Communism

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 33 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 33 min

| Join the party! Communism |

| Opiates for the masses |

| From each |

| To each |

“”From each according to their ability, to each according to their needs.

|

| —Slogan popularised by Karl Marx.[1] |

Communism is a far-left ideology whose adherents[2] believe that society would be better if it was structured around common ownership of the means of production and the abolition of social classes, money, and the state.[3]

Communism's most familiar form(s) are informed by Marxist theory, which posits that history moves through stages driven by class conflict. This analysis maintains that feudalism, led by aristocrats, was transformed into capitalism through class conflict with the bourgeoisie (those who own the means of production, typically upper middle class and above). Class conflict between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat (working class) will lead to the transition from a capitalist to a socialist society. This is regarded as the point where the proletariat takes the means of production from the bourgeoisie, effectively ending all class distinctions as society transitions into communism.[4]

Modern communist thought took shape in 19th-century Europe, when appalling working conditions and low wages were the norm and brought Europe to the brink of large-scale revolution.[5] These worsening social tensions made the new theory in town, communism, a serious challenge to the status quo and gained it a broad popular support base. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels predicted that capitalism would simply become more and more oppressive in response to communism and eventually result in revolution, but this linear process did not happen...

Rather, during the 20th century, the arrival of more progressive and/or left-leaning governments and the development of a social safety net helped to diminish economic inequality in much of the developed world, which undermined much of communist dogma. Additionally, various regimes claiming to be communist devolved into totalitarian, atrocity-ridden dictatorships. These dictatorships often left mass graves. Towards the end of the century, most of the Soviet-aligned communist regimes fell due to a combination of Cold War pressures, popular protests and strikes, economic problems, and Mikhail Gorbachev's liberalization policies.[6] Meanwhile, many former followers of Marx and Engels, such as Eduard Bernstein,![]() abandoned communism and turned to social democratic and reformist socialist politics.

abandoned communism and turned to social democratic and reformist socialist politics.

Communism, at least in the Bolshevist form as well as any offshoots thereof, is largely discredited, and few nations even claim to still adhere to it.[7] Almost all that do have introduced market reforms to liberalize their economies to varying extents.[8][9][10] However, said modern communist countries are still nearly always hardline authoritarian with blatant indifference to human rights and utter impoverishment. While, indeed, there are non-atrocious forms of communism, they are an exceedingly rare occurrence, with most former communists turning to social democracy in the same way followers of Marx and Engels did. However, with the advent of neoliberalism and the rising wealth gap, some communist ideas are seeing somewhat of a resurgence, although the term "communism" has been poisoned by authoritarian regimes. In general, the forms more popular today, at least in the West, include reformist socialist ideas like democratic socialism and market socialism, as well as libertarian socialism, and anarchism, each of which tries to address or distance themselves from the pitfalls that led the communist regimes of the past to become totalitarian nightmares.

Communism in theory[edit]

Early forms[edit]

Communism, as a political philosophy advocating the communal ownership of property and abolition of commodity production, has been around almost since the dawn of politics. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that early hunter-gatherer societies represented primitive communism. Such societies had no social classes or forms of capital.[11] Many religious groups and other utopian communities throughout history have practiced it on a small scale as well — examples include early Christians (with the very first Christians being no exception — see Acts 2:44 onward) and the Pythagoreans.[12] The French revolutionary Gracchus Babeuf has been called "the first revolutionary communist" and was killed for conspiring against the First French Republic during the French Revolution.[13] These early forms of communism might be referred to as "proto-communism".![]()

Marxism[edit]

The most (in)famous form of communism is derived from the ideas of Karl Marx. Marx, who had studied the German idealist Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, attempted to turn Hegel's idealism on its head in his own philosophy. He also sought to remove the idealism from earlier communist ideas and give them a materialistic footing (what later came to be called "dialectical materialism").

Marx is quoted as saying that "if anything is certain, it is that I myself am not a Marxist", referring to the misunderstanding or misapplication of his ideas.[14] However, a set of core beliefs called "Marxist" can certainly be ascribed to Marx, most notably the overthrow of capitalism, rejection of reformism, emphasis on the importance of socio-economic factors and class conflict in history, and the rejection of religious or semi-religious justifications for the existing order.[15] Marxism can also be differentiated from other branches of socialism by its insistence on "scientific socialism".[16] Marx believed contemporary socialists making arguments based on morality and justice (the sort attacked by Engels in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific) were missing the point entirely. He would reportedly burst out laughing when anyone tried to talk to him about morality. For Marx, the capitalist system's contradictions made the emergence of socialism (and thus eventually communism) inevitable. He saw himself as a scientist analyzing the development of political economy, not a moralist agitating for its abolition.

Marx initially rejected the reformist tactics and goals of social democrats in his Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League in 1850.[17] Specifically, he argued that measures designed to increase wages, improve working conditions, and provide welfare payments would be used to dissuade the working class away from socialism and the revolutionary consciousness he believed was necessary to achieve a socialist economy. Reform and welfare schemes would thus threaten genuine structural changes to society by making the conditions of workers in capitalism more tolerable. Marx's view on labor reform matured as his thought developed, and he later expressed disagreement with French workers' leaders Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue on this point,[18] accusing them of 'revolutionary phrase-mongering' and denying the value of reformist struggles.[note 1]

The Marxist view of society focuses on economic and class relationships and the role of the workers, or the proletariat. Marx theorized that human society develops from primitive communism to a slave society, then to feudalism, and after feudalism ceases to be productive, to capitalism. He claimed that capitalism, in a similar manner, leads to socialism since once it is developed enough, the proletariat will be an organized force capable of revolution: "What the bourgeoisie, therefore, produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers."

When a workers' revolution has brought about the "dictatorship of the proletariat,"[note 2] the state would "wither away" and produce communism, a classless and stateless form of social organization. Despite appearances, Marx was not deterministic. He did not believe the revolution would just happen automatically, but rather that socialists would have to actively help educate the workers and fight for it. However, crises and such would aid it. The Communist Manifesto[19] was his statement of purpose, though he later called parts of it (especially the ten generally applicable points for "advanced societies") antiquated. It was mainly a propagandistic document and thus did not go into the details of economic theory, as does his later work, Das Kapital.[20] However, one thing that Marx explicitly warned about was that attempts to do this in a society that had not yet undergone an Industrial Revolution would most likely backfire, which brings us to...

Leninism[edit]

“”Dictatorship is rule based directly upon force and unrestricted by any laws. The proletariat's revolutionary dictatorship is rule won and maintained by the use of violence by the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, rule that is unrestricted by any laws.

|

| —Vladimir Lenin, The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky (1918).[22] |

Vladimir Lenin, leading the Russian Revolution, paid large amounts of lip service to Marx while in reality taking more ideas from Blanquism (even though Marx hadn't thought too highly of the chances of revolution from a feudalistic society and had coined the term 'dictatorship of the proletariat' to differentiate from the Blanquist minority dictatorship) and declaring open class warfare on the bourgeoisie (and that he would bring "Peace, Bread, and Land!") in an attempt to take power. Lenin jumped the gun by leading a communist revolution with a small group of intellectuals and without waiting for a significant working class to develop, trying to jumpstart a socialist state by "skipping" an entire step in the process Marx had described. In Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism,[23] Lenin argued that foreign capital intervention in backward countries (colonies and economic dependents) created the conditions for socialist revolution, which was contrary to Menshevik thought (that the Revolution in Russia should first impose capitalism as a way for socialism to develop).[24] Lenin was basically asking: "Why would you need to make a revolution to create a capitalist system when capitalism is already here?" Although a mostly peasant and backward country, Russia had developed a significant working class in the cities. Lenin saw this as the basis for the revolution in which workers and peasants would unite against the monarchy and the bourgeoisie.

Leninism, as this would become known, is a sort of forced Marxism on steroids, in which a small yet significant group of leaders, known as a vanguard, ensured "two revolutions for the price of one" by "telescoping" the capitalist and communist revolutions and took over the state and industry. In Leninism, the revolutionary party would lead the revolution. This party would be "the voluntary selection of the most advanced, more aware, more selfless and more active workers." It would handle the socialist state and transform society into "communism" (as the beginning of the idea of socialism and communism being different stages of revolution originated mainly from Lenin). Crucially, this idea of a vanguard party was a significant criticism of left-wing socialists to the "mass" party structure of most socialist organizations, which had become a massive bureaucratic apparatus, with thousands of leased politicians and union officials who exercised absolute control of the press and labor organizations that adhered to socialism. A soviet state was established, and opposition on both right and left fomented and soon exploded into the brutal Russian Civil War, which, mainly due to the harsh conditions faced by Lenin and his supporters (German invasion and civil war), resulted in the elevation of the Bolsheviks to become a new elite within Russia. Simultaneously, the workers and peasants —the same people the Bolsheviks claimed to represent— were subjected to the same dictatorial control as in the Tsar's regime.

There was a total of one democratic election in Russia after the October Revolution. When the Bolsheviks lost to the moderate and liberal parties (the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks), they sent in the Red Guard and closed the Constituent Assembly.[25] It is true that Lenin's ideas (especially applying planned economy principles to agriculture) didn't really work, but though some reforms were suggested, Lenin and Trotsky killed most of those presenting them. Then Lenin died.

Stalinism vs. Trotskyism[edit]

“”Stalin is a Genghis Khan, an unscrupulous intriguer, who sacrifices everything else to the preservation of power... He changes his theories according to whom he needs to get rid of next.

|

| —Nikolai Bukharin, 1928.[26] |

The popular appeal of the revolutionary wave begun by the Russian Revolution understandably fell short in nations sporting a social democratic option. In Hungary, the government persecuted the communist leaders. In Italy, the communists didn't seize power; instead, they managed to indirectly pave the way for Benito Mussolini (who started out as a far-leftist).[27] In Germany, the powers-that-be outright murdered the revolutionaries Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht[28] (aided by the Freikorps, which would later become the basis of the Nazi party). Additionally, the Soviet Union's first experiment in spreading communism by force, the 1919 Polish-Soviet War, ended in embarrassing failure.[29]

All of these factors indicated that the Russian Revolution was becoming more isolated. Meanwhile, the notorious thug and military leader Joseph Stalin used his personal fame to gather supporters inside the Soviet Union's Party bureaucracy, eventually becoming General Secretary.[30] As General Secretary, Stalin ensured that he was one of the only people allowed to see Lenin after his stroke, and he used that position to ensure that he became the country's new leader.

Stalin felt that the failure of just about all communist revolutions in Europe meant that the Soviet Union should focus on strengthening itself internally before attempting to spread its ideology, an idea that became known as "Socialism in One Country."[31] This pitted Stalin against both the previous position of the Bolsheviks and his greatest rival, Leon Trotsky, who thought that the nature of a world market meant that no socialist revolution could survive on its own in one country. Therefore, the Soviet Union needed to assist communists in other countries to ensure its long-term survival.[32] Trotsky's doctrine of "international socialism" eventually, as every communist knows, earned him an ice axe in the brain courtesy of one of Stalin's assassins.[33]

After winning against Trotsky, Stalin became one of the most brutal dictators in world history. He was like a hammer, treating his entire country as a nail in his relentless quest for personal power. He went after his rivals, then his own comrades, then everyone else he didn't like. He was aided by the fact that Lenin had abolished democracy and implemented Party dictatorship while ushering in politics of fear.[34]

Stalin's brutality against other leftists had terrifying consequences abroad. Leftists in Germany were weakened by infighting, and they were all subsequently shoved into concentration camps by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. In Spain, Stalin's zigzags with France and the UK and his policy of persecuting Trotskyists and anarchists left the Soviet-supported republican faction too busy fighting itself to fight the fascists, indirectly helping Franco win the war.[35] With each defeat, a socialist revolution in Europe became more improbable, and the chances of another World War starting seemed greater; thus, Stalin's government grew more and more oppressive each day. So not only was the great Soviet experiment failing, Stalin stepped in and ensured it would never recover.

Maoism[edit]

“”Every Communist must grasp the truth, 'Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.'

|

| —Mao Zedong, 1938.[36] |

Mao Zedong's particularly gruesome take on Marxism easily ranks as the most devastating attempt to establish a communist society, as far as the total number of human casualties is concerned. Having taken over mainland China in 1949, he developed a branch of Communist theory, commonly referred to as "Mao Zedong Thought", that was supposed to address China's specific circumstances. Since China was a mostly rural country without a solid industrial base, it lacked the distinct class of urban factory workers that, according to Marxism, was necessary to form any kind of revolutionary force. Hence, Mao's take on communism had two primary differences from others. First, Mao focused on the millions of impoverished Chinese peasants as the backbone of the revolution.[37] Additionally, Maoism called for a much greater emphasis on the organized military, resulting in Mao using the army as a hammer against his political enemies, as well as greater Chinese nationalism.[37]

Mao spent much of his rule flying by the seat of his pants in terms of ideology and planning. Mao initially tried following the Stalinist economic model, but he and his advisors reacted negatively to the consequential creation of a managerial and technocratic elite.[37] Deciding to focus on peasants instead, Mao ordered a vast industrialization program that was supposed to transform China's agrarian economy into a much more advanced one. This project, called the "Great Leap Forward", sought to create an industrial society that focused on manpower more than machines, hence the "backyard steel furnaces" phenomenon.[38] As a result of the botched attempt to shift peasants from farming to steelworking, China's economy crashed, and around 45 million people starved to death.[39] After being sidelined due to this failure, Mao eventually launched yet another attempt at a rapid societal transformation in a bid to re-establish himself as the undisputed leader of China. Starting in 1966, his so-called "Great Cultural Revolution" again toppled China into chaos, as a fanatic youth movement set out to destroy Chinese traditional culture and the supposed last vestiges of the old elites.[40] In practice, it was a reign of terror that consisted of completely random attacks against anyone and anything that drew the suspicion of the frenzied "Red Guards", among them no small number of their own operatives.

Apart from China itself, several Communist movements in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Latin America claimed an explicit adherence to Maoism. Despite significant political differences, Cambodia's Khmer Rouge was considered almost a recreation of Mao's Chinese Communist party (down to the extreme, culturally motivated purges).[41] However, many such parties are no longer exclusively agrarian in focus, placing a dual emphasis on both rural and urban workers.

"Dengism"[edit]

“”Socialism and market economy are not incompatible... We should be concerned about right-wing deviations, but most of all, we must be concerned about left-wing deviations.

|

| —Deng Xiaoping.[42] |

Since Mao had brought the country to the brink of ruin, Maoist ideology was mostly discredited as an actual guideline for governing the nation. His eventual successor, Deng Xiaoping, effectively abandoned it by promoting pragmatic developmental policies, so today's China is a booming capitalist economy ruled by an authoritarian oligarchy, which has recently been sliding pretty fucking close to totalitarianism.[43] However, because of Mao's status as a larger-than-life figure in Chinese politics, and especially the CCP, Maoism is still upheld as a part of "Deng Xiaoping Theory".[44]

It is essential to note that economic liberalization did not result in more political or civil freedoms for the Chinese people. Deng oversaw the Tiananmen Square Massacre, a brutal crackdown on student protesters, the political fallout of which transformed his reform agenda into a post-Soviet style wealth grab by members of the party.[45] The Chinese economy now represents the worst excesses of capitalism, combined with the old communist system's structural brokenness. China now relies heavily on aggressive jingoistic nationalism to motivate its people.[46]

Libertarian communism[edit]

Left communism and libertarian Marxism are forms of Marxism that leans away from the authoritarianism found in the Leninist lineage emphasize the anti-authoritarian bents in Marxism, with figures such as Rosa Luxembourg.![]()

Critical theory[edit]

The Frankfurt School and other critical theorists are closely associated with Marxism, but generally see less political activism.

Non-Marxist Communism[edit]

While Marxism is by far the most immediate association with communism, forms of communism that are not Marxist exist and have some popularity.

"Utopian socialism" (a term coined by Engels, as opposed to scientific) promotes the construction of communes separate from society. Charles Fourier was considered a utopian socialist and had an influence on the Paris Commune.

Anarchism has a storied history as it interplays with communism, and fusions exist. Anarcho-communism pushes for not just public ownership of means of production but also the dissolution of the state. Peter Kropotkin is perhaps the most well-known anarcho-communist theorist, along with Emma Goldman. Anarcho-syndicalists are very much related, and include the likes of Rudolf Rocker, Murray Bookchin, and Noam Chomsky. Wobblies are known for their anarchist leanings. The black bloc of the Russian revolution (such as Makhnovshchina,![]() the short-lived period of revolutionary Catalonia, and Rojava (depending on who you ask) are examples of anarcho-communism in practice.

the short-lived period of revolutionary Catalonia, and Rojava (depending on who you ask) are examples of anarcho-communism in practice.

Religious communism integrates religious teachings with socialist beliefs. Christian communism,![]() for example, uses the Gospels and the teachings of Jesus therein as inspiration for a communitarian life style.

for example, uses the Gospels and the teachings of Jesus therein as inspiration for a communitarian life style.

Communism as implemented[edit]

“”Human beings are born with different capacities. If they are free, they are not equal. And if they are equal, they are not free.

|

| —Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago[47] |

What was espoused by Karl Marx differs significantly from what has been put into practice. Indeed, there has never been (and may never be) a "pure" communist society based solely on Marx's ideas; the most visible "communist" states have been single-party states applying Lenin's theory. Much of this is undoubtedly attributable to the fact that Marx left a great deal of his work unfinished and that Vladimir Lenin engaged in a campaign to rectify this by making a complete worldview out of Marx's philosophy — what was later called Leninism (Marxism-Leninism, contrary to its name, was not developed by Lenin but instead by Stalin after Lenin's death[48]). However, Lenin also deviated a good deal from what Marx had said (as detailed above). There is a reason why even the Soviets started using the phrase "actually existing socialism" to describe themselves, after all...

General problems[edit]

Experience of the 20th century also showed that the vanguardist revolutionary method, as espoused by Lenin's misinterpretation of the dictatorship of the proletariat, conceived as a means of defending the revolution, led not to the destruction of the state but to its reinforcement and degeneration into state capitalism and totalitarianism. This has become rather a touchy subject to bring up.[49] This isn't the case for every leftist government: some have historically managed to stay respectful of rights and democracy (e.g., in Moldova![]() and Cyprus), and it is not uncommon for communist parties to govern as part of broader left-wing coalitions (e.g., the French Popular Front in the 1930s and the communist wing of the African National Congress). However, these governments and coalitions have all been constrained by liberal-democratic, non-communist constitutions guaranteeing free speech, free elections, and the right to dissent.

and Cyprus), and it is not uncommon for communist parties to govern as part of broader left-wing coalitions (e.g., the French Popular Front in the 1930s and the communist wing of the African National Congress). However, these governments and coalitions have all been constrained by liberal-democratic, non-communist constitutions guaranteeing free speech, free elections, and the right to dissent.

- The introduction of democratic government to communist dictatorships has been invariably followed by that country abandoning communism as its official ideology.[50] Well-known examples are Poland, Hungary, and Romania. However, after the breakup of communist states, not everything was sunshine and roses. For example, Yugoslavia descended into a series of bloody inter-ethnic wars. At the same time, Russia had to deal with Boris Yeltsin's incompetent economic reforms, which resulted in an economic collapse worse than the Great Depression.[51]

- The planned economies of Marxist-Leninist countries have proven themselves unable to match the levels of growth and economic benefits found in less strictly controlled economic systems. While the Soviet Union, post-Stalin, had the second-highest nominal GDP in the world and was a pioneer in the space program, its economy eventually stagnated by the 1970s, which forced the introduction of economic reforms by Mikhail Gorbachev.[52][53] Whatever remains of communism in countries like China and Vietnam has been deconstructed into authoritarian capitalism.[54][55] The states that followed this path now have market economies connected to global trade, but they are no less dictatorial. On the other hand, Laos, North Korea, and Cuba have not allowed very many market reforms. One can clearly see the state of their economies, with North Korea struggling to meet even the most basic needs of its citizens.

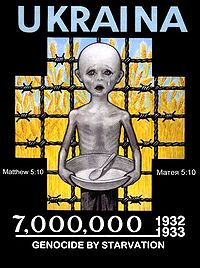

Crimes against humanity[edit]

Totalitarian communist governments have been responsible for many mass slaughters, often considered genocides. Most historians accept a rough number of around 20 million, including famine victims, for the Soviet Union and provisionally somewhere between 2 and 3 million for Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, of whom roughly half were executed outright. In Maoist China, there's still little consensus, and for the Great Leap Forward alone, estimates of excess deaths range from 15 to 40 million. Furthermore, it is certainly fair to suggest that for every one individual taken away and either deported, sent to a prison camp, or executed, there were likely many more who faced intimidating questioning by the secret police, lost their apartments, jobs, or life chances for education, and more still who lived in reasonable fear of these kinds of losses.[56]

Other examples of human rights violations and crimes against humanity include:

- Cuba under Fidel Castro

- North Korea

- The German Democratic Republic and the Stasi

- Yugoslavia Under Tito

- Romania under Nicolae Ceaușescu

And the list goes on and on.

Final remnants[edit]

As it stands, there are only a few remaining nation-states that proclaim themselves communist, and it is evident how well the judgment of history will handle them. These systems are:

- Castroism in Cuba: Cuba actually boasts a very high average life expectancy due to socialized health care(the spite of dilapidated hospitals[57]) and has evaded the issues of overpopulation (thanks to the country having one of the highest abortion rates in the world; the aforementioned very-high-average-life-expectancy can also be attributed to that[58]) and pollution that has plagued China. However, Cuba's economic gains have never materialized, partially due to a US economic and commercial blockade.[59] Nonetheless, Cuba can boast some of Latin America's highest living standards, especially when compared to other Caribbean countries.[60][61] Of course, this isn't exactly an achievement, considering the rest of the region was ruled by moronic tinpot military dictatorships, almost all backed by the United States, while Cuba received absurd amounts of Soviet funding.[62][63] Like North Korea, the loss of the Soviet Union and thus funding and a market for their goods regardless of quality only made Soviet-style communism harder for Cuba. The Cuban government is a dictatorship that holds many political prisoners in horrible conditions while brutally suppressing freedom of speech, all this even after their new president's accession.[64]

- Juche in North Korea: called a "mausotocracy" by Christopher Hitchens, this society insists that Kim Il-sung is the Eternal President of the Republic, despite his noticeable lack of pulse, heartbeat, respiration, or brain activity since 1994. His son and now grandson, therefore, are perpetually playing second fiddle as Supreme Leader. Despite its clear influences, North Korea has actually removed all references to communism from its constitution, and today, Juche is a bizarre mix of ultra-nationalism, militarism, and Kim worship. It has a horrifying human rights record.[65] And, of course, it's still regularly used for red-baiting: those who exhibit any kind of leftist ideas are often told to go to North Korea if they love socialism so much!

- Maoism with

Deng XiaopingXi Jinping Thought in China: it's basically "market socialism."[note 3] Despite having the fastest-growing economy on Earth, the Chinese industrial existence is, ironically, on par with the working conditions in Soho, which repelled Marx when he was initially writing Das Kapital. You could say that the Chinese system is the only form of "communism" that actually works, but considering their record on civil rights (think the Tiananmen massacre and the one-child policy), that might be a bit of a stretch. China claims to be going back into more Mao-inspired policies in the future. - Laos and Vietnam: still ostensibly Marxist-Leninist. Vietnam has gone in the direction of China's market socialism. Laos, at present, has only introduced limited market reforms.

Is communism at all workable?[edit]

It depends on what you mean by "communism" and what you mean by "workable."

Current status[edit]

While the 20th-century Marxist-Leninist states had some bright spots, like the Soviet Union's industrialization and investment in science and space exploration, they also left a trail of blood and pollution in their wake. Their legacy of failure is impossible to ignore. China can hardly be called communist anymore and now more closely resembles a far-right authoritarian state. Similarly, the Soviet experiment was destroyed by Stalin's brutality and put out of its misery by the Gorbachev reforms.

Previous experiments in communism, whether fundamentally capitalist (Jamestown, VA) or utopian (the Oneida community), lasted only for, at most, a couple of generations before being torn apart by internal dissent.[note 4] Besides, the confusion about communism and the politics of the Warsaw Pact community has stained the name of communism to the point that even if it was tweaked into a workable form, some other word for it would have to be found.

Not all post-communist states successfully transitioned into democracy and capitalist economies. For instance, many former Warsaw Pact states underwent economic shock therapy and massive privatization programs, which led to periods of massive wealth inequality, unemployment, and loss of social welfare. In other cases, communist politicians simply rebranded themselves as social democrats and continued to run the show, with many gobbling up former state-owned enterprises for themselves. Yugoslavia disintegrated into a series of wars over ethnic and religious lines, and Boris Yeltsin ran Russia like a circus by introducing widely unpopular economic reforms, creating a new class of oligarchs![]() and unemployment as high as 40%. These economic uncertainties, along with events such as the 2008 financial crisis and the current European refugee crisis, have led many disillusioned people to long for the good old days under communism and, in other cases, to elect authoritarian strongmen such as Russia's Vladimir Putin and Hungary's Viktor Orbán.

and unemployment as high as 40%. These economic uncertainties, along with events such as the 2008 financial crisis and the current European refugee crisis, have led many disillusioned people to long for the good old days under communism and, in other cases, to elect authoritarian strongmen such as Russia's Vladimir Putin and Hungary's Viktor Orbán.

Critics of communism tend to fault it for its hyper-idealistic egalitarianism, based on the assumption that a state set up to fade away is a sitting target for authoritarians and slackers and that there would be no incentive to excel in any given field. Besides, the planned economy aspects of Soviet Communism, in particular, have consistently failed due to an ideology that proved unable to react to the slightest outside changes.

Viability?[edit]

The question then becomes this: what does this "great apostasy" say about the viability of Marxism? Opinions run the gamut:

- Some (George Orwell, for example[note 5]) say that Marxism's highly theoretical and dogmatic nature can cause its more enthusiastic devotees to become isolated from the proletariat at large — thus almost ensuring that any successful communist takeover will result in a dictatorship of some sort.

- Some argue that the tendency of communists to only look at society in terms of classes and to only care about the well-being of the "underclass" while being highly dismissive, if not contemptuous, of those who fall into the category of the "overclass", nearly ensures mass slaughter and/or repression would come about by a communist takeover due to the obvious problems with declaring a good chunk of society is virtually "free game" during a revolution merely for being members of the wrong class.[note 6] Also, this analysis does not take individual rights into consideration but only what is good for the underclass as a whole, whose very nature is often conveniently defined by communist leaders themselves (i.e., often translating to "those who agree with us").[66]

- Some claim that while communism had its uses at the time, the nature of modern economies — even if you were able to separate the human rights issues — makes it quickly outdated and solely the domain of moonbats. Having full state control of the economy can be workable and even helpful when your economy is small and dysfunctional. Still, when it starts growing, the central bureaucracy grows increasingly incompetent at managing economic affairs. Command economies often follow the pattern of first causing mass deprivation and starvation, then growing rapidly with attendant increases in life expectancy, then stalling, then collapsing or stagnating, necessitating the introduction of market reforms.

- Some suggest that Marxism is by itself just a relatively harmless pile of bullshit, especially as it concerns economics. Still, it can easily be hijacked by a dictatorial methodology like Leninism so that when its economic methods do not work, anyone who tries to point out that the Emperor has no clothes on can be conveniently silenced.

- Some (significantly reduced in number since the Soviet gravy train derailed) continue to support Marxism's core ideas and work toward the proletarian revolution using a wide variety of methodologies, with a certain hope of a pure communist society to come.[note 7]

- Some reject Marxism in its original form but think the core ideas — such as class struggles (generalized into conflict theory) and the comparatively idyllic world spoiled by one of these classes' ascendancy — are still worthwhile. Indeed, Marxist historical analysis, a distinctly different beast from communism in and of itself, is generally considered a useful tool for understanding quite a bit of history[citation needed].

Also, although state-imposed collectivism did not work out so well, private corporations run as collectives[note 8] do slightly better than companies based on a more traditional hierarchy, and even if Marx was somewhat naive about economics (and, in hindsight, every economist from the 19th century and prior looks somewhat naive about economics: for example the labor theory of value, the discrediting of which forms the basis for much of the modern economic critique of Marxism, was not unique to Marxism by a long shot, being supported by the father of capitalism himself, Adam Smith) his contributions as a historian and pioneering work in the then-nascent field of sociology shouldn't be overlooked or understated. It's reasonable to look at the train wreck of communism in practice as an utter failure, but that doesn't mean there isn't anything to learn from it.

Communist or not?[edit]

Again, advocates of communism look at the failure of every attempt to implement communism and argue that those societies were not really communist - either for immediate, local reasons or for the blanket reason that none of them have taken place in advanced industrial societies, which (for Marx, at least) would doom them to failure, or attribute them to social conditions inherited from prior regimes. In most cases, communist governments didn't necessarily follow Marx's theories as set out, and corruption and cronyism were rampant; Marx certainly wouldn't have approved of that or the use of tactics by the governing authorities that he considered reserved for the use of the proletariat at large, such as expropriation.[67] However, Marx's antipathy towards the bourgeoisie was used as an excuse to kill millions (especially in China and Cambodia, but more famously Ukrainian country folk in the USSR) because they were branded "petty-bourgeois counter-revolutionaries" for the crime of looking cross-eyed at the nomenklatura.

Additionally, it might be worth looking at forms of libertarian Marxism and libertarian communism before generalizing history's bloody communist dictatorships as the whole of communism. To summarize, communism is a classless, "democratic" (Marx called for 'self-government of the commune' in response to Bakunin's accusations that he wished for a minority dictatorship) and international society. There are different theories as to how such a regime should be organized, for example:

- The anarcho-syndicalists and De Leonists wish for a Socialist Industrial Union.

- Mutualists (inspired by the ideas of Proudhon) wish for a non-capitalist free market (often claiming that the capitalist market can never have anything to do with 'freedom').

- Other socialists wish for a system of workers' councils (though these can often be compared to the syndicalist unions), as in the "soviets," which represented the working class in Russia until Lenin's coup d'etat. The workers had also taken over factories, instituting elected and recallable factory committees that ran them under their ultimate control before Lenin took over. Such "worker self-management" has also been a crucial part of socialism in both libertarian Marxist and anarchist tendencies or schools of thought. However, they are split into two camps: left communism and council communism. Council communism aims to use trade unions, political parties, and mass strikes to achieve socialism, while left communists believe such actions betray the working class's spontaneity.

The few examples when communism worked out relatively fine[edit]

- The Paris Commune

was an upheaval that took place in 1871. To this day, it remains a reference for the French left as a whole, as it advanced many major left-wing themes (feminism, secularism, direct democracy...). It remained pluralistic throughout, but in the context of open civil war, it eventually repressed those who overtly supported its enemies — who were much worse in that regard. It was a major influence on Karl Marx himself.[note 9] It lasted barely more than two months, as it was brutally crushed.

was an upheaval that took place in 1871. To this day, it remains a reference for the French left as a whole, as it advanced many major left-wing themes (feminism, secularism, direct democracy...). It remained pluralistic throughout, but in the context of open civil war, it eventually repressed those who overtly supported its enemies — who were much worse in that regard. It was a major influence on Karl Marx himself.[note 9] It lasted barely more than two months, as it was brutally crushed. - The communists and anarchists before and during the Spanish Civil War had created a very free and prosperous society, as recounted in George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia.

FrancoStalinists crushed them. Though it's worth noting that there was a rather nasty Red Terror,

crushed them. Though it's worth noting that there was a rather nasty Red Terror, so it wasn't a total success from a human rights point of view (even if they were better than the Whites).

so it wasn't a total success from a human rights point of view (even if they were better than the Whites). - In a similar vein, the Ukrainian Free Territory

had an anarcho-communistic government during the Russian Civil War. However, it was also destroyed militarily (not by the White Guards, even — in fact, the insurgent army fought Denikin's army successfully — but rather by the Bolsheviks themselves).[68]

had an anarcho-communistic government during the Russian Civil War. However, it was also destroyed militarily (not by the White Guards, even — in fact, the insurgent army fought Denikin's army successfully — but rather by the Bolsheviks themselves).[68] - The Yugoslav workers' self-management worked out for a little while.

- The Israeli kibbutzim

— however, as with anything involving Jews or leftism, there are about as many philosophies of how to do kibbutzim "right" as there are kibbutzim.

— however, as with anything involving Jews or leftism, there are about as many philosophies of how to do kibbutzim "right" as there are kibbutzim. - The Twin Oaks Community

is currently working right now.

is currently working right now. - Marinaleda,

a municipality in Spain, is doing surprisingly well.

a municipality in Spain, is doing surprisingly well. - In India, of all places, a communist government was elected in Kerala. The state has (through a combination of reasons, especially overseas remittances by expatriates and the communists moderating their policies in practice) flourished with relatively few missteps. Compared to much of the country, Kerala is relatively well-developed. Whether this is correlation vs. causation is still debatable. More on that here.

- The Zapatista Army of National Liberation,

aka EZLN, has been doing its thing in Chiapas since 1994, and its coffee cooperatives ensure that they're not going anywhere anytime soon.

aka EZLN, has been doing its thing in Chiapas since 1994, and its coffee cooperatives ensure that they're not going anywhere anytime soon. - Rojava,

despite being in a brutal civil war, is doing pretty well for itself.

despite being in a brutal civil war, is doing pretty well for itself.

Suppose any conclusions can be drawn from what these examples all have in common. In that case, working communism needs a minimum of top-down authority (all examples are varied ways of "bottom-up") and to avoid being crushed by any self-declared communists surrounding it who have a more "top-down" approach to things.

Derivative philosophies[edit]

Besides communism, there are many different ideologies and schools of thought based on Marx's views.

There still is a great deal academics find useful in Marxism as a research tool. For example, Marxist historians focus on economic relationships and progress in history and believe financial motivations and class consciousness to be the most important underlying causes of change (or, in layman's terms, money, in fact, does make the world go round, but you'll always get screwed by the rich man). Marxist history is a school of social history, focusing primarily on the conditions of the (working class) majority rather than on the deeds of kings and leaders.[note 10] There are similar Marxist forms of sociology and cultural theory. Marx's outline of how capitalism works is still taught in economics, though it's not considered the whole story.

There are many variants of the idea of some underclass being exploited or oppressed by some upper class and the need for that underclass to unite and make a revolution. The second wave of feminism most active in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as radical feminism, viewed women as the underclass. Nationalism,[note 11] particularly among colonized peoples, may view the colonized nation as the underclass; an example of this is the strong nationalistic elements in the ideology of left-wing governments in former territories occupied by empires. This often leads to the strange result of leftists supporting nationalist movements in far-off places that do things they would be up in arms against were they to happen in their own country, up to and including the suppression of communist opposition. Identity politics abstracts the idea entirely and allows the selection of an arbitrary underclass, thus giving rise to such phenomena as "ethnic studies," "queer studies," "disabled studies," etc. The feminist, black militant, and gay rights movements of the later 1960s and 1970s were informed by a Marxist outlook, including the Black Panthers, as David Horowitz loves to remind us of frequently. So scary.

Libertarian communism is an elimination of the state similar to Marxist communism, but it claims to be a part of the libertarian family.

Communism and religion[edit]

Marx on religion[edit]

Karl Marx famously said that religion was "the opiate of the people." Or, in full:

“”Religion is, indeed, the self-consciousness and self-esteem of man who has either not yet won through to himself, or has already lost himself again. But man is no abstract being squatting outside the world. Man is the world of man—state, society. This state and this society produce religion, which is an inverted consciousness of the world, because they are an inverted world. Religion is the general theory of this world, its encyclopedic compendium, its logic in popular form, its spiritual point d'honneur, its enthusiasm, its moral sanction, its solemn complement, and its universal basis of consolation and justification. It is the fantastic realization of the human essence since the human essence has not acquired any true reality. Therefore, the struggle against religion is indirectly the struggle against that world whose spiritual aroma is religion. Religious suffering is the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering at one and the same time. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. Therefore, the criticism of religion is in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.

|

Of course, these were simply Marx's beliefs. Religious socialism still exists, as the system of communism is itself not opposed to religion, and indeed, many Christians with socialist sympathies have drawn on the words of Jesus himself in defense of socialism and other anti-capitalist social teachings. Marx did not advocate the banning of religion, instead arguing that it is merely a way to cope and see something bright at the end of the tunnel when one is faced with the injustices of feudal and capitalist society. He says that the criticism of religion is thus the criticism of the conditions that breed it. In an interview later on, Marx dismissed violent measures against religion as "nonsense" and stated the opinion (he specified that it was an opinion) that "as socialism grows, religion will disappear. Its disappearance must be done by social development, in which education must play a part."

As for the phrase itself, opium in Marx's time was an important painkiller, a source of extraordinary visions for 'opium eaters,' the cause of important conflicts such as the Opium Wars, and also used by parents to keep their children quiet. Marx was likely alluding to all of these.

Despite Marx's view that religion could co-exist with communism, many communist states have cracked down on religious groups or banned them altogether. For example, the Russian Orthodox Church had for hundreds of years been a powerful institution in Russia and had many ties to the former czarist regime. Hence, in the mind of the Soviet leaders, the church formed an institutional threat to its existence and had to be controlled. Albania under Enver Hoxha banned religion altogether, claiming that it had kept Albania back for many years. China tightly regulates religion within its borders, barring the Roman Catholic Church and other churches not under the direct control of the state, leading to a burgeoning Evangelical Protestant "house church" movement.

These evolving, increasingly hostile attitudes can be read in parallel with the evolution of Martin Luther's opinions toward the Jews. Initially, Luther viewed the Jews roughly the same way that Marx viewed religion, arguing that the Jews did not convert to Christianity due to their rotten treatment at the hands of the corrupt Catholic Church, leaving them with a terrible impression of the faith. When the Jews refused to give up their religion in favor of Lutheranism, Luther became more overtly anti-Semitic and started calling for the synagogues to be burned. The growing antipathy of the communists towards religion can be interpreted in much the same way. The initial idealism concerning the replacement of religion with communism faded in the face of religion having proved itself far more challenging to extinguish.

Religion in communism[edit]

Marxism, despite generally rejecting the supernatural, carries distinct millennial overtones about it. Although all sectors of Christianity at least nominally oppose orthodox Marxism due to its materialism, the non-millennial denominations have been most vocal in their opposition to communism. The Catholic Church, in particular, has explicitly condemned "secular messianism" as a form of millennialism, specifically citing communism as an example.[69][70]

Communism and rhetoric[edit]

Communists are frequently alleged to be the true force behind the UN or some other scheme for a New World Order or one world government. These conspiracy theories are sometimes tied into anti-Semitism and the idea of an international Jewish conspiracy because many Jews were aligned with leftist politics. Its latest incarnation is the Cultural Marxism conspiracy theory favored by alt-right and Gamergate wingnuts.

Wingnuts also ascribe to the word "communism" quite a different meaning: "Any policy or belief that is insufficiently right-wing for my taste," or "any policy which promotes racial equality and integration." You can thank Joseph McCarthy for that.

In response to the perceived threat by the USSR, the USA engaged in acts of gunboat diplomacy, especially in its sphere of influence. This meant it toppled left-wing nationalists such as Mohammad Mosaddegh,![]() Jacobo Árbenz,

Jacobo Árbenz,![]() and Salvador Allende to prevent them from cozying up with the Soviets and tolerated corrupt, authoritarian dictators such as Augusto Pinochet and Suharto, as long as they were anti-communist. This has ramifications and blowback even after the Cold War ended, with the Islamic Republic of Iran and Al-Qaeda both having their roots resulting from US intervention against communism and Soviet influence.

and Salvador Allende to prevent them from cozying up with the Soviets and tolerated corrupt, authoritarian dictators such as Augusto Pinochet and Suharto, as long as they were anti-communist. This has ramifications and blowback even after the Cold War ended, with the Islamic Republic of Iran and Al-Qaeda both having their roots resulting from US intervention against communism and Soviet influence.

Quotes about communism[edit]

“”Communism was a gigantic façade, and the reality concealed behind it was the sheer drive for power, for total power as an end in itself. The rest was merely instrumental—a matter of tactics and some necessary self-restrictions to achieve the desired end.

|

| —Leszek Kołakowski.[71] |

“”[O]nly one so-called revolution puts itself above God, insists on total control over the peoples' lives, and is driven by the desire to seize more and more lands... I have one question for those rulers: If communism is the wave of the future, why do you still need walls to keep people in and armies of secret police to keep them quiet?

|

| —Ronald Reagan, 1983.[note 12][72] |

“”The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to other working-class parties. They have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole. They do not set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement.

|

| —Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto |

“”How do you tell a communist? Well, it's someone who reads Marx and Lenin. And how do you tell an anti-Communist? It's someone who understands Marx and Lenin.

|

| —Attributed to Ronald Reagan.[73] |

“”One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words 'Socialism' and 'Communism' draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, 'Nature Cure' quack, pacifist, and feminist in England.

|

| —George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier |

“”Contemporary communism is not only a party of a certain type, or a bureaucracy which has sprung from monopolistic ownership and excessive state interference in the economy. More than anything else, the essential aspect of contemporary communism is the new class of owners and exploiters.

|

| —Milovan Djilas |

Pinko commie[edit]

"Pinko commie" is a phrase used in parodies or mockeries of opponents of communism, particularly those from the McCarthy era.

"Pinko" refers to someone who is not themself a communist but who sympathizes with communism (hence "pink", not quite red). Consequently, "pinko commie" is arguably (logically) an oxymoron.

The phrase started gaining popularity as a description of the communist movement as early as the 1930s.[74]

Notable communists[edit]

- The Cambridge Five,

Soviet infiltrators in Britain

Soviet infiltrators in Britain - Fidel Castro, former dictator of Cuba 1959-2008

- Tony Cliff, British Trotskyist who influenced Christopher Hitchens

- Daniel De Leon, American socialist whose views were more akin to anarcho-syndicalism

- Farrell Dobbs, Teamsters' union activist, leader of the Minneapolis General Strike of 1934

- Friedrich Engels, dictator of writing

- André Gide, (disillusioned) author best known for the "lifeboat dilemma"

- Antonio Gramsci, Marxist philosopher, inventor of "cultural hegemony"

- Che Guevara, henchman of Castro, t-shirt icon

- Woody Guthrie, folk singer

- Dorothy Healey, union activist, radio host (small "c" communist after 1973)

- Eric Hobsbawm, a famed British Marxist historian and whitewasher of Soviet crimes against humanity

- Enver Hoxha, dictator of Albania, 1944-1985

- Alger Hiss, US government official and alleged Soviet Spy

- Jim Jones, cult leader of the People's Temple

- Kim Jong-il, dictator of North Korea 1994-2011

- Kim Jong-un, dictator of North Korea 2011-present

- Karl Kautsky, an early critic of the Bolsheviks

- Yuri Kochiyama, a controversial Japanese-American civil rights activist

- Arthur Koestler, (disillusioned) author and pseudohistorian whose best-known work is Darkness at Noon

- Pyotr Kropotkin, zoologist and founder of Anarcho-communism.

- Vladimir Lenin, dictator of the USSR 1917-1924

- Rosa Luxemburg, German communist activist

- Karl Marx, the one who got the ball rolling

- Mengistu Haile Mariam, dictator of Ethiopia

- Ho Chi Minh,

dictator of Vietnam 1945-1969

dictator of Vietnam 1945-1969 - Pablo Picasso, painter

- Pol Pot, dictator of Cambodia 1975-1979

- Pete Seeger, folk singer

- Joseph Stalin, dictator of the Soviet Union 1924; 1927-1953

- Kim Il-sung, dictator of North Korea, 1948-1994

- Josip Tito, dictator of Yugoslavia, 1944-1980

- Leon "Snowball" Trotsky, tried to get the chairman role in Soviet Union but failed and traveled to Mexico, where he lived until his death.

- Richard Wright, (disillusioned) author whose works include Black Boy, Native Son, and The Outsider

- Mao Zedong, dictator of China 1949-1976

- Abdullah Öcalan, former Marxist turned libertarian socialist after reading the works of Murray Bookchin

- John Lennon, the dictator of the band called the Beatles

See also[edit]

- Anti-Fascist Protective Wall (commonly known as the "Berlin wall")

- Command economy

- Equality – The general basis of the projected communist society, in which all permanent hierarchies are abolished, including that of class.[note 13]

- Tiananmen Square Massacre

- Jewish Bolshevism — an anticommunist, anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that accuses Jews of causing the Russian Revolution

- John Birch Society – the United States' most prominent anti-Communist organization (They didn't get the memo). A common figure of fun, even back then.

- List of forms of government

- Moral panic

- Slavoj Žižek – anti-Stalinist, philosopher, and filmmaker

- Socialism

External links[edit]

- Marxists.org, your one-stop shop for Marxist theory

- Libcom.org The libertarian, anarchist variety.

- International Journal of Zizek Studies

- Museum of Communism

- Jokes from Ronald Reagan on Communism.

- Quotes on Communism from Liberty Prime.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ This was when Marx made his famous remark that if their politics represented Marxism, he wasn't a Marxist.

- ↑ It's essential to explain that this "dictatorship" would be the democratic decision-making by the workers and stood in contrast to the "dictatorship of the bourgeois," where the decision-making is made in a mostly authoritarian manner by the owner class. The term was used because before a truly class- and state-less society was brought upon, the workers would be co-opting state power (which was seen as inherently authoritarian) to enact their democratic decision-making.

- ↑ If it can even be called that, as market socialism relies on democratic enterprises in a market system.

- ↑ The last such movement of any significance, the Shakers, is on the verge of dying out, with only two members left in its last known community in Maine.

- ↑ In his book The Road to Wigan Pier, he compared Marxism to Catholicism, with the Hegelian dialectic taking the place of the Trinity.

- ↑ However, this criticism would only apply to either authoritarian communists or communists who advocate for a violent revolution. Communists who are non-violent and non-authoritarian would usually be exempt from this.

- ↑ Similarly, some Christians continue to work toward the elimination of all sin to bring about a thousand golden years on Earth before Jesus returns to cast sinners into the Lake of Fire.

- ↑ Examples of companies run along collective lines include REI, King Arthur Flour, and the consortium responsible for Parmeggiano Reggiano cheese.

- ↑ It inspired his view of the dictatorship of the proletariat. But according to him, one of the causes of its failure was that the Commune wasn't repressive enough towards its enemies. In turn, his critique influenced Lenin, so this was maybe how communism's reputation for authoritarianism started in the first place.

- ↑ When this is applied to periods of history from which the only surviving records are of said kingly deeds, this must result in at least some speculation, which perhaps opened the door for the historical negationism so common among communist historians (most notably in the Soviet Union, where people questioning official Party history could be conveniently clapped in the gulag).

- ↑ For which Marx, incidentally, had nothing but disdain

- ↑ Like, really, he actually did say this.

- ↑ However, without due diligence to proper farm management, some animals wind up more equal than others.

References[edit]

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

- ↑ History of Communism and Early Common Ownership[1]

- ↑ Communism. Business Dictionary

- ↑ Marxist Stage Theory. Learn Economics Online.

- ↑ The War Between Capital and Labor Sage American History.

- ↑ The Downfall of Communism. ThoughtCo.

- ↑ Communist Countries 2019

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Chinese economic reform.

- ↑ Vietnam-style reform would mean big changes for North Korea Reuters

- ↑ Explainer: The state of Raul Castro's economic reforms in Cuba Reuters Apr 16, 2018

- ↑ DeVore, Irven (1969). Man the Hunter. Aldine Transaction. ISBN 978-0-202-33032-7

- ↑ Livia Gershon (October 26, 2018). "When Communes Don't Fail". JSTOR Daily. Quote: "Communal living in the service of building a better world has a long history in the West. Metcalf writes that the first intentional community in recorded history was Homakoeion, created by Pythagoras in 525 BCE. The members tried to create an ideal society, though we don’t know much about what that meant to them other than that they gave up private property and meat, and were interested in numerology. Early Christians lived communally."

- ↑ R. B. Rose, Gracchus Babeuf: The First Revolutionary Communist (1978) (According to Wikipedia)

- ↑ The Programme of the Parti Ouvrier. Marxists.org

- ↑ Marxism. Marxists.org

- ↑ Communism after Marx. Britannica.

- ↑ Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League Karl Marx. 1850. London.

- ↑ The Programme of the Parti Ouvrier

- ↑ The Communist Manifesto at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Whether Das Kapital be an economic treatise or the ravings of a nut is a hotly debated question.

- ↑ Ukraine nationalists tear down Kharkiv's Lenin statue. BBC News.

- ↑ The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky "How Kautsky Turned Marx Into A Common Liberal"

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism.

- ↑ Menshevik. Britannica.

- ↑ 1917 Constituent Assembly in Russia. Spartacus Educational.

- ↑ Joseph Stalin. "Quotes about Joseph Stalin". Wikiquote.

- ↑ Who's Who — Benito Mussolini Firstworldwar.com

- ↑ 99 years since Rosa Luxemburg was murdered and dumped in a Berlin canal. The Local.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Polish–Soviet War.

- ↑ How Joseph Stalin became the leader of the Soviet Union. Daily History.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Socialism in One Country.

- ↑ Trotskyism. Britannica.

- ↑ What is a Trotskyist? BBC News.

- ↑ Lenin tilled soil for future purges. Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ The Spanish Revolution Betrayed. In Defense of Marxism.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Maoism. Britannica.

- ↑ Great Leap Forward. Britannica.

- ↑ Dikötter, Frank (2010): Mao's Great Famine. New York: Walker & Company, 2010.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Great Cultural Revolution.

- ↑ Maoism marches on: the revolutionary idea that still shapes the world. The Guardian.

- ↑ Deng Xiaoping. Wikiquote.

- ↑ The charts show how Deng Xiaoping unleashed China’s pent-up capitalist energy in 1978. Quartz.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Deng Xiaoping Theory.

- ↑ How the Tiananmen Massacre Changed China, and the World Ping, Hu. China Change June 2, 2015.

- ↑ How Tiananmen changed China — and still could Twining, Dan. Foreign Policy. 6.4.9

- ↑ The Gulag Archipelago and the Wisdom of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Marxism–Leninism.

- ↑ Lessons from a century of communism. Washington Post.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Revolutions of 1989.

- ↑ Nolan, Peter (1995). China's Rise, Russia's Fall. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-12714-5.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Era of Stagnation.

- ↑ Stagnation in the Soviet Union. Alpha History.

- ↑ China marks 40 years of economic liberalization. Deutsche Welle.

- ↑ The story of Viet Nam's economic miracle. World Economic Forum.

- ↑ Strauss, Julia (2013-12-16). "Communist Revolution and Political Terror". Oxford Handbooks Online. doi

:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199602056.013.020.

:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199602056.013.020.

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/28/world/americas/in-cuba-an-abundance-of-love-but-a-lack-of-babies.html

- ↑ Cuba estimates total damage of U.S. embargo at $116.8 billion Reuters

- ↑ Caribbean communism v capitalism The Guardian.

- ↑ http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr14-report-en-1.pdf

- ↑ Soviet aid to Cuba: $11 million a day UPI Jim Anderson. 1983.

- ↑ Soviet Aid to Cuba New York Times 1973.

- ↑ Cuba Human Rights Watch

- ↑ North Korea Human Rights Watch

- ↑ http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2016/03/oh-good-were-arguing-whether-marxism-works.html

- ↑ The Communist Manifesto, chapter 2.

- ↑ afaq (11/12/2008). "Why does the Makhnovist movement show there is an alternative to Bolshevism?".

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1.2.7.1.9.676.

- ↑ Pius XI, encyclical Divini Redemptoris. [3]

- ↑ Communism Wikiquote

- ↑ Remarks at a Ceremony Marking the Annual Observance of Captive Nations Week

- ↑ Ronald Reagan. Brainy Quote.

- ↑ Safire, William (1991) Coming to Terms, Doubleday, New York, ISBN 9780385413008

KSF

KSF