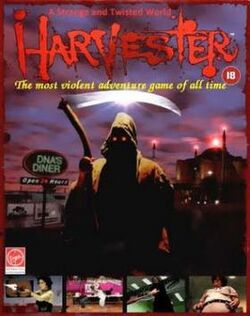

Harvester (video game)

Topic: Software

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

| Harvester | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | DigiFX Interactive |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Producer(s) | Lee Jacobson |

| Designer(s) | Gilbert P. Austin |

| Platform(s) | DOS, Microsoft Windows, Linux |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Interactive film, point-and-click adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Harvester is a 1996 point-and-click adventure game written and directed by Gilbert P. Austin, known for its violent content, cult following, and examination of violence.[2] Players take on the role of Steve Mason, an eighteen-year-old man who awakens in a Midwestern town in 1953 with no memory of who he is and a vague sense he does not belong there. Over the course of the next week, he is coerced or manipulated into performing a series of seemingly mundane tasks with increasingly violent consequences at the behest of "The Order of the Harvest Moon," a cult-like organization which seems to dominate the town and which promises to reveal the truth about Steve and his presence in Harvest.

Plot

Teenager Steve Mason awakens in the small American farming town of Harvest in the year 1953, with no memories of his past or who he is. Exploring his home, he discovers that he doesn't recognize his mother or younger brother, both of whom act strangely—his mother seemingly can't stop baking dozens of cookies for a charity event a week away, causing her to throw out each subsequent batch; and his brother obsessively watches an ultra-violent cowboy show that seems to be the only program broadcast on Harvest televisions.

Exploring the town, Steve discovers Harvest is populated by hostile, strange individuals whom he likens to facsimiles or parodies of real people. Steve further learns that no one believes him to genuinely be amnesiac, with every citizen he meets responding to his pleas for help with the canned response "You always were a kidder, Steve." Everyone in town further encourages Steve to join the Lodge, a large building (reminiscent of the Hagia Sophia) located at the center of town that serves as the headquarters of the Order of the Harvest Moon, which seems to be the sociopolitical center of life in Harvest.

Learning that he's set to be married in two weeks, Steve goes to meet his supposed fiancée, Stephanie Pottsdam, the daughter of Mr. Pottsdam, an unemployed man who hopes to get a job alongside Steve's father working in Harvest's meat packing plant and who openly expresses his lust for his own daughter. Meeting Stephanie, Steve finds that she, too, has amnesia, and woke up the same morning as him with no idea of how she got to Harvest. The two form an alliance to figure out their past and escape the town.

Steve visits the Sergeant at Arms at the Lodge, who tells him that all of his questions will be answered inside the building, and sets about giving him a series of tasks that serve as initiation rites. Over the course of the next week, Steve is given a new "task" each day, beginning with petty acts of vandalism that quickly escalate to theft and arson, with each task having unforeseen, tragic circumstances that usually result in someone's accidental death, murder, or suicide. Meanwhile, driven by their mutual fear and reliance on one another, Steve and Stephanie become lovers.

On the final day of his initiation, Steve discovers a mutilated skull and spinal cord in Stephanie's bed, which the Sergeant at Arms tells him is his invitation to the Lodge. Venturing inside, Steve discovers that the Lodge is composed of a series of rooms called "Temples" which serve as mordant burlesques of real civic locations (including a living room with a dead family and a kitchen where a chef prepares human meat) and whose inhabitants challenge him with a series of puzzles ostensibly meant to teach lessons integral to understanding the precepts of the lodge. Each "lesson" turns out to be an inversion of traditional morality, including the futility of charity, the uselessness of the elderly, and the benefits of lust and vanity.

At the highest level of the Lodge, the Sergeant at Arms presents a still-living Stephanie and explains that Harvest is an elaborate virtual reality simulator being operated by a group of scientists in the 1990s to determine if it's possible to turn average humans into serial killers. Steve and Stephanie are the only real people in the simulation, and everything Steve has experienced has been intended to warp his reality and break down his inhibitions to prepare him for life as a serial killer. The Sergeant offers him two options: murder Stephanie, committing his first real crime and accepting a future as a murderer, or refuse, in which case the scientists will render both Steve and Stephanie brain dead in the laboratory. Should Steve choose the second option, the Sergeant informs him he and Stephanie will live an entire lifetime of happiness in the Harvest simulator in the seconds before their death.

If the player chooses to kill Stephanie, Steve beats Stephanie to death and then removes her skull and spinal cord. After the murder is complete, Steve awakens within the virtual reality simulator. Hitchhiking home, he brutally murders the driver who picks him up. Steve returns home, where his mother criticizes him for playing violent video games, telling him that people who consume violent media go on to commit violent acts in real life. Steve laughs in response as the camera enters his throat and stomach, revealing dissolving body parts of the driver he killed earlier.

If the player chooses to spare Stephanie, the Sergeant at Arms performs an impromptu wedding in the chapel before letting the pair go. Steve and Stephanie buy a home, have a child, and grow old together before dying peacefully and being buried in the Harvest cemetery. In real life, the scientists express disappointment at the results of their experiment as they look on at the pair's dead bodies.

Cast

- Kurt Kistler as Steve Mason

- Ryan Wickerham as the voice of Steve

- Lisa Cangelosi as Stephanie

- Kevin Obregon as Sergeant at Arms / Technician #1

- Ryan Wickerham as the voice of Sergeant at Arms

- Mary Allen as Mom / Mrs. Pottsdam / Generic PTA Moms

- Gilbert P. Austin as Mr. Moynahan

- Nelson Knight as Sheriff Dwayne

- Bob Cawley as Mr. Johnson

- Graham Teschke as Col. Buster Monroe

- Tracy Odell as Dark Exotic Woman (as Tracy Napodano)

- Mike Napodano as Cue Card Man / Technician #2

- Michael Napodano Jr. as Baby Sister

- Tim Higgins as Chessmaster

- Rheagan Wallace as Karin

- Roxanne Lovseth as Edna Fitzpatrick

- Travis Miller as Mr. Pottsdam

- Tom Lima as Kewpie

- Christopher Ammons as Jimmy James

- Charles Beecham as Postmaster Boyle

- Jack Irons as Grand Poobah

- Persis Forster as Tetsua Crumb (Wasp Lady)

Gameplay

The game utilizes a point and click interface. Players must visit various locations within the game's fictional town of Harvest via an overhead map. By speaking to various townspeople and clicking on special "hotspots", players can learn information and collect items that progress the game's story and play. Harvester also features a fighting system where players can attack other characters by selecting a weapon and then clicking on the target. Both the target and the player's character have a limited amount of health available, allowing for either the player or the target to die. Players can choose to progress through the game by solving puzzles or by killing one of the non-playable characters.

Development and controversy

Harvester was developed by FutureVision (renamed DigiFX by the time of the game's release). Writer/director Gilbert P. Austin recounted:

My feeling was that FutureVision, being a small company, would need something “high concept” to compete with the industry giants of the time, and I argued that Harvester was exactly that idea. It was really the only idea that I pitched. I remember that it came to me in a flash. That’s how I get a lot of my ideas, in creative rushes where I can barely write fast enough to get it all down. ... The concept of Harvester, the idea that at the end of the game I wanted the player to mull over whether he had internalized the over-the-top violence and surreal imagery of the game in the same manner that Steve had, and the primary ending…all this was in the initial concept that I jotted down in one of those small reporter spiral notepads in about 30 minutes. That’s what I pitched to FutureVision, and they bought it.[3]

Harvester was first announced to the public at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in January 1994 in Las Vegas.[3] The video footage was filmed in the back warehouse of publisher Merit Software.[3] Though he was only contracted as the game's writer, Austin voluntarily directed the filming to ensure it stayed true to his vision for the game.[3] Austin finished the creative work in Autumn 1994 and moved on to other projects, leaving producer Lee Jacobson in sole charge of the remaining development.[3] The game was set to be released the same year but the programming took two years to finish, and it became a commercial failure.[3]

In a December 1996 press conference, family psychologist Dr. David Walsh released a list of excessively violent games. Jacobson publicly demanded that Harvester, which was not included in Dr. Walsh's list, be added to it.[4] Gaming journalist Christian Svensson described Jacobson's actions as "shameless", and did not refer to Jacobson, DigiFX, or Harvester by name so as not to provide positive reinforcement for publicity seeking.[5]

In Germany, the game was banned.[6]

The game was designed by DigiFX Interactive and published by Merit Studios in 1996.[7] On March 6, 2014, Lee Jacobson re-released it on GOG.com,[8] for PC and Mac. On April 4, 2014, Nightdive Studios re-released it on Steam for PC and Linux.[9]

ZOOM-Platform.com would release their version, alongside other Lee Jacobson exclusives, such as Command Adventures: Starship and The Fortress of Dr. Radiaki, for Windows, Mac and Linux on January 27, 2023.[10]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Harvester received "mixed or average" reviews, according to review aggregator Metacritic.[11] PC Gamer gave Harvester a positive review upon its initial release,[15] but panned it in a 2011 review where they called it the "goriest, most confusing, and above all stupidest horror game ever."[17] Allgame remarked that the game's delayed release negatively impacted its reception, as the game felt dated when it was finally released. They felt that this was indicative of the game as a whole, as "conversations with characters are frustrating and often make little sense, plus the manner in which the plot develops is disappointing. ... there are things that are never explained, and the final third of the game is dull and pointless."[13] GameSpot's review was mixed, as they felt that there was "nothing actually revolutionary going on in Harvester" but praised the game's full-motion video segments as "truly disturbing" and commented that it had "tried-and-true adventure mechanics with entertaining twists".[14]

Entertainment Weekly commented that "this gratuitously violent game doesn’t make much sense, but it is a lot of twisted fun."[16]

References

- ↑ "Online Gaming Review". 1997-02-27. http://www.ogr.com/news/news0996.html.

- ↑ Elston, Brett (30 October 2009). "The bloodiest games you've never played". Games Radar. http://www.gamesradar.com/the-bloodiest-games-youve-never-played/?page=3. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Malin, Aarno. "Inside Harvester - A Fan Interview with Gilbert P. Austin". GOG.com. http://gogcom.tumblr.com/post/92424446858/harvester-gilbert-austin-interview. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ↑ "What Is Senator Lieberman's Problem with Videogames?". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (28): 11. April 1997.

- ↑ Svensson, Christian (March 1997). "Lieberman Back in Action". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (27): 28.

- ↑ "Retro Gaming: Harvester (1996)". http://www.weirdretro.org.uk/captains-blog/retro-gaming-harvester-1996.

- ↑ Computer Gaming World, Volumes 150-153. Golden Empire Publications. 1997. https://books.google.com/books?id=6eEzAQAAIAAJ&q=%22Harvester%22+. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- ↑ GOG.com (2014-03-06). "Release: Harvester". CD Projekt. http://www.gog.com/news/release_harvester.

- ↑ Valve (2014-04-04). "Now Available on Steam - Harvester". Steam. http://store.steampowered.com/news/12875/.

- ↑ "New Titles - 2023-01-27". https://www.zoom-platform.com/news/new-titles-2023-01-27.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Harvester for PC Reviews". https://www.metacritic.com/game/harvester/critic-reviews/?platform=pc. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ↑ Indovina, Kurt (October 30, 2015). "Harvester Review". Adventure Gamers. https://adventuregamers.com/articles/view/26984. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 House, Matthew. "Harvester". Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141117033258/http://www.allgame.com/game.php?id=5634&tab=overview. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Hudak, Chris (August 29, 1996). "Harvester Review". https://www.gamespot.com/reviews/harvester-review/1900-2537444/. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gamer, PC (April 27, 2014). "Harvester review - December 1996, US edition". PC Gamer. http://www.pcgamer.com/harvester-review-december-1996-us-edition/. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Harvester" (in en). EW.com. https://ew.com/article/1996/12/20/harvester/.

- ↑ Cobbett, Richard (May 14, 2011). "Saturday Crapshoot: Harvester". PC Gamer. http://www.pcgamer.com/saturday-crapshoot-harvester/. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

Warning: Default sort key "Harvester (Video Game)" overrides earlier default sort key "Mobygames".

|

KSF

KSF