Banshee

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

A banshee (/ˈbænʃiː/ BAN-shee; Modern Irish bean sí, from Template:Lang-sga Template:IPA-sga, "woman of the fairy mound" or "fairy woman") is a female spirit in Irish folklore who heralds the death of a family member,[1] usually by screaming, wailing, shrieking, or keening. Her name is connected to the mythologically important tumuli or "mounds" that dot the Irish countryside, which are known as síde (singular síd) in Old Irish.[2]

Description

Sometimes she has long streaming hair, which she may be seen combing, with some legends specifying she can only keen while combing her hair. She wears a grey cloak over a green dress, and her eyes are red from continual weeping.[3] She may be dressed in white with red hair and a ghastly complexion, according to a firsthand account by Ann, Lady Fanshawe in her Memoirs.[4] Lady Wilde in her books provides others:

The size of the banshee is another physical feature that differs between regional accounts. Though some accounts of her standing unnaturally tall are recorded, the majority of tales that describe her height state the banshee's stature as short, anywhere between one foot and four feet. Her exceptional shortness often goes alongside the description of her as an old woman, though it may also be intended to emphasize her state as a fairy creature.[5]

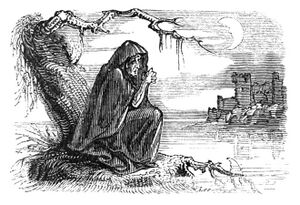

Sometimes the banshee assumes the form of some sweet-singing virgin of the family who died young, and has been given the mission by the invisible powers to become the harbinger of coming doom to her mortal kindred. Or she may be seen at night as a shrouded woman, crouched beneath the trees, lamenting with a veiled face; or flying past in the moonlight, crying bitterly: and the cry of this spirit is mournful beyond all other sounds on earth, and betokens certain death to some member of the family whenever it is heard in the silence of the night.[6]

In John O'Brien's Irish-English dictionary, the entry for Síth-Bhróg states:

"hence bean-síghe, plural mná-síghe, she-fairies or women-fairies, credulously supposed by the common people to be so affected to certain families that they are heard to sing mournful lamentations about their houses by night, whenever any of the family labours under a sickness which is to end by death, but no families which are not of an ancient & noble Stock, are believed to be honoured with this fairy privilege".[7]

Keening

In Ireland and parts of Scotland, a traditional part of mourning is the keening woman (bean chaointe), who wails a lament —in Irish: caoineadh ('weeping'), pronounced [ˈkɯiːnʲə] in the Irish dialects of Munster and southern Galway, [ˈkɯiːnʲuː] in Connacht (except south Galway) and (particularly west) Ulster, and [ˈkɯːnʲuw] in Ulster, particularly in the traditional dialects of north and east Ulster, including Louth. This keening woman may in some cases be a professional, and the best keeners would be in high demand.

Irish legend speaks of a lament being sung by a fairy woman, or banshee. She would sing it when a family member died or was about to die, even if the person had died far away and news of their death had not yet come. In those cases, her wailing would be the first warning the household had of the death.[8][9] The banshee is also a predictor of death. If someone is about to enter a situation where it is unlikely they will come out alive she will warn people by screaming or wailing, giving rise to a banshee also being known as a wailing woman. The banshee was also associated with the death coach, being said to either summon it with her keening or to travel in tandem with it.[10]

When several banshees appear at once, it indicates the death of someone great or holy.[11] The tales sometimes recounted that the woman, though called a fairy, was a ghost, often of a specific murdered woman, or a mother who died in childbirth.[3]

In some parts of Leinster, she is referred to as the bean chaointe (keening woman) whose wail can be so piercing that it shatters glass. In Scottish folklore, a similar creature is known as the bean nighe or ban nigheachain (little washerwoman) or nigheag na h-àth (little washer at the ford) and is seen washing the bloodstained clothes or armour of those who are about to die. In Welsh folklore, a similar creature is known as the cyhyraeth.[12]

Accounts reach as far back as 1380 to the publication of the Cathreim Thoirdhealbhaigh (Triumphs of Torlough) by Sean mac Craith.[13] Mentions of banshees can also be found in Norman literature of that time.[13]

Associated families

Some sources suggest that the banshee laments only the descendants of the "pure Milesian stock" of Ireland,[14][15] with the original belief appearing to associate the folklore with a number of ancient Irish families.[16][17] According to this tradition, a banshee would not lament or visit someone of Saxon or Norman descent or who came to Ireland later.[15][18][19] Most, but not all, surnames associated with banshees have the Ó or Mc/Mac prefix[20] – that is, surnames of Goidelic origin, indicating a family native to the Insular Celtic lands rather than those of the Norse, Anglo-Saxon, or Norman.

There are some exceptions to this lore,[21] including that a banshee may lament a person who had been "gifted with music and song".[22] There are accounts, for example, of the Geraldines hearing a banshee – as they had reputedly become "more Irish than the Irish themselves". And that the Bunworth Banshee, associated with the Rev. Charles Bunworth (a name of Anglo-Saxon origin), heralded the death of an Irish person who had been a patron to musicians.[citation needed]

According to tradition, some families had their own banshee,[17] with the Ua Briain banshee, named Aibell, being the ruler of 25 other banshees who would always be at her attendance.[13]

See also

- Baobhan Sith

- Cailleach

- Caoineag

- Clíodhna

- Devil Bird

- La Llorona

- Klagmuhme

- Madam Koi Koi

- Psychopomp

- Siren

- White Lady (ghost)

References

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, Celtic Folklore: Banshee.. Retrieved 11 June 2020

- ↑ Dictionary of the Irish Language: síd, síth: "a fairy hill or mound" and ben

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Briggs, Katharine (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books. pp. 14–16. ISBN 0394409183.

- ↑ Fanshawe, Herbert Charles (1907). The Memoirs of Ann, Lady Fanshawe. London: John Lane. p. 58.

- ↑ Chaplin, Kathleen (2013). "The Death Knock". New England Review, vol. 34, no. 1. pp. 135–157. JSTOR 24243011.

- ↑ Wilde, Jane (1887). Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland (Vol. 1). Boston: Ticknor and Co. pp. 259–60.

- ↑ O'Brien, John (1768). Focalóir Gaoidhilge Sax-Bhéarla. Nicolas-Francis Valleyre, Paris.

- ↑ Koch, John T. (2006-01-01). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC CLIO. pp. 189. ISBN 9781851094400. OCLC 644410117. "[Its occurrence] is most strongly associated with the old family or ancestral home and land, even when a family member dies abroad. The cry, linked predominantly to impending death, is said to be experienced by family members, and especially by the local community, rather than the dying person. Death is considered inevitable once the cry is acknowledged."

- ↑ Lysaght, Patricia; Bryant, Clifton D.; Peck, Dennis L. (15 July 2009). Encyclopedia of death and the human experience. SAGE. pp. 97. ISBN 9781412951784. OCLC 755062222. "Most manifestations of the banshee are said to occur in Ireland, usually near the home of the dying person. But some accounts refer to the announcement in Ireland of the deaths of Irish people overseas... It is those concerned with a death, at family and community levels, who usually hear the banshee, rather than the dying person."

- ↑ "death coach" (in en). doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095704757. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095704757.

- ↑ Yeats, W. B. "Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry" in Booss, Claire; Yeats, W.B.; Gregory, Lady (1986) A Treasury of Irish Myth, Legend, and Folklore. New York: Gramercy Books. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-517-48904-8

- ↑ Owen, Elias (1887). Welsh folk-lore: A collection of the folk-tales and legends of North Wales. Felinfach: Llanerch. p. 142.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Westropp, Thos. J. (June 1910). "A Folklore Survey of County Clare". Folklore 21 (2): 180–199. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1910.9719928. https://zenodo.org/record/2311341.

- ↑ Scott, Walter (1836-01-01) (in en). Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. Harper & Brothers. p. 296. https://archive.org/details/lettersondemono00unkngoog. "sir walter scott letters on demonology banshee."

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 (in en) The London Journal: and Weekly Record of Literature, Science, and Art. G. Vickers. 1847. https://books.google.com/books?id=AIU-AQAAMAAJ&dq=%22banshee%22+%22kavanagh%22&pg=RA1-PA109. "the Banshee is only allowed to families of pure Milesian stock, and is never ascribed to any descendant of the [..] Saxon who followed the banner of Earl Strongbow"

- ↑ Monaghan, Patricia (2009-12-18) (in en). Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines [2 volumes: [2 volumes]]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-34990-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=uabOEAAAQBAJ&q=Encyclopedia+of+Goddesses+and+Heroines+%5B2+volumes%5D:+%5B2+volumes%5D.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Croker, Thomas Crofton (1838) (in en). Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland. [By Thomas Crofton Croker.]. John Murray; Thomas Tegg&Son. p. 260. https://books.google.com/books?id=ltoDAAAAQAAJ&q=Fairy+Legends+and+Traditions+of+the+South+of+Ireland+croker. "the Banshee, or female demon [was] attached to certain ancient Irish families"

- ↑ Scott, Walter (1831) (in en). Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft: Addressed to J. G. Lockhart, Esq. John Murray. https://books.google.com/books?id=mzNN3Zv6nQQC.

- ↑ Vallancey, Charles (1786) (in en). Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicus. T. Ewing. p. 461. https://books.google.com/books?id=7blVAAAAcAAJ. ""but no families which are not of an ancient and noble stock (no oriental extraction, he should have said) are believed to be honoured with this fairy privilege""

- ↑ Cashman, Ray (2016-08-30) (in en). Packy Jim: Folklore and Worldview on the Irish Border. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 145. ISBN 9780299308902. https://books.google.com/books?id=8LvkDAAAQBAJ&q=banshee+names+irish. "The banshee always keens for the Macs and the Os, people with the old Celtic names"

- ↑ O'Sullivan, Friar (1899). "Ancient History of the Kingdom of Kerry". Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 5 (44): 224–234. http://www.corkhist.ie/wp-content/uploads/jfiles/1899/b1899-036.pdf. "It is only "blood" can have a banshee. Business men nowadays have something as good as "blood" - they have "brains" and "brass" by which they can compete with and enter into the oldest families [..] Nothing, however [..] can replace "Blue Blood/"".

- ↑ Wilde, Lady (1887) (in en). Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland. Ticknor and Company. p. 259. https://books.google.com/books?id=eUH1_l0w5a0C&q=never+ascribe+to+a+descendant+bean+sidhe. "only certain families of historic lineage, or persons gifted with music and song, are attended by this spirit [banshee]"

Further reading

- Sorlin, Evelyne (1991) (in fr). Cris de vie, cris de mort: Les fées du destin dans les pays celtiques. Academia Scientiarum Fennica. ISBN 978-951-41-0650-7.

- Lysaght, Patricia (1986). The banshee: The Irish death-messenger. Roberts Rinehart. ISBN 978-1-57098-138-8. https://archive.org/details/bansheeirishdeat0000lysa.

- Evans-Wentz, Walter Yeeling (1977). The Fairy-Faith in celtic countries, its psychological origin and nature. C. Smythe. OCLC 257400792.

External links

|

KSF

KSF