñeʼe "sing". They contrast finally (ʼañ (1st imperfective auxiliary) vs. an "next to speaker"), though Saxton analyzes these as /ani/ and /an/, respectively, and final [ɲi] as in ʼa꞉ñi as /niː/. However, there are several Spanish loanwords where [nu] occurs: nu꞉milo "number". Similarly, for the most part [t] and [d] appear before low vowels while [tʃ] and [dʒ] before high vowels, but there are exceptions to both, often in Spanish loanwords: tiki꞉la ("tequila") "wine", TO weco / AO veco ("[de]bajo") "under".

Orthography

There are two orthographies commonly used for the Oʼodham language: Alvarez–Hale and Saxton. The Alvarez–Hale orthography is officially used by the Tohono Oʼodham Nation and the Salt River Pima–Maricopa Indian Community, and is used in this article, but the Saxton orthography is also common and is official in the Gila River Indian Community. It is relatively easy to convert between the two, the differences between them being largely no more than different graphemes for the same phoneme, but there are distinctions made by Alvarez–Hale not made by Saxton.

| Phoneme | Alvarez–Hale | Saxton | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | a ʼaʼal | a aʼal | baby |

| /b/ | b ban | b ban | coyote |

| /tʃ/ | c cehia | ch chehia | girl |

| /ð/ | d daak | th thahk | nose |

| /ɖ/ | ḍ meḍ | d med | run |

| /d/ | ḏ juḏum | d judum | bear |

| TO /ɨ/, AO /ʌ/ | e ʼeʼeb | e eʼeb | stop crying |

| /ɡ/ | g gogs | g gogs | dog |

| /h/ | h haʼicu | h haʼichu | something |

| TO /i/, AO /ɨ/ | i ʼiibhai | i ihbhai | prickly pear cactus |

| /dʒ/ | j juukĭ | j juhki | rain |

| /k/ | k keek | k kehk | stand |

| /ɭ/ | l luulsi | l luhlsi | candy |

| /m/ | m muunh | m muhni | bean(s) |

| /n/ | n naak | n nahk | ear |

| /ɲ/ | nh nheʼe, mu꞉nh | n, ni neʼe, muhni | sing, bean(s) |

| /ŋ/ | ng anghil, wa꞉nggo | ng, n anghil, wahngo | angel, bank |

| /ɔ/ | o ʼoʼohan | o oʼohan | write |

| /p/ | p pi | p pi | not |

| /s/ | s sitol | s sitol | syrup |

| /ʂ/ | ṣ ṣoiga | sh shoiga | pet |

| /t/ | t toobĭ | t tohbi | cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii) |

| /u/ | u ʼuus | u uhs | tree, wood |

| /v/ | v vainom | v vainom | knife |

| /w/ | w wuai | w wuai | male deer |

| /j/ | y payaso | y pa-yaso | clown |

| /ʔ/ | ʼ ʼaʼan | ʼ aʼan | feather |

| /ː/ | doubled vowel juukĭ (see colon (letter)) | h juhki | rain |

The Saxton orthography does not mark word-initial /ʔ/ or extra-short vowels. Final ⟨i⟩ generally corresponds to Hale–Alvarez ⟨ĭ⟩ and final ⟨ih⟩ to Hale–Alvarez ⟨i⟩:

- Hale–Alvarez toobĭ vs. Saxton tohbi /toːbĭ/ "cottontail rabbit"

- Hale–Alvarez ʼaapi vs. Saxton ahpih /ʔaːpi/ "I"

Disputed spellings

There is some disagreement among speakers as to whether the spelling of words should be only phonetic or whether etymological principles should be considered as well.

For instance, oamajda vs. wuamajda ("frybread"; the spellings oamacda and wuamacda are also seen) derives from oam (a warm color roughly equivalent to yellow or brown). Some believe it should be spelled phonetically as wuamajda, reflecting the fact that it begins with /ʊa/, while others think its spelling should reflect the fact that it is derived from oam (oam is itself a form of s-oam, so while it could be spelled wuam, it is not since it is just a different declension of the same word).

Grammar

Syntax

Oʼodham has relatively free word order within clauses; for example, all of the following sentences mean "the boy brands the pig":[9]

- ceoj ʼo g ko꞉jĭ ceposid

- ko꞉jĭ ʼo g ceoj ceposid

- ceoj ʼo ceposid g ko꞉jĭ

- ko꞉jĭ ʼo ceposid g ceoj

- ceposid ʼo g ceoj g ko꞉jĭ

- ceposid ʼo g ko꞉jĭ g ceoj

In principle, these could also mean "the pig brands the boy", but such an interpretation would require an unusual context.

Despite the general freedom of sentence word order, Oʼodham is fairly strictly verb-second in its placement of the auxiliary verb (in the above sentences, it is ʼo):

- cipkan ʼañ "I am working"

- but pi ʼañ cipkan "I am not working", not **pi cipkan ʼañ

Verbs

Verbs are inflected for aspect (imperfective cipkan, perfective cipk), tense (future imperfective cipkanad), and number (plural cicpkan). Number agreement displays absolutive behavior: verbs agree with the number of the subject in intransitive sentences, but with that of the object in transitive sentences:

- ceoj ʼo cipkan "the boy is working"

- cecoj ʼo cicpkan "the boys are working"

- ceoj ʼo g ko꞉ji ceposid "the boy is branding the pig"

- cecoj ʼo g ko꞉ji ceposid "the boys are branding the pig"

- ceoj ʼo g kokji ha-cecposid "the boy is branding the pigs"

The main verb agrees with the object for person (ha- in the above example), but the auxiliary agrees with the subject: ʼa꞉ñi ʼañ g kokji ha-cecposid "I am branding the pigs".

Nouns

Three numbers are distinguished in nouns: singular, plural, and distributive, though not all nouns have distinct forms for each. Most distinct plurals are formed by reduplication and often vowel loss plus other occasional morphophonemic changes, and distributives are formed from these by gemination of the reduplicated consonant:[10]

- gogs "dog", gogogs "dogs", goggogs "dogs (all over)"

- ma꞉gina "car", mamgina "cars", mammagina "cars (all over)"

- mi꞉stol "cat", mimstol "cats"

Adjectives

Oʼodham adjectives can act both attributively modifying nouns and predicatively as verbs, with no change in form.

- ʼi꞉da ṣu꞉dagĭ ʼo s-he꞉pid "This water is cold"

- ʼs-he꞉pid ṣu꞉dagĭ ʼañ hohoʼid "I like cold water"

Sample text

The following is an excerpt from Oʼodham Piipaash Language Program: Taḏai ("Roadrunner").[11] It exemplifies the Salt River dialect.

- Na꞉nse ʼe꞉da, mo꞉ hek jeweḍ ʼu꞉d si we꞉coc, ma꞉ṣ hek Taḏai siskeg ʼu꞉d ʼuʼuhig. Hek ʼaʼanac c wopo꞉c si wo skegac c ʼep si cecwac. Kuṣ ʼam hebai hai ki g ʼOʼodham ṣam ʼoʼoidam k ʼam ʼupam da꞉da k ʼam ce꞉ ma꞉ṣ he꞉kai cu hek ha na꞉da. ʼI꞉dam ʼOʼodham ṣam ʼeh he꞉mapa k ʼam aʼaga ma꞉ṣ has ma꞉sma vo bei hek na꞉da ʼab ʼamjeḍ hek Tatañki Jioṣ. Ṣa biʼi ʼa ma꞉ṣ mo ka꞉ke hek Taḏai ma꞉ṣ mo me꞉tk ʼamo ta꞉i hek na꞉da ha we꞉hejeḍ ʼi꞉dam ʼOʼodham. Taḏai ṣa꞉ ma so꞉hi ma꞉ṣ mo me꞉ḍk ʼamo ta꞉i g na꞉da hek Tatañki Jioṣ. Tho ṣud me꞉tkam, ʼam "si ʼi nai꞉ṣ hek wo꞉gk" k gau mel ma꞉ṣ ʼam ki g Tatañki Jioṣ.

In Saxton orthography:

- Nahnse ehtha, moh hek jeved uhth sih vehchoch, mahsh hek Tadai siskeg uhth uʼuhig. Hek aʼanach ch vopohch sih vo skegach ch ep sih chechvach. Kush am hebai hai kih g Oʼottham sham oʼoitham k am upam thahtha k am cheh mahsh hehkai chu hek ha nahtha. Ihtham Oʼothham sham eh hehmapa k am aʼaga mahsh has mahsma vo bei hek nahtha ab amjeth hek Tatanigi Jiosh. Sha biʼih a mahsh mo kahke hek Tadai mahsh mo mehtk amo tahʼih hek nahtha ha vehhejed ihtham Oʼottham. Tadai shah ma sohhih mahsh mo mehdk amo tahʼih g nahtha hek Tatanigi Jiosh. Tho shuth mehtkam, am "sih ih naihsh hek vohgk" k gau mel mahsh am kih g Tatanigi Jiosh.

The following is a song from Oʼodham Hohoʼok Aʼagida (Oʼodham Legends and Lore) by Susanne Ignacio Enos, and Dean and Lucille Saxton.[12] It exemplifies the "Storyteller dialect".

In Saxton orthography:

- Ali s-kohmangi chemamangi wiapoʼogeʼeli, hemu aichu mahch k e ahnga. Wahsh ng uwi chechenga ch muʼikko ia melopa, oi wa pi e nako. Wahshana memenada ch gahghai chum a neinahim.

English:

- Little gray horned toad youth, he just now learned something and is telling about himself. Over there he visits a girl repeatedly. And comes many times, yet he can't make it. Over there he keeps running, trying to look across at her.

See also

- Tohono Oʼodham

- Pima Bajo language

References

- ↑ Oʼodham at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ "Hablantes de lengua indígena" (in es). INEGI. http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/poblacion/lindigena.aspx.

- ↑ "Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas" (in es). Ley General of 13 March 2003. Congreso de la Unión. http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Documentos/Federal/html/wo108985.html.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Tohono Oʼodham". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/toho1245.

- ↑ Moseley, Christopher; Nicolas, Alexandre. "Atlas of the world's languages in danger". https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026.

- ↑ Estrada Fernández, Zarina; Oseguera Montiel, Andrés (2015). "La documentación de la tradición oral entre los pima: el diablo pelea con la luna" (in es). Indiana (Berlin: Ibero-American Institute) 32: 125–152. doi:10.18441/ind.v32i0.125-152. ISSN 2365-2225. "El pima bajo es una lengua yutoazteca (yutonahua) de la rama tepimana. Otras tres lenguas de esta rama son el tepehuano del norte, el tepehuano del sur o sureste y el antiguo pápago, actualmente denominado oʼotam en Sonora y tohono oʼodham y akimel oʼodham (pima) en Arizona.".

- ↑ Saxton, Dean; Saxton, Lucille; Enos, Susie (1983). Tohono Oʼodham/Pima to English, English to Tohono Oʼodham/Pima Dictionary. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816519422.

- ↑ Saxton, Dean (January 1963). "Papago Phonemes". International Journal of American Linguistics (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press) 29 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1086/464708. ISSN 1545-7001.

- ↑ Zepeda, Ofelia (2016). A Tohono Oʼodham Grammar. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816507924.

- ↑ Callahan, Rick (2016). A comprehensive introduction to grammar in linguistics. University Publications. ISBN 978-1-283-49963-7.

- ↑ Oʼodham Piipaash Language Program. Taḏai. Salt River, AZ: Oʼodham Piipaash Language Program

- ↑ Ignacio Enos, Susanne; Saxton, Dean; Saxton, Lucille (1969). Oʼodham Hohoʼok Aʼagida. p. 236. https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/70969.

External links

| Oʼodham language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Oʼodham Swadesh vocabulary list (Wiktionary)

- Papago – English Dictionary

- – Includes stories with phonetic transcription, audio, and translation created by linguist Madeleine Mathiot with Jose Pancho and others.

- Oʼodham Hohoʼok Aʼagida – Oʼodham legends with side-by-side English translations by Susanne Ignacio Enos and Dean and Lucille Saxton.

|

KSF

KSF