Table of Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Controversy

- 3 Contributors

- 4 Themed and special issues

- 5 Regular sections

- 6 Reception

- 7 Bibliography

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 External links Categories

- "A small obscure magazine published, I think, in Hull and called, would hon. Members believe, Lobster makes a practice of publishing names of gentlemen who are alleged to be members of the security services. That creates danger and I am sure that my right hon. Friend the Member for Old Bexley and Sidcup shares my deep apprehension about that sort of practice being allowed to continue."[44]

- Dan Atkinson,[46] a British journalist and author

- William Blum,[47] American author and historian

- Mike Carlson, broadcaster and writer for The Guardian and the Independent

- Colin Challen,[48] the Member of Parliament for Morley and Rothwell from 2001 until 2010

- Kevin Coogan,[49] American investigative journalist

- Alex Cox,[50] a film-maker

- Mark Curtis,[51] investigative journalist and author

- Anthony Frewin, writer and assistant to Stanley Kubrick

- Robert Henderson,[52] British writer

- Jim Hougan,[53] author of Decadence, Spooks, and Secret Agenda

- John Newsinger,[54] author and professor of history at Bath Spa Univ

- David Osler,[55] a British author and journalist

- Greg Palast,[56] author and a freelance journalist

- Jan Nederveen Pieterse,[57] Professor of Global Studies and Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara

- Dave Renton,[58] historian and political activist

- Paul Rogers,[59] Professor of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford

- Peter Dale Scott,[60] a former English professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a former diplomat

- Michael John Smith,[61] convicted of espionage

- Giles Scott-Smith,[62] Professor of Diplomatic History of Atlantic Cooperation at Leiden University.[63]

- Kenn Thomas,[64] conspiracy theorist, writer, editor & publisher of Steamshovel Press

- Lobster Issue 11

- Lobster Special Issue

- From Lobster 31

- From Lobster 45

- From Lobster 28

- From Lobster 38

- From Lobster 42

- From Lobster 3

- From Lobster 10

- Robert McCrum, "Inside Story: In the lair of the lobster – Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsey edit a left-wing journal that offers succour to conspiracy theorists and keeps the professionals on their toes", The Guardian (London), 31 August 1991

- "Sexed-up files, lies and surveillance tapes ... One man's search to uncover what lies beneath", Hull Daily Mail, 13 July 2007 Friday, page 10

- "Shock Lobster", Sunday Herald, 17 August 2003. Online at U. Utah

- CounterSpy

- CovertAction Quarterly

- Executive Intelligence Review

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Captain Moonlight's Notebook: As pink as two Lobsters", The Independent (London), 14 March 1993, Sunday

- ↑ "Sexed-up files, lies and surveillance tapes ... One man's search to uncover what lies beneath", Hull Daily Mail, 13 July 2007 Friday, page 10

- ↑ Kenn Thomas, Cyberculture Counterconspiracy, publisher Book Tree, 1999, ISBN 1585091251, 9781585091256, 180 pages, page 71

- ↑ Lobster Issue No.1, September 1983, ISSN 0964-0436, which states that it is "a journal/newsletter about intelligence, parapolitics, state structures and so forth"

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 See the Lobster website, retrieved 16 August 2012

- ↑ "Sexed-up files, lies and surveillance tapes.... One man's search to uncover what lies beneath", Hull Daily Mail, Friday 13 July 2007, page 10

- ↑ Steve Beard, Aftershocks: The End of Style Culture, Publisher Wallflower Press, 2002, ISBN 1903364248, 9781903364246, 180 pages, page 66

- ↑ Robin Ramsay, "Kitson, Kincora and counter-insurgency in Northern Ireland", Lobster, Issue 10, January 1986, ISSN 0964-0436.

- ↑ Francesca Klug, The Three Pillars of Liberty: Political Rights and Freedoms in the United Kingdom, Publisher Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0415096413, 9780415096416, 400 pages, page 164

- ↑ For example, by Kevin McNamara M.P., HC Deb 27 November 1986 vol 106 c309W, retrieved 14 August 2012

- ↑ "Contributors", Studies in Intelligence, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Vol. 50, No. 4, 2006, published by the CIA, retrieved 5 January 2012

- ↑ Intelligence Newsletter is now published on the Internet as Intelligence Online by Indigo Publications. "About Us", retrieved 5 January 2012

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hayden B. Peake, The Reader's Guide to Intelligence Periodicals, 1992, published: NIBC Press, pages 86-89

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Richard Norton-Taylor, "Magazine prints security names", The Guardian (London), 29 May 1989

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Thom Burnett, Conspiracy Encyclopedia. New York: Chamberlain Bros. ISBN 1596091568, 978-1843403814. p. 91.

- ↑ See "JFK Newsletters", in the Baylor Collections of Political Materials at Baylor University, retrieved 17 August 2012

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 McCrum, Robert. "In the Lair of the Lobster: Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsey edit a left-wing journal that offers succour to conspiracy theorists and keeps the professionals on their toes." The Guardian (London) (31 Aug. 1991), pp. 12-13.

- ↑ "A review of the (bad) reviews of Smear! Wilson and the Secret State", Lobster Issue 22, November 1991, ISSN 0964-0436, Hull, United Kingdom

- ↑ Steve Dorril and Robin Ramsay (editors), Lobster Issue 1, September 1983, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ Cover, Lobster Issue 5, August 1984, ISSN 0964-0436 (see "Lobster Issues 1-8: 1983-1985")

- ↑ Lobster Issues website, retrieved 15 August 2012

- ↑ Robin Ramsay, "A review of the (bad) reviews of Smear! Wilson and the Secret State" Lobster Issue 20, November 1990, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ "Editorially", Lobster Issue 8, June 1985, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Robin Ramsay, "A short history of Lobster", and "Lobster Credits", and "About the CD-Rom", Lobster online, retrieved 15 August 2012

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 The Feral Beast, "'Lobster' served online", The Independent on Sunday, 13 December 2009, First Edition, page 88

- ↑ "Shock Lobster", Sunday Herald, 17 August 2003. Online at U. Utah

- ↑ "Lobster Plot", Evening Standard (London), 24 June 1993, Thursday, page 8

- ↑ Stephen Dorril (Editor and publisher), Lobster 26 ('93), Holmfirth, West Yorkshire (online)

- ↑ "News" at Rogerdog.co.uk, The Home Page of author Stephen Dorril, retrieved 15 August 2012

- ↑ Kate Smith, "Pelted with cyber-tomatoes", The Guardian, Tuesday 15 July 2008, retrieved 27 December 2012

- ↑ Staff profile – Chris Atton, Edinburgh Napier University, retrieved 27 December 2012

- ↑ Chris Atton, "Parapolitics and Deep Politics" in Alternative literature: a practical guide for librarians, publisher: Gower, 1996, ISBN 0566076659, 9780566076657, 202 pages, page 81

- ↑ Ian McIntyre, "Book Review, Caught in a Lobster pot; 'Smear!' – Stephen Dorril and Robin Ramsay: 4th Estate, 20 pounds", The Independent (London), 9 September 1991, Monday, Editorial p. 19

- ↑ Matt Stephenson, "THE year is 1989. The place is London. A wealthy American begins hearing voices in his head. All day, every day he hears them. He comes to believe that the voices are being beamed into his brain by the CIA or some other secret organisation.", Hull Daily Mail, 26 June 2000, p. 10

- ↑ Richard Keeble, Communication Ethics Today, Publisher Troubador Publishing Ltd, 2006, ISBN 1905237685, 9781905237685, p. 284, page 20

- ↑ Francesca Klug, Keir Starmer, Stuart Weir, The Three Pillars of Liberty: Securing Political Rights and Freedom in the United Kingdom, publisher: Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0415096413, 9780415096416, p. 377, page 153

- ↑ Mr. McNamara, "State Security", HC Deb 27 November 1986 vol 106 cc299-300W

- ↑ Mr. McNamara, "State Security", HC Deb 27 November 1986 vol 106 c309W

- ↑ Tam Dalyell, State Security, HC Deb 15 December 1986 vol 107 c353W

- ↑ "First supplement to A Who's Who of the British Secret State", Lobster Issue 19, May 1990.

- ↑ Stephen Dorril, "Spooks", Lobster Issue 22, November 1991. ISSN 0964-0436.

- ↑ Other articles in the series include: (a) "Forty Years of Legal Thuggery. Part One A to B", Lobster Issue 9, September 1985. (b) Steve Dorril, "British Spooks "Who's Who" part 2", Lobster Issue 10, January 1986. (c) "Intelligence Personnel Named in 'Inside Intelligence'", Lobster Issue 15, February 1988. (d) Stephen Dorril, "Philby naming names: Brief Biographies of those Named in the Above", Lobster Issue 16, June 1988.

- ↑ Angus Young, "A DOZEN British intelligence officers named on the Internet this week were first identified by a Hull-based author 10 years ago", Hull Daily Mail, 17 May 1999.

- ↑ "Mr Witney", HC Deb 21 December 1988 vol 144 cc460-546

- ↑ Robin Ramsay, Politics and Paranoia, Publisher Picnic Publishing, 2008, ISBN 0955610540, 9780955610547, p. 300, page 238

- ↑ e.g., Dan Atkinson, "Challenge to Democracy by Ronald McIntosh" (Book review), Lobster Issue 52, Winter 2006/7, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., William Blum, "United States foreign policy", Lobster Issue 46, Winter 2003, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Colin Challen MP, "The crony capitalists: a fond farewell to some regular guys?", Lobster Issue 56, Winter 2008/9, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Kevin Coogan, "The League of Empire Loyalists and the Defenders of the American Constitution", Lobster Issue 46, Winter 2003, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Alex Cox, "Letter from America", Lobster Issue 31, June 1996, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Mark Curtis, "A 'great venture': overthrowing the government of Iran", Lobster Issue 30, December 1995, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Robert Henderson, "Laissez faire as religion", Lobster Issue 58, Winter 2009/2010, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Jim Hougan, "Mark Felt, Jason Blair and 'Misty Beethoven'", Lobster Issue 50, Winter 2005/6, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., John Newsinger, "The Myth of the SAS", Lobster Issue 30, December 1995, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., David Osler, "New Labour, New Atlanticism: US and Tory intervention in the unions since the 1970s", Lobster Issue 33, Summer 1997, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Gregory Palast, "Systemic Corruption, Systemic Solutions", Lobster Issue 38, Winter 1999, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Jan Nederveen Pieterse, "The Rhodes-Milner Group", Lobster Issue 13, 1987, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Dave Renton, "An Unbiased Watch? the police and fascist/anti-fascist street conflict in Britain, 1945-1951", Lobster Issue 35, Summer 1998, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Paul Rogers, "A note on the British deployment of nuclear weapons in crises – with particular reference to the Falklands and Gulf Wars and the purchase of Trident", Lobster Issue 28, December 1994, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Peter Dale Scott, "The United States and the overthrow of Sukarno, 1965-67", Lobster Issue 20, November 1990, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ Michael John Smith, "In camera injustice", Lobster Issue 52, Winter 2006/7, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ e.g., Giles Scott-Smith, "The Organising of Intellectual Consensus: The Congress for Cultural Freedom and Post-War US-European Relations (Part I)", Lobster Issue 36, Winter 1998/9, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ Prof.dr. G. (Giles) Scott-Smith, at Leiden University Institute for History, retrieved 17 August 2012

- ↑ e.g., "A Letter from Kenn Thomas", Lobster Issue 34, Winter 1998, ISSN 0964-0436

- ↑ Francis Elliott, "New Labour unshelled ", Hull Daily Mail, 1 June 1998, Media, Books, page 14

- ↑ "Multimedia: CD ROM: Lobster", Red Pepper magazine, issue No. 85, July 2001, page 14 (website)

- ↑ Mark Pilkington, "Cracking the secrecy clause", Fortean Times, Issue #145, April 2001, ISSN 0308-5899, page 55

- ↑ "Lobster CD-ROM", Green Anarchist, Issue 63, Summer 2001, page 21

- ↑ "Lobster #40 / Lobster CD", Direct Action magazine, Issue #19, Summer 2001, page 29

- ↑ "Letter from MI5: The spies who have come in from the cold ..", PR Week, 29 July 1993.

- ↑ Tim Pat Coogan, The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace, Publisher Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, ISBN 0312294182, 9780312294182, 496 pages, page 533, note 41.

- ↑ Chris Atton, "Parapolitics and Deep Politics" in Alternative literature: a practical guide for librarians, publisher: Gower, 1996, ISBN 0566076659, 9780566076657, 202 pages, page 138

- Official website

- Catalog of back issues

- Full archive online at Stephen Dorril's Rogerdog.co.uk

Contents

Lobster (magazine)

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

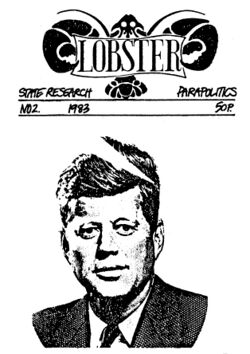

Cover of Lobster's second issue, 1983 | |

| Editor | Robin Ramsay |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Biannual |

| Format | A5 (issues 1–9) A4 (issues 10–57) A4 PDF Online (issue 58+) |

| Circulation | ≈1,200 (1993)[1] 1,300 (2007)[2] |

| Publisher | Lobster |

| Founder | Robin Ramsay Stephen Dorril |

| First issue | 1983 |

| Website | www |

| ISSN | 0964-0436 |

Lobster is a magazine that is interested primarily in the influence of intelligence and security services on politics and world trade, what it calls "deep politics" or "parapolitics". It combines the examination of conspiracy theories and contemporary history.[3][4] Lobster is edited and published in the United Kingdom and has appeared twice a year for 42 years, at first in 16-page A5 format, then as an A4 magazine. Operating on a shoestring, its contributors include academics and others. Since 2009 it is distributed as a free downloadable PDF document.[5]

According to the Hull Daily Mail, Lobster 'investigates government conspiracies, state espionage and the secret service.'[6] In 1986 the magazine scooped mainstream media by uncovering the secret Clockwork Orange operation, implicated in trying to destabilise the British government. Colin Wallace,[7][8] a former British Army Intelligence Corps officer in Northern Ireland, described how he had been instructed to smear leading UK politicians.[9] Questions were asked in the House of Commons and an extended scandal ensued.[10]

The current curator of the CIA Historical Intelligence Collection, Hayden B. Peake,[11] notes that the editors of Lobster see it as "member of the international brotherhood of parapolitics mags," the other members being Geheim (Cologne, Germany), Intelligence Newsletter (Paris, France),[12] and Covert Action Information Bulletin (US), and is "distinctive in its depth of coverage, its detailed documentation, and the absence of the rhetoric".[13]

In 1989, Lobster published names of 1,500 citizens said to be working in intelligence. The magazine was denounced in the House of Commons. The editors replied that all published details could be found in local libraries.[14] The magazine has also carried detailed analysis of fringe and pseudoscientific subjects such as UFOs and remote viewing.[15]

History

Founding

In 1982, an American newsletter about the Kennedy assassination, Echoes of Conspiracy,[16] put Robin Ramsay and Stephen Dorril in touch with each other because of their common interest in the JFK assassination story. A few months later, they decided to launch a magazine, and in September 1983, they published 150 copies of The Lobster priced at 50p.[17] Ramsay later described himself and his associate: "Dorril is a Freudo-anarchist, with Situationist tendencies; and Ramsay is a premature anti-Militant member of the soft old left of the Labour Party".[18]

The inaugural issue stated its aims as "a journal/newsletter about intelligence, parapolitics, state structures and so forth [..] there is no copyright on the material in The Lobster [..] we hope to break even at the present price of 50p, but we may not [..] should appear 6 times a year".[19] From Issue 5 onwards, the cover dropped the definite article and became just "Lobster".[20]

Publishing frequency Lobster dropped to four issues in 1984 and three issues in 1986 and 1987, before settling down as a bi-annual from 1988.[21] The Lobster logo (see illustration), first appeared in issue 20 in November 1990 and was designed by Clive Gringras.[22]

Format and costs

The first 8 issues of Lobster are A5 paper size (148 × 210mm) format, growing to A4 (210 × 297mm) from Issue 9 in September 1985.[23] The magazine was originally typewritten, reduced on a photocopier, pasted-up and printed on a Gestetner off-set litho duplicating machine. Around issue 17, the magazine was type-set on an Amstrad PCW using Wordstream and from Lobster 27, on an AppleMac with Claris Works.[24] Lobster Issue 57 (Summer 2009) was the last hard copy issue.[25] Issue 58 (Winter 2009/2010) was the first available without charge. The magazine is published from Ramsay's home in Hull.[26]

Lobster is published not-for-profit. The Independent on Sunday quoted Ramsay that the magazine ".. always broke even, as I would put the price up if it started losing money. The readers paid whatever I asked", which the newspaper commented "Sounds a fine business model".[25] Robert McCrum in The Guardian quotes Ramsay as boasting that Lobster is "the only left-wing journal to pay for itself".[17]

The Dorril/Ramsay split

In March 1993, The Independent newspaper noted that the founders of Lobster had fallen out, and that "The break between the two men began in December when Ramsay told Dorril he was removing his name from the Lobster masthead and would run the twice-yearly magazine alone."[1] The London Evening Standard reported that Ramsay had told his readers that Dorril also planned to produce a magazine called Lobster.[27] After producing Lobster Issue 25, they each produced their own version of Lobster Issue 26. Dorril recalls a different version of events.[28] Dorril's website indicates that his Lobster Issue 31 (October 1996) was the last published.[29] Alternative media expert[30] and Professor of Media and Culture at Edinburgh Napier University, Chris Atton,[31] notes that Dorril's Lobster concentrates on the activities of the British and US security services, while Robin Ramsay's Lobster casts its net wider to encompass histories of fascism, the JFK assassination, the Lockerbie bombing and the military's medical experiments on service personnel.[32]

Name

The name of the magazine, "Lobster", has attracted multiple interpretations. Dorril recalls that "We wanted the magazine to sound not pompous, and as a teenager, he would invent names for punk rock groups. 'Lobster' was just one of his favourites."[17] Ramsay recalls that "The name "Lobster" was Steve Dorril's choice. I couldn't think of an alternative and I didn't think the name mattered. As far as I know it had no connotations for Dorril; indeed as I remembered it, the absence of connotations was part of its appeal."[24]

Controversy

Operation Clockwork Orange, Colin Wallace and Fred Holroyd

Lobster published the first account of the Colin Wallace affair,[33][34] also known as Operation Clockwork Orange, about the plot by disaffected members of Britain's Security Service, MI5, to destabilise the Harold Wilson Labour Government,[35] and to smear politicians such as former Tory prime minister Edward Heath.[36] The editors of Lobster described the revelations as Britain's Watergate and the biggest story since World War Two. The revelations were subsequently confirmed by former MI5 officer Peter Wright in his book Spycatcher.[17]

Political fallout

In late 1986, questions were asked in the UK Parliament concerning the matters in Lobster. Then Labour Party Member of Parliament for Hull North, Kevin McNamara, brought up the issue in the House of Commons, asking the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, to refer the matter to the Security Commission,[37] and asking then Attorney-General and Conservative MP Michael Havers, to ask the Director of Public Prosecutions to investigate allegations published in Lobster and prosecute Colin Wallace for revealing details of secret service operations against Her Majesty's Government.[38] Both declined. Two weeks later, Labour MP Tam Dalyell asked the Prime Minister why she would not refer the matter to the Security Commission, but she said that she had nothing more to add.[39]

Who's Who of the British Secret State

In 1989, British journalist Richard Norton-Taylor reported in The Guardian newspaper, that Lobster was planning to publish "a list of the names and brief biographical details of more than 1,500 past and present officials involved, according to the publishers, in covert activities".[14] A year later the article appeared in Lobster Issue 19,[40] and another appeared 18 months later.[41][42] Although The Guardian noted that the Government was considering making the publication of such names a criminal offence, then Lobster co-editor Stephen Dorril noted that "All the names and details .. have been compiled by research in their local libraries or have already appeared in published books. 'No inside knowledge or breach of official secrets was needed'"[14] 10 years later, Ramsay was quoted in the Hull Daily Mail, that "At the time it was a way of sticking two fingers up at the Government".[43]

House of Commons criticism

Subsequently, Lobster was denounced in the British Parliament.[15] Then Conservative Party Member of Parliament for Wycombe, Ray Whitney, criticised the publication of the names in the House of Commons on 21 December 1988 in a debate on a proposed Official Secrets Bill, when he commented that:

In his book, Politics and Paranoia, Ramsay criticised Whitney's role as the head of the Foreign Office's Information Research Department which Ramsay described as the "State's official, anti-left psy-war outfit", and had omitted to tell the Commons before denouncing him.[45]

Contributors

In addition to co-founders Robin Ramsay and Stephen Dorril, contributors have included:

Themed and special issues

Lobster has published a couple of themed or special issues, including:[5]

|

|

(April 1986) | Wilson, MI5 and the Rise of Thatcher: Covert Operations in British Politics 1974-1978 |

|

|

(1996) | The Clandestine Caucus. Anti socialist campaigns and operations in the British Labour Movement since the war |

Regular sections

A number of regular sections have appeared in Lobster over the years:[5]

| When started | Section name | Section description |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Parish notices | name checks, thanks, and updates on contributors |

|

|

Re: | a round-up of news, mainly on 'fringe' issues |

|

|

View from the Bridge | an editorial news section, by Ramsay |

|

|

Historical notes | A 'long view' of events, by Scott Newton. |

|

|

Tittle-tattle | the self-effacing title of John Burne's column |

|

|

Reviews | mainly of books, sometimes other media, by various contributors |

|

|

Letters |

Reception

In 1998, the Hull Daily Mail described the magazine as "a tiny but influential fringe political journal".[65] In 2001, the magazine Red Pepper wrote that Lobster ".. succeeds on the quality of its writing... articles are well researched... human, passionate and honest...",[66] the Fortean Times (who also syndicated a regular Lobster column by Ramsay) wrote that it was "... immensely engrossing reading, ...an essential purchase for anyone interested in the machinations of the secret state",[67] Green Anarchist magazine wrote that Lobster is "... an invaluable resource, and deserves to be widely read and much studied",[68] and Direct Action magazine described it as "a good read ... very revealing and worth it, just for the pub talk".[69]

Journalist Robert McCrum in The Guardian describes Lobster as ".. a left-wing journal that offers succour to conspiracy theorists [..] a brave, bright beacon, a Quixotic piece of typically English amateurism that keeps the professionals on their toes".[17] The Independent newspaper has described it as a "delightful and worthwhile publications, more footnote than story, that [..] delivers a comprehensive picture of a clandestine world which the Establishment would prefer remained secret".[1]

Trade Magazine PRWeek describes Lobster as a "Hull-based intelligence magazine and conspiracy theorists' bible",[70] and the Conspiracy Encyclopedia described it as "the most influential publication in the parapolitical underground".[15] Irish historical writer, Tim Pat Coogan, in discussing a TV programme about Captain Fred Holroyd in relation to the Collin Wallace affair, noted that "some of the best writing on the Holroyd case is contained in smaller journals published contemporaneously, notably Lobster, Private Eye, and, in particular [Duncan] Campbell's own series [..] in the Statesman".[71]

Professor of Media and Culture at Edinburgh Napier University, Chris Atton, notes that a reference at the end of an article in Lobster led to the founding of the activist librarians' group Information for Social Change.[72] CIA curator, Hayden B. Peake notes that a British journalist described "much of its content its impenetrable", but that it was also intriguing.[13]

Bibliography

See also

References

External links

| 0.00      (0 votes) (0 votes) |

KSF

KSF