Resource consent

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

A resource consent is the authorisation given to certain activities or uses of natural and physical resources required under the New Zealand Resource Management Act (the "RMA"). Some activities may either be specifically authorised by the RMA [1] or be permitted activities authorised by rules in plans.[2] Any activities that are not permitted by the RMA, or by a rule in a plan, require a resource consent before they are carried out.

Definition and nature

The term "resource consent" is defined as;

- a permit to carry out an activity that would otherwise contravene a rule in a city or district plan.

- a permission required for an activity that might affect the environment, and that isn't allowed 'as of right' in the district or regional plan.[3]

A resource consent, once granted to an applicant, is neither real nor personal property.[4] Therefore, resource consents cannot be 'owned'; they are 'held' by 'consent holders'.[5]

Types

A resource consent means any of the following:[6]

- land use consent (Section 9 and 13)

- subdivision consent (Section 11)

- water permit (Section 14)

- discharge permit (Section 15)

- coastal permit. (Section 12)

Plan classifications

Regional and district plans may give an activity that requires a resource consent one of six possible classifications.[7]

| Activity Classification | Consent required | Consent must be granted | Consent can be granted | Consideration restricted | Effects must be minor | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permitted | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Activity allowed without a consent |

| Controlled | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Authority must grant consent, but may impose conditions in some matters |

| Restricted discretionary | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Authority may deny or grant consent, with conditions, but only decided on matters set out in the plan. |

| Discretionary | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Authority has full discretion to deny or grant consent, and may impose conditions. |

| Non-complying | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Authority may deny or grant consent, where effects are minor and activity not inconsistent with plan. |

| Prohibited | N/A | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | Plan change required to reclassify |

The above table is of a very summary nature, and exceptions apply in some circumstances.

There are two further classifications, restricted coastal activity and recognised customary activity, which are subject to particular conditions.

Application process

Applications for resource consents are usually granted by the regional councils and territorial authorities acting as consent authorities. Any person may apply for a resource consent.[8] Applications must be in the prescribed form and include an assessment of environmental effects.[9] The resource consent process is designed to enable environmental managers to consider environmental issues associated with particular proposals for resource use.[10]

While this principle is commendable, there is a complexity of issues that surround assessing the effects on the environment of a consent application and the consideration of applications (e.g. social, cultural, and ecological considerations, significance of effects, the place of community values, the sufficiency of evidence and the onus of proof).

A resource consent may be granted with a set of conditions that need to be complied with in order to ensure minimal environmental effect.[11]

Appeals

Decisions on resource consent applications may be appealed [12] to the Environment Court (formerly the Planning Tribunal until 1993). Appeals are considered on a 'de novo' basis, where the Environment Court hears any evidence it requires and makes its own decision which replaces that of the local authority.[13] Decisions of the Environment Court may only be appealed to the High Court of New Zealand on a point of law.[14]

Statistics

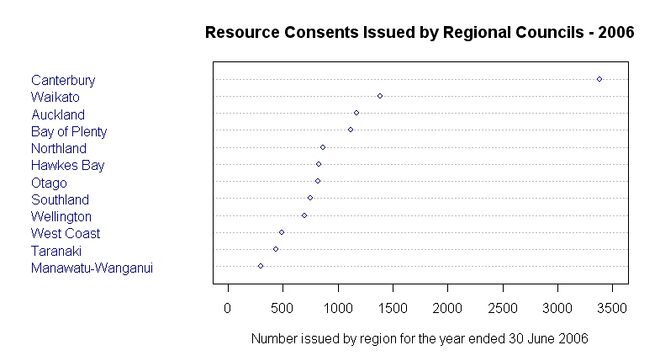

Of New Zealand's regional councils and unitary authorities, Canterbury Regional Council receives and processes the most applications for resource consents. In the year ended 30 June 2006, Canterbury Regional Council processed 3,381 applications, more than double the number processed by any other consent authority. Environment Waikato had the next highest number; 1,384 applications in 2006.[15]

Criticism

One of the major complaints (mainly raised by corporations) regarding the resource consent process has been that submissions made in opposition against a project can be made by any entity, even if it is not affected. This has, in the opinion of the critics, caused the resource consent process to be used as an anti-competitive and anti-investment tool by which both individuals and other corporations can stop projects while appearing to act in the common interest. The true motivation of such submissions and associated appeals, it is alleged, is trade competition, a factor which is expressly not to be considered when testing the merits of a resource consent application.[16]

Other criticisms include:

- Many minor activities which do not appear to change the use of any resources or have any environmental impact require a consent, such as building a deck within a certain distance of a boundary or certain renovations within existing houses.

- the long time taken for consents to be granted adds weeks or months to the planning and building of projects

- the cost of the consents - the absolute minimum cost of a consent at the Wellington District Council is five hours at 90 dollars per hour. Together with the cost of preparing reports, employing special inspectors and designers, and complying with the conditions of a consent, the costs of obtaining a resource consent can substantially increase the costs of both small and large projects to the point where it is no longer economical to proceed with the activity (for instance, constructing a deck or building a new driveway) even though it would add value to the property.

Some commentators consider that the requirement for resource consents is slowing or preventing the construction of large infrastructure projects, such as highways, roads, wind farms and other power generation plants, which are important to New Zealand's economic wellbeing, as well as adding to the cost of such projects.[citation needed]

Proposed 2009 reforms

In February 2009 the National-led government announced the Resource Management (Simplify & Streamline) Amendment Bill which seeks to improve the resource consent process.[17]

See also

- Environment of New Zealand

References

- ↑ Sections 9 to 15 Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Section 77B(1) Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Appendix 4: Glossary of RMA Terms Your Guide to the Resource Management Act, updated August 2006, Ref. ME7662, retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ↑ Section 122(1) Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ The Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand) specifically refers to 'consent holders'. See Sections 120(1)(a), 122, 124, 127, 128, 129, 130, 132, 136, and 138.

- ↑ Section 87 Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Sections 77B(1) to 77B(7) Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Section 88() Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Section 88(2) Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Birdsong, B. (1998) Adjudicating Sustainability: The Environment Court and New Zealand's Resource Management Act , Prepared by Bret Birdsong October 1998 copyright © Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowship in Public Policy, page 13.

- ↑ Section 108, Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Section 120 Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ Birdsong, B. (1998), page 22.

- ↑ Section 299 Resource Management Act 1991 (New Zealand)

- ↑ RMA Survey of Local Authorities: 2005/2006 survey, Ministry for the Environment, Ref. ME797, Appendix One.

- ↑ Eriksen, Alanah (21 February 2008). "Mayor wants development objections limited". New Zealand Herald News. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10493591. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ "Reform tackles costs, uncertainties and delays of RMA". New Zealand Government. 2009-02-03. http://beehive.govt.nz/release/reform+tackles+costs+uncertainties+and+delays+rma. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

External links

- Resource Management Act 1991 - text of the Act

- Ministry for the Environment - resource consent information

|

KSF

KSF