Tensor

From HandWiki - Reading time: 33 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 33 min

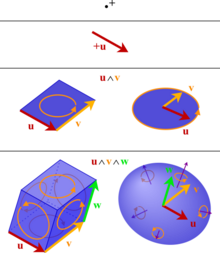

In mathematics, a tensor is an algebraic object that describes a multilinear relationship between sets of algebraic objects related to a vector space. Tensors may map between different objects such as vectors, scalars, and even other tensors. There are many types of tensors, including scalars and vectors (which are the simplest tensors), dual vectors, multilinear maps between vector spaces, and even some operations such as the dot product. Tensors are defined independent of any basis, although they are often referred to by their components in a basis related to a particular coordinate system; those components form an array, which can be thought of as a high-dimensional matrix.

Tensors have become important in physics because they provide a concise mathematical framework for formulating and solving physics problems in areas such as mechanics (stress, elasticity, fluid mechanics, moment of inertia, ...), electrodynamics (electromagnetic tensor, Maxwell tensor, permittivity, magnetic susceptibility, ...), general relativity (stress–energy tensor, curvature tensor, ...) and others. In applications, it is common to study situations in which a different tensor can occur at each point of an object; for example the stress within an object may vary from one location to another. This leads to the concept of a tensor field. In some areas, tensor fields are so ubiquitous that they are often simply called "tensors".

Tullio Levi-Civita and Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro popularised tensors in 1900 – continuing the earlier work of Bernhard Riemann, Elwin Bruno Christoffel, and others – as part of the absolute differential calculus. The concept enabled an alternative formulation of the intrinsic differential geometry of a manifold in the form of the Riemann curvature tensor.[1]

Definition

Although seemingly different, the various approaches to defining tensors describe the same geometric concept using different language and at different levels of abstraction.

As multidimensional arrays

A tensor may be represented as a (potentially multidimensional) array. Just as a vector in an n-dimensional space is represented by a one-dimensional array with n components with respect to a given basis, any tensor with respect to a basis is represented by a multidimensional array. For example, a linear operator is represented in a basis as a two-dimensional square n × n array. The numbers in the multidimensional array are known as the components of the tensor. They are denoted by indices giving their position in the array, as subscripts and superscripts, following the symbolic name of the tensor. For example, the components of an order 2 tensor T could be denoted Tij , where i and j are indices running from 1 to n, or also by T ij. Whether an index is displayed as a superscript or subscript depends on the transformation properties of the tensor, described below. Thus while Tij and T ij can both be expressed as n-by-n matrices, and are numerically related via index juggling, the difference in their transformation laws indicates it would be improper to add them together.

The total number of indices (m) required to identify each component uniquely is equal to the dimension or the number of ways of an array, which is why an array is sometimes referred to as an m-dimensional array or an m-way array. The total number of indices is also called the order, degree or rank of a tensor,[2][3][4] although the term "rank" generally has another meaning in the context of matrices and tensors.

Just as the components of a vector change when we change the basis of the vector space, the components of a tensor also change under such a transformation. Each type of tensor comes equipped with a transformation law that details how the components of the tensor respond to a change of basis. The components of a vector can respond in two distinct ways to a change of basis (see Covariance and contravariance of vectors), where the new basis vectors are expressed in terms of the old basis vectors as,

Here R ji are the entries of the change of basis matrix, and in the rightmost expression the summation sign was suppressed: this is the Einstein summation convention, which will be used throughout this article.[Note 1] The components vi of a column vector v transform with the inverse of the matrix R,

where the hat denotes the components in the new basis. This is called a contravariant transformation law, because the vector components transform by the inverse of the change of basis. In contrast, the components, wi, of a covector (or row vector), w, transform with the matrix R itself,

This is called a covariant transformation law, because the covector components transform by the same matrix as the change of basis matrix. The components of a more general tensor are transformed by some combination of covariant and contravariant transformations, with one transformation law for each index. If the transformation matrix of an index is the inverse matrix of the basis transformation, then the index is called contravariant and is conventionally denoted with an upper index (superscript). If the transformation matrix of an index is the basis transformation itself, then the index is called covariant and is denoted with a lower index (subscript).

As a simple example, the matrix of a linear operator with respect to a basis is a rectangular array that transforms under a change of basis matrix by . For the individual matrix entries, this transformation law has the form so the tensor corresponding to the matrix of a linear operator has one covariant and one contravariant index: it is of type (1,1).

Combinations of covariant and contravariant components with the same index allow us to express geometric invariants. For example, the fact that a vector is the same object in different coordinate systems can be captured by the following equations, using the formulas defined above:

- ,

where is the Kronecker delta, which functions similarly to the identity matrix, and has the effect of renaming indices (j into k in this example). This shows several features of the component notation: the ability to re-arrange terms at will (commutativity), the need to use different indices when working with multiple objects in the same expression, the ability to rename indices, and the manner in which contravariant and covariant tensors combine so that all instances of the transformation matrix and its inverse cancel, so that expressions like can immediately be seen to be geometrically identical in all coordinate systems.

Similarly, a linear operator, viewed as a geometric object, does not actually depend on a basis: it is just a linear map that accepts a vector as an argument and produces another vector. The transformation law for how the matrix of components of a linear operator changes with the basis is consistent with the transformation law for a contravariant vector, so that the action of a linear operator on a contravariant vector is represented in coordinates as the matrix product of their respective coordinate representations. That is, the components are given by . These components transform contravariantly, since

The transformation law for an order p + q tensor with p contravariant indices and q covariant indices is thus given as,

Here the primed indices denote components in the new coordinates, and the unprimed indices denote the components in the old coordinates. Such a tensor is said to be of order or type (p, q). The terms "order", "type", "rank", "valence", and "degree" are all sometimes used for the same concept. Here, the term "order" or "total order" will be used for the total dimension of the array (or its generalization in other definitions), p + q in the preceding example, and the term "type" for the pair giving the number of contravariant and covariant indices. A tensor of type (p, q) is also called a (p, q)-tensor for short.

This discussion motivates the following formal definition:[5][6]

Definition. A tensor of type (p, q) is an assignment of a multidimensional array

to each basis f = (e1, ..., en) of an n-dimensional vector space such that, if we apply the change of basis

then the multidimensional array obeys the transformation law

The definition of a tensor as a multidimensional array satisfying a transformation law traces back to the work of Ricci.[1]

An equivalent definition of a tensor uses the representations of the general linear group. There is an action of the general linear group on the set of all ordered bases of an n-dimensional vector space. If is an ordered basis, and is an invertible matrix, then the action is given by

Let F be the set of all ordered bases. Then F is a principal homogeneous space for GL(n). Let W be a vector space and let be a representation of GL(n) on W (that is, a group homomorphism ). Then a tensor of type is an equivariant map . Equivariance here means that

When is a tensor representation of the general linear group, this gives the usual definition of tensors as multidimensional arrays. This definition is often used to describe tensors on manifolds,[7] and readily generalizes to other groups.[5]

As multilinear maps

A downside to the definition of a tensor using the multidimensional array approach is that it is not apparent from the definition that the defined object is indeed basis independent, as is expected from an intrinsically geometric object. Although it is possible to show that transformation laws indeed ensure independence from the basis, sometimes a more intrinsic definition is preferred. One approach that is common in differential geometry is to define tensors relative to a fixed (finite-dimensional) vector space V, which is usually taken to be a particular vector space of some geometrical significance like the tangent space to a manifold.[8] In this approach, a type (p, q) tensor T is defined as a multilinear map,

where V∗ is the corresponding dual space of covectors, which is linear in each of its arguments. The above assumes V is a vector space over the real numbers, ℝ. More generally, V can be taken over any field F (e.g. the complex numbers), with F replacing ℝ as the codomain of the multilinear maps.

By applying a multilinear map T of type (p, q) to a basis {ej} for V and a canonical cobasis {εi} for V∗,

a (p + q)-dimensional array of components can be obtained. A different choice of basis will yield different components. But, because T is linear in all of its arguments, the components satisfy the tensor transformation law used in the multilinear array definition. The multidimensional array of components of T thus form a tensor according to that definition. Moreover, such an array can be realized as the components of some multilinear map T. This motivates viewing multilinear maps as the intrinsic objects underlying tensors.

In viewing a tensor as a multilinear map, it is conventional to identify the double dual V∗∗ of the vector space V, i.e., the space of linear functionals on the dual vector space V∗, with the vector space V. There is always a natural linear map from V to its double dual, given by evaluating a linear form in V∗ against a vector in V. This linear mapping is an isomorphism in finite dimensions, and it is often then expedient to identify V with its double dual.

Using tensor products

For some mathematical applications, a more abstract approach is sometimes useful. This can be achieved by defining tensors in terms of elements of tensor products of vector spaces, which in turn are defined through a universal property as explained here and here.

A type (p, q) tensor is defined in this context as an element of the tensor product of vector spaces,[9][10]

A basis vi of V and basis wj of W naturally induce a basis vi ⊗ wj of the tensor product V ⊗ W. The components of a tensor T are the coefficients of the tensor with respect to the basis obtained from a basis {ei} for V and its dual basis {εj}, i.e.

Using the properties of the tensor product, it can be shown that these components satisfy the transformation law for a type (p, q) tensor. Moreover, the universal property of the tensor product gives a one-to-one correspondence between tensors defined in this way and tensors defined as multilinear maps.

This 1 to 1 correspondence can be archived the following way, because in the finite dimensional case there exists a canonical isomorphism between a vectorspace and its double dual:

The last line is using the universal property of the tensor product, that there is a 1 to 1 correspondence between maps from and .[11]

Tensor products can be defined in great generality – for example, involving arbitrary modules over a ring. In principle, one could define a "tensor" simply to be an element of any tensor product. However, the mathematics literature usually reserves the term tensor for an element of a tensor product of any number of copies of a single vector space V and its dual, as above.

Tensors in infinite dimensions

This discussion of tensors so far assumes finite dimensionality of the spaces involved, where the spaces of tensors obtained by each of these constructions are naturally isomorphic.[Note 2] Constructions of spaces of tensors based on the tensor product and multilinear mappings can be generalized, essentially without modification, to vector bundles or coherent sheaves.[12] For infinite-dimensional vector spaces, inequivalent topologies lead to inequivalent notions of tensor, and these various isomorphisms may or may not hold depending on what exactly is meant by a tensor (see topological tensor product). In some applications, it is the tensor product of Hilbert spaces that is intended, whose properties are the most similar to the finite-dimensional case. A more modern view is that it is the tensors' structure as a symmetric monoidal category that encodes their most important properties, rather than the specific models of those categories.[13]

Tensor fields

In many applications, especially in differential geometry and physics, it is natural to consider a tensor with components that are functions of the point in a space. This was the setting of Ricci's original work. In modern mathematical terminology such an object is called a tensor field, often referred to simply as a tensor.[1]

In this context, a coordinate basis is often chosen for the tangent vector space. The transformation law may then be expressed in terms of partial derivatives of the coordinate functions,

defining a coordinate transformation,[1]

History

The concepts of later tensor analysis arose from the work of Carl Friedrich Gauss in differential geometry, and the formulation was much influenced by the theory of algebraic forms and invariants developed during the middle of the nineteenth century.[14] The word "tensor" itself was introduced in 1846 by William Rowan Hamilton[15] to describe something different from what is now meant by a tensor.[Note 3] Gibbs introduced Dyadics and Polyadic algebra, which are also tensors in the modern sense.[16] The contemporary usage was introduced by Woldemar Voigt in 1898.[17]

Tensor calculus was developed around 1890 by Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro under the title absolute differential calculus, and originally presented by Ricci-Curbastro in 1892.[18] It was made accessible to many mathematicians by the publication of Ricci-Curbastro and Tullio Levi-Civita's 1900 classic text Méthodes de calcul différentiel absolu et leurs applications (Methods of absolute differential calculus and their applications).[19] In Ricci's notation, he refers to "systems" with covariant and contravariant components, which are known as tensor fields in the modern sense. [16]

In the 20th century, the subject came to be known as tensor analysis, and achieved broader acceptance with the introduction of Einstein's theory of general relativity, around 1915. General relativity is formulated completely in the language of tensors. Einstein had learned about them, with great difficulty, from the geometer Marcel Grossmann.[20] Levi-Civita then initiated a correspondence with Einstein to correct mistakes Einstein had made in his use of tensor analysis. The correspondence lasted 1915–17, and was characterized by mutual respect:

I admire the elegance of your method of computation; it must be nice to ride through these fields upon the horse of true mathematics while the like of us have to make our way laboriously on foot.

— Albert Einstein[21]

Tensors were also found to be useful in other fields such as continuum mechanics. Some well-known examples of tensors in differential geometry are quadratic forms such as metric tensors, and the Riemann curvature tensor. The exterior algebra of Hermann Grassmann, from the middle of the nineteenth century, is itself a tensor theory, and highly geometric, but it was some time before it was seen, with the theory of differential forms, as naturally unified with tensor calculus. The work of Élie Cartan made differential forms one of the basic kinds of tensors used in mathematics, and Hassler Whitney popularized the tensor product. [16]

From about the 1920s onwards, it was realised that tensors play a basic role in algebraic topology (for example in the Künneth theorem).[22] Correspondingly there are types of tensors at work in many branches of abstract algebra, particularly in homological algebra and representation theory. Multilinear algebra can be developed in greater generality than for scalars coming from a field. For example, scalars can come from a ring. But the theory is then less geometric and computations more technical and less algorithmic.[23] Tensors are generalized within category theory by means of the concept of monoidal category, from the 1960s.[24]

Examples

An elementary example of a mapping describable as a tensor is the dot product, which maps two vectors to a scalar. A more complex example is the Cauchy stress tensor T, which takes a directional unit vector v as input and maps it to the stress vector T(v), which is the force (per unit area) exerted by material on the negative side of the plane orthogonal to v against the material on the positive side of the plane, thus expressing a relationship between these two vectors, shown in the figure (right). The cross product, where two vectors are mapped to a third one, is strictly speaking not a tensor because it changes its sign under those transformations that change the orientation of the coordinate system. The totally anti-symmetric symbol nevertheless allows a convenient handling of the cross product in equally oriented three dimensional coordinate systems.

This table shows important examples of tensors on vector spaces and tensor fields on manifolds. The tensors are classified according to their type (n, m), where n is the number of contravariant indices, m is the number of covariant indices, and n + m gives the total order of the tensor. For example, a bilinear form is the same thing as a (0, 2)-tensor; an inner product is an example of a (0, 2)-tensor, but not all (0, 2)-tensors are inner products. In the (0, M)-entry of the table, M denotes the dimensionality of the underlying vector space or manifold because for each dimension of the space, a separate index is needed to select that dimension to get a maximally covariant antisymmetric tensor.

| m | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ⋯ | M | ⋯ | ||

| n | 0 | Scalar, e.g. scalar curvature | Covector, linear functional, 1-form, e.g. dipole moment, gradient of a scalar field | Bilinear form, e.g. inner product, quadrupole moment, metric tensor, Ricci curvature, 2-form, symplectic form | 3-form E.g. octupole moment | E.g. M-form i.e. volume form | ||

| 1 | Euclidean vector | Linear transformation,[25] Kronecker delta | E.g. cross product in three dimensions | E.g. Riemann curvature tensor | ||||

| 2 | Inverse metric tensor, bivector, e.g., Poisson structure | E.g. elasticity tensor | ||||||

| ⋮ | ||||||||

| N | Multivector | |||||||

| ⋮ | ||||||||

Raising an index on an (n, m)-tensor produces an (n + 1, m − 1)-tensor; this corresponds to moving diagonally down and to the left on the table. Symmetrically, lowering an index corresponds to moving diagonally up and to the right on the table. Contraction of an upper with a lower index of an (n, m)-tensor produces an (n − 1, m − 1)-tensor; this corresponds to moving diagonally up and to the left on the table.

Properties

Assuming a basis of a real vector space, e.g., a coordinate frame in the ambient space, a tensor can be represented as an organized multidimensional array of numerical values with respect to this specific basis. Changing the basis transforms the values in the array in a characteristic way that allows to define tensors as objects adhering to this transformational behavior. For example, there are invariants of tensors that must be preserved under any change of the basis, thereby making only certain multidimensional arrays of numbers a tensor. Compare this to the array representing not being a tensor, for the sign change under transformations changing the orientation.

Because the components of vectors and their duals transform differently under the change of their dual bases, there is a covariant and/or contravariant transformation law that relates the arrays, which represent the tensor with respect to one basis and that with respect to the other one. The numbers of, respectively, vectors: n (contravariant indices) and dual vectors: m (covariant indices) in the input and output of a tensor determine the type (or valence) of the tensor, a pair of natural numbers (n, m), which determine the precise form of the transformation law. The order of a tensor is the sum of these two numbers.

The order (also degree or rank) of a tensor is thus the sum of the orders of its arguments plus the order of the resulting tensor. This is also the dimensionality of the array of numbers needed to represent the tensor with respect to a specific basis, or equivalently, the number of indices needed to label each component in that array. For example, in a fixed basis, a standard linear map that maps a vector to a vector, is represented by a matrix (a 2-dimensional array), and therefore is a 2nd-order tensor. A simple vector can be represented as a 1-dimensional array, and is therefore a 1st-order tensor. Scalars are simple numbers and are thus 0th-order tensors. This way the tensor representing the scalar product, taking two vectors and resulting in a scalar has order 2 + 0 = 2, the same as the stress tensor, taking one vector and returning another 1 + 1 = 2. The -symbol, mapping two vectors to one vector, would have order 2 + 1 = 3.

The collection of tensors on a vector space and its dual forms a tensor algebra, which allows products of arbitrary tensors. Simple applications of tensors of order 2, which can be represented as a square matrix, can be solved by clever arrangement of transposed vectors and by applying the rules of matrix multiplication, but the tensor product should not be confused with this.

Notation

There are several notational systems that are used to describe tensors and perform calculations involving them.

Ricci calculus

Ricci calculus is the modern formalism and notation for tensor indices: indicating inner and outer products, covariance and contravariance, summations of tensor components, symmetry and antisymmetry, and partial and covariant derivatives.

Einstein summation convention

The Einstein summation convention dispenses with writing summation signs, leaving the summation implicit. Any repeated index symbol is summed over: if the index i is used twice in a given term of a tensor expression, it means that the term is to be summed for all i. Several distinct pairs of indices may be summed this way.

Penrose graphical notation

Penrose graphical notation is a diagrammatic notation which replaces the symbols for tensors with shapes, and their indices by lines and curves. It is independent of basis elements, and requires no symbols for the indices.

Abstract index notation

The abstract index notation is a way to write tensors such that the indices are no longer thought of as numerical, but rather are indeterminates. This notation captures the expressiveness of indices and the basis-independence of index-free notation.

Component-free notation

A component-free treatment of tensors uses notation that emphasises that tensors do not rely on any basis, and is defined in terms of the tensor product of vector spaces.

Operations

There are several operations on tensors that again produce a tensor. The linear nature of tensor implies that two tensors of the same type may be added together, and that tensors may be multiplied by a scalar with results analogous to the scaling of a vector. On components, these operations are simply performed component-wise. These operations do not change the type of the tensor; but there are also operations that produce a tensor of different type.

Tensor product

The tensor product takes two tensors, S and T, and produces a new tensor, S ⊗ T, whose order is the sum of the orders of the original tensors. When described as multilinear maps, the tensor product simply multiplies the two tensors, i.e., which again produces a map that is linear in all its arguments. On components, the effect is to multiply the components of the two input tensors pairwise, i.e., If S is of type (l, k) and T is of type (n, m), then the tensor product S ⊗ T has type (l + n, k + m).

Contraction

Tensor contraction is an operation that reduces a type (n, m) tensor to a type (n − 1, m − 1) tensor, of which the trace is a special case. It thereby reduces the total order of a tensor by two. The operation is achieved by summing components for which one specified contravariant index is the same as one specified covariant index to produce a new component. Components for which those two indices are different are discarded. For example, a (1, 1)-tensor can be contracted to a scalar through . Where the summation is again implied. When the (1, 1)-tensor is interpreted as a linear map, this operation is known as the trace.

The contraction is often used in conjunction with the tensor product to contract an index from each tensor.

The contraction can also be understood using the definition of a tensor as an element of a tensor product of copies of the space V with the space V∗ by first decomposing the tensor into a linear combination of simple tensors, and then applying a factor from V∗ to a factor from V. For example, a tensor can be written as a linear combination

The contraction of T on the first and last slots is then the vector

In a vector space with an inner product (also known as a metric) g, the term contraction is used for removing two contravariant or two covariant indices by forming a trace with the metric tensor or its inverse. For example, a (2, 0)-tensor can be contracted to a scalar through (yet again assuming the summation convention).

Raising or lowering an index

When a vector space is equipped with a nondegenerate bilinear form (or metric tensor as it is often called in this context), operations can be defined that convert a contravariant (upper) index into a covariant (lower) index and vice versa. A metric tensor is a (symmetric) (0, 2)-tensor; it is thus possible to contract an upper index of a tensor with one of the lower indices of the metric tensor in the product. This produces a new tensor with the same index structure as the previous tensor, but with lower index generally shown in the same position of the contracted upper index. This operation is quite graphically known as lowering an index.

Conversely, the inverse operation can be defined, and is called raising an index. This is equivalent to a similar contraction on the product with a (2, 0)-tensor. This inverse metric tensor has components that are the matrix inverse of those of the metric tensor.

Applications

Continuum mechanics

Important examples are provided by continuum mechanics. The stresses inside a solid body or fluid[28] are described by a tensor field. The stress tensor and strain tensor are both second-order tensor fields, and are related in a general linear elastic material by a fourth-order elasticity tensor field. In detail, the tensor quantifying stress in a 3-dimensional solid object has components that can be conveniently represented as a 3 × 3 array. The three faces of a cube-shaped infinitesimal volume segment of the solid are each subject to some given force. The force's vector components are also three in number. Thus, 3 × 3, or 9 components are required to describe the stress at this cube-shaped infinitesimal segment. Within the bounds of this solid is a whole mass of varying stress quantities, each requiring 9 quantities to describe. Thus, a second-order tensor is needed.

If a particular surface element inside the material is singled out, the material on one side of the surface will apply a force on the other side. In general, this force will not be orthogonal to the surface, but it will depend on the orientation of the surface in a linear manner. This is described by a tensor of type (2, 0), in linear elasticity, or more precisely by a tensor field of type (2, 0), since the stresses may vary from point to point.

Other examples from physics

Common applications include:

- Electromagnetic tensor (or Faraday tensor) in electromagnetism

- Finite deformation tensors for describing deformations and strain tensor for strain in continuum mechanics

- Permittivity and electric susceptibility are tensors in anisotropic media

- Four-tensors in general relativity (e.g. stress–energy tensor), used to represent momentum fluxes

- Spherical tensor operators are the eigenfunctions of the quantum angular momentum operator in spherical coordinates

- Diffusion tensors, the basis of diffusion tensor imaging, represent rates of diffusion in biological environments

- Quantum mechanics and quantum computing utilize tensor products for combination of quantum states

Computer vision and optics

The concept of a tensor of order two is often conflated with that of a matrix. Tensors of higher order do however capture ideas important in science and engineering, as has been shown successively in numerous areas as they develop. This happens, for instance, in the field of computer vision, with the trifocal tensor generalizing the fundamental matrix.

The field of nonlinear optics studies the changes to material polarization density under extreme electric fields. The polarization waves generated are related to the generating electric fields through the nonlinear susceptibility tensor. If the polarization P is not linearly proportional to the electric field E, the medium is termed nonlinear. To a good approximation (for sufficiently weak fields, assuming no permanent dipole moments are present), P is given by a Taylor series in E whose coefficients are the nonlinear susceptibilities:

Here is the linear susceptibility, gives the Pockels effect and second harmonic generation, and gives the Kerr effect. This expansion shows the way higher-order tensors arise naturally in the subject matter.

Machine learning

The properties of Tensors (machine learning), especially tensor decomposition, have enabled their use in machine learning to embed higher dimensional data in artificial neural networks.

Generalizations

Tensor products of vector spaces

The vector spaces of a tensor product need not be the same, and sometimes the elements of such a more general tensor product are called "tensors". For example, an element of the tensor product space V ⊗ W is a second-order "tensor" in this more general sense,Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Another way of generalizing the idea of tensor, common in nonlinear analysis, is via the multilinear maps definition where instead of using finite-dimensional vector spaces and their algebraic duals, one uses infinite-dimensional Banach spaces and their continuous dual.[29] Tensors thus live naturally on Banach manifolds[30] and Fréchet manifolds.

Tensor densities

Suppose that a homogeneous medium fills R3, so that the density of the medium is described by a single scalar value ρ in kg⋅m−3. The mass, in kg, of a region Ω is obtained by multiplying ρ by the volume of the region Ω, or equivalently integrating the constant ρ over the region:

where the Cartesian coordinates x, y, z are measured in m. If the units of length are changed into cm, then the numerical values of the coordinate functions must be rescaled by a factor of 100:

The numerical value of the density ρ must then also transform by 100−3 m3/cm3 to compensate, so that the numerical value of the mass in kg is still given by integral of . Thus (in units of kg⋅cm−3).

More generally, if the Cartesian coordinates x, y, z undergo a linear transformation, then the numerical value of the density ρ must change by a factor of the reciprocal of the absolute value of the determinant of the coordinate transformation, so that the integral remains invariant, by the change of variables formula for integration. Such a quantity that scales by the reciprocal of the absolute value of the determinant of the coordinate transition map is called a scalar density. To model a non-constant density, ρ is a function of the variables x, y, z (a scalar field), and under a curvilinear change of coordinates, it transforms by the reciprocal of the Jacobian of the coordinate change. For more on the intrinsic meaning, see Density on a manifold.

A tensor density transforms like a tensor under a coordinate change, except that it in addition picks up a factor of the absolute value of the determinant of the coordinate transition:[31]

Here w is called the weight. In general, any tensor multiplied by a power of this function or its absolute value is called a tensor density, or a weighted tensor.[32][33] An example of a tensor density is the current density of electromagnetism.

Under an affine transformation of the coordinates, a tensor transforms by the linear part of the transformation itself (or its inverse) on each index. These come from the rational representations of the general linear group. But this is not quite the most general linear transformation law that such an object may have: tensor densities are non-rational, but are still semisimple representations. A further class of transformations come from the logarithmic representation of the general linear group, a reducible but not semisimple representation,[34] consisting of an (x, y) ∈ R2 with the transformation law

Geometric objects

The transformation law for a tensor behaves as a functor on the category of admissible coordinate systems, under general linear transformations (or, other transformations within some class, such as local diffeomorphisms). This makes a tensor a special case of a geometrical object, in the technical sense that it is a function of the coordinate system transforming functorially under coordinate changes.[35] Examples of objects obeying more general kinds of transformation laws are jets and, more generally still, natural bundles.[36][37]

Spinors

When changing from one orthonormal basis (called a frame) to another by a rotation, the components of a tensor transform by that same rotation. This transformation does not depend on the path taken through the space of frames. However, the space of frames is not simply connected (see orientation entanglement and plate trick): there are continuous paths in the space of frames with the same beginning and ending configurations that are not deformable one into the other. It is possible to attach an additional discrete invariant to each frame that incorporates this path dependence, and which turns out (locally) to have values of ±1.[38] A spinor is an object that transforms like a tensor under rotations in the frame, apart from a possible sign that is determined by the value of this discrete invariant.[39][40]

Succinctly, spinors are elements of the spin representation of the rotation group, while tensors are elements of its tensor representations. Other classical groups have tensor representations, and so also tensors that are compatible with the group, but all non-compact classical groups have infinite-dimensional unitary representations as well.

See also

- Array data type, for tensor storage and manipulation

Foundational

Applications

- Application of tensor theory in engineering

- Continuum mechanics

- Covariant derivative

- Curvature

- Diffusion tensor MRI

- Einstein field equations

- Fluid mechanics

- Gravity

- Multilinear subspace learning

- Riemannian geometry

- Structure tensor

- Tensor Contraction Engine

- Tensor decomposition

- Tensor derivative

- Tensor software

Explanatory notes

- ↑ The Einstein summation convention, in brief, requires the sum to be taken over all values of the index whenever the same symbol appears as a subscript and superscript in the same term. For example, under this convention

- ↑ The double duality isomorphism, for instance, is used to identify V with the double dual space V∗∗, which consists of multilinear forms of degree one on V∗. It is typical in linear algebra to identify spaces that are naturally isomorphic, treating them as the same space.

- ↑ Namely, the norm operation in a vector space.

References

Specific

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kline, Morris (1990). Mathematical Thought From Ancient to Modern Times. 3. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506137-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=-OsRDAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ De Lathauwer, Lieven; De Moor, Bart; Vandewalle, Joos (2000). "A Multilinear Singular Value Decomposition". SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 21 (4): 1253–1278. doi:10.1137/S0895479896305696. https://alterlab.org/teaching/BME6780/papers+patents/De_Lathauwer_2000.pdf.

- ↑ Vasilescu, M.A.O.; Terzopoulos, D. (2002). "Multilinear Analysis of Image Ensembles: TensorFaces". Computer Vision — ECCV 2002. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2350. pp. 447–460. doi:10.1007/3-540-47969-4_30. ISBN 978-3-540-43745-1. http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~maov/tensorfaces/Springer%20ECCV%202002_files/eccv02proceeding_23500447.pdf.

- ↑ Kolda, Tamara; Bader, Brett (2009). "Tensor Decompositions and Applications". SIAM Review 51 (3): 455–500. doi:10.1137/07070111X. Bibcode: 2009SIAMR..51..455K. https://www.kolda.net/publication/TensorReview.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sharpe, R.W. (2000). Differential Geometry: Cartan's Generalization of Klein's Erlangen Program. Springer. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-387-94732-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ytqs4xU5QKAC&pg=PA194.

- ↑ Schouten, Jan Arnoldus (1954), "Chapter II", Tensor analysis for physicists, Courier Corporation, ISBN 978-0-486-65582-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=WROiC9st58gC

- ↑ Kobayashi, Shoshichi; Nomizu, Katsumi (1996), Foundations of Differential Geometry, 1 (New ed.), Wiley Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-15733-5

- ↑ Lee, John (2000), Introduction to smooth manifolds, Springer, p. 173, ISBN 978-0-387-95495-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=4sGuQgAACAAJ&pg=PA173

- ↑ Dodson, C.T.J.; Poston, T. (2013). Tensor geometry: The Geometric Viewpoint and Its Uses. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 130 (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 105. ISBN 9783642105142.

- ↑ Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Affine tensor", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=a/a011120

- ↑ "Why are Tensors (Vectors of the form a⊗b...⊗z) multilinear maps?". June 5, 2021. https://math.stackexchange.com/q/4163471.

- ↑ Bourbaki, N. (1998). "3". Algebra I: Chapters 1-3. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-64243-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=STS9aZ6F204C. where the case of finitely generated projective modules is treated. The global sections of sections of a vector bundle over a compact space form a projective module over the ring of smooth functions. All statements for coherent sheaves are true locally.

- ↑ Joyal, André; Street, Ross (1993), "Braided tensor categories", Advances in Mathematics 102: 20–78, doi:10.1006/aima.1993.1055

- ↑ Reich, Karin (1994). Die Entwicklung des Tensorkalküls. Science networks historical studies. 11. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-7643-2814-6. OCLC 31468174. https://books.google.com/books?id=O6lixBzbc0gC.

- ↑ Hamilton, William Rowan (1854–1855). Wilkins, David R.. ed. "On some Extensions of Quaternions". Philosophical Magazine (7–9): 492–9, 125–137, 261–9, 46–51, 280–290. ISSN 0302-7597. http://www.emis.de/classics/Hamilton/ExtQuat.pdf. From p. 498: "And if we agree to call the square root (taken with a suitable sign) of this scalar product of two conjugate polynomes, P and KP, the common TENSOR of each, … "

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Guo, Hongyu (2021-06-16) (in en). What Are Tensors Exactly?. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-12-4103-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5dM3EAAAQBAJ&q=array+vector+matrix+tensor.

- ↑ Voigt, Woldemar (1898). Die fundamentalen physikalischen Eigenschaften der Krystalle in elementarer Darstellung. Von Veit. pp. 20–. https://books.google.com/books?id=QhBDAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA20. "Wir wollen uns deshalb nur darauf stützen, dass Zustände der geschilderten Art bei Spannungen und Dehnungen nicht starrer Körper auftreten, und sie deshalb tensorielle, die für sie charakteristischen physikalischen Grössen aber Tensoren nennen. [We therefore want [our presentation] to be based only on [the assumption that] conditions of the type described occur during stresses and strains of non-rigid bodies, and therefore call them "tensorial" but call the characteristic physical quantities for them "tensors".]"

- ↑ Ricci Curbastro, G. (1892). "Résumé de quelques travaux sur les systèmes variables de fonctions associés à une forme différentielle quadratique". Bulletin des Sciences Mathématiques 2 (16): 167–189. https://books.google.com/books?id=1bGdAQAACAAJ.

- ↑ Ricci & Levi-Civita 1900.

- ↑ Pais, Abraham (2005). Subtle Is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280672-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=U2mO4nUunuwC.

- ↑ "The Italian Mathematicians of Relativity". Centaurus 26 (3): 241–261. 1982. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1982.tb00665.x. Bibcode: 1982Cent...26..241G.

- ↑ Spanier, Edwin H. (2012). Algebraic Topology. Springer. pp. 227. ISBN 978-1-4684-9322-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=iKx3BQAAQBAJ&&pg=PA227. "the Künneth formula expressing the homology of the tensor product..."

- ↑ Hungerford, Thomas W. (2003). Algebra. Springer. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-387-90518-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=t6N_tOQhafoC&pg=PA168. "...the classification (up to isomorphism) of modules over an arbitrary ring is quite difficult..."

- ↑ MacLane, Saunders (2013). Categories for the Working Mathematician. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4612-9839-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=6KPSBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA4. "...for example the monoid M ... in the category of abelian groups, × is replaced by the usual tensor product..."

- ↑ Bamberg, Paul; Sternberg, Shlomo (1991). A Course in Mathematics for Students of Physics. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 669. ISBN 978-0-521-40650-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=WgZ3Ia0SPE8CA.

- ↑ Penrose, R. (2007). The Road to Reality. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-77631-4.

- ↑ Wheeler, J.A.; Misner, C.; Thorne, K.S. (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=w4Gigq3tY1kC.

- ↑ Schobeiri, Meinhard T. (2021). "Vector and Tensor Analysis, Applications to Fluid Mechanics". Fluid Mechanics for Engineers. Springer. pp. 11–29.

- ↑ Abraham, Ralph; Marsden, Jerrold E.; Ratiu, Tudor S. (February 1988). "5. Tensors". Manifolds, Tensor Analysis and Applications. Applied Mathematical Sciences. 75 (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 338–9. ISBN 978-0-387-96790-5. OCLC 18562688. https://books.google.com/books?id=dWHet_zgyCAC. "Elements of Trs are called tensors on E, [...]."

- ↑ Lang, Serge (1972). Differential manifolds. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-04166-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=dn7rBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Schouten, Jan Arnoldus, "§II.8: Densities", Tensor analysis for physicists, https://books.google.com/books?id=WROiC9st58gC

- ↑ McConnell, A.J. (2014). Applications of tensor analysis. Dover. p. 28. ISBN 9780486145020. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZCP0AwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Kay 1988, p. 27.

- ↑ Olver, Peter (1995), Equivalence, invariants, and symmetry, Cambridge University Press, p. 77, ISBN 9780521478113, https://books.google.com/books?id=YuTzf61HILAC&pg=PA77

- ↑ Haantjes, J.; Laman, G. (1953). "On the definition of geometric objects. I". Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen: Series A: Mathematical Sciences 56 (3): 208–215.

- ↑ Nijenhuis, Albert (1960), "Geometric aspects of formal differential operations on tensor fields", Proc. Internat. Congress Math.(Edinburgh, 1958), Cambridge University Press, pp. 463–9, http://www.mathunion.org/ICM/ICM1958/Main/icm1958.0463.0469.ocr.pdf, retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ Salviori, Sarah (1972), "On the theory of geometric objects", Journal of Differential Geometry 7 (1–2): 257–278, doi:10.4310/jdg/1214430830, https://projecteuclid.org/download/pdf_1/euclid.jdg/1214430830.

- ↑ Penrose, Roger (2005). The road to reality: a complete guide to the laws of our universe. Knopf. pp. 203–206. https://books.google.com/books?id=VWTNCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA203.

- ↑ Meinrenken, E. (2013). "The spin representation". Clifford Algebras and Lie Theory. Ergebnisse der Mathematik undihrer Grenzgebiete. 3. Folge / A Series of Modern Surveys in Mathematics. 58. Springer. pp. 49–85. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36216-3_3. ISBN 978-3-642-36215-6.

- ↑ Dong, S. H. (2011), "2. Special Orthogonal Group SO(N)", Wave Equations in Higher Dimensions, Springer, pp. 13–38

General

- Bishop; Samuel I. Goldberg (1980). Tensor Analysis on Manifolds. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-64039-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=ePFIAwAAQBAJ.

- Danielson, Donald A. (2003). Vectors and Tensors in Engineering and Physics (2/e ed.). Westview (Perseus). ISBN 978-0-8133-4080-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=A9fiXTC3cxsC.

- Dimitrienko, Yuriy (2002). Tensor Analysis and Nonlinear Tensor Functions. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-1015-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=7UMYToTiYDsC.

- Jeevanjee, Nadir (2011). An Introduction to Tensors and Group Theory for Physicists. Birkhauser. ISBN 978-0-8176-4714-8. https://www.springer.com/new+%26+forthcoming+titles+(default)/book/978-0-8176-4714-8.

- Lawden, D. F. (2003). Introduction to Tensor Calculus, Relativity and Cosmology (3/e ed.). Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-42540-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=rJYoAwAAQBAJ.

- Lebedev, Leonid P.; Cloud, Michael J. (2003). Tensor Analysis. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-360-0.

- Lovelock, David; Rund, Hanno (1989). Tensors, Differential Forms, and Variational Principles. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-65840-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=Tl3dCgAAQBAJ.

- Munkres, James R. (1997). Analysis On Manifolds. Avalon. ISBN 978-0-8133-4548-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=tGT6K6HdFfwC. Chapter six gives a "from scratch" introduction to covariant tensors.

- Ricci, Gregorio; Levi-Civita, Tullio (March 1900). "Méthodes de calcul différentiel absolu et leurs applications". Mathematische Annalen 54 (1–2): 125–201. doi:10.1007/BF01454201. https://zenodo.org/record/1428270.

- Kay, David C (1988-04-01). Schaum's Outline of Tensor Calculus. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-033484-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=6tUU3KruG14C.

- Schutz, Bernard F. (28 January 1980). Geometrical Methods of Mathematical Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29887-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=HAPMB2e643kC.

- Synge, John Lighton; Schild, Alfred (1969). Tensor Calculus. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-63612-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=8vlGhlxqZjsC.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Tensor". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Tensor.html.

- Bowen, Ray M.; Wang, C.C. (1976). Linear and Multilinear Algebra. Introduction to Vectors and Tensors. 1. Plenum Press. ISBN 9780306375088.

- Bowen, Ray M.; Wang, C.C. (2006). Vector and Tensor Analysis. Introduction to Vectors and Tensors. 2. ISBN 9780306375095.

- Kolecki, Joseph C. (2002). "An Introduction to Tensors for Students of Physics and Engineering". Cleveland, Ohio: NASA Glenn Research Center. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20020083040.

- Kolecki, Joseph C. (2005). "Foundations of Tensor Analysis for Students of Physics and Engineering With an Introduction to the Theory of Relativity". Cleveland, Ohio: NASA Glenn Research Center. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20050175884.pdf.

- A discussion of the various approaches to teaching tensors, and recommendations of textbooks

- Sharipov, Ruslan (2004). "Quick introduction to tensor analysis". arXiv:math.HO/0403252.

- Feynman, Richard (1964–2013). "31. Tensors". The Feynman Lectures. California Institute of Technology. https://feynmanlectures.caltech.edu/II_31.html.

|

KSF

KSF