Conspiracy theory

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 35 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 35 min

| Some dare call it Conspiracy |

| What THEY don't want you to know! |

| Sheeple wakers |

“”Modern political religions may reject Christianity, but they cannot do without demonology. The Jacobins, the Bolsheviks and the Nazis all believed in vast conspiracies against them, as do radical Islamists today. It is never the flaws of human nature that stand in the way of Utopia. It is the workings of evil forces.

|

| —John Gray, political philosopher[1]:25 |

“”Humans just lead short, boring, insignificant lives, so they make up stories to feel like they're a part of something bigger. They want to blame all the world's problems on some single enemy they can fight, instead of a complex network of interrelated forces beyond anyone's control.

|

| —Pearl, Steven Universe, |

A conspiracy is a secret plan to achieve some goal, whose members are known as conspirators. A conspiracy theory originally meant an idea that an event or phenomenon was the result of conspiracy. However, since the mid-1960s, it has often been used to denote ridiculous, misconceived, paranoid, unfounded, outlandish, or irrational speculative theories.[2]:16[3][4]:2,140[5]:66 It is therefore undesirable to refer to theorizing about a documented conspiracy as a "conspiracy theory".

Most conspiracy theories are outlandish and far-fetched. They usually involve operations on such a large scale that it's essentially impossible to keep them secret, and the events cited as proof of the conspiracy often have a very simple explanation (which is usually far simpler than the one given by the theorists). They also tend to make claims about events that happen outside the realm of observation, making it impossible to definitively prove that said conspiracies aren't happening. This is why, despite their implausibility, they manage to be so popular and appealing. Many conspiracy theories also strain credulity, and are not necessarily meant to be believed, but rather function as smear campaigns.[6]:61

Conspiracy theories tend to be completely self-sealing. Any attempt to deny, debunk, or present evidence against the conspiracy will be viewed as an effort by the conspirators to "cover up the truth", and the lack of evidence in support of the conspiracy is viewed as proof that the cover-up is successful, as proof that "THEY" are trying to "conceal the truth". The flood of conspiracy theories results in more plausible theories getting lost in the noise of newsworthy but disingenuous ideas such as the New World Order or the Moon landing hoax. Not everyone involved in a conspiracy necessarily knows all the details; in fact, sometimes none do. Not that this troubles most conspiracy theorists, of course.

For all the cranks shrieking about bread and circuses, widespread conspiratorial thinking actually threatens to become not just a means of winning political office, but also a way to govern through real misdirection of public attention.[7]

Scope and rationality[edit]

“”There is no group of people this large in the world that can keep a secret. I find it comforting. It's how I know for sure that [we're not] covering up aliens in New Mexico.

|

| —CJ Cregg on government[8] |

Many conspiracy theories fall into the self-refuting idea fallacy. Some commentary:

"A conspiracy theory is the idea that someone, or a group of someones, acts secretly, with the goal of achieving power, wealth, influence, or other benefit. It can be as small as two petty thugs conspiring to stick up a liquor store, or as big as a group of revolutionaries conspiring to take over their country's government."[9]:9

"Conspiracy theories as a general category are not necessarily wrong. In fact, as the cases of Watergate and the Iran-Contra affair illustrate, small groups of powerful individuals do occasionally seek to affect the course of history, and with some non-trivial degree of success. Moreover, the available, competing explanations — both official and otherwise — occasionally represent dueling conspiracy theories, as we will see in the case of the Oklahoma City bombing… [but] there is no a priori method for distinguishing warranted conspiracy theories (say, those explaining Watergate) from those which are unwarranted (say, theories about extraterrestrials abducting humans)."[10]

"A conspiracy theory that has been proven (for example, that President Nixon and his aides plotted to disrupt the course of justice in the Watergate case) is usually called something else — investigative journalism, or just well-researched historical analysis."[11]:17

"Conspiracy theory is thus a bridge term — it links subjugating conceptual strategies (paranoid style, political paranoia, conspiracism) to narratives that investigate conspiracies (conspiratology, conspiracy research, conspiracy account). Conspiracy theory is a condensation of all of the above, a metaconcept signifying the struggles of the meaning of the category. We need to recognize that we are on the bridge when we use the term."[12]:6

"Most conspiracy theories don't make sense nor withstand any scrutiny. They usually involve operations so immense that it's basically impossible for them to be kept secret, and all the proof given by conspiracy theorists usually have a very simple explanation (usually much simpler than the explanation given by the theorists)."[13]

"...conspiracy theories are deeply attractive to people who have a hard time making sense of a complicated world and who have no patience for less dramatic explanations. Such theories also appeal to a strong streak of narcissism: there are people who would choose to believe in complicated nonsense rather than accept that their own circumstances are incomprehensible, the result of issues beyond their intellectual capacity to understand, or even their own fault."[14]

Theories about conspiracies and conspiracy theories[edit]

| —John Oliver[15] |

The term 'conspiracy theory' has been used by the media to denote grand-scale conspiracy theories involving thousands of conspirators, as well as much more plausible ones, such as the Nazis themselves starting the Reichstag fire,[16]:457 Al Capone being behind the Saint Valentine's Day massacre, or the Dreyfus affair.[17] Because of this, some scholars have made efforts to distinguish plausible "theories about (real) conspiracies" from those that are little more than incoherent, paranoid ramblings typical of "conspiracy theories". One such effort is to call them theories of conspiracy,[18] while another is to separate the broad concept of conspiracy theories into the categories of 'warranted' and 'unwarranted'.[10]

Warranted conspiracy theories tend to be small in scope; requiring only a small group to carry out or be relatively easy to cover up. A crucial litmus test is whether any of those who must have been involved or in the know has ever leaked information. A recurring feature of baseless conspiracy theories is that they involve ridiculously large numbers of people, not one of whom ever betraying the conspiracy. The Watergate scandal was busted in part due to leaks provided to The Washington Post by Mark "Deep Throat" Felt.[19] The more people who are required to be "in" on a conspiracy, the less likely it is that the conspiracy will remain secret, and the more certain it becomes that the absence of a leak indicates that the conspiracy does not exist.

In 2016, David Robert Grimes published an analysis that compared the probability of maintaining conspiratorial secrecy vs. the number of conspirators and the length of time that the conspiracy has existed.[20] To assess the likelihood of conspiracies failing to maintain secrecy, Grimes used three real world conspiracies that were later exposed and estimated the number of people with knowledge of the secrets and the length of time that the secrets were maintained: the NSA PRISM spying (exposed by Edward Snowden), the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation forensic scandal.[20] Using this information, Grimes estimated a 95% chance failure for the following conspiracies and durations:[20]

- Moon landing hoax (3.68 years)

- Climate change fraud (26.77 years, counting scientists only; 3.7 years, counting scientific bodies)

- Vaccination conspiracy (34.78 years, counting CDC/WHO only; 3.7 years, counting scientific bodies)

- Suppressed cancer cure (3.17 years)

Classification of conspiracy theories[edit]

In his book A Culture of Conspiracy, Michael Barkun[21][22] (a political scientist specializing in conspiracy theories and fringe beliefs) defines three types of conspiracy theories:

- Event conspiracy: In which a conspiracy is thought to be responsible for a single event or brief series of events, e.g. JFK assassination conspiracies.

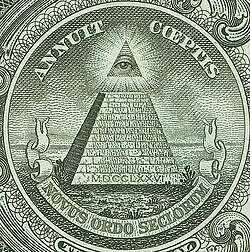

- Systemic conspiracy: A broad conspiracy perpetrated by a specific group in an attempt to subvert government or societal organizations, e.g. Freemasonry.

- Super-conspiracy: Hierarchical conspiracies combining systemic and event conspiracies in which a supremely powerful organization controls numerous conspiratorial actors, e.g. the New World Order or Reptoids controlling a number of interlocking conspiracies.[23]

Unified conspiracy theory[edit]

“”When I was younger, I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I've believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.

|

| —Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland |

| —Milhouse, The Simpsons, "Grandpa vs. Sexual Inadequacy" |

The unified conspiracy theory, popular among crank-magnetism types, posits that reality is controlled by a single evil entity that has it in for them. It can be a political entity, like "The Illuminati", or a metaphysical entity, like Say-tan Satan, or a racial group, like the Jews, especially if the crank magnet has racist views, but this entity is responsible for the creation and management of everything bad.

The term 'unified conspiracy theory' is a bit of a misnomer, as it is unified in the same way that a dumpster fire is unified: it's a dumpster, it's full of garbage, and it's inflammatory (in the case of the conspiracy theory, or it's just flaming in the case of the dumpster). Elements of the unified conspiracy theory are often thrown in willy-nilly with, at best, ephemera holding them together.

Michael Barkun coined the term "superconspiracy" to refer to the idea that the world is controlled by an interlocking hierarchy of conspiracies. Similarly, Michael Kelly, a neoconservative journalist, coined the term "fusion paranoia" in 1995 to refer to the blending of conspiracy theories of the left with those of the right into a unified conspiratorial worldview.[26] Also similarly, James McConnachie and Robin Tudge[note 1] have coined the term mega-conspiracy theory to refer to conspiracy theories that do not refer to specific events but are amalgamations of other conspiracy theories or ones that involve a demonized group that allegedly has a master plan for controlling the world.[27]

Despite all the mental hurdles this type of theory would require one to jump, it's one of the most common types out there[note 2] and is usually religious in nature. One reason for this could be that if your faith starts to dwindle due to a large amount of scientific evidence that undermines it, vehemently claiming that the scientific bodies responsible for these discoveries are working for the Devil is a great way to not only regain your faith, but also reinforce it.

When facts appear to threaten one's favorite conspiracy theory, creating a superconspiracy can be very useful as a way of dismissing them as 'part of the cover-up'. It's also worth noting that conspiracies rely on secrecy among the conspirators, so the more people who are in on the conspiracy, the more unlikely it is that it actually exists. It is akin to Benjamin Franklin's maxim, "Three may keep a Secret, if two of them are dead."[28]

Structure[edit]

Conspiracy theory checklist[edit]

“”Once you're forced to hypothesize whole new technologies to keep your conspiracy possible, you've stepped over into the realm of magic. It demands a deep and abiding faith in things you can never know.

|

| —S G Collins[29] |

We don't count on being able to "convert" conspiracy theorists. However, we have some very basic (read: kindergarten-level) questions which any self-respecting conspiracy theorist should really take the time to reflect on. These include:

Logistics[edit]

- How large is the supposed conspiracy?

- How many people are part of this conspiracy?

- Are there enough of them to carry out the plan?

- What infrastructure and resources does it need?

- How much time and money did it take and where did this money come from?

- If there are many thousands of conspirators, how are they organized?

- Where are the secret conferences held?

- How do they keep track of membership?

- If they are organised through known channels or entities, how do they keep non-members who work there from uncovering the conspiracy?

For instance, the Nazis pulling off the Reichstag fire only required a handful of men and minimal amount of money, while faking the Moon landing would require tens of thousands of co-conspirators and untold sums of money to pull off; the rock samples alone might require a decade to forge. And as for the supposed Titanic-Olympic swap, it would have called for paying off dozens upon dozens of Harland & Wolff workers as well as White Star Line employees to keep hush about renaming both ships over what amounts to a maritime fender-bender the RMS Olympic got involved in.

This is not to say that a massively large project cannot remain secret: the Manhattan Project created a whole multimillion-dollar industrial infrastructure which involved well over 100,000 personnel and managed to remain outside of the public eye basically until the people running it decided to go public in the most explosive way imaginable. But even that only had to be kept secret for four years and required massive amounts of resources to be kept secret; morale was low as people thought they were being told to waste time. For instance, several people were basically told "wave this device around the laundry room and tell someone if it starts clicking", but were never really told why. The project was amenable to the kind of compartmentalization that makes keeping large-scale conspiracies secret comparatively easy (even if you are running a factory with thousands of employees, if they don't know why they're doing what they're doing, then they can't really spill much), but this compartmentalization resulted in a lot of inefficiencies and personnel performing redundant tasks without much possibility for a clever employee to recommend a simpler solution. In the end this wasn't even secret to the people it needed most to be kept secret from (i.e. foreign powers like the Soviets) — to say nothing of the fact that you could probably have pieced together its existence from a number of open sources (e.g. noticing the significant drop in the number of American nuclear physicists who published articles during the period — a sign that they had been reassigned to Manhattan). The Soviets were aware of this as it happened, and at about the same time their own publications in the field started not to be published in accessible journals — a sign that they knew.

A conspiracy that allegedly encompasses an entire ethnic or religious group might suggest that all people in that group are co-conspirators irrespective of age, location, class, and occupation. The persons exposing the alleged conspiracy can ignore that the behaviour is contrary to the stated morality of their religion, that alleged gains from the conspiracy arise from legitimate activities such as commerce and the honing of talent, and that persons not reliable in well-honed and secretive plot (like infants, the senile, lunatics, idiots, and drunks) are part of the conspiracy. The conspiracy theory may hold that opposing interests within that group (such as plutocrats and Communists alike) are identical and that individual piety or charity within the group toward others (such as with the support of civil rights for African-Americans) is cover for far worse. The supposed Jewish conspiracy for world domination persists in fringes in the West even though the Jews have clearly shown that they too could be victims of a conspiracy far more insidious and destructive than anything imaginable in the forgery Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. Until the system that sponsored it was defeated, the Holocaust was undeniably one of the most effective conspiracies to have ever existed due to a tightly-knit apparatus competent at repression, hate-mongering propaganda, secrecy, deflection, and dedicated ruthlessness. The Nuremberg trials and subsequent tribunals exposed a genuine conspiracy of mass murder.

Benefits[edit]

- Who gains what from the conspiracy and for what price?

- If the conspiracy causes indiscriminate harm, how are its proponents protected from this harm?

- Is this the easiest way of gaining it? If not, why was it chosen over the easiest way?

- If it is an old conspiracy — who gains what from maintaining it?

This form of logic dates back to antiquity, where it was summed up by the Latin phrase cui bono, or "who benefits?" For example, the Nazis used the Reichstag fire to scapegoat the communists, it is considered an important factor in their rise to power, and it is hard to imagine that there was an easier way to do it, so they were likely the ones who started the blaze (although historians are still debating the issue to this day). Conversely, while faking the Moon landing might have been a way to have something to show for the Apollo project, the simpler solution would have been to actually land on the Moon. Also, Richard Nixon is dead, and no one in power has any reason to care about making sure everyone thinks we went to the Moon while he was president. For conspiracies to harm people, such as withholding the cure for AIDS or cancer, this could be countered by simply pointing out that even world leaders die of cancer. Asking such questions can also distract from actually focusing on the evidence, and lead to some pretty absurd conclusions. For example, regarding the assassination of JFK, "were who benefited the primary question, Aristotle Onassis would be a legitimate suspect. In fact, Onassis is targeted in one widely circulated conspiracy manuscript."[30]

Exposure[edit]

- How likely is it to remain covered up if it has gone on for a long time?

- If there are thousands of conspirators, and the conspiracy has gone on for decades, why have none of them defected?

- If there are defectors, why have none of them provided inside information?

- If many conspirators are dead, why have none of them told the truth on their deathbeds, or in their wills?

- There are many intelligence agencies associated with rival nations, with the ability to expose secrets. If, say, the United States government is running a global conspiracy, why have the French, Russian, or Chinese intelligence agencies never revealed it, to cause a major scandal in the United States (if all intelligence agencies are involved, see #2)? If they have, when and where did they do so?

With government-based conspiracy theories, one can have issues with the fact there are things about WWI, 100 years ago, that are still classified and therefore unknown to the general public, nullifying these types of questions even with a skeptic — however, these involve what might be termed "rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty" and usually there is significant supporting evidence from other sources.

Plausibility[edit]

Does belief in this theory require accepting inherently contradictory premises that the conspiring entities are incredibly competent, bone stupid, organized, clever, and hopelessly incompetent — all at the same time?

A notorious example: chemtrails. If the U.S. government wished to use chemicals to have effects at ground level, high-altitude dispersion would be the most expensively, stupidly ineffective approach imaginable (as well as readily detected by, say, spectrographs and air sampling). Furthermore, even the people running this conspiracy can't hold their breath forever, and would fall victim to it just as everyone else. So this theory would require believing in an entity (the U.S. government) that is well-resourced, competent, clever, and well-advised, while at the same time being hopelessly stupid.

Other examples are "secrets" both immensely well-kept by the most powerful and elite entities, while simultaneously being so obvious as to be easily deduced by random "bozos on the bus" who talk about them openly both on the Internet and in public (somehow without the conspirators disappearing them). Apart from chemtrails, a common example is the highly-organized and thoroughly-secret system of concentration camps operated by FEMA, which happens to come from an agency infamous for its amazingly chaotic, clumsy, and ineffective handling of Katrina. Alternatively, use any other intensely secret program that could be easily discovered and verified by anyone with a common piece of scientific equipment (or Google).

Targets of conspiracy theories[edit]

Conspiracy theories can and have been made about almost every person, group, and movement in existence, typically those with authority or prominence (real or perceived), but here are some of the ones most frequently targeted by conspiracy theorists. Articles on various targets can also be found in our category for conspiracy theorist scapegoats.

Misperception of social systems[edit]

“”Many of our lives are filled with more convenience and comfort than ever before — America is more likely to be heard singing in 12-car-deep Chick-fil-A drive-thru lines these days than at the cobbler’s table or behind the plow — yet there is great angst about our 240-year-old republic. It might be that Americans fear the institutions we built, governmental and societal, have grown too large, too out of their lane of ordained responsibility. We wonder: "Are analysts reading our text messages through the cloud? Are newsmen swilling martinis poolside with politicians, colluding over what they think the best course for the plebs might be?" Only 32 percent of Americans say they trust the media; 19 percent say they trust the federal government to do what is right. 2016’s “rigged” paranoia might be some side effect of this niggling sense that we are not quite in control, our institutions grown too sprawling to be accountable to us. All of a sudden, the comfort has a terrifying tinge to it.

|

| —538[31] |

Social systems do exhibit complex forms of order and integration which emerge from the non-intentional consequences of intentional action; these emergent orders can be mistaken for conspiracies by people who have no real concept of social structure and therefore believe that every aspect of society must be the product of someone's will. For instance, "free" capitalist markets tend to generate oligarchies or even monopolies wherever economies of scale grant competitive advantages and/or where there is a high transaction cost for consumers who switch suppliers. For an observer who naively believes that a free market always leads to a level playing field, the formation of oligopolies and total monopolies seems like an anomaly, which the conspiracy theory seeks to explain.

A variation on this is found when practices that are common in one context are not generally known to the wider public. For instance, the intelligence agencies of the US and USSR during the Cold War routinely shared information which was kept secret from the citizens of both countries. In business, certain levels of collusion among competitors, especially in oligopolistic markets, are fairly common. Such practices look conspiratorial to outsiders and may even be conspiratorial in a broad sense of the term but have little in common with the fantastic conspiracies postulated by crackpots.

A third form of this misperception occurs when conspiracy theorists assume, on the basis of ignorance and/or stereotyped thinking, that the group who is ostensibly responsible for something could not possibly have done that thing. For instance, conspiracy theories postulating that examples of ancient monumental architecture (the Egyptian or Mayan pyramids, Stonehenge, the Easter Island statues) must have been the product of aliens or whatever, usually depend on a serious underestimation of the engineering skills and technological know-how of the actual human beings on the scene.

The 9/11 attacks provide an example of all three forms of this misperception. Many powerful American individuals and institutions benefited from the attacks, including the Bush regime itself and its allies in the military-industrial complex. However, this is in no way an indication that the attacks were an American conspiracy; this is just how global geopolitics works: when something major and unexpected happens, one interest group or another will find a way to benefit from it. As Noam Chomsky has pointed out, 9/11 conspiracy theories actually get in the way of a realistic understanding of global geopolitics and the often amoral rules by which it is played.[32] Likewise, in the immediate aftermath of the attacks the Bush regime acted quickly to return to Saudi Arabia high-ranking Saudi officials and members of the Bin Laden family who were in the US at the time; this might seem conspiratorial to the average American but is consistent with standard diplomatic practice. Third, as Immanuel Wallerstein has observed,[33] 9/11 truthers under-estimate the actual organizational capacity of al-Qaida.

Overall, conspiracy theories tend to depend on the fallacious assumption that everything that happens in society must have been intended to happen by a specific agent, when in actuality many important (and also many everyday) events are the unintended or unforeseen consequences of intentional action.

What THEY don't want you to know[edit]

“”There's a similar kind of logic behind all [conspiracy theorist] groups, I think … They don't undertake to prove that their view is true [so much as to] find flaws in what the other side is saying.

|

| — Ted Goertzel, sociology professor[34][note 3] |

One of the most successful driving forces behind the spread and uptake of conspiracy theories is the entire concept that they're secret and forbidden pieces of information. This goes far beyond them being merely "juicy" (like celebrity gossip) but right to the heart of how we place value on information.

Things become valuable for their rarity, and occasionally for their utility, although a very common but highly useful thing is still cheap; contrast iron and wood for construction with gold and silver, which have useful electronic conduction properties or novel chemical applications but the price of which derives from their rarity. If it wasn't for this rarity, they would be just used rather than being held in high regard for specialist applications. The same applies to information — rarity increases value. And just as we can value useless things because they are rare, we can still value information that is rare — regardless of its truth value. This is something that has wider-reaching consequences in almost all forms of woo. Fad diets, for example, display this particular trope very well — healthy eating advice is simple, effective, and "free", but make it some "secret trick" and people will buy into it happily despite a free and effective alternative being available.

Within the realm of conspiracy theories, information is made valuable by being part of the conspiracy. "What They don't want you to know" is a phrase that is seen and heard everywhere in conspiracy land, because if information is suppressed by Them to keep it away from you, it must be secret, it must be rare, it must be valuable. It's the same force that drives people to brag about a band that only they have heard of, or say "I know something you don't", even though this defeats the purpose; nothing is cooler than knowing something someone else doesn't. The problem with conspiracies is that people mistake such hoarding value for truth value, i.e., if information has been suppressed by Them to keep it away from you, it must be true. Therefore, the trope continues to be used to add value, as well as the illusion of truth to information.

There are a few other subtle factors at play that enhance this effect. The idea of information being suppressed and withheld romanticises the idea of the conspiracy. If knowing something that others don't is a big, fat, multi-layered chocolate cake, then being the underdog and fighting against the people who want to stop you is the rich, orgasm-inducing, triple-chocolate icing cake that has your name written all over it.

A figure of hate and mistrust to direct your anger towards only enhances the experience: the Illuminati, the mainstream media — it really doesn't matter, so long as it's something to absorb additional hatred and scorn. Thus the "Them" or "They" (always capitalise it — always), reinforces the special nature of the information that the conspiracy theory purports to reveal.

The knowledge suppression aspect (for example, free energy suppression) plays nicely into our thinking about the abhorrence of censorship and the want to do something good in the world. Meanwhile, the "They" aspect plays nicely into the distrust and hatred people frequently hold for corporations, governments, or any other entity that exists in the abstract, rather than personal. It's much easier to demonise an organisation than it is to demonise a person. When a skeptic wanders into a conspiracy forum, the ad hominem responses of conspiracy advocates tend to be of the type: "you work for the Illuminati", "you're paid by Big Oil", "you're a NASA shill", or one of countless other accusations. It's never "you are the Illuminati" or "you work for David Smales, who lives at 45 9th Avenue with a wife and two children and another on the way, who plays golf on the weekend, likes his pet dog, and just happens to be the head of Big Oil". No, They are faceless and easy targets. Even in the circumstances when conspiracy theorists are capable of pointing the finger at a person they can identify outright — such as the pilot in charge of the AC-130 flying over Washington DC during the 9/11 attacks who is accused of dropping wreckage to "fake" the attack on the Pentagon — charges are always accompanied by phrases like "perhaps he didn't know what he was doing or perhaps he was following orders and wasn't aware". However, this does not apply to conspiracy theories driven by bigotry, such as racist, homophobic, or antisemitic conspiracy theories.

These factors increase the value which conspiracy theorists ascribe to information, but unfortunately for them, such clichés don't comment on the truth value of such information — in fact, they probably count against such things being true. One peculiar thing about classic conspiracy theories is how little difference they actually make in practice. Eve Sedgwick![]() puts it this way:

puts it this way:

“”Even suppose we were sure of every element of a conspiracy: that the lives of Africans and African Americans are worthless in the eyes of the United States; that gay men and drug users are held cheap where they aren't actively hated; that the military deliberately researches ways to kill noncombatants whom it sees as enemies; that people in power look calmly on the likelihood of catastrophic environmental and population changes. Supposing we were ever so sure of all those things — what would we know then that we don’t already know?

|

| —Eve Sedgwick, "You're So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You".[35]:123 |

The appeal of conspiracy theories is their suggestion of surprising explanations for what everybody already knows. The explanations do not replace the standard narratives of consensus history. Rather, they add a layer that "explains" everything as being under the control of a great and secret power. They reassure you: at least somebody's in charge, even if it's lizard people from outer space. The possibility that no one is in charge, and that the wheels of government and society got this befouled without anyone intending or controlling it, is even more frightening than any of the standard model conspiracy theories. On the other hand, if a divine plan exists (say, a Judeo-Christian one[36]), one can usefully analyze its components as part of a fairly long-running conspiracy.

Likewise, most conspiracy theories are vague on what to do about them. Suppose that the Illuminati, the Trilateral Commission, and the Lizard People are working together to pull all the strings of history, how does this translate into a plan of action to effectively resist them? Drive over to Buckingham Palace in the Mystery Machine and unmask the King of England as a lizard-person? What would that do?

For the conspiracy theorist, exposure seems to be enough; once enough people know about the conspiracy, things will just sort themselves out.

Latching onto tragedy[edit]

“”Unimpeded, conspiracy theories distort truth and erase history. They dehumanize victims. They manipulate the public.

People like [James H.] Fetzer who hide behind their computer screen and terrorize people grappling with the most unimagined grief were put on notice today. Social media companies that allow their platforms to be weaponized were put on notice today. We will continue to stand up for our rights to be free of your attempts to use our tragedy and our pain to line your pockets or gain internet "likes."

|

| —Lenny Pozner, father of Sandy Hook victim Noah Pozner[37] |

An unfortunate and sometimes callous tendency of a diehard conspiracy buff is to instantly claim that a tragedy, be it a shooting, bombing, suicide, or stubbing their toe in the morning, is in some way fabricated by or the fault of the government (or whoever the conspirators are). This is often due to confirmation bias, motivated primarily by the earnest fervor and outrage that typically dominates a conspiracy theorist's life. Sometimes, such claims are also made cynically, either for political or financial profit. Even when the initial motivation was not for profit, social media platforms have been profiting from enabling the dissemination of conspiracy theories.[38]

An even more unfortunate corollary of this is that any attempts at alternative explanations or deviations from orthodoxy are easily smeared as "conspiracy theories", and an overwhelming sentiment thus obtains where tragedies such as mass shootings, bombings, or suicides are "sacred" or "forbidden", and any discussion, whether in good faith or not, is fundamentally disrespectful. This line of reasoning is much more often used cynically by political figures to stifle discussion which could potentially reveal their incompetence, malfeasance, or general scumminess.

Denial[edit]

“”Because the war in Afghanistan is a false flag operation to distract WikiLeaks with hundreds of thousands of pages of documents to go through.

|

Denial is strongly linked with conspiracies in two senses. In one, the conspiracy theorist is in denial of the "official story," which is more often than not the one supported by facts. However, in the second sense, anyone denying the existence of a conspiracy inadvertently further convinces the conspiracy theorist of its existence. Denial of ongoing conspiracies can be taken as proof that the employees are "in" on whatever conspiracy they are busily denying.

Usually, the more they deny, the more conspiracy theorists will take it as proof — because, well, "They would say that, wouldn't they?".

Furthermore, if people do not deny the theory, this can also be taken as proof of a conspiracy on the grounds that "It has never been denied." This applies equally to anyone involved in a large enterprise, such as "scientists," "the Army," "automobile manufacturers," "Big Science/Petroleum/Tobacco/Florists" etc. The fact that this entire line of reasoning is circular hardly needs to be pointed out.

No agreement? No problem![edit]

Conspiracy theorists bear a striking resemblance to religious denominations, in that it is literally impossible to get them to all agree on all the same details of said conspiracy. Even finding two that totally agree is a serious challenge. But thankfully, there's an incredibly easy and convenient way out of this.

For example, say you believe that no planes hit the towers on 9/11, and that instead, millions of witnesses in NYC are all lying and hence also part of this enormous cover-up the planes were CGI and added in later to LIVE news feed. In this case, what do you do about people like Alex Jones, who, despite believing 9/11 was an inside job, rejects the no plane theory? Isn't it annoying that even someone like him doesn't agree with you?

No problem! Just declare (no evidence required) that people like Jones along with all the others who don't share your views are actually in on the conspiracy and were planted to prevent the public from seeing the REAL truth.[39] Checkmate!

But then again, with many conspiracy theorists claiming that pretty much everyone other than themselves are in on the conspiracy, they pretty much all cancel each other out anyway. Oof.

As a logical fallacy[edit]

Canceling hypothesis[edit]

This is when a lack of evidence for a given hypothesis is explained away by the ad hoc introduction of a second hypothesis, which directly contradicts the original claim. This is especially popular among denialists and conspiracy theorists (especially flat earthers and anti-vaxxers).

- P1: Hypothesis X is true.

- P2: Hypothesis X lacks evidence, or is presented with contradictory evidence.

- C: Therefore, Hypothesis Y is true (which cancels out Hypothesis X).

Self-sealer[edit]

A self-sealer is an unfalsifiable argument that is framed in such a way that any evidence brought against it can be dismissed by simply alleging it to be part of a larger cover-up.

Here, the argument for their conclusion depends on their conclusion already being accepted as true. It isn't too difficult to see why this is not a very compelling argument, and is only convincing to people who already agree with you.

- P1: X is true.

- P2: X lacks evidence, or is presented with contradictory evidence.

- P3: A lack of evidence or a presence of evidence to the contrary means that X is being covered up in some way.

C: Therefore, X is true.

Slippery slope[edit]

One common theme in conspiracy theories is that if one conspiracy theory is real, then all the others must be as well. If 9/11 was an inside job, then the Illuminati must be real. If Michael Jackson/Tupac/(Insert Celeb here) is alive, then NASA is concealing evidence of intelligent extraterrestrials.

This is not correct. If later evidence does show 9/11 to be an inside job (very unlikely, although technically possible),[note 4] it doesn't follow that Sandy Hook was a false flag operation.

There are, however, groups of conspiracy theorists who mash together every conspiracy theory you could think of into one big one. Every tragedy was caused to distract from the real problems. War was caused to further the plans (or two Illuminati bloodlines wanted to duke it out), a world event was staged to distract us, and a celebrity death was designed to hide their whistleblowing along with every secret society being created to further their plans.

The conspiracy mentality[edit]

“”Conspiracy theories are dangerous for many reasons. Among other things, they provide a way to reduce mental distress by changing our perception of a problem without actually doing anything to solve the problem. They're the mental equivalent of a pacifier.

|

| —Caroline Orr[40] |

Daniel Pipes, in an early essay "adapted from a study prepared for the CIA", attempted to define which beliefs distinguish 'the conspiracy mentality' from 'more conventional patterns of thought'. He defined them as: appearances deceive; conspiracies drive history; nothing is haphazard; the enemy always gains power,![]() fame, money, and sex.[41] The Enemy, whoever they are, is always winning or on the brink of winning, lending urgency and a sense of mission to theories that otherwise wouldn't be very exciting.

fame, money, and sex.[41] The Enemy, whoever they are, is always winning or on the brink of winning, lending urgency and a sense of mission to theories that otherwise wouldn't be very exciting.

Evidence suggests that conspiracist-minded people tend to think that they are both "too special to be duped" and that they desire "uniqueness" provided by belief in conspiracy theories.[42] Conspiracy theories can make people with boring, insignificant lives feel like they really matter, and people who have no accomplishments to set them apart from anyone else can feel like they've become a part of something that counts. Simply put, people tend to buy into this stuff if they're the type that feels the need to. Conspiracy theorists are not necessarily mediocrities or losers, but a lot of them are. People who are truly exceptional, successful, and accomplished probably don't even have time for this kind of stuff, let alone any inclination towards it.

The mentality that drives and breeds conspiracy theories is one of total, eternal paranoia. Someone (most popularly The Government) is out there, controlling everything, hiding this, lying about that, working to unfold some vast plan involving tens of thousands of people working in flawless unison. Which government do they mean? Doesn't matter. Usually it's at the multinational level, with the United Nations and European Union being popular targets. It could just as easily be any other multinational entity, any national government, any regional government, or even all governments, everywhere, at the same time. Conspiracy theorists may not even know themselves which government they're talking about, because The Government is a vast, omniscient octopus, you see. They are simultaneously everywhere and nowhere, perpetually on the brink of completing schemes that will ensure total control, yet somehow never quite getting there.

Psychology of conspiracy theorists[edit]

Psychological research on conspiracy theories is still a young field, having only started in the mid-1990s.[43] A meta-analysis of 96 studies of conspiracy theorists with the Big Five personality traits![]() (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism) found no correlation between conspiracy theorists and any of the Big Five traits.[43] There may be some overlap between conspiracy theorists (possibly as high as 50% of Americans[44]) and people with delusional disorder (estimated at 0.2% of the total population), but clearly something else would have to explain it because delusional disorder is too rare.[45] An important difference between people who believe in conspiracy theories who do not have delusional disorder and those who do is that people without delusional disorder are not necessarily fully convinced of the theory, whereas people with delusional disorder cannot be convinced otherwise.[45] There is currently no consensus as to what psychological traits may cause people to believe in conspiracy theories.

(openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism) found no correlation between conspiracy theorists and any of the Big Five traits.[43] There may be some overlap between conspiracy theorists (possibly as high as 50% of Americans[44]) and people with delusional disorder (estimated at 0.2% of the total population), but clearly something else would have to explain it because delusional disorder is too rare.[45] An important difference between people who believe in conspiracy theories who do not have delusional disorder and those who do is that people without delusional disorder are not necessarily fully convinced of the theory, whereas people with delusional disorder cannot be convinced otherwise.[45] There is currently no consensus as to what psychological traits may cause people to believe in conspiracy theories.

Defence of conspiracy theories[edit]

While conspiracy theories often show little regard for evidence or plausibility, and may incorporate racist or other unacceptable mindsets, there is a minority current of opinion that says the label "conspiracy theory" is used by those in power to stifle legitimate criticism and to smear opponents. Anthropologist Erica Lagalisse has suggested that the label, together with the stereotype of the conspiracy theorist as an uneducated basement dweller, manifests a form of class discrimination with privileged wealthy elites attacking poor (and hence basement-dwelling) people whose conspiracy theories typically represent in a confused way the real forces controlling their lives. Lagalisse has suggested that automatically condemning and mocking those who come up with conspiracy theories is an example of how those in positions of power systematically marginalize and delegitimize criticism from outside the establishment.[46]

It has also been suggested by some historians that the CIA promoted the concept of the paranoid conspiracy theory mindset to discredit genuine criticisms of real conspiratorial behavior by the US government, although these claims have been criticized, while the assertion that the agency invented the term "conspiracy theory" has been debunked (it dates back to at least 1863).[47] Political scientist Lance deHaven-Smith has argued in his book, Conspiracy Theory in America, that in the 1960s, with growing suspicion about the government's potential involvement in the John F. Kennedy assassination and other events, CIA field offices were tasked with a public relations campaign to ridicule critics as irrational conspiracy theorists, promoting the impression that anyone suggesting secret government conspiracies was crazy.[48] While a CIA memo entitled Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report was uncovered in 1976, "there is not a single sentence in the document that indicates the CIA intended to weaponise, let alone introduce the term “conspiracy theory” to disqualify criticism. […] The authors of the document deploy the term in a very casual manner and obviously do not feel the need to define it. This indicates that it was not a new term but already widely used at the time to describe alternative accounts. At no time do the authors recommend using the label “conspiracy theory” to stigmatise alternative explanations of Kennedy’s assassination. This suggests that the term had not yet acquired the same level of negativity it possesses today."[49] According to American Literary and Cultural History Professor Michael Butter, "[t]here is no indicator that the CIA memo had any impact on the popularity of the concept [of conspiracy theories]. Indeed, the casual way the memo uses the phrase just once implies that the concept was already quite popular in the 1960s."[50]

DeHaven-Smith has argued that the appropriate response to conspiracy theories is not to crack down on them or decry the thought processes that seek hidden explanations, but to ensure that suspicious events are investigated in a transparent, independent, and objective way.[48][51] However, this sort of logic has its limits, since some conspiracy theories are unfalsifiable and predicated on simple belief, while others are based on disregarding contrary evidence and ignoring alternative explanations; there's a reason that conspiracy theories have been described as "quasi-religious".[52]

Further evidence which is cited to argue that there was a concerted attempt to stigmatise conspiracy theorists can be seen in the contrasting fortunes of Charles A. Beard,![]() a once-hugely influential historian who sought to explain American history through economic self-interest of elites but fell out of favor during the Cold War, and one of his chief critics, Richard Hofstadter, who popularised attacks on the "paranoid style" of conspiracy theorising and became one of the most prominent public intellectuals in the 1960s.[53] What name could be more perfect for a crazy conspiracy theorist than Beard, unless it was Neck-Beard?

a once-hugely influential historian who sought to explain American history through economic self-interest of elites but fell out of favor during the Cold War, and one of his chief critics, Richard Hofstadter, who popularised attacks on the "paranoid style" of conspiracy theorising and became one of the most prominent public intellectuals in the 1960s.[53] What name could be more perfect for a crazy conspiracy theorist than Beard, unless it was Neck-Beard?

As a snarl word[edit]

"Conspiracy theory" can also be used as a snarl word to dismiss a valid worry that a group is up to something. A good example would be the discovery of COINTELPRO. People such as the Black Panthers and Abbie Hoffman suspected that the FBI had a covert program dedicated to tracking, discrediting, and destroying them; however, they were largely written off as paranoid radicals finding a way to blame the man for their failures. Then, lo and behold, in 1971 the "FBI Burglars" released documents mentioning COINTELPRO. This in turn led journalists to investigate and expose the program, proving that their fears were in-fact correct.[54]

Skeptics must always seek out the truth, even if it does very occasionally end up proving those "nutjobs" right. Considering the sheer number of conspiracy theories, it's almost certain that one or two of them might be right. However, this by no means says that they are generally valid. Once a conspiracy theory has been proven, it ceases to be a conspiracy theory and just becomes a conspiracy.

Remember, you're not paranoid if They really are out to get you.

History of conspiracy theorists[edit]

Theorising about secret forces controlling your life is as old as humanity, going back to include most forms of religion and superstition. We can certainly see large numbers of conspiracies, both real and imagined, through history, with the European wars of religion in the 16th and 17th century perhaps a highpoint. James II![]() was surrounded by theories that he was secretly a Roman Catholic and planned to forcibly convert the nation, while Elizabeth I instituted a police state to counter a variety of alleged Catholic conspiracies, some of which (such as the Throckmorton Plot

was surrounded by theories that he was secretly a Roman Catholic and planned to forcibly convert the nation, while Elizabeth I instituted a police state to counter a variety of alleged Catholic conspiracies, some of which (such as the Throckmorton Plot![]() of 1583) were at best inept.

of 1583) were at best inept.

The modern concept of a conspiracy theory seems to require a few specific elements: mass media, and large scale social and political systems, and the rise of both accentuated the phenomenon. Discussion of "conspiracy theories", using that phrase, goes back to the later 19th century, with the 1881 assassination of James Garfield promoting a major increase.[55]

Karl Popper's The Open Society and Its Enemies popularised the concept in 1945. As part of a defence of liberal society and the invisible hand of the market, and an attack on totalizing theories of history such as Marxism, he ridiculed "the conspiracy theory of society". He defined this as akin to a religious belief that seeks to explain everything by conspiracy:

It is the view that an explanation of a social phenomenon consists in the discovery of the men or groups who are interested in the occurrence of this phenomenon (sometimes it is a hidden interest which has first to be revealed) and who have planned and conspired to bring it about.

He later set it out in an even more reductive way, as the view that all events in society "are the results of direct design by some powerful individuals or groups" (Conjectures and Refutations). Yet this does not describe most actual conspiracy theories, which leave space for chance and accident, and often seek to combine talk of conspirators with the identification of wider forces (e.g. capitalism) which drive them. Indeed Charles Pidgen has claimed that this is a caricature which no conspiracy theorist actually believes.[56]

Following Popper, the 1960s saw the development of the modern conspiracy theory, which was clearly influenced by John F. Kennedy's assassination, and at the same time modern attacks on conspiracy theorising such as Richard Hofstadter's The Paranoid Style in American Politics.

Real conspiracies[edit]

Real conspiracies have existed to operate without their frustration until the deed is completed. Two very different conspiracies operating almost simultaneously in the same country were the Holocaust, a secretive plot to exterminate Jews that required careful concealment of the mass-murder to prevent resistance even by the victims, and the July 20 plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler. The first involved the leadership of the Nazi Party, law enforcement, official media, commercial interests, the Armed Forces, and above all the elite paramilitary of the Nazi Party. The totalitarian system could steal anything, arrest anyone, and move anyone about without consent, and all in nearly-complete secrecy. Relatively few people in the German Establishment got indications of massacres and deportations, and finally mass-killings in the concentration camps: senior military officers, diplomats, intelligence agents, and retired political figures who, as one could predict, might find such so objectionable that they tried to overthrow the regime committing the Holocaust. The July 20 plot, had it succeeded, would have led to a very different set of events in the European Theater of War beginning with the death of Hitler and the overthrow of the Nazi regime. Both the Holocaust and the July 20 plots were genuine conspiracies well documented after the fact.

Instead of Nazi Germany, one can also mention Russia or Ancient Rome — any imperialistic dictatorship without democratic transparency and accountability — as examples of places where conspiracies do thrive and are abundantly documented by historians. (In fact, in places like Russia, it is liberal intellectuals who are casual conspiracy theorists, stigmatizing people who trust the government — and, unfortunately, they are usually right!) One notable example of such a conspiracy theory with explicit rationalistic overtones (which even got praised in the prestigious journal "Nature") is that the resurrection of Jesus was staged by the Romans, which, for once, is at least certainly more rational in comparison than the official version of the events — that a provincial Jewish carpenter resurrected from the dead and flew up into the sky to sit on a throne in Heaven!

Similar conspiracies have indeed rarely happened, such as Zersetzung![]() and the CIA using a doppelganger of Indonesian president Sukarno

and the CIA using a doppelganger of Indonesian president Sukarno![]() to produce a pornographic movie in an attempt to make him less popular.[57][58]

to produce a pornographic movie in an attempt to make him less popular.[57][58]

See also[edit]

| For those of you in the mood, RationalWiki has a fun article about Conspiracy theories. |

Conspiracies abound[edit]

Conspiracy theory peddlers[edit]

Not so notable conspiracy theorists[edit]

Want to read this in another language?

External links[edit]

General[edit]

- Centre for Conspiracy Culture at the University of Winchester

- The Conspiracy Skeptic podcast

- Why I go after the grand conspiracy theorists

- Lies, damn lies, and "counter-knowledge", Daily Telegraph

- Katel, Peter. "Conspiracy theories: Do they threaten democracy? CQ Researcher 23 Oct. 2009, vol. 19, no. 37

- Are conspiracy theories destroying democracy?

- Why grand conspiracy thinking is a threat to science and medicine

- Flowchart guide to the grand conspiracy

- And another

- An even more absurd (and non-Poe) example

- 7 Insane Conspiracies That Actually Happened

- Jade Helm ends with no takeover -- and these 6 nutters hope you forget their idiotic fear mongering

- “Two million dead on the side of the patriots”: How Alex Jones’s “Jade Helm” conspiracy theory got very dangerous very fast

- The Conspiracy Theory Handbook: explains why conspiracy theories are so popular, how to identify the traits of conspiratorial thinking, and what are effective response strategies

- Why People Fall For Conspiracy Theories

- Conspiracy: Theory and Practice: Toward a Taxonomy of Conspiracies Edward Snowden, 2021

- A Case Study

- A chart demonstrating the rarity of conspiracy theories being confirmed

How to talk to conspiracy theorists[edit]

- How to talk to conspiracy theorists—and still be kind by Tanya Basu

- How I talk to the victims of conspiracy theories by Marianna Spring

- I've been talking to conspiracy theorists for 20 years – here are my six rules of engagement by Jovan Byford

- How to Talk to Friends and Family Who Share Conspiracy Theories by Charlie Warzel

- Tips For Talking To The Conspiracy Theorist In Your Life by Maggie Mullen

- How to Rescue Someone From a Conspiracy Theory by Charles Duhigg

- How To Talk With—And Maybe Help—Someone Who Believes In QAnon And Other Conspiracy Theories by Lisette Voytko

Bibliography[edit]

- Knight, Peter (2003). Conspiracy theories in American history: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-812-9.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ The Rough Guide to Conspiracy Theories is notably credulous, without much debunking.[27]

- ↑ Or at least just over-represented on the internet due to sites like YouTube.

- ↑ Also a good description of certain other nutjobs we know…

- ↑ That's how the scientific method works.

References[edit]

- ↑ Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia by John Gray (2007) Farrar Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374105987.

- ↑ 20th Century Words by John Ayto (1999) Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198602308.

- ↑ "Conspiracy Theories and the Conventional Wisdom" by Charles R. Pigden (2007) Episteme: A Journal of Social Epistemology 4(2):219-222. doi:10.1353/epi.2007.0017.

- ↑ Conspiracy Theories: The Philosophical Debate by David Coady (2019) Routledge. ISBN 113824791X.

- ↑ Interpreting Conflict: Israeli-Palestinian Negotiations at Camp David II and Beyond by Oded Balaban (2005) Peter Lang. ISBN 0820474509.

- ↑ How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them by Jason Stanley (2018) Random House. ISBN 9780525511830.

- ↑ Trump: Let Them Eat Conspiracy Theory by John Hickman (Nov 13, 2016) Like the Dew (archived from December 12, 2015).

- ↑ "Bad Moon Rising," The West Wing (2001) Season 2, Episode 19.

- ↑ Conspiracy Theories & Secret Societies For Dummies by Christopher Hodapp & Alice Von Kannon (2008) Wiley Publishing. ISBN 0470184086.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Of Conspiracy Theories by Brian L. Keeley (1999) The Journal of Philosophy 96(3):109-126.

- ↑ Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia by Peter Knight (2003) ABC-CLIO. Volume 1. ISBN 1576078124.

- ↑ Conspiracy Panics: Political Rationality and Popular Culture by Jack Z. Bratich (2008) State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791473333.

- ↑ Conspiracy theory logical fallacies (updated 27.05.2012).

- ↑ Nichols, Tom. The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. p. 58.

- ↑ Shallow Dives (Web Exclusive): Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) (Jul 5, 2015) YouTube.

- ↑ The Unmaking of Adolf Hitler by Eugene Davidson (2004) University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826215297.

- ↑ The Persistence of Conspiracy Theories by Kate Zernike (April 30, 2011) The New York Times.

- ↑ The Age of Anxiety: Conspiracy Theory and the Human Sciences, edited by Jane Parish & Martin Parker (2001) Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631231684.

- ↑ Deep Throat’s identity was a mystery for decades because no one believed this woman by Gillian Brockell (September 27, 2019 at 7:06 p.m.) The Washington Post.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 On the Viability of Conspiratorial Beliefs by David Robert Grimes (2016) PLoS ONE 11(1):e0147905. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147905.

- ↑ A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America by Michael Barkun (2003) University of California Press. ISBN 0520238052.

- ↑ A Culture of Conspiracy: Mr. Barkun talked via video link from Syracuse, New York, about conspiracy theories. Among the subjects addressed were subcultures, the Illuminati, Skull and Bones, and a New World Order. Mr. Barkun also talked about the origins of and belief in conspiracy theories, and responded to audience telephone calls, faxes, and electronic mail (March 12, 2004) C-Span.

- ↑ Introduction to the Q-web by Dylan Louis Monroe (archived from 31 Jan 2019 03:49:10 UTC). A diagram of what a super-conspiracy theory looks like, QAnon in this case.

- ↑ Escaping the Rabbit Hole: How to Debunk Conspiracy Theories Using Facts, Logic, and Respect by Mick West (2018) Skyhorse. ISBN 1510735801.

- ↑ The Conspiracy Theory Spectrum (Feb 5, 2019) Metabunk.

- ↑ Michael Kelly: The Road to Paranoia by Michael Kelly (June 19, 1995) The New Yorker.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 The Rough Guide to Conspiracy Theories by James McConnachie & Robin Tudge (2013) Rough Guides. ISBN 9781409362456.

- ↑ Poor Richard's Almanack (1735) by Benjamin Franklin.

- ↑ Moon Landings Faked? Filmmaker Says Not! by S G Collins (Jan 29, 2013) YouTube.

- ↑ The JFK 100: "Why?" JFK Online: JFK Assassination Resources Online.

- ↑ One North Carolina County Shows The Cracks In The GOP’s Defenses by Clare Malone (Oct. 27, 2016) FiveThirtyEight.

- ↑ 9-11: Was There an Alternative? by Noam Chomsky (2011) Seven Stories Press. Revised edition. ISBN 1609803434.

- ↑ Does Al-Qaeda Still Matter? by Immanuel Wallerstein (3/3/15) Fernand Braudel Center, Binghamton University.

- ↑ Vocal Minority Insists It Was All Smoke and Mirrors by John Schwartz (July 13, 2009) The New York Times.

- ↑ Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (2003) Duke University Press. ISBN 0822330156.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on God's Plan.

- ↑ Lenny Pozner’s Official Statement After Defamation Victory HONR Network (archived from July 9, 2019).

- ↑ First, they lost their children. Then the conspiracy theories started. Now, the parents of Newtown are fighting back. by Susan Svrluga (July 8, 2019 at 4:57 PM) The Washington Post.

- ↑ Alex Jones and the Genesis Radio Network of 118 AM are FRAUDS!!! by Zachary K. Hubbard (June 24, 2014) free to find truth .

- ↑ Conspiracy theories are dangerous for many reasons. Among other things, they provide a way to reduce mental distress by changing our perception of a problem without actually doing anything to solve the problem. They're the mental equivalent of a pacifier. 1/ by Caroline Orr (2:34 PM - 31 Mar 2018) Twitter (archived from April 1, 2018).

- ↑ Dealing with Middle Eastern Conspiracy Theories by Daniel Pipes (Winter, 1992) Orbis.

- ↑ Too special to be duped: Need for uniqueness motivates conspiracy beliefs by Roland Imhoff & Pia Lamberty (2016) European Journal of Social Psychology 47(6):724-734. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2265.}}

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Psychological Research on Conspiracy Beliefs: Field Characteristics, Measurement Instruments, and Associations With Personality Traits by Andreas Goreis & Martin Voracek (11 February 2019) Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00205.

- ↑ 12 Million Americans Believe Lizard People Run Our Country: About 90 million Americans believe aliens exist. Some 66 million of us think aliens landed at Roswell in 1948. These are the things you learn when there's a lull in political news and pollsters get to ask whatever questions they want. by Philip Bump (April 2, 2013) The Atlantic.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Are Conspiracy Theories Delusional? A brief checklist for distinguishing between conspiracy theories and delusions. by Shauna Bowes (Dec 02, 2020) Psychology Today.

- ↑ Occult Features of Anarchism: With Attention to the Conspiracy of Kings and the Conspiracy of the Peoples by Erica Lagalisse (2019) PM Press. ISBN 1629635790.

- ↑ English Insincerity on the Slavery Question by C. A. Bristed (11 Jan 1863) The New York Times via Newspapers. First use of "conspiracy theory" by Charles Astor Bristed.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Conspiracy Theory in America by Lance deHaven-Smith & Matthew T. Witt (2014) University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292757697.

- ↑ There’s a conspiracy theory that the CIA invented the term ‘conspiracy theory’ – here’s why by Michael Butter (March 16, 2020 11.24am EDT) The Conversation.

- ↑ Tinfoil hats not needed to repel CIA ‘conspiracy theorist’ creation claim (January 31, 2022) Australian Associated Press.

- ↑ Conspiracy Theory Reconsidered: Responding to Mass Suspicions of Political Criminality in High Office by Lance deHaven-Smith (2013) Administration & Society 45(3):267-295. doi:10.1177/0095399712459727.

- ↑ Conspiracy theories as quasi-religious mentality: an integrated account from cognitive science, social representations theory, and frame theory by Bradley Franks et al. (16 July 2013) Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00424.

- ↑ The Paranoid Style in American Politics by Richard Hofstadter (1965) Vintage Books.

- ↑ Burglars Who Took On F.B.I. Abandon Shadows by Mark Mazzetti (January 7, 2014) The New York Times.

- ↑ "Conspiracy Theory: The Nineteenth-Century Prehistory of a Twentieth-Century Concept", Andrew McKenzie-McHarg (2018) In Conspiracy Theories and the People Who Believe Them, edited by Joseph E. Uscinski. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0190844086.

- ↑ Popper Revisited, or What Is Wrong With Conspiracy Theories? by Charles Pigden (1995) Philosophy of the Social Sciences 25(1):3-34. doi:10.1177/004839319502500101.

- ↑ NYT reports CIA conspired to topple Sukarno in Indonesia. The Financial Express, 26 May 1998

- ↑ Indonesia and CIA Pronography. Secrecy News, fas.org, 24 July 2001.

KSF

KSF