Thames school of chartmakers

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

The Thames school of chartmakers was a small group of English nautical chartmakers who plied their trade in streets and alleys leading down to the waterfront on the north Bank of the Thames, east of the Tower of London.[1] Active between 1590 and 1740,[2] they were critically involved in England's maritime affairs, yet the school was not identified by modern scholars until 1959.[3][4]

"At the Signe of the Platt"

Its existence was revealed by Spanish historian of science Ernesto García Camarero,[3][4] who examined a number of 17th-century English charts and noticed some common features. He described them as portolan charts with windrose networks (see illustration). They bore the legend "at the Signe of the Platt" with addresses[5] in or near the Port of London. They were hand-drawn on vellum, pasted to four hinged rectangular boards. They did not employ Mercator's projection — conservative English seamen did not trust this innovation[6] — but they were corrected for magnetic declination. No attempt was made to show inland features such as rivers or mountains, nor political or human symbols.[7] They had (wrote García Camarero) a certain unfussy unity of style:

"The design of the mapping closely followed the traditional Mediterranean form; but whereas an overripe Baroque has infected the latter, the English school, by its restraint, manages to reinvigorate the decadent portolan. The windrose and some compass roses are conserved; coastlines are finely traced; islands and coasts are illuminated in soft colours; placenames are rendered in characteristic lettering; in small places (e.g. islands) they are replaced by numbers, with tables of equivalents placed in the margins or blank spaces."[8]

The word platt (a variant of plot) meant a chart. "The signe of the platt" was a signboard that hung outside a chartmaker's shop.[9] University of Kansas scholar Thomas R. Smith discovered a number of these men were members of the Drapers' Company,[10] a guild of the City of London, and from its records he[11] and Tony Campbell[12] derived trees of master-and-apprentice relations spanning 125 years.

One particular chain of teaching was John Daniell → Nicholas Comberford → John Burston → John Thornton → Joel Gascoyne, all of whom were important enough to have left charts that survive today, a rare thing for the period.[13]

Significance

The English came late to the art of oceanic navigation, the rudiments of which they learned from the Portuguese and (especially during the marriage of Mary Tudor and Philip II of Spain) the Spanish [14] Their charts were lacking and they needed to catch up.[15]

Faced with new discoveries, the Portuguese and Spanish governments attempted to institutionalise their cartography by setting up state controlled houses. The Casa da Mina (in Lisbon) and the Casa de Contratación (in Seville) had hydrographic offices that were ordered to build up gigantic, secret, master charts: the first maps of empire. Astronomers and other experts were set to work. The two casas were Europe's first scientific institutions. A key purpose was to standardise knowledge "so that errors and inconsistencies among charts could be eliminated and they could be revised and updated as new discoveries were made".[16]

The task — coordinating local observations into a coherent knowledge space — turned out to be too difficult for the science of the day, and was gradually abandoned.[17] Nevertheless the two Iberian powers held funds of local knowhow far exceeding that available to others.

David W. Waters said that

as late as 1568 probably only one English seaman was capable of navigating to the West Indies without the aid of Portuguese, French or Spanish pilots. Yet, by the time of the Armada, a mere score of years later, Englishmen had gained a "reputation of being above all Western nations, expert and active in all naval operations".[18]

By 1640 the English had charted all the world's known seas and coasts and were self-sufficient.[19]

It was the business of the Thames chartmakers to make charts with useful information, and this was obtained from any available source including espionage.[20] Unlike the Stationers' Guild (who had a monopoly of printing and applied a common law of copyright),[21] in the Drapers Company copying was commonplace.[22]

There is some evidence that chartmaking was not a lucrative occupation.[23] The best published charts were Dutch, so these were heavily copied.[24][25][26][27] However, few good Dutch charts of North America could be obtained, so the Thames chartmakers were obliged and stimulated to evolve original works: "The English made maps because they had to", wrote Jeanette D. Black.[28]

Likewise for voyages to find the Northwest or Northeast Passage, or to Guiana or the Amazon basin.[19] Prior to any of these was England's first maritime discovery, the White Sea route to Russia.[29] In time, English chartmamers came to be dominant as the Dutch had been.[30][31]

One assessment:

Ultimately, England's commercial and imperial ventures could not have succeeded without an English charting tradition. The charts of the Thames School reflect the breadth of English overseas interests.[32]

Thames school charts

"Beautiful to the modern eye", wrote Alaistair Maeer, and made with colourful scales and intricate compass roses, in other respects early Thames school charts were plain and unadorned, concentrating on the practical business of navigating. In sharp contrast to their Continental counterparts, they did not depict missionaries, "heraldic markers, animals, trees, local inhabitants, and villages".[33] For Maeer, the contrast was striking, and his explanation was that the Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch charts of the era were produced at the behest of state-sponsored institutions[34] who routinely projected religious or political symbols asserting dominion and mastery. The Thames school charts, however, were not a product of government oversight; and imperial aggrandisement was not yet a motivation for English voyagers, who saw the world in terms of opportunities for buying and selling.[35]

- Nicholas Comberford, Irishman, of "neare unto the West Ende of the Schoole House in Radecliff". An early member of the Thames school, he was bound apprentice to its founder, John Daniell, in 1612. (Bodleian Libraries.)

- John Burston, of Ratcliff Highway, (National Maritime Museum). Bound apprentice to Nicholas Comberford, 1628.

- Andrew Welch, North Atlantic (National Maritime Museum). "At the Signe of the Platt neare Ratcliff Highway", apprenticed to Comberford, 1649. Notice the hingeline.

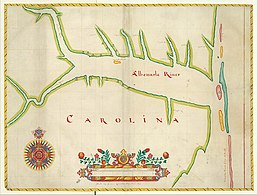

- James Lancaster, Albemarle Sound, Carolina; believed to be his only surviving chart (John Carter Brown Library). Apprenticed to Burston, 1656.

- Augustine Fitzhugh, a draft of Boston Harbor (Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center). Apprenticed to Thornton, 1675.[36]

Later, as England came into conflict with other European powers, imperial rivalries developed. These were reflected in the style of the later Thames school. "English charting began to exhibit dominion and empire, thereby mirroring Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch charts".[37]

- New York. A description of the Towne of Mannado or New Amsterdam (1664). Described as New York's birth certificate, it was made for the Duke of York (James II) as the town was passing to English rule. The vertical feature will become Wall Street; on the right is The Battery. By an unknown member of the Thames school. (British Library.)

- The Port of Arica, present-day Chile, Spanish entrepot for the great mine of Potosí, whence came half the world's silver output. It got attention from pirates, accordingly. Based on a Spanish derrotero captured by English pirate Bartholomew Sharp, who escaped a criminal conviction in England by agreeing to cooperate with the government. Under conditions of uttermost secrecy[38] this chart was drawn by William Hack of the Thames school. (National Maritime Museum.)

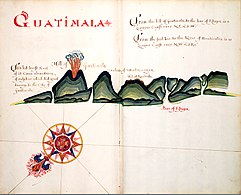

- Guatemala. "The hill burst & of it Came aboundance of sulphur which did great damage to the Citty of Guatimala" (eruption of the volcano Pacaya). Based on the same captured Spanish chartbook. (National Maritime Museum.)

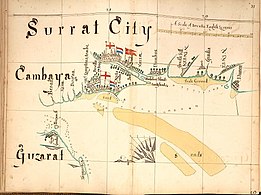

- Surat City in the Gujarat. Notice the flags of the English, Dutch and Portuguese factories. (Library of Congress.)

- South China Sea. A finely detailed coastal chart with Formosa (Taiwan) and Zhejiang, China. Once again Hack uses his trademark one-quarter compass rose. (Library of Congress.)

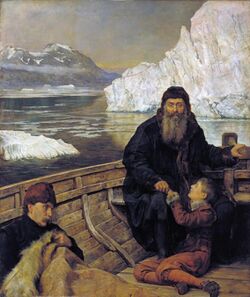

John Thornton

Thornton, "the most competent and distinguished chart-maker in England"[1] was also a surveyor and an engraver. So far as is known, it was in England a unique combination of skills.[39]

Thornton worked in the Minories just outside the City limits. He was hydrographer to the East India Company and the Hudson's Bay Company; Monique de la Roncière called him "the celebrated English hydrographer".[40]

Part of John Thornton's output was hand-drawn. Charts, in the hands of seamen, wore out in use[41] or, becoming obsolete, were cannibalised for the sake of the vellum.[42] Probably, most existing Thornton specimens would have perished had not French privateers captured an East Indiaman with her complement of charts: they were preserved for posterity in the Service Hydrographique de la Marine.[25]

Because Thornton was also an engraver, however, a good part of his surviving output was printed,[43] despite the Stationers' legal monopoly. Printing was done from engraved copper plates, an art he taught to Joel Gascoyne. It was seldom undertaken except for long print runs, because engraved copper plates were expensive to make.[44] According to de la Roncière, Thornton made notable contributions, "above all The English Pilot The Third Book describing the sea coasts. . . in the Oriental Navigation, a precious collection of thirty-five charts with sailing-directions"[43]

Joel Gascoyne

Joel Gascoyne (1650-1704) after completing his apprenticeship with Thornton set up in business at "Ye Signe of ye Platt neare Wapping Old Stayres" and became a famous maker of manuscript and engraved charts, later changing careers to become one of the leading surveyors of his day and setting new standards for accuracy.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ravenhill & Johnson 1995, p. 1.

- ↑ Maeer 2020, p. 68.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Campbell 1973, p. 81.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Smith 1978, p. 52.

- ↑ Contrary to Smith 1978, p. 53, García Camarero did not interpret the phrase as "as an indication of collaboration at a single address", explicitly stating otherwise.

- ↑ Tyacke 1987, p. 1744.

- ↑ García Camarero 1959, pp. 65-68.

- ↑ García Camarero 1959, p. 67(Wikipedia translation)

- ↑ Smith 1978, p. 53.

- ↑ The Drapers' Company, at first a powerful guild of wool and cloth merchants, came to accept members who were not even slightly connected with cloth, and these included the chartmakers: Smith 1978, p. 56

- ↑ Smith 1978, p. 97.

- ↑ Campbell 1973, p. 100.

- ↑ Smith 1978, pp. 52-55.

- ↑ Waters 1970, pp. 1-19, esp. 14-15.

- ↑ Tyacke 1987, pp. 1722, 1725, 1727, 1729, 1731.

- ↑ Turnbull 1996, p. 7.

- ↑ Turnbull 1996, pp. 9-14.

- ↑ David W. Waters, The Art of Navigation in Elizabethan and Early Stuart Times, quoted in Smith 1978, pp. 49–50. The words in quotes are those of a Venetian ambassador to France.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Tyacke 1987, p. 1731.

- ↑ Tyacke 1987, pp. 1723, 1726, 1730, 1731.

- ↑ Laddie, Prescott & Vitoria 2018, pp. 5-10, 369.

- ↑ Tyacke 1987, pp. 1730-1.

- ↑ According to one casual visitor's anecdote, the chartmaker Nicholas Comberford lived in squalor and claimed it took him three weeks to make a chart for which he wanted 25 shillings: Smith 1978, pp. 91–2 (worth about $420 US today).

- ↑ Verner 1978, p. 127.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Roncière 1965, p. 47.

- ↑ Macey 1979, pp. 530, 533.

- ↑ Black 1978, pp. 102-3.

- ↑ Black 1978, pp. 103-4, 123.

- ↑ Maeer 2012, pp. 23-24, 32-35.

- ↑ Verner 1978, pp. 156-7.

- ↑ Maeer 2012, p. 29.

- ↑ Maeer 2012, p. 34.

- ↑ Maeer 2020, p. 73.

- ↑ In the Netherlands, state-sponsored trading corporations such as the Dutch East India Company.

- ↑ Maeer 2020, pp. 67, 70, 72, 81, 89.

- ↑ Data in Smith 1978, p. 97

- ↑ Maeer 2020, pp. 67-8.

- ↑ Kelly 2004.

- ↑ Ravenhill 1972b, p. 60.

- ↑ Roncière 1965, pp. 46, 47.

- ↑ Smith 1978, p. 95.

- ↑ Tyacke 1987, pp. 1731-2.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Roncière 1965, p. 46.

- ↑ Woodward 1978, p. 164-6.

Sources

- Black, Jeanette D. (1978). "Mapping the English Colonies in North America: the Beginnings". in Thrower, Norman J.W.. The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

- Campbell, Tony (1973). "The Drapers' Company and Its School of Seventeenth Century Chart-Makers". in Wallis, Helen; Tyacke, Sarah. My Head Is a Map: a Festschrift for R. V. Tooley. London: Francis Edwards and Carta Press.

- García Camarero, Ernesto (1959). "La Escuela cartográfica inglesa "At the Signe of the Platt"" (in es). Boletín de la Real Sociedad Geográfica (Madrid) XCV (1–6): 65–68. https://realsociedadgeografica.com/boletines/Tomo%20XCV%20-%201959.pdf.

- Kelly, James William (2004). "Hack William (fl. 1670-1702)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

- Laddie; Prescott; Vitoria (2018). The Modern Law of Copyright. I (5 ed.). LexisNexis Butterworths. ISBN 9781474306898.

- Maeer, Alaistair (2012). "The Baltic and the birth of a modern English maritime community: the Muscovy Company and nautical cartography, 1553-1665". Revista Română de Studii Baltice și Nordice 4 (2): 19–49. doi:10.53604/rjbns.v4i2_2. ISSN 2067-1725. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338084631. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Maeer, Alaistair S. (2020). "The cartography of the sea. Mapping England's 'mastery of the oceans'". in Jowitt, Claire; Lambert, Craig; Mentz, Steve. The Routledge Companion to Marine and Maritime Worlds 1400-1800. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781003048503. https://books.google.com/books?id=13jnDwAAQBAJ&q=%22interlocking+rhumb+lines%22&pg=PT80. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Macey, Samuel L. (1979). "Review: The Compleat Plattmaker: British Chart and Map Making, 1650-1750". Eighteenth-Century Studies (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 12 (4): 527–537. doi:10.2307/2738459.

- Ravenhill, William (1972b). "Joel Gascoyne, a Pioneer of Large-Scale County Mapping". Imago Mundi (Imago Mundi, Ltd) 26: 60–70. doi:10.1080/03085697208592391.

- Ravenhill, W. L. D.; Johnson, David J. (1995). Saunders, Ann. ed. Joel Gascoyne's engraved maps of Stepney, 1702-04. Publication / London Topographical Society ;150. London: London Topographical Society, in association with Guildhall Library. ISBN 9780902087361. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/inu.30000044867095. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- Roncière, Monique de la (1965). "Manuscript Charts by John Thornton, Hydrographer of the East India Company (1669- 1701)". Imago Mundi 19: 46–50. doi:10.1080/03085696508592265.

- Smith, Thomas R. (1978). "Manuscripts and Printed Sea Charts in Seventeenth-Century London: The Case of the Thames School". in Thrower, Norman J.W.. The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

- Turnbull, David (1996). "Cartography and Science in Early Modern Europe: Mapping the Construction of Knowledge Spaces". Imago Mundi 48: 5–24. doi:10.1080/03085699608592830.

- Tyacke, Sarah (1987). "58 • Chartmaking in England and Its Context, 1500—1660". in Harley, J.B.; Woodward, David. The History of cartography. 3. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1722–1753. https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V3_Pt2/HOC_VOLUME3_Part2_chapter58.pdf.

- Verner, Coolie (1978). "John Seller and the Chart Trade in Seventeenth-Century England". in Thrower, Norman J.W.. The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

- Waters, David (1970). "The Iberian Bases of the English Art of Navigation in the Sixteenth Century". Revista da Universidade de Coimbra XXIV: 1–19 (separata). http://portalbarcosdobrasil.com.br/bitstream/handle/01/689/003164.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Woodward, David A. (1978). "English Cartography: A Summary". in Thrower, Norman J.W.. The Compleat Plattmaker. Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03522-4.

|

KSF

KSF