Zahhak

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

Zahhāk or Zahāk[1] (pronounced [zæhɒːk][2]) (Persian: ضحّاک) is an evil figure in Persian mythology, evident in ancient Persian folklore as Azhi Dahāka (Persian: اژی دهاک), the name by which he also appears in the texts of the Avesta.[3] In Middle Persian he is called Dahāg (Persian: دهاگ) or Bēvar Asp (Persian: بیور اسپ) the latter meaning "he who has 10,000 horses".[4][5] In Zoroastrianism, Zahhak (going under the name Aži Dahāka) is considered the son of Angra Mainyu, the foe of Ahura Mazda.[6] In the Shāhnāmah of Ferdowsi, Zahhāk is the son of a ruler named Merdās.

Etymology and derived words

Aži (nominative ažiš) is the Avestan word for "serpent" or "dragon."[7] It is cognate to the Vedic Sanskrit word ahi, "snake," and without a sinister implication.

The original meaning of dahāka is uncertain. Among the meanings suggested are "stinging" (source uncertain), "burning" (cf. Sanskrit dahana), "man" or "manlike" (cf. Khotanese daha), "huge" or "foreign" (cf. the Dahae people and the Vedic dasas). In Persian mythology, Dahāka is treated as a proper noun, and is the source of the Ḍaḥḥāk (Zahhāk) of the Shāhnāme.

The Avestan term Aži Dahāka and the Middle Persian azdahāg are the source of the Middle Persian Manichaean demon of greed Az,[8] Old Armenian mythological figure Aždahak, modern Persian aždehâ / aždahâ and Tajik Persian azhdahâ and Urdu Azhdahā (اژدها) as well as the Kurdish ejdîha (ئەژدیها) which usually mean "dragon".

Despite the negative aspect of Aži Dahāka in mythology, dragons have been used on some banners of war throughout the history of Iranian peoples.

The Azhdarchid group of pterosaurs are named from a Persian word for "dragon" that ultimately comes from Aži Dahāka.

Aži Dahāka (Dahāg) in Zoroastrian literature

Aži Dahāka is the most significant and long-lasting of the ažis of the Avesta, the earliest religious texts of Zoroastrianism. He is described as a monster with three mouths, six eyes, and three heads, cunning, strong, and demonic. In other respects Aži Dahāka has human qualities, and is never a mere animal.[citation needed]

Aži Dahāka appears in several of the Avestan myths and is mentioned parenthetically in many more places in Zoroastrian literature.[citation needed]

In a post-Avestan Zoroastrian text, the Dēnkard, Aži Dahāka is possessed of all possible sins and evil counsels, the opposite of the good king Jam (or Jamshid). The name Dahāg (Dahāka) is punningly interpreted as meaning "having ten (dah) sins".[citation needed] His mother is Wadag (or Ōdag), herself described as a great sinner, who committed incest with her son.[citation needed]

In the Avesta, Aži Dahāka is said to have lived in the inaccessible fortress of Kuuirinta in the land of Baβri, where he worshipped the yazatas Arədvī Sūrā (Anāhitā), divinity of the rivers, and Vayu, divinity of the storm-wind. Based on the similarity between Baβri and Old Persian Bābiru (Babylon), later Zoroastrians localized Aži Dahāka in Mesopotamia, though the identification is open to doubt. Aži Dahāka asked these two yazatas for power to depopulate the world. Being representatives of the Good, they refused.

In one Avestan text, Aži Dahāka has a brother named Spitiyura. Together they attack the hero Yima (Jamshid)[clarification needed] and cut him in half with a saw, but are then beaten back by the yazata Ātar, the divine spirit of fire.[citation needed]

According to the post-Avestan texts, following the death of Jam ī Xšēd (Jamshid),[clarification needed] Dahāg gained kingly rule. Another late Zoroastrian text, the Mēnog ī xrad, says this was ultimately good, because if Dahāg had not become king, the rule would have been taken by the immortal demon Xešm (Aēšma), and so evil would have ruled upon earth until the end of the world.

Dahāg is said to have ruled for a thousand years, starting from 100 years after Jam lost his Khvarenah, his royal glory (see Jamshid). He is described as a sorcerer who ruled with the aid of demons, the daevas (divs).

The Avesta identifies the person who finally disposed of Aži Dahāka as Θraētaona son of Aθβiya, in Middle Persian called Frēdōn. The Avesta has little to say about the nature of Θraētaona's defeat of Aži Dahāka, other than that it enabled him to liberate Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci, the two most beautiful women in the world. Later sources, especially the Dēnkard, provide more detail. Feyredon is said to have been endowed with the divine radiance of kings (Khvarenah, New Persian farr) for life, and was able to defeat Dahāg, striking him with a mace. However, when he did so, vermin (snakes, insects and the like) emerged from the wounds, and the god Ormazd told him not to kill Dahāg, lest the world become infested with these creatures. Instead, Frēdōn chained Dahāg up and imprisoned him on the mythical Mt. Damāvand[citation needed] (later identified with Damāvand).

The Middle Persian sources also prophesy that at the end of the world, Dahāg will at last burst his bonds and ravage the world, consuming one in three humans and livestock. Kirsāsp, the ancient hero who had killed the Az ī Srūwar, returns to life to kill Dahāg.[citation needed]

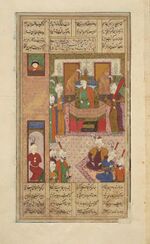

Zahhāk in the Shāhnāma

In Ferdowsi's epic poem, the Shāhnāmah, written c. 1000 AD and part of Iranian folklore the legend is retold with the main character given the name of Zahhāk and changed from a supernatural monster into an evil human being.

Zahhāk in Arabia

According to Ferdowsi, Zahhāk was born as the son of a ruler named Merdās (Persian: مرداس). Because of his lineage, he is sometimes called Zahhāk-e Tāzī (Persian: ضحاکِ تازی), meaning "Zahhāk the Tayyi". He was handsome and clever, but had no stability of character and was easily influenced by evil counsellors. Ahriman therefore chose him as the tool for his plans for world domination.

When Zahhāk was a young man, Ahriman first appeared to him as a glib, flattering companion, and by degrees convinced him that he ought to kill his own father and take over his territories. He taught him to dig a deep pit covered over with leaves in a place where Merdās was accustomed to walk; Merdās fell in and was killed. Zahhāk thus became both parricide and king at the same time.

Ahriman now took another guise, and presented himself to Zahhāk as a marvellous cook. After he had presented Zahhāk with many days of sumptuous feasts (introducing meat to the formerly vegetarian human cuisine), Zahhāk was willing to give Ahriman whatever he wanted. Ahriman merely asked to kiss Zahhāk on his two shoulders. Zahhāk permitted this; but when Ahriman had touched his lips to Zahhāk's shoulders, he immediately vanished. At once, two black snakes grew out of Zahhāk's shoulders. They could not be surgically removed, for as soon as one snake-head had been cut off, another took its place.

Ahriman now appeared to Zahhāk in the form of a skilled physician. He counselled Zahhāk that the only remedy was to let the snakes remain on his shoulders, and sate their hunger by supplying them with human brains for food every day, otherwise the snakes will feed on his own.

Zahhāk the Emperor

About this time, Jamshid, who was then the ruler of the world, through his arrogance lost his divine right to rule. Zahhāk presented himself as a savior to those discontented Iranians who wanted a new ruler. Collecting a great army, he marched against Jamshid, who fled when he saw that he could not resist Zahhāk. Zahhāk hunted Jamshid for many years, and at last caught him and subjected him to a miserable death—he had Jamshid sawn in half. Zahhāk now became the ruler of the entire world. Among his slaves were two of Jamshid's daughters, Arnavāz and Shahrnāz (the Avestan Arənavāci and Savaŋhavāci).

Zahhāk's two snake heads still craved human brains for food, so every day Zahhāk's spies would seize two men, and execute them so their brains could feed the snakes. Two men, called Armayel and Garmayel, wanted to find a way to rescue people from being killed from the snakes. So they learned cookery and after mastering how to cook great meals, they went to Zahhāk's palace and managed to become the chefs of the palace. Every day, they saved one of the two men and put the brain of a sheep instead of his into the food, but they could not save the lives of both men. Those who were saved were told to flee to the mountains and to faraway plains.

Zahhāk's tyranny over the world lasted for centuries. But one day Zahhāk had a terrible dream – he thought that three warriors were attacking him, and that the youngest knocked him down with his mace, tied him up, and dragged him off toward a tall mountain. When Zahhāk woke he was in a panic. Following the counsel of Arnavāz, he summoned wise men and dream-readers to explain his dream. They were reluctant to say anything, but one finally said that it was a vision of the end of Zahhāk's reign, that rebels would arise and dispossess Zahhāk of his throne. He even named the man who would take Zahhāk's place: Fereydun.

Zahhāk now became obsessed with finding this "Fereydun" and destroying him, though he did not know where he lived or who his family was. His spies went everywhere looking for Fereydun, and finally heard that he was but a boy, being nourished on the milk of the marvelous cow Barmāyeh. The spies traced Barmāyeh to the highland meadows where it grazed, but Fereydun had already fled before them. They killed the cow, but had to return to Zahhāk with their mission unfulfilled.

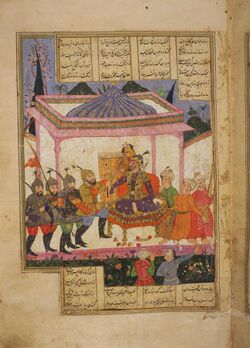

Revolution against Zahhāk

Zahhāk now tried to consolidate his rule by coercing an assembly of the leading men of the kingdom into signing a document testifying to Zahhāk's righteousness, so that no one could have any excuse for rebellion. One man spoke out against this charade, a blacksmith named Kāva (Kaveh). Before the whole assembly, Kāva told how Zahhāk's minions had murdered seventeen of his eighteen sons so that Zahhāk might feed his snakes' lust for human brains – the last son had been imprisoned, but still lived.

In front of the assembly Zahhāk had to pretend to be merciful, and so released Kāva's son. But when he tried to get Kāva to sign the document attesting to Zahhāk's justice, Kāva tore up the document, left the court, and raised his blacksmith's apron as a standard of rebellion – the Kāviyāni Banner, derafsh-e Kāviyānī (درفش کاویانی). He proclaimed himself in support of Fereydun as ruler.

Soon many people followed Kāva to the Alborz mountains, where Fereydun was now living. He was now a young man and agreed to lead the people against Zahhāk. He had a mace made for him with a head like that of an ox, and with his brothers and followers, went forth to fight against Zahhāk. Zahhāk had already left his capital, and it fell to Fereydun with small resistance. Fereydun freed all of Zahhāk's prisoners, including Arnavāz and Shahrnāz.

Kondrow, Zahhāk's treasurer, pretended to submit to Fereydun, but when he had a chance he escaped to Zahhāk and told him what had happened. Zahhāk at first dismissed the matter, but when he heard that Fereydun had seated Jamshid's daughters on thrones beside him like his queens, he was incensed and immediately hastened back to his city to attack Fereydun.

When he got there, Zahhāk found his capital held strongly against him, and his army was in peril from the defense of the city. Seeing that he could not reduce the city, he snuck into his own palace as a spy, and attempted to assassinate Arnavāz and Shahrnāz. Fereydun struck Zahhāk down with his ox-headed mace, but did not kill him; on the advice of an angel, he bound Zahhāk and imprisoned him in a cave underneath Mount Damāvand, binding him with a lion's pelt tied to great nails fixed into the walls of the cavern, where he will remain until the end of the world. Thus, after a thousand years' tyranny, ended the reign of Zahhāk.

Place names

"Zahhak Castle" is the name of an ancient ruin in Hashtrud, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran which according to various experts, was inhabited from the second millennia BC until the Timurid-era. First excavated in the 19th century by British archeologists, Iran's Cultural Heritage Organization has been studying the structure in 6 phases.[9]

In popular culture

- The Konami video game Suikoden V has two references to Zahhak—an evil knight named "Zahhak" as well as a large ship named "Dahak".

- In Starcraft II: Heart of the Swarm, there exists a primal zerg that goes by a similar name (Dehaka).

- In the webcomic Homestuck of MS Paint Adventures, Equius Zahhak is a troll with extreme physical strength and a fascination with horses.

- In the visual novel Sekien no Inganock - What a Beautiful People, incorrectly-manifested Kikai are referred to as "Zahhak".

- In the video game series Mass Effect, a Quarian named Professor Zahak was involved in the creation of the Geth, a hive mind consciousness of artificially intelligent machines.

- In the Xenaverse, Zahhak (referred to as Dahak) is the supernatural (and thoroughly Satanic) adversary whom both Xena and later Hercules on Hercules: The Legendary Journeys must defeat in order to save the world from utter destruction. When Dahak appears on Hercules, his appearance is like a crustacean.

- In Final Fantasy Legend III (known outside the United States as SaGa 3), intermediate boss Dahak is depicted as a multiple-headed lizard.

- In Prince of Persia the Prince of Persia flees from a powerful shadowy figure called The Dahaka.

- In Future Card Buddyfight the buddy of the main antagonist is named Demonic Demise Dragon, Azi Dahaka.

- The Marvel MAX Terror Inc. issues feature an immortal villain named Zahhak, bound to two demonic snakes. Unless fed with other people's brains, they start eating his own.

- In Quest Corporation video game Ogre Battle 64, Ahzi Dahaka is a venerable dragon of the Earth element that is commonly encountered during the latter half of the game.

- In High School DxD, Azi Dahaka is an Evil Dragon and considered as a very strong being. He leads a terrorist group together with another Evil Dragon named Apophis.

- In the light novel series, Problem Children Are Coming from Another World, Aren't They?, Azi Dahaka is represented as a three-headed white dragon and is one of the main antagonists in the series.

- In "In the land of Angra Mainyu" by Stephen Goldin, Nameless Places, Arkham House,1975, Zahhak has escaped his cell and the professional hero must re-confine him until Judgement Day.

- In The Darkness (comics) and videogame of the same name, the protagonist Jackie Estacado could be a faint reference to Zahhak. He is possessed by an evil force (the titular "The Darkness") which, among other things, causes dark snakes to grow out of his shoulders which seem to like eating humans.

- In the Mount and Blade Warband mod Prophesy of Pendor, Azi Dahaka is the evil snake goddess worshiped by the Snake Cult. They have infiltrated the Empire faction and represent an important antagonist in the game.

- In Project Celeste, a fan remake of Age of Empires Online, there is a legendary piece of gear called Zahhak's Sword of the Undying.[10]

- In Shadowverse card game Azi Dahaka appear as a legendary Dragoncraft-class card come from Chronogenesis Expansion.

- In Mage: The Awakening, Dahhak is portrayed as a fallen king of Atlantis, as well as the Aeon of Pandemonium.

- In the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game, Dahak is the god of chromatic dragons, and the son of the dragons Apsu and Tiamat. He seeks to kill his father and reign over all dragonkind.

Other dragons in Iranian tradition

Besides Aži Dahāka, several other dragons and dragon-like creatures are mentioned in Zoroastrian scripture:

- Aži Sruvara - the 'horned dragon'

- Aži Zairita - the 'yellow dragon,' that is killed by the hero Kərəsāspa, Middle Persian Kirsāsp.[11] (Yasna 9.1, 9.30; Yasht 19.19)

- Aži Raoiδita - the 'red dragon' conceived by Angra Mainyu's to bring about the 'daeva-induced winter' that is the reaction to Ahura Mazda's creation of the Airyanem Vaejah.[12] (Vendidad 1.2)

- Aži Višāpa - the 'dragon of poisonous slaver' that consumes offerings to Aban if they are made between sunset and sunrise (Nirangistan 48).

- Gandarəβa - the 'yellow-heeled' monster of the sea 'Vourukasha' that can swallow twelve provinces at once. On emerging to destroy the entire creation of Asha, it too is slain by the hero Kərəsāspa. (Yasht 5.38, 15.28, 19.41)

The Aži / Ahi in Indo-Iranian tradition

Stories of monstrous serpents who are killed or imprisoned by heroes or divine beings may date back to prehistory, and are found in the myths of many Indo-European peoples, including those of the Indo-Iranians, that is, the common ancestors of both the Iranians and Vedic Indians.

The most obvious point of comparison is that in Vedic Sanskrit ahi is a cognate of Avestan aži. However, In Vedic tradition, the only dragon of importance is Vrtra, but "there is no Iranian tradition of a dragon such as Indian Vrtra" (Boyce, 1975:91-92) Moreover, while Iranian tradition has numerous dragons, all of which are malevolent, Vedic tradition has only one other dragon besides Vṛtra - ahi budhnya, the benevolent 'dragon of the deep.' In the Vedas, gods battle dragons, but in Iranian tradition, this is a function of mortal heroes.

Thus, although it seems clear that dragon-slaying heroes (and gods in the case of the Vedas) "were a part of Indo-Iranian tradition and folklore, it is also apparent that Iran and India developed distinct myths early." (Skjaervø, 1989:192)

See also

- List of dragons in mythology and folklore

- False messiah

- Arnavāz

- Azhdahak (Armenian mythical being), identified as Astyages

References

- ↑ "zahāk or wolflike serpent in the Persian and kurish Mythology | khosro gholizadeh". Academia.edu. 1970-01-01. https://www.academia.edu/2916523/zahak_or_wolflike_serpent_in_the_Persian_Mythology_. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ↑ loghatnaameh.com. "ضحاک بیوراسب | پارسی ویکی". Loghatnaameh.org. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. https://web.archive.org/web/20140201182300/http://www.loghatnaameh.org/dehkhodaworddetail-cd5088b4eaa749f8a25507f1a63b9fc7-fa.html. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ↑ Bane, Theresa (2012). Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures. McFarland. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-7864-8894-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=njDRfG6YVb8C&pg=PA335. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ کجا بیوراسپش همی خواندند / چُنین نام بر پهلوی راندند

کجا بیور از پهلوانی شمار / بود بر زبان دری دههزار - ↑ "Characters of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh". heritageinstitute.com. http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/shahnameh/characters.htm. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ↑ "Persia: iv. Myths an Legends". Encyclopaedia Iranica. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-iv-myths-and-legends. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ↑ For Azi Dahaka as dragon see: Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0

- ↑ Appears numerous time in, for example: D. N. MacKenzie, Mani’s Šābuhragān, pt. 1 (text and translation), BSOAS 42/3, 1979, pp. 500-34, pt. 2 (glossary and plates), BSOAS 43/2, 1980, pp. 288-310.

- ↑ (in fa). Cultural Heritage News Agency. 2007-03-04. Archived from the original on 2006-10-01. https://web.archive.org/web/20061001142816/http://www.chn.ir/news/?section=2&id=31507. Retrieved 2006-05-28.

- ↑ https://forums.projectceleste.com/threads/zahhaks-sword-of-the-undying.3821/

- ↑ Zamyād Yasht, Yasht 19 of the Younger Avesta (Yasht 19.19). Translated by Helmut Humbach, Pallan Ichaporia. Wiesbaden. 1998.

- ↑ The Zend-Avesta, The Vendidad. The Sacred Books of the East Series. 1. Translated by James Darmesteter. Greenwood Publish Group. 1972. ISBN 0837130700.

Bibliography

- Boyce, Mary (1975). History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. I. Leiden: Brill.

- Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0

- Skjærvø, P. O (1989). "Aždahā: in Old and Middle Iranian". Encyclopedia Iranica. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 191–199. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt1.

- Khaleghi-Motlagh, DJ (1989). "Aždahā: in Persian Literature". Encyclopedia Iranica. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 199–203. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt2.

- Omidsalar, M (1989). "Aždahā: in Iranian Folktales". Encyclopedia Iranica. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 203–204. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt3.

- Russell, J. R (1989). "Aždahā: Armenian Aždahak". Encyclopedia Iranica. 3. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 204–205. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/azdaha-dragon-various-kinds#pt4.

External links

- Discussion of Az at Encyclopedia Iranica

- A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Zahhak

| Preceded by Jamshid |

Legendary Kings of the Shāhnāma 800-1800 (after Keyumars) |

Succeeded by Fereydun |

KSF

KSF