Geryon

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 11 min

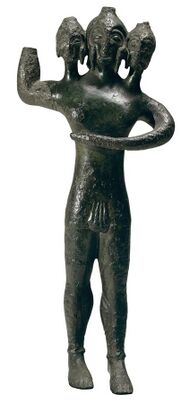

In Greek mythology, Geryon (/ˈdʒɪəriən/ or /ˈɡɛriən/;[Note 1] also Geryone; Greek: Γηρυών,[Note 2] genitive: Γηρυόνος), son of Chrysaor and Callirrhoe, the grandson of Medusa and the nephew of Pegasus, was a fearsome giant who dwelt on the island Erytheia of the mythic Hesperides in the far west of the Mediterranean. A more literal-minded later generation of Greeks associated the region with Tartessos in southern Iberia.[Note 3] Geryon was often described as a monster with either three bodies and three heads, or three heads and one body, or three bodies and one head. He is commonly accepted as being mostly humanoid, with some distinguishing features (such as wings, or multiple bodies etc.) and in mythology, famed for his cattle.

Appearance

According to Hesiod[Note 4] Geryon had one body and three heads, whereas the tradition followed by Aeschylus gave him three bodies.[Note 5] A lost description by Stesichoros said that he has six hands and six feet and is winged;[1] there are some mid-6th century BC Chalcidian vases portraying Geryon as winged. Some accounts state that he had six legs as well while others state that the three bodies were joined to one pair of legs. Apart from these bizarre features, his appearance was that of a warrior. He owned a two-headed hound named Orthrus, which was the brother of Cerberus, and a herd of magnificent red cattle that were guarded by Orthrus, and a herder Eurytion, son of Erytheia.[Note 6]

Mythology

The Tenth Labour of Heracles

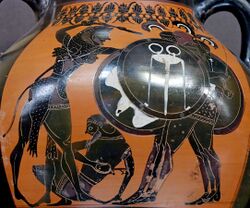

In the fullest account in the Bibliotheke of Pseudo-Apollodorus,[2] Heracles was required to travel to Erytheia, in order to obtain the Cattle of Geryon (Γηρυόνου βόες) as his tenth labour. On the way there, he crossed the Libyan desert[Note 7] and became so frustrated at the heat that he shot an arrow at Helios, the Sun. Helios "in admiration of his courage" gave Heracles the golden cup he used to sail across the sea from west to east each night. Heracles used it to reach Erytheia, a favorite motif of the vase-painters. Such a magical conveyance undercuts any literal geography for Erytheia, the "red island" of the sunset.

When Heracles reached Erytheia, no sooner had he landed than he was confronted by the two-headed dog, Orthrus. With one huge blow from his olive-wood club, Heracles killed the watchdog. Eurytion, the herdsman, came to assist Orthrus, but Heracles dealt with him the same way.

On hearing the commotion, Geryon sprang into action, carrying three shields, three spears, and wearing three helmets. He pursued Heracles at the River Anthemus but fell victim to an arrow that had been dipped in the venomous blood of the Lernaean Hydra, shot so forcefully by Heracles that it pierced Geryon's forehead, "and Geryon bent his neck over to one side, like a poppy that spoils its delicate shapes, shedding its petals all at once".[Note 8]

Heracles then had to herd the cattle back to Eurystheus. In Roman versions of the narrative, on the Aventine Hill in Italy, Cacus stole some of the cattle as Heracles slept, making the cattle walk backwards so that they left no trail, a repetition of the trick of the young Hermes. According to some versions, Heracles drove his remaining cattle past a cave, where Cacus had hidden the stolen animals, and they began calling out to each other. In others, Caca, Cacus' sister, told Heracles where he was. Heracles then killed Cacus, and according to the Romans, founded an altar where the Forum Boarium, the cattle market, was later held.

To annoy Heracles, Hera sent a gadfly to bite the cattle, irritate them and scatter them. The hero was within a year able to retrieve them. Hera then sent a flood which raised the level of a river so much, Heracles could not cross with the cattle. He piled stones into the river to make the water shallower. When he finally reached the court of Eurystheus, the cattle were sacrificed to Hera.

In the Aeneid, Vergil may have based the triple-souled figure of Erulus, king of Praeneste, on Geryon[3] and Hercules' conquest of Geryon is mentioned in Book VIII. The Herculean Sarcophagus of Genzano features a three-headed representation of Geryon.[4]

Stesichorus' account

The poet Stesichorus wrote a poem "Geryoneis" (Γηρυονηΐς) in the sixth century BC, which was apparently the source of this section in Bibliotheke; it contains the first reference to Tartessus. From the fragmentary papyri found at Oxyrhyncus[5] it is possible (although there is no evidence) that Stesichorus inserted a character, Menoites, who reported the theft of the cattle to Geryon. Geryon then had an interview with his mother Callirrhoe, who begged him not to confront Heracles. They appear to have expressed some doubt as to whether Geryon would prove to be immortal. The gods met in council, where Athena warned Poseidon that she would protect Heracles against Poseidon's grandson Geryon. Denys Page observes that the increase in representation of the Geryon episode in vase-paintings increased from the mid-sixth century and suggests that Stesichorus' "Geryoneis" provided the impetus.

The fragments are sufficient to show that the poem was composed in twenty-six line triads, of strophe, antistrophe and epode, repeated in columns along the original scroll, facts that aided Page in placing many of the fragments, sometimes of no more than a word, in what he believed to be their proper positions.

Pausanias' account

In his work Description of Greece, Pausanias mentions that Geryon had a daughter, Erytheia, who had a son with Hermes, Norax, the founder of the city of Nora in Sardinia.[Note 9]

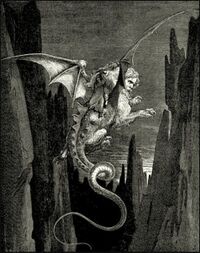

In Dante's Inferno

The Geryon of Dante's 14th century epic poem Inferno bears no resemblance to any previous writings. Here, Geryon has become the Monster of Fraud, a beast with enormous dragon-like wings with the paws of a bear or lion, the body of a wyvern, and a scorpion's poisonous sting at the tip of his tail, but with the face of an "honest man", bull, ram, lion, or an eagle (similar to a manticore). He dwells somewhere in the shadowed depths below the cliff between the seventh and eighth circles of Hell (the circles of violence and simple fraud, respectively); Geryon rises from the pit at Virgil's call and to Dante's horror Virgil requests a ride on the creature's back. They then board him, and Geryon slowly glides in descending circles around the waterfall of the river Phlegethon down to the great depths to the Circle of Fraud.[6]

Classical literature sources

Chronological listing of classical literature sources for Geryon:

- Hesiod, Theogony 287 ff (Hesiod the Homeric Hymns and Homerica trans. Evelyn-White 1920) (Greek epic poetry C8th or C7th BC)

- Hesiod, Theogony 979 ff

- Pindar, Isthmian Ode 1. 13 ff (trans. Sandys) (Greek lyric poetry C5th BC)

- Scholiast on Pindar, Isthmian Ode 1. 13(15) (The Odes of Pindar trans. Sandys 1915 p. 439)

- Pindar, Fragment 169 (trans. Sandys)

- Herodotus, Histories 4. 8. 1 ff (trans. Godley) (Greek history C5th BC)

- Aeschylus, Agamemnon 869 ff (trans. Buckley) (Greek tragedy C5th BC)

- Aeschylus, Hrakleidai Fragment 37 Scholiast on Aristeides (codex Marcianus 423) (Aeschylus trans. Weir Smtyh, 1926 Vol. II)

- Aeschylus, Prometheus Unbound Fragment 112 (trans. Weir Smyth)

- Scholiast on Aeschylus, Prometheus Unbound Fragment 112 (Aeschylus trans. Weir Smyth 1926 Vol II p. 447)

- Euripides, The Madness of Hercules 421 ff (trans. Way) (Greek tragedy C5th BC)

- Euripides, The Madness of Hercules 1271 ff

- Plato, Gorgias 484b ff (trans. Lamb) (Greek philosophy C4th BC)

- Plato, Euthydemus 299c ff (trans. Lamb)

- Plato, Laws 7. 795c ff (trans. Bury)

- Scholiast on Plato, Timaeus 24E (Platon Samtliche Dialoge, Vol 6 trans. Apelt Hildebrandt Ritter Schneider 1922 p. 148)

- Aristotle, Meteorologica 2. 3 359a 26 ff (ed. Ross trans. Webster) (Greek philosophy C4th BC)

- Aristophanes. Acharnians 1080 ff (trans. Anonymous) (Greek comedy C4th BC)

- Isocrates, Archidamus 6. 19 ff (trans. Norlin) (Greek philosophy C4th BC)

- Isocrates, Helen 24 ff (trans. Norlin) (Greek philosophy C4th BC)

- Pseudo-Aristotle, De Mirabilibus Auscultationibus, 843b 133 (ed. Ross trans. Dowdall) (Greek rhetoric C4th to 3rd BC)

- Pseudo-Aristotle, De Mirabilibus Auscultationibus, 844a

- Lycophron, Alexandra 648 ff (Callimachus and Lycophron Aratus trans. Mair 1921 p. 548 with the scholiast) (Greek poetry C3rd BC)

- Lycophron, Alexandra 1345 ff (Callimachus and Lycophron Aratus trans. Mair 1921 p. 606 with the scholiast)

- Plautus, Aulularia, or The Concealed Treasure, 3. 10 (trans. Riley) (Roman comedy C3rd to C2nd BC)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 8. 4 ff (trans. Oldfather) (Greek history C1st BC)

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 17. 1 ff

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.18. 2 ff

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 24. 2 ff

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 5. 4. 2 ff

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 5. 17. 4 ff

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 5. 24. 3 ff

- Lucretius, Of the Nature of Things 5 Proem 1 (trans. Leonard) (Roman philosophy C1st BC)

- Parthenius, Love Romances 30 (trans. Gaselee) (Greek poetry C1st BC)

- Virgil, The Aeneid 6. 285 ff (trans. Hamilton Bryce) (Roman epic poetry C1st BC)

- Virgil, The Aeneid 7. 662 ff

- Virgil, The Aeneid 8. 201 ff

- Horace, The Odes 2. 14 ff (trans. Conington) (Roman lyric C1st BC)

- Propertius, Elegies 3. 22. 7 ff (trans. Butler) (Latin poetry C1st BC)

- Strabo, Geography 3. 2. 11 (trans. Jones) (Greek geography C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Strabo, Geography 3. 5. 4

- Strabo, Geography 3. 2. 13

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 9. 185 ff (trans. Miller) (Roman poetry C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Ovid, The Heroides 9. 92 ff (trans. Showerman) (Roman poetry C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Ovid, Fasti 1. 543-586 (trans. Frazer) (Roman epic poetry C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Ovid, Fasti 5. 645 ff (trans. Frazer)

- Ovid, The Tristia 4. 7. 16 (trans. Riley) (Roman epigram C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Scholiast on Ovid, The Tristia 4. 7. 16 (Ovid The Fasti, Tristia, Pontic Epistles, Ibis, and Halieuticon trans. Riley 1851 p. 335)

- Livy, The History of Rome 1. 7 ff (trans. Spillan) (Roman history C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Livy, The History of Rome 60 (trans. M'Devitte)

- Fragment, Homerica, The War of The Titans 7 (Hesiod the Homeric Hymns and Homerica, trans. Evelyn-White 1920) (Greek commentary C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Fragment, Alcman, 815 Geryoneis (Greek Lyric trans. Campbell 1991 Vol 3) (Greek commentary C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, The Tale of Geryon, 5 (Lyra Graeca, trans. Edmond 1920 Vol II) (Greek commentary C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, The Tale of Geryon 6

- Fragment, Stesichorus, The Tale of Geryon 8

- Fragment, Stesichorus, The Tale of Geryon 10

- Fragment, Stesichorus, Geryoneis S. 10 (P. Oxy. 2617) (trans. Theoi.com) (Greek commentary C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, Geryoneis S. 11 (P. Oxy. 2617 frr. 13 (a) + 14 +15) (Under the Seams Runs the Pain trans. Carmel 2013) (Greek commentary C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, Geryoneis S. 12 (P. Oxy. 2617 fr. 19 col. ii) (trans. Theoi.com)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, Geryoneis S. 13 (P. Oxy. 2617 fr. 11) (trans. Carmel 2013)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, Geryoneis S. 14 (P. Oxy. 2617 fr. 3) (trans. Theoi.com)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, Geryoneis S. 15 (P. Oxy. 2617 fr. 4) (Greek commentary C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Fragment, Stesichorus, Geryoneis S. 17 (P. Oxy. 2617)

- Fragment, Ibycus, 282A (Greek Lyric trans. Campbell Vol 3) (Greek commentary C1st BC to C1st AD)

- Philippus of Thessalonica, The Twelve Labors of Hercules (The Greek Classics ed. Miller Vol 3 1909 p. 397) (Greek epigrams C1st AD)

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 4. 120 (trans. Rackham) (Roman history C1st AD)

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 231 ff (Seneca's Tragedies, trans. Miller Vol 1 1917 p. 21 with the scholiast) (Roman tragedy C1st AD)

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 486 ff (trans. Miller)

- Seneca, Hercules Furens 1170 ff

- Seneca, Agamemnon 837 ff (trans. Miller)

- Seneca, Hercules Oetaeus 23 ff (trans. Miller)

- Seneca, Hercules Oetaeus 1203 ff

- Seneca, Hercules Oetaeus 1900 ff

- Plutarch, Moralia, The Roman Questions, 267E-F (trans. Babbitt) (Greek philosophy C1st AD to C2nd AD)

- Plutarch, Moralia, Parallel Stories, 315C ff

- Plutarch, Moralia, Precepts of Statecraft, 819D ff (trans. Fowler)

- Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History Bk2 (trans. Pearse) (summary from Photius, Myriobiblon 190) (Greek mythography C1st to C2nd AD)

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, The Library 2. 5. 10 ff (trans. Frazer) (Greek mythography C2nd AD)

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 1. 35. 7-8 (trans. Jones) (Greek travelogue C2nd AD)

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 3. 18. 13

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 4. 36. 3

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 10. 2. 9 ff

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 5. 19. 1

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 10. 17. 5

- Aelian, On Animals 12. 11 (trans. Scholfield) (Greek natural history C2nd AD)

- Suetonius, Tiberius 14 (trans. Thomson) (Roman history C2nd AD)

- Lucian, Hercules 2 ff (trans. Harmon) (Assyrian satire C2nd AD)

- Lucian, The Ignorant Book-collector 14 ff

- Lucian, The Runaways 31 ff

- Lucian, Toxaris, or Friendship 62 ff

- Lucian, The Dance 56 ff

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 0 (trans. Grant) (Roman mythography C2nd AD)

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 30

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 151

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Hygini Astronomica, Liber Secundus, VI Engonasin 10 ff (trans. Bunte)

- Oppian, Cynegetica 2. 109 ff (trans. Mair) (Greek poet C2nd AD)

- Athenaeus, The Banquet of the Learned 8. 38 ff (trans. Yonge) (Greek rhetoric C2nd AD to C3rd AD)

- Athenaeus, The Banquet of the Learned 8. 68 ff

- Athenaeus, The Banquet of the Learned 9. 10 ff

- Athenaeus, The Banquet of the Learned 11. 16 ff

- Athenaeus, The Banquet of the Learned 11. 101 ff

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 5. 4 (trans. Conyreare) (Greek sophistry C3rd AD)

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 5. 5

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 6. 10

- Philostratus, Lives of the Sophists 1. 505 ff (trans. Wright)

- Hippolytus, Philosophumena 5 The Ophite Heresies 25 ( Philosophumena trans. Legge 1921 Vol 1 p. 172) (Christian theology C3rd AD)

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 6. 249 ff (trans. Way) (Greek epic poetry C4th AD)

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Ammianus Marcellinus 15. 9. 5 ff (trans. Rolfe) (Roman history C4th AD)

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Ammianus Marcellinus 15. 10. 9 ff

- Servius, In Vergilii Carmina Commentarii 8. 299 ff (trans. Thilo) (Greek commentary C4th AD to 5th AD)

- Eunapius, Lives of the Philosophers, 487 ff (trans. Wright) (Greek sophistry C4th to C5th AD)

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 25. 236 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic poetry C5th AD)

- Nonnos, Dionysiaca 25. 242 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic poetry C5th AD)

- Nonnos, Dionysiaca 25. 543 ff

- Suidas s.v. Boulei diamachesthai Geruoni tetraptiloi (trans. Suda online) (Greco-Byzantine Lexicon C10th AD)

- Suidas s.v. Geryones

- Suidas s.v. Trikephalos

- First Vatican Mythographer Scriptores rerum mythicarum 68 Geryon et Hercules (ed. Bode) (Greco-Roman mythography C9th AD to C11th AD)

- Second Vatican Mythographer Scriptores rerum mythicarum 132 Geryon (ed. Bode) (Greco-Roman mythography C11th AD)

- Second Vatican Mythographer Scriptores rerum mythicarum 153 Evander 6 ff

- Tzetzes, Chiliades or Book of Histories, Concerning Heracles 2.4 (Story 36) 320-340 (trans. Untila et al.) (Greco-Byzantine history C12 AD)

- Tzetzes, Chiliades or Book of Histories, Concerning Heracles 2.4 (Story 36) 500

- Tzetzes, Chiliades or Book of Histories, Concerning the Trees of Geryon 4.18 (Story 136) 350 ff

- Tzetzes, Chiliades or Book of Histories, An Epistle to Sir John Lachanas, 686 ff

- Tzetzes, Chiliades or Book of Histories, Concerning Cacus 5.5 (Story 21) 99 ff

- Third Vatican Mythographer, Scriptores rerum mythicarum 13. 6 ff (ed. Bode) (Greco-Roman mythography C11th AD to C13th AD)

In medieval Iberian culture

The myth of Geryon is linked to the building of the nations of Spain and Portugal, since he was considered an inhabitant of the Iberian Peninsula.[7]

Medieval authors such as the bishop of Girona Joan Margarit i Pau (1422-1484) or the bishop of Toledo Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada tried to legitimate the resistance of Geryon against the Greek invader.[7]

The Estoria de España of Alfonso X of Castile tells how Hercules killed the giant Geryon, cut his head off and ordered a tower built on it marking his victory. The Tower of Hercules in Coruña, Spain, is actually a working lighthouse rebuilt on a Roman lighthouse.[8]

The Portuguese friar Bernardo de Brito considers the monster a historical invader, ruling despotically over the descendants of Tubal.[7]

See also

- The Cádiz Memorial is a London monument displaying a captured Napoleonic mortar mounted on a dragon inspired by Geryon.

- "Hercules and the Jilt Trip"

- Autobiography of Red, by Anne Carson, a modern re-creation of the myth.

Notes

- ↑ "Geryon". Collins English Dictionary

- ↑ Also Γηρυόνης (Gēryonēs) and Γηρυονεύς (Gēryoneus).

- ↑ The early third-century Life of Apollonius of Tyana notes an ancient tumulus at Gades raised over Geryon as for a Hellenic hero: "They say that they saw trees here such as are not found elsewhere upon the earth; and that these were called the trees of Geryon. There were two of them, and they grew upon the mound raised over Geryon: they were a cross between the spruce and the pine, and formed a third species; and blood dripped from their bark, just as gold does from the Heliad poplar" (v.5).

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony "the triple-headed Geryon".

- ↑ Aeschylus, Agamemnon: "Or if he had died as often as reports claimed, then truly he might have had three bodies, a second Geryon, and have boasted of having taken on him a triple cloak of earth, one death for each different shape."

- ↑ Erytheia, "sunset goddess" and nymph of the island that has her name, is one of the Hesperides.

- ↑ Libya was the generic name for North Africa to the Greeks.

- ↑ Stesichorus, fragment, translated by Denys Page.

- ↑ Pausanias, 10.17.5

References

- ↑ Scholiast on Hesiod's Theogony, referring to Stesichoros' Geryoneis (noted at TheoiProject).

- ↑ Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheke, 2.5.10.

- ↑ P.T. Eden, A Commentary on Virgil: Aeneid VII (Brill, 1975), p. 155 online.

- ↑ Signes gravés sur les églises de l'Eure et du Calvados by Asger Jorn, Volume II of the Bibliotehéque Alexandrie, published by the Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism, 1964, p. 198

- ↑ Denys Page 1973:138-154 gives the fragmentary Greek and pieces together a translation by overlaying the fragments with the account in Bibliotheke. Additional details concerning Geryon follow Page's account.

- ↑ Alighieri, Dante (2002). Inferno. Hollander, Robert and Hollander, Jean (1st Anchor Books ed.). New York: Anchor Books. p. 312–325. ISBN 0385496982. OCLC 48769969. https://archive.org/details/inferno00dant_1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Moreira Fernandes, José Sílvio (2007). "Estrutura e função do mito de Hércules na Monarquia Lusitana de Bernardo de Brito" (in pt). Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em Debate (9): 119–150. ISSN 0874-5498. http://www2.dlc.ua.pt/classicos/hercules.pdf. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ↑ "Tower of Hercules" (in en). https://turismocoruna.com/web/corTurServer.php?idSecweb=321&idFicha=41&id_secPadre=260&idCategoria=176&idSecDescendencia=316.

Further reading

- M.M. Davies, “Stesichoros' Geryoneis and its folk-tale origins”. Classical quarterly NS 38, 1988, 277–290.

- Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red. New York: Vintage Books, 1998. A modern retelling of Stesichoros' fragments.

- P. Curtis: Steschoros's Geryoneis, Brill, 2011.

External links

KSF

KSF