Prayer, meditation and contemplation in Christianity

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

Prayer has been an essential part of Christianity since its earliest days. Prayer is an integral element of the Christian faith and permeates all forms of Christian worship.[1][2] Prayer in Christianity is the tradition of communicating with God, either in God's fullness or as one of the persons of the Trinity.[1]

In the early Church worship was inseparable from doctrine as reflected in the statement: lex orandi, lex credendi, i.e. the law of belief is the law of prayer.[3] The Lord's Prayer was an essential element of the meetings of early Christians, and over time a variety of Christian prayer emerged.[4][5]

As early as the 2nd century, Christians indicated the eastward direction of prayer by placing a Christian cross on the eastern wall of their house or church, prostrating in front of it as they prayed at seven fixed prayer times.[6][7][8]

Christian prayers are diverse and may vary among Christian denominations. They may be public prayers (e.g. as part of liturgy) or private prayers by an individual (e.g. praying the seven canonical hours with a breviary).[1] Prayers may be performed as adoration, confession, thanksgiving, and supplication (abbreviated as ACTS).[9][2][10]

A broad, three stage hierarchical characterization of prayer begins with vocal prayer, then moves on to a more structured form in terms of Christian meditation, and finally reaches the multiple layers of contemplative prayer.[11][12] Contemplative prayer follows Christian meditation and is the highest form of prayer which aims to achieve a close spiritual union with God. Both Eastern and Western Christian teachings have emphasized the use of meditative prayers as an element in increasing one's knowledge of Christ.[13][14][15][16]

Development of the three stages of prayer

Early Christianity

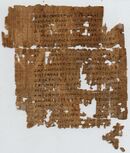

Prayer and the reading of Scripture were important elements of Early Christianity. In the early Church worship was inseparable from doctrine as reflected in the statement: lex orandi, lex credendi, i.e. the law of belief is the law of prayer.[3] Early Christian liturgies highlight the importance of prayer.[17]

The Lord's Prayer was an essential element in the meetings held by the very early Christians, and it was spread by them as they preached Christianity in new lands.[4] Over time, a variety of prayers were developed as the production of early Christian literature intensified.[10]

By the 3rd century Origen had advanced the view of "Scripture as a sacrament".[18] Origen's methods of interpreting Scripture and praying on them were learned by Ambrose of Milan, who towards the end of the 4th century taught them to Saint Augustine, thereby introducing them into the monastic traditions of the Western Church thereafter.[19][20]

Early models of Christian monastic life emerged in the 4th century, as the Desert Fathers began to seek God in the deserts of Palestine and Egypt.[21][22] These early communities gave rise to the tradition of a Christian life of "constant prayer" in a monastic setting which eventually resulted in meditative practices in the Eastern Church during the Byzantine period.[22]

Meditation in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, the monastic traditions of both Western and Eastern Christianity moved beyond vocal prayer to Christian meditation. These progressions resulted in two distinct and different meditative practices: Lectio Divina in the West and hesychasm in the East. Hesychasm involves the repetition of the Jesus Prayer, but Lectio Divina uses different Scripture passages at different times and although a passage may be repeated a few times, Lectio Divina is not repetitive in nature.[22][23]

In the Western Church, by the 6th century, Saint Benedict and Pope Gregory I had initiated the formal methods of scriptural prayer called Lectio Divina.[24] With the motto Ora et labora (i.e. pray and work), daily life in a Benedictine monastery consisted of three elements: liturgical prayer, manual labor and Lectio Divina, a quiet prayerful reading of the Bible.[25] This slow and thoughtful reading of Scripture, and the ensuing pondering of its meaning, was their meditation.[26]

Early in the 12th century, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux was instrumental in re-emphasizing the importance of Lectio Divina within the Cistercian order.[27] Bernard also emphasized the role of the Holy Spirit in contemplative prayer and compared it to a kiss by the Eternal Father which allows a union with God.[28]

The progression from Bible reading, to meditation, to loving regard for God, was first formally described by Guigo II, a Carthusian monk who died late in the 12th century.[29] Guigo II's book The Ladder of Monks is considered the first description of methodical prayer in the western mystical tradition.[30]

In Eastern Christianity, the monastic traditions of "constant prayer" that traced back to the Desert Fathers and Evagrius Pontikos established the practice of hesychasm and influenced John Climacus' book The Ladder of Divine Ascent by the 7th century.[31] These meditative prayers were promoted and supported by Saint Gregory Palamas in the 14th century.[15][22]

From meditation to contemplative prayer

In the Western Church, during the 15th century, reforms of the clergy and monastic settings were undertaken by the two Venetians, Lorenzo Giustiniani and Louis Barbo. Both men considered methodical prayer and meditation as essential tools for the reforms they were undertaking.[32] Barbo, who died in 1443, wrote a treatise on prayer titled Forma orationis et meditionis otherwise known as Modus meditandi. He described three types of prayer; vocal prayer, best suited for beginners; meditation, oriented towards those who are more advanced; and contemplation as the highest form of prayer, only obtainable after the meditation stage. Based on the request of Pope Eugene IV, Barbo introduced these methods to Valladolid, Spain and by the end of the 15th century they were being used at the abbey of Montserrat. These methods then influenced Garcias de Cisneros, who in turn influenced Ignatius of Loyola.[33][34]

The Eastern Orthodox Church has a similar three level hierarchy of prayer.[35][36] The first level prayer is again vocal prayer, the second level is meditation (also called "inward prayer" or "discursive prayer") and the third level is contemplative prayer in which a much closer relationship with God is cultivated.[35]

Hierarchy of prayer forms

Prayer

Prayer is an integral element of the Christian faith and permeates all forms of Christian worship.[1][2] Prayer in Christianity is the tradition of communicating with God, either in God's fullness or as one of the persons of the Trinity.[1] Christian prayers are diverse and may vary among Christian denominations. They may be public prayers (e.g. as part of liturgy) or private prayers by an individual.[1]

The most common prayer among Christians is the Lord's Prayer, which according to the gospel accounts (e.g. Matthew 6:9-13) is how Jesus taught his disciples to pray.[37] The Lord's prayer is a model for prayers of adoration, confession and petition in Christianity.[37]

The first centuries of Christianity witnessed an intense growth in religious literature and these often included prayers.[10] The prayers recorded in early Christian literature can be categorized into six types: petition (including intercession), thanksgiving, blessing (or benediction), praise, confession and finally a small number of lamentations.[10] The first five of these types have persisted throughout the centuries and been expressed in a large number of Christian prayers.[2] However some prayers may combine some of these forms, e.g. praise and thanksgiving, etc.[2][10]

Meditation

Christian meditation is a structured attempt to get in touch with and deliberately reflect upon the revelations of God.[38] The word meditation comes from the Latin word meditārī, which has a range of meanings including to reflect on, to study and to practice. Christian meditation is the process of deliberately focusing on specific thoughts (such as a bible passage) and reflecting on their meaning in the context of the love of God.[39]

In the 20th century the practice of Lectio Divina moved out of monastic settings and reached lay Christians in the Western Church.[40] Separately, among Roman Catholics, meditation on the Rosary remains one of the most widespread and popular spiritual practices.[41]

While meditation in the Western Church was being built on the foundations of Lectio Divina, a different form of meditative practice emerged within Eastern Christianity during the Byzantine period, as the practice of hesychasm gained a following, specially on Mount Athos in Greece. Hesychasm was promoted by Saint Gregory Palamas in the 14th century and remains a part of Eastern Christian spirituality.[15][42]

Both Eastern and Western Christian teachings have emphasized the use of Christian meditation as an element in increasing one's knowledge of Christ.[13][14][15][16] Christian meditation aims to heighten the personal relationship based on the love of God that marks Christian communion.[43][44] It is the middle level in a broad three stage characterization of prayer: it involves more reflection than first level vocal prayer, but is more structured than the multiple layers of contemplation in Christianity.[11]

Contemplation

At times there may be no clear-cut boundary between Christian meditation and Christian contemplation, and they overlap. Meditation serves as a foundation on which the contemplative life stands, the practice by which someone begins the state of contemplation.[45]

In discursive meditation, mind and imagination and other faculties are actively employed in an effort to understand our relationship with God.[46][47] In contemplative prayer, this activity is curtailed, so that contemplation has been described as "a gaze of faith", "a silent love".[48]

See also

- Canonical hours

- Christian devotional literature

- Jesus Prayer

- Prayer in the New Testament

- Roman Catholic prayer

- Roman Catholic prayers to Jesus

- Washing before Christian prayer

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Christianity: an introduction by Alister E. McGrath 2006 ISBN 1-4051-0901-7 pages 296-297

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Foundations of Christian Worship by Susan J. White 2006 0664229247 ISBN pages 27-31

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Formation of Christian Doctrine by Malcolm B. Yarnell 2007 ISBN 0-8054-4046-1 page 147

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The Lord's Prayer in the Early Church by Frederic Henry Chase 2004 ISBN 1-59333-275-0 pages 13-15

- ↑ Philip Zaleski, Carol Zaleski (2005). Prayer: A History. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 0-618-15288-1. https://archive.org/details/prayerhistory00zale.

- ↑ Danielou, Jean (2016). Origen. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4982-9023-4. "Peterson quotes a passage from the Acts of Hipparchus and Philotheus: "In Hipparchus's house there was a specially decorated room and a cross was painted on the east wall of it. There before the image of the cross, they used to pray seven times a day ... with their faces turned to the east." It is easy to see the importance of this passage when you compare it with what Origen says. The custom of turning towards the rising sun when praying had been replaced by the habit of turning towards the east wall. This we find in Origen. From the other passage we see that a cross had been painted on the wall to show which was the east. Hence the origin of the practice of hanging crucifixes on the walls of the private rooms in Christian houses. We know too that signs were put up in the Jewish synagogues to show the direction of Jerusalem, because the Jews turned that way when they said their prayers. The question of the proper way to face for prayer has always been of great importance in the East. It is worth remembering that Mohammedans pray with their faces turned towards Mecca and that one reason for the condemnation of Al Hallaj, the Mohammedan martyr, was that he refused to conform to this practice."

- ↑ Kalleeny, Tony. "Why We Face the EAST". Orlando: St Mary and Archangel Michael Church. https://www.suscopts.org/mightyarrows/east.html. Retrieved 6 August 2020. "Christians in Syria as well, in the second century, would place the cross in the direction of the East towards which people in their homes or churches prayed."

- ↑ Storey, William G. (2004). A Prayer Book of Catholic Devotions: Praying the Seasons and Feasts of the Church Year. Loyola Press. ISBN 978-0-8294-2030-2. "Long before Christians built churches for public prayer, they worshipped daily in their homes. In order to orient their prayer (to orient means literally "to turn toward the east"), they painted or hung a cross on the east wall of their main room. This practice was in keeping with ancient Jewish tradition ("Look toward the east, O Jerusalem," Baruch 4:36); Christians turned in that direction when they prayed morning and evening and at other times. This expression of their undying belief in the coming again of Jesus was united to their conviction that the cross, "the sign of the Son of Man," would appear in the eastern heavens on his return (see Matthew 24:30)."

- ↑ Pokorsky, Rev Jerry J. Pokorsky (31 January 2016). "Balancing ACTS at Mass". The Catholic Thing. https://www.thecatholicthing.org/2016/01/31/balancing-acts-at-mass/. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 The Encyclopedia of Christian Literature, Volume 1 by George Thomas Kurian 2010 ISBN 0-8108-6987-X pages 135-138

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Simple Ways to Pray by Emilie Griffin 2005 ISBN 0-7425-5084-2 page 134

- ↑ "The Christian tradition comprises three major expressions of the life of prayer: vocal prayer, meditation, and contemplative prayer. They have in common the recollection of the heart" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2721).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Teaching world civilization with joy and enthusiasm by Benjamin Lee Wren 2004 ISBN 0-7618-2747-1 page 236

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 The Way of Perfection by Teresa of Avila 2007 ISBN 1-4209-2847-3 page 145

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 The Byzantine Empire by Robert Browning 1992 ISBN 0-8132-0754-1 page 238

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 The last centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453 by Donald MacGillivray Nicol 2008 ISBN 0-521-43991-4 page 211

- ↑ Introducing Early Christianity by Laurie Guy 2011 ISBN 0-8308-3942-9 page 203

- ↑ Reading to live: the evolving practice of Lectio divina by Raymond Studzinski 2010 ISBN 0-87907-231-8 pages 26-35

- ↑ Vatican website: Benedict XVI, General Audience 2 May 2007

- ↑ The Fathers of the church: from Clement of Rome to Augustine of Hippo by Pope Benedict XVI 2009 ISBN 0-8028-6459-7 page 100

- ↑ Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5 page 88-94

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Globalization of Hesychasm and the Jesus Prayer: Contesting Contemplation by Christopher D. L. Johnson 2010 ISBN 978-1-4411-2547-7 pages 31-38

- ↑ Reading with God: Lectio Divina by David Foster 2006 ISBN 0-8264-6084-4 page 44

- ↑ After Augustine: the meditative reader and the text by Brian Stock 2001 ISBN 0-8122-3602-5 page 105

- ↑ Christian Spirituality: A Historical Sketch by George Lane 2005 ISBN 0-8294-2081-9 page 20

- ↑ Holy Conversation: Spirituality for Worship by Jonathan Linman 2010 ISBN 0-8006-2130-1 pages 32-37

- ↑ Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5 pages 91-92

- ↑ The Holy Spirit by F. LeRon Shults, Andrea Hollingsworth 2008 ISBN 0-8028-2464-1 page 103

- ↑ Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Keith J. Egan 1996 ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5 pages 38-39

- ↑ An Anthology of Christian mysticism by Harvey D. Egan 1991 ISBN 0-8146-6012-6 pages 207-208

- ↑ Orthodox Church: Its Past and Its Role in the World Today by John Meyendorff 1981 ISBN 0-913836-81-8 page

- ↑ The church in Italy in the fifteenth century by Denys Hay 2002 ISBN 0-521-52191-2 page 76

- ↑ Christian spirituality in the Catholic tradition by Jordan Aumann 1985 Ignatius Press ISBN 0-89870-068-X page 180

- ↑ Catholic encyclopedia

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Orthodox prayer life: the interior way by Mattá al-Miskīn 2003 ISBN 0-88141-250-3 St Vladimir Press, "Chapter 2: Degrees of Prayer" pages 39-42 [1]

- ↑ The art of prayer: an Orthodox anthology by Igumen Chariton 1997 ISBN 0-571-19165-7 pages 63-65

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Examining Religions: Christianity Foundation Edition by Anne Geldart 1999 ISBN 0-435-30324-4 page 108

- ↑ Christian Meditation for Beginners by Thomas Zanzig, Marilyn Kielbasa 2000, ISBN 0-88489-361-8 page 7

- ↑ An introduction to Christian spirituality by F. Antonisamy, 2000 ISBN 81-7109-429-5 pages 76-77

- ↑ Reading to live: the evolving practice of Lectio divina by Raymond Studzinski 2010 ISBN 0-87907-231-8 pages 188-195

- ↑ Christian Spirituality: An Introduction by Alister E. McGrath 1995 ISBN 0-631-21281-7 page 16

- ↑ The last centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453 by Donald MacGillivray Nicol 2008 ISBN 0-521-43991-4 page 211

- ↑ Christian Meditation by Edmund P. Clowney, 1979 ISBN 1-57383-227-8 pages 12-13

- ↑ The encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 3 by Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley 2003 ISBN 90-04-12654-6 page 488

- ↑ Mattá al-Miskīn, Orthodox Prayer Life: The Interior Way (St Vladimir's Seminary Press 2003 ISBN 0-88141-250-3), p. 56

- ↑ Meditation and Contemplation

- ↑ "Meditation is a prayerful quest engaging thought, imagination, emotion, and desire. Its goal is to make our own in faith the subject considered, by confronting it with the reality of our own life"(Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2723).

- ↑ "Contemplative prayer is the simple expression of the mystery of prayer. It is a gaze of faith fixed on Jesus, an attentiveness to the Word of God, a silent love. It achieves real union with the prayer of Christ to the extent that it makes us share in his mystery" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2724).

External links

Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "Prayer". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "Prayer". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

KSF

KSF