Systemd

Topic: Software

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

| |

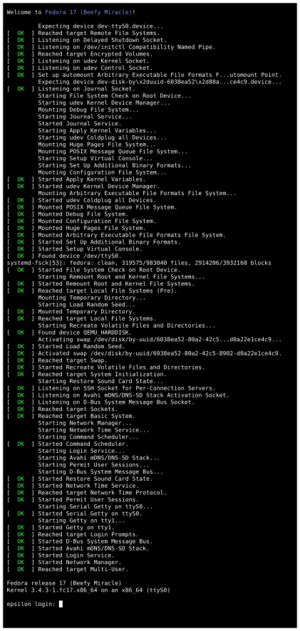

systemd startup on Fedora 17 | |

| Original author(s) | Lennart Poettering[1] |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Red Hat (Lennart Poettering, Kay Sievers, Harald Hoyer, Daniel Mack, Tom Gundersen, David Herrmann);[2] 345 different authors in 2018[3] and 2,032 different authors in total [4] |

| Initial release | 30 March 2010 |

| Stable release | 251 (May 21, 2022) [±][5] |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Linux |

| Type |

|

| License | LGPLv2.1+[6] |

| Website | systemd.io |

systemd is a software suite that provides an array of system components for Linux[7] operating systems. The main aim is to unify service configuration and behavior across Linux distributions.[8] Its primary component is a "system and service manager" – an init system used to bootstrap user space and manage user processes. It also provides replacements for various daemons and utilities, including device management, login management, network connection management, and event logging. The name systemd adheres to the Unix convention of naming daemons by appending the letter d.[9] It also plays on the term "System D", which refers to a person's ability to adapt quickly and improvise to solve problems.[10]

Since 2015, the majority of Linux distributions have adopted systemd, having replaced other init systems such as SysV init. It has been praised by developers and users of distributions that adopted it for providing a stable, fast out-of-the-box solution for issues that had existed in the Linux space for years.[11][12][13] At the time of adoption of systemd on most Linux distributions, it was the only software suite that offered reliable parallelism during boot as well as centralized management of processes, daemons, services and mount points.

Critics of systemd contend that it suffers from mission creep and bloat; the latter affecting other software (such as the GNOME desktop), adding dependencies on systemd, reducing its compatibility with other Unix-like operating systems and making it difficult for sysadmins to integrate alternative solutions. Concerns have also been raised about Red Hat and its parent company IBM controlling the scene of init systems on Linux.[14][1] Critics also contend that the complexity of systemd results in a larger attack surface, reducing the overall security of the platform.[15]

History

Lennart Poettering and Kay Sievers, the software engineers then working for Red Hat who initially developed systemd,[2] started a project to replace Linux's conventional System V init in 2010.[16] An April 2010 blog post from Poettering, titled "Rethinking PID 1", introduced an experimental version of what would later become systemd.[17] They sought to surpass the efficiency of the init daemon in several ways. They wanted to improve the software framework for expressing dependencies, to allow more processing to be done concurrently or in parallel during system booting, and to reduce the computational overhead of the shell.

In May 2011 Fedora Linux became the first major Linux distribution to enable systemd by default, replacing Upstart. The reasoning at the time was that systemd provided extensive parallelization during startup, better management of processes and overall a saner, dependency-based approach to control of the system.[18]

In October 2012, Arch Linux made systemd the default, switching from SysVinit.[19] Developers had debated since August 2012[13] and came to the conclusion that it was faster and had more features than SysVinit, and that maintaining the latter was not worth the effort in patches.[20] Some of them thought that the criticism towards the implementation of systemd was not based on actual shortcomings of the software, rather the disliking of Lennart from a part of the Linux community and the general hesitation for change. Specifically, some of the complaints regarding systemd not being programmed in bash, it being bigger and more extensive than SysVinit, the use of D-bus, and the optional on-disk format of the journal were regarded as advantages by programmers.[21]

Between October 2013 and February 2014, a long debate among the Debian Technical Committee occurred on the Debian mailing list,[22] discussing which init system to use as the default in Debian 8 "jessie", and culminating in a decision in favor of systemd. The debate was widely publicized[23][24] and in the wake of the decision the debate continues on the Debian mailing list. In February 2014, after Debian's decision was made, Mark Shuttleworth announced on his blog that Ubuntu would follow in implementing systemd, discarding its own Upstart.[25][26]

In November 2014 Debian Developer Joey Hess,[27] Debian Technical Committee members Russ Allbery[28] and Ian Jackson,[29] and systemd package-maintainer Tollef Fog Heen[30] resigned from their positions. All four justified their decision on the public Debian mailing list and in personal blogs with their exposure to extraordinary stress-levels related to ongoing disputes on systemd integration within the Debian and FOSS community that rendered regular maintenance virtually impossible.

In August 2015 systemd started providing a login shell, callable via machinectl shell.[31]

In September 2016, a security bug was discovered that allowed any unprivileged user to perform a denial-of-service attack against systemd.[32] Rich Felker, developer of musl, stated that this bug reveals a major "system development design flaw".[33] In 2017 another security bug was discovered in systemd, CVE-2017-9445, which "allows disruption of service" by a "malicious DNS server".[34][35] Later in 2017, the Pwnie Awards gave author Lennart Poettering a "lamest vendor response" award due to his handling of the vulnerabilities.[36]

Design

telephony, bootmode, dlog, and tizen service are from Tizen and are not components of systemd.[37]systemd-nspawn[38]Poettering describes systemd development as "never finished, never complete, but tracking progress of technology". In May 2014, Poettering further described systemd as unifying "pointless differences between distributions", by providing the following three general functions:[39]

- A system and service manager (manages both the system, by applying various configurations, and its services)

- A software platform (serves as a basis for developing other software)

- The glue between applications and the kernel (provides various interfaces that expose functionalities provided by the kernel)

systemd includes features like on-demand starting of daemons, snapshot support, process tracking[40] and Inhibitor Locks.[41] It is not just the name of the init daemon but also refers to the entire software bundle around it, which, in addition to the systemd init daemon, includes the daemons journald, logind and networkd, and many other low-level components. In January 2013, Poettering described systemd not as one program, but rather a large software suite that includes 69 individual binaries.[42] As an integrated software suite, systemd replaces the startup sequences and runlevels controlled by the traditional init daemon, along with the shell scripts executed under its control. systemd also integrates many other services that are common on Linux systems by handling user logins, the system console, device hotplugging (see udev), scheduled execution (replacing cron), logging, hostnames and locales.

Like the init daemon, systemd is a daemon that manages other daemons, which, including systemd itself, are background processes. systemd is the first daemon to start during booting and the last daemon to terminate during shutdown. The systemd daemon serves as the root of the user space's process tree; the first process (PID 1) has a special role on Unix systems, as it replaces the parent of a process when the original parent terminates. Therefore, the first process is particularly well suited for the purpose of monitoring daemons.

systemd executes elements of its startup sequence in parallel, which is theoretically faster than the traditional startup sequence approach.[43] For inter-process communication (IPC), systemd makes Unix domain sockets and D-Bus available to the running daemons. The state of systemd itself can also be preserved in a snapshot for future recall.

Core components and libraries

Following its integrated approach, systemd also provides replacements for various daemons and utilities, including the startup shell scripts, pm-utils, inetd, acpid, syslog, watchdog, cron and atd. systemd's core components include the following:

- systemd is a system and service manager for Linux operating systems.

- systemctl is a command to introspect and control the state of the systemd system and service manager. Not to be confused with sysctl.

- systemd-analyze may be used to determine system boot-up performance statistics and retrieve other state and tracing information from the system and service manager.

systemd tracks processes using the Linux kernel's cgroups subsystem instead of using process identifiers (PIDs); thus, daemons cannot "escape" systemd, not even by double-forking. systemd not only uses cgroups, but also augments them with systemd-nspawn and machinectl, two utility programs that facilitate the creation and management of Linux containers.[44] Since version 205, systemd also offers ControlGroupInterface, which is an API to the Linux kernel cgroups.[45] The Linux kernel cgroups are adapted to support kernfs,[46] and are being modified to support a unified hierarchy.[47]

Ancillary components

Beside its primary purpose of providing a Linux init system, the systemd suite can provide additional functionality, including the following components:

- journald

- systemd-journald is a daemon responsible for event logging, with append-only binary files serving as its logfiles. The system administrator may choose whether to log system events with systemd-journald, syslog-ng or rsyslog. The potential for corruption of the binary format has led to much heated debate.[48]

- libudev

- libudev is the standard library for utilizing udev, which allows third-party applications to query udev resources.

- localed

- logind

- systemd-logind is a daemon that manages user logins and seats in various ways. It is an integrated login manager that offers multiseat improvements[49] and replaces ConsoleKit, which is no longer maintained.[50] For X11 display managers the switch to logind requires a minimal amount of porting.[51] It was integrated in systemd version 30.

- homed

- homed is a daemon that provides portable human-user accounts that are independent of current system configuration. homed moves various pieces of data such as UID/GID from various places across the filesystem into one file,

~/.identity. homed manages the user's home directory in various ways such as a plain directory, a btrfs subvolume, a Linux Unified Key Setup volume, an fscrypt directory, or mounted from an SMB server. - networkd

- networkd is a daemon to handle the configuration of the network interfaces; in version 209, when it was first integrated, support was limited to statically assigned addresses and basic support for bridging configuration.[52][53][54][55][56] In July 2014, systemd version 215 was released, adding new features such as a DHCP server for IPv4 hosts, and VXLAN support.[57][58]

networkctlmay be used to review the state of the network links as seen by systemd-networkd.[59] Configuration of new interfaces has to be added under the /lib/systemd/network/ as a new file ending with .network extension. - resolved

- provides network name resolution to local applications

- systemd-boot

- systemd-boot is a boot manager, formerly known as gummiboot. Kay Sievers merged it into systemd with rev 220.

- systemd-bsod

- systemd-bsod is an error reporter used to generate Blue Screen of Death.

- timedated

- systemd-timedated is a daemon that can be used to control time-related settings, such as the system time, system time zone, or selection between UTC and local time-zone system clock. It is accessible through D-Bus.[60] It was integrated in systemd version 30.

- timesyncd

- is a daemon that has been added for synchronizing the system clock across the network.

- tmpfiles

- systemd-tmpfiles is a utility that takes care of creation and clean-up of temporary files and directories. It is normally run once at startup and then in specified intervals.

- udevd

- udev is a device manager for the Linux kernel, which handles the /dev directory and all user space actions when adding/removing devices, including firmware loading. In April 2012, the source tree for udev was merged into the systemd source tree.[61][62] In order to match the version number of udev, systemd maintainers bumped the version number directly from 44 to 183.[63]

- On 29 May 2014, support for firmware loading through udev was dropped from systemd, as it was decided that the kernel should be responsible for loading firmware.[64]

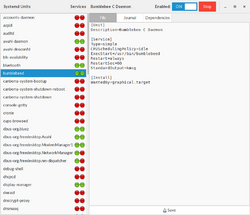

Configuration of systemd

systemd is configured exclusively via plain-text files.

systemd records initialization instructions for each daemon in a configuration file (referred to as a "unit file") that uses a declarative language, replacing the traditionally used per-daemon startup shell scripts. The syntax of the language is inspired by .ini files.[65]

Unit-file types[66] include:

- .service

- .socket

- .device (automatically initiated by systemd[67])

- .mount

- .automount

- .swap

- .target

- .path

- .timer (which can be used as a cron-like job scheduler[68])

- .snapshot

- .slice (used to group and manage processes and resources[69])

- .scope (used to group worker processes, not intended to be configured via unit files[70])

Adoption

| Linux distribution | Date added to software repository[lower-alpha 1] | Enabled by default? | Date released as default | Runs without? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine Linux | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Android | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Arch Linux | January 2012[71] | Yes | October 2012[72] | No |

| antiX Linux | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Artix Linux | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| CentOS | July 2014 | Yes | July 2014 (v7.0) | No |

| CoreOS | July 2013 | Yes | October 2013 (v94.0.0)[73][74] | No |

| Debian | April 2012[75] | Yes | April 2015 (v8.0)[76] | Jessie is the last release supporting installing without systemd.[77] In bullseye, a number of alternative init systems are supported |

| Devuan | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Fedora Linux | November 2010 (v14)[78] | Yes | May 2011 (v15) | No |

| Gentoo Linux[lower-alpha 2] | July 2011[79][81][82] | Optional[83] | N/A | Yes |

| GNU Guix System | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Knoppix | N/A | No [84][85] | N/A | Yes |

| Linux Mint | June 2016 (v18.0) | Yes | August 2018 (LMDE 3) | No [86] |

| Mageia | January 2011 (v1.0)[87] | Yes | May 2012 (v2.0)[88] | No [89] |

| Manjaro Linux | November 2013 | Yes | November 2013 | No |

| openSUSE | March 2011 (v11.4)[90] | Yes | September 2012 (v12.2)[91] | No |

| Parabola GNU/Linux-libre | January 2012[71] | Optional[92] | N/A | Yes |

| Red Hat Enterprise Linux | June 2014 (v7.0)[93] | Yes | June 2014 (v7.0) | No |

| Slackware | N/A (not in repository) | No | N/A | Yes |

| Solus | N/A | Yes | N/A | No |

| Source Mage | June 2011[94] | No | N/A | Yes |

| SUSE Linux Enterprise Server | October 2014 (v12) | Yes | October 2014 (v12) | No |

| Ubuntu | April 2013 (v13.04) | Yes | April 2015 (v15.04) | |

| Void Linux | June 2011, removed June 2015 [95] | No | N/A | Yes |

While many distributions boot systemd by default, some allow other init systems to be used; in this case switching the init system is possible by installing the appropriate packages. A fork of Debian called Devuan was developed to avoid systemd[96][97] and has reached version 4.0 for stable usage. In December 2019, the Debian project voted in favour of retaining systemd as the default init system for the distribution, but with support for "exploring alternatives".[98]

Integration with other software

In the interest of enhancing the interoperability between systemd and the GNOME desktop environment, systemd coauthor Lennart Poettering asked the GNOME Project to consider making systemd an external dependency of GNOME 3.2.[99]

In November 2012, the GNOME Project concluded that basic GNOME functionality should not rely on systemd.[100] However, GNOME 3.8 introduced a compile-time choice between the logind and ConsoleKit API, the former being provided at the time only by systemd. Ubuntu provided a separate logind binary but systemd became a de facto dependency of GNOME for most Linux distributions, in particular since ConsoleKit is no longer actively maintained and upstream recommends the use of systemd-logind instead.[101] The developers of Gentoo Linux also attempted to adapt these changes in OpenRC, but the implementation contained too many bugs, causing the distribution to mark systemd as a dependency of GNOME.[102][103]

GNOME has further integrated logind.[104] As of Mutter version 3.13.2, logind is a dependency for Wayland sessions.[105]

Reception

The design of systemd has ignited controversy within the free-software community. Critics regard systemd as overly complex and suffering from continued feature creep, arguing that its architecture violates the Unix philosophy. There is also concern that it forms a system of interlocked dependencies, thereby giving distribution maintainers little choice but to adopt systemd as more user-space software comes to depend on its components, which is similar to the problems created by PulseAudio, another project which was also developed by Lennart Poettering.[106][107]

In a 2012 interview, Slackware's lead Patrick Volkerding expressed reservations about the systemd architecture, stating his belief that its design was contrary to the Unix philosophy of interconnected utilities with narrowly defined functionalities.[108] As of August 2018[update], Slackware does not support or use systemd, but Volkerding has not ruled out the possibility of switching to it.[109]

In January 2013, Lennart Poettering attempted to address concerns about systemd in a blog post called The Biggest Myths.[42]

In February 2014, musl's Rich Felker opined that PID 1 is too special to be saddled with additional responsibilities, believing that PID 1 should only be responsible for starting the rest of the init system and reaping zombie processes, and that the additional functionality added by systemd can be provided elsewhere and unnecessarily increases the complexity and attack surface of PID 1.[110]

In March 2014 Eric S. Raymond commented that systemd's design goals were prone to mission creep and software bloat.[111] In April 2014, Linus Torvalds expressed reservations about the attitude of Kay Sievers, a key systemd developer, toward users and bug reports in regard to modifications to the Linux kernel submitted by Sievers.[112] In late April 2014 a campaign to boycott systemd was launched, with a website listing various reasons against its adoption.[113][114]

In an August 2014 article published in InfoWorld, Paul Venezia wrote about the systemd controversy and attributed the controversy to violation of the Unix philosophy, and to "enormous egos who firmly believe they can do no wrong".[115] The article also characterizes the architecture of systemd as similar to that of svchost.exe, a critical system component in Microsoft Windows with a broad functional scope.[115]

In a September 2014 ZDNet interview, prominent Linux kernel developer Theodore Ts'o expressed his opinion that the dispute over systemd's centralized design philosophy, more than technical concerns, indicates a dangerous general trend toward uniformizing the Linux ecosystem, alienating and marginalizing parts of the open-source community, and leaving little room for alternative projects. He cited similarities with the attitude he found in the GNOME project toward non-standard configurations.[116] On social media, Ts'o also later compared the attitudes of Sievers and his co-developer, Lennart Poettering, to that of GNOME's developers.[117]

Forks and alternative implementations

Forks of systemd are closely tied to critiques of it outlined in the above section. Forks generally try to improve on at least one of portability (to other libcs and Unix-like systems), modularity, or size. A few forks have collaborated under the FreeInit banner.[118]

Fork of components

eudev

In 2012, the Gentoo Linux project created a fork of udev in order to avoid dependency on the systemd architecture. The resulting fork is called eudev and it makes udev functionality available without systemd.[119] A stated goal of the project is to keep eudev independent of any Linux distribution or init system.[120] In 2021, Gentoo announced that support of eudev would cease at the beginning of 2022. An independent group of maintainers have since taken up eudev.[121]

elogind

Elogind is the systemd project's "logind", extracted to be a standalone daemon. It integrates with PAM to know the set of users that are logged into a system and whether they are logged in graphically, on the console, or remotely. Elogind exposes this information via the standard org.freedesktop.login1 D-Bus interface, as well as through the file system using systemd's standard /run/systemd layout. Elogind also provides "libelogind", which is a subset of the facilities offered by "libsystemd". There is a "libelogind.pc" pkg-config file as well.[122]

ConsoleKit2

ConsoleKit was forked in October 2014 by Xfce developers wanting its features to still be maintained and available on operating systems other than Linux. While not ruling out the possibility of reviving the original repository in the long term, the main developer considers ConsoleKit2 a temporary necessity until systembsd matures.[123]

Abandoned forks

Fork of components

LoginKit

LoginKit was an attempt to implement a logind (systemd-logind) shim, which would allow packages that depend on systemd-logind to work without dependency on a specific init system.[124] The project has been defunct since February 2015.[125]

systembsd

In 2014, a Google Summer of Code project named "systembsd" was started in order to provide alternative implementations of these APIs for OpenBSD. The original project developer began it in order to ease his transition from Linux to OpenBSD.[126] Project development finished in July 2016.[127]

The systembsd project did not provide an init replacement, but aimed to provide OpenBSD with compatible daemons for hostnamed, timedated, localed, and logind. The project did not create new systemd-like functionality, and was only meant to act as a wrapper over the native OpenBSD system. The developer aimed for systembsd to be installable as part of the ports collection, not as part of a base system, stating that "systemd and *BSD differ fundamentally in terms of philosophy and development practices."[126]

notsystemd

Notsystemd intends to implement all systemd's features working on any init system.[128] It was forked by the Parabola GNU/Linux-libre developers to build packages with their development tools without the necessity of having systemd installed to run systemd-nspawn. Development ceased in July 2018.[129]

Fork including init system

uselessd

In 2014, uselessd was created as a lightweight fork of systemd. The project sought to remove features and programs deemed unnecessary for an init system, as well as address other perceived faults.[130] Project development halted in January 2015.[131]

uselessd supported the musl and µClibc libraries, so it may have been used on embedded systems, whereas systemd only supports glibc. The uselessd project had planned further improvements on cross-platform compatibility, as well as architectural overhauls and refactoring for the Linux build in the future.[132]

InitWare

InitWare is a modular refactor of systemd, porting the system to BSD platforms without glibc or Linux-specific system calls. It is known to work on DragonFly BSD, FreeBSD, NetBSD, and GNU/Linux. Components considered unnecessary are dropped.[133]

See also

- BusyBox

- launchd

- Operating system service management

- readahead

- runit

- Service Management Facility

- GNU Daemon Shepherd

- Upstart

- svchost.exe

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Lennart Poettering on systemd's Tumultuous Ascendancy". 26 January 2017. https://thenewstack.io/unix-greatest-inspiration-behind-systemd/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 systemd README, https://cgit.freedesktop.org/systemd/systemd/tree/README, retrieved 9 September 2012

- ↑ "Systemd Hits A High Point For Number Of New Commits & Contributors During 2018 - Phoronix". https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=Systemd-EOY2018-Stats.

- ↑ Used the "contributors" statistic from: systemd/systemd, systemd, 2023-12-03, https://github.com/systemd/systemd, retrieved 2023-12-03

- ↑ "Release v251". 2022-05-21. https://github.com/systemd/systemd/releases/tag/v251.

- ↑ Poettering, Lennart (21 April 2012), systemd Status Update, https://0pointer.de/blog/projects/systemd-update-3.html, retrieved 28 April 2012

- ↑ "Rethinking PID 1". 30 April 2010. https://0pointer.de/blog/projects/systemd.html. "systemd uses many Linux-specific features, and does not limit itself to POSIX. That unlocks a lot of functionality a system that is designed for portability to other operating systems cannot provide."

- ↑ "InterfaceStabilityPromise". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/InterfaceStabilityPromise/.

- ↑ "systemd System and Service Manager". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/. "Yes, it is written systemd, not system D or System D, or even SystemD. And it isn't system d either. Why? Because it's a system daemon, and under Unix/Linux those are in lower case, and get suffixed with a lower case d."

- ↑ Poettering, Lennart; Sievers, Kay; Leemhuis, Thorsten (8 May 2012), Control Centre: The systemd Linux init system, The H, http://h-online.com/-1565543, retrieved 9 September 2012

- ↑ "Debate/initsystem/systemd - Debian Wiki". https://wiki.debian.org/Debate/initsystem/systemd.

- ↑ "F15 one page release notes - Fedora Project Wiki". https://fedoraproject.org/wiki/F15_one_page_release_notes.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Gaudreault, Stéphane (14 August 2012). "Migration to systemd". arch-dev-public (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 2021-11-15.

- ↑ Saunders, Mike (11 November 2015). "Linux 101: Get the most out of systemd". Linux Voice. https://www.linuxvoice.com/linux-101-get-the-most-out-of-systemd/.

- ↑ "Freedesktop Systemd : List of security vulnerabilities". CVE Details. https://www.cvedetails.com/vulnerability-list/vendor_id-7971/product_id-38088/Freedesktop-Systemd.html.

- ↑ Simmonds, Chris (2015). "9: Starting up - the init Program". Mastering Embedded Linux Programming. Packt Publishing Ltd. p. 239. ISBN 9781784399023. https://books.google.com/books?id=_h_lCwAAQBAJ. Retrieved 20 June 2016. "systemd defines itself as a system and service manager. The project was initiated in 2010 by Lennart Poettering and Kay Sievers to create an integrated set of tools for managing a Linux system including an init daemon."

- ↑ Lennart Poettering (30 April 2010). "Rethinking PID 1". http://0pointer.de/blog/projects/systemd.html.

- ↑ "F15 one page release notes", fedoraproject.org, 24 May 2001, https://fedoraproject.org/wiki/F15_one_page_release_notes, retrieved 24 September 2013

- ↑ "Arch Linux - News: systemd is now the default on new installations". https://archlinux.org/news/systemd-is-now-the-default-on-new-installations/.

- ↑ Groot, Jan de (14 August 2012). "Migration to systemd". arch-dev-public (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ "Archlinux is moving to systemd (Page 2) / Arch Discussion / Arch Linux Forums". https://bbs.archlinux.org/viewtopic.php?pid=1149530#p1149530.

- ↑ "#727708 - tech-ctte: Decide which init system to default to in Debian.". 25 October 2013. https://bugs.debian.org/cgi-bin/bugreport.cgi?bug=727708.

- ↑ "Which init system for Debian?". 5 November 2013. https://lwn.net/Articles/572805/.

- ↑ "Debian Still Debating systemd Vs. Upstart Init System". Phoronix. 30 December 2013. https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTU1NjA.

- ↑ "Losing graciously". 14 February 2014. https://www.markshuttleworth.com/archives/1316.

- ↑ "Quantal, raring, saucy...". 18 October 2013. https://www.markshuttleworth.com/archives/1295.

- ↑ Hess, Joey. "on leaving". https://joeyh.name/blog/entry/on_leaving/.

- ↑ Allbery, Russ (16 November 2014). "Resigning from the Technical Committee". debian-ctte (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ Jackson, Ian (19 November 2014). "Resignation". debian-ctte (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ Heen, Tollef Fog (16 November 2014). "Resignation from the pkg-systemd maintainer team". pkg-systemd-maintainers (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ Carroty, Paul (28 August 2015). "Lennart Poettering merged 'su' command replacement into systemd: Test Drive on Fedora Rawhide". https://tlhp.cf/lennart-poettering-su/.

- ↑ "Assertion failure when PID 1 receives a zero-length message over notify socket #4234". 28 September 2016. https://github.com/systemd/systemd/issues/4234.

- ↑ Felker, Rich (3 October 2016). "Hack Crashes Linux Distros with 48 Characters of Code". Kaspersky Lab. https://threatpost.com/hack-crashes-linux-distros-with-48-characters-of-code/121052/.

- ↑ CVE-2017-9445 Details, 6 July 2017, https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2017-9445, retrieved 6 July 2018

- ↑ CVE-2017-9445, 5 June 2017, https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2017-9445, retrieved 6 July 2018

- ↑ "Pwnie Awards 2017, Lamest Vendor Response: SystemD bugs". https://pwnies.com/systemd-bugs/.

- ↑ Gundersen, Tom E. (25 September 2014). "The End of Linux". http://blog.lusis.org/blog/2014/09/23/end-of-linux/#comment-1605841507. "It certainly is not something that comes with systemd from upstream."

- ↑ "The New Control Group Interfaces". Freedesktop.org. 28 August 2015. https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/ControlGroupInterface/.

- ↑ Poettering, Lennart (May 2014). "A Perspective for systemd: What Has Been Achieved, and What Lies Ahead". https://0pointer.de/public/gnomeasia2014.pdf.

- ↑ "What is systemd?". 11 September 2019. https://www.linode.com/docs/quick-answers/linux-essentials/what-is-systemd/.

- ↑ "Inhibitor Locks". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/inhibit/.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Poettering, Lennart (26 January 2013). "The Biggest Myths". https://0pointer.de/blog/projects/the-biggest-myths.html.

- ↑ "Debate/initsystem/systemd – Debian Documentation". Debian. 2 January 2014. https://wiki.debian.org/Debate/initsystem/systemd.

- ↑ Edge, Jake (7 November 2013). "Creating containers with systemd-nspawn". LWN.net. https://lwn.net/Articles/572957/.

- ↑ "ControlGroupInterface". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/ControlGroupInterface/.

- ↑ Heo, Tejun (28 January 2014). "cgroup: convert to kernfs". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Heo, Tejun (13 March 2014). "cgroup: prepare for the default unified hierarchy". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "systemd's binary logs and corruption". 17 February 2014. https://www.reddit.com/r/linux/comments/1y6q0l/systemds_binary_logs_and_corruption/.

- ↑ "systemd-logind.service". https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd-logind.service.html.

- ↑ "ConsoleKit official website". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/ConsoleKit/.

- ↑ "How to hook up your favorite X11 display manager with systemd". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/writing-display-managers/.

- ↑ "Networking in +systemd - 1. Background". 27 November 2013. https://plus.google.com/+TomGundersen/posts/bDQCP5ZyQ3h.

- ↑ "Networking in +systemd - 2. libsystemd-rtnl". 27 November 2013. https://plus.google.com/+TomGundersen/posts/JhaBNn8Ytwu.

- ↑ "Networking in +systemd - 3. udev". 27 November 2013. https://plus.google.com/+TomGundersen/posts/anS8GseSAfw.

- ↑ "Networking in +systemd - 4. networkd". 27 November 2013. https://plus.google.com/+TomGundersen/posts/8d1tzMJWppJ.

- ↑ "Networking in +systemd - 5. the immediate future". 27 November 2013. https://plus.google.com/+TomGundersen/posts/U6Es8bpmMbP.

- ↑ Larabel, Michael (4 July 2014). "systemd 215 Works On Factory Reset, DHCPv4 Server Support". https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTczNDA.

- ↑ Šimerda, Pavel (3 February 2013). "Can Linux network configuration suck less?". https://archive.fosdem.org/2013/schedule/event/dist_network/.

- ↑ – Linux User's Manual – User Commands

- ↑ "timedated". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/systemd/timedated/.

- ↑ Sievers, Kay. "The future of the udev source tree". vger.kernel.org/vger-lists.html#linux-hotplug linux-hotplug (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ↑ Sievers, Kay, Commit importing udev into systemd, https://cgit.freedesktop.org/systemd/systemd/commit/?id=19c5f19d69bb5f520fa7213239490c55de06d99d, retrieved 25 May 2012

- ↑ Proven, Liam. "Version 252 of systemd released" (in en). https://www.theregister.com/2022/11/03/version_252_systemd/.

- ↑ "[PATCH] Drop the udev firmware loader". systemd-devel (Mailing list). 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ↑ "systemd.syntax". https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd.syntax.html.

- ↑ "systemd.unit man page". freedesktop.org. https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd.unit.html.

- ↑ "systemd.device". https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd.device.html.

- ↑ "systemd Dreams Up New Feature, Makes It Like Cron". Phoronix. 28 January 2013. https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTI4NTk.

- ↑ "systemd.slice (5) - Linux Man Pages". https://www.systutorials.com/docs/linux/man/5-systemd.slice/. "... a slice ... is a concept for hierarchically managing resources of a group of processes."

- ↑ "systemd.scope". https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd.scope.html.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 "Git clone of the 'packages' repository". 12 January 2012. https://projects.archlinux.org/svntogit/packages.git/commit/trunk/PKGBUILD?h=packages%2Fsystemd&id=982ee75b9cda95d9357e9b80a931f7b52638c42b.

- ↑ "systemd is now the default on new installations". Arch Linux. https://www.archlinux.org/news/systemd-is-now-the-default-on-new-installations/.

- ↑ "coreos/manifest: Releases: v94.0.0". 3 October 2013. https://github.com/coreos/manifest/releases/tag/v94.0.0.

- ↑ CoreOS's init system, https://coreos.com/using-coreos/systemd/, retrieved 14 February 2014

- ↑ "systemd". https://packages.debian.org/search?keywords=systemd.

- ↑ Garbee, Bdale (11 February 2014). "Bug#727708: call for votes on default Linux init system for jessie". debian-ctte (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ "systemd - system and service manager". Installing without systemd. https://wiki.debian.org/systemd#Installing_without_systemd.

- ↑ "Fedora 14 talking points". https://fedoraproject.org/wiki/Fedora_14_talking_points#Systemd.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 systemd, https://wiki.gentoo.org/wiki/systemd, retrieved 26 August 2012

- ↑ "Installing the Gentoo Base System § Optional: Using systemd". https://www.gentoo.org/doc/en/handbook/handbook-x86.xml?part=1&chap=6#doc_chap3.

- ↑ Comment #210 (bug #318365), https://bugs.gentoo.org/show_bug.cgi?id=318365#c210, retrieved 5 July 2011

- ↑ systemd, https://www.gentoo.org/proj/en/base/systemd/, retrieved 5 July 2011

- ↑ https://www.gentoo.org/downloads/

- ↑ "KNOPPIX 7.4.2 Release Notes". http://www.knopper.net/knoppix/knoppix742-en.html. "...script-based KNOPPIX system start with sysvinit"

- ↑ "KNOPPIX 8.0 Die Antwort auf Systemd (German)". https://www.golem.de/news/live-linux-knoppix-8-0-bringt-moderne-technik-fuer-neue-hardware-1703-126811-3.html. "...Knoppix 'boot process continues to run via Sys-V init with few bash scripts that start the system services efficiently sequentially or in parallel. (The original German text: Knoppix' Startvorgang läuft nach wie vor per Sys-V-Init mit wenigen Bash-Skripten, welche die Systemdienste effizient sequenziell oder parallel starten.)"

- ↑ "LM Blog: both Mint 18 and LMDE 3 will switch to systemd.". https://blog.linuxmint.com/?p=2808#comment-116426.

- ↑ ChangeLog of Mageia's systemd package, https://rpmfind.net//linux/RPM/mageia/1/x86_64/media/core/release/systemd-18-1.mga1.x86_64.html, retrieved 19 March 2016

- ↑ Scherschel, Fabian (23 May 2012), Mageia 2 arrives with GNOME 3 and systemd, The H, http://h-online.com/-1582479, retrieved 22 August 2012

- ↑ "Mageia forum • View topic - is it possible to replace systemd?". https://forums.mageia.org/en/viewtopic.php?f=7&t=11169.

- ↑ Directory view of the 11.4 i586 installation showing presence of the systemd v18 installables, 23 February 2011, http://download.opensuse.org/distribution/11.4/repo/oss/suse/i586/, retrieved 24 September 2013

- ↑ "OpenSUSE: Not Everyone Likes systemd". Phoronix. https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTE4MDY. "The recently released openSUSE 12.2 does migrate from SysVinit to systemd"

- ↑ "Parabola ISO Download Page". https://wiki.parabola.nu/Get_Parabola.

- ↑ Red Hat Unveils Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7, 10 June 2014, https://www.redhat.com/about/news/press-archive/2014/6/red-hat-unveils-rhel-7, retrieved 19 March 2016

- ↑ "Initial entry of the "systemd" spell". http://scmweb.sourcemage.org/smgl/grimoire.git/commit/smgl/systemd?id=a635ca906741db0dcd2725fcf5fa4502693b98a4.

- ↑ "Void-Package: systemd: removed; no plans to resurrect this.". https://github.com/void-linux/void-packages/commit/dc6429e189adcaa775648c554256b877ae7fcefd.

- ↑ "Meet Devuan, the Debian fork born from a bitter systemd revolt". http://www.pcworld.com/article/2854717/meet-devuan-the-debian-fork-born-from-a-bitter-systemd-revolt.html.

- ↑ Sharwood, Simon (5 May 2017). "systemd-free Devuan Linux hits RC2". The Register. https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/05/05/devuan_release_candidate_2/.

- ↑ "Debian Developers Decide On Init System Diversity: "Proposal B" Wins". https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=Debian-Devs-Vote-For-Prop-B.

- ↑ Poettering, Lennart (18 May 2011). "systemd as an external dependency". desktop-devel (Mailing list). GNOME. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Peters, Frederic (4 November 2011). "20121104 meeting minutes". GNOME release-team (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ↑ "ConsoleKit". https://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/ConsoleKit/. "ConsoleKit is currently not actively maintained. The focus has shifted to the built-in seat/user/session management of Software/systemd called systemd-logind!"

- ↑ Vitters, Olav. "GNOME and logind+systemd thoughts". https://blogs.gnome.org/ovitters/2013/09/25/gnome-and-logindsystemd-thoughts/.

- ↑ "GNOME 3.10 arrives with experimental Wayland support". ZDNet. http://www.zdnet.com/gnome-3-10-arrives-with-experimental-wayland-support-7000021185/.

- ↑ "GNOME initiatives: systemd". https://wiki.gnome.org/Initiatives/Systemd.

- ↑ "Mutter 3.13.2: launcher: Replace mutter-launch with logind integration". 19 May 2014. https://git.gnome.org/browse/mutter/commit/?id=dcf64ca1678a2950842708bee146f09a063ed828.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven (19 September 2014). "Linus Torvalds and others on Linux's systemd". CBS Interactive. http://www.zdnet.com/article/linus-torvalds-and-others-on-linuxs-systemd/.

- ↑ "1345661 - PulseAudio requirement breaks Firefox on ALSA-only systems". Mozilla. 3 September 2021. https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/show_bug.cgi?id=1345661.

- ↑ "Interview with Patrick Volkerding of Slackware". 7 June 2012. https://www.linuxquestions.org/questions/interviews-28/interview-with-patrick-volkerding-of-slackware-949029/.

- ↑ "I'm back after a break from Slackware: sharing thoughts and seeing whats new!". https://www.linuxquestions.org/questions/slackware-14/i%27m-back-after-a-break-from-slackware-sharing-thoughts-and-seeing-whats-new-4175482641/#post5054861.

- ↑ Rich Felker (9 February 2014). "Broken by design: systemd". http://ewontfix.com/14/.

- ↑ "Interviews: ESR Answers Your Questions". Slashdot.org. 10 March 2014. https://interviews.slashdot.org/story/14/03/10/137246/interviews-esr-answers-your-questions.

- ↑ Torvalds, Linus (2 April 2014). "Re: [RFC PATCH] cmdline: Hide "debug" from /proc/cmdline". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ↑ "Is systemd as bad as boycott systemd is trying to make it?". LinuxBSDos.com. 3 September 2014. https://linuxbsdos.com/2014/09/03/is-systemd-as-bad-as-boycott-systemd-is-trying-to-make-it/.

- ↑ "Boycott systemd.org". http://boycottsystemd.org/.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Venezia, Paul (18 August 2014). "systemd: Harbinger of the Linux apocalypse". http://www.infoworld.com/article/2608798/data-center/systemd--harbinger-of-the-linux-apocalypse.html.

- ↑ "Linus Torvalds and others on Linux's systemd". http://www.zdnet.com/linus-torvalds-and-others-on-linuxs-systemd-7000033847/.

- ↑ "A realization that I recently came to while discussing the whole systemd...". 31 March 2014. https://plus.google.com/+TheodoreTso/posts/4W6rrMMvhWU.

- ↑ "FreeInit.org". https://freeinit.org/.

- ↑ "eudev/README". https://github.com/gentoo/eudev/blob/master/README.

- ↑ "Gentoo eudev project". https://wiki.gentoo.org/wiki/Project:Eudev.

- ↑ Basile, Anthony G. (24 August 2021). "eudev retirement on 2022-01-01". Gentoo Linux. https://www.gentoo.org/support/news-items/2021-08-24-eudev-retirement.html.

- ↑ "elogind/README". https://github.com/andywingo/elogind/blob/master/README.

- ↑ Koegel, Eric (20 October 2014). "ConsoleKit2". https://erickoegel.wordpress.com/2014/10/20/consolekit2/.

- ↑ "loginkit/README". https://github.com/dimkr/LoginKit/blob/master/README.

- ↑ "dimkr/LoginKit (Github)". https://github.com/dimkr/LoginKit/tree/master.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 "GSoC 2014: systemd replacement utilities (systembsd)". OpenBSD Journal. http://undeadly.org/cgi?action=article&sid=20140915064856.

- ↑ projects / systembsd.git / summary, https://uglyman.kremlin.cc/gitweb/gitweb.cgi?p=systembsd.git;a=summary, retrieved 8 July 2018

- ↑ Luke Shumaker (17 June 2017). "notsystemd v232.1 release announcement". Dev@lists.parabola.nu (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ "notsystemd". https://repo.parabola.nu/other/notsystemd/.

- ↑ Larabel, Michael (21 September 2014). "Uselessd: A Stripped Down Version Of systemd". Phoronix. https://www.phoronix.com/scan.php?page=news_item&px=MTc5MzA.

- ↑ "Uselessd is dead". http://uselessd.darknedgy.net/.

- ↑ "uselessd :: information system". http://uselessd.darknedgy.net/.

- ↑ "InitWare/InitWare: The InitWare Suite of Middleware allows you to manage services and system resources as logical entities called units. Its main component is a service management ("init") system." (in en). 14 November 2021. https://github.com/InitWare/InitWare.

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "ubuntu-init-switch" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

<ref> tag with name "launchpad-upstart-packages" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.External links

|

KSF

KSF