Poniatowski gems

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

The Poniatowski gems are a collection of over 2,600 engraved gems commissioned by Prince Stanisław Poniatowski (1754–1833), a wealthy Polish nobleman, and passed off by him as genuine classical pieces. By the time of his death in 1833 it was becoming clear to scholars that the gems were instead early 19th-century neoclassical forgeries. The gems in Poniatowski's collection were auctioned as authentic antiques in 1839, but the auction was a failure, and the surrounding controversy depressed collector interest in engraved gems for years afterward. The gems were scattered, and many have been lost or mislaid. Today they are appreciated as excellent examples of neoclassical gem carving.

History

Poniatowski was "an avid collector of art, ... once considered the richest man in Europe".[2] He inherited approximately 154 antique gems from his uncle, King Stanisław August Poniatowski of Poland, who died in 1798.[3] He augmented this collection with over 2,600[4] forgeries by contemporary carvers, in a florid classicizing style and in most cases signed with ancient names,[2][3][5] while claiming publicly that the works were genuine antiquities.[5] The gems depict scenes from mythology, including the works of Homer, Virgil, and Ovid; some scenes of historical events; and portraits of a wide variety of ancient Greek and Roman figures.[4] Poniatowski published a catalog of this work c. 1830 with further information in two following volumes (Poniatowski c. 1830, 1832, 1833).

Although Giovanni Pichler has been suggested as one of the carvers,[3] the date of Pichler's death in 1791 makes this unlikely.[6] Other carvers include Giovanni Calandrelli – nearly 300 of whose preliminary drawings for the gems are in the collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin[7] – Giuseppe Girometti (it), Niccolò Cerbara (it), Tommaso Cades, and Antonio Odelli.[8] Because the gems were unsigned or signed with fake signatures, most have not been attributed to a known artist, and probably never will be with certainty.[4]

Already, by the early 1830s, scholars began pointing out problematic issues with the style and provenance of these works.[2] Poniatowski presented a set of 419 plaster impressions of his collection to the King of Prussia which now form the Daktyliothek Poniatowski in Berlin;[5] Ernst Heinrich Toelken, director of Antikensammlung Berlin's Antiquarium, declared them to be fakes on the basis that the signatures of ancient artists from very different times were found on gems in too consistent a style, but wrote admiringly that "The impressions are indeed the most beautiful you can expect to see in art."[4]

After Poniatowski died in 1833, his collection was put up for auction in 1839 by Christie's in London (Christie & Manson 1839).[5] The auction turned out disastrously: half the collection remained unsold,[2] and the remaining pieces fetched prices much lower than their estimates (and lower than the value of an unforged work of Pichler's).[3] The fiasco caused collectors' interest in engraved gems, previously a popular field, to drop more generally for many years.[2]

John Tyrrell, former private secretary to Sir George Nugent[9] acquired the unsold items as an investment, and wound up with 1,140 of the gems.[10][4][11] Tyrrell published his own catalog (Prendeville Maginn), including "poetical illustrations of the subjects". Tyrrell made plaster impressions of the collected gems for sale, and many of these were photographed and published (Prendeville & Maginn 1857, 1859) in an illustrated version of Tyrrell's original catalog.

Tyrrell hired scholar Nathaniel Ogle to examine the gems and write an introductory essay to his 1841 catalog, but when Ogle concluded that many of the gems had been produced recently, Tyrrell left the essay out, and instead commissioned impoverished classical scholar James Prendeville and writer William Maginn to write the essay.[13] In 1842 Ogle anonymously published a version of his essay in the British and Foreign Review, to which Tyrrell responded, in an angry letter, that "it is not probable that a nobleman of [Poniatowski's] high character and honour would have asserted that which he did not believe to be true."[14][15] The feud continued, leading to Tyrrell publishing a 55-page essay defending the gems' provenance and attacking Ogle's motives.[16]

Both the gems auctioned by Christie's and those acquired by Tyrrell were subsequently scattered, and many have been lost or mislaid.[2][5] Oxford University's Classical Art Research Centre, formerly the Beazley Archive, has gathered a comprehensive online database of the available provenance and images of gems from the Poniatowski collection.[4] Several works in museums, reputed to be Poniatowski gems, have been revealed on closer inspection to be replicas of the Poniatowski gems: forgeries of forgeries.[2]

For over a century, the Poniatowski gems were scorned as relatively worthless forgeries, but in recent decades have been reinterpreted and reassessed, and are now desirable collectors' items in their own right; at auction individual gems fetch £1,500–3,000, and a ring with a gem depicting Hercules sold for £8,125.[17]

Individual pieces

The Victoria and Albert Museum holds several pieces from the Poniatowski collection, depicting Socrates, Apollo and Daphne, Venus and Aeneas, Pluto and Peleus, Bacchus and Ino, Theseus, Erechtheus, and several scenes from the Trojan war.[18]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art holds several pieces from the Poniatowski collection[19], as does the British Museum.[20]

The Royal Society bought 5 gems at the 1839 auction, representing Euclid, Thales, Archimedes, Aristides and Priam, for prices ranging from £1 10s to £4 4s each, and still holds them today.[11]

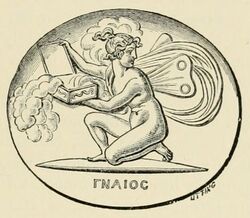

An engraved amethyst ring signed ΓΝΑΙΟϹ (Gnaios), showing Mark Antony in profile, was in 1968 published and praised by gem expert John Boardman,[22] and was subsequently widely reproduced in books as an ancient Roman masterpiece. The ring was acquired in 2001 by the J. Paul Getty Museum, and in 2009 exhibited as an antique. When archaeologist Gertrud Platz (de) saw it, having just written a book about Poniatowski gem engraver Giovanni Calandrelli, she recognized it from a 19th-century plaster impression she had seen among the Poniatowski collection. Platz located photographs of the impression and a page in Calandrelli's notebook listing a gem he made of Mark Antony signed Gnaios. In fact, the "Gnaios" ring was a Poniatowski gem by Calandrelli; Getty curator Kenneth Lapatin tracked down the ring's full provenance.[21][8]

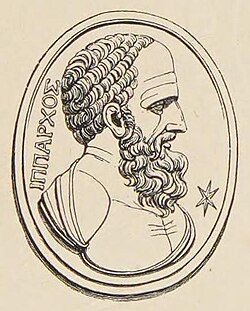

Poniatowski's collection included an amethyst depicting Hipparchus with a star and the subject's name, which was included in Christie's 1939 auction.[23] Astronomer William Henry Smyth acknowledged in 1842 making an impression of "the head of Hipparchus, from the Poniatowski-gem, intended as a vignette illustration of his work".[24] His 1844 book, A Cycle of Celestial Objects, used exactly such a vignette on its title page.[25] This image has subsequently been repeatedly copied and reproduced, including on a 1965 Greek postage stamp commemorating the Eugenides Planetarium in Athens.[26]

The National Museum in Kraków holds two pieces that appear to be replicas or forgeries of the Poniatowski gems, rather than the original gems themselves. One of them, in agate, depicts Hebe as a young woman wearing a chiton with her hair in a bun, pouring wine or nectar from a jug into a cup held by Jupiter, as a half-undressed old man, set in scenery of clouds. It appears to be a crude copy of a sardonyx piece whose plaster cast is held at the University of Oxford, missing its forged signature ("Chromios") and some details in the carving. Another piece in the museum, also likely a copy of a Poniatowski gem, consists of a red jasper stone, carved with a snake with a lion's head and the lettering "vot sol cer", set in a bronze ring.[2]

Catalogs

- Poniatowski, Stanislas (c. 1830), Catalogue des pierres gravées antiques de S. A. le Prince Stanislas Poniatowski, 1, Florence: Guillaume Piatti, https://polona.pl/preview/2aab1313-ee74-4932-b53a-f37c66aa49c0

- Poniatowski, Stanislas (1832), Catalogue des pierres gravées antiques de S. A. le Prince Stanislas Poniatowski, 2, Florence: Guillaume Piatti, https://polona.pl/item-view/7bef7420-ff02-40d6-913d-d7ccb1d3a0a0

- Poniatowski, Stanislas (1833), Catalogue des pierres gravées antiques de S. A. le Prince Stanislas Poniatowski, 3, Florence: Guillaume Piatti, https://polona.pl/item-view/7f06b3df-503a-43d8-b2d7-7d9661255993

- Christie, George Henry; Manson, William (1839), A catalogue of the very celebrated collection of antique gems of the Prince Poniatowski, deceased : which will be sold by auction, by Messrs. Christie and Manson, at their Great Room, 8, King Street, St. James's Square, on Monday, April the 29th, 1839 and following days, at one o'clock precisely each day., London: W. Clowes and Sons

- Prendeville, James; Maginn, William (1841), An historical and descriptive account of the famous collection of antique gems possessed by the late Prince Poniatowski. Accompanied by poetical illustrations of the subjects, from classical authors, with an essay on ancient gems and gem-engraving, London: Henry Graves, https://archive.org/details/AnHistoricalAndDescriptiveAccountOfTheFamousCollectionOfAntiqueGems/

- Prendeville, James; Maginn, William (1857), Photographic facsimiles of the antique gems formerly possessed by the late Prince Poniatowski, 1st series, London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts

- Prendeville, James; Maginn, William (1859), Photographic facsimiles of the antique gems formerly possessed by the late Prince Poniatowski, 2nd series, London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, https://archive.org/details/PhotographicFacsimilesOfTheAntiqueGemsFormerlyPossessedByTheLate/prendeville-j-photographic-1859-RTL012924/

- Wagner, Claudia, Poniatowski Gems Database, Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford, https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/carc/gems/The-Poniatowski-Collection

References

- ↑ attributed to Calandrelli, Giovanni (c. 1820), "Zeus and Kapaneus", signed ΔΙΟϹΚΟΥΡΙΔΟΥ (Dioskouridou), engraved cornelian, 3.4 × 3.9 × 0.3 cm (1-5/16 × 1-9/16 × 1/8 in.), J. Paul Getty Museum No. 83.AL.257.9, CARC:T561

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Gołyźniak, Paweł (December 2016), "The Impact of the Poniatowski Gems on Later Gem Engraving", Studies in Ancient Art and Civilisation 20: 173–192, doi:10.12797/saac.20.2016.20.11

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Wheatley, H. B. (December 1884), "Poniatowski gems", The Antiquary 10: 279, ProQuest 6686976

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Wagner, Claudia (2007). "Imagines: La Antigüedad en las Artes Escénicas y Visuales". in Castillo, Pepa; Knippschild, Silke; García Morcillo, Marta et al.. International Conference at Logroño, 22–24 October 2007. Universidad de la Rioja. pp. 565–572.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Wagner, Claudia, The Poniatowski Collection of Gems: Introduction, Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford, https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/carc/gems/The-Poniatowski-Collection/Introduction, retrieved 2023-07-22

- ↑ Pon, Lisa (March 2004), "The Pleasures of Antiquity: Gertrud Seidmann welcomes Jonathan Scott's masterly survey of British collectors of Greek and Roman antiquities", Apollo 159 (505), https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA114477254&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=fulltext&issn=00036536&p=AONE&sw=w&casa_token=dNveSPuwkfMAAAAA:XYI68VVC2JaNe7pR8hESiY3PItpVtYofC7OcN8n2eH2ZFS9rBe2Vj7cqDMnDuS39EylY0Z1-eRaIegorRk4

- ↑ Platz-Horster, Gertrud (2003), "Zeichnungen und Gemmen des Giovanni Callandrelli", in Willers, D.; Raselli-Nydegger, L. (in de), Im Glanz der Götter und Heroen: Meisterwerke antiker Glyptik aus der Stiftung Leo Merz, Mainz, pp. 49–62 Platz-Horster, Gertrud (2005), L'antica maniera : Zeichnungen und Gemmen des Giovanni Calandrelli in der Antikensammlung Berlin, Berlin: Dumont L'antica maniera: Drawings and Cameos by Giovanni Calandrelli, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 2005, https://www.smb.museum/en/exhibitions/detail/lantica-maniera/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lapatin, Kenneth (2022), "The Getty Gnaios: A love story", Journal of the History of Collections 34 (1): 51–70, doi:10.1093/jhc/fhaa049

- ↑ Nugent, Lady Maria; Wright, Philip (1966), Lady Nugent's Journal of her residence in Jamaica from 1801 to 1805, Institute of Jamaica, pp. 281

- ↑ Rambach, Hadrien J. (2014), "The gem collection of Prince Poniatowski", American Numismatic Society Magazine 13 (2): 34–49, https://numismatics.org/wp-content/uploads/Summer2014.pdf#page=18

- ↑ 11.0 11.1

Roos, Anna Marie (2019), "Object biographies and interdisciplinarity", Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 73 (3): 279–283, doi:10.1098/rsnr.2019.0016

"Intaglio seals", Royal Society MOB/60, "Five gold mounted oval cornelian and chalcedony intaglios carved with antique profiles, inscribed in Greek. They represent Euclid, Thales, Archimedes, Aristides and Priam. Together with a blue velvet lined box, and a box of 9 wax impression of the seals in circular wooden cases (some cases damaged or incomplete)"

- ↑ King, Charles William (1885). Handbook of Engraved Gems (2nd ed.). London: George Bell and Sons. pp. viii. https://archive.org/details/handbookofengrav00king/page/n13/mode/2up.

- ↑ Latané, David E. (2016), William Maginn and the British Press: A Critical Biography, Routledge, pp. 292, ISBN 9781134767298, https://books.google.com/books?id=t_mNCwAAQBAJ

- ↑ Thompson, Erin L. (2016), Possession: The Curious History of Private Collectors from Antiquity to the Present, Yale University Press, pp. 74–75, ISBN 9780300221008, https://books.google.com/books?id=QLEODAAAQBAJ&pg=PA74

- ↑ "Catalogue des Pierres Gravées Antiques de S.A. Le Prince Poniatowski", British and Foreign Review 13 (25): 66–91, 1842, https://books.google.com/books?id=4PtSAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA66 "The Poniatowski Gems", British and Foreign Review 13 (26): 542–545, 1842, https://books.google.com/books?id=mTFLk_uvf8kC&pg=PA542

- ↑ Tyrrell, John (1842), Remarks Exposing the Unworthy Motives and Fallacious Opinions of the Writer of the Critiques on The Poniatowski Collection of Gems Contained in "The British and Foreign Review" and "The Spectator", H Graves and Co & Smith, Elder, and Co, https://books.google.com/books?id=gxJuBQMb47wC

- ↑ Arkell, Roland (12 March 2022), "98 ways to restore Poniatowski's reputation", Antiques Trade Gazette (2533), https://www.antiquestradegazette.com/print-edition/2022/march/2533/feature/98-ways-to-restore-poniatowski-s-reputation/

- ↑ Items in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum: Trojan war scenes: Gods and mortals:

- ↑ Poniatowski gems in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Items listed with provenance from Poniatowski's collection but labeled as "a fake...similar in style" to the Poniatowski gems:

- The ghost of Creusa disappearing from Aeneas near the burning wall of Troy

- Theseus restoring Helen to the brothers Castor and Pollux

- Minerva throwing her aegis over Achilles

- Jason pacifying the dragon

- Diana protecting Erigone from the fury of Orestes

- Hermione invoking Minerva

- Chryseis with an attendant bearing presents, praying to Menelaus to restore his daughter

- ↑ Items in the collection of the British Museum:

- ↑ 21.0 21.1

Calandrelli, Giovanni (c. 1820), "Amethyst intaglio depicting Mark Antony", signed ΓΝΑΙΟϹ (Gnaios), J. Paul Getty Museum, No. 2001.28.1, CARC:1839-1772

Jaskol, Julie (Summer 2021), "A Gem of a Mystery: Curator Kenneth Lapatin sleuths out the truth about the Getty Gnaios", Getty Magazine: 20–23 (magazine PDF), https://www.getty.edu/news/a-gem-of-a-mystery/

- ↑ Engraved Gems. The Ionides Collection, London: Thames & Hudson, 1968, pp. 19, 27-28, and 93-94, no. 18, ill

- ↑ "Head of Hipparchus", CARC:1839-881, described in Poniatowski's catalog (VIII.2.60, vol. 1, p. 105, vol. 2, p. 52) and included in Christie's 1839 auction (No. 881), with whereabouts since unknown.

From Poniatowski (1833), p. 52: "... Dans le champ de cette pierre on voit une étoile et en beaux caractères le nom du sujet. Améthyste." [In the field of this stone we see a star and in beautiful characters the name of the subject. Amethyst.]

- ↑ "Stated Meeting, September 12, 1842", Bulletin of the Proceedings of the National Institute for the Promotion of Science 3: 258, 1845, https://archive.org/details/bulletinofprocee01usan/page/258/

- ↑ Smyth, William Henry (1844), A Cycle of Celestial Objects, 2, John W. Parker, https://archive.org/details/cycleofcelestial02smytrich/page/n10/mode/1up

- ↑ Wilson, Robin (December 1989), "Stamp corner", The Mathematical Intelligencer 11 (1): 72, doi:10.1007/bf03023779

|

KSF

KSF