Ultima III

Topic: Software

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

| Ultima III: Exodus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Origin Systems |

| Publisher(s) | Origin Systems |

| Designer(s) | Richard Garriott |

| Composer(s) | Kenneth W. Arnold Tsugutoshi Gotō (NES) |

| Series | Ultima |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, Apple II, Atari 8-bit, Atari ST, Commodore 64, MS-DOS, FM-7, MSX2, Macintosh, NEC PC-8801, PC-98, NES, Sharp X1 |

| Release | August 23, 1983 |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Ultima III: Exodus is the third game in the series of Ultima role-playing video games. Exodus is also the name of the game's principal antagonist. It is the final installment in the "Age of Darkness" trilogy. Released in 1983,[1] it was the first Ultima game published by Origin Systems. Originally developed for the Apple II, Exodus was eventually ported to 13 other platforms, including a NES/Famicom remake.

Ultima III revolves around Exodus, the spawn of Mondain and Minax (from Ultima I and Ultima II, respectively), threatening the world of Sosaria. The player character travels to Sosaria to defeat Exodus and restore the world to peace.[2] Ultima III hosts further advances in graphics, particularly in animation, adds a musical score, and increases the player's options in gameplay with a larger party and more interactivity with the game world.

Ultima III was followed by Ultima IV in 1985.

Gameplay

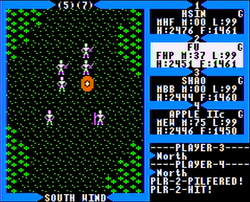

Exodus featured revolutionary graphics for its time, as one of the first computer RPGs to display animated characters. Also, Exodus differs from previous games in that players now direct the actions of a party of four characters rather than just one.[3] During regular play the characters are represented as a single player icon and move as one. However, in battle mode, each character is represented separately on a tactical battle screen, and the player alternates commands between each character in order, followed by each enemy character having a turn. This differs from the two previous games in the Ultima series in which the player is simply depicted as trading blows with one opponent on the main map until either is defeated. Enemies on the overworld map can be seen and at least temporarily avoided, while enemies in dungeons appear randomly without any forewarning.

The party of four that a player uses can be chosen at the beginning of the game. There is a choice between 11 classes: Fighter, Paladin, Cleric, Wizard, Ranger, Thief, Barbarian, Lark, Illusionist, Druid, and Alchemist. The player also chooses from among five races: Human, Elf, Dwarf, Bobbit, or Fuzzy. Players then assign points to their statistics: Strength, Dexterity, Intelligence, and Wisdom. The races determine limitations on maximum stat growth, and thus (in the case of Intelligence and Wisdom) maximum spellcasting ability.[2]

Character classes differ in terms of fighting skill, magical abilities, and thieving abilities, with varying degrees of proficiency in each. Fighters, for example, can use all weapons and armor, but lack thieving or magic abilities; clerics can use up to maces and chain armor, and all clerical spells; Alchemists can use only daggers and cloth armor, and half wizard spells and half thieving abilities.[2]

Each character begins at Level 1 and increases individually.[2] The maximum effective level for characters is 25. Beyond this point the level will continue to increase; however the number of hit points is fixed at 2550. Maximum hit points for a character can be calculated by the following formula: HP = 100 * L + 50 (where L is the current level of the character). When a character has gained enough experience points, they must transact with Lord British for the character to level up.

Aside from the ability to talk to townspeople there are other commands that can be used on them. Some of the commands a player can use are bribe, steal, and fight. Bribing can be used to make certain guards go away from their post. Steal can be used on townspeople and some enemies, but can result in conflict with townspeople if caught. A player can choose to fight a townsperson, but it will prompt the guards to chase after the player characters. The guards always come in parties of eight and are very difficult to defeat. You can also choose to fight Lord British, but he cannot be killed, thus resulting in a long, drawn-out fight that the player will ultimately lose. Lord British can be temporarily killed by cannon fire from a ship in the castle moat, but exiting and re-entering the castle restores him.

Unlike the two previous Ultima games, which had wire-frame first-person dungeons, Exodus dungeons are solid-3D in appearance and integrated into the game's plot.[2] Dungeons are necessary to obtain certain marks that are needed to finish the game. Each dungeon has 8 levels, and the deeper the level the more challenging the enemies. Note: the monsters that are spawned in dungeons are not based on character level as the overworld monsters are; rather, they are based on the dungeon level they are encountered in, so going too deep into certain dungeons may be too hard for characters in the early stages of the game. One can find many chests (with gold, weapons, and armor) inside dungeons, but many of them are trapped. Aside from chests and marks, one can find fountains in dungeons: some heal, some cure, and some poison. Peering at gems allows the player to see a map of a given dungeon level; torches or light-casting spells are necessary to be able to see inside dungeons.[2]

There are three modes of travel in the game: on foot, horseback, and boat.[2] Getting around on foot is slow and can often lead to monsters catching up to the player character. Horseback gives the player character the advantage of moving faster while consuming less food, making getting away from unwanted fights easier. Getting a boat requires players to reach a certain level so that pirate ships begin appearing. Once a pirate ship is defeated, the boat belongs to the player. Obtaining a boat is necessary in order to visit the island of Ambrosia, and to reach Exodus and thus win the game.

By denying the player the ability to see what's behind mountain peaks, forests, and walls, the overland maps contain many small surprises such as hidden treasure, secret paths, and out-of-the-way informants. The look of the game is no longer based on certain characteristics of the Apple II hardware; it is rather a carefully designed screen layout.[citation needed]

Beating the game requires the player to get all four marks and all four prayer cards. At the altar of Exodus, the player character must insert the cards in a particular order to defeat Exodus.

Plot

After Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress was set on Earth,[4] the story of Exodus returns the player to Sosaria, the world of Ultima I.[5] The game is named for its chief villain, Exodus, a creation of Minax and Mondain that the series later describes as neither human nor machine. Although a demonic figure appears on the cover of the game, Exodus turns out to something like a computer (possibly an artificial intelligence) and to defeat him the player has to acquire four magic (punch)cards and insert them into the mainframe in a specific order.[6]

At the beginning of the game, Exodus is terrorizing the land of Sosaria from his stronghold on the Isle of Fire. The player is summoned by Lord British to defeat Exodus, and embarks on a quest that takes him to the lost land of Ambrosia, to the depths of the dungeons of Sosaria to receive powerful magical branding marks and to find the mysterious Time Lord, and finally to the Isle of Fire itself to confront Exodus in his lair.[2]

The game ends immediately upon Exodus' defeat; but unlike many games in the genre, Exodus cannot simply be killed in battle by a strong party of adventurers, but only through puzzle-solving and by paying attention to the clues given throughout the game. At the end of the game, players were instructed to "REPORT THY VICTORY!" to Origin. Those who did so received a certificate of completion autographed by Richard Garriott.[citation needed]

Places in the game such as Ambrosia and the Isle of Fire make appearances in later games, such as Ultima VII and Ultima Online.[citation needed]

Development

Ultima III was the first game in the series published by Richard Garriott's company Origin Systems.[7] Ports appeared on many different systems.

| System | Release date | Publisher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apple II | 1983 | Origin Systems |

|

| Atari 800 | 1983 | Origin Systems |

|

| Commodore 64 | 1983 | Origin Systems |

|

| IBM PC | 1983 | Origin Systems |

|

| Amiga | 1986 | Origin Systems |

|

| Atari ST | 1986 | Origin Systems |

|

| Macintosh | 1986 | Origin Systems |

|

| PC-8801 | 1986 | Starcraft* |

|

| PC-9801 | 1986 | Starcraft* |

|

| FM-7 | 1986 | Starcraft* |

|

| NES/Famicom | 1987 | FCI/Pony Canyon |

|

| MSX2 - Cartridge | 1988 | Pony Canyon |

|

| MSX2 - 3.5" Disk | 1989 | Pony Canyon |

|

| Macintosh | 1993 | LairWare |

|

- *The publisher Starcraft has no relation to the video game StarCraft and went out of business in 1996.

Reception and legacy

Ultima III sold over 100,000 copies by August 1986,[9] and over 120,000 copies by 1990.[10] Video magazine listed the game seventh on its list of best selling video games in March 1985[11] with II Computing listing it fifth on the magazine's list of top Apple II games as of late 1985, based on sales and market-share data.[12]

Exodus is credited as a game that laid the foundation for the role-playing video game genre, influencing games such as Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy.[13] In turn, Exodus was itself influenced by Wizardry, which Richard Garriot credited as the inspiration behind the party-based combat in his game.[14] Computer Gaming World stated in February 1994 that Exodus "was the game that became known as Ultima to hundreds of thousands of cartridge gamers".[15]

Softline stated that Ultima III "far surpasses" its predecessors, praising the "masterfully unified" plot and individual tactical combat. The magazine concluded that the game "upgrades the market; in several ways it sets new standards for the fantasy gaming state of the art. Happily, it also shows us a maturing artistic discipline on the part of its imaginative author".[16] Computer Gaming World's Scorpia in 1983 called Ultima III "unquestionably the best in the series so far ... many hours of enjoyment (and frustration!)", although she criticized the ending as anticlimactic.[17] The magazine's Patricia Fitzgibbons in 1985 reviewed the Macintosh version. She complimented its graphics but criticized the audio, and stated that the game did not adequately use the computer's user interface, describing using the mouse as "aggravating". Fitzgibbons concluded "Even though the Mac conversion is far from ideal, Ultima III is a very enjoyable game, and well worth its hefty price".[18] In 1993 Scorpia stated that Ultima III was the best of the first trilogy, and that its "surprisingly quiet and nonviolent" defeat of the villain presaged the later games' "resolutions that are less combative in spirit".[19] The magazine stated in February 1994 that Exodus "was really the first [Ultima] to have a coherent plot beyond the typical dungeon romp".[15]

Compute! in 1984 stated that Ultima III "ushers in an exciting new era of fantasy role-playing. The combination of superb graphics, music, and excellent playability makes Exodus a modern-day masterpiece". It noted the cloth map and the extensive documentation, the "thrilling" 3-D dungeons, the game's use of time, and the spell system. The magazine concluded, "Lord British has outdone himself with his latest work of art ... a delight to play".[20] INFO stated that "Lord British's latest offering is also his best ... Many wonderful hours will be spent unravelling its secrets".[21] The magazine gave the Amiga version four stars compared to five stars for the 64 version, stating that "the graphics and user interface could have been better Amiga-tized".[22] The Chicago Tribune called Ultima III "one of the best" computer games, providing "an epic adventure which can last for months".[23] Famitsu reviewed the 1987 Famicom remake and scored it 32 out of 40.[24]

In 1984 Softline readers named the game the third most-popular Apple and eighth most-popular Atari program of 1983.[25] It won the Adventure Game of the Year prize in Computer Gaming World's 1985 reader poll, about which the editors wrote "Although Ultima III has been out well over a year, we feel that it is still the best game of its kind."[26] With a score of 7.55 out of 10, in 1988 Ultima III was among the first members of the Computer Gaming World Hall of Fame, honoring those games rated highly over time by readers.[27] In 1996, the magazine ranked it as the 144th best game of all time, featuring "one of the nastiest villains to grace a computer screen".[28]

The demon figure that appeared on the front of the box caused some religious fundamentalists to protest. They made accusations that the game was corrupting the youth of America and encouraging Satan worshiping.[29] This, along with other factors, led Richard Garriott to develop his next game (Ultima IV) based on the virtues the Ultima series became famous for.[30]

Reviews

References

- ↑ (USCO# PA-317-503)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Ultima III: Exodus Book of Play. Origin Systems. 1983.

- ↑ "The Ultima Time Line". Next Generation (Imagine Media) (39): 65. March 1998.

- ↑ Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress Manual. Sierra On-Line. 1982.

- ↑ Origin Systems (1986). Ultima I: The First Age of Darkness Manual.

- ↑ "Ultima III: Exodus". 12 December 2012. http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/ultima-iii-exodus/.

- ↑ Garriott, Richard (July 1988). "Lord British Kisses and Tells All / as told by His Royal Highness, High King of Britannia". Computer Gaming World: 28. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1988&pub=2&id=49. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Ultima III". LairWare. http://www.lairware.com/ultima3/.

- ↑ Petska-Juliussen, Karen; Juliussen, Egil (1990). The Computer Industry Almanac 1990. New York: Brady. pp. 3.12. ISBN 978-0-13-154122-1. https://archive.org/details/computerindustry00kare/page/n267/mode/2up.

- ↑ The Official Book Of Ultima (second ed.). 1990. p. 35. https://archive.org/details/TheOfficialBookOfUltima/page/n47.

- ↑ Onosco, Tim; Kohl, Louise; Kunkel, Bill; Garr, Doug (March 1985). "Random Access: Best Sellers/Recreation". Video (Reese Communications) 8 (12): 43. ISSN 0147-8907.

- ↑ Ciraolo, Michael (October–November 1985). "Top Software / A List of Favorites". II Computing: pp. 51. https://archive.org/stream/II_Computing_Vol_1_No_1_Oct_Nov_85_Premiere#page/n51/mode/2up.

- ↑ Matt Barton (February 23, 2007). "The History of Computer Role-Playing Games Part 1: The Early Years (1980-1983)". http://www.gamasutra.com/features/20070223a/barton_04.shtml.

- ↑ Barton, Matt (2008). Dungeons & Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games. A K Peters, Ltd.. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-56881-411-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=IMXu61GbTqMC&q=japanese. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Computer Gaming World Hall of Fame". Computer Gaming World: 221. February 1994. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1994&pub=2&id=115.

- ↑ Durkee, David (Nov–Dec 1983). "Exodus: Ultima III". Softline: pp. 16–17. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1983&pub=6&id=14.

- ↑ Scorpia (December 1983). "Ultima III: Review & Tips". Computer Gaming World: 18–19, 51. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1983&pub=2&id=13. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ↑ Fitzgibbons, Patricia (November–December 1985). "Ultima III / The Macintosh Version". Computer Gaming World: 47. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1985&pub=2&id=24. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Scorpia (October 1993). "Scorpia's Magic Scroll Of Games". Computer Gaming World: 34–50. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1993&pub=2&id=111. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Peacock, David K. (September 1984). "Exodus: Ultima III For Commodore 64". Compute!: pp. 106. https://archive.org/stream/1984-09-compute-magazine/Compute_Issue_052_1984_Sep#page/n107/mode/2up.

- ↑ Salamone, Ted (1984). "Exodus: Ultima III". INFO (5): 35. https://archive.org/stream/info-magazine-05/Info_Issue_05#page/n33/mode/2up.

- ↑ Dunnington, Benn; Brown, Mark R.; Malcolm, Tom (January–February 1987). "Amiga Gallery". Info: 90–95. https://archive.org/stream/info-magazine-13/Info_Issue_13_1987_Jan-Feb#page/n89/mode/2up.

- ↑ Kosek, Steven (1985-02-15). "Ultima III conjures up an epic video adventure game". Chicago Tribune: pp. Section 7, Page 61. http://archives.chicagotribune.com/1985/02/15/page/147/article/ultima-iii-conjures-up-an-epic-video-adventure-game.

- ↑ "ウルティマ 〜恐怖のエクソダス〜 [ファミコン / ファミ通.com"]. http://www.famitsu.com/cominy/?m=pc&a=page_h_title&title_id=19749.

- ↑ "The Best and the Rest". St.Game: pp. 49. Mar–Apr 1984. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1984&pub=6&id=16.

- ↑ "Game of the Year". Computer Gaming World: pp. 32–33. November–December 1985. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1985&pub=2&id=24.

- ↑ "The CGW Hall of Fame". Computer Gaming World: 44. March 1988. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1988&pub=2&id=45. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World: 64–80. November 1996. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1996&pub=2&id=148. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ The Official Book of Ultima, page 34

- ↑ The Official Book of Ultima, page 39

- ↑ "Ludotique | Article | RPGGeek". https://www.rpggeek.com/rpgissuearticle/142014/ludotique.

- ↑ "Ludotique | Article | RPGGeek". https://www.rpggeek.com/rpgissuearticle/139395/ludotique.

External links

- MobyGames is a commercial database website that catalogs information on video games and the people and companies behind them via crowdsourcing. This includes over 300,000 games for hundreds of platforms.[1] Founded in 1999, ownership of the site has changed hands several times. It has been owned by Atari SA since 2022.

Features

Edits and submissions to the site (including screenshots, box art, developer information, game summaries, and more) go through a verification process of fact-checking by volunteer "approvers".[2] This lengthy approval process after submission can range from minutes to days or months.[3] The most commonly used sources are the video game's website, packaging, and credit screens. There is a published standard for game information and copy-editing.[4] A ranking system allows users to earn points for contributing accurate information.[5]

Registered users can rate and review games. Users can create private or public "have" and "want" lists, which can generate a list of games available for trade with other registered users. The site contains an integrated forum. Each listed game can have its own sub-forum.

History

MobyGames was founded on March 1, 1999, by Jim Leonard and Brian Hirt, and joined by David Berk 18 months later, the three of which had been friends since high school.[6][7] Leonard had the idea of sharing information about computer games with a larger audience. The database began with information about games for IBM PC compatibles, relying on the founders' personal collections. Eventually, the site was opened up to allow general users to contribute information.[5] In a 2003 interview, Berk emphasized MobyGames' dedication to taking video games more seriously than broader society and to preserving games for their important cultural influence.[5]

In mid-2010, MobyGames was purchased by GameFly for an undisclosed amount.[8] This was announced to the community post factum , and the site's interface was given an unpopular redesign.[7] A few major contributors left, refusing to do volunteer work for a commercial website.{{Citation needed|date=June 2025} On December 18, 2013, MobyGames was acquired by Jeremiah Freyholtz, owner of Blue Flame Labs (a San Francisco-based game and web development company) and VGBoxArt (a site for fan-made video game box art).[9] Blue Flame Labs reverted MobyGames' interface to its pre-overhaul look and feel,[10] and for the next eight years, the site was run by Freyholtz and Independent Games Festival organizer Simon Carless.[7]

On November 24, 2021, Atari SA announced a potential deal with Blue Flame Labs to purchase MobyGames for $1.5 million.[11] The purchase was completed on 8 March 2022, with Freyholtz remaining as general manager.[12][13][14] Over the next year, the financial boost given by Atari led to a rework of the site being built from scratch with a new backend codebase, as well as updates improving the mobile and desktop user interface.[1] This was accomplished by investing in full-time development of the site instead of its previously part-time development.[15]

In 2024, MobyGames began offering a paid "Pro" membership option for the site to generate additional revenue.[16] Previously, the site had generated income exclusively through banner ads and (from March 2014 onward) a small number of patrons via the Patreon website.[17]

See also

- IGDB – game database used by Twitch for its search and discovery functions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheehan, Gavin (2023-02-22). "Atari Relaunches The Fully Rebuilt & Optimized MobyGames Website". https://bleedingcool.com/games/atari-relaunches-the-fully-rebuilt-optimized-mobygames-website/.

- ↑ Litchfield, Ted (2021-11-26). "Zombie company Atari to devour MobyGames". https://www.pcgamer.com/zombie-company-atari-to-devour-mobygames/.

- ↑ "MobyGames FAQ: Emails Answered § When will my submission be approved?". Blue Flame Labs. 30 March 2014. http://www.mobygames.com/info/faq7#g1.

- ↑ "The MobyGames Standards and Practices". Blue Flame Labs. 6 January 2016. http://www.mobygames.com/info/standards.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Miller, Stanley A. (2003-04-22). "People's choice awards honor favorite Web sites". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ↑ "20 Years of MobyGames" (in en). 2019-02-28. https://trixter.oldskool.org/2019/02/28/20-years-of-mobygames/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Plunkett, Luke (2022-03-10). "Atari Buys MobyGames For $1.5 Million". https://kotaku.com/mobygames-retro-credits-database-imdb-atari-freyholtz-b-1848638521.

- ↑ "Report: MobyGames Acquired By GameFly Media". Gamasutra. 2011-02-07. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/game-platforms/report-mobygames-acquired-by-gamefly-media.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (December 31, 2013). "MobyGames purchased from GameFly, improvements planned". http://www.polygon.com/2013/12/31/5261414/mobygames-purchased-from-gamefly-improvements-planned.

- ↑ Wawro, Alex (31 December 2013). "Game dev database MobyGames getting some TLC under new owner". Gamasutra. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/business/game-dev-database-mobygames-getting-some-tlc-under-new-owner.

- ↑ "Atari invests in Anstream, may buy MobyGames". November 24, 2021. https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2021-11-24-atari-invests-in-anstream-may-buy-mobygames.

- ↑ Rousseau, Jeffrey (2022-03-09). "Atari purchases Moby Games". https://www.gamesindustry.biz/atari-purchases-moby-games.

- ↑ "Atari Completes MobyGames Acquisition, Details Plans for the Site's Continued Support". March 8, 2022. https://www.atari.com/atari-completes-mobygames-acquisition-details-plans-for-the-sites-continued-support/.

- ↑ "Atari has acquired game database MobyGames for $1.5 million" (in en-GB). 2022-03-09. https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/atari-has-acquired-game-database-mobygames-for-1-5-million/.

- ↑ Stanton, Rich (2022-03-10). "Atari buys videogame database MobyGames for $1.5 million". https://www.pcgamer.com/atari-buys-videogame-database-mobygames-for-dollar15-million/.

- ↑ Harris, John (2024-03-09). "MobyGames Offering “Pro” Membership". https://setsideb.com/mobygames-offering-pro-membership/.

- ↑ "MobyGames on Patreon". http://www.patreon.com/mobygames.

Wikidata has the property:

|

External links

- No URL found. Please specify a URL here or add one to Wikidata.

|

|

KSF

KSF