Faust

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

Faust is the protagonist of a classic German legend, based on the historical Johann Georg Faust (c. 1480–1540).

The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroads, exchanging his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. The Faust legend has been the basis for many literary, artistic, cinematic, and musical works that have reinterpreted it through the ages. "Faust" and the adjective "Faustian" imply a situation in which an ambitious person surrenders moral integrity in order to achieve power and success for a limited term.[1][2]

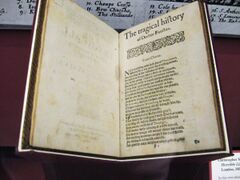

The Faust of early books — as well as the ballads, dramas, movies, and puppet-plays which grew out of them — is irrevocably damned because he prefers human to divine knowledge: "he laid the Holy Scriptures behind the door and under the bench, refused to be called doctor of theology, but preferred to be styled doctor of medicine".[1] Plays and comic puppet theatre loosely based on this legend were popular throughout Germany in the 16th century, often reducing Faust and Mephistopheles to figures of vulgar fun. The story was popularised in England by Christopher Marlowe, who gave it a classic treatment in his play, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (whose date of publication is debated, but likely around 1587).[3] In Goethe's reworking of the story two hundred years later, Faust becomes a dissatisfied intellectual who yearns for "more than earthly meat and drink" in his life.

Summary of the story

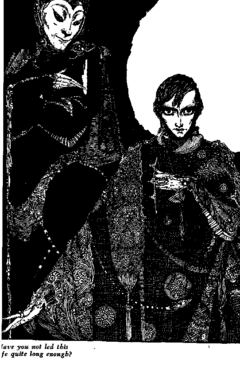

Faust is bored and depressed with his life as a scholar. After an attempt to take his own life, he calls on the Devil for further knowledge and magic powers with which to indulge all the pleasure and knowledge of the world. In response, the Devil's representative, Mephistopheles, appears. He makes a bargain with Faust: Mephistopheles will serve Faust with his magic powers for a set number of years, but at the end of the term, the Devil will claim Faust's soul, and Faust will be eternally enslaved.

During the term of the bargain, Faust makes use of Mephistopheles in various ways. In Goethe's drama, and many subsequent versions of the story, Mephistopheles helps Faust seduce a beautiful and innocent girl, usually named Gretchen, whose life is ultimately destroyed when she gives birth to Faust's bastard son. Realizing this unholy act she drowns the child and is held for murder. However, Gretchen's innocence saves her in the end, and she enters Heaven after execution. In Goethe's rendition, Faust is saved by God via his constant striving — in combination with Gretchen's pleadings with God in the form of the eternal feminine. However, in the early tales, Faust is irrevocably corrupted and believes his sins cannot be forgiven; when the term ends, the Devil carries him off to Hell.

Sources

Many aspects of the life of Simon Magus are echoed in the Faust legend of Christopher Marlowe and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Hans Jonas writes, "surely few admirers of Marlowe's and Goethe's plays have an inkling that their hero is the descendant of a gnostic sectary and that the beautiful Helen called up by his art was once the fallen Thought of God through whose raising mankind was to be saved."[4] The tale of Faust bears many similarities to the Theophilus legend recorded in the 13th century, writer Gautier de Coincy's Les Miracles de la Sainte Vierge. Here, a saintly figure makes a bargain with the keeper of the infernal world but is rescued from paying his debt to society through the mercy of the Blessed Virgin.[5] A depiction of the scene in which he subordinates himself to the Devil appears on the north tympanum of the Cathedrale de Notre Dame de Paris.[6]

The origin of Faust's name and persona remains unclear.[dubious ] The character is ostensibly based on Johann Georg Faust (c. 1480–1540), a magician and alchemist probably from Knittlingen, Württemberg, who obtained a degree in divinity from Heidelberg University in 1509, but the legendary Faust has also been connected with Johann Fust (c. 1400–1466), Johann Gutenberg's business partner,[7] which suggests that Fust is one of the multiple origins to the Faust story.[8] Scholars such as Frank Baron[9] and Leo Ruickbie[10] contest many of these[which?] previous assumptions.[clarification needed]

The character in Polish folklore named Pan Twardowski presents similarities with Faust. The Polish story seems to have originated at roughly the same time as its German counterpart, yet it is unclear whether the two tales have a common origin or influenced each other. The historical Johann Georg Faust had studied in Kraków for a time, and may have served as the inspiration for the character in the Polish legend.

The first known printed source of the legend of Faust is a small chapbook bearing the title Historia von D. Johann Fausten, published in 1587. The book was re-edited and borrowed from throughout the 16th century. Other similar books of that period include:

- Das Wagnerbuch (1593)

- Das Widmann'sche Faustbuch (1599)

- Dr. Fausts großer und gewaltiger Höllenzwang (Frankfurt 1609)

- Dr. Johannes Faust, Magia naturalis et innaturalis (Passau 1612)

- Das Pfitzer'sche Faustbuch (1674)

- Dr. Fausts großer und gewaltiger Meergeist (Amsterdam 1692)

- Das Wagnerbuch (1714)

- Faustbuch des Christlich Meynenden (1725)

The 1725 Faust chapbook was widely circulated and also read by the young Goethe.

Related tales about a pact between man and the Devil include the plays Mariken van Nieumeghen (Dutch, early 16th century, author unknown), Cenodoxus (German, early 17th century, by Jacob Bidermann) and The Countess Cathleen (Irish Legend of unknown origin believed by some to be taken from the French play Les marchands d'âmes).

Locations linked to the story

Staufen, a town in the extreme southwest of Germany, claims to be where Faust died (c. 1540); depictions appear on buildings, etc. The only historical source for this tradition is a passage in the Chronik der Grafen von Zimmern, which was written around 1565, 25 years after Faust's presumed death. These chronicles are generally considered reliable, and in the 16th century there were still family ties between the lords of Staufen and the counts of Zimmern in nearby Donaueschingen.[11]

In Christopher Marlowe's original telling of the tale, Wittenburg where Faust studied was also written as Wertenberge. This has led to a measure of speculation as to where precisely his story is set. Some scholars have suggested the Duchy of Württemberg; others have suggested an allusion to Marlowe's own Cambridge (Gill, 2008, p. 5)

Literary interpretations

Marlowe's Doctor Faustus

The early Faust chapbook, while in circulation in northern Germany, found its way to England, where in 1592 an English translation was published, The Historie of the Damnable Life, and Deserved Death of Doctor Iohn Faustus credited to a certain "P. F., Gent[leman]". Christopher Marlowe used this work as the basis for his more ambitious play, The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (published c. 1604). Marlowe also borrowed from John Foxe's Book of Martyrs, on the exchanges between Pope Adrian VI and a rival pope.

Goethe's Faust

Another important version of the legend is the play Faust, written by the German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. The first part, which is the one more closely connected to the earlier legend, was published in 1808, the second posthumously in 1832.

Goethe's Faust complicates the simple Christian moral of the original legend. A hybrid between a play and an extended poem, Goethe's two-part "closet drama" is epic in scope. It gathers together references from Christian, medieval, Roman, eastern, and Hellenic poetry, philosophy, and literature.

The composition and refinement of Goethe's own version of the legend occupied him for over sixty years (though not continuously). The final version, published after his death, is recognized as a great work of German literature.

The story concerns the fate of Faust in his quest for the true essence of life ("was die Welt im Innersten zusammenhält"). Frustrated with learning and the limits to his knowledge, power, and enjoyment of life, he attracts the attention of the Devil (represented by Mephistopheles), who makes a bet with Faust that he will be able to satisfy him; a notion that Faust is incredibly reluctant towards, as he believes this happy zenith will never come. This is a significant difference between Goethe's "Faust" and Marlowe's; Faust is not the one who suggests the wager.

In the first part, Mephistopheles leads Faust through experiences that culminate in a lustful relationship with Gretchen, an innocent young woman. Gretchen and her family are destroyed by Mephistopheles' deceptions and Faust's desires. Part one of the story ends in tragedy for Faust, as Gretchen is saved but Faust is left to grieve in shame.

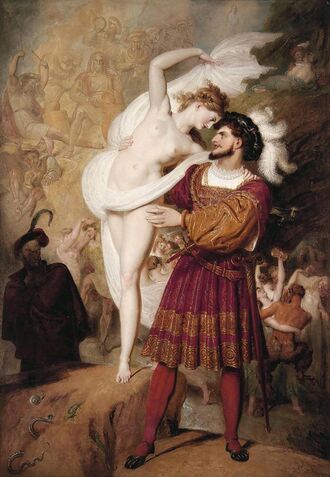

The second part begins with the spirits of the earth forgiving Faust (and the rest of mankind) and progresses into allegorical poetry. Faust and his Devil pass through and manipulate the world of politics and the world of the classical gods, and meet with Helen of Troy (the personification of beauty). Finally, having succeeded in taming the very forces of war and nature, Faust experiences a singular moment of happiness.

Mephistopheles tries to seize Faust's soul when he dies after this moment of happiness, but is frustrated and enraged when angels intervene due to God's grace. Though this grace is truly 'gratuitous' and does not condone Faust's frequent errors perpetrated with Mephistopheles, the angels state that this grace can only occur because of Faust's unending striving and due to the intercession of the forgiving Gretchen. The final scene has Faust's soul carried to heaven in the presence of God by the intercession of the "Virgin, Mother, Queen, ... Goddess kind forever... Eternal Womanhood.[12] The Goddess is thus victorious over Mephistopheles, who had insisted at Faust's death that he would be consigned to "The Eternal Empty."

Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita

Søren Kierkegaard, Either/Or, Immediate Stages of the Erotic

The story of Faust is woven into Dr. Mikhail Bulgakov's best-known novel, The Master and Margarita (1928–1940) with Margarita being modeled on Gretchen and the Master on Faust.[citation needed] Other characters in the novel include Woland (whose description recalls Mephistopheles) and Mikhail Alexandrovitch Berlioz (the head of Massolit).

Mann's Doctor Faustus

Thomas Mann's 1947 Doktor Faustus: Das Leben des deutschen Tonsetzers Adrian Leverkühn, erzählt von einem Freunde adapts the Faust legend to a 20th-century context, documenting the life of fictional composer Adrian Leverkühn as analog and embodiment of the early 20th-century history of Germany and of Europe. The talented Leverkühn, after contracting venereal disease from a brothel visit, forms a pact with a Mephistophelean character to grant him 24 years of brilliance and success as a composer. He produces works of increasing beauty to universal acclaim, even while physical illness begins to corrupt his body. In 1930, when presenting his final masterwork (The Lamentation of Dr Faust ), he confesses the pact he had made: madness and syphilis now overcome him, and he suffers a slow and total collapse until his death in 1940. Leverkühn's spiritual, mental, and physical collapse and degradation are mapped on to the period in which Nazism rose in Germany, and Leverkühn's fate is shown as that of the soul of Germany.

Benét's The Devil and Daniel Webster

Stephen Vincent Benét's short story The Devil and Daniel Webster published in 1937 is a retelling of the tale of Faust based on the short story The Devil and Tom Walker, written by Washington Irving. Benet's version of the story centers on a New Hampshire farmer by the name of Jabez Stone who, plagued with unending bad luck, is approached by the devil under the name of Mr. Scratch who offers him seven years of prosperity in exchange for his soul. Jabez Stone is eventually defended by Daniel Webster, a fictional version of the famous lawyer and orator, in front of a judge and jury of the damned, and his case is won. It was adapted in 1941 as The Devil and Daniel Webster with James Craig as Jabez and Edward Arnold as Webster. It was remade in 2007 as Shortcut to Happiness with Alec Baldwin as Jabez and Anthony Hopkins as Webster.

Selected additional dramatic works

- Faust (1836) by Nikolaus Lenau[13]

- Faust (1839) Ludwig Hermann Wolfram

- Doctor Faust. Dance Poem (1851) by Heinrich Heine

- Faust: The Third Part of the Tragedy (1862) by Friedrich Theodor Vischer

- The Death of Doctor Faustus (1925) by Michel de Ghelderode

- Mephisto (1933) Klaus Mann

- Faust, a Subjective Tragedy (1934) by Fernando Pessoa

- Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights (1938) by Gertrude Stein

- My Faust (1940) by Paul Valéry

- Doctor Faustus (1979) by Don Nigro

- Temptation (1985) by Václav Havel (Translated by Marie Winn)

- Faustus (2004) by David Mamet

- Wittenberg (2008) by David Davalos

- Faust (2009) by Edgar Brau

- Faust 3 (2016) by Peter Schumann, Bread and Puppet Theater

Selected additional novels, stories, poems, and comics

- The Devil and Tom Walker (1824) by Washington Irving

- Faust (1855) novella by Ivan Turgenev

- The Cobbler and the Devil (1863) by August Šenoa

- Fausto (1866) by Estanislao del Campo

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) by Oscar Wilde

- Faust (1980) by Robert Nye

- Mefisto (1986) by John Banville

- Eric (1990) by Terry Pratchett

- Jack Faust (1997) by Michael Swanwick

- Frau Faust (2014–Present) by Kore Yamazaki

- Soul Cartel (2014–2017) by Haram and Youngji Kim

- Teeth in the Mist (2019) by Dawn Kurtagich

Cinematic interpretations

Early films

- Faust, an obscure (now lost) 1921 American silent film directed by Frederick A. Todd[14]

- Faust, a 14-minute-long 1922 British silent film directed by Challis Sanderson[15]

- Faust, a 1922 French silent film directed by Gerard Bourgeois, regarded as the first ever 3-D film[15]

Murnau's Faust

F.W. Murnau, director of the classic Nosferatu, directed a silent version of Faust that premiered in 1926. Murnau's film featured special effects that were remarkable for the era. Many of these shots are impressive today.[16]

In one, Mephisto towers over a town, dark wings spread wide, as a fog rolls in bringing the plague. In another, an extended montage sequence shows Faust, mounted behind Mephisto, riding through the heavens, and the camera view, effectively swooping through quickly changing panoramic backgrounds, courses past snowy mountains, high promontories and cliffs, and waterfalls.

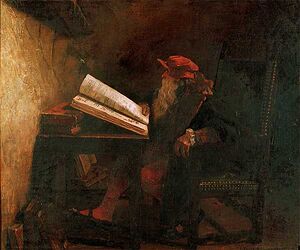

In the Murnau version of the tale, the aging bearded scholar and alchemist, now disillusioned—by a palpable failure of his antidotal, dark liquid in a phial, a supposed cure for victims in his plague-stricken town—Faust renounces his many years of hard travail and studies in alchemy. We see this despair, watching him haul all his bound volumes by armloads onto a growing pyre; he intends to burn everything. But a wind comes, from offscreen, that turns over a few cabalistic leaves—from one of the books' pages, sheets not yet in flames, one and another just catching Faust's eye. Their words contain a prescription for how to invoke the dreadful dark forces.

Following Faust heeding these recipes, we see him begin enacting the mystic protocols: on a hill, alone, summoning Mephisto, certain forces begin to convene, and Faust in a state of growing trepidation hesitates, and begins to withdraw; he flees along a winding, twisting pathway, returning to his study chambers. At pauses along this retreat, though, he meets a reappearing figure. Each time, it doffs its hat—in a greeting, that is Mephisto, confronting him. Mephisto overcomes Faust's reluctance to sign a long binding pact with the invitation that Faust may try on these powers, just for one day, and without obligation to longer terms. It comes the end of that day, the sands of twenty-four hours having run out, after Faust's having been restored to youth and, helped by his servant Mephisto to steal a beautiful woman from her wedding feast, Faust is tempted so much that he agrees to sign a pact for eternity (which is to say when, in due course, his time runs out). Eventually Faust becomes bored with the pursuit of pleasure and returns home, where he falls in love with the beautiful and innocent Gretchen. His corruption (enabled, or embodied, through the forms of Mephisto) ultimately ruins both their lives, though there is still a chance for redemption in the end.

Similarities to Goethe's Faust include the classic tale of a man who sold his soul to the Devil, the same Mephisto wagering with an angel to corrupt the soul of Faust, the plague sent by Mephisto on Faust's small town, and the familiar cliffhanger with Faust unable to find a cure for The Plague, and therefore turning to Mephisto, renouncing God, the angel, and science alike.

La Beauté du diable (The Beauty of the Devil)

Directed by René Clair, 1950 – A somewhat comedic adaptation with Michel Simon as Mephistopheles/Faust as old man, and Gérard Philipe as Faust transformed into a young man.

Phantom of the Paradise

Directed by Brian DePalma, 1974 - A vain rock impresario, who has sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for eternal youth, corrupts and destroys a brilliant but unsuccessful songwriter and a beautiful ingenue.

Mephisto

Directed by István Szabó, 1981 – An actor in 1930s Germany aligns himself with the Nazi party for prestige.

Lekce Faust (Faust)

Directed by Jan Švankmajer, 1994 – The source material of Švankmajer's film is the Faust legend; including traditional Czech puppet show versions, this film production uses a variety of cinematic formats, such as stop-motion photography animation and claymation.

Faust

Directed by Aleksandr Sokurov, 2011 – German-language film starring Johannes Zeiler, Anton Adasinsky, Isolda Dychauk.

American Satan

Directed by Ash Avildsen, 2017 – A rock and roll modern retelling of the Faust legend starring Andy Biersack as Johnny Faust.[17]

Directed by Philipp Humm, 2019 – a contemporary feature art film directly based on Goethe's Faust, Part One and Faust, Part Two.[18] The film is the first filmed version of Faust, I and Faust, II as well as a part of Humm's Gesamtkunstwerk, an art project with over 150 different artworks such as paintings, photos, sculptures, drawings and an illustrated novella. [19][20]

Television interpretations

Chespirito's Faust

Mexican comedian Chespirito acted as Faust in a sketch adaptation of the legend. Ramon Valdez played Mephistopheles (presenting himself also as The Devil), and in this particular version, Faust sells his soul by signing a contract, after which Mephistopheles gives him an object known as the "Chirrín-Chirrión" (which resembles a horse whip) which grants him the power to make things, people or even youth or age, appear or disappear, by speaking the object's name, followed by the word "Chirrín" (for them to appear) or "Chirrión" (for them to disappear). After Faust's youth is restored, he uses his powers to try conquering the heart of his assistant Margarita (played by Florinda Meza). However, after several failed (and funny) attempts to do so, he discovers she already has a boyfriend, and realizes he sold his soul for nothing. At this point, Mephistopheles returns to take Faust's soul to hell, producing the signed contract for supporting his claim. Faust responds by using the Chirrín-Chirrión to make the contract itself disappear, which makes Mephistopheles cry.

Musical interpretations

Operatic

The Faust legend has been the basis for several major operas: for a more complete list, visit Works based on Faust

- Mefistofele, the only completed opera by Arrigo Boito

- Doktor Faust, begun by Ferruccio Busoni and completed by his pupil Philipp Jarnach

- Faust, by Charles Gounod to a French libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré from Carré's play Faust et Marguerite, in turn loosely based on Goethe's Faust, Part 1

- Faust (Spohr), one of the earliest operatic adaptations of the story, with separate versions premiering in 1816 and 1852 respectively.

- Hector Berlioz's La Damnation de Faust (1846)

Symphonic

Faust has inspired major musical works in other forms:

- Faust Overture by Richard Wagner

- Scenes from Goethe's Faust by Robert Schumann

- Faust Symphony by Franz Liszt

- Symphony No. 8 by Gustav Mahler

- Histoire du soldat by Igor Stravinsky

- Faust was the title and inspiration of Phantom Regiment Drum and Bugle Corps' 2006 show.

Other adaptions

- Faustian Echoes by American black metal band Agalloch

- Faust Arp by English rock band Radiohead. From the album In Rainbows.

- The Small Print by English rock band Muse. From the album Absolution. Originally titled Action Faust, it is an interpretation of the tale from the Devil's perspective.

- Bohemian Rhapsody by English rock band Queen. From the album A Night at the Opera.

- Faust by English virtual band Gorillaz. From the album G-Sides.

- Absinthe with Faust by English extreme metal band Cradle of Filth. From the album Nymphetamine.

- Urfaust, The Calling, The Oath, Conjuring the Cull, and The Harrowing by American death metal band Misery Index. The first five tracks from the album The Killing Gods. A five-song, modern interpretation of Goethe's Faust.

- Epica and The Black Halo by international power metal band Kamelot. A two-album interpretation of the tale.

- Faust by American metalcore band The Human Abstract. From the album Digital Veil.

- Faust by horrorcore rapper SickTanicK feat. Texas Microphone Massacre. From the album Chapter 3: Awake (The Ministry of Hate).

- Faust, Midas and Myself by American alternative rock band Switchfoot. From the album Oh! Gravity.

- The Faustian Alchemist by Finnish black metal band Belzebubs. From the album Pantheon of the Nightside Gods.

- Randy Newman’s Faust. A rock opera written and co-produced by Randy Newman with: Don Henley as Faust; Randy Newman as the devil; James Taylor as the Lord; Bonnie Raitt as Martha; and Linda Ronstadt as Margaret.

- Damn Yankees was a 1950s musical inspired by the legend.

In psychotherapy

Psychodynamic therapy uses the idea of a Faustian bargain to explain defence mechanisms, usually rooted in childhood, that sacrifice elements of the self in favor of some form of psychical survival. For the neurotic, abandoning one's genuine feeling self in favour of a false self more amenable to caretakers may offer a viable form of life, but at the expense of one's true emotions and affects.[21] For the psychotic, a Faustian bargain with an omnipotent self can offer the imaginary refuge of a psychic retreat, at the price of living in unreality.[22]

See also

- Deal with the Devil

- Pan Twardowski

- Jonathan Moulton, the "Yankee Faust"

- Works based on Faust

- Robert Johnson

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). "Faust". in Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "Faustian" – pertaining to or resembling or befitting Faust or Faustus especially in insatiably striving for worldly knowledge and power even at the price of spiritual values; "a Faustian pact with the Devil". http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Faustian

- ↑ "Christopher Marlowe". http://www.biography.com/people/christopher-marlowe-9399572.

- ↑ Jonas, Hans (1958). The Gnostic Religion. p. 111.

- ↑ An 1875 edition is at: Coincy, Par Gautier de; Par M L'Abbé Poquet (1857) (in fr). Les miracles de la Sainte Vierge. Parmantier/Didron. https://books.google.com/books?id=nwedgt6DDtoC&pg=PR3.

- ↑ See, for example, this photo at: Ballegeer, Stephen. "Notre-Dame, Paris: Portal on the north transept". https://www.flickr.com/photos/uncle_buddha/220748038/.

- ↑ Meggs, Philip B.; Purvis, Alston W. (2006). Meggs' History of Graphic Design, Fourth Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. p. 73. ISBN 0-471-69902-0.

- ↑ Jensen, Eric (Autumn 1982). "Liszt, Nerval, and "Faust"". 19th-Century Music (University of California Press) 6 (2): 153. doi:10.2307/746273.

- ↑ Baron, Frank (1978). Doctor Faustus, from History to Legend. Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

- ↑ Ruickbie, Leo (2009). Faustus: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5090-9.

- ↑ Geiges, Leif (1981). Faust's Tod in Staufen: Sage – Dokumente. Freiburg im Breisgau: Kehrer Verlag KG.

- ↑ Goethe, Faust, Part Two, lines 12101–12110, translation: David Luke, Oxford World Classics, ISBN 9780199536207.

- ↑ Pagel, Louis. Doctor Faustus of the popular legend Marlowe, the Puppet-Play, Goethe, and Lenau, treated historically and critically.. pp. 46.

- ↑ Workman, Christopher; Howarth, Troy (2016). Tome of Terror: Horror Films of the Silent Era. Midnight Marquee Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-1936168-68-2.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Workman, Christopher; Howarth, Troy (2016). "Tome of Terror: Horror Films of the Silent Era". Midnight Marquee Press. p. 249.ISBN 978-1936168-68-2.

- ↑ "F.W. Murnau | German director" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/biography/F-W-Murnau.

- ↑ "American Satan (2017)". https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5451690/plotsummary.

- ↑ "The Last Faust" (in en). https://www.imdb.com/title/tt8871254/.

- ↑ Feay, Suzi (2019-11-29). "The Last Faust: Steven Berkoff stars in Philipp Humm’s take on Goethe". https://www.ft.com/content/4a9403cc-110e-11ea-a7e6-62bf4f9e548a.

- ↑ Humm, Philipp. "The Last Faust - Ein Gesamtkunstwerk". https://philipphumm.art/the-last-faust/.

- ↑ D. Fosha, The Transforming Power of Affect (2000) p. 83

- ↑ P. Williams, A Language of Psychosis (2001) p. 23

Sources

- Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, edited and with an introduction by Sylvan Barnet. Signet Classics, 1969.

- J. Scheible, Das Kloster (1840s).

Further reading

- The Faustian Century: German Literature and Culture in the Age of Luther and Faustus. Ed. J. M. van der Laan and Andrew Weeks. Camden House, 2013. ISBN 978-1571135520

- A philosophical interpretation: Seung, T.K.. Cultural Thematics: The Formation of the Faustian Ethos. Yale University Press. 1976. ISBN 978-0300019186

External links

- Faust, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Juliette Wood, Osman Durrani & Rosemary Ashton (In Our Time, Dec. 23, 2004)

KSF

KSF