The Holocaust

Topic: Social

From HandWiki - Reading time: 93 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 93 min

| The Holocaust | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |

From the Auschwitz Album: Hungarian Jews arriving at Auschwitz II in German-occupied Poland, May 1944. Most were "selected" to go to the gas chambers. Camp prisoners are visible in their striped uniforms.[1] | |

| Location | Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe |

| Description | Genocide of the European Jews |

| Date | 1941–1945[2] |

Attack type | Genocide, ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths |

|

| Perpetrators | Nazi Germany and its collaborators List of major perpetrators of the Holocaust |

| Motive | Antisemitism, racism |

| Trials | Nuremberg trials, Subsequent Nuremberg trials, Trial of Adolf Eichmann, and others |

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah,[lower-alpha 3] was the World War II genocide of the European Jews. Between 1941 and 1945, across German-occupied Europe, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews, around two-thirds of Europe's Jewish population.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 4] The murders were carried out in pogroms and mass shootings; by a policy of extermination through work in concentration camps; and in gas chambers and gas vans in German extermination camps, chiefly Auschwitz, Bełżec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibór, and Treblinka in occupied Poland.[4]

Germany implemented the persecution in stages. Following Adolf Hitler's appointment as Chancellor on 30 January 1933, the regime built a network of concentration camps in Germany for political opponents and those deemed "undesirable", starting with Dachau on 22 March 1933.[5] After the passing of the Enabling Act on 24 March,[6] which gave Hitler plenary powers, the government began isolating Jews from civil society; this included boycotting Jewish businesses in April 1933 and enacting the Nuremberg Laws in September 1935. On 9–10 November 1938, eight months after Germany annexed Austria, Jewish businesses and other buildings were ransacked or set on fire throughout Germany and Austria during what became known as Kristallnacht (the "Night of Broken Glass"). After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, triggering World War II, the regime set up ghettos to segregate Jews. Eventually thousands of camps and other detention sites were established across German-occupied Europe.

The segregation of Jews in ghettos culminated in the policy of extermination the Nazis called the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question", discussed by senior Nazi officials at the Wannsee Conference in Berlin in January 1942. As German forces captured territories in the East, all anti-Jewish measures were radicalized. Under the coordination of the SS, with directions from the highest leadership of the Nazi Party, killings were committed within Germany itself, throughout occupied Europe, and within territories controlled by Germany's allies. Paramilitary death squads called Einsatzgruppen, in cooperation with the German Army and local collaborators, murdered around 1.3 million Jews in mass shootings and pogroms between 1941 and 1945. By mid-1942, victims were being deported from ghettos across Europe in sealed freight trains to extermination camps where, if they survived the journey, they were gassed, worked or beaten to death, or killed by disease or during death marches. The killing continued until the end of World War II in Europe in May 1945.

The European Jews were targeted for extermination as part of a larger event during the Holocaust era (1933–1945),[7][8] in which Germany and its collaborators persecuted and murdered other groups, including ethnic Poles, Soviet civilians and prisoners of war, the Roma, the handicapped, political and religious dissidents, and gay men.[lower-alpha 5] The death toll of these other groups is thought to be over 11 million.[lower-alpha 2]

Terminology and scope

Terminology

The term holocaust, first used in 1895 by the The New York Times to describe the massacre of Armenian Christians by Ottoman Muslims,[9] comes from the Greek: ὁλόκαυστος, romanized: holókaustos; ὅλος hólos, "whole" + καυστός kaustós, "burnt offering".[lower-alpha 6] The biblical term shoah (Hebrew: שׁוֹאָה), meaning "destruction", became the standard Hebrew term for the murder of the European Jews. According to Haaretz, the writer Yehuda Erez may have been the first to describe events in Germany as the shoah. Davar and later Haaretz both used the term in September 1939.[12][lower-alpha 7] Yom HaShoah became Israel's Holocaust Remembrance Day in 1951.[14]

On 3 October 1941 the American Hebrew used the phrase "before the Holocaust", apparently to refer to the situation in France,[15] and in May 1943 the New York Times, discussing the Bermuda Conference, referred to the "hundreds of thousands of European Jews still surviving the Nazi Holocaust".[16] In 1968 the Library of Congress created a new category, "Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)".[17] The term was popularized in the United States by the NBC mini-series Holocaust (1978), about a fictional family of German Jews,[18] and in November that year the President's Commission on the Holocaust was established.[19] As non-Jewish groups began to include themselves as Holocaust victims, many Jews chose to use the Hebrew terms Shoah or Churban.[20][lower-alpha 8] The Nazis used the phrase "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" (German: die Endlösung der Judenfrage).[22]

Definition

Most Holocaust historians define the Holocaust as the genocide of the European Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1941 and 1945.[lower-alpha 1]

Michael Gray, a specialist in Holocaust education,[30] offers three definitions: (a) "the persecution and murder of Jews by the Nazis and their collaborators between 1933 and 1945", which views Kristallnacht in 1938 as an early phase of the Holocaust; (b) "the systematic mass murder of the Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators between 1941 and 1945", which recognizes the policy shift in 1941 toward extermination; and (c) "the persecution and murder of various groups by the Nazi regime and its collaborators between 1933 and 1945", which includes all the Nazis' victims, a definition that fails, Gray writes, to acknowledge that only the Jews were singled out for annihilation.[31] Donald Niewyk and Francis Nicosia, in The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (2000), favor a definition that focuses on the Jews, Roma and handicapped: "the systematic, state-sponsored murder of entire groups determined by heredity".[32]

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum distinguishes between the Holocaust (the murder of six million Jews) and "the era of the Holocaust", which began when Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933.[33] Victims of the era of the Holocaust include those the Nazis viewed as inherently inferior (chiefly Slavs, the Roma and the handicapped), and those targeted because of their beliefs or behavior (such as Jehovah's Witnesses, communists and homosexuals).[34] Peter Hayes writes that the persecution of these groups was less consistent than that of the Jews; the Nazis' treatment of the Slavs, for example, consisted of "enslavement and gradual attrition", while some Slavs (Hayes lists Bulgarians, Croats, Slovaks and some Ukrainians) were favored.[24] Against this, Hitler regarded the Jews as what Dan Stone calls "a Gegenrasse: a 'counter-race' ... not really human at all".[lower-alpha 5]

Distinctive features

Genocidal state

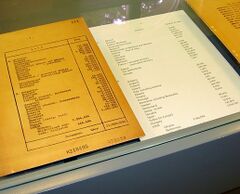

The logistics of the mass murder turned Germany into what Michael Berenbaum called a "genocidal state".[36] Eberhard Jäckel wrote in 1986 during the German Historikerstreit—a dispute among historians about the uniqueness of the Holocaust and its relationship with the crimes of the Soviet Union—that it was the first time a state had thrown its power behind the idea that an entire people should be wiped out.[lower-alpha 9] Anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was to be exterminated,[38] and complex rules were devised to deal with Mischlinge ("mixed breeds").[39] Bureaucrats identified who was a Jew, confiscated property, and scheduled trains to deport them. Companies fired Jews and later used them as slave labor. Universities dismissed Jewish faculty and students. German pharmaceutical companies tested drugs on camp prisoners; other companies built the crematoria.[36] As prisoners entered the death camps, they surrendered all personal property,[40] which was catalogued and tagged before being sent to Germany for reuse or recycling.[41] Through a concealed account, the German National Bank helped launder valuables stolen from the victims.[42]

Collaboration

Dan Stone writes that since the opening of archives following the fall of former communist states in Eastern Europe, it has become increasingly clear that the Holocaust was a pan-European phenomenon, a series of "Holocausts" impossible to conduct without the help of local collaborators. Without collaborators, the Germans could not have extended the killing across most of the continent.[43][lower-alpha 10][45] According to Donald Bloxham, in many parts of Europe "extreme collective violence was becoming an accepted measure of resolving identity crises".[46] Christian Gerlach writes that non-Germans "not under German command" killed 5–6 percent of the six million, but that their involvement was crucial in other ways.[47]

The industrialization and scale of the murder was unprecedented. Killings were systematically conducted in virtually all areas of occupied Europe—more than 20 occupied countries.[48] Nearly three million Jews in occupied Poland and between 700,000 and 2.5 million Jews in the Soviet Union were killed. Hundreds of thousands more died in the rest of Europe.[49] Some Christian churches defended converted Jews, but otherwise, Saul Friedländer wrote in 2007: "Not one social group, not one religious community, not one scholarly institution or professional association in Germany and throughout Europe declared its solidarity with the Jews ..."[50]

Medical experiments

Medical experiments conducted on camp inmates by the SS were another distinctive feature.[51] At least 7,000 prisoners were subjected to experiments; most died as a result, during the experiments or later.[52] Twenty-three senior physicians and other medical personnel were charged at Nuremberg, after the war, with crimes against humanity. They included the head of the German Red Cross, tenured professors, clinic directors, and biomedical researchers.[53] Experiments took place at Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Natzweiler-Struthof, Neuengamme, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, and elsewhere. Some dealt with sterilization of men and women, the treatment of war wounds, ways to counteract chemical weapons, research into new vaccines and drugs, and the survival of harsh conditions.[52]

The most notorious physician was Josef Mengele, an SS officer who became the Auschwitz camp doctor on 30 May 1943.[54] Interested in genetics[54] and keen to experiment on twins, he would pick out subjects from the new arrivals during "selection" on the ramp, shouting "Zwillinge heraus!" (twins step forward!).[55] They would be measured, killed, and dissected. One of Mengele's assistants said in 1946 that he was told to send organs of interest to the directors of the "Anthropological Institute in Berlin-Dahlem". This is thought to refer to Mengele's academic supervisor, Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, director from October 1942 of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Berlin-Dahlem.[56][lower-alpha 11]

Jews in Europe

| Country | Number of Jews (pre-war) |

Source |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 185,000–192,000 | [49] |

| Belgium | 55,000–70,000 | [49] |

| Bulgaria | 50,000 | [49] |

| Czechoslovakia | 357,000 | [58] |

| Denmark (1933) | 5,700 | [59] |

| Estonia | 4,500 | [49] |

| Finland | 2,000 | [49] |

| France | 330,000–350,000 | [49] |

| Germany (1933) | 523,000–525,000 | [49] |

| Greece | 77,380 | [49] |

| Hungary | 725,000–825,000 | [49] |

| Italy | 42,500–44,500 | [49] |

| Latvia | 91,500–95,000 | [49] |

| Lithuania | 168,000 | [49] |

| Netherlands | 140,000 | [49] |

| Poland | 3,300,000–3,500,000 | [49] |

| Romania (1930) | 756,000 | [49] |

| Soviet Union | 3,020,000 | [49] |

| Sweden (1933) | 6,700 | [59] |

| United Kingdom | 300,000 | [58] |

| Yugoslavia | 78,000–82,242 | [49] |

There were around 9.5 million Jews in Europe in 1933.[60] Most heavily concentrated in the east, the pre-war population was 3.5 million in Poland; 3 million in the Soviet Union; nearly 800,000 in Romania, and 700,000 in Hungary. Germany had over 500,000.[49]

Origins

Antisemitism and the völkisch movement

Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, Jews were subjected to antisemitism based on Christian theology, which blamed them for killing Jesus. Even after the Reformation, Catholicism and Lutheranism continued to persecute Jews, accusing them of blood libels and subjecting them to pogroms and expulsions.[61] The second half of the 19th century saw the emergence in the German empire and Austria-Hungary of the völkisch movement, developed by such thinkers as Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Paul de Lagarde. The movement embraced a pseudo-scientific racism that viewed Jews as a race whose members were locked in mortal combat with the Aryan race for world domination.[62] These ideas became commonplace throughout Germany; the professional classes adopted an ideology that did not see humans as racial equals with equal hereditary value.[63] The Nazi Party (the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or National Socialist German Workers' Party) originated as an offshoot of the völkisch movement, and it adopted that movement's antisemitism.[64]

Germany after World War I, Hitler's world view

After World War I (1914–1918), many Germans did not accept that their country had been defeated, which gave birth to the stab-in-the-back myth. This insinuated that it was disloyal politicians, chiefly Jews and communists, who had orchestrated Germany's surrender. Inflaming the anti-Jewish sentiment was the apparent over-representation of Jews in the leadership of communist revolutionary governments in Europe, such as Ernst Toller, head of a short-lived revolutionary government in Bavaria. This perception contributed to the canard of Jewish Bolshevism.[65]

Early antisemites in the Nazi Party included Dietrich Eckart, publisher of the Völkischer Beobachter, the party's newspaper, and Alfred Rosenberg, who wrote antisemitic articles for it in the 1920s. Rosenberg's vision of a secretive Jewish conspiracy ruling the world would influence Hitler's views of Jews by making them the driving force behind communism.[66] Central to Hitler's world view was the idea of expansion and lebensraum (living space) in Eastern Europe for German Aryans, a policy of what Doris Bergen called "race and space". Open about his hatred of Jews, he subscribed to common antisemitic stereotypes.[67] From the early 1920s onwards, he compared the Jews to germs and said they should be dealt with in the same way. He viewed Marxism as a Jewish doctrine, said he was fighting against "Jewish Marxism", and believed that Jews had created communism as part of a conspiracy to destroy Germany.[68]

Rise of Nazi Germany

Dictatorship and repression (1933–1939)

With the appointment in January 1933 of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany and the Nazi's seizure of power, German leaders proclaimed the rebirth of the Volksgemeinschaft ("people's community").[70] Nazi policies divided the population into two groups: the Volksgenossen ("national comrades") who belonged to the Volksgemeinschaft, and the Gemeinschaftsfremde ("community aliens") who did not. Enemies were divided into three groups: the "racial" or "blood" enemies, such as the Jews and Roma; political opponents of Nazism, such as Marxists, liberals, Christians, and the "reactionaries" viewed as wayward "national comrades"; and moral opponents, such as gay men, the work-shy, and habitual criminals. The latter two groups were to be sent to concentration camps for "re-education", with the aim of eventual absorption into the Volksgemeinschaft. "Racial" enemies could never belong to the Volksgemeinschaft; they were to be removed from society.[71]

Before and after the March 1933 Reichstag elections, the Nazis intensified their campaign of violence against opponents,[72] setting up concentration camps for extrajudicial imprisonment.[73] One of the first, at Dachau, opened on 22 March 1933.[74] Initially the camp contained mostly Communists and Social Democrats.[75] Other early prisons were consolidated by mid-1934 into purpose-built camps outside the cities, run exclusively by the SS.[76] The camps served as a deterrent by terrorizing Germans who did not support the regime.[77]

Throughout the 1930s, the legal, economic, and social rights of Jews were steadily restricted.[78]On 1 April 1933, there was a boycott of Jewish businesses.[79] On 7 April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was passed, which excluded Jews and other "non-Aryans" from the civil service.[80] Jews were disbarred from practicing law, being editors or proprietors of newspapers, joining the Journalists' Association, or owning farms.[81] In Silesia, in March 1933, a group of men entered the courthouse and beat up Jewish lawyers; Friedländer writes that, in Dresden, Jewish lawyers and judges were dragged out of courtrooms during trials.[82] Jewish students were restricted by quotas from attending schools and universities.[80] Jewish businesses were targeted for closure or "Aryanization", the forcible sale to Germans; of the approximately 50,000 Jewish-owned businesses in Germany in 1933, about 7,000 were still Jewish-owned in April 1939. Works by Jewish composers,[83] authors, and artists were excluded from publications, performances, and exhibitions.[84] Jewish doctors were dismissed or urged to resign. The Deutsches Ärzteblatt (a medical journal) reported on 6 April 1933: "Germans are to be treated by Germans only."[85]

Sterilization Law, Aktion T4

The economic strain of the Great Depression led Protestant charities and some members of the German medical establishment to advocate compulsory sterilization of the "incurable" mentally and physically handicapped,[87] people the Nazis called Lebensunwertes Leben (life unworthy of life).[88] On 14 July 1933, the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses), the Sterilization Law, was passed.[89][90] The New York Times reported on 21 December that year: "400,000 Germans to be sterilized".[91] There were 84,525 applications from doctors in the first year. The courts reached a decision in 64,499 of those cases; 56,244 were in favor of sterilization.[92] Estimates for the number of involuntary sterilizations during the whole of the Third Reich range from 300,000 to 400,000.[93]

In October 1939 Hitler signed a "euthanasia decree" backdated to 1 September 1939 that authorized Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler, the chief of Hitler's Chancellery, and Karl Brandt, Hitler's personal physician, to carry out a program of involuntary euthanasia. After the war this program came to be known as Aktion T4,[94] named after Tiergartenstraße 4, the address of a villa in the Berlin borough of Tiergarten, where the various organizations involved were headquartered.[95] T4 was mainly directed at adults, but the euthanasia of children was also carried out.[96] Between 1939 and 1941, 80,000 to 100,000 mentally ill adults in institutions were killed, as were 5,000 children and 1,000 Jews, also in institutions. There were also dedicated killing centers, where the deaths were estimated at 20,000, according to Georg Renno, deputy director of Schloss Hartheim, one of the euthanasia centers, or 400,000, according to Frank Zeireis, commandant of the Mauthausen concentration camp.[97] Overall, the number of mentally and physically handicapped murdered was about 150,000.[98]

Although not ordered to take part, psychiatrists and many psychiatric institutions were involved in the planning and carrying out of Aktion T4.[99] In August 1941, after protests from Germany's Catholic and Protestant churches, Hitler cancelled the T4 program,[100] although the handicapped continued to be killed until the end of the war.[98] The medical community regularly received bodies for research; for example, the University of Tübingen received 1,077 bodies from executions between 1933 and 1945. The German neuroscientist Julius Hallervorden received 697 brains from one hospital between 1940 and 1944: "I accepted these brains of course. Where they came from and how they came to me was really none of my business."[101]

Nuremberg Laws, Jewish emigration

On 15 September 1935, the Reichstag passed the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, known as the Nuremberg Laws. The former said that only those of "German or kindred blood" could be citizens. Anyone with three or more Jewish grandparents was classified as a Jew.[103] The second law said: "Marriages between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden." Sexual relationships between them were also criminalized; Jews were not allowed to employ German women under the age of 45 in their homes.[104][103] The laws referred to Jews but applied equally to the Roma and black Germans. Although other European countries—Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Slovakia, and Vichy France—passed similar legislation,[103] Gerlach notes that "Nazi Germany adopted more nationwide anti-Jewish laws and regulations (about 1,500) than any other state."[105]

By the end of 1934, 50,000 German Jews had left Germany,[106] and by the end of 1938, approximately half the German Jewish population had left,[107] among them the conductor Bruno Walter, who fled after being told that the hall of the Berlin Philharmonic would be burned down if he conducted a concert there.[108] Albert Einstein, who was in the United States when Hitler came to power, never returned to Germany; his citizenship was revoked and he was expelled from the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and Prussian Academy of Sciences.[109] Other Jewish scientists, including Gustav Hertz, lost their teaching positions and left the country.[110]

Anschluss

On 12 March 1938, Germany annexed Austria. Austrian Nazis broke into Jewish shops, stole from Jewish homes and businesses, and forced Jews to perform humiliating acts such as scrubbing the streets or cleaning toilets.[111] Jewish businesses were "Aryanized", and all the legal restrictions on Jews in Germany were imposed.[112] In August that year, Adolf Eichmann was put in charge of the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna (Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung in Wien). About 100,000 Austrian Jews had left the country by May 1939, including Sigmund Freud and his family, who moved to London.[113] The Évian Conference was held in France in July 1938 by 32 countries, as an attempt to help the increased refugees from Germany, but aside from establishing the largely ineffectual Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, little was accomplished and most countries participating did not increase the number of refugees they would accept.[114]

Kristallnacht

On 7 November 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew, shot the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in the German Embassy in Paris, in retaliation for the expulsion of his parents and siblings from Germany.[115][lower-alpha 12] When vom Rath died on 9 November, the government used his death as a pretext to instigate a pogrom against the Jews. The government claimed it was spontaneous, but in fact it had been ordered and planned by Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, although with no clear goals, according to David Cesarani. The result, he writes, was "murder, rape, looting, destruction of property, and terror on an unprecedented scale".[117]

Known as Kristallnacht (or "Night of Broken Glass"), the attacks on 9–10 November 1938 were partly carried out by the SS and SA,[118] but ordinary Germans joined in; in some areas, the violence began before the SS or SA arrived.[119] Over 7,500 Jewish shops (out of 9,000) were looted and attacked, and over 1,000 synagogues damaged or destroyed. Groups of Jews were forced by the crowd to watch their synagogues burn; in Bensheim they were made to dance around it, and in Laupheim to kneel before it.[120] At least 90 Jews died. The damage was estimated at 39 million Reichmarks.[121] Cesarani writes that "[t]he extent of the desolation stunned the population and rocked the regime."[122] It also shocked the rest of the world. The Times of London wrote on 11 November 1938: "No foreign propagandist bent upon blackening Germany before the world could outdo the tale of burnings and beatings, of blackguardly assaults upon defenseless and innocent people, which disgraced that country yesterday. Either the German authorities were a party to this outbreak or their powers over public order and a hooligan minority are not what they are proudly claimed to be."[123]

Between 9 and 16 November, 30,000 Jews were sent to the Buchenwald, Dachau, and Sachsenhausen concentration camps.[124] Many were released within weeks; by early 1939, 2,000 remained in the camps.[125] German Jewry was held collectively responsible for restitution of the damage; they also had to pay an "atonement tax" of over a billion Reichmarks. Insurance payments for damage to their property were confiscated by the government. A decree on 12 November 1938 barred Jews from most remaining occupations.[126] Kristallnacht marked the end of any sort of public Jewish activity and culture, and Jews stepped up their efforts to leave the country.[127]

Resettlement

Before World War II, Germany considered mass deportation from Europe of German, and later European, Jewry.[128] Among the areas considered for possible resettlement were British Palestine and, after the war began, French Madagascar,[129] Siberia, and two reservations in Poland.[130][lower-alpha 13] Palestine was the only location to which any German resettlement plan produced results, via the Haavara Agreement between the Zionist Federation of Germany and the German government. Between November 1933 and December 1939, the agreement resulted in the emigration of about 53,000 German Jews, who were allowed to transfer RM 100 million of their assets to Palestine by buying German goods, in violation of the Jewish-led anti-Nazi boycott of 1933.[132]

Beginning of World War II

Invasion of Poland

Einsatzgruppen, pogroms

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, triggering a declaration of war from France and the UK, it gained control of an additional two million Jews, reduced to around 1.7 – 1.8 million in the German zone when the Soviet Union invaded from the east on 17 September.[133] The German army, the Wehrmacht, was accompanied by seven SS Einsatzgruppen ("special task forces") and an Einsatzkommando, numbering altogether 3,000 men, whose role was to deal with "all anti-German elements in hostile country behind the troops in combat". Most of the Einsatzgruppen commanders were professionals; 15 of the 25 leaders had PhDs. By 29 August, two days before the invasion, they had already drawn up a list of 30,000 people to send to concentration camps. By the first week of the invasion, 200 people were being executed every day.[134]

The Germans began sending Jews from territories they had recently annexed (Austria, Czechoslovakia, and western Poland) to the central section of Poland, which they called the General Government.[135] To make it easier to control and deport them, the Jews were concentrated in ghettos in major cities.[136] The Germans planned to set up a Jewish reservation in southeast Poland around the transit camp in Nisko, but the "Nisko plan" failed, in part because it was opposed by Hans Frank, the new Governor-General of the General Government.[137] In mid-October 1940 the idea was revived, this time to be located in Lublin. Resettlement continued until January 1941 under SS officer Odilo Globocnik, but further plans for the Lublin reservation failed for logistical and political reasons.[138]

There had been anti-Jewish pogroms in Poland before the war, including in around 100 towns between 1935 and 1937,[139] and again in 1938.[140] In June and July 1941, during the Lviv pogroms in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), around 6,000 Polish Jews were murdered in the streets by the Ukrainian People's Militia and local people.[141][lower-alpha 14] Another 2,500–3,500 Jews died in mass shootings by Einsatzgruppe C.[142] During the Jedwabne pogrom on 10 July 1941, a group of Poles in Jedwabne killed the town's Jewish community, many of whom were burned alive in a barn.[143] The attack may have been engineered by the German Security Police.[144][lower-alpha 15]

Ghettos, Jewish councils

- Main ghettos: Białystok, Budapest, Kraków, Kovno, Łódź, Lvov, Riga, Vilna, Warsaw (Warsaw ghetto uprising)

The Germans established ghettos in Poland, in the incorporated territories and General Government area, to confine Jews.[135] These were closed off from the outside world at different times and for different reasons.[146] In early 1941, the Warsaw ghetto contained 445,000 people, including 130,000 from elsewhere,[147] while the second largest, the Łódź ghetto, held 160,000.[148] Although the Warsaw ghetto contained 30 percent of the city's population, it occupied only 2.5 percent of its area, averaging over nine people per room.[149] The massive overcrowding, poor hygiene facilities and lack of food killed thousands. Over 43,000 residents died in 1941.[150]

According to a letter dated 21 September 1939 from SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA or Reich Security Head Office), to the Einsatzgruppen, each ghetto had to be run by a Judenrat, or "Jewish Council of Elders", to consist of 24 male Jews with local influence.[151] Judenräte were responsible for the ghetto's day-to-day operations, including distributing food, water, heat, medical care, and shelter. The Germans also required them to confiscate property, organize forced labor, and, finally, facilitate deportations to extermination camps.[152] The Jewish councils' basic strategy was one of trying to minimize losses by cooperating with German authorities, bribing officials, and petitioning for better conditions.[153]

Invasion of Norway and Denmark

Germany invaded Norway and Denmark on 9 April 1940, during Operation Weserübung. Denmark was overrun so quickly that there was no time for a resistance to form. Consequently, the Danish government stayed in power and the Germans found it easier to work through it. Because of this, few measures were taken against the Danish Jews before 1942.[154] By June 1940 Norway was completely occupied.[155] In late 1940, the country's 1,800 Jews were banned from certain occupations, and in 1941 all Jews had to register their property with the government.[156] On 26 November 1942, 532 Jews were taken by police officers, at four o'clock in the morning, to Oslo harbor, where they boarded a German ship. From Germany they were sent by freight train to Auschwitz. According to Dan Stone, only nine survived the war.[157]

Invasion of France and the Low Countries

In May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France. After Belgium's surrender, the country was ruled by a German military governor, Alexander von Falkenhausen, who enacted anti-Jewish measures against its 90,000 Jews, many of them refugees from Germany or Eastern Europe.[158] In the Netherlands, the Germans installed Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Reichskommissar, who began to persecute the country's 140,000 Jews. Jews were forced out of their jobs and had to register with the government. In February 1941, non-Jewish Dutch citizens staged a strike in protest that was quickly crushed.[159] From July 1942, over 107,000 Dutch Jews were deported; only 5,000 survived the war. Most were sent to Auschwitz; the first transport of 1,135 Jews left Holland for Auschwitz on 15 July 1942. Between 2 March and 20 July 1943, 34,313 Jews were sent in 19 transports to the Sobibór extermination camp, where all but 18 are thought to have been gassed on arrival.[160]

France had approximately 300,000 Jews, divided between the German-occupied north and the unoccupied collaborationist southern areas in Vichy France (named after the town Vichy). The occupied regions were under the control of a military governor, and there, anti-Jewish measures were not enacted as quickly as they were in the Vichy-controlled areas.[161] In July 1940, the Jews in the parts of Alsace-Lorraine that had been annexed to Germany were expelled into Vichy France.[162] Vichy France's government implemented anti-Jewish measures in French Algeria and the two French Protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco.[163] Tunisia had 85,000 Jews when the Germans and Italians arrived in November 1942; an estimated 5,000 Jews were subjected to forced labor.[164]

The fall of France gave rise to the Madagascar Plan in the summer of 1940, when French Madagascar in Southeast Africa became the focus of discussions about deporting all European Jews there; it was thought that the area's harsh living conditions would hasten deaths.[165] Several Polish, French and British leaders had discussed the idea in the 1930s, as did German leaders from 1938.[166] Adolf Eichmann's office was ordered to investigate the option, but no evidence of planning exists until after the defeat of France in June 1940.[167] Germany's inability to defeat Britain, something that was obvious to the Germans by September 1940, prevented the movement of Jews across the seas,[168] and the Foreign Ministry abandoned the plan in February 1942.[169]

Invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece

Yugoslavia and Greece were invaded in April 1941 and surrendered before the end of the month. Germany and Italy divided Greece into occupation zones but did not eliminate it as a country. Yugoslavia, home to around 80,000 Jews, was dismembered; regions in the north were annexed by Germany and regions along the coast made part of Italy. The rest of the country was divided into the Independent State of Croatia, nominally an ally of Germany, and Serbia, which was governed by a combination of military and police administrators.[170] Serbia was declared free of Jews (Judenfrei) in August 1942.[171][172] Croatia's ruling party, the Ustashe, killed the majority of the country's Jews and massacred, expelled or forcibly converted to Catholicism the area's local Orthodox Christian Serb population.[173] On 18 April 1944 Croatia was declared as Judenfrei.[174][175] Jews and Serbs alike were "hacked to death and burned in barns", writes historian Jeremy Black. One difference between the Germans and Croatians was that the Ustashe allowed its Jewish and Serbian victims to convert to Catholicism so they could escape death.[171] According to Jozo Tomasevich of the 115 Jewish religious communities from Yugoslavia which existed in 1939 and 1940, only the Jewish communities from Zagreb managed to survive the war.[176]

Invasion of the Soviet Union

Reasons

Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, a day Timothy Snyder called "one of the most significant days in the history of Europe ... the beginning of a calamity that defies description".[177] Jürgen Matthäus described it as "a quantum leap toward the Holocaust".[178] German propaganda portrayed the conflict as an ideological war between German National Socialism and Jewish Bolshevism and as a racial war between the Germans and the Jewish, Romani, and Slavic Untermenschen ("sub-humans").[179] David Cesarani writes that the war was driven primarily by the need for resources: agricultural land to feed Germany, natural resources for German industry, and control over Europe's largest oil fields. But precisely because of the Soviet Union's vast resources, "[v]ictory would have to be swift".[180] Between early fall 1941 and late spring 1942, according to Matthäus, 2 million of the 3.5 million Soviet soldiers captured by the Wehrmacht (Germany's armed forces) had been executed or had died of neglect and abuse. By 1944 the Soviet death toll was at least 20 million.[181]

Mass shootings

As German troops advanced, the mass shooting of "anti-German elements" was assigned, as in Poland, to the Einsatzgruppen, this time under the command of Reinhard Heydrich.[182] The point of the attacks was to destroy the local Communist Party leadership and therefore the state, including "Jews in the Party and State employment", and any "radical elements".[lower-alpha 16] Cesarani writes that the killing of Jews was at this point a "subset" of these activities.[184]

Einsatzgruppe A arrived in the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) with Army Group North; Einsatzgruppe B in Belarus with Army Group Center; Einsatzgruppe C in the Ukraine with Army Group South; and Einsatzgruppe D went further south into Ukraine with the 11th Army.[185] Each Einsatzgruppe numbered around 600–1,000 men, with a few women in administrative roles.[186] Travelling with nine German Order Police battalions and three units of the Waffen-SS,[187] the Einsatzgruppen and their local collaborators had murdered almost 500,000 people by the winter of 1941–1942. By the end of the war, they had killed around two million, including about 1.3 million Jews and up to a quarter of a million Roma.[188] According to Wolfram Wette, the Germany army took part in these shootings as bystanders, photographers and active shooters; to justify their troops' involvement, army commanders would describe the victims as "hostages", "bandits" and "partisans".[189] Local populations helped by identifying and rounding up Jews, and by actively participating in the killing. In Lithuania, Latvia and western Ukraine, locals were deeply involved; Latvian and Lithuanian units participated in the murder of Jews in Belarus, and in the south, Ukrainians killed about 24,000 Jews. Some Ukrainians went to Poland to serve as guards in the camps.[190]

Toward the Holocaust

Typically, victims would undress and give up their valuables before lining up beside a ditch to be shot, or they would be forced to climb into the ditch, lie on a lower layer of corpses, and wait to be killed.[192] The latter was known as Sardinenpackung ("packing sardines"), a method reportedly started by SS officer Friedrich Jeckeln.[193]

At first the Einsatzgruppen targeted the male Jewish intelligentsia, defined as male Jews aged 15–60 who had worked for the state and in certain professions (the commandos would describe them as "Bolshevist functionaries" and similar), but from August 1941 they began to murder women and children too.[194] Christopher Browning reports that on 1 August, the SS Cavalry Brigade passed an order to its units: "Explicit order by RF-SS [Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer-SS]. All Jews must be shot. Drive the female Jews into the swamps."[195] In a speech on 6 October 1943 to party leaders, Heinrich Himmler said he had ordered that women and children be shot, but Peter Longerich and Christian Gerlach write that the murder of women and children began at different times in different areas, suggesting local influence.[196]

Notable massacres include the July 1941 Ponary massacre near Vilnius (Soviet Lithuania), in which Einsatgruppe B and Lithuanian collaborators shot 72,000 Jews and 8,000 non-Jewish Lithuanians and Poles.[197] In the Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre (Soviet Ukraine), nearly 24,000 Jews were killed between 27 and 30 August 1941.[181] The largest massacre was at a ravine called Babi Yar outside Kiev (also Soviet Ukraine), where 33,771 Jews were killed on 29–30 September 1941.[198] Einsatzgruppe C and the Order Police, assisted by Ukrainian militia, carried out the killings,[199] while the German 6th Army helped round up and transport the victims to be shot.[200] The Germans continued to use the ravine for mass killings throughout the war; the total killed there could be as high as 100,000.[201]

Historians agree that there was a "gradual radicalization" between the spring and autumn of 1941 of what Longerich calls Germany's Judenpolitik, but they disagree about whether a decision—Führerentscheidung (Führer's decision)—to murder the European Jews was made at this point.[202][lower-alpha 17] According to Christopher Browning, writing in 2004, most historians maintain that there was no order before the invasion to kill all the Soviet Jews.[204] Longerich wrote in 2010 that the gradual increase in brutality and numbers killed between July and September 1941 suggests there was "no particular order"; instead it was a question of "a process of increasingly radical interpretations of orders".[205]

Germany's allies

Romania

According to Dan Stone, the murder of Jews in Romania was "essentially an independent undertaking".[206] Romania implemented anti-Jewish measures in May and June 1940 as part of its efforts towards an alliance with Germany. Jews were forced from government service, pogroms were carried out, and by March 1941 all Jews had lost their jobs and had their property confiscated.[207] In June 1941 Romania joined Germany in its invasion of the Soviet Union.

Thousands of Jews were killed in January and June 1941 in the Bucharest pogrom and Iaşi pogrom.[208] According to a 2004 report by Tuvia Friling and others, up to 14,850 Jews died during the Iaşi pogrom.[209] The Romanian military killed up to 25,000 Jews during the Odessa massacre between 18 October 1941 and March 1942, assisted by gendarmes and the police.[210] Mihai Antonescu, Romania's deputy prime minister, was reported to have said it was "the most favorable moment in our history" to solve the "Jewish problem".[211] In July 1941 he said it was time for "total ethnic purification, for a revision of national life, and for purging our race of all those elements which are foreign to its soul, which have grown like mistletoes and darken our future".[212] Romania set up concentration camps under its control in Transnistria, reportedly extremely brutal, where 154,000–170,000 Jews were deported from 1941 to 1943.[213]

Bulgaria, Slovakia, Hungary

Bulgaria introduced anti-Jewish measures between 1940 and 1943, which included a curfew, the requirement to wear a yellow star, restrictions on owning telephones or radios, the banning of mixed marriages (except for Jews who had converted to Christianity), and the registration of property.[214] It annexed Thrace and Macedonia, and in February 1943 agreed to a demand from Germany that it deport 20,000 Jews to the Treblinka extermination camp. All 11,000 Jews from the annexed territories were sent to their deaths, and plans were made to deport an additional 6,000–8,000 Bulgarian Jews from Sofia to meet the quota.[215] When the plans became public, the Orthodox Church and many Bulgarians protested, and King Boris III canceled the deportation of Jews native to Bulgaria.[216] Instead, they were expelled to provincial areas of the country.[215]

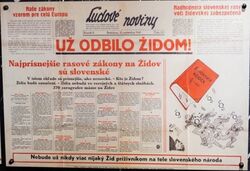

Stone writes that Slovakia, led by Roman Catholic priest Jozef Tiso (president of the Slovak State, 1939–1945), was "one of the most loyal of the collaborationist regimes". It deported 7,500 Jews in 1938 on its own initiative; introduced anti-Jewish measures in 1940; and by the autumn of 1942 had deported around 60,000 Jews to ghettos and concentration camps in Poland. Another 2,396 were deported and 2,257 killed that autumn during an uprising, and 13,500 were deported between October 1944 and March 1945.[217] According to Stone, "the Holocaust in Slovakia was far more than a German project, even if it was carried out in the context of a 'puppet' state."[218]

Although Hungary expelled Jews who were not citizens from its newly annexed lands in 1941, it did not deport most of its Jews[219] until the German invasion of Hungary in March 1944. Between 15 May and early July 1944, 437,000 Jews were deported from Hungary, mostly to Auschwitz, where most of them were gassed; there were four transports a day, each carrying 3,000 people.[220] In Budapest in October and November 1944, the Hungarian Arrow Cross forced 50,000 Jews to march to the Austrian border as part of a deal with Germany to supply forced labor. So many died that the marches were stopped.[221]

Italy, Finland, Japan

Italy introduced some antisemitic measures, but there was less antisemitism there than in Germany, and Italian-occupied countries were generally safer for Jews than those occupied by Germany. There were no deportations of Italian Jews to Germany while Italy remained an ally. In some areas, the Italian authorities even tried to protect Jews, such as in the Croatian areas of the Balkans. But while Italian forces in Russia were not as vicious towards Jews as the Germans, they did not try to stop German atrocities either.[222] Several forced labor camps for Jews were established in Italian-controlled Libya; almost 2,600 Libyan Jews were sent to camps, where 562 died.[223] In Finland, the government was pressured in 1942 to hand over its 150–200 non-Finnish Jews to Germany. After opposition from both the government and public, eight non-Finnish Jews were deported in late 1942; only one survived the war.[224] Japan had little antisemitism in its society and did not persecute Jews in most of the territories it controlled. Jews in Shanghai were confined, but despite German pressure they were not killed.[225]

Concentration and labor camps

Germany first used concentration camps as places of terror and unlawful incarceration of political opponents.[227] Large numbers of Jews were not sent there until after Kristallnacht in November 1938.[228] After war broke out in 1939, new camps were established, many outside Germany in occupied Europe.[229] Most wartime prisoners of the camps were not Germans but belonged to countries under German occupation.[230]

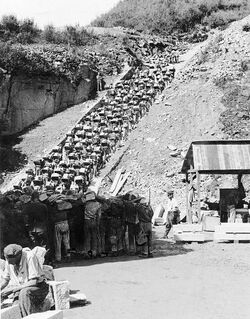

After 1942, the economic function of the camps, previously secondary to their penal and terror functions, came to the fore. Forced labor of camp prisoners became commonplace.[228] The guards became much more brutal, and the death rate increased as the guards not only beat and starved prisoners, but killed them more frequently.[230] Vernichtung durch Arbeit ("extermination through labor") was a policy; camp inmates would literally be worked to death, or to physical exhaustion, at which point they would be gassed or shot.[231] The Germans estimated the average prisoner's lifespan in a concentration camp at three months, as a result of lack of food and clothing, constant epidemics, and frequent punishments for the most minor transgressions.[232] The shifts were long and often involved exposure to dangerous materials.[233]

Transportation to and between camps was often carried out in closed freight cars with littie air or water, long delays and prisoners packed tightly.[234] In mid-1942 work camps began requiring newly arrived prisoners to be placed in quarantine for four weeks.[235] Prisoners wore colored triangles on their uniforms, the color denoting the reason for their incarceration. Red signified a political prisoner, Jehovah's Witnesses had purple triangles, "asocials" and criminals wore black and green, and gay men wore pink.[236] Jews wore two yellow triangles, one over another to form a six-pointed star.[237] Prisoners in Auschwitz were tattooed on arrival with an identification number.[238]

Final Solution

Pearl Harbor, Germany declares war on America

On 7 December 1941, Japanese aircraft attacked Pearl Harbor, an American naval base in Honolulu, Hawaii, killing 2,403 Americans. The following day, the United States declared war on Japan, and on 11 December, Germany declared war on the United States.[239] According to Deborah Dwork and Robert Jan van Pelt, Hitler had trusted American Jews, whom he assumed were all powerful, to keep the United States out of the war in the interests of German Jews. When America declared war, he blamed the Jews.[240]

Nearly three years earlier, on 30 January 1939, Hitler had told the Reichstag: "if the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will be not the Bolshevising of the earth, and thus a victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!"[241] In the view of Christian Gerlach, Hitler "announced his decision in principle" to annihilate the Jews on or around 12 December 1941, one day after his declaration of war. On that day, Hitler gave a speech in his private apartment at the Reich Chancellery to senior Nazi Party leaders: the Reichsleiter, the most senior, and the Gauleiter, the regional leaders.[242] The following day, Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, noted in his diary:

Regarding the Jewish question, the Führer is determined to clear the table. He warned the Jews that if they were to cause another world war, it would lead to their destruction. Those were not empty words. Now the world war has come. The destruction of the Jews must be its necessary consequence. We cannot be sentimental about it.[lower-alpha 20]

Christopher Browning argues that Hitler gave no order during the Reich Chancellery meeting but did make clear that he had intended his 1939 warning to the Jews to be taken literally, and he signaled to party leaders that they could give appropriate orders to others.[244] Peter Longerich interprets Hitler's speech to the party leaders as an appeal to radicalize a policy that was already being executed.[245] According to Gerlach, an unidentified former German Sicherheitsdienst officer wrote in a report in 1944, after defecting to Switzerland: "After America entered the war, the annihilation (Ausrottung) of all European Jews was initiated on the Führer's order."[246]

Four days after Hitler's meeting with party leaders, Hans Frank, Governor-General of the General Government area of occupied Poland, who was at the meeting, spoke to district governors: "We must put an end to the Jews ... I will in principle proceed only on the assumption that they will disappear. They must go."[247][lower-alpha 21] On 18 December Hitler and Himmler held a meeting to which Himmler referred in his appointment book as "Juden frage | als Partisanen auszurotten" ("Jewish question / to be exterminated as partisans"). Browning interprets this as a meeting to discuss how to justify and speak about the killing.[249]

Wannsee Conference

SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Head Office (RSHA), convened what became known as the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942 at Am Großen Wannsee 56–58, a villa in Berlin's Wannsee suburb.[250][251] The meeting had been scheduled for 9 December 1941, and invitations had been sent on 29 November, but it had been postponed indefinitely. A month later, invitations were sent out again, this time for 20 January.[252]

The 15 men present at Wannsee included Adolf Eichmann (head of Jewish affairs for the RSHA), Heinrich Müller (head of the Gestapo), and other SS and party leaders and department heads.[lower-alpha 23] Browning writes that eight of the 15 had doctorates: "Thus it was not a dimwitted crowd unable to grasp what was going to be said to them."[254] Thirty copies of the minutes, known as the Wannsee Protocol, were made. Copy no. 16 was found by American prosecutors in March 1947 in a German Foreign Office folder.[255] Written by Eichmann and stamped "Top Secret", the minutes were written in "euphemistic language" on Heydrich's instructions, according to Eichmann's later testimony.[245]

Discussing plans for a "final solution to the Jewish question" ("Endlösung der Judenfrage"), and a "final solution to the Jewish question in Europe" ("Endlösung der europäischen Judenfrage"),[250] the conference was held to share information and responsibility, coordinate efforts and policies ("Parallelisierung der Linienführung"), and ensure that authority rested with Heydrich. There was also discussion about whether to include the German Mischlinge (half-Jews).[256] Heydrich told the meeting: "Another possible solution of the problem has now taken the place of emigration, i.e. the evacuation of the Jews to the East, provided that the Fuehrer gives the appropriate approval in advance."[250] He continued:

Under proper guidance, in the course of the Final Solution, the Jews are to be allocated for appropriate labor in the East. Able-bodied Jews, separated according to sex, will be taken in large work columns to these areas for work on roads, in the course of which action doubtless a large portion will be eliminated by natural causes.

The possible final remnant will, since it will undoubtedly consist of the most resistant portion, have to be treated accordingly because it is the product of natural selection and would, if released, act as the seed of a new Jewish revival. (See the experience of history.)

In the course of the practical execution of the Final Solution, Europe will be combed through from west to east. Germany proper, including the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, will have to be handled first due to the housing problem and additional social and political necessities.

The evacuated Jews will first be sent, group by group, to so-called transit ghettos, from which they will be transported to the East.[250]

These evacuations were regarded as provisional or "temporary solutions" ("Ausweichmöglichkeiten").[257][lower-alpha 24] The final solution would encompass the 11 million Jews living not only in territories controlled by Germany, but elsewhere in Europe and adjacent territories, such as Britain, Ireland, Switzerland, Turkey, Sweden, Portugal, Spain, and Hungary, "dependent on military developments".[257] There was little doubt what the final solution was, writes Longerich: "the Jews were to be annihilated by a combination of forced labour and mass murder."[259]

Extermination camps

At the end of 1941 in occupied Poland, the Germans began building additional camps or expanding existing ones. Auschwitz, for example, was expanded in October 1941 by building Auschwitz II-Birkenau a few kilometers away.[4] By the spring or summer of 1942, gas chambers had been installed in these new facilities, except for Chełmno, which used gas vans.

| Camp | Location (occupied Poland) |

Deaths | Gas chambers |

Gas vans |

Construction began |

Mass gassing began |

Source (Yad Vashem) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auschwitz II | Brzezinka | 1,082,000 (all Auschwitz camps; includes 960,000 Jews)[lower-alpha 25] |

4[lower-alpha 26] | October 1941 (built as POW camp)[263] |

c. 20 March 1942[264][lower-alpha 27] | [265] | |

| Bełżec | Bełżec | 600,000[266] | 1 November 1941[267] | 17 March 1942[267] | [266] | ||

| Chełmno | Chełmno nad Nerem | 320,000[268] | 8 December 1941[269] | [268] | |||

| Majdanek | Lublin | 78,000Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 7 October 1941 (built as POW camp)Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". |

October 1942Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | [270] | ||

| Sobibór | Sobibór | 250,000[271] | February 1942Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | May 1942Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | [271] | ||

| Treblinka | Treblinka | 870,000[272] | May 1942[273] | 23 July 1942[273] | [272] | ||

| Total | 3,218,000 |

Other camps sometimes described as extermination camps include Maly Trostinets near Minsk in the occupied Soviet Union, where 65,000 are thought to have died, mostly by shooting but also in gas vans;[274] Mauthausen in Austria;Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Stutthof, near Gdańsk, Poland;Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and Sachsenhausen and Ravensbrück in Germany. The camps in Austria, Germany and Poland all had gas chambers to kill inmates deemed unable to work.[275]

Gas vans

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Chełmno, with gas vans only, had its roots in the Aktion T4 euthanasia program.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". In December 1939 and January 1940, gas vans equipped with gas cylinders and a sealed compartment had been used to kill the handicapped in occupied Poland.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". As the mass shootings continued in Russia, Himmler and his subordinates in the field feared that the murders were causing psychological problems for the SS,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and began searching for more efficient methods. In December 1941, similar vans, using exhaust fumes rather than bottled gas, were introduced into the camp at Chełmno,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Victims were asphyxiated while being driven to prepared burial pits in the nearby forests.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". The vans were also used in the occupied Soviet Union, for example in smaller clearing actions in the Minsk ghetto,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and in Yugoslavia.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Apparently, as with the mass shootings, the vans caused emotional problems for the operators, and the small number of victims the vans could handle made them ineffective.[276]

Gas chambers

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Christian Gerlach writes that over three million Jews were murdered in 1942, the year that "marked the peak" of the mass murder.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". At least 1.4 million of these were in the General Government area of Poland.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Victims usually arrived at the extermination camps by freight train.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Almost all arrivals at Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka were sent directly to the gas chambers,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". with individuals occasionally selected to replace dead workers.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". At Auschwitz, about 20 percent of Jews were selected to work.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Those selected for death at all camps were told to undress and hand their valuables to camp workers.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". They were then herded naked into the gas chambers. To prevent panic, they were told the gas chambers were showers or delousing chambers.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

At Auschwitz, after the chambers were filled, the doors were shut and pellets of Zyklon-B were dropped into the chambers through vents,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". releasing toxic prussic acid.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Those inside died within 20 minutes; the speed of death depended on how close the inmate was standing to a gas vent, according to the commandant Rudolf Höss, who estimated that about one-third of the victims died immediately.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Johann Kremer, an SS doctor who oversaw the gassings, testified that: "Shouting and screaming of the victims could be heard through the opening and it was clear that they fought for their lives."Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". The gas was then pumped out, and the Sonderkommando—work groups of mostly Jewish prisoners—carried out the bodies, extracted gold fillings, cut off women's hair, and removed jewellery, artificial limbs and glasses.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". At Auschwitz, the bodies were at first buried in deep pits and covered with lime, but between September and November 1942, on the orders of Himmler, 100,000 bodies were dug up and burned. In early 1943, new gas chambers and crematoria were built to accommodate the numbers.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka became known as the Operation Reinhard camps, named after the German plan to murder the Jews in the General Government area of occupied Poland.[277] Between March 1942 and November 1943, around 1,526,500 Jews were gassed in these three camps in gas chambers using carbon monoxide from the exhaust fumes of stationary diesel engines.[4] Gold fillings were pulled from the corpses before burial, but unlike in Auschwitz the women's hair was cut before death. At Treblinka, to calm the victims, the arrival platform was made to look like a train station, complete with fake clock.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Most of the victims at these three camps were buried in pits at first. From mid-1942, as part of Sonderaktion 1005, prisoners at Auschwitz, Chelmno, Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka were forced to exhume and burn bodies that had been buried, in part to hide the evidence, and in part because of the terrible smell pervading the camps and a fear that the drinking water would become polluted.[278] The corpses—700,000 in Treblinka—were burned on wood in open fire pits and the remaining bones crushed into powder.[279]

Jewish resistance

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". There was almost no resistance in the ghettos in Poland until the end of 1942.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Raul Hilberg accounted for this by evoking the history of Jewish persecution: compliance might avoid inflaming the situation until the onslaught abated.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Timothy Snyder noted that it was only during the three months after the deportations of July–September 1942 that agreement on the need for armed resistance was reached.[280]

Several resistance groups were formed, such as the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) and Jewish Military Union (ŻZW) in the Warsaw Ghetto and the United Partisan Organization in Vilna.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Over 100 revolts and uprisings occurred in at least 19 ghettos and elsewhere in Eastern Europe. The best known is the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April 1943, when the Germans arrived to send the remaining inhabitants to extermination camps. Forced to retreat on 19 April from the ŻOB and ŻZW fighters, they returned later that day under the command of SS General Jürgen Stroop (author of the Stroop Report about the uprising).Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Around 1,000 poorly armed fighters held the SS at bay for four weeks.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Polish and Jewish accounts stated that hundreds or thousands of Germans had been killed,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". while the Germans reported 16 dead.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". The Germans said that 14,000 Jews had been killed—7000 during the fighting and 7000 sent to TreblinkaLua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".—and between 53,000Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and 56,000 deported.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". According to Gwardia Ludowa, a Polish resistance newspaper, in May 1943:

From behind the screen of smoke and fire, in which the ranks of fighting Jewish partisans are dying, the legend of the exceptional fighting qualities of the Germans is being undermined. ... The fighting Jews have won for us what is most important: the truth about the weakness of the Germans."Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

During a revolt in Treblinka on 2 August 1943, inmates killed five or six guards and set fire to camp buildings; several managed to escape.[281] In the Białystok Ghetto on 16 August, Jewish insurgents fought for five days when the Germans announced mass deportations.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". On 14 October, Jewish prisoners in Sobibór attempted an escape, killing 11 SS officers, as well as two or three Ukrainian and Volksdeutsche guards. According to Yitzhak Arad, this was the highest number of SS officers killed in a single revolt.[282] Around 300 inmates escaped (out of 600 in the main camp), but 100 were recaptured and shot.[283] On 7 October 1944, 300 Jewish members, mostly Greek or Hungarian, of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz learned they were about to be killed, and staged an uprising, blowing up crematorium IV.[284] Three SS officers were killed.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". The Sonderkommando at crematorium II threw their Oberkapo into an oven when they heard the commotion, believing that a camp uprising had begun.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". By the time the SS had regained control, 451 members of the Sonderkommando were dead; 212 survived.[285]

Estimates of Jewish participation in partisan units throughout Europe range from 20,000 to 100,000.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". In the occupied Polish and Soviet territories, thousands of Jews fled into the swamps or forests and joined the partisans,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". although the partisan movements did not always welcome them.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 joined the Soviet partisan movement.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". One of the famous Jewish groups was the Bielski partisans in Belarus, led by the Bielski brothers.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Jews also joined Polish forces, including the Home Army. According to Timothy Snyder, "more Jews fought in the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944 than in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 1943."Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".[lower-alpha 28]

Polish resistance, flow of information about the mass murder

The Polish government-in-exile in London learned about Auschwitz from the Polish leadership in Warsaw, who from late 1940 "received a continual flow of information" about the camp, according to historian Michael Fleming.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". This was in large measure thanks to Captain Witold Pilecki of the Polish Home Army, who allowed himself to be arrested in September 1940 and sent there. An inmate until he escaped in April 1943, his mission was to set up a resistance movement (ZOW), prepare to take over the camp, and smuggle out information about it.[287]

On 6 January 1942, the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vyacheslav Molotov, sent out diplomatic notes about German atrocities. The notes were based on reports about mass graves and bodies surfacing from pits and quarries in areas the Red Army had liberated, as well as witness reports from German-occupied areas.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". The following month, Szlama Ber Winer escaped from the Chełmno concentration camp in Poland and passed information about it to the Oneg Shabbat group in the Warsaw Ghetto. His report, known by his pseudonym as the Grojanowski Report, had reached London by June 1942.[268][288] Also in 1942, Jan Karski sent information to the Allies after being smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto twice.[289] By late July or early August 1942, Polish leaders in Warsaw had learned about the mass killing of Jews in Auschwitz, according to Fleming.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".[lower-alpha 29] The Polish Interior Ministry prepared a report, Sprawozdanie 6/42,[290] which said at the end:

There are different methods of execution. People are shot by firing squads, killed by an "air hammer" /Hammerluft/, and poisoned by gas in special gas chambers. Prisoners condemned to death by the Gestapo are murdered by the first two methods. The third method, the gas chamber, is employed for those who are ill or incapable of work and those who have been brought in transports especially for the purpose /Soviet prisoners of war, and, recently Jews/.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

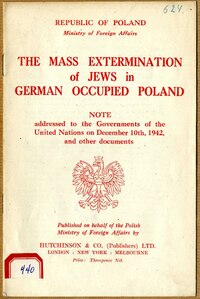

Sprawozdanie 6/42 was sent to Polish officials in London by courier and had reached them by 12 November 1942, where it was translated into English and added to another, "Report on Conditions in Poland", dated 27 November. Fleming writes that the latter was sent to the Polish Embassy in the United States.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". On 10 December 1942, the Polish Foreign Affairs Minister, Edward Raczyński, addressed the fledgling United Nations on the killings; the address was distributed with the title The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland. He told them about the use of poison gas; about Treblinka, Bełżec and Sobibór; that the Polish underground had referred to them as extermination camps; and that tens of thousands of Jews had been killed in Bełżec in March and April 1942.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". One in three Jews in Poland were already dead, he estimated, from a population of 3,130,000.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Raczyński's address was covered by the New York Times and The Times of London. Winston Churchill received it, and Anthony Eden presented it to the British cabinet. On 17 December 1942, 11 Allies issued the Joint Declaration by Members of the United Nations condemning the "bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination".[291][292]

The British and American governments were reluctant to publicize the intelligence they had received. A BBC Hungarian Service memo, written by Carlile Macartney, a BBC broadcaster and senior Foreign Office adviser on Hungary, stated in 1942: "We shouldn't mention the Jews at all." The British government's view was that the Hungarian people's antisemitism would make them distrust the Allies if their broadcasts focused on the Jews.[293] The US government similarly feared turning the war into one about the Jews; antisemitism and isolationism were common in the US before its entry into the war.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Although governments and the German public appear to have understood what was happening, it seems the Jews themselves did not. According to Saul Friedländer, "[t]estimonies left by Jews from all over occupied Europe indicate that, in contradistinction to vast segments of surrounding society, the victims did not understand what was ultimately in store for them." In Western Europe, he writes, Jewish communities seem to have failed to piece the information together, while in Eastern Europe, they could not accept that the stories they had heard from elsewhere would end up applying to them too.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

Climax, Holocaust in Hungary

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". The SS liquidated most of the Jewish ghettos of the General Government area of Poland in 1942–1943 and shipped their populations to the camps for extermination.[294] The only exception was the Lodz Ghetto, which was not liquidated until mid-1944.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". About 42,000 Jews in the General Government were shot during Operation Harvest Festival (Aktion Erntefest) on 3–4 November 1943.[295] At the same time, rail shipments were arriving regularly from western and southern Europe at the extermination camps.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Shipments of Jews to the camps had priority on the German railways over anything but the army's needs, and continued even in the face of the increasingly dire military situation at the end of 1942.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Army leaders and economic managers complained about this diversion of resources and the killing of skilled Jewish workers,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". but Nazi leaders rated ideological imperatives above economic considerations.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".