Empowerment (Vajrayana)

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

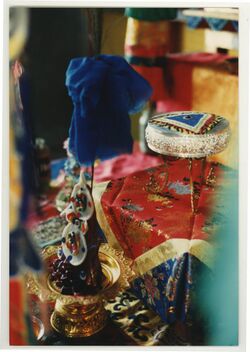

An empowerment is a ritual in Vajrayana which initiates a student into a particular tantric deity practice. The Tibetan word for this is wang (Skt. abhiṣeka; Tib. དབང་, wang; Wyl. dbang),[1] which literally translates to power. The Sanskrit term for this is abhiseka which literally translates to sprinkling or bathing or anointing.[2] A tantric practice is not considered effective or as effective until a qualified master has transmitted the corresponding power of the practice directly to the student. This may also refer to introducing the student to the mandala of the deity.

There are three requirements before a student may begin a practice:[3][4][5][6]

- the empowerment (Tibetan: wang)

- a reading of the text by an authorized holder of the practice (Tibetan: lung)

- instruction on how to perform the practice or rituals (Tibetan: tri).

An individual is not allowed to engage in a deity practice without the empowerment for that practice. The details of an empowerment ritual are often kept secret as are the specific rituals involved in the deity practice.[7]

Commitment

By receiving the empowerment, the student enters into a samaya connection with the teacher. At the level of the anuttarayoga tantra class of practices; the samayas traditionally entail fourteen points of observance. The vajra master may also include particular directives, such as specifying that the student complete a certain amount of practice.

Process

The ritual for performing an empowerment can be divided into four parts:

- 'vase' (Tibetan: bumpa) or water empowerment

- secret (Sanskrit: guhya) empowerment

- knowledge-wisdom (Sanskrit: prajna-jnana) empowerment

- word, fourth, or suchness empowerment[8]

The ritual is based on the coronation process of a king but in this case represents the student being empowered as the deity of the practice (i.e. a Buddha).[9] The vase empowerment symbolizes purification of the body, senses, and world into the body of the deity and may include a vase filled with water or washing. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche compared that to baptism.[citation needed] The secret empowerment involves receiving nectar to purify the breath and speech into the speech of that deity. The knowledge-wisdom empowerment involves uniting with a real or imaginary consort, called the prajna, to experience the blissful wisdom (jnana) mind of the deity. The word empowerment involves means by word, sound, or symbols to realize the union, mind essence or mind nature, or the suchness of the deity.[2][10][11][12][13]

Pointing-out instructions

In the Kagyu and Nyingma traditions of Mahāmudrā and Dzogchen, respectively, one finds "pointing-out instruction" conferred outside of the context of formal abhiṣeka. Whether or not such instructions are valid without the formal abhiṣeka has historically been a point of contention with the more conservative Gelug and Sakya lineages. The pointing-out instruction is often equated with the "fourth" or word abhiṣeka.

See also

- Abhiseka

- Adhisthana

- Dharma transmission

- Esoteric transmission

- Lineage (Buddhism)

- Lung (Tibetan Buddhism)

- Sadhana

Notes

- ↑ "Empowerment". Rigpa Wiki. http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Empowerment. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Trungpa (1985) pp.92-93

- ↑ "Glossary". United Trungram Buddhist Fellowship. http://www.utbf.org/en/resources/glossary/. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ "Interview with Trinley Thaye Dorje, the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa". Buddhism Today, Vol.8. Diamond Way Buddhism, USA. 2000. Archived from the original on February 13, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20050213192000/http://diamondway.org/usa/3kar17_intrv.php. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ "Vajrayana". Kagyu Samye Ling Monastery and Tibetan Centre. http://www.samyeling.org/index.php?module=Pagesetter&func=viewpub&tid=30&pid=10. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ Mingyur Dorje Rinpoche. "Vajrayana and Empowerment". Kagyu Samye Ling Monastery and Tibetan Centre. http://www.samyeling.org/index.php?module=Pagesetter&func=viewpub&tid=11&pid=47. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ "The Meaning of Empowerment". The Bodhicitta Foundation. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25. https://web.archive.org/web/20071225104041/http://buddhism.inbaltimore.org/empowerment.html. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ "Empowerment". Khandro.Net. http://www.khandro.net/TibBud_empowerment.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ Dhavamony (1973) p.187

- ↑ Beer (2004) p.219

- ↑ Trungpa (1991) p. 153-156

- ↑ Rangdrol (1997) 17-18, 25, 39

- ↑ Kongtrul (2005)225, 229, 231-233

- Dhavamony, Mariasusai (1973) Phenomenology of Religion ISBN 88-7652-474-6 p. 187

- Beer, Robert (2004) The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs ISBN 1-932476-10-5

- Trungpa, Chögyam (1985) Journey without Goal ISBN 0-394-74194-3

- Trungpa, Chogyam (1991) The Heart of the Buddha ISBN 0-87773-592-1

- Rangdrol, Tsele Natsok (1993) Empowerment and the Path of Liberation ISBN 962-7341-15-0

- Kongtrul Lodro Thaye, Jamgon (2005) The Treasury of Knowledge, Book Six, Part Four, Systems of Buddhist Tantra ISBN 1-55939-210-X

KSF

KSF