Telephone number

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

A telephone number is the address of a telecommunication endpoint, such as a telephone, in a telephone network, such as the public switched telephone network (PSTN). A telephone number typically consists of a sequence of digits, but historically letters were also used in connection with telephone exchange names.

Telephone numbers facilitate the switching and routing of calls using a system of destination code routing.[1] Telephone numbers are entered or dialed by a calling party on the originating telephone set, which transmits the sequence of digits in the process of signaling to a telephone exchange. The exchange completes the call either to another locally connected subscriber or via the PSTN to the called party. Telephone numbers are assigned within the framework of a national or regional telephone numbering plan to subscribers by telephone service operators, which may be commercial entities, state-controlled administrations, or other telecommunication industry associations.

Telephone numbers were first used in 1879 in Lowell, Massachusetts, when they replaced the request for subscriber names by callers connecting to the switchboard operator.[2] Over the course of telephone history, telephone numbers had various lengths and formats and even included most letters of the alphabet in leading positions when telephone exchange names were in common use until the 1960s.

Telephone numbers are often dialed in conjunction with other signaling code sequences, such as vertical service codes, to invoke special telephone service features.[3][4] Telephone numbers may have associated short dialing codes, such as 9-1-1, which obviate the need to remember and dial complete telephone numbers.

Concept and methodology

When telephone numbers were first used they were very short, from one to three digits, and were communicated orally to a switchboard operator when initiating a call. As telephone systems have grown and interconnected to encompass worldwide communication, telephone numbers have become longer. In addition to telephones, they have been used to access other devices, such as computer modems, pagers, and fax machines. With landlines, modems and pagers falling out of use in favor of all-digital always-connected broadband Internet and mobile phones, telephone numbers are now often used by data-only cellular devices, such as some tablet computers, digital televisions, video game controllers, and mobile hotspots, on which it is not even possible to make or accept a call.

The number contains the information necessary to identify the intended endpoint for a telephone call. Many countries use fixed-length numbers in a so-called closed numbering plan.[5] A prominent system of this type is the North American Numbering Plan. In Europe, the development of open numbering plans was more prevalent, in which a telephone number comprised a varying count of digits. Irrespective of the type of numbering plan, "shorthand" or "speed calling" numbers are automatically translated to unique telephone numbers before the call can be connected. Some special services have special short codes (e.g., 119, 911, 100, 101, 102, 000, 999, 111, and 112 being the emergency telephone numbers in many countries).

The dialing procedures (dialing plan) in some areas permit dialing numbers in the local calling area without using an area code or city code prefix. For example, a telephone number in North America consists of a three-digit area code, a three-digit central office code, and four digits for the line number. If the numbering plan area does not use an overlay plan with multiple area codes, or if the provider allows it for other technical reasons, seven-digit dialing may be permissible for calls within the area.

Special telephone numbers are used for high-capacity numbers with several telephone circuits, typically a request line to a radio station where dozens or even hundreds of callers may be trying to call in at once, such as for a contest. For each large metro area, all of these lines will share the same prefix (such as 404-741-xxxx in Atlanta and 305-550-xxxx in Miami), the last digits typically corresponding to the station's frequency, callsign, or moniker.

In the international telephone network, the format of telephone numbers is standardized by ITU-T recommendation E.164. This code specifies that the entire number should be 15 digits or shorter, and begin with an international calling prefix and a country prefix. For most countries, this is followed by an area code, city code or service number code and the subscriber number, which might consist of the code for a particular telephone exchange. ITU-T recommendation E.123 describes how to represent an international telephone number in writing or print, starting with a plus sign ("+") and the country code. When calling an international number from a landline phone, the + must be replaced with the international call prefix chosen by the country the call is being made from. Many mobile phones allow the + to be entered directly, by pressing and holding the "0" for GSM phones, or sometimes "*" for CDMA phones.

The 3GPP standards for mobile networks provide a BCD-encoded field of ten bytes for the telephone number ("Dialling Number/SCC String"). The international call prefix or "+" is not counted as it encodes a value in a separate byte (TON/NPI - type of number / numbering plan identification). If the MSISDN is longer than 20 digits then additional digits are encoded into extension blocks (EFEXT1) each having a BCD-encoded field of 11 bytes.[6] This scheme allows to extend the subscriber number with a maximum of 20 digits by additional function values to control network services. In the context of ISDN the function values were transparently transported in a BCD-encoded field with a maximum of 20 bytes named "ISDN Subaddress".[7]

The format and allocation of local telephone numbers are controlled by each nation's respective government, either directly or by sponsored organizations (such as NANPA in the US or CNAC in Canada). In the United States, each state's public service commission regulates, as does the Federal Communications Commission. In Canada, which shares the same country code with the U.S. (due to Bell Canada's previous ownership by the U.S.-based Bell System), regulation is mainly through the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission.

Local number portability (LNP) allows a subscriber to request moving an existing telephone number to another telephone service provider. Number portability usually has geographic limitations, such as an existing local telephone company only being able to port to a competitor within the same rate centre. Mobile carriers may have much larger market areas, and can assign or accept numbers from any area within the region. In many telephone administrations, mobile telephone numbers are in organized in prefix ranges distinct from land line service, which simplifies mobile number portability, even between carriers.

Within most North American rate centres, local wireline calls are free, while calls to all but a few nearby rate centres are considered long distance and incur toll fees. In a few large US cities, as well as many points outside North America, local calls are not flat-rated or "free" by default.

History

United States

Charles Williams Jr. owned a Boston shop where Bell and Watson made experiments and later produced their telephones. This equipment company was purchased by Western Electric in 1882 and Williams became manager of this initial manufacturing plant until retiring in 1886, remaining a director in Western Electric. His residence was phone number 1 and his shop was phone number 2 in Boston.[8]

In the late 1870s, the Bell interests started utilizing their patent with a rental scheme, in which they would rent their instruments to individual users who would contract with other suppliers to connect them; for example from home to office to factory. Western Union and the Bell company both soon realized that a subscription service would be more profitable, with the invention of the telephone switchboard or central office. Such an office was staffed by an operator who connected the calls by personal names. Some have argued that use of the telephone altered the physical layout of American cities.[9]

The latter part of 1879 and the early part of 1880 saw the first use of telephone numbers at Lowell, Massachusetts. During an epidemic of measles, the physician, Dr. Moses Greeley Parker, feared that Lowell's four telephone operators might all succumb to sickness and bring about paralysis of telephone service. He recommended the use of numbers for calling Lowell's more than 200 subscribers so that substitute operators might be more easily trained in such an emergency.[2] Parker was convinced of the telephone's potential, began buying stock, and by 1883 he was one of the largest individual stockholders in both the American Telephone Company and the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company.

Even after the assignment of numbers, operators still connected most calls into the early 20th century: "Hello, Central. Get me Underwood-342." Connecting through operators or "Central" was the norm until mechanical direct-dialing of numbers became more common in the 1920s.

In rural areas with magneto crank telephones connected to party lines, the local phone number consisted of the line number plus the ringing pattern of the subscriber. To dial a number such as "3R122" meant making a request to the operator the third party line (if making a call off your own local one), followed by turning the telephone's crank once, a short pause, then twice and twice again.[10] Also common was a code of long and short rings, so one party's call might be signaled by two longs and another's by two longs followed by a short.[11] It was not uncommon to have over a dozen ring cadences (and subscribers) on one line.

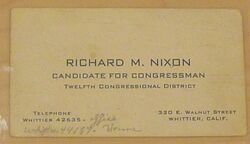

In most areas of North America, telephone numbers in metropolitan communities consisted of a combination of digits and letters, starting in the 1920s until the 1960s. Letters were translated to dialed digits, a mapping that was displayed directly on the telephone dial. Each of the digits 2 to 9, and sometimes 0, corresponded to a group of typically three letters. The leading two or three letters of a telephone number indicated the exchange name, for example, EDgewood and IVanhoe, and were followed by 5 or 4 digits. The limitations that these systems presented in terms of usable names that were easy to distinguish and spell, and the need for a comprehensive numbering plan that enabled direct-distance dialing, led to the introduction of all-number dialing in the 1960s.

The use of numbers starting in 555- (KLondike-5) to represent fictional numbers in U.S. movies, television, and literature originated in this period. The "555" prefix was reserved for telephone company use and was only consistently used for directory assistance (information), being "555–1212" for the local area. An attempt to dial a 555 number from a movie in the United States results in an error message. This reduces the likelihood of nuisance calls. QUincy(5–5555) was also used, because there was no Q available. Phone numbers were traditionally tied down to a single location; because exchanges were "hard-wired", the first three digits of any number were tied to the geographic location of the exchange.

Alphanumeric telephone numbers

The North American Numbering Plan of 1947 prescribed a format of telephone numbers that included two leading letters of the name of the central office to which each telephone was connected. This continued the practice already in place by many telephone companies for decades. Traditionally, these names were often the names of towns, villages, or were other locally significant names. Communities that required more than one central office may have used other names for each central office, such as "Main", "East", " Central" or the names of local districts. Names were convenient to use and reduced errors when telephone numbers were exchanged verbally between subscribers and operators. When subscribers could dial themselves, the initial letters of the names were converted to digits as displayed on the rotary dial. Thus, telephone numbers contained one, two, or even three letters followed by up to five numerals. Such numbering plans are called 2L-4N, or simply 2–4, for example, as shown in the photo of a telephone dial of 1939 (right). In this example, LAkewood 2697 indicates that a subscriber dialed the letters L and A, then the digits 2, 6, 9, and 7 to reach this telephone in Lakewood, NJ (USA). The leading letters were typically bolded in print.

In December 1930, New York City became the first city in the United States to adopt the two-letter and five-number format (2L-5N), which became the standard after World War II, when the Bell System administration designed the North American Numbering Plan to prepare the United States and Canada for Direct Distance Dialing (DDD), and began to convert all central offices to this format. This process was complete by the early 1960s, when a new numbering plan, often called all number calling (ANC) became the standard in North America.

United Kingdom

This article appears to contradict the article Telephone numbers in the United Kingdom. (May 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In the UK, letters were assigned to numbers in a similar fashion to North America, except that the letter O was allocated to the digit 0 (zero); digit 6 had only M and N. The letter Q was later added to the zero position on British dials, in anticipation of direct international dialing to Paris, which commenced in 1963. This was necessary because French dials already had Q on the zero position, and there were exchange names in the Paris region which contained the letter Q.

Most of the United Kingdom had no lettered telephone dials until the introduction of Subscriber Trunk Dialing (STD) in 1958. Until then, only the director areas (Birmingham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Liverpool, London and Manchester) and the adjacent non-director areas had the lettered dials; the director exchanges used the three-letter, four-number format. With the introduction of trunk dialing, the need for all callers to be able to dial numbers with letters in them led to the much more widespread use of lettered dials. The need for dials with letters ceased with the conversion to all-digit numbering in 1968.

Intercepted number

In the middle 20th century in North America when a call could not be completed, for example because the phone number was not assigned, had been disconnected, or was experiencing technical difficulties, the call was routed to an intercept operator who informed the caller. In the 1970s this service was converted to Automatic Intercept Systems which automatically choose and present an appropriate intercept message. Disconnected numbers are reassigned to new users after the rate of calls to them declines.

Outside of North America operator intercept was rare, although it did exist, for example it was sometimes used in Ireland. However, in most cases, calls to unassigned or disconnected numbers resulted in an automated message, either giving specific or a generic recorded error message. Some networks and equipment simply returned a number unobtainable, reorder or SIT (special information) tone to indicate an error.

In some networks recordings for error messages were (and still are) preceded by an SIT tone. This is particularly useful in multilingual contexts as the tone indicates an error has been encountered, even if the message cannot be understood by the caller and can be interpreted as an error by some auto-dialling equipment.

Special feature codes

Telephone numbers are sometimes prefixed with special services, such as vertical service codes, that contain signaling events other than numbers, most notably the star (*) and the number sign (#).[3] Vertical service codes enable or disable special telephony services either on a per-call basis, or for the station or telephone line until changed.[4] The use of the number sign is most frequently used as a marker signal to indicate the end of digit sequences or the end of other procedures; as a terminator it avoids operational delays when waiting for expiration of automatic time-out periods.

In popular culture

Fictitious telephone numbers are often used in films and on television to avoid disturbances by calls from viewers. For example, The United States 555 (KLondike-5) exchange code was never assigned (with limited exceptions such as 555–1212 for directory assistance). Therefore, American films and TV shows have used 555-xxxx numbers, in order to prevent a number used in such a work from being called.[12]

The film Bruce Almighty (2003) originally featured a number that did not have the 555 prefix. In the cinematic release, God (Morgan Freeman) leaves 776–2323 on a pager for Bruce Nolan (Jim Carrey) to call if he needed God's help. The DVD changes this to a 555 number. According to Universal Studios, which produced the movie, the number it used was picked because it did not exist in Buffalo, New York, where the movie was set. It did exist in other cities, resulting in customers' having that number receiving random calls from people asking for God. While some played along with the gag, others found the calls aggravating.[13][14]

The number in the Glenn Miller Orchestra's hit song "Pennsylvania 6-5000" (1940) is the number of the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City. The number is now written as 1-212-736-5000. According to the hotel's website, PEnnsylvania 6-5000 is New York's oldest continually assigned telephone number and possibly the oldest continuously-assigned number in the world.[15][16]

Australian films and television shows do not employ any recurring format for fictional telephone numbers; any number quoted in such media may be used by a real subscriber. The 555 code is used in the Balmain area of Sydney and the suburbs of Melbourne. Although in many areas being a prefix of 55 plus the thousand digit of 5 (e.g. 55 5XXX), would be valid, the numbering system was changed so that 555 became 9555 in Sydney and Melbourne, and in the country, there are two new digits ahead of the 55.[12]

Tommy Tutone's 1981 hit song "867-5309/Jenny" led to many unwanted calls by the public to telephone subscribers who actually were assigned that number.[17]

See also

Note: This topic belongs to "Telephones" portal

- Geographic number

- List of telephone country codes

- National conventions for writing telephone numbers

- Number translation service

- Phoneword

- Vanity number

- Short code

- Zenith number

- Caller ID

- Automatic number identification (ANI)

- Automatic number announcement circuit (ANAC)

- Dialed Number Identification Service (DNIS)

- Carrier access code (CAC)/Carrier identification code (CIC)

- IP address

- International mobile subscriber identity

- Mobile identification number

- Plant test number

References

- ↑ AT&T, Notes on Distance Dialing (1968), Section II, p.1

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Brooks, John.Telephone: The First Hundred Years. Harper & Row, 1967, ISBN 0-06-010540-2: p. 74 , citing "Events in Telephone History".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bellcore SR-2275 Bellcore Notes on the Network, Issue 3, Section 3 page 15. (December 1997)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "NANPA definition of vertical service codes". https://www.nationalnanpa.com/number_resource_info/vsc_definitions.html.

- ↑ O. Myers, C. A. Dahlbom, Overseas Dialing: A Step Toward Worldwide Communication, Telephone Engineer & Management Vol 65(22), 46 (1961-11-15) p.49

- ↑ "Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS); LTE; Characteristics of the Universal Subscriber Identity Module (USIM) application (3GPP TS 31.102 version 9.18.1 Release 9)". ETSI. April 2017. https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/131100_131199/131102/09.18.01_60/ts_131102v091801p.pdf.

- ↑ Munakata, M.; Schubert, S.; Ohba, T. (November 2006). RFC 4715: The Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN): Subaddress Encoding Type for tel URI. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC4715. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc4715.

- ↑ ""Charles Williams Jr. Part Two: Human Voice sent via Telegraph"". July 2010. http://www.telegraph-history.org/charles-williams-jr/part2.html.

- ↑ Fischer, Claude S. America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. Web.

- ↑ PhoneNumberGuy. http://phonenumberguy.com.

- ↑ International Correspondence Schools (1916). Subscribers' Station Equipment. International Library of Technology. Internal Textbook Company. p. 20. https://archive.org/details/electricityandm01schogoog. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Cuccia, Mark. "CODE 555 AND THE MOVIES". Telecom Heritage (Australian Telephone Collectors Society Inc.) (27). http://telephonecollecting.org/code.htm.

- ↑ de Vries, Lloyd (February 11, 2009). "'Almighty' Phone Mess". CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/almighty-phone-mess/.

- ↑ Silverman, Stephen M. (May 5, 2003). "'Bruce Almighty' delivers wrong number". http://www.people.com/people/article/0,,626175,00.html.

- ↑ Carlson Jen (2 July 2014). "The Oldest Phone Number In NYC" . Gothamist.

- ↑ "Old New York: Historical Attractions" . Hotel Pennsylvania. 23 January 2014. New York.

- ↑ Mikkelson, Barbara (9 July 2014). "867-5309 / Jenny". Snopes.com.

External links

- ITU-T Recommendation E.123: Notation for national and international telephone numbers, e-mail addresses and Web addresses

- RFC 3966 The

tel:URI for telephone numbers - History of UK dialing codes, with lists of codes and more links

- World Telephone Numbering Guide[Usurped!] which can be used to look up telephone numbering information

- ITU National Numbering Plans which links to the numbering plans of individual countries.

- Cybertelecom:: VoIP:: Numbers Detailing FCC policy regarding legacy NANP telephone numbers and interconnected VoIP services

- ATIS, Industry Numbering Committee

|

KSF

KSF