Alchemy

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 10 min

| It matters Chemistry |

| Action and reaction |

| Elementary! |

| Spooky scary chemicals |

| Er, who's got the pox? |

| Style over substance Pseudoscience |

| Popular pseudosciences |

| Random examples |

Alchemy is the protoscience that was a precursor to modern chemistry.[1] It is a mix of religion, mysticism, and a few practical observations. With the rise of the scientific method, the relatively simplistic base of alchemy transmuted slowly into a gleaming nugget of pure chemistry.

Beliefs[edit]

It's quite hard to nail down what alchemists believed in general. For a start, they tended to disagree with each other as to the details of what they did. Their books were confused and misleading. On the one hand, they did not want anybody else to know the "secrets" that they had laboured so long to discover; on the other, they most likely didn't really know what they were talking about anyway (all the better reason to keep it a secret).

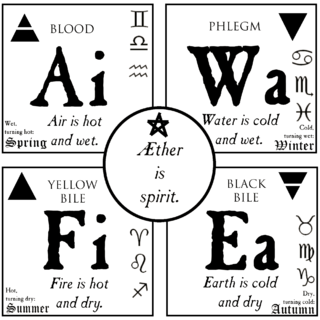

It is possible to glean a few generalities. All matter is based on four elements — earth, air, fire, water — and three essences — mercury, salt, sulphur. These don't bear any resemblance to what we understand by the terms, though. Water, for example, is at its purest in Heaven. In the sky, there is a form of water which is not as pure as in Heaven, but it's still better than the rubbish we've got here, which is only a poor imitation. This was true of all the elements and essences. Thus, any experiment using these substances on Earth was basically doomed to failure from the outset.

Metals were a real favourite of alchemists. There were seven — gold, silver, mercury, tin, copper, iron, and lead. Since any self-respecting piece of mystical pseudoscience can't be complete without astrology, the metals had their analogue in the (then-known) "planets" — the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn respectively.

The confusing nomenclature was one of the major problems with alchemy. Even modern chemists have trouble trying to work out what alchemists were trying to do. When an alchemist referred to "mercury", it was unclear (possibly deliberately) as to whether he was referring to the metal, the essence, or the planet. Since "mercury" was, in any case, the generic name for several mercury compounds as well as the liquid metal, it's hardly surprising that alchemists spent centuries chasing their tails and not doing anything useful.

Everybody knows that alchemists wanted to transmute metals, specifically turning base metals into gold. They saw metals as being in a hierarchy, with lead at the bottom and gold at the top. It was a trivial matter to turn metals into lead (so they claimed), so it was hardly worth going on about it. Gold was the goal. They believed that metals transmuted naturally inside the Earth. This belief was presumably reinforced by the observation that silver mines often had trace amounts of gold. The gold was there as part of the inevitable transformation of silver into gold, they thought. Bizarre as it might sound, it is barely different to people assuming that "black gold" grows underground, as per the abiotic oil theory.[note 1]

The alchemist tried to speed up this "natural" transmutation in the laboratory. Naturally, the philosopher's stone was the key to making this process work. Its appearance was well-known. It was not a stone, but a white powder. This powder, when mixed into the alchemical experiment, would cause the transmutation. Various people claimed to have found the philosopher's stone, but their claims were somewhat unreliable.

Evidence[edit]

“”Chemistry began by saying it would change the baser metals into gold. By not doing that it has done much greater things.

|

| —Ralph Waldo Emerson |

If you're scratching your head at the explanation of the "theory" of alchemy presented above, that could be due to a poor explanation. More likely is that the explanation is a pretty good representation and that alchemy just made no sense whatsoever — to modern minds, at least. In the past, there was a steady stream of men (always men) who made it their mission to waste their time on alchemy, despite the lack of success over hundreds of years.

The alchemists had a few party tricks. These, with their alchemical explanations, might help explain what the principles were and how they were applied. The following experiments show how they interpreted such results:

- Ordinary water is boiled in an open vessel; the water is changed to a vapour which disappears, and a white powdery earth remains in the vessel. Conclusion — water is changed into air and earth. In actual fact, water contains minerals which are left behind after boiling; boiling water may also react with the vessel.

- A piece of red-hot iron is placed in a bell-jar, filled with water, held over a basin containing water; the volume of the water decreases and the air in the bell-jar takes fire when a lighted taper is brought into it. Conclusion — Water is changed into fire. The modern understanding is that the iron decomposes water into oxygen and hydrogen, which burns when set on fire.

These experiments can be explained by modern chemistry. To the uninitiated, the modern explanations might seem as arcane and esoteric as the alchemical ones. The difference is that the modern explanations are consequences of well-understood rules which have predictive and consistent results when applied to other experiments. To the alchemist, these were isolated results and had no relation to any other phenomena. Worse still, it seems that they liked these experiments because they seemed to confirm their belief in the order of the world, thereby reinforcing their preconceived ideas.

Lawrence Principe, a professor of history of science and professor of chemistry at Johns Hopkins University has gone back to original alchemy treatises and tried to reproduce some of them.[2] His successes include:[2]

- Volatilizing gold by sublimation

- Recreating the "Bologna stone", which glows in the dark for a few minutes after being exposed to light

Eternal life[edit]

Their other main preoccupations were to find a "cure" for death or "elixir of life" and to find a universal cure for all diseases or "panacea". For those not lucky enough to have the elixir, they could try convoluted and unrealistic diets, such as the following suggested by Arnold de Villeneuve:[3]

the person intending so to prolong his life must rub himself well, two or three times a week, with the juice or marrow of cassia […] Every night, upon going to bed, he must put upon his heart a plaster, composed of a certain quantity of oriental saffron, red rose-leaves, sandal-wood, aloes, and amber, liquified in oil of roses and the best white wax. In the morning, he must take it off, and enclose it carefully in a leaden box till the next night, when it must be again applied. […] he shall take […] chickens, […U]pon these he is to feed, eating one a day; but previously the chickens are to be fattened by a peculiar method […]. Being deprived of all other nourishment till they are almost dying of hunger, they are to be fed upon broth made of serpents and vinegar, which broth is to be thickened with wheat and bran.

Although there is no evidence, it is reasonable to assume that at least a few people wasted their time and money on such absurd recipes in order to obtain eternal life.

The search for aqua vitae, however, did result in several forms of distilled beverages, under the assumption that they did, indeed, promote long life and cure diseases. Notably among these is Chartreuse,![]() which was invented by French Monks and contains distillates of over a hundred different herbs, most of which were understood during the 16th and 17th centuries to have healing capabilities. The line of reasoning from the monks appeared to be, "Well, instead of having lots of individual cures for known maladies and diseases, let's bottle them all together!" in what would be a precursor to the less-tasty but equally effective modern-day elixir known as "NyQuil".

which was invented by French Monks and contains distillates of over a hundred different herbs, most of which were understood during the 16th and 17th centuries to have healing capabilities. The line of reasoning from the monks appeared to be, "Well, instead of having lots of individual cures for known maladies and diseases, let's bottle them all together!" in what would be a precursor to the less-tasty but equally effective modern-day elixir known as "NyQuil".

Other alchemists soon followed suit — in fact, the word "whiskey" is derived from the phrase "water of life" in both Irish and Scottish Gaelic.

Successes[edit]

This all sounds rather bad for alchemy, but it did make a few discoveries that were — and are — worthwhile. True, it's not much to show for over 1000 years' worth of research, but it proves that alchemy wasn't a total waste of time.

The following are indisputably achievements of alchemists; the only argument is to which alchemist managed this and when:

- Basic chemical procedures, most notably distillation, including fractional distillation

- Discovery of phosphorus, antimony, and bismuth (although the proof of the elemental nature of these metals came later)

- Preparation of nitric, hydrochloric, and sulfuric acid

- Refinement of distillation practices; specifically the purification of alcohol spirits, which has countless medical applications (and some non-medical applications).

Notable alchemists[edit]

For the most part, alchemists fell into two groups:

- Obsessive loners who wasted a fortune chasing a shadow.

- Con men who needed "just a little more investment" to "further their research" into the philosopher's stone.

Needless to say, they were generally looked down upon and distrusted. Despite this, alchemy was a body of knowledge that many learned men at least dabbled in. Some of them were better known than others.

- Jabir ibn Hayyan.

A somewhat mythical figure in that nothing was written about him until over a century after his purported death, he is nonetheless known as "the father of modern chemistry" for his methodological approach to alchemy. Regardless, the works attributed to him were revolutionary for categorising substances based on their chemical properties, and the methods he supposedly used are regarded as an early form of the modern scientific method.

A somewhat mythical figure in that nothing was written about him until over a century after his purported death, he is nonetheless known as "the father of modern chemistry" for his methodological approach to alchemy. Regardless, the works attributed to him were revolutionary for categorising substances based on their chemical properties, and the methods he supposedly used are regarded as an early form of the modern scientific method. - Zakariya Razi

was a Persian polymath and noted skeptic at a time where questioning Islamic dogma could get you executed. He is widely considered to be one of history's most influential medical scholars, with his works having laid the foundation for modern medicine. He is also considered to be the father of distillation, having wrote extensively about the distillation of wine, calling the distillate "al'koh'l of wine", from which we get the word "alcohol".

was a Persian polymath and noted skeptic at a time where questioning Islamic dogma could get you executed. He is widely considered to be one of history's most influential medical scholars, with his works having laid the foundation for modern medicine. He is also considered to be the father of distillation, having wrote extensively about the distillation of wine, calling the distillate "al'koh'l of wine", from which we get the word "alcohol". - Isaac Newton was of course the most famous alchemist. He is most famous for his mathematical and optical achievements. His contribution to alchemy was minimal.

- Philippus von Hohenheim, a.k.a. Paracelsus, is better known as the forerunner to doctors than as an alchemist. His contribution was to replace one highly dangerous form of medicine with a slightly less dangerous form. Today, he would be dismissed as a quack for his nonsense.

- Nicolas Flamel

received a surge in fame recently by being featured in a Harry Potter book. According to some stories, he discovered the philosopher's stone, faked his death, and is still living now. According to others, he made a fortune as a debt collector for expelled Jewish bankers and made himself immortal by setting up schools and hospitals in his name.

received a surge in fame recently by being featured in a Harry Potter book. According to some stories, he discovered the philosopher's stone, faked his death, and is still living now. According to others, he made a fortune as a debt collector for expelled Jewish bankers and made himself immortal by setting up schools and hospitals in his name.

The end[edit]

Alchemy never really ended; it grew up, learned how it should behave properly and underwent a rebranding exercise by calling itself chemistry. The start of this transition came in the late 17th century, as with so many other areas of science. Robert Hooke hit on the brainwave of recording meticulously everything that occurred, even noting the weather and planetary positions. The latter was a response to the astrological element, since nobody had actually been checking whether it had an effect; they simply assumed it did.

It has to be said that chemistry is extremely complicated, and trying to find unifying features for all the seemingly random changes that occur is very difficult. The old principles of elements and essences gave way to the phlogiston theory in the early 18th century. This was a huge improvement because, although wrong, it simplified the theoretical framework to the extent that it was possible to make meaningful experiments to test the theory.

The phlogiston theory was finally blown apart by Anton Lavoisier in a series of painstakingly precise experiments. He performed the alchemists' party tricks described above and carefully weighed everything before and after the reaction. In this way, he proved that the weights remained the same and that he was controlling precisely what was reacting and how. Either Lavoisier was the best experimentalist ever, or he knew the answer before he started (probably both). Either way, alchemy was officially dead after his experiments and chemistry took off at an amazing pace. It was without Lavoisier, unfortunately — following an appointment with Mme Guillotine in 1794, he was unable to continue his research.

Today[edit]

The triumph of the scientific method over alchemy is one of the most impressive victories in the history of thought. There are a few mystics and throwbacks who try to keep the old ways going, but alchemy — in its original form — is basically dead.

Physicists have cracked the age-old alchemical dream of turning metals into gold. For example, to convert lead into gold, you just need a particle accelerator and huge energy input. You then bombard lead nuclei until you remove 3 protons from one, leaving a gold nucleus. The process is easier with bismuth — not the conversion, but the subsequent detection or extraction of the incredibly tiny quantity of gold produced: the scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who tried it could only detect the presence of gold from the decay signature of radioactive gold isotopes produced.[4]

Alchemical themes and the classical elements still appear in anime and other popular culture. Alchemy abides as part of the wonderlore of Western ceremonial magic, which continues to assign planets to the classical metals.

Crankery[edit]

Medieval-style alchemy is still practiced today,[5] but it is the realm of spiritualists and cranks such as the Rosicrucians. In France in the early and mid 20th century, the mysterious alchemist known as Fulcanelli![]() and his pupil Eugène Canseliet

and his pupil Eugène Canseliet![]() reached a considerable level of fame, thanks to skilful self-publicity. Fulcanelli carefully cultivated an air of mystery and his identity remains unknown. Under his guidance, Canseliet allegedly converted 100g lead into gold, although subsequent attempts to repeat the process all ended in failure. Canseliet also managed to link alchemy with the near-magical powers of modern science by claiming early knowledge of a potential atomic bomb in 1937 (if stories are to be believed). Fulcanelli apparently had links to reputable scientists including Jules Violle, who made pioneering measurements of mean solar electromagnetic radiation, as well as Jacques Bergier, a chemical engineer and Resistance hero who also wrote on the occult.[6][7]

reached a considerable level of fame, thanks to skilful self-publicity. Fulcanelli carefully cultivated an air of mystery and his identity remains unknown. Under his guidance, Canseliet allegedly converted 100g lead into gold, although subsequent attempts to repeat the process all ended in failure. Canseliet also managed to link alchemy with the near-magical powers of modern science by claiming early knowledge of a potential atomic bomb in 1937 (if stories are to be believed). Fulcanelli apparently had links to reputable scientists including Jules Violle, who made pioneering measurements of mean solar electromagnetic radiation, as well as Jacques Bergier, a chemical engineer and Resistance hero who also wrote on the occult.[6][7]

In addition to shilling glorified bleach, "Archbishop" Jim Humble once claimed he found a way to transmute radiation to precious metals like gold and platinum, which was evidently so easy that even a high schooler could do it, and he'd sell it to you for a mere $20 (quite a steal given it was $99)[8] in a book titled Zero Fusion and Atomic Alchemy: How to reduce radiation to zero and make GOLD in the process. Similar to those adhering to the free energy suppression conspiracy theory, Humble claimed this process was supposedly being kept under wraps by "thousands of people receiving their corruption payoff".[9]

This, of course, makes absolutely zero sense. Given the amount of money, time, and resources spent on protecting people from radiation and researching ways to deal with nuclear waste and the fact that concerns about waste and radiation leaks are one of the most common arguments against nuclear power, one would think the nuclear industry would be tripping over themselves to implement Humble's techniques, but, no, some Vast Conspiracy, which Humble, naturally, has no proof of, evidently finds it more profitable to keep this stuff under wraps even though they wouldn't actually benefit much from doing so.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Much of this article is sourced from The Story of Alchemy and the Beginnings of Chemistry by M. M. Pattison Muir (available from Project Gutenberg)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 This chemist is unlocking the secrets of alchemy by Ben Guarino (January 30, 2018) The Washington Post.

- ↑ Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Charles Mackay (available from Project Gutenberg)

- ↑ Fact or Fiction?: Lead Can Be Turned into Gold, Scientific American, Jan 31, 2014

- ↑ http://www.levity.com/alchemy/

- ↑ Who Was Fulcanelli?, Historic Mysteries

- ↑ The first rule of alchemy: you do not talk about alchemy, Vanesa Martinez, TU Dublin, RTE, 3 May 2018

- ↑ Zero Fusion and Atomic Alchemy. Archived December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Zero Fusion and Atomic Alchemy. Archived July 15, 2015.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Hilariously, there is a grain of merit to the stereotypical alchemical goal of transmuting lead into gold, as it has been discovered that the difference between a gold atom and a lead atom is just three protons. However, it has not been discovered how to rip protons off of a lead atom to turn it into a good atom (or how to do this to enough atoms to make this worthwhile), and the science of atom manipulation generally has better things to be doing. (More on that later.)

KSF

KSF