Reflective practice

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on one's actions so as to engage in a process of continuous learning.[1] According to one definition it involves "paying critical attention to the practical values and theories which inform everyday actions, by examining practice reflectively and reflexively. This leads to developmental insight".[2] A key rationale for reflective practice is that experience alone does not necessarily lead to learning; deliberate reflection on experience is essential.[3][4]

Reflective practice can be an important tool in practice-based professional learning settings where people learn from their own professional experiences, rather than from formal learning or knowledge transfer. It may be the most important source of personal professional development and improvement. It is also an important way to bring together theory and practice; through reflection a person is able to see and label forms of thought and theory within the context of his or her work.[5] A person who reflects throughout his or her practice is not just looking back on past actions and events, but is taking a conscious look at emotions, experiences, actions, and responses, and using that information to add to his or her existing knowledge base and reach a higher level of understanding.[6]

History and background

Donald Schön's 1983 book The Reflective Practitioner introduced concepts such as reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action which explain how professionals meet the challenges of their work with a kind of improvisation that is improved through practice.[1] However, the concepts underlying reflective practice are much older. Earlier in the 20th century, John Dewey was among the first to write about reflective practice with his exploration of experience, interaction and reflection.[7] Soon thereafter, other researchers such as Kurt Lewin and Jean Piaget were developing relevant theories of human learning and development.[8] Some scholars have claimed to find precursors of reflective practice in ancient texts such as Buddhist teachings[9] and the Meditations of Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius.[10]

Central to the development of reflective theory was interest in the integration of theory and practice, the cyclic pattern of experience and the conscious application of lessons learned from experience. Since the 1970s, there has been a growing literature and focus around experiential learning and the development and application of reflective practice.

As adult education professor David Boud and his colleagues explained: "Reflection is an important human activity in which people recapture their experience, think about it, mull it over and evaluate it. It is this working with experience that is important in learning."[11] When a person is experiencing something, he or she may be implicitly learning; however, it can be difficult to put emotions, events, and thoughts into a coherent sequence of events. When a person rethinks or retells events, it is possible to categorize events, emotions, ideas, etc., and to compare the intended purpose of a past action with the results of the action. Stepping back from the action permits critical reflection on a sequence of events.[6]

The emergence in more recent years of blogging has been seen as another form of reflection on experience in a technological age.[12]

Models

Many models of reflective practice have been created to guide reasoning about action.

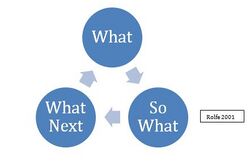

Borton 1970

Terry Borton's 1970 book Reach, Touch, and Teach popularized a simple learning cycle inspired by Gestalt therapy composed of three questions which ask the practitioner: What, So what, and Now what?[13] Through this analysis, a description of a situation is given which then leads into the scrutiny of the situation and the construction of knowledge that has been learnt through the experience. Subsequently, practitioners reflect on ways in which they can personally improve and the consequences of their response to the experience. Borton's model was later adapted by practitioners outside the field of education, such as the field of nursing and the helping professions.[14]

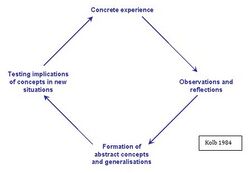

Kolb and Fry 1975

Learning theorist David A. Kolb was highly influenced by the earlier research conducted by John Dewey and Jean Piaget.[citation needed] Kolb's reflective model, which also draws from the works of Kurt Lewin,[15] highlights the concept of experiential learning and is centered on the transformation of information into knowledge.[16] This takes place after a situation has occurred, and entails a practitioner reflecting on the experience, gaining a general understanding of the concepts encountered during the experience, and then testing these general understandings in a new situation.[15] In this way, the knowledge that is formed from a situation is continuously applied and reapplied, building on a practitioner's prior experiences and knowledge.[17]

Argyris and Schön 1978

Management researchers Chris Argyris and Donald Schön introduced the "theory of action", which emerged out of their previous research on relationship between people and organizations.[18] This theory defines learning as detection and correction of error.[18][19] It included the distinction between single-loop learning and double-loop learning in 1978. Single-loop learning is when a practitioner or organisation, even after an error has occurred and a correction is made, continues to rely on current strategies, techniques or policies when a situation again comes to light. Double-loop learning involves the modification of objectives, strategies or policies so that when a similar situation arises a new framing system is employed.[20][page needed]

Schön claimed to derive the notions of "reflection-on-action, reflection-in-action, responding to problematic situations, problem framing, problem solving, and the priority of practical knowledge over abstract theory" from the writings of John Dewey, although education professor Harvey Shapiro has argued that Dewey's writings offer "more expansive, more integrated notions of professional growth" than do Schön's.[21]

Schön advocated two types of reflective practice. Firstly, reflection-on-action, which involves reflecting on an experience that you have already had, or an action that you have already taken, and considering what could have been done differently, as well as looking at the positives from that interaction. The other type of reflection Schön notes is reflection-in-action, or reflecting on your actions as you are doing them, and considering issues like best practice throughout the process.

For Schön, professional growth really begins when a person starts to view things with a critical lens, by doubting his or her actions. Doubt brings about a way of thinking that questions and frames situations as "problems". Through careful planning and systematic elimination of other possible problems, doubt is settled, and people are able to affirm their knowledge of the situation. Then people are able to think about possible situations and their outcomes, and deliberate about whether they carried out the right actions.[citation needed]

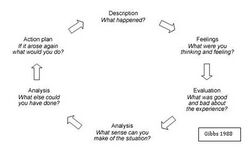

Gibbs 1988

Learning researcher Graham Gibbs discussed the use of structured debriefing to facilitate the reflection involved in Kolb's experiential learning cycle. Gibbs presents the stages of a full structured debriefing as follows:[22]

- (Initial experience)

- Description

- "What happened? Don't make judgements yet or try to draw conclusions; simply describe."

- Feelings

- "What were your reactions and feelings? Again don't move on to analysing these yet."

- Evaluation

- "What was good or bad about the experience? Make value judgements."

- Analysis

- "What sense can you make of the situation? Bring in ideas from outside the experience to help you."

- "What was really going on?"

- "Were different people's experiences similar or different in important ways?"

- Conclusions (general)

- "What can be concluded, in a general sense, from these experiences and the analyses you have undertaken?"

- Conclusions (specific)

- "What can be concluded about your own specific, unique, personal situation or way of working?"

- Personal action plans

- "What are you going to do differently in this type of situation next time?"

- "What steps are you going to take on the basis of what you have learnt?"

Gibbs' suggestions are often cited as "Gibbs' reflective cycle" or "Gibbs' model of reflection", and simplified into the following six distinct stages to assist in structuring reflection on learning experiences:[23]

- Description

- Feelings

- Evaluation

- Analysis

- Conclusions

- Action plan

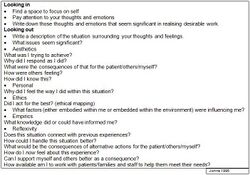

Johns 1995

Professor of nursing Christopher Johns designed a structured mode of reflection that provides a practitioner with a guide to gain greater understanding of his or her practice.[24] It is designed to be carried out through the act of sharing with a colleague or mentor, which enables the experience to become learnt knowledge at a faster rate than reflection alone.[25]

Johns highlights the importance of experienced knowledge and the ability of a practitioner to access, understand and put into practice information that has been acquired through empirical means. Reflection occurs though "looking in" on one's thoughts and emotions and "looking out" at the situation experienced. Johns draws on the work of Barbara Carper to expand on the notion of "looking out" at a situation.[26] Five patterns of knowing are incorporated into the guided reflection: the aesthetic, personal, ethical, empirical and reflexive aspects of the situation. Johns' model is comprehensive and allows for reflection that touches on many important elements.[27]

Brookfield 1998

Adult education scholar Stephen Brookfield proposed that critically reflective practitioners constantly research their assumptions by seeing practice through four complementary lenses: the lens of their autobiography as learners of reflective practice, the lens of other learners' eyes, the lens of colleagues' experiences, and the lens of theoretical, philosophical and research literature.[28] Reviewing practice through these lenses makes us more aware of the power dynamics that infuse all practice settings. It also helps us detect hegemonic assumptions—assumptions that we think are in our own best interests, but actually work against us in the long run.[28] Brookfield argued that these four lenses will reflect back to us starkly different pictures of who we are and what we do.

- Lens 1: Our autobiography as a learner. Our autobiography is an important source of insight into practice. As we talk to each other about critical events in our practice, we start to realize that individual crises are usually collectively experienced dilemmas. Analyzing our autobiographies allows us to draw insight and meanings for practice on a deep visceral emotional level.

- Lens 2: Our learners' eyes. Seeing ourselves through learners' eyes, we may discover that learners are interpreting our actions in the way that we mean them. But often we are surprised by the diversity of meanings people read into our words and actions. A cardinal principle of seeing ourselves through learners' eyes is that of ensuring the anonymity of their critical opinions. We have to make learners feel safe. Seeing our practice through learners' eyes helps us teach more responsively.

- Lens 3: Our colleagues' experiences. Our colleagues serve as critical mirrors reflecting back to us images of our actions. Talking to colleagues about problems and gaining their perspective increases our chance of finding some information that can help our situation.

- Lens 4: Theoretical literature. Theory can help us "name" our practice by illuminating the general elements of what we think are idiosyncratic experiences.

Application

Reflective practice has been described as an unstructured or semi-structured approach directing learning, and a self-regulated process commonly used in health and teaching professions, though applicable to all professions.[1][11][29] Reflective practice is a learning process taught to professionals from a variety of disciplines, with the aim of enhancing abilities to communicate and making informed and balanced decisions. Professional associations such as the American Association of Nurse Practitioners are recognizing the importance of reflective practice and require practitioners to prepare reflective portfolios as a requirement to be licensed, and for yearly quality assurance purposes.[citation needed]

Education

The concept of reflective practice has found wide application in the field of education, for learners, teachers and those who teach teachers (teacher educators). Tsangaridou & O'Sullivan (1997) define reflection in education as "the act of thinking about, analyzing, assessing, or altering educational meanings, intentions, beliefs, decisions, actions, or products by focusing on the process of achieving them … The primary purpose of this action is to structure, adjust, generate, refine, restructure, or alter knowledge and actions that inform practice. Microreflection gives meaning to or informs day-to-day practice, and macroreflection gives meaning to or informs practice over time".[30] Reflection is the key to successful learning for teachers and for learners.

Students

Students can benefit from engaging in reflective practice as it can foster the critical thinking and decision making necessary for continuous learning and improvement.[31] When students are engaged in reflection, they are thinking about how their work meets established criteria; they analyze the effectiveness of their efforts, and plan for improvement.[31] Rolheiser and et al. (2000) assert that "Reflection is linked to elements that are fundamental to meaningful learning and cognitive development: the development of metacognition – the capacity for students to improve their ability to think about their thinking; the ability to self-evaluate - the capacity for students to judge the quality of their work based on evidence and explicit criteria for the purpose of doing better work; the development of critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making; and the enhancement of teacher understanding of the learner." (p 31-32)

When teachers teach metacognitive skills, it promotes student self-monitoring and self-regulation that can lead to intellectual growth, increase academic achievement, and support transfer of skills so that students are able to use any strategy at any time and for any purpose.[32] Guiding students in the habits of reflection requires teachers to approach their role as that of "facilitator of meaning-making" – they organize instruction and classroom practice so that students are the producers, not just the consumers, of knowledge.[33] Rolheiser and colleagues (2000) state that "When students develop their capacity to understand their own thinking processes, they are better equipped to employ the necessary cognitive skills to complete a task or achieve a goal. Students who have acquired metacognitive skills are better able to compensate for both low ability and insufficient information." (p. 34)

The Ontario Ministry of Education (2007)[34] describes many ways in which educators can help students acquire the skills required for effective reflection and self-assessment, including: modelling and/or intentionally teaching critical thinking skills necessary for reflection and self-assessment practices; addressing students' perceptions of self-assessment; engaging in discussion and dialogue about why self-assessment is important; allowing time to learn self-assessment and reflection skills; providing many opportunities to practice different aspects of the self-assessment and reflection process; and ensuring that parents/guardians understand that self-assessment is only one of a variety of assessment strategies that is utilized for student learning.

Teachers

The concept of reflective practice is now widely employed in the field of teacher education and teacher professional development and many programs of initial teacher education claim to espouse it.[3] Education professor Hope Hartman has described reflective practice in education as teacher metacognition.,[35] indicating there is broad consensus that teaching effectively requires a reflective approach.[36][37][38] Attard & Armour explain that "teachers who are reflective systematically collect evidence from their practice, allowing them to rethink and potentially open themselves to new interpretations".[39] Teaching and learning are complex processes, and there is not one right approach. Reflecting on different approaches to teaching, and reshaping the understanding of past and current experiences, can lead to improvement in teaching practices.[40] Schön's reflection-in-action can help teachers explicitly incorporate into their decision-making the professional knowledge that they gain from their experience in the classroom.[41]

As professor of education Barbara Larrivee argues, reflective practice moves teachers from their knowledge base of distinct skills to a stage in their careers where they are able to modify their skills to suit specific contexts and situations, and eventually to invent new strategies.[29] In implementing a process of reflective practice teachers will be able to move themselves, and their schools, beyond existing theories in practice.[40] Larrivee concludes that teachers should "resist establishing a classroom culture of control and become a reflective practitioner, continuously engaging in a critical reflection, consequently remaining fluid in the dynamic environment of the classroom".[29] It is important to note that, "the reflective process should eventually help the teacher to change, adapt and modify his/her teaching to the particular context. This does not happen in stages, but is a continuum of reflection, leading to change ... and further reflection".[39]

Without reflection, teachers are not able to look objectively at their actions or take into account the emotions, experience, or consequences of actions to improve their practice. It is argued that, through the process of reflection, teachers are held accountable to the standards of practice for teaching, such as those in Ontario: commitment to students and student learning, professional knowledge, professional practice, leadership in learning communities, and ongoing professional learning.[42] Overall, through reflective practice, teachers look back on their practice and reflect on how they have supported students by treating them "equitably and with respect and are sensitive to factors that influence individual student learning".[42]

Teacher educators

For students to acquire necessary skills in reflection, their teachers need to be able to teach and model reflective practice (see above); similarly, teachers themselves need to have been taught reflective practice during their initial teacher education, and to continue to develop their reflective skills throughout their career.

However, Mary Ryan has noted that students are often asked to "reflect" without being taught how to do so,[43] or without being taught that different types of reflection are possible; they may not even receive a clear definition or rationale for reflective practice.[44] Many new teachers do not know how to transfer the reflection strategies they learned in college to their classroom teaching.[38]

Some writers have advocated that reflective practice needs to be taught explicitly to student teachers because it is not an intuitive act;[45][43] it is not enough for teacher educators to provide student teachers with "opportunities" to reflect: they must explicitly "teach reflection and types of reflection" and "need explicitly to facilitate the process of reflection and make transparent the metacognitive process it entails".[46] Larrivee noted that (student) teachers require "carefully constructed guidance" and "multifaceted and strategically constructed interventions" if they are to reflect effectively on their practice.[29]

Rod Lane and colleagues listed strategies by which teacher educators can promote a habit of reflective practice in pre-service teacher education, such as discussions of a teaching situation, reflective interviews or essays about one's teaching experiences, action research, or journaling or blogging.[47]

Neville Hatton and David Smith, in a brief literature review, concluded that teacher education programs do use a wide range of strategies with the aim of encouraging students teachers to reflect (e.g. action research, case studies, video-recording or supervised practicum experiences), but that "there is little research evidence to show that this [aim] is actually being achieved".[48]

The implication of all this is that teacher educators must also be highly skilled in reflective practice. Andrea Gelfuso and Danielle Dennis, in a report on a formative experiment with student teachers, suggested that teaching how to reflect requires teacher educators to possess and deploy specific competences.[49] However, Janet Dyment and Timothy O'Connell, in a small-scale study of experienced teacher educators, noted that the teacher educators they studied had received no training in using reflection themselves, and that they in turn did not give such training to their students; all parties were expected to know how to reflect.[50]

Many writers advocate for teacher educators themselves to act as models of reflective practice.[51][52] This implies that the way that teacher educators teach their students needs to be congruent with the approaches they expect their students to adopt with pupils; teacher educators should not only model the way to teach, but should also explain why they have chosen a particular approach whilst doing so, by reference to theory; this implies that teacher educators need to be aware of their own tacit theories of teaching and able to connect them overtly to public theory.[53] However, some teacher educators do not always "teach as they preach";[54] they base their teaching decisions on "common sense" more than on public theory[55] and struggle with modelling reflective practice.[51]

Tom Russell, in a reflective article looking back on 35 years as teacher educator, concurred that teacher educators rarely model reflective practice, fail to link reflection clearly and directly to professional learning, and rarely explain what they mean by reflection, with the result that student teachers may complete their initial teacher education with "a muddled and negative view of what reflection is and how it might contribute to their professional learning".[52] For Russell, these problems result from the fact that teacher educators have not sufficiently explored how theories of reflective practice relate to their own teaching, and so have not made the necessary "paradigmatic changes" which they expect their students to make.[52]

Challenges

Reflective practice "is a term that carries diverse meaning"[42] and about which there is not complete consensus. Professor Tim Fletcher of Brock University argues forward-thinking is a professional habit, but we must reflect on the past to inform how it translates into the present and future. Always thinking about 'what's next' rather than 'what just happened' can constrain an educator's reflective process. The concept of reflection is difficult as beginning teachers are stuck between "the conflicting values of schools and universities" and "the contradictory values at work within schools and within university faculties and with the increasing influence of factors external to school and universities such as policy makers".[56] Conflicting opinions make it difficult to direct the reflection process, as it is hard to establish what values you are trying to align with. It is important to acknowledge reflective practice "follows a twisting path that involves false starts and detours".[56] Meaning once you reflect on an issue it cannot be set aside as many assume. Newman refers to Gilroy's assertion that "the 'knowledge' produced by reflection can only be recognized by further reflection, which in turn requires reflection to recognize it as knowledge". In turn, reflective practice cannot hold one meaning, it is contextual based on the practitioner. It is argued that the term 'reflection' shouldn't be used as there are associations to it being "more of a hindrance than a help". It is suggested the term is referred to 'critical practice' or 'practical philosophy' to "suggest an approach which practitioners can adopt in the different social context in which they find themselves".[57] Finally, Oluwatoyin discusses some disadvantages and barriers to reflective practice as, feeling stress by reflecting on negative issues and frustration from not being able to solve those identified issues, and time constraints. Finally, with reflection often taking place independently, educators lack the motivation and assistance in tackling these difficult problems. It is suggested that teachers communicate with one another, or have an indicated individual to talk to, this way there is external informed feedback.[58] Overall, before engaging in reflective practice it is important to be aware of the challenges.

Health professionals

Reflective practice is viewed as an important strategy for health professionals who embrace lifelong learning. Due to the ever-changing context of healthcare and the continual growth of medical knowledge, there is a high level of demand on healthcare professionals' expertise. Due to this complex and continually changing environment, healthcare professionals could benefit from a program of reflective practice.[59]

Adrienne Price explained that there are several reasons why a healthcare practitioner would engage in reflective practice: to further understand one's motives, perceptions, attitudes, values, and feelings associated with client care; to provide a fresh outlook to practice situations and to challenge existing thoughts, feelings, and actions; and to explore how the practice situation may be approached differently.[60] In the field of nursing there is concern that actions may run the risk of habitualisation, thus dehumanizing patients and their needs.[61] In using reflective practice, nurses are able to plan their actions and consciously monitor the action to ensure it is beneficial to their patient.[61]

The act of reflection is seen as a way of promoting the development of autonomous, qualified and self-directed professionals, as well as a way of developing more effective healthcare teams.[62] Engaging in reflective practice is associated with improved quality of care, stimulating personal and professional growth and closing the gap between theory and practice.[63][page needed] Medical practitioners can combine reflective practice with checklists (when appropriate) to reduce diagnostic error.[64]

Activities to promote reflection are now being incorporated into undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing medical education across a variety of health professions.[65] Professor of medical education Karen Mann and her colleagues found through a 2009 literature review that in practicing professionals the process of reflection appears to include a number of different aspects, and practicing professionals vary in their tendency and ability to reflect. They noted that the evidence to support curricular interventions and innovations promoting reflective practice remains largely theoretical.[65]

Samantha Davies identified benefits as well as limitations to reflective practice:[66]

Benefits to reflective practice include:

- Increased learning from an experience or situation

- Promotion of deep learning

- Identification of personal and professional strengths and areas for improvement

- Identification of educational needs

- Acquisition of new knowledge and skills

- Further understanding of own beliefs, attitudes and values

- Encouragement of self-motivation and self-directed learning

- Could act as a source of feedback

- Possible improvements of personal and clinical confidence

Limitations to reflective practice include:

- Not all practitioners may understand the reflective process

- May feel uncomfortable challenging and evaluating own practice

- Could be time-consuming

- May have confusion as to which situations/experiences to reflect upon

- May not be adequate to resolve clinical problems[60]

Environmental management and sustainability

The use of reflective practice in environmental management, combined with system monitoring, is often called adaptive management.[67] There is some criticism that traditional environmental management, which simply focuses on the problem at hand, fails to integrate into the decision making the wider systems within which an environment is situated.[68] While research and science must inform the process of environmental management, it is up to the practitioner to integrate those results within these wider systems.[69] In order to deal with this and to reaffirm the utility of environmental management, Bryant and Wilson propose that a "more reflective approach is required that seeks to rethink the basic premises of environmental management as a process".[68] This style of approach has been found to be successful in sustainable development projects where participants appreciated and enjoyed the educational aspect of utilizing reflective practice throughout. However, the authors noted the challenges with melding the "circularity" of reflective practice theory with the "doing" of sustainability.[70]

Leadership positions

Reflective practice provides a development opportunity for those in leadership positions. Managing a team of people requires a delicate balance between people skills and technical expertise, and success in this type of role does not come easily. Reflective practice provides leaders with an opportunity to critically review what has been successful in the past and where improvement can be made.

Reflective learning organizations have invested in coaching programs for their emerging and established leaders.[71] Leaders frequently engage in self-limiting behaviours because of their over-reliance on their preferred ways of reacting and responding.[72] Coaching can help support the establishment of new behaviours, as it encourages reflection, critical thinking and transformative learning. Adults have acquired a body of experience throughout their life, as well as habits of mind that define their world.[73] Coaching programs support the process of questioning and potentially rebuilding these pre-determined habits of mind. The goal is for leaders to maximize their professional potential, and in order to do this, there must be a process of critical reflection on current assumptions.[74]

Other professions

Reflective practice can help any individual to develop personally, and is useful for professions other than those discussed above. It allows professionals to continually update their skills and knowledge and consider new ways to interact with their colleagues. David Somerville and June Keeling suggested eight simple ways that professionals can practice more reflectively:[75]

- Seek feedback: Ask "Can you give me some feedback on what I did?"

- Ask yourself "What have I learnt today?" and ask others "What have you learnt today?"

- Value personal strengths: Identify positive accomplishments and areas for growth

- View experiences objectively: Imagine the situation is on stage and you are in the audience

- Empathize: Say out loud what you imagine the other person is experiencing

- Keep a journal: Record your thoughts, feelings and future plans; look for emerging patterns

- Plan for the future: Plan changes in behavior based on the patterns you identified

- Create your own future: Combine the virtues of the dreamer, the realist, and the critic

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Schön, Donald A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465068746. OCLC 8709452.

- ↑ Bolton, Gillie (2010). Reflective practice: writing and professional development (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications. p. xix. ISBN 9781848602113. OCLC 458734364.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Loughran, J. John (January 2002). "Effective reflective practice: in search of meaning in learning about teaching". Journal of Teacher Education 53 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1177/0022487102053001004. http://oneteacher.global2.vic.edu.au/files/2014/09/Loughlan-242761j.pdf.

- ↑ Cochran-Smith, Marilyn; Lytle, Susan L. (January 1999). "Relationships of knowledge and practice: teacher learning in communities". Review of Research in Education 24 (1): 249–305. doi:10.3102/0091732X024001249.

- ↑ McBrien, Barry (July 2007). "Learning from practice—reflections on a critical incident". Accident and Emergency Nursing 15 (3): 128–133. doi:10.1016/j.aaen.2007.03.004. PMID 17540574.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Paterson, Colin; Chapman, Judith (August 2013). "Enhancing skills of critical reflection to evidence learning in professional practice". Physical Therapy in Sport 14 (3): 133–138. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2013.03.004. PMID 23643448. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236637498.

- ↑ Dewey, John (1998). How we think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0395897546. OCLC 38878663.

- ↑ Kolb, Alice Y.; Kolb, David A. (2005). "Learning styles and learning spaces: enhancing experiential learning in higher education". Academy of Management Learning and Education 4 (2): 193–212. doi:10.5465/AMLE.2005.17268566.

- ↑ Winter, Richard (March 2003). "Buddhism and action research: towards an appropriate model of inquiry for the caring professions". Educational Action Research 11 (1): 141–160. doi:10.1080/09650790300200208.

- ↑ Suibhne, Seamus Mac (September 2009). "'Wrestle to be the man philosophy wished to make you': Marcus Aurelius, reflective practitioner". Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 10 (4): 429–436. doi:10.1080/14623940903138266.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Boud, David; Keogh, Rosemary; Walker, David (1985). Reflection, turning experience into learning. London; New York: Kogan Page; Nichols. p. 19. ISBN 978-0893972028. OCLC 11030218.

- ↑ Wopereis, Iwan G.J.H.; Sloep, Peter B.; Poortman, Sybilla H. (2010). "Weblogs as instruments for reflection on action in teacher education". Interactive Learning Environments 18 (3): 245–261. doi:10.1080/10494820.2010.500530. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220095297.

- ↑ Borton, Terry (1970). Reach, touch, and teach: student concerns and process education. New York: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 178000. https://archive.org/details/reachtouchteachs00bort.

- ↑ Rolfe, Gary; Freshwater, Dawn; Jasper, Melanie (2001). Critical reflection for nursing and the helping professions: a user's guide. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave. pp. 26–35. ISBN 978-0333777954. OCLC 46984997.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Scaife, Joyce (2010). Supervising the Reflective Practitioner: An Essential Guide to Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-415-47957-8.

- ↑ Utley, Rose; Henry, Kristina; Smith, Lucretia (2017) (in en). Frameworks for Advanced Nursing Practice and Research: Philosophies, Theories, Models, and Taxonomies. New York: Springer Publishing Company. pp. 103. ISBN 978-0-8261-3322-9.

- ↑ Kolb, David A.; Fry, Ronald E. (1975). "Towards an applied theory of experiential learning". in Cooper, Cary L.. Theories of group processes. Wiley series on individuals, groups, and organizations. London; New York: Wiley. pp. 33–58. ISBN 978-0471171171. OCLC 1103318.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Easterby-Smith, Mark; Araujo, Luis; Burgoyne, John (1999). Organizational Learning and the Learning Organization: Developments in Theory and Practice. London: SAGE. pp. 160. ISBN 0-7619-5915-7.

- ↑ Smith, Mark K. (2013). "Chris Argyris: theories of action, double-loop learning and organizational learning". The encyclopedia of informal education. http://www.infed.org/thinkers/argyris.htm.

- ↑ Argyris, Chris; Schön, Donald A. (1996). Organizational learning: a theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley OD series. 1. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0201001747. OCLC 503599388. https://archive.org/details/organizationalle00chri.

- ↑ Shapiro, Harvey (2010). "John Dewey's reception in 'Schönian' reflective practice". Philosophy of Education Archive: 311–319 [311]. http://ojs.ed.uiuc.edu/index.php/pes/article/view/3049.

- ↑ Gibbs, Graham (1988). Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. London: Further Education Unit. ISBN 978-1853380716. OCLC 19809667. http://www2.glos.ac.uk/gdn/gibbs/. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Finlay, Linda (January 2008). Reflecting on 'reflective practice' (PDF) (Technical report). Practice-based Professional Learning Centre, The Open University. p. 8. PBPL paper 52.

- ↑ Johns, Christopher; Burnie, Sally (2013). Becoming a reflective practitioner (4th ed.). Chichester, UK; Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470674260. OCLC 823139850. https://books.google.com/books?id=LWifyeS9ol0C.

- ↑ Johns, Christopher, ed (2010). Guided reflection: a narrative approach to advancing professional practice (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK; Ames, Iowa: Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781444324969. ISBN 9781405185684. OCLC 502392750. https://books.google.com/books?id=Uf-3GyLX1QwC.

- ↑ Carper, Barbara A. (October 1978). "Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing". Advances in Nursing Science 1 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1097/00012272-197810000-00004. PMID 110216.

- ↑ Johns, Christopher (August 1995). "Framing learning through reflection within Carper's fundamental ways of knowing in nursing". Journal of Advanced Nursing 22 (2): 226–234. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22020226.x. PMID 7593941.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Brookfield, Stephen D. (Autumn 1998). "Critically reflective practice". Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 18 (4): 197–205. doi:10.1002/chp.1340180402. http://library.sau.edu/committee/brookfieldCritically.pdf.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Larrivee, Barbara (2000). "Transforming teaching practice: becoming the critically reflective teacher". Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 1 (3): 293–307. doi:10.1080/713693162. http://ed253jcu.pbworks.com/f/Larrivee_B_2000CriticallyReflectiveTeacher.pdf.

- ↑ Tsangaridou, N., & O'Sullivan, M. (1997). "The role of reflection in shaping physical education teachers' educational values and practices". Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 17 (1): 2–25. doi:10.1123/jtpe.17.1.2.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Rolheiser, C. Bower, B. Stevahn, L (2000). The Portfolio Organizer: Succeeding with Portfolios in your Classroom. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development..

- ↑ Ontario Ministry of Education (2008). "Connecting Practice and Research: Metacognition Guide". Queens Printer. http://www.edugains.ca/resourcesCurrImpl/Secondary/FSL/SupplementaryMaterials/ConnectingPracticeandResearchMetacognitionGuide.pdf.

- ↑ Costa, A., Kallick, B. (2008). Learning and leading with habits of mind: 16 essential characteristics for success.. Alexandria, VA: Association for supervision and Curriculum Development.

- ↑ Ontario Ministry of Education (2007). "Capacity Building Series: Student Self Assessment". Queens Printer. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/studentselfassessment.pdf.

- ↑ Hartman, Hope J. (2001). "Teaching metacognitively". in Hartman, Hope J.. Metacognition in learning and instruction: theory, research, and practice. Neuropsychology and cognition. 19. Dordrecht; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 149–172. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-2243-8_8. ISBN 978-0792368380. OCLC 45655382.

- ↑ Hatton, Neville; Smith, David (January 1995). "Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation". Teaching and Teacher Education 11 (1): 33–49. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U.

- ↑ Cochran-Smith, Marilyn (January 2003). "Learning and unlearning: the education of teacher educators". Teaching and Teacher Education 19 (1): 5–28. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00091-4.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Jones, Jennifer L.; Jones, Karrie A. (January 2013). "Teaching reflective practice: implementation in the teacher-education setting". The Teacher Educator 48 (1): 73–85. doi:10.1080/08878730.2012.740153.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Attard, K. & Armour, K. M. (2005). "Learning to become a learning professional: Reflections on one year of teaching". European Journal of Teacher Education 28 (2): 195–207. doi:10.1080/02619760500093321.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Leitch, Ruth; Day, Christopher (March 2000). "Action research and reflective practice: towards a holistic view". Educational Action Research 8 (1): 179–193. doi:10.1080/09650790000200108.

- ↑ Fien, John; Rawling, Richard (April 1996). "Reflective practice: a case study of professional development for environmental education". The Journal of Environmental Education 27 (3): 11–20. doi:10.1080/00958964.1996.9941462.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 "Standards of practice". Ontario College of Teachers. http://www.oct.ca/public/professional-standards/standards-of-practice.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Ryan, Mary (February 2013). "The pedagogical balancing act: teaching reflection in higher education". Teaching in Higher Education 18 (2): 144–155. doi:10.1080/13562517.2012.694104. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/54644/2/54644.pdf.

- ↑ Hébert, Cristyne (May 2015). "Knowing and/or experiencing: a critical examination of the reflective models of John Dewey and Donald Schön". Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 16 (3): 361–371. doi:10.1080/14623943.2015.1023281.

- ↑ Williams, Ruth; Grudnoff, Lexie (June 2011). "Making sense of reflection: a comparison of beginning and experienced teachers' perceptions of reflection for practice". Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 12 (3): 281–291. doi:10.1080/14623943.2011.571861.

- ↑ Nagle, James F. (December 2008). "Becoming a reflective practitioner in the age of accountability". The Educational Forum 73 (1): 76–86. doi:10.1080/00131720802539697.

- ↑ Lane, Rod; McMaster, Heather; Adnum, Judy; Cavanagh, Michael (July 2014). "Quality reflective practice in teacher education: a journey towards shared understanding". Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 15 (4): 481–494 [482]. doi:10.1080/14623943.2014.900022.

- ↑ Hatton, Neville; Smith, David (January 1995). "Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation". Teaching and Teacher Education 11 (1): 33–49 [36]. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U.

- ↑ Gelfuso A., Dennis D. (2014). "Getting reflection off the page: the challenges of developing support structures for pre-service teacher reflection". Teaching and Teacher Education 38: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.10.012.

- ↑ Dyment J.E., O'Connell T.S. (2014). "When the Ink Runs Dry: Implications for Theory and Practice When Educators Stop Keeping Reflective Journals". Innovation in HE 39 (5): 417–429. doi:10.1007/s10755-014-9291-6.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Loughran J., Berry A. (2005). "Modelling by teacher educators". Teaching and Teacher Education 21 (2): 193–203. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.005.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Russell T (2013). "Has Reflective Practice Done More Harm than Good in Teacher Education?". Phronesis 2 (1): 80–88. doi:10.7202/1015641ar.

- ↑ Swennen A., Lunenberg M., Korthagen F. (2008). "Preach what you teach! Teacher educators and congruent teaching". Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 14 (5): 531–542. doi:10.1080/13540600802571387.

- ↑ Lunenberg M., Korthagen F.A.J. (2003). "Teacher educators and student-directed learning". Teaching and Teacher Education 19: 29–44. doi:10.1016/s0742-051x(02)00092-6.

- ↑ Lunenberg M., Korthagen F., Swennen A. (2007). "The teacher educator as a role model". Teaching and Teacher Education 23 (5): 586–601. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.001.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Smagorinsky, P., Shelton, S. A., & Moore, C. (2015). "The role of reflection in developing eupraxis in learning to teach English". Pedagogies 10 (4): 285–308. doi:10.1080/1554480X.2015.1067146.

- ↑ Newman, S. (1999). "Constructing and critiquing reflective practice". Educational Action Research 7 (1): 145–163. doi:10.1080/09650799900200081.

- ↑ Tarrant, Peter (2013). Reflective practice and professional development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. pp. 42–46. doi:10.4135/9781526402318. ISBN 9781446249505. OCLC 811731533.

- ↑ Hendricks, Joyce; Mooney, Deborah; Berry, Catherine (April 1996). "A practical strategy approach to use of reflective practice in critical care nursing". Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 12 (2): 97–101. doi:10.1016/S0964-3397(96)81042-1. PMID 8845631.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Price, Adrienne (August 2004). "Encouraging reflection and critical thinking in practice". Nursing Standard 18 (47): 46–52. doi:10.7748/ns2004.08.18.47.46.c3664. PMID 15357553. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/eedc95c5477b5bd0069ea5e658a1fb1f63a22c06.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Walker, Susan (January 1996). "Reflective practice in the accident and emergency setting". Accident and Emergency Nursing 4 (1): 27–30. doi:10.1016/S0965-2302(96)90034-X. PMID 8696852.

- ↑ Ghaye, Tony (2005). Developing the reflective healthcare team. Oxford; Malden, MA: Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9780470774694. ISBN 978-1405105910. OCLC 58478682.

- ↑ Jasper, Melanie (2013). Beginning reflective practice. Nursing and health care practice series (2nd ed.). Andover: Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781408075265. OCLC 823552537.

- ↑ Graber, Mark L.; Kissam, Stephanie; Payne, Velma L.; Meyer, Ashley N. D.; Sorensen, Asta; Lenfestey, Nancy; Tant, Elizabeth; Henriksen, Kerm et al. (July 2012). "Cognitive interventions to reduce diagnostic error: a narrative review". BMJ Quality & Safety 21 (7): 535–557. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000149. PMID 22543420. http://www.ajustnhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/cog-interventions-diag-error-graber-BMJ-QS-2012.pdf.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Mann, Karen; Gordon, Jill; MacLeod, Anna (November 2007). "Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review". Advances in Health Sciences Education 14 (4): 595–621. doi:10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2. PMID 18034364. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5813985.

- ↑ Davies, Samantha (January 2012). "Embracing reflective practice". Education for Primary Care 23 (1): 9–12. doi:10.1080/14739879.2012.11494064. PMID 22306139.

- ↑ Salafsky, Nick Redford; Margoluis, Richard; Redford, Kent Hubbard (2001). Adaptive management: a tool for conservation practitioners. Washington, DC: Biodiversity Support Program. OCLC 48381963. http://www.fosonline.org/resource/am-tool.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Bryant, Raymond L.; Wilson, Geo A. (June 1998). "Rethinking environmental management". Progress in Human Geography 22 (3): 321–343. doi:10.1191/030913298672031592.

- ↑ Fazey, Ioan; Fazey, John A.; Salisbury, Janet G.; Lindenmayer, David B.; Dovers, Steve (2006). "The nature and role of experiential knowledge for environmental conservation". Environmental Conservation 33: 1–10. doi:10.1017/S037689290600275X. http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/bitstream/10023/1629/1/Fazey2006EnvironmentalConservation33ExperientialKnowledge.pdf.

- ↑ Bell, Simon; Morse, Stephen (2005). "Delivering sustainability therapy in sustainable development projects". Journal of Environmental Management 75 (1): 37–51. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.11.006. PMID 15748802. http://oro.open.ac.uk/120/1/Deliv._Sus_Bell__Morse_JEM051.pdf.

- ↑ Avolio, Bruce J.; Avey, James B.; Quisenberry, David (August 2010). "Estimating return on leadership development investment". The Leadership Quarterly 21 (4): 633–644. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.06.006. http://uwtv.org/files/2013/01/roldleaqua650.pdf.

- ↑ Turesky, Elizabeth Fisher; Gallagher, Dennis (June 2011). "Know thyself: coaching for leadership using Kolb's experiential learning theory". The Coaching Psychologist 7 (1): 5–14. http://people.usm.maine.edu/eturesky/Articles/KnowThyself.pdf.

- ↑ Mezirow, Jack (Summer 1997). "Transformative learning: theory to practice". New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1997 (74): 5–12. doi:10.1002/ace.7401. http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/~ntzcl1/literature/elearning/mezirow.pdf.

- ↑ Helsing, Deborah; Howell, Annie; Kegan, Robert; Lahey, Lisa Laskow (Fall 2008). "Putting the 'development' in professional development: understanding and overturning educational leaders' immunities to change". Harvard Educational Review 78 (3): 437–465. doi:10.17763/haer.78.3.888l759g1qm54660. http://www.bostonpublicschools.org/cms/lib07/MA01906464/Centricity/Domain/142/Kegan%20-%20Putting%20the%20Professional%20Development%20in%20PD.pdf.

- ↑ Somerville, David; Keeling, June (24 March 2004). "A practical approach to promote reflective practice within nursing". Nursing Times 100 (12): 42–45. PMID 15067912. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/nurse-educators/a-practical-approach-to-promote-reflective-practice-within-nursing-23-03-2004/.

External links

| Library resources about reflective practice |

- McDowell, Ceasar; Canepa, Claudia; Ferriera, Sebastiao (January 2007). "Reflective practice: an approach for expanding your learning frontiers". MIT OpenCourseWare. http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/urban-studies-and-planning/11-965-reflective-practice-an-approach-for-expanding-your-learning-frontiers-january-iap-2007/.

- Neill, James (14 November 2010). "Experiential learning cycles: overview of 9 experiential learning cycle models". Wilderdom.com. http://wilderdom.com/experiential/elc/ExperientialLearningCycle.htm.

- Smith, Mark K.. "Reflective practice". The encyclopedia of informal education. http://infed.org/mobi/category/reflective-practice/.

KSF

KSF