English spelling reform

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 24 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 24 min

| We control what you think with Language |

| Said and done |

| Jargon, buzzwords, slogans |

“”If u cn rd ths, u cn bcm a sec & gt a gd jb.

|

| —Anon, 1960s era ad copy for a mail order secretarial school. |

English spelling reform is a perennial favorite subject for the more harmless variety of cranks. Many proposals to change English spellings have been ventured from the 16th century to the present. However, none of them have made significant headway.

The only one with any traction is the very slight reform by Noah Webster.![]() His reform added to the lovely chaos by introducing an artificial distinction between written British English and American English, while keeping most of the traditional irregularities in place.

His reform added to the lovely chaos by introducing an artificial distinction between written British English and American English, while keeping most of the traditional irregularities in place.

The chaos that is English spelling[edit]

| Without silent e | With silent e | IPA transcription |

|---|---|---|

| slăt | slātɇ | /slæt/ → /sleɪt/ |

| mĕt | mētɇ | /mɛt/ → /miːt/ |

| grĭp | grīpɇ | /ɡrɪp/ → /ɡraɪp/ |

| cŏd | cōdɇ | /kɒd/ → /koʊd/ |

| cŭt | cūtɇ | /kʌt/ → /kjuːt/ |

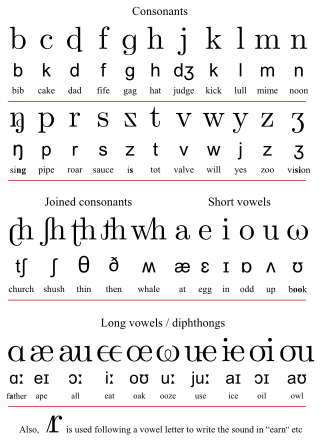

English, like many other languages with a long literary tradition, has a "deep" spelling; it has fallen largely away from the ideal alphabetic principle in which there is a close correspondence between individual characters of the script and specific sounds in the language (a "shallow" orthography). English is written with a twenty-six letter version of the Latin alphabet. No diacritical marks are used in any words of the core vocabulary. But English has from twenty-four to twenty-six consonants,[note 1] and, depending on dialect, anywhere from fourteen to twenty-one separate vowel sounds, including diphthongs that English treats as simple vowels.[1] A twenty-six letter alphabet does not begin to cover this.[note 2][note 3]

English copes with its alphabetic inadequacy by a number of stratagems. English uses many digraphs such as sh, ch, ng, and th, two-letter combinations that represent a single sound. But the most basic stratagem used in English spelling, as you learned on Sesame Street, is onset and rhyme. In native words, the sounds of onsets can usually be deduced from the written form; English spelling only tolerates silent letters in syllable onsets for non-native words (rhythm, science) or clusters that are no longer possible (knife, gnome). The complexities of English spelling are mostly in the rhymes and part-rhymes ("rimes"). Readers of English learn that the closing letters of sing and bring have one value, but that the same characters must be realized differently in singe and fringe. There are moreover often several variants that can be used to spell these rhymes; many, such as this example, make use of a silent E; but alternatives exist for most silent-E spellings. The rhymes also serve to distinguish homophones and indicate word origins, factors that have nothing to do with how the word is usually pronounced.[2]

Perceived inadequacies in this system — it's easy to compile examples (tongue, fondue) where the system seems obviously broken[note 4] — are generally the impetus behind proposals to reform English spelling.[3][note 5] Other languages have undergone — sometimes significant — spelling reforms in modern times. German has even had two in the span of a century (in 1901 and 1998, respectively). Part of the problem with English spelling reform — as evidenced by the effects of the Websterian attempt — is that it would be almost impossible to get acceptance from all English-speaking countries for a reform.

History of the current chaos[edit]

English was fortunate that its standard orthography was framed in the 15th and 16th century by the Tudor chancery, and fixed in semi-permanent form when William Caxton set up a printing press and began printing books in London. Spellings were free, though a consensus was shaping, and not fixed into a canonical form until the appearance of Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of 1755, but the general rules of the system were put in place at that time. During this time, English was enduring a sweeping sound shift involving its vowel sounds, a process known as the Great Vowel Shift![]() . As a result,

. As a result,

- the values of vowel letters in English do not resemble the sounds they represent in Latin, Italian, or the other more phonemically spelled Romance languages; and

- English spelling embodies a late Middle English phonology, one in which most words would be pronounced with values much closer to their standard values elsewhere, but which no one would understand easily if spoken aloud today.[4]

The vowel shift gave current English "long vowels" values that differ markedly from the "short vowels" that they relate to in writing. Since English has a literary tradition that goes back into the Middle English period, written English continues to use Middle English writing conventions to mark distinctions that had been reordered by the chain shift of the long vowels.

A system with multiple layers[edit]

Contributing to the chaos is English's willingness to absorb words from other languages, a process that once again goes back to the Middle English period, where much of the Germanic core vocabulary were dropped in favor of Norman French words. The processes of word borrowing, and new coinages from learned classical roots, have continued through the present. When English borrows a word from a language with a alphabetic script, it usually borrows the spelling as well, while stripping away any unfamiliar diacritical marks.[5] The loss of diacritics may of course cause the words to become nonsensical (or worse yet, change meaning) when viewed through the eyes of a foreigner, but most English speakers don't care. (Feliz ano nuevo, everybody!) Since there's no single system for the native words, why should there be with these?

As a result, English spelling contains multiple levels, tiers, or subgroupings in its lexicon. A literate English speaker can usually make a fairly good guess about how a word will be pronounced from its spelling, but only if they can assign it to the correct group. These tiers include:[note 6]

- The core Anglo-Saxon vocabulary: the most basic and native layer of English: make, do, have, be, love, fish, heart, stool, throw. The long history, familiarity, and frequency of appearance of many of these words means that many silent letters and ambiguities are tolerated here: to, too, two; light, through, cough. Mixed in with these are a handful of Old Norse loanwords, primarily pronouns beginning with th- such as "they", "them", and "their", which displaced native and fairly similar Anglo-Saxon pronouns that began with h.[5]

- Early borrowings from Norman French. There are too many of these to be considered outside the core lexicon: table, chair, court, pork, grain, soup, river, please. The rules for spelling and pronouncing these core level words are similar to the rules for the core Germanic words, but there are differences; compare Germanic gilt, soul with Norman gist, soup. [5]

- Foreign words that still carry a whiff of exoticism about them. Most of these have been borrowed from a wide variety of languages using the Latin alphabet in their native forms, giving rise to a series of one-offs: pizza, lasso, czar, gneiss, kraal, coyote, aardvark, kindergarten. Of these foreign words, two subgroups are large enough to be considered separate levels in themselves:

- Learned words formed from Latin and Greek roots. Greek, especially, has many consonant clusters that do not appear in English. The usual response is to just leave the uncomfortable sounds out: pneumonia, psychedelic, xeric, diphthong. This group of words is more likely than the others to be encountered first in writing rather than in speech. Latin words also shift their accented syllable in their inflections. This carries over and turns into a productive feature in English: noun CONtract, "a formal agreement", vs. verb conTRACT, "shrink", also "make a formal agreement" (the word "protest" is a bit of an oddity in this regard, as PROtest stressed on the first syllable can be either a verb or a noun) These words change their stressed syllable as prefixes and suffixes are added as well. These accent changes also affect the way the written vowels are realized, with stressed syllables receiving full pronunciation, and unstressed syllables being reduced: PHOtograph, phoTOGraphy, photoGRAPHic.[5]

- More recent borrowings from French: lingerie, garage, cabernet, taupe, ingenue. There are enough of these that they tend to become a default value for unfamiliar foreign words; when English speakers see the name of the late Chilean dictator Pinochet, they are drawn to a Frenchified pee-no-shay rather than the correctly Spanish pee-no-chet.[5] [note 7]

Reasons for proposing reforms[edit]

English spelling, therefore, is a haphazard collection of inconsistencies assembled by history without plan or purpose. It has in fact adopted some spellings on pure caprice; the spurious 'b' in "debt" and "doubt" was inserted in memory of Latin debitum and dubitum, without regard to the fact that the words had been passed through French without either the sound or the letter. "Island" likely owes its irregular spelling to a false etymology connecting it with Norman French "isle". Reformers point out that these irregularities convey no information or nuance, and that tradition is the only reason for retaining them.

Possible link with dyslexia[edit]

There is in fact evidence that the difficulty of English spelling contributes to dyslexia. Some researchers have claimed that languages with deep, non-phonemic spelling systems like English and French contribute to dyslexia. In these languages, readers in general have a harder time learning to decode new words than in languages with shallow spelling systems, such as German. Other researchers, by contrast, have found that dyslexics struggle to decode written language regardless of the depth or regularity of the spelling system.

Languages like German and Italian moreover keep their spelling system relatively shallow by a strong prescriptive tradition and official grammar; rather than writing being anchored to speech, the highest social status speech is anchored to the written forms. For many speakers, the written standard doesn't much resemble the speech people actually use in daily life.[note 8] German is unique in another way in that it capitalizes nouns, which some studies suggest aids in reading comprehension. English did the same (on a case by case basis) in the 18th century, as can be viewed in the United States Constitution. Interestingly, some pseudolaw claims hinge on some capitalization or other.

Additional research needs to be done about the effects that partially logographic scripts (such as those of China and Japan) and semi-syllabic scripts (like those that prevail on the Indian subcontinent) have on the acquisition of written language.[6][7]

Spelling is hard[edit]

Other reasons advanced for spelling reform would remove the "drudgery" and memorization involved in learning English spelling. One must concede this is a valid point. Some believe that complex spelling inhibits children's ability to write. It gives cause for self-consciousness; writers will choose only those words they know how to spell, and as such their spoken vocabulary may be broader than the words they choose to write. Or vice versa: a written word is a part of their working vocabulary, but they hesitate to speak it aloud, having no idea how to say it. The English Spelling Society believes that the system of English spelling encourages illiteracy, and as such decreases social capital![]() .[8][9]

.[8][9]

To purge corruption[edit]

The lack of system and planning manifested by traditional spellings just seems to be an esthetic nuisance for some people. The English Spelling Society considers traditional English spelling to be a "corruption" that diverges from the purity of the "alphabetic principle" that "(t)he letters of the alphabet were designed to represent speech sounds." It needs to be updated, apparently because it hasn't been. "Unlike other languages, English has not systematically modernized its spelling over the past 1,000 years, and today it only haphazardly observes the alphabetic principle."[10]

World peace[edit]

Others, however, have grander ideas about what English spelling reform will in fact achieve, apart from making English possibly easier to spell. Andrew Carnegie thought that spelling reform might lead to world peace under the dominion of English as a universal language. "What could be a more effective agency than that all men should communicate with each other in the same language, especially if that language were English?" It became his hope that English would become universal, "the most potent of all instruments for drawing the race together, insuring peace and advancing civilization," an agenda that sounds somewhat imperialistic and Anglocentric to contemporary people. Carnegie thought that English spelling was the chief obstacle to this dream: "(t)he foreigner has the greatest difficulty in acquiring it because of its spelling."[11]

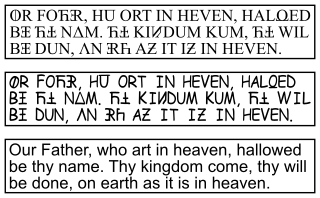

Jaber George Jabbour, a Syrian banker living in the UK, similarly proposed his own phonetic alphabet called SaypYu (dhɘ kwik brawn foks jɘmpt owvɘr dhɘ leyzi dog), and believes that such an alphabet would end misunderstandings and foster world peace.[12]

However, the Bahá'í Faith, which holds that an international auxiliary language would in fact foster world peace, rejects a respelled version of English as such a language. Not only is English identified with certain world powers, but English spelling reform simply has too slight a chance to succeed to be worth pursuing.[13]

Think of the savings![edit]

Others suggest that we could save money by changing English spelling. In a 1905 editorial, the Saturday Evening Post, not content with suggesting that world peace would result from spelling reform, estimated that 10% of the letters in written English were superfluous. Getting rid of them would be just like money in the bank. "The unnecessary letters in English are around ten percent — all deadheads in the communication of ideas." Their removal would save time and money in printing and writing, a "matter of untold millions."[14] This point has become even more pertinent with the rise of personal computers,![]() digitization,

digitization,![]() the service economy,

the service economy,![]() and a move to a knowledge economy,

and a move to a knowledge economy,![]() whereby most innovation, communication, as well as recreational activities involve typing on a computer.

whereby most innovation, communication, as well as recreational activities involve typing on a computer.

A partially successful reform[edit]

Advocates of spelling reform propose a variety of reforms which vary substantially in the depths of the changes they propose.

As noted above, a very light reform was in fact proposed by Noah Webster, some of whose proposals gave rise to the relatively trivial spelling differences between British and American English. His proposed reforms centered around ten general points:

- "-our" to "-or"

- "-re" to "-er"

- dropping final "k" in "publick," etc.

- changing "-ence" to "-ense" in "defence," etc.

- use single "l" in inflected forms, e.g. "traveled"

- use double "l" in words like "fulfill"

- use "-or" for "-er" where done so in Latin, e.g. "instructor," "visitor"

- drop final "e" where it has no effect on the preceding vowel, to give: ax, determin, definit, infinit, envelop, medicin, opposit, famin...

- use single "f" at end of words like "pontif," "plaintif"

- change "-ise" to "-ize" wherever this can be traced back to Latin and Greek (where a "z"/zeta *was* used in the spellings) or a more recent coining which uses the suffix "-ize" (from Greek "-izein")[15]

Webster's 3rd and 7th changes were accepted by most versions of English worldwide, and his 10th has made some headway in all varieties of English. All but the 8th and 9th proposals are accepted parts of American English, though a few individual examples such as "ax" are accepted alternate spellings. The two rejected proposals would have made a fairly significant impact on the appearance of written English. It will also be noted that there is nothing particularly American about the American spellings; they do not correspond in any way with North American pronunciations.[16] Though they arguably reduce the "Frenchness" of words like "center" or "color" just a tiny bit.

More drastic changes that would substantially alter the appearance of written English have met with consistent resistance. The movement for reformed spelling probably peaked in 1906. In that year, U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt issued an executive order requiring the Government Printing Office to use a list of simplified spellings prepared by the Simplified Spelling Board. The printing office complied, and printed Roosevelt's proclamation concerning the Panama Canal in the revised spellings. But when Congress reconvened in the Fall, they passed a resolution that "no money appropriated in this act shall be used (for) printing documents … unless same shall conform to the orthography … in … generally accepted dictionaries."[17][18]

Opposition and indifference[edit]

Webster's failures are as instructive as his successes. He made no large scale changes in how the system worked. Still, he failed to persuade the newly independent American republic to abandon the use of misleading silent E's because that change was too much to ask. Given this rejection, it seems unlikely that more radical reforms such as "Cut Spelling":[19]

“”Cut Spelng is a relativly new concept for modrnizing ritn english. It exploits th discovry that redundnt letrs cause lernrs th most trubl, and it therfor ataks that dificlty by removing those letrs. Typicl of th resultng spelings ar: det, iland, burglr, teachr, doctr, neibr, martr, acomodation, dautr, sycolojy. Few letrs ar actuly substituted, wich mens that the apearnce of text is chanjed far less than if evry sound wer respelt acordng to a fixd set of sound-symbl corespondnces. If u ar reading this, u wil hav been able to do so without much dificlty and without any practice or instruction at al.

|

or the "New Spelling" advocated by the English Spelling Society:[20]

“”It woz on the ferst dae ov the nue yeer that the anounsment woz maed, aulmoest simultaeneusli from three obzervatoris, that the moeshen ov the planet Neptune, the outermoest ov aul the planets that w(h)eel about the sun had bekum veri eratik.

|

— have much of a chance for acceptance. The spelling system, full as it is of irregularities, one-offs, and historical vestiges, may well seem an irresistible target for Rational Planners and Improvers. Fortunately, they're not getting anywhere. There are many reasons why.

Nobody wants this[edit]

Public resistance to spelling reform is consistently strong. This is not just a "Little Englander" thing: even modest spelling reforms in other countries have met with wide resistance, such as the 1996 German spelling reform which was widely ignored and eventually partly reversed.[21] The sheer difficulty of English spelling turns it into a prized skill, expressed in traditions like competitive spelling bees. Any significant change would devalue that acquired skill. Spelling reformers have appeared to protest a national spelling bee competition.[22]

English is too motley[edit]

English vocabulary is, as noted, a melding of Germanic, French, Latin and Greek words. Each of these layers has very different approaches to spelling. Reform proposals will inevitably tend to favor one approach over the other, resulting in a large percentage of words that must change spelling to fit the new scheme.

Not enough letters to go around[edit]

The great number of vowel sounds in English and the small number of vowel letters make phonemic spelling difficult to achieve. This is especially true for the three vowels /uː/ (e.g.: moon), /ʌ/ (e.g.: blood, sun) and /ʊ/ (e.g.: look, put) which are represented in English by only two symbols, oo and u. Spelling these phonemically cannot be done without resorting to odd letter combinations, diacritical marks, or new letters.[23] This will mean divergence from the internationally recognised base Latin alphabet and/or unintuive spelling and/or an increased difficulty of accommodating the alphabet into computer keyboards.

Sound changes and a rupture in underlying representation[edit]

Some inflections are pronounced differently in different words. For example, plural -s and possessive -'s are both pronounced differently in cat(')s /s/ and dog(')s /z/. The handling of this particular difficulty distinguishes morphemic proposals, which tend to spell such inflectional endings the same, from phonemic proposals that spell the endings precisely according to their pronunciation; the phonemic proposals hence have the major disadvantage of having to break up established underlying representation![]() , which is the way that we intuitively group certain sounds based on their grammatical function, the way they are actually pronounced, and other factors. [24]

, which is the way that we intuitively group certain sounds based on their grammatical function, the way they are actually pronounced, and other factors. [24]

Nobody has enough clout to make it stick[edit]

English is the only one of the top ten world languages that lacks a worldwide Academy or similar body with regulatory authority over the language, of a kind that can direct at least the usages of governments. Quite simply, no one has the authority to enact changes and make them stick.

Not that language regulatory bodies are all that effective, mind you. In all languages, use and common understanding are what dictate correctness. Those institutions don't regulate language—nobody really has the power to do so. A great example is the French nénuphar, which according to the Académie française![]() should be spelled nénufar; nobody does so. Another great example is the 1996 German spelling reform, which had all the effect of using a plastic spoon to propel a rowboat.

should be spelled nénufar; nobody does so. Another great example is the 1996 German spelling reform, which had all the effect of using a plastic spoon to propel a rowboat.

So, even if there were an English Academy of sorts, they still wouldn't be able to enact a radical spelling reform—they would just get widely mocked and ignored, à la Real Academia Española![]() .

.

Unfamiliarity[edit]

The spellings of some words – such as tongue and stomach – are so unindicative of their pronunciation that changing the spelling would noticeably change the shape of the word. Likewise, the irregular spelling of very common words such as are, done, do, and they makes it difficult to fix them without introducing a noticeable change to the appearance of English text. Let's face it: texts in phonetically respelled English look childish and illiterate. Phonetically respelled English is called "eye dialect![]() " and is used as a written convention to depict the speech of uneducated, lower-class characters.[25]

" and is used as a written convention to depict the speech of uneducated, lower-class characters.[25]

Sunk costs[edit]

Spelling reform may make pre-reform writings harder to understand and read in their original form, often necessitating transcription and republication. Today, few people choose to read old literature in the original spellings as most of it has been republished in modern spellings. Quite simply, the body of library books on the shelves and text on the Internet is a huge sunk cost, and a major reform of English spelling would cost a prodigious amount of money.[26]

Cognates in other languages[edit]

Technical English is understandable to a large number of people whose attainments in colloquial English are modest. The Latinate style of science and scholarship, however aesthetically annoying it is as prose, represents an attempt to write technical English using an international technical vocabulary that is fairly easily recognized among most speakers of all languages of European origin. Even a slight attempt to spell these words more in accord with the pronunciation would reveal the large gap between the English vowel system and the Romance systems, rendering these words far harder to recognize for non-native speakers. It would be far less likely that a speaker of a Romance language would recognize "psychology", "nation" or "geology" if they were spelt exactly as they are pronounced in English using modern orthography.

However, due to the relative systematicity of phonological transformations that have affected Latin-origin and Greek-origin borrowings, carefully planned phonetic spelling systems could largely circumvent this difficulty with features such as a palatalisation marker![]() and diacritics.

and diacritics.

International English varieties are too diverse[edit]

Spelling reform tends to make the assumption that English is consistently pronounced, when in fact there are a number of different pronunciations of the same words. The standard varieties of American, British, Irish, Canadian, Jamaican, New Zealand, South African and Australian English all have notable differences in phonology, and the US and UK in particular have a wide variety of dialects, not all of which are mutually intelligible.

English is also widespread in places such as India and Singapore in Asia, or Nigeria and Zimbabwe in Africa. Although it is often a second language in these countries for people of varying fluency, they also use English as an official language and have a significant number of native speakers. English is naturalised in India, and has a number of distinctive features and pronunciations there.

By producing a phonetic orthography for one particular variety, it is argued that the differences between these accents and dialects would be made far more obvious, and that global English would disintegrate further than it already has. Pushing through reform would likely result in two problematic situations: either one dialect would be used as the template for English spelling leaving everyone else stuck with English spelling of an accent they may not even be familiar with, or for every country or even region there would be notably different spelling customs.

There are many regional differences in pronunciation which make uniform spelling reform virtually impossible. In North America, the first letter of "herbs" is silent, whereas in most other forms of English it is pronounced. "Head" is pronounced "hed" in most areas, but as "heid" in most of Scotland. In the majority version of English, words like father, bother and law all have the same vowel, /ɑ/; in some outlying islands, these words are pronounced with a variety of sounds /a ɒ ɔ/ that are phonemic in those dialects. Additionally, choices would have to be made about whether the new spellings would reflect, say, rhotic or non-rhotic dialects (that is, those which pronounce all the "r"s and those which don't), and whether to accommodate dialects which do aberrant things like add "r" to the end of words whenever they feel like it![]() .

.

Also, consider the Chinese language, which consists of dialect continua,![]() some of which are mutually unintelligible in the spoken form. There is a great advantage to all Chinese speakers, as having a common written language that all literate people can understand is very convenient.[note 9]

some of which are mutually unintelligible in the spoken form. There is a great advantage to all Chinese speakers, as having a common written language that all literate people can understand is very convenient.[note 9]

No single phonetic orthography could handle this situation. The chaos of traditional spellings means that no one expects these dialect differences to make a difference in the spelling.[27][28] However, for morphemic orthographies (or even largely phonetic orthographies which nonetheless preserve most morphemes, such as the Russian orthography), dialectal differences are not generally a major issue.

English will continue to change[edit]

Almost all of the issues with English spelling revolve around the fact that English is constantly changing and no longer pronounced the way it used to be. Ongoing changes in the pronunciation of British English are being documented by phoneticians, such as the increased use of a /w/-type sound instead of /l/ (L-vocalization![]() ) or /r/ (R-labialization

) or /r/ (R-labialization![]() ) and a change from "t", "d", "s", "z" to "ch", "j", "sh", "ʒ" sounds in certain contexts, so that e.g. "Tuesday" becomes "Chooseday" (Yod-coalescence

) and a change from "t", "d", "s", "z" to "ch", "j", "sh", "ʒ" sounds in certain contexts, so that e.g. "Tuesday" becomes "Chooseday" (Yod-coalescence![]() ).[29][30] Future changes in the pronunciation of English are certain to happen.

).[29][30] Future changes in the pronunciation of English are certain to happen.

At this point, several things can happen. The language that has been respelled in accordance with the "alphabetic principle" can insist that the pronunciation encoded in the New Spelling is the correct one and that the current one is wrong. Or, it can hold fast to the alphabetic principle, and endure another round of planned obsolescence for everything that had already been transliterated into the Old New Spelling. Or, it can abandon the "alphabetic principle": keep the new spelling, use the new pronunciation, and add fresh irregularities to the New Spelling. The number of irregular New Spellings is guaranteed to increase over time.

None of these alternatives is desirable. However, a carefully planned orthographic system might prepare for likely future changes in pronunciation (such as yod-coalescence) and hence last longer before obsolescence, at which point slight updates might be introduced to adhere to the alphabetic principle. If implemented properly, such updates won't need to be rolled out more frequently than every couple of centuries. Still, the "alphabetic principle" is a dogmatic imposture that ignores the profound conservatism of written language and the way writing systems have historically worked.

The magnitude of systematic change[edit]

ðə ˈsɪmpləst θɪŋ tə du: wəd bi: tə ɹaɪt ˈɪŋɡlɪʃ ɪn ði: ˌɪntəɹˈnæʃənəl fəˈnɛtɪk ˈælfəˌbɛt. ði:z ˈsɪmbəlz ɔ:l həv fɪkst ˈmi:nɪŋz ðət ˈɛnibədi hu noʊz haʊ kən ɹi:d. ðəɹ ɪz ˈlɪtəl ˌæmbɪ ˈɡjuəti əˈbaʊt wʌt ði:z ˈkæɹɪktɜɹz mi:n. ðeɪ əɹ ɪn fækt beɪst ɑn ðə ˈlætɪn ˈælfəˌbɛt; ju: kən si: ˈmɛni fəˈmɪljəɹ fɹɛndz. ðɪs tɹænsˌlɪtəˈɹeɪʃən ɪz ˈpɹɪti bɹɔ:d. ðɪs ʤəst ʃoʊz ju: haʊ ˈθʌɹoʊ ðə ˈʧeɪnʤəz meɪd baɪ ə ˈtɹu:li fəˈnɛtɪk əɹˈθɑɡɹəfi wəd bi:.

- The simplest thing to do would be to write English in the International Phonetic Alphabet. These symbols all have fixed meanings that anybody who knows how can read. There is little ambiguity about what these characters mean. They are in fact based on the Latin alphabet; you can see many familiar friends. This transliteration is pretty broad. This just shows you how thorough the changes made by a truly phonetic orthography would be.

It isn't supposed to be phonetic[edit]

English spelling is therefore not phonetically based, because it isn't supposed to be, and making it phonetically based would cause more problems than it would solve. "English orthography is not a failed phonetic transcription system, invented out of madness or perversity. Instead, it is a more complex system that preserves bits of history (i.e. etymology), facilitates understanding, and also translates into sound." "English is one of the few major languages that has been blessed not to have had any large-scale formally sanctioned spelling reforms during its history, this despite the numerous attempts on the part of various individuals for the past three hundred years."[31][32]

Reforms within the system, making the rhymes more consistent, getting rid of sui generis spellings like restoring **tung for "tongue" (ME tunge) and **vittles for "victuals", and similar changes represent the limits of what's possible. It will not be possible to entirely dispel ambiguities or impose complete consistency. More purely phonemic reforms simply do not have any chance of acceptance. As "Johnson" at The Economist puts it, "English spelling, too, has its costs. The problem is that those costs are diffuse and baked into the system; they have a great deal of vested interest behind them. Anyone with the power to introduce a new system has already learned the old one; anyone it might benefit is probably under the age of five right now, or is foreign, and either way cannot vote. The costs of a reform would be both optional and sudden, and are too easily postponed until all the world's other ills are taken care of."[33]

“” For example, in Year 1 that useless letter "c" would be dropped to be replased either by "k" or "s," and likewise "x" would no longer be part of the alphabet. The only kase in which "c" would be retained would be the "ch" formation, which will be dealt with later. Year 2 might reform "w" spelling, so that "which" and "one" would take the same konsonant, wile Year 3 might well abolish "y" replasing it with "i" and Iear 4 might fiks the "g/j" anomali wonse and for all.

Jenerally, then, the improvement would kontinue iear bai iear with Iear 5 doing awai with useless double konsonants, and Iears 6-12 or so modifaiing vowlz and the rimeining voist and unvoist konsonants. Bai Iear 15 or sou, it wud fainali bi posibl tu meik ius ov thi ridandant letez "c," "y" and "x"--bai now jast a memori in the maindz ov ould doderez--tu riplais "ch," "sh," and "th" rispektivli. Fainali, xen, aafte sam 20 iers ov orxogrefkl riform, wi wud hev a lojikl, kohirnt speling in ius xrewawt xe Ingliy-spiking werld. |

| —M. J. Shields[34] |

The way forward[edit]

The weight of sheer inertia in traditional English spellings is substantial. The difficulty and ambiguity of the traditional system will continue to inspire calls for reform.

New media may suggest a way forward; playful variants such as 'leet' have had their brief moment of circulation. The brevity and tolerance of error encouraged by short message spaces and tiny keypads causes purists to wince at the abbreviations and simplifications often seen in text messages.[35][36]

There's no English Academy along the lines of the Académie Française that could be petitioned with proposals for change. Appeals directed at educational systems face a different challenge; at least in the United States, there are fifty separate educational bureaucracies that would need to be persuaded to implement a reform. If you do so, expect fifty different systems. The upside of this lack of regulation and authority is that there isn't going to be much official resistance if you choose to spell freely on your own time. Some may object that reforms achieved this way lack any kind of system or planning. But these sorts of changes have in fact succeeded in their goal of changing English spellings, at least in some places. None of the systematic plans for reform have ever achieved a significant following.

When you frame the task in front of you correctly, your goal becomes clearer, and in fact seems less difficult than securing acceptance for any heavy handed plan for top-down reform. What you need to do is quite simple. You need to make reformed, more phonetic spellings socially acceptable in the English-reading community.

If you believe that changing English spelling is a good idea, you should start by changing your own. During the 1930s, the Chicago Tribune adopted a set of simplified spellings. Many of the changes were scaled back, but several survived and became accepted usages in American English — analog, catalog, skilful, tranquility — while others like altho and thru became recognized colloquial variants. So long as what you write is outside the reach of bosses and pedagogues you may spell as you please. If you do so consistently, people will at least find it a quirk; but if they find your text unintelligible you'll know you've gone too far. Persuade bankable writers to not only support the movement, but to include new spellings in their work, and insist to their editors that their new spellings should be printed as written. Familiarity and exposure will translate into wider adoptions, and end with appearances of new spellings in edited prose and in dictionaries. So if you want to reform English spelling, just do it.[37]

Some proposals[edit]

- Christopher Upward's Cut Spelling.

- Harry Lindgren's SR1.

- George Bernard Shaw's Shavian alphabet.

Shaw is also associated with the string ghoti, supposed to represent "fish" ("gh" as in "cough", "o" as in "women", "ti" as in "nation"). In fact, Shaw "knew that people, 'being incorrigibly lazy, just laugh at spelling reformers as silly cranks'. So he attempted to reverse this prejudice and exhibit a phonetic alphabet as native good sense ... But when an enthusiastic convert suggested that 'ghoti' would be a reasonable way to spell 'fish' under the old system ..., the subject seemed about to be engulfed in the ridicule from which Shaw was determined to save it."[38]

Shaw is also associated with the string ghoti, supposed to represent "fish" ("gh" as in "cough", "o" as in "women", "ti" as in "nation"). In fact, Shaw "knew that people, 'being incorrigibly lazy, just laugh at spelling reformers as silly cranks'. So he attempted to reverse this prejudice and exhibit a phonetic alphabet as native good sense ... But when an enthusiastic convert suggested that 'ghoti' would be a reasonable way to spell 'fish' under the old system ..., the subject seemed about to be engulfed in the ridicule from which Shaw was determined to save it."[38] - Brigham Young's Deseret alphabet.

- The Nooalf Revolution bypasses the entire reform issue by offering the system as an English-based international spelling system.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- How Spelling Keeps Kids From Learning, The Atlantic

- The English Spelling Society

- Why English spelling needs modernising

- Simplified Spelling - from The American Language (1921) by H. L. Mencken

- The Futility of Spelling Reform - Mark Twain

- Spelling Reform – and the Real Reason It's Impossible – addresses common anti-reform arguments

- Hou tu pranownse Inglish – argues that English spelling isn't all that chaotic

- Why does Finnish give better PISA results? – suggests that the regularity of Finnish spelling and grammar is a factor contributing to Finland's top PISA performances, by indirectly benefiting science education as well

- Ghoti and the Ministry of Helth: Spelling Reform by Tom Scott on YouTube

- Handbook of Simplified Spelling, published by the Simplified Spelling Board wholly in simplified spelling

Notes[edit]

- ↑ The iffy ones are /x/ as in "loch", and /ʍ/ as in "which".

- ↑ In most of North America, there is no difference between the vowels of box, paw, and cart.[citation needed] British English usually distinguishes them. British English also introduces a new class of falling diphthongs because it usually drops /r/ from the closing rhyme of the syllable.

- ↑ What constitutes a separate phoneme that would merit a separate character in a purely phonetic alphabet varies from one language to another. English, for instance, does not distinguish the 'b' in "ball" from the 'b' in "brawl". But technically, the 'b' in "ball" is aspirated (/bʰ/) and the 'b' in "brawl" is not. In Hindi, this makes a difference, and the two sounds would be written with separate characters: 'bh' (भ) and 'b' (ब).

- ↑ See, for instance, The Chaos by Gerard Nolst Trenité:

Dearest creature in creation

Studying English pronunciation,

I will teach you in my verse

Sounds like corpse, corps, horse and worse.

I will keep you, Susy, busy,

Make your head with heat grow dizzy;

Tear in eye, your dress you'll tear;

Queer, fair seer, hear my prayer.

Pray, console your loving poet,

Make my coat look new, dear, sew it!

Just compare heart, hear and heard,

Dies and diet, lord and word.

Sword and sward, retain and Britain

(Mind the latter how it's written).

Made has not the sound of bade,

Say-said, pay-paid, laid but plaid.

Now I surely will not plague you

With such words as vague and ague,

But be careful how you speak,

Say: gush, bush, steak, streak, break, bleak....

- ↑ The group -ough is particularly random: through, though, thought, thorough, tough, trough.

- ↑ As an example, consider the unfamiliar word Yongle. Most native speakers, asked to say it, would probably come up with something like /jɑŋg.̩l/, after the example of native jungle or dongle. But run across the same string in context about the Yongle Emperor

in Chinese history, they will realize that the string is a foreign name that must be realized as /jɑŋ.lɛɪ/ or something similar.

in Chinese history, they will realize that the string is a foreign name that must be realized as /jɑŋ.lɛɪ/ or something similar.

- ↑ However, according to the BBC, the French-style pronunciation could be considered correct as the family name Pinochet itself was of French origin.

- ↑ The highest status variety of any language is called a standard language

or, in some contexts, an acrolect

or, in some contexts, an acrolect ; see also diglossia

; see also diglossia and code-switching

and code-switching .

.

- ↑ Although this is far from perfect; for example, written Cantonese does not accurately reflect Cantonese grammar, and the same is true for most varieties of Chinese, which use Mandarin grammar when written.

References[edit]

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on English phonology.

- ↑ Julia McGill, Onset and Rhyme

- ↑ Start the Campaign for Simple Spelling, New York Times, Apr. 1, 1906.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Great Vowel Shift.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Rogers, Henry. Writing systems: a linguistic approach. (Blackwell, 2005; ISBN 0-631-23463-2). Chapter, "English", p. 190 et. seq.

- ↑ Goswami, Usha (2005-09-06). "Chapter 28: Orthography, Phonology, and Reading Development: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective". in Malatesha, Joshi. Handbook of orthography and literacy. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc. pp. 463–464. ISBN 0-8058-4652-2.

- ↑ Paulesu, E, et al. "Dyslexia: Cultural Diversity and Biological Unity." Science 291.5511 (2001): 2165-2167.

- ↑ The Case For and Against Spelling Reform, The Spelling Society. (I sincerely doubt this. I think the key factor is whether a child likes and wants to read. For the child who reads edited prose, spelling is absorbed along the path and becomes second nature.)

- ↑ Economic and Social Costs of English Spelling, The Spelling Society.

- ↑ Aims and Objectives of the English Spelling Society. Actually, while there has never been a "systematic modernization" of English, the current system is not much older than 600 years, and spellings only became standardized in the 18th century.

- ↑ George B. Anderson, The Forgotten Crusader: Andrew Carnegie and the simplified spelling movement, The Spelling Society

- ↑ Tom de Castella, Could a new phonetic alphabet promote world peace?, BBC News Magazine, 19 February 2013

- ↑ Robert Craig and Antony Alexander, Chapter Eighteen: A History of English Spelling Revision, in Lango: "Language Organization", 1996

- ↑ A Step Toward World-Wide Peace, Saturday Evening Post, Jan. 28, 1904

- ↑ Kenneth Ives, Written Dialects (1979)

- ↑ And they add ambiguities; "envelop" is a verb that does not rhyme with envelope.

- ↑ Thomas V. DiBacco, "Teddy Roosevelt, Rough Rider Over Spelling Rules", The Wall Street Journal, Apr. 16, 2015.

- ↑ Cornell Kimball, History of Spelling Reform.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Cut Spelling.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on English Spelling Society.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on German orthography reform of 1996.

- ↑ Enuf is Enuf — The Skeptical Eye

- ↑ Lindgren, Harry (1969). Spelling Reform: A New Approach. Sydney: Alpha Books. p. 59.

- ↑ https://www.linguisticsnetwork.com/levels-of-representation/

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on eye dialect.

- ↑ G. L. Wy can't we get it rite? — The Economist, Sep 15th 2010

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Rhotic and non-rhotic accents.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Linking and intrusive R.

- ↑ Our Changing Pronunciation, J C Wells, University College London: Summary of a talk given at the British Association annual Festival of Science, Cardiff, 9 September 1998

- ↑ Phonological Change, Learning: Sounds Familiar, British Library

- ↑ R. L. Venezky, The American Way of Spelling, (Guilford, 1999), p. 4

- ↑ R. Sproat, A computational theory of writing systems (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 192

- ↑ Spelling reform: It didn't go so well in Germany, The Economist, Sept. 15, 2010

- ↑ A Plan for the Improvement of English Spelling Usually misattributed to Mark Twain, but actually written in a letter to The Economist by M. J. Shields in 1971.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Leet.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on SMS language.

- ↑ The Chicago Tribune, The Spelling Society

- ↑ Michael Holroyd, in Bernard Shaw: Volume III: 1918-1950: The Lure of Fantasy (Chatto & Windus, 1991), p. 501

KSF

KSF